Abstract

Background

We assessed feasibility and safety of laparoscopic sigmoidectomy for complicated fistulizing diverticular disease in a tertiary care colorectal center.

Methods

A single-center retrospective study of patients undergoing sigmoidectomy for fistulizing diverticular disease between 2011 and 2021 was realized. Primary outcomes were rates of conversion to open surgery and severe postoperative morbidity at 30 days. Secondary outcomes included rates of postoperative bladder leaks on cystogram.

Results

Among the 104 patients, 32.7% had previous laparotomy. Laparoscopy was the initial approach in 103 (99.0%), with 6 (5.8%) conversions to laparotomy. Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ III complication rate at 30 days was 10.6%, including two (1.9%) anastomotic leaks. The median postoperative length of stay was 4.0 days. Seven (6.7%) patients underwent reoperation, six (5.8%) were readmitted, and one (0.9%) died within 30 days. Twelve (11.5%) ileostomies were created initially, and two (1.9%) were created following anastomotic leaks. At last follow-up, 101 (97.1%) patients were stoma-free. Urgent surgeries had a higher rate of severe postoperative complications. Among colovesical fistula patients (n = 73), postoperative cystograms were performed in 56.2%, identifying two out of the three bladder leaks detected on closed suction drains. No differences in postoperative outcomes occurred between groups with and without postoperative cystograms, including Foley catheter removal within seven days (73.2% vs. 90.6%, p = 0.08).

Conclusions

Laparoscopic surgery for complicated fistulizing diverticulitis showed low rates of severe complications, conversions to open surgery and permanent stomas in high-volume colorectal center.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Laparoscopic elective sigmoidectomy has become the standard of care for diverticular disease resection. It has demonstrated several benefits over open surgery, such as a shorter length of stay (LOS), reduced need for pain medication and cost-effectiveness [1, 2]. Fistulizing diverticular disease, which can develop in up to 20% of patients [3], once was a contraindication for minimally invasive surgery (MIS) until recent small retrospective series demonstrated its safety [4]. Nonetheless, it represents a more complex surgical challenge than standard sigmoidectomy. Hence, laparoscopic surgery is less frequently used in this context, and is associated with high conversion rates to open surgery, ranging from 22 to 42% [5,6,7,8,9].

We reviewed the experience from the past 10 years for fistulizing diverticular disease treatment at a high-volume tertiary care colorectal unit. Our objective was to assess the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic surgery for fistulizing diverticular disease. We hypothesized that conversion rate to open surgery would be markedly lower than reported in the literature, and that postoperative morbidity would also be low.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This was a single-institutional retrospective observational study of all consecutive patients who underwent sigmoidectomy for fistulizing diverticular disease between January 2011 and December 2021 at Hôpital Saint-François d’Assise, Québec, Canada. The study protocol was approved by the institution’s ethics committee.

Participants

Patients who underwent either open or minimally invasive colonic resection for left or sigmoid colonic fistula resulting from diverticular disease were included. Urgent or emergent surgeries were also included. Urgent surgery was defined as patients undergoing surgery during the same hospitalization as their diverticulitis episode due to refractory symptoms, while emergent surgery was defined as unstable patients requiring prompt surgical intervention. In contrast, patients undergoing elective surgery were treated medically for their diverticulitis episode, and an elective colonic resection was planned subsequently following discharge. Fistulas arising from other etiologies, such as inflammatory bowel disease, neoplasia, or iatrogenic following surgery were excluded. All patients underwent a diagnostic computed tomography scan prior to surgery, occasionally with added colonoscopy, cystoscopy, or hydrosoluble enema. Follow-ups were performed between eight and ten weeks postoperatively.

Data collection

Standardized chart review was performed by two of the investigators (R.B., AJ. S.). Data regarding demographics, fistula types, surgical indications, procedure details and postoperative results were collected retrospectively. For patients with colovesical fistulas, data on postoperative cystograms usage and timing of Foley catheter removal were collected. Postoperative complications were reported using the Clavien-Dindo classification system [10] in which grade III or higher were considered as severe.

Operative technique

All sigmoidectomies were performed using a similar technique by eight colorectal surgeons. No bowel preparation was given other than two sodium phosphate Fleet® enemas prior to the surgery. Laparoscopic approach included four to six ports, splenic flexure mobilization, inferior mesenteric artery ligation, upper rectal transection, left lower quadrant extraction incision, circular stapler anastomosis, and anastomotic air leak test. All surgeons performed resections according to oncologic planes of dissections. Diverting loop ileostomy, omental flap interposition on the colorectal anastomosis and closed suction drains use were performed according to the surgeon’s perioperative judgment and preference.

