Abstract

Purpose

Psychosocial working conditions—in terms of job decision authority, among others—may influence asthma self-management at work and in leisure time, as recent qualitative research has shown. We sought to statistically investigate potential relationships between job decision authority and two types of self-management behaviours: physical activity (PA) and visits to the general practitioner (GP).

Methods

We combined data from waves 1 and 2 of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) for cross-sectional analyses. The sample was restricted to participants who were employed and reported asthma but no other chronic lung disease (n = 387). The three key variables were each measured by one item. We estimated the prevalence ratios of adequate PA (i.e., more than once a week) and regular GP visits (i.e., ≥ 4 per year) according to job decision authority (low vs. high) using Poisson regression with the robust variance.

Results

We found no evidence of a relationship between job decision authority and PA. However, employees with low levels of job decision authority had a higher prevalence of reporting that they consulted their GP at least four times per year (prevalence ratio = 1.30; 95% confidence interval = 1.03–1.65).

Conclusions

This study was the first to quantitatively investigate the relationship between job decision authority and PA specifically among individuals with asthma. Our results contradict prior epidemiological studies among general working populations, which reported a positive relationship between job decision authority and PA. Our results concerning the association between low job decision authority and more GP visits are inconsistent with our qualitative findings but supported by epidemiological studies among general occupational samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Asthma can considerably affect patients physically, psychologically, and socially, and, thus, may impair their quality of life (Loerbroks et al. 2012, 2018; The global asthma report 2018). In most individuals, the illness can be well controlled though by effective self-management behaviour (Kotses and Creer 2010; The global asthma report 2018). Besides strategies to cope with acute symptoms (e.g., breathing techniques), asthma self-management, among others, covers strategies related to symptom prevention (e.g., trigger avoidance or physical exercise) and symptom monitoring (e.g., peak flow meter use or physician visits) (Global Initiative for Asthma 2018; Mammen and Rhee 2012).

Earlier qualitative research from our research group explored how working conditions may influence asthma self-management at work according to affected individuals (Heinrichs et al. 2018). In that study, employees with asthma reported that low decision authority over their tasks and when and how to complete them impaired their asthma self-management at the workplace and in leisure time (Heinrichs et al. 2018). Job decision authority is a key component in well-established work stress models: together with a second sub-scale (“skill discretion”), it forms the concept of job decision latitude (Karasek et al. 1998). In our study, working time regulations seemed to particularly affect asthma self-management in terms of symptom prevention (i.e., trigger avoidance and exercise), symptom monitoring (i.e., medical check-ups), and acute symptom management (i.e., the opportunity to take breaks, to leave work early, or to stay at home as required due to one’s asthma symptoms) (Heinrichs et al. 2018). For example, employees with asthma who experienced low levels of job decision authority reported that they (a) found it difficult to participate in regular leisure-time physical activity (PA), e.g., because of their long or irregular working hours, and (b) felt that they were less likely to see their treating physician for their asthma on a regular basis, e.g., because they had to make up for the lost hours (Heinrichs et al. 2018).

In this study, we aim to statistically examine the following hypotheses, which can be derived from prior qualitative evidence: among individuals with asthma, (1) there is a positive relationship between job decision authority and PA (i.e., employees with low job decision authority report less PA) and (2) there is a positive relationship between job decision authority and the number of physician visits (i.e., employees with low job decision authority report fewer visits).

Methods

Study population

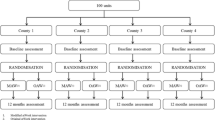

We used data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). SHARE is a panel database that contains data on health, socio-economic variables, and social factors, among others, from Europeans aged 50 and above or living with a person aged 50 and over in one household (Börsch-Supan et al. 2013). We used data from waves 1 and 2 since only those waves contained all the variables needed for our analyses. Data were collected in 2004 and 2005 in 12 countries (wave 1) and in 2005 and 2006 in 15 countries (wave 2). We combined the data from the two waves into a single data set for cross-sectional analyses. In total, 67,608 records resulted from the two waves, and the response rate was around 61% at both time points (Börsch-Supan et al. 2013). First, we removed double cases (using the data from wave 1, complemented by the data from wave 2, e.g., in case of new participants, remaining n = 37,175). Then, we reduced the sample to participants who reported asthma (remaining n = 3231)—but no other chronic lung disease diagnosed by a physician (remaining n = 2446)—and who were in employment or working as civil servants (remaining n = 505). These numbers imply that only 20.6% of the participants with asthma and no other chronic lung disease were employed or working as civil servants. This estimate is in keeping with the respective proportion in the overall sample (i.e., 25.6%) and is explained by the high percentage of retired people (47.7%) and homemakers (14.5%). After elimination of cases with missing values on the exposure, outcome, or control variables (mainly body mass index and GP visits), the final data set contained 387 records. An alternative approach had been to use wave 1 and wave 2 data to conduct prospective analyses. The number of remaining participants for such analyses was too low though (n = 84).

