Abstract

Purpose

Wenjing decoction is a well-accepted traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea in East Asia, but its clinical effectiveness and risk have not been adequately assessed. In this paper, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of Wenjing decoction for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea.

Methods

Eight databases were used in our research: the Cochrane Library, the Web of Science, PubMed, EMBASE, the Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), the Chinese Scientific Journal Database, and the Wan-fang Database. The following search terms were used: (Wenjing decoction OR Wenjing formula OR Wenjing tang) AND (primary dysmenorrhea OR dysmenorrhea OR painful menstruation) AND (randomized controlled trial). No language limitation was used.

Results

A total of 18 studies, including 1736 patients, were included in the meta-analysis. Wenjing decoction was shown to be significantly better than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the improvement of primary dysmenorrhea according to the clinical effective rate (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.24–1.61), the visual analogue scale (MD −1.77, 95% CI −2.69 to −0.84), and the pain scale for dysmenorrhea (MD −1.81, 95% CI −2.41 to −1.22).

Conclusions

The results supported the clinical use of Wenjing decoction for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. However, the quality of the evidence for this finding was low due to a high risk of bias in the included studies. Therefore, well-designed randomized controlled trials are still needed to further evaluate the efficacy of Wenjing decoction for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Primary dysmenorrhea describes the lower abdominal pain that is experienced during menstruation in young females without pelvic pathology [1]. Approximately 60–88% of young females reportedly suffer from primary dysmenorrhea [2,3,4], which has a significant impact on women’s lives [5]. The initiation of primary dysmenorrhea has been reported to be primarily related to prostaglandin F2alpha (PGF2α), oxytocin, and vasopressin [6]. The production and release of PGF2α in women with primary dysmenorrhea may be significantly elevated, causing the uterine musculature to contract and subsequently resulting in pain. The main pharmacological therapies for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea have focused on alleviating menstrual pain and restoring exercise performance with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or oral contraceptives [7]. However, the continuous use of NSAIDs and oral contraceptives was reported to be associated with side effects such as gastrointestinal discomfort or injures to the mucosa [8, 9]. The side effects associated with such treatments have led patients to seek complementary and alternative medicines (CAM). For example, many physicians have used medicinal plants, such as Melissa officinalis [10], Fennel [11], or Bryophyllum pinnatum [12], for their antinociceptive effects. Acupuncture, traditional Chinese medicine [13], and anthroposophical medicine are all commonly used as CAM for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea.

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is well-accepted in countries such as China, Japan, and Korea [14,15,16]. The commonly used herbal formulas for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea include Danggui Shaoyao San, Shaofu Zhuyu decoction, and Wenjing decoction. Different herbal formulas are prescribed by physicians for different patients according to a patient’s symptoms. For example, if blood clots are observed during menstruation, physicians prefer to use Shaofu Zhuyu decoction to treat primary dysmenorrhea. If cold is felt in the lower abdomen, Wenjing decoction is preferred. When primary dysmenorrhea is accompanied by gastrointestinal discomfort, Danggui Shaoyao San is prescribed. Several systematic reviews of TCM for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea have been conducted. Lee et al. [17] conducted a systematic review to evaluate the efficacy of Danggui Shaoyao San for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea and concluded on the superiority of Danggui Shaoyao San over analgesics or placebo. Zhu et al. [18] conducted a review to determine the efficacy and safety of TCM for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. This review included a total of 3475 women and TCM showed an obvious advantage for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea compared with placebo, no treatment, and other treatment. Lee et al. [19] conducted a systematic review to evaluate the TCM Shaofu Zhuyu decoction for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea, and the meta-analysis results showed the superiority of Shaofu Zhuyu decoction compared with NSAIDs. However, no relevant systematic reviews have assessed the clinical effectiveness or the risk of Wenjing decoction in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea.