Fistula management, including decision to perform intraoperative bladder instillation of methylene blue, bladder repair, and postoperative cystogram, varied according to cases and surgeon preferences. However, all patients with bladder repairs underwent postoperative cystograms. Urologists were not involved unless ureteral involvement or trauma were encountered. Repair of colovaginal fistula with laparoscopic sutures was performed if the vaginal deficit was noticeable only. Coloenteric fistulas were addressed with segmental intestinal resection and stapled anastomosis.

Study outcomes

Primary outcomes were rates of conversion to open surgery and of severe postoperative morbidity at 30 days. Secondary outcomes included the rate of postoperative bladder leaks on cystogram, hospital LOS, stoma-free rate, as well as readmission, reoperation, and mortality rates at 30 days. Comparisons were performed between patients with Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ III complications and the remaining cohort to assess risk factors for severe postoperative complications, and between patients undergoing urgent and elective surgeries. Patients with colovesical fistula were compared based on the use of postoperative cystogram. Early Foley catheter removal was defined as withdrawal within 7 days, while late removal referred to withdrawal after than 7 days.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were reported using proportions and percentages while medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) were used for continuous variables. Exact Pearson Chi Square Test and Wilcoxon Mann Whitney Test were used for comparisons between groups. Statistical tests were two-sided and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was realized with SAS Statistical Software v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Participants

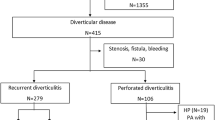

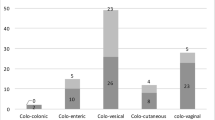

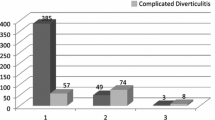

Between January 2011 and December 2021, 675 colonic resections for left-sided diverticulitis were performed at our center. Among them, 104 consecutive patients underwent sigmoidectomy for fistulizing diverticular disease and were included in the study. Median age was 64 years and median BMI was 27 kg/m2. Most patients had an ASA class of II (74.0%). Half of the cohort had previous abdominal surgeries including 34 (32.7%) laparotomies. The most frequent fistula type was colovesical (57.7%) followed by colovaginal (19.2%). Multiple concomitant fistulas were reported in 13.5% of patients. Most patients had surgery in an elective setting (86.5%) while 14 (13.5%) underwent urgent surgery. In the urgent surgery group, seven patients had an abscess unresponsive to antibiotics and/or drainage, four had a clinic of occlusive symptoms, and three had persistent inflammation and abdominal pain despite prolonged antibiotic treatment. No patients had emergency surgery as none of them were unstable or presented diffuse peritonitis.The median follow-up was of 10.9 (6.2–25.7) weeks. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Intraoperative characteristics

During the whole study period, laparoscopy was chosen as the initial approach in all patients except one (99.0%) with an extensive concomitant Rives-Stoppa incisional hernia repair. There was no hand-assisted surgery. All patients underwent end-to-end primary anastomosis using a circular stapler. Diverting loop ileostomy was created in 11.5% of patients at primary surgery. According to surgeon preference, omental flap insertion between the anastomosis and the bladder and ureteral stenting were used in 47.1% and 6.7% of cases, respectively. A urologist was involved intraoperatively in one case only (ureteral laceration).

In the subgroup with colovesical fistulas (n = 73), bladder instillation with methylene blue was performed in 22 (30.1%), and extravasation was observed in four (18.2%). Direct visualization of the bladder deficit was observed in 14 patients (including those with methylene blue extravasation) and cystorrhaphy was realized in ten of them. Among the four patients left without cystorrhaphy, two had omental patches with drains and two with small deficits had no intervention. All other colovesical fistulas underwent sigmoidectomy solely, with or without omental flap. Intraoperative management of colovesical fistulas is reported in Fig. 1.

Intraoperative complications occurred in 7.7% of patients. Six (5.8%) necessitated conversion to open surgery, five of them due to adhesions and one due to a major bleed. The median operative time was 193 min and the estimated blood loss was 100 ml. Intraoperative results are presented in Table 2.

