Abstract

Purpose

To determine the prevalence of and identify factors associated with visual impairment and blindness in institutionalized elderly in Germany.

Methods

In this prospective multicenter cross-sectional study, ophthalmic health care need and provision were investigated in institutionalized elderly in 32 nursing homes in Germany. All participants underwent a standardized examination including medical and ocular history, refraction, visual acuity testing, tonometry, biomicroscopy, and dilated funduscopy. A standardized questionnaire was used to identify factors associated with eye healthcare utilization, visual impairment and/or blindness.

Results

Visual acuity of 566 (94.3%; 413 women and 153 men) of a total of 600 institutionalized elderly was determined. Mean age of the included patients was 82.9 years (± 9.8). Of all participants, 30 (5.3%; 95% CI 3.4–7.2%) were blind and 106 (18.7%; 95% CI 15.5–21.9%) were moderately or severely visually impaired according to the World Health Organization definition. The 136 blind and moderately or severely visually impaired participants were older (OR, Odds Ratio = 1.1, 95% CI 1.0–1.1; p < 0.001), and more likely to have reduced mobility (OR = 12.6, 95% CI 2.8–57.6; p = 0.001).

Conclusion

A high proportion of blindness and visual impairment was found amongst nursing home residents. Age and reduced mobility were factors associated with an increased likelihood of blindness and visual impairment. Any surveys of blindness and visual impairment excluding nursing homes may considerably underestimate the prevalence of visual impairment and blindness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Population aging will lead to a substantial increase in visual impairment and blindness as many causes of vision loss are age-related [1]. With increasing age, a growing proportion of people is cared for in nursing homes, which is why visual impairment and blindness are particularly frequent amongst institutionalized elderly [2,3,4].

Elderly persons living in nursing homes have a high prevalence and incidence of blindness and visual impairment for a number of reasons including age [5, 6], reduced independence leading to institutionalization [7], lack of access to services [8], chronic age-related diseases [9, 10] and dementia [7, 11, 12].

Knowledge of factors associated with visual impairment and blindness amongst this hard-to-reach group is essential. As this population will grow steeply in the next decades, health services must be planned according to need [13,14,15]. These include services to prevent avoidable visual impairment, the use of visual aids, and the adjustment of the living environment to the needs of visually impaired and blind institutionalized elderly, as their mobility and orientation are affected by their visual impairment [16].

In order to substantiate this for Germany, the OVIS (Ophthalmologische Versorgung in Seniorenheimen, German for: Ophthalmological care in nursing homes) study was initiated, which was implemented during 2014–2016. This study investigated factors associated with visual impairment and blindness in institutionalized elderly in order to allow for more tailored eye healthcare planning and provision.

Patients and methods

Study design and participants

The OVIS study was a multicenter cross-sectional study and was performed amongst residents of nursing homes from 2014 to 2016 nationwide in Germany. The study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by all local ethic committees. Informed consent was obtained from each participant or their legal guardian after explanation of the nature and possible consequences of the study.

In Germany, a broad spectrum of homes and residences for the elderly exist, offering a very wide range of individually adjusted care and support. In the OVIS study, only residents in need of constant nursing care provided by examined nursing staff were included (classified into level of care 0 to 3 according to German regulations pertaining to nursing care insurance, in German Pflegestufe 0–3). The higher the level of care, the more support is needed [17].

All university and major eye hospitals within Germany were invited to participate in this study. Of a total of 38 contacted centers, 14 (37.6%) agreed to participate as study centers. Nursing homes located close (radius of 50 km) to these study centers were contacted and invited to participate. Response rate was variable. Of a total of 73 contacted nursing homes, 32 (43.8%) agreed to participate. Interviews and examinations were performed by ophthalmologists and orthoptists.

All institutionalized elderly people living in the 32 nursing homes were invited to participate. Out of a total of 3127 institutionalized elderly people, 607 (19.4%) agreed to participate. Three participants were excluded due to missing data, two were only in short-term care and two were younger than 50 years, leaving a total of 600 subjects.

Data on ophthalmic health care need and provision, i.e., barriers to ophthalmic health care, was already published in 2017 [15].