Measures

Job decision authority was measured by one item, which had also been used in prior studies (e.g., Loerbroks et al. 2017; Mäcken 2019): “I have very little freedom to decide how I do my work.” Possible answers were: 1: strongly agree; 2: agree; 3: disagree; 4: strongly disagree. Job decision authority was considered low when agreement was reported (answers 1 or 2) and high in case of disagreement (answers 3 or 4). The following item assessed PA: “How often do you engage in vigorous PA, such as sports, heavy housework, or a job that involves physical labour?” One of the following answers was to be selected: (1) more than once a week; (2) once a week; (3) one-to-three times a month; (4) hardly ever, or never. This single-item variable has been used in previous publications based on the SHARE data (Marques et al. 2018; Memel et al. 2016). To minimize potential misclassification bias (i.e., implying that physically inactive individuals are mistakenly classified as physically active and vice versa) (Cheval et al. 2017), we defined adequate vigorous PA, such as sports, heavy housework, or a job that involves physical labour, as “more than once a week”. Another reason for the dichotomization of PA at that cut-off (instead of using all four levels) is that systematic reviews showed that physical training at least twice a week is beneficial to asthma (Carson et al. 2013; Eichenberger et al. 2013). This was reflected most suitably by the highest measured PA level (“more than once a week”). Two consecutive items assessed the number of GP visits, as used in another SHARE-based study (Bíró 2016): “About how many times in total have you seen or talked to a medical doctor about your health?” and “How many of these contacts were with a general practitioner or with a doctor at your health care centre?”. We defined at least one visit per quarter–that is, four or more visits per year–as an adequate number of GP visits for individuals with a chronic disease such as asthma.

Data analysis

Poisson regression analyses with the robust variance using SPSS 25 were conducted to investigate the relationships of low job decision authority (reference category: high job decision authority) with reported PA (dependent variable: more than once a week) and number of GP visits (dependent variable: ≥ 4 GP visits per year) (Barros and Hirakata 2003). We initially estimated unadjusted prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), which were subsequently adjusted for wave, country, gender, age, highest educational degree, body mass index, and smoking status (never, current, and former).

Results

Sample characteristics are listed in Table 1 (n = 387). The mean age was 55.1 years (standard deviation: 5.3 years, range: 36–76 years). The sample comprised 55.8% women, and 74.7% of the participants experienced high levels of job decision authority. The latter estimate was comparable to that in the entire—and representative—SHARE sample (73.1% in wave 1 and 72.3% in wave 2). Less than half of the sample reported vigorous PA more than once a week (45.2%) and to see their GP at least four times per year (42.1%).

As shown in Table 2, there did not seem to be a relationship between job decision authority and reported PA, neither in unadjusted nor in adjusted analyses. Low job decision authority was, however, associated with a higher prevalence of reporting an adequate number of visits to the GP (≥ 4 visits per year) in both unadjusted (PR = 1.34; 95% CI = 1.06–1.71) and adjusted (PR = 1.30; 95% CI = 1.03–1.65) analyses.

Discussion

This study was the first to quantitatively investigate the relationship between job decision authority and PA specifically among individuals with asthma. We did not find evidence of a meaningful relationship between the two variables. This is not only inconsistent with our initial hypothesis derived from qualitative findings (Heinrichs et al. 2018) but also in disagreement with results from several epidemiological studies (Choi et al. 2010; Kouvonen et al. 2005, 2012). Those studies, which did not specifically focus on individuals with asthma though, suggested that increasing job decision authority may be associated with higher PA levels. However, those studies addressed leisure-time PA only, whereas, in SHARE, job-related PA was included in the item. It is unclear if or to what extent an interrelationship between the two could have affected our findings: for instance, a manual worker with high occupational PA may report less leisure-time PA while a white-collar worker may report higher leisure-time PA. Concerning cardiovascular disease, leisure-time PA was shown to lower the risk of the illness whereas occupational PA slightly increased it (the so-called PA paradox) (Ferrario et al. 2018; Li et al. 2013). However, it remains unclear if this effect would also be found among workers with asthma because some of the possible explanations for this finding are very specific for cardiovascular disease (e.g., concerning elevated heart rate and blood pressure due to occupational PA) (Holtermann et al. 2018).