Wenjing decoction is an ancient traditional Chinese medicine formula that originated from the book Synopsis of Golden Chamber, which was written by Zhongjing Zhang (approximately A.D. 150–219) during the eastern Han dynasty in China. The Wenjing decoction consists of the following 12 herbs: Tetradium ruticarpum, Ophiopogon japonicas, Angelica sinensis, Paeonia lactiflora pallv, Ligusticum Chuanxiong Hort, Panax Ginseng, Cinnamomum cassia Presl, Donkey-Hide Gelatin, Cortex Moutan, Ginger, Liquorice, and Pinellia ternata. The main components of these herbs have therapeutic effects on primary dysmenorrhea. For example, the evodiamine in Tetradium ruticarpum has been recommended for abdominal pain and dysmenorrhea [20]. Angelica sinensis has active components such as ferulic acid, which shows an inhibitory effect on uterine movement [21]. Cinnamic acid and cinnamic aldehyde in Cinnamomum cassia Presl inhibit uterine contractions by reducing the PGF2α level and intracellular Ca++ to suppress cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and oxytocin receptor (OTR) expression [22].

Considering the combined action of the different herbs in Wenjing decoction, Hsu et al. [23] extracted the active ingredients of Wenjing decoction using a 50% alcohol solution to analyze its physiological mechanism on uterine contractility in vitro. The antagonism of PGF2α and acetylcholine (ACh) was shown to be the major mechanism for Wenjing decoction in the treatment of dysmenorrhea. Wenjing decoction also stabilizes the membrane potential of uterine smooth muscle cells and subsequently decreases uterine contractions by decreasing the membrane action potential. Focusing on oxytocin as a tool to investigate Ca++ flow, Wenjing decoction demonstrates a significant linear and dose dependent relationship in its inhibitory effects on the uterine contractions, not only in the suppression of the influx of Ca++ ions but also in the suppression of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca++ ions release. Both Ca++ ions and SR Ca++ ions play a role in the induction of uterine contractions. This effect can be considered an auxiliary mechanism of the Wenjing decoction in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea.

Many clinical trials have reported the beneficial effects of Wenjing decoction in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Considering no relevant systematic reviews have assessed the clinical effectiveness or the risk of Wenjing decoction, in this study, a meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of Wenjing decoction for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea.

Methods

The protocol of this study was registered in PROSPERO with the registration number CRD42017054385.

Database and search strategies

We searched the following electronic databases: the Cochrane Library, the Web of Science, PubMed, EMBASE, the Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), the Chinese Scientific Journal Database, and the Wan-fang Database up to December 31, 2016. The following search terms were used: (Wenjing decoction OR Wenjing formula OR Wenjing tang) AND (primary dysmenorrhea OR dysmenorrhea OR painful menstruation) AND (randomized controlled trial). No language limitation was used.

Inclusion criteria

The included studies must be randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Trials with diagnoses of primary dysmenorrhea were chosen. Primary dysmenorrhea occurs in women of reproductive age during menses and manifests as lower abdomen pain. Pelvic examination, ultrasound scan, or laparoscopy can be used to check the existence of other diseases such as endometriosis when primary dysmenorrhea occurs. Trials that were identified as pelvic pathology were excluded. Interventions using Wenjing decoction or modified Wenjing decoction alone were chosen. Modified Wenjing decoction, with a similar efficacy to Wenjing decoction, was prescribed by TCM physicians according to the patient’s clinical symptoms. The control groups used NSAIDs for pain relief. The primary outcome was the clinical effective rate.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria in the meta-analysis included (a) non-RCTs, case studies, qualitative studies, experience summaries, and animal experiments; (b) unpublished or repeated literature; (c) studies that did not use Wenjing decoction as the main intervention or used Wenjing decoction in combination with other treatments such as acupuncture; and (d) patients with a diagnosis of pregnancy, stroke, some other serious organic diseases, or with a severe drug allergic medical history.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Four reviewers (Gao, Jia, Zhang, and Ma) independently performed the data extraction and the quality assessments. The statistical analysis was conducted using RevMan 5.3 software (provided by the Cochrane Collaboration), and the risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane tool, which includes the following seven criteria: (1) random sequence generation, (2) allocation concealment, (3) blinding of the patients and personnel, (4) blinding of the outcome assessment, (5) incomplete outcome data, (6) selective outcome reporting, and (7) other sources of bias. Quality was classified into three categories: low risk of bias, high risk of bias, and unclear risk of bias. Any disagreement was resolved by discussions between all reviewers.