Examination

The standardized examination was conducted as previously described in the nursing homes and included a detailed medical and ocular history, refraction, visual acuity testing, tonometry, biomicroscopy, and dilated funduscopy [15].

Detailed history was obtained by interviewing each participant or, in cases of inability to respond to interview questions, their carers. The standardized interview included demographic characteristics, medical and ophthalmic history, the use of eye-care and general medical services, self-reported problems with vision, and a variety of other variables. Self-reported problems with vision were captured by a standardized questionnaire with Yes/No answer options. Medical conditions including ophthalmic history were also self-reported, for which we used standardized questions as well as an open-ended question at the end of the interview which allowed participants to report any medical issue not covered. The questionnaire was interviewer-administered. Visual acuity was measured as follows: first, presenting visual acuity using a Snellen chart at 5 m distance with the subject’s own habitual distance correction (that is, eyeglasses or contact lenses, if any) and then, best corrected visual acuity using autorefraction was assessed. Visual field deficits—in the absence of a meaningful examination—could not be systematically taken into account.

Definitions of blindness and visual impairment levels

As the definition of blindness and visual impairment differs widely around the world, we used the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for blindness and visual impairment [18], which define seven categories of visual impairment: WHO visual impairment category 0 or mild or no visual impairment refers to a best-corrected visual acuity of equal to or better than 6/18 (Snellen 20/60) in the better eye, WHO visual impairment category 1 or moderate visual impairment refers to a best-corrected visual acuity of less than 6/18 (Snellen 20/60) in the better eye, and equal to or better than 6/60 (Snellen 20/200). Severe visual impairment or WHO visual impairment category 2 is defined as best-corrected visual acuity of less than 6/60 (Snellen 20/200) and equal to or better than 3/60 (Snellen 20/400) in the better eye. WHO visual impairment categories 3 to 5 are subsumed as blindness, where category 3 implies a best-corrected visual acuity of less than 3/60 (Snellen 20/400) and equal to or better than 1/60 (Snellen 20/1200), category 4 a best-corrected visual acuity of less than 1/60 (Snellen 20/1200) and at least light perception, and category 5 no light perception, all in the better eye. WHO visual impairment category 9 refers to undetermined or unspecified visual acuity.

Statistical analysis

Pseudonymized data were collected using a paper-based case report form (CRF) and entered into an electronic data base. A random sample of 20% of the CRF data was double-entered and checked manually for errors. Data were also checked for plausibility and missing or wrong data were queried and corrected. For the analysis, all visual acuity data were converted into logMAR.

All data were first analyzed descriptively using appropriate absolute and relative frequencies for categorical data and medians and quartiles/means and standard deviations for continuous data. Exploratory analyses were performed by means of the Student’s t test, the Kruskal-Wallis test (continuous data) and the Pearson’s chi-squared test (categorical data). Factors found univariately associated with moderate or severe visual impairment or blindness were evaluated by means of multiple logistic regression modeling (forward model selection based on Likelihood Ratio tests); results of the exploratory model building were then described by factor-wise odds ratio estimates with nominal 95% confidence interval (i.e., not formally adjusted for multiplicity) and corresponding p values of Wald tests. The Nagelkerke R2 served as summary indicator of achieved model fit; p values less than 0.05 were considered as indicators of locally statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed by means of the SPSS software package Statistics 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Six-hundred participants fulfilled the inclusion criteria of the study. Of these, visual acuity could be collected in 566 participants (94.3%). Of the participants with visual acuity data, 413 (73.0%) were female and 153 (27.0%) male. Mean age was 82.9 years (± 9.8). In this cohort, dementia was known in 26.9% of the elderly. 5.7% had the highest German level of care (level 3), and 2.3% of the participants were found to be bedridden.

In 34 participants (5.7%), visual acuity was not assessable due to medical reasons such as severe dementia. Mean age of these 34 participants was 82.6 years (± 9.6), which was not significantly different to the mean age of the other 566 participants. Of these 34 participants, 38.4% were male, 61.8% were known to have dementia, 46.7% had the highest German level of care, and 26.5% were bedridden.