We observed that low job decision authority was related to a higher prevalence of visiting the GP at least four times per year. This is inconsistent with our second hypothesis derived from qualitative findings among patients with asthma: our participants explained that they found it difficult to see their GP for their mostly quarter-annual check-ups because of their limited freedom to decide on their own working hours (Heinrichs et al. 2018). Due to this observation, we assumed that more GP visits serve primarily as an indicator of regularly monitored and likely well-controlled asthma and are associated with high job decision authority. Our results do not support this notion but are in keeping with findings from epidemiological studies among general working populations, which showed that employees with low job control were more likely to see their GP (Parslow et al. 2004; Steenbeek 2012). Our findings expand this evidence specifically to individuals with asthma. One explanation for this association could be that employees with low job decision authority experience more strain at work and may, therefore, develop health complaints (possibly due to poorer self-management while being at work) leading to more GP visits. This means that more GP visits could be seen as an indicator of ill-health.

The disagreement of the results from our study with those from our prior qualitative study could be due to the operationalization of job decision authority in the present study. In SHARE, job decision authority was measured as the “freedom to decide how I do my work”. However, in our qualitative study, participants explained that their PA and number of physician visits were in particular affected by their working time regulations (thus, when they do their work) (Heinrichs et al. 2018). In other studies using the SHARE data, job control was assessed by a combination of “I have very little freedom to decide how I do my work” (decision authority, which we used) and “I have an opportunity to develop new skills” (skill discretion) (e.g., Loerbroks et al. 2017; Mäcken 2019). As mentioned above, we deliberately decided not to combine those two items into a single measure because we aimed to specifically examine the findings from our prior qualitative study (Heinrichs et al. 2018). Participants in our earlier qualitative study never mentioned their (lacking) opportunities for skill development as a possible determinant of their asthma management. Therefore, we did not include this item in the analyses. There is evidence supporting this strategy of separating decision authority from skill discretion (Bean et al. 2015; Joensuu et al. 2012). Moreover, the differing findings may be partly due to sample differences: SHARE gathered data among a multi-country general population sample whereas our prior qualitative study was conducted among German employees with asthma who were in pulmonary rehabilitation.

Limitations

First, our study is cross-sectional and does not provide insights into whether associations are causal and if so, into the causal directions. Second, our choice to use job decision authority as an exposure variable was determined by the nature of the available data. There are other concepts related to working conditions and illness at work, which would possibly have been useful as well for our study. For instance, the concept of “adjustment latitude” by Johansson and Lundberg (2004) specifically refers to an employee’s opportunity to alter their work when not feeling well, e.g., going home early or working more slowly. Furthermore, there is the concept of “margin of manoeuvre” which alludes to the “freedom a worker has to develop different ways of working in order to meet production targets, without having adverse effects on his or her health” (Durand et al. 2009). However, adjustment latitude implies that a person is currently not feeling well whereas job decision authority also encompasses aspects which amongst others seem to influence symptom prevention (such as trigger avoidance) among employees with asthma who do not currently suffer from acute symptoms (Heinrichs et al. 2018). In addition, those two alternative concepts cover aspects of asthma self-management, above all acute symptom management such as activity modification by working more slowly or taking breaks (Heinrichs et al. 2018; Mammen and Rhee 2012). Since those concepts thus cover aspects of both our exposure variable as well as our outcome variables, they did not seem suitable to assess either one of them separately in this study. Third, the key variables were each assessed by one item only. Regretfully, common psychometric properties (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha, factorial structures), which are partly interpreted as evidence of the validity of instruments, cannot be estimated for such single-item measures. More comprehensive measures could possibly have provided more detailed insights though. For instance, it would have been worthwhile to measure occupational and leisure-time PA separately. Maybe, this approach would have confirmed the hypothesized relationships or had suggested differential effects by the type of PA documented (Ferrario et al. 2018; Holtermann et al. 2018; Li et al. 2013). Furthermore, the reasons and motivations for GP visits should have been assessed to be able to interpret the patients’ consultation-seeking behaviour. If a patient with asthma goes to see their GP for a regular check-up, the visit could be considered as appropriate asthma SMB, i.e., as a favourable event, as it was in our qualitative interview study (Heinrichs et al. 2018). If a patient needs to see their GP because their symptoms worsened, however, the visit needs to be understood as an undesired event. Moreover, we were able to only consider GP visits but no visits to pneumologists. One may assume that patients who consult specialists might display poorer disease control. Asthma is a condition, however, which is supposed to be efficiently handled in primary care (e.g., Grover and Higgins 2016). Moreover, GPs serve as gatekeepers in several countries participating in SHARE (Bíró 2016), which implies that patients are to see their GP before they may consult a specialist. Thus, bias due to the sole reliance on GP visits (i.e., selection according to disease severity) is likely limited. Fourth, since our analyses focused on chronically ill employees, healthy worker effects cannot be ruled out (Dumas et al. 2013). Fifth, asthma was assessed by self-report of physician diagnoses. Medical records would have provided more reliable information. Nonetheless, self-report information on asthma had been shown to be sufficiently reliable (Mirabelli et al. 2014). Moreover, the exclusion of participants reporting other chronic lung diseases likely reduced diagnostic confusion, e.g., between asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (Tinkelman et al. 2006).

