Abstract

Purpose

This study evaluated the prognostic value of C-reactive protein–to–albumin (CAR) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios (NLR) in conjunction with host-related factors in patients with unresectable advanced or recurrent gastric cancer.

Methods

A total of 411 patients with unresectable advanced gastric cancer were treated at Kochi Medical School between 2007 and 2019. Associations between clinicopathological parameters and systemic inflammatory and nutritional markers, including CAR and NLR, with overall survival were analyzed retrospectively.

Results

The optimal cut-off values of predicted median survival time were 0.096 (sensitivity, 74.9%; specificity, 42.5%) for CAR and 3.47 (sensitivity, 64.1%; specificity, 57.5%) for NLR, based on the results of receiver operating characteristic analysis. A weak significant positive correlation was identified between CAR and NLR (r = 0.388, P < 0.001). The median survival time was significantly higher in patients with intestinal-type than those with diffuse-type histology (18.3 months vs. 9.5 months; P = 0.001), CAR < 0.096 than those with CAR ≥ 0.096 (14.8 months vs. 9.9 months; P < 0.029), and those with NLR < 3.47 than NLR ≥ 3.47 (14.7 months vs. 8.8 months; P < 0.001). Multivariate survival analysis revealed that diffuse-type histology (hazard ratio (HR) 1.865; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.397–2.490; P < 0.001)), 1 or more performance status (HR 11.510; 95% CI 7.941–16.683; P < 0.001), and NLR ≥ 3.47 (HR 1.341; 95% CI 1.174–1.769; P = 0.023) were significantly associated with independent predictors of worse prognosis.

Conclusions

High CAR and NLR are associated with poor survival in patients with unresectable and recurrent gastric cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fourth most prevalent malignancy worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths [1,2,3]. Despite the continuous advancements in therapeutic methods, studies have shown that patients with unresectable advanced or metastatic gastric cancer have a poor prognosis [4]. Chemotherapy with or without molecular targeted drugs is the recommended treatment for these patients, while extensive surgery with regional lymphadenectomy is an effective treatment for localized disease [5]. Various prognostic factors used to predict the long-term survival of patients with gastric cancer have been reported, with carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19-9) as the most commonly used tumor biomarkers [6]. However, the sensitivity and specificity of these tumor markers are insufficient in clinical practice.

Recently, significant attention has been paid to the association between malignancies and various nutritional status and inflammatory biomarkers, which have been considered crucial for predicting cancer survival [7, 8]. Several studies have suggested that preoperative systemic inflammatory and nutritional markers such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), prognostic nutrition index (PNI), and Glasgow prognostic score (GPS) are associated with the progression and prognosis of many malignancies [9]. Recent studies have also indicated that an elevated C-reactive protein–to–albumin ratio (CAR) was independently associated with poor outcomes in patients with gastric cancer, including cohorts with different stages [10, 11]. However, the predictive ability of CAR in patients with unresectable advanced gastric cancer remains insufficient when used individually, and novel biomarkers that could predict prognosis precisely should be explored.

Recent advances of new chemotherapeutic and molecular targeting agents improved the survival of patients with metastatic gastric cancer. In addition, conversion therapy, which is a surgical treatment aiming at a curative resection after drug therapy for tumors that were originally unresectable, has become a popular concept in the field of surgical oncology [12, 13]. At the same time, the treatment for recurrent cancer patients after curative resection by surgery is also important. Therefore, the exploration of potential prognostic markers in patients with unresectable advanced or recurrent gastric cancer is a prominent issue in the surgical field.

Therefore, we investigated the prognostic value of systemic inflammatory and nutritional indices on survival, including CAR and NLR in conjunction with host-related factors, calculated at the time of diagnosis in a large sample of patients with unresectable advanced or recurrent gastric cancer based on pathological parameters.