When assessing visual acuity in the better eye with the participants’ own habitual spectacle correction if available, the number of participants with moderate visual impairment (WHO category 1, as defined in methods), severe visual impairment (WHO category 2), and blindness (WHO categories 3–5) was 128 (22.6%), 14 (2.5%), and 31 (5.5%), respectively. When assessing best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) using an autorefractor, the number of participants with moderate visual impairment, severe visual impairment, and blindness decreased to 95 (16.8%), 11 (1.9%), and 30 (5.3%), respectively (Table 1). Uncorrected refractive error was thus the cause of visual impairment in 36 (25.4%) participants, and legal blindness in one (3.2%) participant (Table 2).

Of the 142 participants with either moderate or severe visual impairment on BCVA examination, age-related macular degeneration (AMD) of any stage was present in 60 (42.3%), late stage AMD in 25 (17.6%), any cataract in 66 (46.5%), clinically relevant cataract in 55 (38.7%), glaucoma in 16 (11.3%), and other retinal or optic nerve diseases in 12 (8.4%). In the 31 blind participants, any AMD was detected in 18 (58.1%), late stage AMD in 13 (41.9%), any cataract 12 (38.7%), clinically relevant cataract in 6 (19.4%), glaucoma in 5 (16.1%), and other retinal or optic nerve diseases in 7 (22.6%) (Table 2).

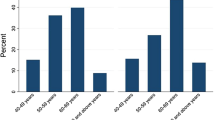

The rate of previous cataract surgery increased markedly with age. 10.9% of all participants in the age group of 60 to 69 years were pseudophakic, 30.0% for 70 to 79 year-olds, 54.4% in 80 to 89 year-olds, and 72.9% in 90 year-olds and above (p < 0.001). Mean visual acuity of the better eye of pseudophakic participants was 0.36 logMAR (± 0.44) vs. 0.42 logMAR (± 0.46) in phakic participants (p = 0.133).

The 136 participants with moderate or severe visual impairment or blindness, excluding refractive causes, were older (86.1 years ± 7.7 vs. 82.0 ± 10.1; p < 0.001), had a higher level of care (p < 0.001), and were more likely to be bedridden (p < 0.001) compared to the 430 participants with mild visual impairment or no visual impairment (Table 3).

Via multiple regression modeling (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.15 as an indicator of encouraging model fit), factors showing univariate association with moderate or severe visual impairment, were re-evaluated: higher level of care, poor physical condition (self-reported), and dementia were not significantly associated with at least moderate visual impairment or blindness any more, whereas being bedridden (OR, Odds Ratio = 12.6, 95% CI, 2.8–57.6, p = 0.001) and age (OR = 1.1, 95% CI, 1.0–1.1, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with at least moderate visual impairment or blindness (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we found a high percentage of moderate or severe visual impairment and blindness among institutionalized elderly which was mostly due to age-related eye diseases such as AMD, cataract and glaucoma. The rate of age-related eye diseases increased steeply with age, except for cataract, where the rate of cataract surgery increased with age. Being bedridden and of reduced mobility, higher age and dependency on assistance with activities of daily living were highly associated with moderate or severe visual impairment and blindness. These results indicate that institutionalized elderly have an increased need for eye healthcare provision as well as multiple barriers which impede service provision and access.

With 5.3% blind and 18.7% moderately or severely visually impaired institutionalized elderly in our study, there seems to be a considerable excess of blindness and visual impairment in this population compared to non-institutionalized populations 75 years and older with approximately 1% prevalence of blindness and 5% of visual impairment [19,20,21]. In fact, we found roughly five times as much visual impairment and blindness in institutionalized elderly compared to prevalence rates reported for community dwelling elderly. Our numbers are consistent with the Melbourne Visual Impairment Project (VIP) institutional cohort, conducted in 1995, and the Baltimore nursing home study, conducted from 1988 to 1989 [2, 3]. Thus, overall population trends of decreasing blindness and visual impairment do not translate to the institutionalized elderly [20]. This finding is consistent with the results of a mathematical model developed by Limburg and Keunen, which did not show any decrease in blindness or low vision in this vulnerable subgroup between 2008 and 2020 [22].