In conclusion, we did not find evidence of a meaningful relationship between job decision authority and PA but observed that low levels of job decision authority related to a higher prevalence of visiting the GP. Further research is needed to better understand how working conditions may determine different types of asthma self-management.

References

Barros AJ, Hirakata VN (2003) Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 3:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-3-21

Bean CG, Winefield HR, Sargent C, Hutchinson AD (2015) Differential associations of job control components with both waist circumference and body mass index. Soc Sci Med 143:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.034

Bíró A (2016) Outpatient visits after retirement in Europe and the US. Int J Health Econ Manag 16:363–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-016-9191-7

Börsch-Supan A, Brandt M, Hunkler C et al (2013) Data resource profile: the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Int J Epidemiol 42:992–1001. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt088

Carson KV, Chandratilleke MG, Picot J, Brinn MP, Esterman AJ, Smith BJ (2013) Physical training for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001116.pub4

Cheval B, Sieber S, Guessous I et al (2017) Effect of early-and adult-life socioeconomic circumstances on physical inactivity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001472

Choi B, Schnall P, Haiou Y et al (2010) Psychosocial working conditions and active leisure-time physical activity in middle-aged US workers. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 23:239–253. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10001-010-0029-0

Dumas O, Le Moual N, Siroux V et al (2013) Work related asthma. A causal analysis controlling the healthy worker effect. Occup Environ Med 70:603–610. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2013-101362

Durand M-J, Vézina N, Baril R, Loisel P, Richard M-C, Ngomo S (2009) Margin of manoeuvre indicators in the workplace during the rehabilitation process: a qualitative analysis. J Occup Rehabil 19:194–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9173-4

Eichenberger PA, Diener SN, Kofmehl R, Spengler CM (2013) Effects of exercise training on airway hyperreactivity in asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 43:1157–1170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0077-2

Ferrario MM, Roncaioli M, Veronesi G et al (2018) Differing associations for sport versus occupational physical activity and cardiovascular risk. Heart 104:1165–1172. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312594

Global Initiative for Asthma (2018) Pocket Guide for asthma management and prevention (updated 2018). https://ginasthma.org/download/836/. Accessed 23 Oct 2018

Grover H, Higgins B (2016) GPs have key role in improving outcomes in acute asthma. Pract 260:15–19

Heinrichs K, Vu-Eickmann P, Hummel S, Gholami J, Loerbroks A (2018) What are the perceived influences on asthma self-management at the workplace? A qualitative study. BMJ Open 8:e022126. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022126

Holtermann A, Krause N, Van Der Beek AJ, Straker L (2018) The physical activity paradox: six reasons why occupational physical activity (OPA) does not confer the cardiovascular health benefits that leisure time physical activity does. BMJ Publ Group Ltd Br Assoc Sport Exer Med 1:1. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097965

Joensuu M, Kivimäki M, Koskinen A et al (2012) Differential associations of job control components with mortality: a cohort study, 1986–2005. Am J Epidemiol 175:609–619