Patients and methods

Patients

This retrospective study included 411 patients with unresectable advanced or recurrent gastric cancer at Kochi Medical School between January 2007 and December 2019 based on a medical information database. Gastric cancer diagnoses were determined by esophagogastroduodenoscopy, biopsy specimen analysis, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasonography of the abdomen, and positron emission tomography. We reviewed the medical records and collected data on the following patient characteristics: age, sex, histological type, history of gastrectomy, metastatic sites, baseline blood cell count, and serum chemical parameters before treatment initiation. Patients who might be indicated for surgery including the case of isolated local recurrence were excluded in this study.

Blood samples were collected and analyzed for serum concentrations of albumin and C-reactive protein (CRP), as well as neutrophil and lymphocyte cell counts. Tumor histology was categorized as intestinal type (well-differentiated, moderately differentiated, and papillary adenocarcinoma) or diffuse type (poorly differentiated, mucinous adenocarcinoma and signet ring cell carcinoma) according to Lauren’s classification [14].

Treatment

When the patients had insufficient organ function or performance status according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 3 or more, best supportive care (BSC) to palliate symptoms was performed. Patients who could not eat enough due to refractory cancer cachexia or uncontrollable stenosis of the gastrointestinal tract also received BSC. Patients with both a human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status of 3 + or 2 + (based on immunohistochemical staining of tumor samples) and positive results by fluorescence in situ hybridization analyses following their clinical examination were treated with the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab to the combination of cisplatin and capecitabine, according to the ToGA trial, which demonstrated that response rate, progression-free survival, and overall survival are greatly improved by adding trastuzumab [15].

The patients with sufficient organ function and performance status according to the ECOG PS of 2 or less were treated using platinum compounds plus fluoropyrimidines as first-line treatment, following the previous large-scale randomized controlled trials [16, 17]. A total of 214 patients (67.7%) were shifted to second-line treatment with taxanes, irinotecan, and ramucirumab after evidence of disease progression [18]. Furthermore, 171 patients (54.1%) were shifted to third-line treatment using other anti-tumor drugs, including nivolumab and trifluridine tipiracil, similar to recent randomized controlled trials [19, 20].

Overall survival (OS) after treatment was calculated from the date of pathological diagnosis to the date of death or the final follow-up visit.

Measurement of serum variables

Venous blood samples were collected at the time of diagnosis and during chemotherapy, and the proportion of particular cell types was determined using Giemsa-stained blood smears. Cut-off values for the target laboratory examinations were defined by the upper limit of normal values set by the automatic biochemical detector, the machine used in our hospital for biochemical analysis. The recommended normal upper limits of serum tumor markers were as follows: 3.4 ng/mL for CEA, 37 ng/mL for CA19–9, and 35 U/mL for CA125. A result was considered positive when the value of the serum marker was higher than the upper limit for this marker in serum from healthy patients. The neutrophil count divided by the lymphocyte count and the CRP divided by albumin were recorded as NLR and CAR, respectively. The PNI was calculated using the following formula: PNI = serum albumin level (g/L) + [5 × total lymphocyte count (/L)] [21].

Statistical analysis

Differences between mean values of the two patient groups were tested for significance using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables. The correlation between each variable was evaluated by calculating Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficient. The optimal cut-off level was determined based on receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis using Youden’s index. We used the Kaplan–Meier method to generate cumulative survival rates and compared them using the log-rank test to evaluate the statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0. The Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to identify factors independently associated with survival. For the subgroup analysis of OS, the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) within each subgroup were summarized. When various factors were considered in the multivariate analysis, all were dichotomized according to the univariate analysis.

Results

Patient characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of patients with unresectable advanced gastric cancer. The study cohort comprised 265 men and 146 women with a median age of 70 years (range, 19–93 years). The median survival time was 11.6 months (range, 0.7–85.5 months), and the overall 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival rates after therapy were 49.2%, 24.7%, and 14.4%, respectively. Of these 411 patients, 157 had intestinal-type tumors and 254 had diffuse-type tumors. On diagnosis, 293 patients were classified as having metastatic cancer and 118 were classified as having recurrent cancer following curative resection of gastric cancer. The median pretreatment values of CEA, CA19–9, and CA125 among all 411 patients were 4.9 ng/mL (range, 0.3–7882 ng/mL), 21.8 U/mL (range, 0.6–10,779 U/mL), and 22.8 U/mL (range, 3.7–12,638 U/mL), respectively. The median, pretreatment CAR, NLR, and PNI across all patients (n = 411) were 0.253 (range, 0.0–9.588), 3.51 (range, 0.24–31.33), and 36.0 (range, 0.0–50.1), respectively.