Results

Description of the included studies

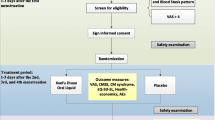

In this review, 722 potentially eligible studies were identified, but 648 were excluded: 128 repeated publications and 520 irrelevant studies. The full texts of 74 articles were assessed and 56 studies were excluded, including 26 studies that used a combination with other treatments, 24 animal experiments, 5 unpublished articles, and 1 that did not use NSAIDs as the control group. Finally, a total of 18 studies [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], including 1736 patients, were included in the meta-analysis and were all published in Chinese Journal Literature Databases. The screening process is summarized in a flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Details of the 18 studies are summarized in Table 1. The intervention group included 891 patients and the control group included 845 patients. Disease courses of the patients were from 3 months to 16 years, and treatment period lasted from three to six menstruation cycles. In the intervention group, Wenjing decoction alone was used to treat primary dysmenorrhea, and compositions of the formulas in the included studies are shown in “Appendix”. In the control group, all the studies used NSAIDs, including seven studies [25, 26, 28, 30, 31, 34, 35] used ibuprofen, five studies [24, 27, 29, 36, 39] used fenbid, four studies [32, 33, 38, 41] used indomethacin, one study [37] used paracetamol and codeine, and one study [40] used loxoprofen sodium.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias was high in the included studies (Fig. 2). All the studies were described using randomization, but only six [27, 28, 31, 33, 35, 38] of these studies reported using an appropriate method of random sequence generation and two [40, 41] of these studies reported using inappropriate methods of clinic record number. None of the studies described the method for allocation concealment or the blinding of the outcome assessment, except that one study [40] used clinic record number for allocation concealment. Most of the included studies had a high risk of performance bias because both the physicians and the patients clearly knew which treatment was being given.

Outcome measurements

The outcome measurements of the included studies include clinical effective rate, pain scale, visual analogue scale, and adverse events.

Clinical effective rate

The criteria for clinical effective rate are as follows: cure (abdominal pain completely disappeared during menstruation, and no recurrence was observed after stopping the medication), significant effective (a significant improvement in abdominal pain during menstruation, with occasional recurrence after stopping the medication), effective (improvement in abdominal pain during menstruation, with recurrence after stopping the medication), and no effect (no improvement in abdominal pain during menstruation). The clinical effective rate is the accumulation of cure rate, significant effective rate, and effective rate. All the studies showed that Wenjing decoction has a higher clinical effective rate compared with NSAIDs. Since high heterogeneity was observed in the meta-analysis (I 2 = 85%, which is higher than 50%), a model of random effects was used to calculate the pooled estimation with an analysis of the dichotomous data using relative risk (RR), including 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The total meta-analysis showed favorable effects of Wenjing decoction on clinical effective rate (n = 1736, RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.24–1.61, P < 0.01) compared with the control group (Fig. 3). A subgroup analysis was also performed between different NSAIDs. The results showed significant heterogeneity in the subgroup fenbid, with I 2 = 94%, P = 0.02.

Pain scale

Two types of pain scales were used in the included studies, including two studies [28, 35] used visual analogue scale (VAS), and three studies [26, 38, 39] used pain scale for dysmenorrhea, which was issued by Ministry of Health in China. The other studies did not mention a pain scale. Mean difference (MD) was used for analysis of continuous data on pain scales.

The meta-analysis of group that used VAS pain scale shows a MD of −1.77 (95% CI −2.69 to −0.84) with high heterogeneity (I 2 = 85%), as shown in Fig. 4, which means that the patients who used Wenjing decoction had significantly lower VAS scales than those who used NSAIDs. Meta-analysis of the group that used pain scale for dysmenorrhea shows a MD of −1.81 (95% CI −2.41 to −1.22) with low heterogeneity (I 2 = 0%), as shown in Fig. 5, indicating that Wenjing decoction can significantly decrease pain scale for dysmenorrhea compared to NSAIDs.