Postoperative complications and outcomes

The median hospital LOS was 4.0 days. All elective surgeries were managed according to Enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. Overall postoperative morbidity rate was 27.9%, most commonly postoperative ileus (14.4%). Three (2.9%) asymptomatic bladder leaks occurred. Eleven (10.6%) patients experienced grade ≥ III Clavien-Dindo complications at 30 days, consisting of two (1.9%) anastomotic leaks, one (0.9%) cardiac event, two (1.9%) bowel obstructions at the stoma site, two (1.9%) asymptomatic bladder leaks requiring cystoscopy, one (0.9%) anastomotic bleeding, one (0.9%) unrecognized enterotomy, one (0.9%) inverted maturation of ileostomy and two (1.9%) bleeding or hematomas. Of these complications, reoperation was needed in seven (6.7%) patients, including two loop ileostomies for anastomotic leaks. Complications are detailed in Table 3. Six (5.8%) patients were readmitted following discharge (Clostridium Difficile colitis, high ileostomy output [2], reoperation of inverted ileostomy maturation, enterocutaneous fistula and pyelonephritis). No fistula recurrence was reported. Among the 12 patients with initial loop ileostomy and the two with ileostomy secondary to anastomotic leaks, 11 underwent stoma closure while one was lost at follow-up. Hence, 97.1% of the cohort (101/104) was stoma-free at the last follow-up. One (0.9%) patient with preoperative severe cardiac failure decided to receive palliative care following her diverting ileostomy for an anastomotic leak. She died within 30 days from cardiac failure.

Comparisons between patients with severe complications (n = 11) and the remaining cohort (n = 93) revealed older age (76 vs. 64, p = 0.03), higher rates of urgent surgeries (40.0% vs. 10.6%, p = 0.03) and of multiple concomitant fistulas (50.0 vs. 9.6%, p = 0.02), longer operative time (240 vs. 192 min, p = 0.04) and higher blood loss (300 vs. 75 ml, p = 0.01).

When comparing patients undergoing urgent sigmoidectomies (n = 14, 13.5%) with elective sigmoidectomies (n = 90, 86.5%), Clavien-Dindo ≥ grade III complications were more frequent in the former (28.6% vs. 6.7%, p = 0.03), as were diverting ileostomies at primary surgery (35.6% vs. 7.8%, p = 0.01). All other differences, including conversion rate (14.3% vs. 4.4%, p = 0.18), were not statistically significant.

Cystogram and urinary catheter management

Among the 73 patients with colovesical fistulas, all kept their Foley catheter postoperatively, with a median of seven days before removal. The majority (80.8%) had it removed within seven days. Postoperative cystograms before Foley removal were performed based on surgeon preference in 41 (56.2%). Three patients had a postoperative asymptomatic bladder leak. All were detected with creatinine dosage on closed suction drain following elevated output between postoperative days 1 and 3. These three patients all had an intraoperative methylene blue instillation test (one positive) and no bladder repair. Two of the leaks were visualized on postoperative cystograms (2/41, 4.9%), while the third one was not assessed with an early postoperative cystogram. All bladder leaks resolved with prolonged Foley indwelling time, with removal following either a negative cystogram or cystoscopy between postoperative days 13 and 70.

When comparing those with (n = 41) and those without (n = 32) postoperative cystogram, the only statistically significant difference was the higher rate of intraoperative cystorrhaphy in the cystogram group (22.0% vs. 3.1%, p = 0.04). Fewer patients had their Foley catheter removed within seven days in the cystogram group; however, this was not statistically significant (73.2% vs. 90.6%, p = 0.08). No statistical difference in any other outcomes were observed, including the hospital LOS (5.0 vs. 3.5 days, p = 0.2).

Discussion

In this retrospective study exploring the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic sigmoidectomy for fistulizing diverticular disease, we reported low rates of conversion and serious complications. Only one patient underwent an upfront laparotomy during the whole study period although a third of the cohort had prior open abdominal surgeries. All patients underwent primary anastomosis with low anastomotic leak rate and almost all patients ended up stoma-free. This study represents one of the largest series of laparoscopic sigmoid resections for complex fistulizing diverticular disease.

Martinolich et al. (2019) reported 106 cases of patients treated with MIS sigmoidectomies for fistulizing diverticular disease, after excluding upfront open surgeries [5]. The conversion rate, complication rate, and LOS were of 34.9%, 26.4% and 6.6 days, respectively. Other series reported conversion rates between 22% and 42% in small selected cohorts [5,6,7,8,9]. A meta-analysis by Cirocchi et al. (2015) included all studies with laparoscopic sigmoidectomy for fistulizing diverticular disease and reported a conversion rate of 19.7% among 250 patients [11]. The small sample size and heterogeneity prevented any firm conclusions on the laparoscopic approach. In the present study, the rate of conversion is remarkably lower than those reported previously. Contrary to other studies, urgent sigmoidectomies were included and the conversion rate of this group alone was still low, reinforcing the fact that laparoscopy should be attempted in this setting. This unique low conversion rate might be explained by the volume and expertise of the surgeons at our center and may not apply to any different setup. In situations where a surgeon judges that the laparoscopic approach presents as challenging, reference in a specialized colorectal center should be considered.