Correlation of serum variables and survival

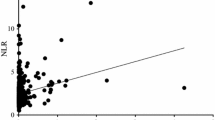

The correlation between each variable such as serum inflammatory and nutritional index, and survival was evaluated. A weak significant positive correlation was identified between CAR and NLR (r = 0.388, P < 0.001; Fig. 1). There was no significant relationship between OS and CAR (r = − 0.102, P = 0.039), OS and NLR (r = − 0.167, P < 0.001), and OS and PNI (r = 0.173, P < 0.001).

Cut-off values of CAR and NLR

According to ROC curve analysis for the predicted median survival time, the optimal cut-off values of CAR, NLR, and PNI for OS were 0.096 (sensitivity, 74.9%; specificity, 42.5%), 3.47 (sensitivity, 64.1%; specificity, 57.5%), and 30.1 (sensitivity, 74.3%; specificity, 27.4%), respectively (Fig. 2). The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.573 (95% CI, 0.513–0.634; P = 0.019) for CAR, 0.599 (95% CI, 0.539–0.659; P = 0.002) for NLR, and 0.444 (95% CI, 0.384–0.505; P = 0.074) for PNI. When the combined value that was calculated by multiplying CAR by ten and adding NLR to increase diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, the optimal cut-off values of this marker for OS were 5.02 (sensitivity, 71.9%; specificity, 49.7%).

Association of serum inflammatory and nutritional index and survival

The median survival time for patients treated with anti-tumor drug was significantly higher than for those without anti-tumor drug (14.2 months vs. 3.5 months; P < 0.001) (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the median survival time of patients with intestinal-type histology was significantly higher than of those with diffuse-type histology (18.3 months vs. 9.5 months; P = 0.001) (Fig. 3B). The patients (n = 411) were divided into group based on the pretreatment median CAR (< 0.096 and ≥ 0.096), NLR (< 3.47 and ≥ 3.47), and PNI (< 30.1 and ≥ 30.1). The median survival time was also significantly higher in patients with CAR < 0.096 than those with CAR ≥ 0.096 (14.8 months vs. 9.9 months; P < 0.029) and NLR < 3.47 than those with NLR ≥ 3.47 (14.7 months vs. 8.8 months; P < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival of patients with unresectable and recurrent gastric cancer according to C-reactive protein–to–albumin ratio (A) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (B). There were significant differences in survival between the groups (P = 0.030, P < 0.001, respectively; stratified log-rank test)

Univariate and multivariate survival analyses

Table 2 summarizes the clinical characteristics and survival of patients in the present study using univariate and multivariate analyses. In the univariate analysis, anti-tumor drug treatment was significantly associated with a favorable outcome (HR 0.214; 95% CI 0.157 – 0.291; P < 0.001), while diffuse-type histology (HR 1.538; 95% CI 1.176–2.012; P = 0.002), 1 or more ECOG PS (HR 11.322; 95% CI 8.426–15.213), CAR ≥ 0.096 (HR 1.284; 95% CI 1.025–1.608; P = 0.030), NLR ≥ 3.47 (HR 1.588; 95% CI 1.266–1.992; P < 0.001), and combined value of CAR and NLR ≥ 5.02 (HR 1.382; 95% CI 1.094–1.745; P = 0.007) were significantly associated with a poor outcome.

In multivariate analysis of OS, anti-tumor drug treatment was significantly associated with a favorable outcome (HR 0.268; 95% CI 0.182–0.393; P < 0.001), while diffuse-type histology (HR 1.865; 95% CI 1.397–2.490; P < 0.001), 1 or more ECOG PS (HR 11.510; 95% CI 7.941–16.683; P < 0.001), and NLR ≥ 3.47 (HR 1.341; 95% CI 1.174–1.769; P = 0.023) was significantly associated with a poor outcome. The survival rate was not significantly associated with age, sex, disease status, metastasis site, CAR, and PNI.