Adverse events (AEs)

One study [38] reported AEs of hypermenorrhea in the intervention group, and four studies [24, 29, 31, 38] reported AEs in the control group, including diarrhea, skin rash, and nausea. Diarrhea is identified by having at least three liquid bowel movements each day. Skin rash refers to a change in the skin in its color, appearance, or texture. Nausea refers to discomfort in the upper stomach that induces an involuntary urge to vomit. Other studies did not report AEs.

Heterogeneity analysis

A heterogeneity plot for the included studies is shown in Fig. 6. In this figure, the z statistic is plotted against the reciprocal standard error for each study. A line passing through the origin is used to fit on the data, and the slope of the line is the overall log odds ratio in the fixed effect meta-analysis. Confidence bounds are positioned at two units over and below the regression line with a 95% confidence interval. All the points are expected to lie within the confidence bounds in the absence of heterogeneity. High heterogeneity was observed in the study by Zeng et al. [36], while other studies showed low heterogeneity.

A forest plot of the clinical effective rate after removing the study by Zeng et al. [36] is shown in Fig. 7. The heterogeneity for subgroup Fenbid was shown to be decreased from 94 to 0%, and the heterogeneity for all the studies decreased from 85 to 58%. The meta-analysis also shows favorable effects of Wenjing decoction on the clinical effective rate (n = 1480, RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.21–1.42, P < 0.01) compared with the control group.

Discussion

Currently, NSAIDs are the main pharmacological therapies for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea because they alleviate menstrual pain and restore exercise performance. However, inadequate pain control and associated adverse events lead patients to seek complementary alternative medicines. Traditional Chinese medicines, such as Wenjing decoction, have been widely utilized by TCM physicians to treat primary dysmenorrhea. However, the effectiveness of Wenjing decoction has been controversial because of a lack of systematic reviews to assess the existing evidence. Therefore, the goal of this review was to assess the effects of Wenjing decoction in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea.

A total of 18 studies with 1736 patients with a comparison between Wenjing decoction and NSAIDs in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea were included in this review. Results of the meta-analysis suggest that Wenjing decoction is superior to NSAIDs for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea in terms of clinical effective rate (RR 1.41, 95% CI 1.24–1.61), VAS scale (MD −1.77, 95% CI −2.69 to −0.84), and pain scale for dysmenorrhea (MD −1.81, 95% CI −2.41 to −1.22). However, the results were mainly based on short-term effectiveness, and only one study reported long-term effectiveness with pain scale for dysmenorrhea after three menstrual cycles with treatment (MD −5.70, 95% CI −6.53 to −4.87).

High heterogeneity was found in this meta-analysis, with clinical effective rate of I 2 = 85%, and VAS pain scale of I 2 = 85%. The reasons for this may be that modified Wenjing decoction was used in every included study, making the effect of Wenjing decoction difficult to be assessed. Additionally, different NSAIDs were used in different control groups. A heterogeneity analysis for the included studies was conducted. The study by Zeng et al. [36] was shown to have high heterogeneity, while other studies showed low heterogeneity. A meta-analysis of the clinical effective rate after removing the study by Zeng (2015) was conducted. The heterogeneity for subgroup Fenbid decreased from 94 to 0%, and the heterogeneity for all the studies decreased from 85 to 58%. The meta-analysis also showed favorable effects of Wenjing decoction according to the clinical effective rate (n = 1480, RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.21–1.42, P < 0.01) compared with the control group.

The methodological quality for this finding was relatively low because of the high risk of bias. There are several limitations in this systematic review. First, for most of the included studies, the methods for randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding were not reported clearly. Due to the characteristics of TCM, both the physicians and the patients clearly knew which treatment was being given, creating a high risk for bias in the blinding methods. Second, in the 18 included studies, only 6 studies had sample sizes greater than 100 trials, and the small sample sizes in most studies made meaningful conclusions difficult to be drawn. Third, clinical effective rate was the main outcome measurement for most studies, but a bias from the physicians may decrease the reliability and validity of the studies. Fourth, all the studies were conducted in China, which may limit the generalization of the findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this meta-analysis included 18 studies that used TCM Wenjing decoction for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea, and the results supported the clinical use of Wenjing decoction. However, the studies analyzed to date are of relatively low quality. More rigorous RCTs with large sample sizes and consideration of long-term effects are recommended to further evaluate the clinical efficacy and the adverse effects of Wenjing decoction in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea.