As ophthalmologists do not regularly visit nursing homes and transport and lack of support were the main barriers to accessing healthcare providers [15], novel models of healthcare provision need to be thought of for this hard-to-reach population. These could include but should not be limited to eye screenings by trained medical personnel or nurses, training of nursing home staff in detecting and managing visual impairment, and a better adjustment of nursing homes as such to cater to a visually impaired population. Additionally, access to cataract surgery and refractive corrections (i.e., glasses or other visual aids) should be facilitated as these are very cost-effective options to easily reduce visual impairment.

Our finding that AMD is the leading disease associated with moderate or severe visual impairment in the elderly is consistent with epidemiological data from other reports from high-income countries [2, 5, 21, 23, 24]. In the Baltimore nursing home study, AMD causing legal blindness (defined as a BCVA of equal to or less than Snellen 20/200 in the U.S.) was observed in 20% of the Caucasian participants [3]. In the Blue Mountains Eye study, late AMD was the cause of blindness (defined as a BCVA of equal to or less than Snellen 20/200 in Australia) affecting one or both eyes of 12% of residents [4]. With 44%, the VIP institutional cohort also found AMD to be the leading cause of moderate or severe visual impairment [2]. The Rotterdam Eye study also reported AMD to be the main cause of blindness in people aged 75 years and older [21]. Consistent with these published data, we found late stage AMD to cause 40.0% of blindness in our cohort.

The strengths of our study include its large sample size with data from 32 different nursing homes, thus providing a broad and supraregional overview of visual impairment and blindness in institutionalized elderly in Germany. In this study, however, we likely underestimated the proportion of moderate or severe visual impairment and blindness as visual acuity was not performed in the very frail participants. Furthermore, a double-positive selection bias is likely, since healthier and more active nursing home residents as well as more motivated and caring nursing homes more likely agreed to participate in this study. As such, we did not assess a representative sample of nursing homes or their residents in this study and results need to be interpreted keeping this in mind. In addition, we are unable to report anything about persons refusing to participate as no data could be collected, thus no statements on how general or eye health or present visual impairment might have impacted the decision to participate are possible. Considering available data, the mean age (83 years) of the participants in our study is similar to the mean age in nursing homes in Germany (82 years), indicating that our sample might be comparable in its age distribution to the overall nursing home population in Germany [25]. Further study limitations are that our analysis of visual impairment was based on visual acuity alone, as visual field was not assessed. Due to the study’s cross-sectional design, we were unable to determine causal relationships. Accurate subjective assessment of visual acuity was challenging in this vulnerable population due to dementia and other diseases restricting cognitive function and communication. Similar experiences with difficult examination conditions were also described in other studies [2,3,4].

In conclusion, we found a high proportion of blindness and moderate to severe visual impairment amongst nursing home residents in Germany. Blindness and visual impairment increased with age, reduced mobility and increased need for assistance with activities of daily living, likely due to reduced access to ophthalmological care. These factors should be considered when planning a more tailored eye healthcare provision for these hard-to-reach populations in need in the future.

Change history

06 March 2019

The original version of this article inadvertently contained a mistake. Authors incorrectly listed in PDF version while correctly presented in the html version.

References

Bourne RRA, Flaxman SR, Braithwaite T et al (2017) Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 5(9):e888–e897. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30293-0

VanNewkirk MR, Weih LA, McCarty CA et al (2000) Visual impairment and eye diseases in elderly institutionalized Australians. Ophthalmology 107(12):2203–2208. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00459-0

Tielsch JM, Javitt JC, Coleman A et al (1995) The prevalence of blindness and visual impairment among nursing home residents in Baltimore. N Engl J Med 332(18):1205–1209. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199505043321806

Mitchell P, Hayes P, Wang JJ (1997) Visual impairment in nursing home residents: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Med J Aust 166(2):73–76

Finger RP, Fimmers R, Holz FG, Scholl HPN (2011) Prevalence and causes of registered blindness in the largest federal state of Germany. Br J Ophthalmol 95(8):1061–1067. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2010.194712

Varma R, Vajaranant TS, Burkemper B et al (2016) Visual impairment and blindness in adults in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol 134(7):802. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.1284

