Abstract

Purpose

Continuous epidural infusion and programmed intermittent epidural boluses are analgesic techniques routinely used for pain relief in laboring women. We aimed to assess both techniques and compare them with respect to labor analgesia and obstetric outcomes.

Methods

After Institutional Review Board approval, 132 laboring women aged between 18 and 45 years were randomized to epidural analgesia of 10 mL of a mixture of 0.1% bupivacaine plus 2 µg/mL of fentanyl either by programmed intermittent boluses or continuous infusion (66 per group). Primary outcome was quality of analgesia. Secondary outcomes were duration of labor, total drug dose used, maternal satisfaction, sensory level, motor block level, presence of unilateral motor block, hemodynamics, side effects, mode of delivery, and newborn outcome.

Results

Patients in the programmed intermittent epidural boluses group received statistically less drug dose than those with continuous epidural infusion (24.9 vs 34.4 mL bupivacaine; P = 0.01). There was no difference between groups regarding pain control, characteristics of block, hemodynamics, side effects, and Apgar scores.

Conclusions

Our study evidenced a lower anesthetic consumption in the programmed intermittent boluses group with similar labor analgesic control, and obstetric and newborn outcomes in both groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Labor is one of the most painful experiences a woman can undergo during her life [1]. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists mention that under no circumstance it is acceptable for a woman to feel pain, and they consider maternal request as a sufficient reason to provide pain relief by the medical staff [2]. In fact, pain has been proven to affect maternofetal physiology and neuropsychology [3]. Therefore, pain relief during labor is an essential part of practice since it helps to decrease the negative impact on both mother and baby [4].

In order to achieve adequate pain relief, different analgesic techniques such as continuous epidural infusion (CEI) and patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) have been described [5]. Both techniques have been effective to control pain during labor and delivery. Studies on CEI have shown that it provides adequate control of analgesia for labor and delivery and that it has been better than other techniques such as single-shot IV opioids [6].

A newer technique of analgesia maintenance, programmed intermittent epidural boluses (PIEB), has been compared to CEI. A meta-analysis by George et al. compared PIEB to CEI finding a higher maternal satisfaction score and less anesthetic consumption with PIEB [7]. However, no final conclusions were drawn and more research on this topic was advised.

Previous randomized controlled trials from this meta-analysis had a limitation. Either they used non-commercial PIEB devices; or intermittent epidural boluses were administered manually [8]. This study aimed to overcome this limitation.

Materials and methods

This was a prospective, randomized, controlled, single blind, and parallel clinical trial. It was approved on May 2015 by the Corporate Committee of Ethics in Research (CCEI-3413-2015) and carried out at Hospital Universitario Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá over a 1-year period. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02510287).

Written informed consent was obtained before enrolling patients. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were laboring term women aged between 18 and 45 years requiring epidural analgesia. Patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status ≥III, allergy to local anesthetics, hemodynamic instability, chronic use of analgesics, mental disease, pregnancy related disease/high obstetric risk, or with any neuraxial contraindication were excluded.

Once the patient requested epidural analgesia, the attending anesthesiologist proceeded according to protocol: non-invasive blood pressure measurement, heart rate and pulse oximetry monitors, and a 500 cc co-load of intravenous lactate ringer. The epidural catheter was placed 7 cm deep in all patients. Each patient received an initial loading dose of 10 mL of 0.1% bupivacaine (2 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine plus 50 µg/mL of fentanyl in 7 mL of 0.9% normal saline). Next, patients were randomized according to a computer generated sequence to analgesia with either PIEB or CEI with a 1:1 allocation ratio. The randomization sequence was only known by the research assistant and the nurse staff in charge of drug administration. Neither the patient nor the attending anesthesiologist nor the outcome assessor knew the randomization sequence.

Patients in the PIEB group received every hour a 10 mL bolus of a mixture of 0.1% bupivacaine plus 2 µg/mL of fentanyl in 0.9% normal saline with the first PIEB bolus given 1 h after the initial loading dose. Patients in the CEI group were administered a continuous infusion of 10 mL/h of the same mixture started immediately after the initial loading dose. For both groups, 10 mL rescue boluses (RB) of the same mixture were available as needed by the patient and programmed in the pump by the obstetric nurse. She accessed the pump using a security access code that was meant to avoid bolus application by the patient or any other health personnel. There was no limit for the number of RB administered. The epidural pump Sapphire™ Epidural Infusion Pump Kit was used for automated anesthetic administration (Sapphire Pump, Hospira, Lake Forrest, IL, USA). This epidural pump allows programmed intermittent epidural bolus administration with a maximal bolus dose infusion speed of 200 mL/h. However, the pump was set to administer bolus at an infusion speed of 125 mL/h.