Comparison between the systemic drug treatment and the BSC group

Table 3 shows the results of univariate analysis of the clinicopathological characteristics between the patients who underwent systemic drug treatment and BSC. The median survival time was significantly longer in patients who underwent systemic drug treatment than those who received BSC (14.2 months vs. 3.5 months, P < 0.001). CAR, NLR, and combined value of CAR and NLR were significantly lower in patients who underwent systemic drug treatment than those who received BSC (0.203 vs. 0.607; P = 0.049, 3.30 vs. 4.49; P = 0.004, 5.71 vs. 10.31; P < 0.001, respectively). PNI was significantly higher in patients who underwent systemic drug treatment than those who received BSC (36.1 vs. 34.1; P = 0.003).

Analysis for recurrent gastric cancer compared to initially metastatic disease

Table 4 shows the results of univariate analysis of the clinicopathological characteristics between the patients with recurrence after curative resection and initially metastatic gastric cancer. The incidence of patients who underwent systemic drug treatment was significantly higher in patients with recurrent gastric cancer than those with initially metastatic disease (85.6% vs. 73.4%, P = 0.008). CAR, NLR, and combined value of CAR and NLR were significantly lower in patients with recurrent gastric cancer than those with initially metastatic disease (0.045 vs. 0.575; P < 0.001, 2.43 vs. 4.19; P < 0.001, 2.83 vs. 9.25; P < 0.001, respectively). PNI was significantly higher in patients with recurrent gastric cancer than those with initially metastatic disease (40.6 vs. 33.2; P < 0.001).

Survival analysis of patients who underwent best supportive care

Table 5 summarizes the clinical characteristics and survival of patients who underwent the best supportive care to remove the confounding effect of chemotherapy using univariate and multivariate analyses. In multivariate analysis of OS, diffuse-type histology (HR 5.463; 95% CI 2.159 – 13.825; P < 0.001), and CA125 ≥ 42.5 U/mL (HR 2.751; 95% CI 1.220 – 6.203; P = 0.012) was significantly associated with a poor outcome. The survival rate was not significantly associated with age, sex, disease status, metastasis site, CAR, NLR, and PNI.

Discussion

We found that increased CAR and NLR were significantly associated with a poor OS, and NLR was an independent predictor of poor prognosis in patients with unresectable advanced gastric cancer, indicating that these indicators might be used as potential markers to define the prognosis of these patients. This is the first study to demonstrate the relationship between CAR and prognosis in patients with unresectable advanced gastric cancer.

In the current study, a significant positive correlation was identified between CAR and NLR. Serum albumin is produced by hepatocytes and regulated by proinflammatory cytokines and plays an important regulatory role in body fluid distribution substrate transport and acid-based physiology between the intravascular and extravascular space [22]. Circulating lymphocytes play an important immunological role in various carcinomas and their levels are associated with survival, and neutrophils contribute to inflammation by activating pro-angiogenic factors [23]. CRP is also produced by liver cells and is an inflammatory marker that plays a crucial role in tumor development and distant metastasis and tumor progression and prognosis [24,25,26]. Therefore, CAR and NLR are related to inflammation, nutrition, and immune activity, which represent the balance between inflammatory activation and regulatory factors. As shown in our results, the combined value of CAR and NLR might be a candidate for a reliable marker to predict survival for patients with unresectable advanced or recurrent gastric cancer.