Gaugler JE, Yu F, Krichbaum K, Wyman JF (2009) Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Med Care 47(2):191–198. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818457ce

Thibault L, Kergoat H (2016) Eye care services for older institutionalised individuals affected by cognitive and visual deficits: a systematic review. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 36(5):566–583. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12311

Garin N, Olaya B, Lara E et al (2014) Visual impairment and multimorbidity in a representative sample of the Spanish population. BMC Public Health 14(1):815. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-815

Mojon-Azzi SM, Sousa-Poza A, Mojon DS (2008) Impact of low vision on well-being in 10 European countries. Ophthalmologica 222(3):205–212. https://doi.org/10.1159/000126085

Rogers MAM, Langa KM (2010) Untreated poor vision: a contributing factor to late-life dementia. Am J Epidemiol 171(6):728–735. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp453

Bowen M, Edgar DF, Hancock B et al (2016) The prevalence of visual impairment in people with dementia (the PrOVIDe study): a cross-sectional study of people aged 60–89 years with dementia and qualitative exploration of individual, carer and professional perspectives. Heal Serv Deliv Res 4(21):1–200. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr04210

Hoffmann W, van den Berg N, Stenzel U et al (2014) Demografischer Wandel. Ophthalmologe 53(5):428–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00347-013-2923-x.

Wolfram C, Pfeiffer N (2012) Weißbuch zur Situation der ophthalmologischen Versorgung in Deutschland. DOG Deutsche Ophthalmologische Gesellschaft, München

Fang PP, Schnetzer A, Kupitz DG et al (2017) Ophthalmologische Versorgung in Seniorenheimen: Die OVIS-Studie. Ophthalmologe 114(9):818–827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00347-017-0557-0

Swenor BK, Muñoz B, West SK (2013) Does visual impairment affect mobility over time? The Salisbury Eye Evaluation study. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54(12):7683–7690. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-12869

Gräßel E, Donath C, Lauterberg J et al (2008) Demenzkranke und pflegestufen: Wirken sich krankheitssymptome auf die einstufung aus? Gesundheitswesen 70(3):129–136. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1062733

World Health Organization (2016) ICD-10 Version: 2016. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en#!/H53-H54. Accessed 9 May 2018

Finger RP (2007) Blindheit in Deutschland: Dimensionen und Perspektiven. Ophthalmologe 104(10):839–844. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00347-007-1600-3

Finger RP, Bertram B, Wolfram C, Holz FG (2012) Blindness and visual impairment in Germany: a slight fall in prevalence. Dtsch Arztebl Int 109(27–28):484–489. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2012.0484

Klaver CC, Wolfs RC, Vingerling JR et al (1998) Age-specific prevalence and causes of blindness and visual impairment in an older population: the Rotterdam study. Arch Ophthalmol 116(5):653–658

Limburg H, Keunen JEE (2009) Blindness and low vision in the Netherlands from 2000 to 2020 — modeling as a tool for focused intervention. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 16(6):362–369. https://doi.org/10.3109/09286580903312251

Newland HS, Hiller JE, Casson RJ, Obermeder S (1996) Prevalence and causes of blindness in the South Australian population aged 50 and over. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 3(2):97–107

Bourne RRA, Jonas JB, Bron AM et al (2018) Prevalence and causes of vision loss in high-income countries and in Eastern and Central Europe in 2015: magnitude, temporal trends and projections. Br J Ophthalmol 102(5):575–585. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311258

Kleina T, Horn A, Suhr R, Schaeffer D (2017) Zur Entwicklung der ärztlichen Versorgung in stationären Pflegeeinrichtungen. Ergebnisse einer empirischen Untersuchung. Das Gesundheitswes 79(05):382–387. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1549971

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ernst und Bertha Grimmke Foundation, Germany (PPL and TUK).