The following data were recorded:

-

1.

Before initial dose: cervical dilation, pain level with Verbal Analogue Scale (VAS), and hemodynamics. The VAS ranged from 0 (no pain) to 10 cm (worst pain ever).

-

2.

At 15 min post-epidural and at every following hour until delivery: sensory level as assessed by highest dermatomal block to cold stimulus, motor block level as assessed by modified Bromage scale (0: no block, 1: partial, 2: almost complete, 3: complete), quality of analgesia as assessed by VAS, maternal satisfaction as assessed by hourly Verbal Rating Scale (VRS), unilateral motor block, and hemodynamics (blood pressure and heart rate). The VAS and VRS assessment was done hourly, at the time of bolus administration, but the assessment evaluated the previous hour.

-

3.

At the time of occurrence: side effects such as nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and hypotension.

-

4.

After delivery: newborn outcome as assessed by Apgar at 1, 5, and 10 min. Duration of labor (once epidural was given), total drug dose used, and mode of delivery.

The primary endpoints were the differences in pain control (VAS) between both groups. Secondary outcomes were patient satisfaction level, total drug dose used, incidence of side effects, changes in hemodynamic status, and impact of analgesia on the Apgar score.

Statistical analysis

Epi Info statistical software, version 7.1.4 (CDC; Atlanta, GA, USA) was used to calculate sample size to detect a 10% reduction in the difference of means of breakthrough pain between the two groups given a statistical power of 80%, a two-tailed alpha error of 5% and an expected 10% of patient withdrawal rate. Assuming a mean difference, a total of 132 patients (66 per group) were obtained. Variables were described according to their normal or non-normal distribution with descriptive statistics or non-parametric statistics, respectively. A P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

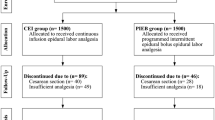

Two hundred patients were screened but 68 either declined to participate or did not meet inclusion criteria. One hundred thirty-two were finally recruited and randomized from June 2015 to May 2016. A total of 132 patients were included in the study. Four of the datasets were incomplete, finally enrolling 128 women, 64 in each group (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows patient demographic and obstetric characteristics. Both groups of patients had similar characteristics (P ≥ 0.05).

78% of the women had an initial severe VAS (≥7) in both groups. There was no significant difference regarding VAS between groups as seen on Table 2. At the first hour, 6.25% from the PIEB group remained with severe pain vs. 14.1% from the CEI group (P = 0.57). VAS analysis by parity within each group was similar for CEI and PIEB groups (P = 0.55 and P = 0.22, respectively). Figure 2 shows the percentage of women with breakthrough pain control (VAS ≥ 4) from the moment of epidural request until the fourth hour of follow-up (P = 0.82). Maternal satisfaction VRS was similar for both groups at each time assessed (Table 3). Cut-off points for VRS were considered as satisfied if the score was ≥7 and unsatisfied if the score was <7.

In regard to anesthetic consumption (Table 4), a statistical significant difference was found for RB between both groups (P = 0.011). The bupivacaine total dose was statistically significantly lower for the PIEB group (P = 0.013).

Characteristics of block include sensory level, motor level, and the presence of unilateral motor block (Table 5). There was no difference in sensory block with dermatomal block to cold stimulus varying between T6 and T12 in both groups at the different times measured (data not shown in table). Presence of motor unilateral block in both groups was not statistically different (P > 0.05). Hemodynamic changes are shown in Fig. 3. Heart rate and arterial pressure were not statistically different between groups.

Regarding the incidence and time of occurrence of side effects, there was no significant statistical difference. Overall incidence of nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and hypotension in both groups was of 17.18% in the PIEB group vs. 21.88% in the CEI group (Table 6).

Newborn outcome showed no significant statistical difference on Apgar at 1, 5, and 10 min after birth (Table 7). Obstetric outcomes regarding labor type and duration of labor were similar between groups (Table 8).

Discussion

Our primary outcome was efficacy of pain control by PIEB and CEI on laboring term women. We found that there was no statistical difference with both groups having similar pain scores at different times assessed. Most studies have been done on nulliparous women, while few have been done on multiparous women. The study conducted by Wong et al. on multiparous women found similar labor pain in PIEB and CEI groups [9]. In fact, they attributed this result to PCEA for breakthrough pain. Our study, which allowed nulliparous as well as multiparous women to request RB, had no difference on pain control when performing subgroup analysis.