Johansson G, Lundberg I (2004) Adjustment latitude and attendance requirements as determinants of sickness absence or attendance. Empirical tests of the illness flexibility model. Soc Sci Med 58:1857–1868. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00407-6

Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B (1998) The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol 3:322

Kotses H, Creer T (2010) Asthma self-management. In: Harver A, Kotses H (eds) Asthma, health and society. Springer, New York, pp 117–139

Kouvonen A, Kivimäki M, Elovainio M, Virtanen M, Linna A, Vahtera J (2005) Job strain and leisure-time physical activity in female and male public sector employees. Prev Med 41:532–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.01.004

Kouvonen A, Vahtera J, Oksanen T et al (2012) Chronic workplace stress and insufficient physical activity: a cohort study. Occup Environ Med 70:3–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2012-100808

Li J, Loerbroks A, Angerer P (2013) Physical activity and risk of cardiovascular disease: what does the new epidemiological evidence show? Curr Opin Cardiol 28:575–583. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCO.0b013e328364289c

Loerbroks A, Herr RM, Subramanian S, Bosch JA (2012) The association of asthma and wheezing with major depressive episodes: an analysis of 245 727 women and men from 57 countries. Int J Epidemiol 41:1436–1444. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys123

Loerbroks A, Karrasch S, Lunau T (2017) The longitudinal relationship of work stress with peak expiratory flow: a cohort study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 90:695–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-017-1232-0

Loerbroks A, Bosch JA, Sheikh A, Yamamoto S, Herr RM (2018) Reports of wheezing and of diagnosed asthma are associated with impaired social functioning: secondary analysis of the cross-sectional World Health Survey data. J Psychosom Res 105:52–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2017.12.008

Mäcken J (2019) Work stress among older employees in Germany: effects on health and retirement age. PLoS One 14:e0211487. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211487

Mammen J, Rhee H (2012) Adolescent asthma self-management: a concept analysis and operational definition. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol 25:180–189. https://doi.org/10.1089/ped.2012.0150

Marques A, Peralta M, Sarmento H, Martins J, González Valeiro M (2018) Associations between vigorous physical activity and chronic diseases in older adults: a study in 13 European countries. Eur J Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky086

Memel M, Bourassa K, Woolverton C, Sbarra DA (2016) Body mass and physical activity uniquely predict change in cognition for aging adults. Ann Behav Med 50:397–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9768-2

Mirabelli MC, Beavers SF, Flanders WD, Chatterjee AB (2014) Reliability in reporting asthma history and age at asthma onset. J Asthma 51:956–963. https://doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2014.930480

Parslow RA, Jorm AF, Christensen H, Broom DH, Strazdins L, Souza R (2004) The impact of employee level and work stress on mental health and GP service use: an analysis of a sample of Australian government employees. BMC Public Health 4:41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-4-41

Steenbeek R (2012) The importance of job characteristics in determining medical care-seeking in the Dutch working population, a longitudinal survey study. BMC Health Serv Res 12:294. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-294

The global asthma report 2018 (2018) Auckland, New Zealand: Global Asthma Network. http://globalasthmareport.org/Global%20Asthma%20Report%202018.pdf. Accessed 23 Oct 2018

Tinkelman DG, Price DB, Nordyke RJ, Halbert R (2006) Misdiagnosis of COPD and asthma in primary care patients 40 years of age and over. J Asthma 43:75–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770900500448738

Acknowledgements

This paper uses data from SHARE Waves 1 and 2 (DOIs: https://doi.org/10.6103/share.w1.610, https://doi.org/10.6103/share.w2.610), see Börsch-Supan et al. (2013) for methodological details.

Funding

The SHARE data collection has been primarily funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812), and FP7 (SHARE-PREP: No. 211909, SHARE-LEAP: No. 227822, SHARE M4: No. 261982). Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064, HHSN271201300071C), and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org). Our work was supported by refonet—Rehabilitation Research Network of the German Pension Fund Rhineland, grant number 14006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Waves 1 and 2 received ethical approval by the ethics committee of the University of Mannheim, Germany.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Heinrichs, K., Li, J. & Loerbroks, A. General practitioner visits and physical activity with asthma—the role of job decision authority: a cross-sectional study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 92, 1173–1178 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-019-01456-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-019-01456-x