Based on our results, patients with advanced gastric cancer having high CAR had worse survival times than those with low CAR. Recently, a growing amount of evidence has suggested that the CAR at diagnosis could be a favorable prognostic factor and a more reliable evaluation tool for the physiological status of cancer patients, including lung, esophageal, gastric, and colorectal cancer [10, 11, 25, 27,28,29,30,31,32]. Liu et al. reported that CAR was independently associated with OS in their retrospective analysis of 455 patients with gastric cancer undergoing curative resection [33]. In an analysis of 453 patients who underwent curative surgery for gastric cancer, Saito et al. reported that the combination of CAR and NLR was an independent prognostic indicator [10]. They used CAR and NLR cut-off values of 0.0232 and 2.43, respectively, as determined by ROC analysis; and Mao et al. also showed a significant prognostic value of these markers using CAR and NLR cut-off values of 0.38 and 3.14, respectively [10, 25]. This value is different from previous studies, which may be due to the difference in study populations. Although 0.096 and 3.47 were defined as the cut-off values of CAR and NLR in the present study, the optimal cut-off values remain unclear due to the retrospective nature of studies demonstrating the prognostic significance of these markers in cancer patients.

Multivariate analysis showed that NLR was independently related to poor survival in our cohort, which indicated the prognostic value of systemic inflammatory response markers in patients with gastric cancer. Numerous studies have demonstrated that NLR is a reliable marker associated with poor prognosis in various solid tumors [9, 10, 25]. We also confirmed that anti-tumor drug treatment and intestinal-type histology were independent poor prognostic factors of advanced gastric cancer. The parameters used by these indices can be easily calculated and routinely evaluated in laboratory tests during pretreatment diagnostic workup, which is also a simple and objective indicator.

In the results of our study, CAR, NLR, and PNI showed significantly different levels between the patients who underwent systemic drug treatment and those who received BSC. Similarly, CAR, NLR, and PNI showed significantly different levels between the patients with recurrent gastric cancer and those with initially metastatic disease. The Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG) validated a prognostic scoring index for advanced gastric cancer, in which ECOG PS ≥ 1, number of metastatic sites ≥ 2, no prior gastrectomy, and elevated alkaline phosphatase were selected [34, 35]. Generally, the patients with insufficient organ function, ECOG PS of 3 or more, or insufficient dietary intake due to cachexia were performed BSC to palliate symptoms, and the present study adopted this standard as well. Therefore, systemic inflammatory and nutritional markers such as CAR, NLR, and PNI might be worse levels in patients who underwent BSC than those who underwent systemic drug treatment.

Gastric cancer is divided into intestinal and diffuse types according to the Lauren classification [14]. In the present study, we also demonstrated that diffuse-type gastric cancer was independently associated with poor survival compared to intestinal-type cancer. This result was consistent with previous studies, which showed that histological type according to the Lauren classification was an independent prognostic factor for predicting the survival of postoperative patients with gastric cancer and unresectable advanced gastric cancer [2, 9, 36]. However, some studies analyzed the histological type of gastric cancer and found no such independent association on multivariate analysis [37, 38]. Therefore, further studies are needed to confirm the reliability and accuracy of using the histological type according to the Lauren classification as a prognostic indicator for advanced gastric cancer, because gastric cancer has a heterogeneous pathological classification.

PNI is calculated using the total lymphocyte count in peripheral blood and serum albumin levels and is an effective indicator for assessing the nutritional and immunological conditions of cancer patients [21]. It was initially developed to estimate the risk of perioperative complications such as delayed tissue repair, anastomotic leakage, and the length of postoperative hospital stay in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery [39]. Although the present study could not show the significance of using PNI for unresectable gastric cancer patients, various studies have reported that combined scoring systems, including this marker, can identify patients with a poor nutritional status to predict postoperative complications and survival [21, 39, 40].

The generalizability of the conclusions is important because the present study has a number of potential limitations and strengths. First, the present study was retrospective in nature and thus might be influenced by selection bias associated with survival data, which needs further validation by prospective studies. Second, this study could be affected by patient selection bias since it was conducted in a single institution, while it had a relatively large number of subjects. Third, the cut-off values according to ROC curve analysis for the predicted median survival time had only moderate sensitivity and specificity, which were therefore not particularly valid. Further studies with adequate statistical power, especially prospective multicenter clinical trials, are needed in routine clinical practice using CAR and NLR as predictors for the prognosis of patients with unresectable advanced gastric cancer.