Severe complications occurred more frequently in older age patients, concomitant fistulas and urgent setting. These patients had a longer operative time and higher blood loss, suggesting more technically challenging disease. Patients with urgent surgeries greatly contributed to increase the severe complication rate. These characteristics could help identify patients at greater risk of postoperative complications. However, even these patients would likely benefit from MIS attempt as upfront laparotomy or conversion to open surgery results in similar or less favorable outcomes in this set up [5, 6, 12, 13].

There are no clear recommendations on bladder management following colovesical fistula surgeries. Recent studies favored early removal of Foley catheter within seven days, as it was not associated with an increase in complications [14]. Moreover, urinary tract infections, bladder atony and longer hospitalization were associated with a longer indwelling time [15]. The role of postoperative cystogram is also poorly defined. Although commonly used, it might not be useful, especially in cases of simple bladder fistula, unidentified bladder defect, or negative perioperative bladder leak test [14,15,16]. It has a low diagnostic yield of 3% and could add cost when used routinely, while dosage of drain creatinine was found to have good predictive positive and negative values [15, 16]. Moreover, the optimal intraoperative bladder management is also unknown. While some studies favor bladder repair [14], others suggest it only when the deficit is visible, resulting in most colovesical fistulas not requiring repair [16,17,18]. In our colovesical fistula subgroup, the majority had their Foley catheter removed within 7 days. Most patients did not have bladder repair, which was reserved for identified deficit. Postoperative cystogram was performed in 56.2% and demonstrated two bladder leaks in patients for which diagnosis was already made by creatinine dosage on drains. In the cystogram group, LOS appeared to be longer and fewer patients had an early Foley removal; however, these differences were not statistically significant. In conjunction with prior studies, systematic postoperative cystogram was questionable due to rare leak detection.

Compared to previous studies evaluating MIS in highly selected subjects, this present study included all patients with a sigmoidectomy for fistulizing diverticular disease, without any other selection criteria. There was no exclusion of urgent surgeries as we believe that these patients should also benefit from MIS. Moreover, the surgeries were performed by a small group of surgeons ensuring a more homogeneous approach. This study also has several limitations. The retrospective design limits the certainty of our finding and implies heterogenous data. The specific management of fistulas, such as methylene blue instillation, cystograms or fistula repairs were based on surgeon preferences and were not protocolized. There was no possible comparison group as only one patient underwent upfront open surgery and as the conversion rate was very low. The follow-up of almost 11 weeks may appear as short. However, this is the standard follow-up in our center for benign colonic resection in patients with favorable evolution, and it should allow for the detection of most relevant postoperative complications. When comparing patients with and without postoperative cystogram, the small sample size of the colovesical fistula subgroup could result in a lack of statistical significance (type II error). Randomized controlled trials should be conducted to enlighten the best postoperative management for colovesical fistula as there are no evidenced-based recommendation. Finally, as the study was conducted in a tertiary care colorectal center with expertise in MIS, these results might not be reproducible in all centers, therefore limiting the external validity of the study.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic surgery for complicated fistulizing diverticular disease appears to be associated with low rates of severe postoperative morbidity, conversion to open surgery and permanent stoma in high-volume colorectal centers. Consideration should be given to referral of these difficult cases in high-volume centers to offer MIS benefit to these patients.

Data availability

All data will be available on demand.