Among secondary outcomes assessed were maternal satisfaction, total drug consumption, hemodynamics, side effects, newborn outcome, mode of delivery, and duration of labor.

Maternal satisfaction measures overall satisfaction with care provided [10]. It relies on pain control, but also on much more as follows: side effects, adequate sensory and motor block, and emotional dimension. Previous studies have found a greater maternal satisfaction in those women who received PIEB [7]. However, we found no significant statistical difference on satisfaction scores between groups. Access to RB immediately after patient request allowed for adequate control of pain influencing perhaps maternal satisfaction.

We found a significant greater anesthetic consumption in the CEI group. This was due to the request of 2.1 times more RB in the CEI group and almost half of the women assigned to this group needed at least one RB. The relevance of this finding relies on the disadvantage of RB increasing the workload for the medical staff and may delay pain control [8, 11]. In a study conducted by Capogna et al. none of their patients requested manual RB. However, patients received PCEA as needed, and the number of patients requiring PCEA boluses was almost six times greater in the CEI group [12]. This means that although pain control was similar in both groups, patients under CEI needed more drugs in order to achieve the same VAS than the PIEB group.

Chua and Sia’s records of SBP from their patients were similar between the two groups [13]. They considered the low anesthetic concentration used and rate of epidural infusion applied to be responsible for this result. Likewise, we found similar hemodynamics in both groups. Although we used bupivacaine instead of ropivacaine, the drug concentration used was the same. This supports their results on the lack of impact of local anesthetics on patient hemodynamics when administering low epidural concentrations.

Side effects include those related to drugs used in epidural analgesia. In a study published last year by Maggiore, more patients in the CEI group had at least one narcotic-related adverse effect such as nausea, while the incidence of epidural-related side effects was similar in both groups [14]. They did not report mean time to occurrence of side effects. We found no difference concerning nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and hypotension. However, as evidenced in Table 6, mean post-epidural time to nausea was within the first hour for PIEB, while mean post-epidural time to nausea for CEI was 163 min. Since the first PIEB was administered 1 h after epidural block, we cannot conclude that nausea was related to the PIEB technique in our study.

Neuraxial administration of opioids, for instance fentanyl, has been associated to a risk of clinically significant diminished neonatal outcome [15]. Although Apgar has been questioned to not show accurate neonatal respiratory depression, it is the widely and routinely test used for this purpose [16]. We found no difference in Apgar scores at 1, 5, and 10 min after birth. These findings are consistent with literature evaluating the safety of analgesic techniques on neonates [3, 17, 18].

A study conducted by Salim et al. used a similar mixture of epidural solution to ours, but the local anesthetic concentration used per group was different [19]. Their study, as well as our study, found no difference with respect to the duration of labor and labor type.

In 2002, Hogan observed the macroscopic aspects of epidural spread discovering an uneven distribution of the solution in the epidural space depending on the pressures of compression applied [20]. Some previous studies were limited to manual boluses with the bias of applying different pressures by being operator-dependent [14, 21, 22]. Our study abolished this bias using automated boluses with default pressures of compression.

Even if the rate of unilateral motor block in our study was high, previous studies have described similar rates for this event [23, 24]. Differences between both groups for this variable were not statistically significant, evidencing that both techniques pose risk for unilateral motor block. However, epidural catheter was carefully placed 7 cm deep in all patients.

This study had some limitations: Our hospital is a private institution with a high income population and since sociocultural status has been linked to pain acceptance and different coping styles, further research including a broader population regarding economic level is advised. Another limitation was the difficulty in keeping an adequately statistical population size as labor progressed due to the nature of the study.

Finally, we conclude that, in line with previous studies, PIEB and CEI are effective analgesic techniques to control pain with similar success rates. However, in order to achieve the same results, a greater consumption of drug is required when administering CEI. No differences were seen on labor analgesia, and obstetric and newborn outcomes between both groups.

References

Jung H, Kwak KH (2013) Neuraxial analgesia: a review of its effects on the outcome and duration of labor. Korean J Anesthesiol 65:379–384

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (2002) ACOG practice bulletin: obstetric analgesia and anesthesia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 78:321–335

Yu-Nan L, Fei Z, Qiang L, Rui-Min Y, Jing-Chen L (2015) The value of programmed intermittent epidural bolus in labor analgesia. J Anesth Crit Care Open Access 2:00074

Hawkins JL (2010) Epidural analgesia for labor and delivery. N Engl J Med 362:1503–1510

Hawkins JL, Arens JF, Bucklin BA, Connis RT, Dailey PA, Gambling DR et al (2007) Practice Guidelines for Obstetric Anesthesia: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on obstetric anesthesia. Anesthesiology 106:843–863