In conclusion, high CAR and NLR are associated with worse survival in patients with unresectable advanced gastric cancer, suggesting that these biomarkers, with their simplicity and availability, are useful in predicting the prognosis of these patients. Notably, a high NLR is an independent unfavorable prognostic factor in such patients as well as diffuse-type histology. Further studies are required to confirm the generability of our results to improve the management of advanced gastric cancer.

References

Digklia A, Wagner AD (2016) Advanced gastric cancer: current treatment landscape and future perspectives. World J Gastroenterol 22:2403–2414

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F (2021) Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021 Feb 4. doi: https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660. Online ahead of print.

Fidler MM, Gupta S, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Bray F (2017) Cancer incidence and mortality among young adults aged 20–39 years worldwide in 2012: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 18:1579–1589

Ohtsu A, Yoshida S, Saijo N (2006) Disparities in gastric cancer chemotherapy between the East and West. J Clin Oncol 24:2188–2196

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (2021) Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2018 (5th edition). Gastric Cancer 24:1–21.

Namikawa T, Kawanishi Y, Fujisawa K, Munekage E, Iwabu J, Munekage M, Maeda H, Kitagawa H, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K (2018) Serum carbohydrate antigen 125 is a significant prognostic marker in patients with unresectable advanced or recurrent gastric cancer. Surg Today 48:388–394

Wen J, Bedford M, Begum R, Mitchell H, Hodson J, Whiting J, Griffiths E (2018) The value of inflammation based prognostic scores in patients undergoing surgical resection for oesophageal and gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 117:1697–1707

Tokunaga R, Sakamoto Y, Nakagawa S, Izumi D, Kosumi K, Taki K, Higashi T, Miyata T, Miyamoto Y, Yoshida N, Baba H (2017) Comparison of systemic inflammatory and nutritional scores in colorectal cancer patients who underwent potentially curative resection. Int J Clin Oncol 22:740–748

Namikawa T, Munekage E, Munekage M, Maeda H, Yatabe T, Kitagawa H, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K (2016) Evaluation of systemic inflammatory response biomarkers in patients receiving chemotherapy for unresectable and recurrent advanced gastric cancer. Oncology 90:321–326

Saito H, Kono Y, Murakami Y, Shishido Y, Kuroda H, Matsunaga T, Fukumoto Y, Osaki T, Ashida K, Fujiwara Y (2018) Prognostic significance of the preoperative ratio of C-reactive protein to albumin and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in gastric cancer patients. World J Surg 42:1819–1825

Kudou K, Saeki H, Nakashima Y, Kamori T, Kawazoe T, Haruta Y, Fujimoto Y, Matsuoka H, Sasaki S, Jogo T, Hirose K, Hu Q, Tsuda Y, Kimura K, Ando K, Oki E, Ikeda T, Maehara Y (2019) C-reactive protein/albumin ratio is a poor prognostic factor of esophagogastric junction and upper gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 34:355–363

Yoshida K, Yamaguchi K, Okumura N, Tanahashi T, Kodera Y (2016) Is conversion therapy possible in stage IV gastric cancer: the proposal of new biological categories of classification. Gastric Cancer 19:329–338

Namikawa T, Marui A, Yokota K, Fujieda Y, Munekage M, Uemura S, Maeda H, Kitagawa H, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K (2021) Successful conversion surgery for advanced gastric cancer with multiple liver metastases following ramucirumab plus paclitaxel combination treatment. In Vivo 35:2929–2935

Lauren P (1965) The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histoclinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 64:31–49

Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, Lordick F, Ohtsu A, Omuro Y, Satoh T, Aprile G, Kulikov E, Hill J, Lehle M, Rüschoff J, Kang YK, Investigators TT (2010) Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 376:687–697

Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, Takagane A, Akiya T, Takagi M, Miyashita K, Nishizaki T, Kobayashi O, Takiyama W, Toh Y, Nagaie T, Takagi S, Yamamura Y, Yanaoka K, Orita H, Takeuchi M (2008) S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 9:215–221

Boku N, Yamamoto S, Fukuda H, Shirao K, Doi T, Sawaki A, Koizumi W, Saito H, Yamaguchi K, Takiuchi H, Nasu J, Ohtsu A; Gastrointestinal Oncology Study Group of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group (2009) Fluorouracil versus combination of irinotecan plus cisplatin versus S-1 in metastatic gastric cancer: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 10:1063–1069