Change history

30 July 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-024-03425-6

References

Bhakta A, Tafen M, Glotzer O et al (2016) Laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy for complicated diverticulitis is safe: review of 576 consecutive colectomies. Surg Endosc 30(4):1629–1634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4393-5

Senagore AJ, Duepree HJ, Delaney CP et al (2002) Cost structure of laparoscopic and open sigmoid colectomy for diverticular disease: similarities and differences. Dis Colon Rectum 45(4):485–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-004-6225-x

Menenakos E, Hahnloser D, Nassiopoulos K et al (2003) Laparoscopic surgery for fistulas that complicate diverticular disease. Langenbecks Arch Surg 388(3):189–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-003-0392-4

Abbass MA, Tsay AT, Abbas MA (2013) Laparoscopic resection of chronic sigmoid diverticulitis with fistula. Jsls;17(4):636 40.10.4293/108680813x13693422520512

Martinolich J, Croasdale DR, Bhakta AS et al (2019) Laparoscopic Surgery for Diverticular Fistulas: Outcomes of 111 Consecutive Cases at a Single Institution. J Gastrointest Surg; 23(5):1015 – 21.10.1007/s11605-018-3950-3

DeLeon MF, Sapci I, Akeel NY et al (2019) Diverticular Colovaginal Fistulas: What Factors Contribute to Successful Surgical Management? Dis Colon Rectum; 62(9):1079 – 84.10.1097/dcr.0000000000001445

Wen Y, Althans AR, Brady JT et al (2017) Evaluating surgical management and outcomes of colovaginal fistulas. Am J Surg;213(3):5537.10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.11.006

Bartus CM, Lipof T, Sarwar CM et al (2005) Colovesical fistula: not a contraindication to elective laparoscopic colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum; 48(2):233 – 6.10.1007/s10350-004-0849-8

Pokala N, Delaney CP, Brady KM et al (2005) Elective laparoscopic surgery for benign internal enteric fistulas: a review of 43 cases. Surg Endosc 19(2):222–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-004-8801-5

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg; 240(2):205 – 13.10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae

Cirocchi R, Arezzo A, Renzi C et al (2015) Is laparoscopic surgery the best treatment in fistulas complicating diverticular disease of the sigmoid colon? A systematic review. Int J Surg 24Pt A:95–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.11.007

Badic B, Leroux G, Thereaux J et al (2017) Colovesical Fistula complicating Diverticular Disease: a 14-Year experience. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 27(2):94–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/sle.0000000000000375

de la Fuente Hernández N, Martínez Sánchez C, Solans Solerdelcoll M et al (2020) Colovesical Fistula: Applicability of the Laparoscopic Approach and results according to etiology. Cir Esp (Engl Ed) 98(6):336–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2019.11.011

de Moya MA, Zacharias N, Osbourne A et al (2009) Colovesical fistula repair: is early Foley catheter removal safe? J Surg Res; 156(2):274 – 7.10.1016/j.jss.2009.03.094

Dolejs SC, Penning AJ, Guzman MJ et al (2019) Perioperative Management of Patients with Colovesical Fistula. J Gastrointest Surg; 23(9):1867 – 73.10.1007/s11605-018-4034-0

Bertelson NL, Abcarian H, Kalkbrenner KA et al (2018) Diverticular colovesical fistula: What should we really be doing? Tech Coloproctol; 22(1):31 – 6.10.1007/s10151-017-1733-6

Ferguson GG, Lee EW, Hunt SR et al (2008) Management of the bladder during surgical treatment of enterovesical fistulas from benign bowel disease. J Am Coll Surg 207(4):569–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.05.006

Engledow AH, Pakzad F, Ward NJ et al (2007) Laparoscopic resection of diverticular fistulae: a 10-year experience. Colorectal Dis 9(7):632–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01268.x

Funding

No source of funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.B.: Conception and design, data acquisition and analysis, data interpretation, drafting of manuscript, critical revision of manuscript, final approval of manuscriptAJ.S: Conception and design, data interpretation, critical revision of manuscript, final approval of manuscriptF. RF., F.L., P.B. and S.D. : Conception and design, data interpretation, critical revision of manuscript, final approval of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Study protocol was reviewed by the ethics committee of CHU de Québec-Université Laval. Ethical approval was waived in view of the retrospective nature of the study and all the procedures being performed were part of the routine care.

Institution at which the work was performed

CHU de Québec - Université Laval, pavillon Saint-François d’Assise, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada.

Data presentation

The result of this work was presented at SAGES 2023 annual meeting in Montreal.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Raphaëlle Brière, Anne-Julie Simard, François Rouleau-Fournier, François Letarte, Philippe Bouchard and Sébastien Drolet have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article unfortunately contained mistakes introduced during the production process. All the results of Tables 2 and 3, and some results of the Table 1 were not at the right place. The original article has been corrected.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Brière, R., Simard, AJ., Rouleau-Fournier, F. et al. Retrospective study on the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic surgery for complicated fistulizing diverticular disease in a high-volume colorectal center. Langenbecks Arch Surg 409, 208 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-024-03396-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-024-03396-8