Funding

The Department of Ophthalmology, University of Bonn, received research funding from the Stiftung Auge (German Eye Foundation) of the German Ophthalmological Society (DOG) with support of Bayer and Novartis for the OVIS study. The Medical Biometry and Epidemiology Unit of Witten/Herdecke University received research funding from the University of Bonn (Eye Hospital) for the methodological counseling of this investigation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

S. Thiele reports personal fees from Carl Zeiss MediTec, Heidelberg Engineering, and Optos, outside the submitted work. T. U. Krohne reports personal fees from Alimera Sciences, Bayer, Heidelberg Engineering, and Novartis, outside the submitted work. F. Ziemssen has received honoraria for consultation and research from Alimera, Allergan, Bayer, Biogen, MSD, Novartis, NovoNordisk and Roche, none was related to the topic. F.G. Holz reports personal fees from Acucela, Allergan, Bayer, Bioeq, Boehringer Ingelheim, Carl Zeiss MediTec, Genentech/Roche, Heidelberg Engineering, Merz, NightstarX, Novartis, Optos, Pixium and Thea, outside the submitted work. R. P. Finger reports personal fees from Bayer, Opthea, Santen, Novartis, Retina Implant and Novelion, outside the submitted work.

None of the sponsors had any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. None of the authors has any proprietary or competing interests to disclose.

Research involving human participants

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the local ethic committees and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants or their legal guardians included in the study.

Appendix

Appendix

Contributing Centers and Members Participating in the OVIS Study

-

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Frankfurt, Germany: Prof. Dr. Thomas Kohnen, Dr. Lubka Naycheva, Maximilian Jochem

-

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Freiburg, Germany: Prof. Dr. Thomas Reinhard, Prof. Dr. Daniel Böhringer, Dr. Diana Engesser, Prof. Dr. Wolf Lagrèze, Claudia Müller, Carolin Wolff, Jessica Schmitz

-

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Gießen, Germany: Prof. Dr. Birgit Lorenz, Chrysanthi Papadopoulou-Laiou, Kerstin Holve, Silke Schweinfurth

-

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Göttingen, Germany: Prof. Dr. Hans Hoerauf, Dr. Wiebke Schwarz

-

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Hamburg, Germany: Prof. Dr. Martin Spitzer, PD Dr. Lars Wagenfeld, Paul Bertram

-

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Heidelberg, Germany: Prof. Dr. Gerd Auffarth, Branka Gavrilović

-

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Cologne, Germany: Prof. Dr. Claus Cursiefen, Dr. Friederike Schaub, Anna Lentzsch, Dr. Gerhard Welsandt

-

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Magdeburg, Germany: Prof. Dr. Hagen Thieme, Dr. Melanie Weigel, Diyala Hidaya, Angela Ehmer

-

Department of Ophthalmology, Ludwig-Maximilians University Munich, Germany: Prof. Dr. Siegfried Priglinger, Dr. Bettina von Livonius, Carina Drexler, Jessica Semmelsberger

-

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Münster, Germany: Prof. Dr. Nicole Eter, PD Dr. Florian Alten, Annika Sigleur, Dorothee Sieber, Andrea Bräutigam, Friederike Härter, Adeline Adorf

-

Department of Ophthalmology, St. Franziskus-Hospital Münster, Germany: Prof. Dr. Daniel Pauleikhoff, Dr. Angela Robering

-

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Regensburg, Germany: Prof. Dr. Horst Helbig, Dr. Caroline Brandl

-

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Tübingen, Germany: Prof. Dr. Focke Ziemssen, Dr. Daniel Röck

-

Institute for Medical Biometry and Epidemiology, University of Witten/Herdecke, Germany: Prof. Dr. Frank Krummenauer, Sabrina Tulka, M. Sc.

-

Department of Ophthalmology, University of Bonn, Germany: Prof. Dr. Frank G. Holz, Prof. Dr. Robert P. Finger, Prof. Bettina Wabbels, Dr. David. G. Kupitz, Dr. Arno P. Göbel, Dr. Julia Steinberg, Dr. Petra P. Larsen, Anne Schnetzer, Bianka Kobialka, Beate Prinz, Danielle Kutten, Pia Schneider, Olivia Toczko, Thanushiya Yoganathan

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Larsen, P.P., Thiele, S., Krohne, T.U. et al. Visual impairment and blindness in institutionalized elderly in Germany. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 257, 363–370 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-018-4196-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-018-4196-1