References

Osayande AS, Mehulic S (2014) Diagnosis and initial management of dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician 89(5):341–346

Kural M, Noor NN, Pandit D, Joshi T, Patil A (2014) Menstrual characteristics and prevalence of dysmenorrhea in college going girls. J Fam Med Prim Care 4(3):426–431

Polat A, Celik H, Gurates B, Kaya D, Nalbant M, Kavak E, Hanay F (2009) Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea in young adult female university students. Arch Gynecol Obstet 279(4):527–532

Aksoy AN, Laloglu E, Ozkaya AL, Yilmaz EP (2017) Serum heme oxygenase-1 levels in patients with primary dysmenorrhea. Arch Gynecol Obstet 295(4):929–934

Celik H, Gurates B, Parmaksiz C, Polat A, Hanay F, Kavak B, Yavuz A, Artas ZD (2009) Severity of pain and circadian changes in uterine artery blood flow in primary dysmenorrhea. Arch Gynecol Obstet 280(4):589–592

Akerlund M (1993) The role of oxytocin and vasopressin in the initiation of preterm and term labour as well as primary dysmenorrhoea. Regul Pept 45(1–2):187–191

Chantler I, Mitchell D, Fuller A (2009) Diclofenac potassium attenuates dysmenorrhea and restores exercise performance in women with primary dysmenorrhea. J Pain 10(2):191–200

Hee L, Kettner LO, Vejtorp M (2013) Continuous use of oral contraceptives: an overview of effects and side-effects. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 92(2):125–136

Sostres C, Gargallo CJ, Arroyo MT, Lanas A (2010) Adverse effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, aspirin and coxibs) on upper gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 24(2):121–132

Kalvandi R, Alimohammadi S, Pashmakian Z, Rajabi M (2014) The effects of medicinal plants of melissa officinalis and salvia officinalis on primary dysmenorrhea. Sci J Hamadan Univ Med Sci 21(2):105–111

Ghodsi Z, Asltoghiri M (2014) The effect of fennel on pain quality, symptoms, and menstrual duration in primary dysmenorrhea. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 27(5):283–286

Ojewole JA (2005) Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory and antidiabetic effects of Bryophyllum pinnatum (Crassulaceae) leaf aqueous extract. J Ethnopharmacol 99(1):13–19

Eisenhardt S, Fleckenstein J (2016) Traditional Chinese medicine valuably augments therapeutic options in the treatment of climacteric syndrome. Arch Gynecol Obstet 294(1):193–200

Chen HY, Lin YH, Su IH, Chen YC, Yang SH, Chen JL (2014) Investigation on Chinese herbal medicine for primary dysmenorrhea: Implication from a nationwide prescription database in Taiwan. Complement Ther Med 22(1):116–125

Yeh LL, Liu JY, Lin KS, Liu YS, Chiou JM, Liang KY, Tsai TF, Wang LH, Chen CT, Huang CY (2016) A randomised placebo-controlled trial of a traditional Chinese herbal formula in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea. PLoS One 2(8):e719

Qian Y, Xia XR, Ochin H, Huang C, Gao C, Gao L, Cui YG, Liu JY, Meng Y (2016) Therapeutic effect of acupuncture on the outcomes of in vitro fertilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 295(3):543–558

Lee HW, Jun JH, Kil K-J, Ko B-S, Lee CH, Lee MS (2016) Herbal medicine (Danggui Shaoyao San) for treating primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Maturitas 85:19–26

Zhu X, Proctor M, Bensoussan A, Wu E, Smith C (2008) Chinese herbal medicine for primary dysmenorrhea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD005288

Lee H, Choi TY, Myung CS, Lee JA, Lee MS (2016) Herbal medicine (Shaofu Zhuyu decoction) for treating primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Maturitas 86:64–73

Wu CL, Hung CR, Chang FY, Lin LC, Pau KY, Wang PS (2002) Effects of evodiamine on gastrointestinal motility in male rats. Eur J Pharmacol 457(2–3):169