Wilke H, Muro K, Van Cutsem E, Oh SC, Bodoky G, Shimada Y, Hironaka S, Sugimoto N, Lipatov O, Kim TY, Cunningham D, Rougier P, Komatsu Y, Ajani J, Emig M, Carlesi R, Ferry D, Chandrawansa K, Schwartz JD, Ohtsu A; RAINBOW Study Group (2014) Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 15:1224–1235

Kang YK, Boku N, Satoh T, Ryu MH, Chao Y, Kato K, Chung HC, Chen JS, Muro K, Kang WK, Yeh KH, Yoshikawa T, Oh SC, Bai LY, Tamura T, Lee KW, Hamamoto Y, Kim JG, Chin K, Oh DY, Minashi K, Cho JY, Tsuda M, Chen LT (2017) Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 390:2461–2471

Shitara K, Doi T, Dvorkin M, Mansoor W, Arkenau HT, Prokharau A, Alsina M, Ghidini M, Faustino C, Gorbunova V, Zhavrid E, Nishikawa K, Hosokawa A, Yalçın Ş, Fujitani K, Beretta GD, Cutsem EV, Winkler RE, Makris L, Ilson DH, Tabernero J (2018) Trifluridine/tipiracil versus placebo in patients with heavily pretreated metastatic gastric cancer (TAGS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 19:1437–1448

Sakurai K, Ohira M, Tamura T, Toyokawa T, Amano R, Kubo N, Tanaka H, Muguruma K, Yashiro M, Maeda K, Hirakawa K (2016) Predictive potential of preoperative nutritional status in long-term outcome projections for patients with gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 23:525–533

Saito H, Kono Y, Murakami Y, Shishido Y, Kuroda H, Matsunaga T, Fukumoto Y, Osaki T, Ashida K, Fujiwara Y (2018) Prognostic significance of platelet-based inflammatory indicators in patients with gastric cancer. World J Surg 42:2542–2550

Namikawa T, Yokota K, Tanioka N, Fukudome I, Iwabu J, Munekage M, Uemura S, Maeda H, Kitagawa H, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K (2020) Systemic inflammatory response and nutritional biomarkers as predictors of nivolumab efficacy for gastric cancer. Surg Today 50:1486–1495

Kong F, Gao F, Chen J, Zheng R, Liu H, Li X, Yang P, Liu G, Jia Y (2016) Elevated serum C-reactive protein level predicts a poor prognosis for recurrent gastric cancer. Oncotarget 7:55765–55770

Mao M, Wei X, Sheng H, Chi P, Liu Y, Huang X, Xiang Y, Zhu Q, Xing S, Liu W (2017) C-reactive protein/albumin and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratios and their combination predict overall survival in patients with gastric cancer. Oncol Lett 14:7417–7424

Namikawa T, Ishida N, Tsuda S, Fujisawa K, Munekage E, Iwabu J, Munekage M, Uemura S, Tsujii S, Tamura T, Yatabe T, Maeda H, Kitagawa H, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K (2019) Prognostic significance of serum alkaline phosphatase and lactate dehydrogenase levels in patients with unresectable advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 22:684–691

Lu J, Xu BB, Zheng ZF, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lin JX, Chen QY, Cao LL, Lin M, Tu RH, Huang ZN, Zheng CH, Huang CM, Li P (2019) CRP/prealbumin, a novel inflammatory index for predicting recurrence after radical resection in gastric cancer patients: post hoc analysis of a randomized phase III trial. Gastric Cancer 22:536–545

Okugawa Y, Toiyama Y, Yamamoto A, Shigemori T, Ichikawa T, Yin C, Suzuki A, Fujikawa H, Yasuda H, Hiro J, Yoshiyama S, Ohi M, Araki T, McMillan DC, Kusunoki M (2020) Lymphocyte-to-C-reactive protein ratio and score are clinically feasible nutrition-inflammation markers of outcome in patients with gastric cancer. Clin Nutr 39:1209–1217