Ramin SM, Gambling DR, Lucas MJ, Sharma SK, Sidawi JE, Leveno KJ (1995) Randomized trial of epidural versus intravenous analgesia during labor. Obstet Gynecol 86:783–789

George RB, Allen TK, Habib AS (2013) Intermittent epidural bolus compared with continuous epidural infusions for labor analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 116:133–144

McKenzie CP, Cobb B, Riley ET, Carvalho B (2016) Programmed intermittent epidural boluses for maintenance of labor analgesia: an impact study. Int J Obstet Anesth 26:32–38

Wong CA, Ratliff JT, Sullivan JT, Scavone BM, Toledo P, McCarthy RJ (2006) A randomized comparison of programmed intermittent epidural bolus with continuous epidural infusion for labor analgesia. Anesth Analg 102:904–909

Angle P, Charles C, Halpern S, Kung R, Kronberg J, Landy CK et al (2010) Phase 1 development of an index to measure the quality of neuraxial labour analgesia: exploring the perspectives of childbearing women. Can J Anaesth 57:468–478

Lim Y, Sia AT, Ocampo C (2005) Automated regular boluses for epidural analgesia: a comparison with continuous infusion. Int J Obstet Anesth 14:305–309

Capogna G, Camorcia M, Stirparo S, Farcomeni A (2011) Programmed intermittent epidural bolus versus continuous epidural infusion for labor analgesia: the effects on maternal motor function and labor outcome. A randomized double-blind study in nulliparous women. Anesth Analg 113:826–831

Chua SM, Sia AT (2004) Automated intermittent epidural boluses improve analgesia induced by intrathecal fentanyl during labour. Can J Anaesth 51:581–585

Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Silanos R, Carlevaro S, Gratarola A, Venturini PL, Ferrero S et al (2016) Programmed intermittent epidural bolus versus continuous epidural infusion for pain relief during termination of pregnancy: a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial. Int J Obstet Anesth 25:37–44

Carvalho B (2008) Respiratory depression after neuraxial opioids in the obstetric setting. Anesth Analg 107:956–961

González Cárdenas VH (2012) Depresión respiratoria neonatal y fentanilo intratecal. Rev Colomb Anestesiol 40:100–105

Bodner-Adler B, Bodner K, Kimberger O, Wagenbichler P, Kaider A, Husslein P et al (2003) The effect of epidural analgesia on obstetric lacerations and neonatal outcome during spontaneous vaginal delivery. Arch Gynecol Obstet 267:130–133

Gizzo S, Noventa M, Fagherazzi S, Lamparelli L, Ancona E, Di Gangi S et al (2014) Update on best available options in obstetrics anaesthesia: perinatal outcomes, side effects and maternal satisfaction. Fifteen years systematic literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet 290:21–34

Salim R, Nachum Z, Moscovici R, Lavee M, Shalev E (2005) Continuous compared with intermittent epidural infusion on progress of labor and patient satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol 106:301–306

Hogan Q (2002) Distribution of solution in the epidural space: examination by cryomicrotome section. Reg Anesth Pain Med 27:150–156

Leo S, Ocampo CE, Lim Y, Sia AT (2010) A randomized comparison of automated intermittent mandatory boluses with a basal infusion in combination with patient-controlled epidural analgesia for labor and delivery. Int J Obstet Anesth 19:357–364

Van der Vyver M, Halpern S, Joseph G (2002) Patient-controlled epidural analgesia versus continuous infusion for labour analgesia: a meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 89:459–465

Heesen M, Van de Velde M, Klöhr S, Lehberger J, Rossaint R, Straube S (2014) Meta-analysis of the success of block following combined spinal-epidural vs epidural analgesia during labour. Anaesthesia 69:64–71

Thomas JA, Pan PH, Harris LC, Owen MD, D’Angelo R (2005) Dural puncture with a 27-gauge Whitacre needle as part of a combined spinal-epidural technique does not improve labor epidural catheter function. Anesthesiology 103:1046–1051

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LE Ferrer: Project development, data analysis, manuscript editing. DJ Romero: Protocol development, data collection, manuscript writing. OI Vásquez: Protocol development, data collection, manuscript writing. EC Matute: Project development, data analysis, manuscript editing. M Van de Velde: Data analysis, manuscript editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Declaration of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferrer, L.E., Romero, D.J., Vásquez, O.I. et al. Effect of programmed intermittent epidural boluses and continuous epidural infusion on labor analgesia and obstetric outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet 296, 915–922 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4510-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4510-x