Su S, Hua Y, Duan J, Zhou W, Shang E, Tang Y (2010) Inhibitory effects of active fraction and its main components of Shaofu Zhuyu decoction on uterus contraction. Am J Chin Med 38(4):777–787

Sun L, Liu L, Zong S, Wang Z, Zhou J, Xu Z, Ding G, Xiao W, Kou J (2016) Traditional Chinese medicine Guizhi Fuling capsule used for therapy of dysmenorrhea via attenuating uterus contraction. J Ethnopharmacol 191:273–279

Hsu CS, Yang JK, Yang LL (2003) Effect of a dysmenorrhea Chinese medicinal prescription on uterus contractility in vitro. Phytother Res 17(7):778

Chen H, Luo Q (2014) Clinical observation on treating primary dysmenorrhea with modified Wenjing decoction. China Health Care Nutr 5:3405–3406

Chen X (2016) Efficacy observation on treating 60 cases of primary dysmenorrhea with modified Wenjing decoction. For All Health 06:51–52

Feng J (2012) Clinical observation on treating 30 cases of primary dysmenorrhea with the Wenjing decoction. Hunan J Tradit Chin Med 28(5):53–54

Gao Q (2014) Efficacy observation on treating primary dysmenorrhea with modified Wenjing decoction. Med Forum 23:3127–3128

Jiang Y (2015) Clinical observation on treating primary dysmenorrhea with modified Wenjing decoction. Strait Pharm J 27(5):215–216

Lei Y, Yu X (2013) Clinical observation on treating primary dysmenorrhea with modified Wenjing decoction. China Health Care Nutr 23(2):970–971

Liu Y, Wang J, Zhao J, Li H (2015) Clinical efficacy observation on treating primary dysmenorrhea of congealing cold and blood stasis with modified Wenjing decoction. Heilongjiang J Tradit Chin Med 3:46–47

Lu Y (2015) Clinical observation on treating primary dysmenorrhea with Wenjing decoction. Diet Health 2(15):170–171

Mei H (2014) Clinical observation on treating primary dysmenorrhea of congealing cold and blood stasis with Wenjing decoction. Guangxi J Tradit Chin Med 37(4):26–27

Tang Z, Liu Y (2015) Clinical observation on treating 80 cases of primary dysmenorrhea with the Wenjing decoction. Clin J Chin Med 31:95–97

Wang N (2016) Clinical analysis on treating primary dysmenorrhea of congealing cold and blood stasis with modified Wenjing decoction. China Health Stand Manag 07:137–138

Wu Q (2015) 51 cases of treating primary dysmenorrhea with Wenjing decoction. China’s Naturop 23(11):31–32

Zeng G, Min G, Liu X (2015) Clinical observation on treating primary dysmenorrhea with modified Wenjing decoction. J New Chin Med 47(3):171–172

Zhang J, Li Y (2015) Clinical observation on treating 140 cases of primary dysmenorrhea of congealing cold and blood stasis with modified Wenjing decoction. Gansu Sci Technol 12:96–97

Zhang T (2014) Clinical efficacy observation on treating primary dysmenorrhea with Wenjing decoction in Synopsis of Golden Chamber. Nei Mongol J Tradit Chin Med 26:34–35

Zhao S (2014) Clinical observation on treating primary dysmenorrhea of congealing cold and blood stasis with modified Wenjing decoction. China Health Care Nutr 24(03):1704

Zhao W, Wan Q, Yang Y (2016) Clinical observation on treating primary dysmenorrhea of congealing cold and blood stasis with Wenjing decoction. Compr Med 15:97

Zheng Y, Zhao H, Zhou Z (2008) Clinical observation on treating 42 cases of primary dysmenorrhea of congealing cold and blood stasis with modified Wenjing decoction. Contemp Med 11:63–64

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LG: Data collection and management, data analysis, manuscript writing. CJ: Protocol development, data analysis, manuscript writing. HZ: Data collection and management, data analysis, manuscript writing. CM: Data analysis, manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81373770).

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, L., Jia, C., Zhang, H. et al. Wenjing decoction (herbal medicine) for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 296, 679–689 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4485-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4485-7