Ni XF, Wu J, Ji M, Shao YJ, Xu B, Jiang JT, Wu CP (2018) Effect of the C-reactive protein/albumin ratio on prognosis in advanced non-small cell lung cancer . Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 14:402–409

Liu Z, Jin K, Guo M, Long J, Liu L, Liu C, Xu J, Ni Q, Luo G, Yu X (2017) Prognostic value of the CRP/Alb ratio, a novel inflammation-based score in pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 24:561–568

Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Iseki Y, Ikeya T, Hirakawa K (2016) Prognostic significance of the preoperative ratio of C-reactive protein to albumin in patients with colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res 36:995–1001

Otowa Y, Nakamura T, Yamamoto M, Kanaji S, Matsuda Y, Matsuda T, Oshikiri T, Sumi Y, Suzuki S, Kakeji Y (2017) C-reactive protein to albumin ratio is a prognostic factor for patients with cStage II/III esophageal squamous cell cancer. Dis Esophagus 30:1–5

Liu X, Sun X, Liu J, Kong P, Chen S, Zhan Y, Xu D (2015) Preoperative C-reactive protein/albumin ratio predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for gastric cancer. Transl Oncol 8:339–345

Takahari D, Boku N, Mizusawa J, Takashima A, Yamada Y, Yoshino T, Yamazaki K, Koizumi W, Fukase K, Yamaguchi K, Goto M, Nishina T, Tamura T, Tsuji A, Ohtsu A (2014) Determination of prognostic factors in Japanese patients with advanced gastric cancer using the data from a randomized controlled trial, Japan clinical oncology group 9912. Oncologist 19:358–366

Takahari D, Mizusawa J, Koizumi W, Hyodo I, Boku N (2017) Validation of the JCOG prognostic index in advanced gastric cancer using individual patient data from the SPIRITS and G-SOX trials. Gastric Cancer 20:757–763

Wang H, Xing XM, Ma LN, Liu L, Hao J, Feng LX, Yu Z (2018) Metastatic lymph node ratio and Lauren classification are independent prognostic markers for survival rates of patients with gastric cancer. Oncol Lett 15:8853–8862

Berlth F, Bollschweiler E, Drebber U, Hoelscher AH, Moenig S (2014) Pathohistological classification systems in gastric cancer: diagnostic relevance and prognostic value. World J Gastroenterol 20:5679–5684

Mönig S, Baldus SE, Collet PH, Zirbes TK, Bollschweiler E, Thiele J, Dienes HP, Hölscher AH (2001) Histological grading of gastric cancer by Goseki classification: correlation with histopathological subtypes and prognosis. Anticancer Res 21:617–620

Kubota T, Shoda K, Konishi H, Okamoto K, Otsuji E (2020) Nutrition update in gastric cancer surgery. Ann Gastroenterol Surg 4:360–368

Park SH, Lee S, Song JH, Choi S, Cho M, Kwon IG, Son T, Kim HI, Cheong JH, Hyung WJ, Choi SH, Noh SH, Choi YY (2020) Prognostic significance of body mass index and prognostic nutritional index in stage II/III gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 46:620–625

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the colleagues of the Department of Surgery, Kochi Medical School.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: Tsutomu Namikawa. Acquisition of data: Tsutomu Namikawa, Shigeto Shimizu, Keiichiro Yokota, Nobuhisa Tanioka, Masaya Munekage, Sunao Uemura, Hiroyuki Kitagawa, and Michiya Kobayashi. Analysis and interpretation of data: Tsutomu Namikawa and Hiromichi Maeda. Drafting of manuscript: Tsutomu Namikawa. Critical revision of the manuscript: Tsutomu Namikawa and Kazuhiro Hanazaki.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kochi Medical School, Kochi, Japan (approval number: 2020–136).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants or their family included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Namikawa, T., Shimizu, S., Yokota, K. et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and C-reactive protein–to–albumin ratio as prognostic factors for unresectable advanced or recurrent gastric cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg 407, 609–621 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02356-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02356-w