Abstract

Introduction

Japan is a super-aging society, the geriatric care system establishment for hip fractures is at an urgent task. This report described our concept of multidisciplinary care model for geriatric hip fractures and 5-year outcomes at the Toyama City Hospital, Japan.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, a multidisciplinary treatment approach was applied for elderly patients with hip fracture since 2014. These patients (n = 678, males: n = 143, mean age: 84.6 ± 7.5 years), were treated per the multidisciplinary care model. Time to surgery, length of hospital stays, complications, osteoporosis treatment, mortality, and medical costs were evaluated.

Results

The mean time to surgery was 1.7 days. Overall, 78.0% patients underwent surgery within 2 days. The mean duration of hospital stay was 21.0 ± 12.4 days. The most frequent complication was deep venous thrombosis (19.0%) followed by dysuria (14.5%). Severe complications were pneumonia 3.4%, heart failure 0.8% and pulmonary embolism 0.4%. The in-hospital mortality rate was 1.2%. The 90-day, 6-month, and 1-year mortality rates were 2.5%, 6.7%, and 12.6%, respectively. The pharmacotherapy rate for osteoporosis at discharge was 90.7%, and the continuation pharmacotherapy rate was 84.7% at 1-year follow-up. The total hospitalization medical cost per person was lower than about 400 other hospitals’ average costs every year, totaled 14% less during the 5-year study period.

Conclusion

We have organized a multidisciplinary team approach for geriatric hip fracture. This approach resulted in a shorter time to surgery and hospital stay than the national average. The incidence of severe complications and mortality was low. The multidisciplinary treatment has maintained a high rate of osteoporosis treatment after discharge and at follow-up. Furthermore, the total medical cost per person was less than the national average. Thus, the multidisciplinary treatment approach for geriatric hip fractures was effective and feasible to conduct in Japan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Japan has the second-highest life expectancy in the world and has an increasing number of elderly patients with hip fractures due to the rapid expansion in the proportion of the elderly [1]. The estimated total number of new patients with hip fracture in 2012 in Japan was 175,700 [2], but it has been estimated that the number of new patients with hip fractures per year would be ~ 320,000 by 2040 [3]. Therefore, the economic and social burden of hip fractures on the health care system is expected to increase dramatically. The difficult part of treating hip fractures in the elderly is not only the fracture itself but rather various aspects, such as perioperative care, postoperative management, rehabilitation, nursing, fall preventive measures and osteoporosis treatment that would result in a decrease of secondary fracture. Thus, many models of care have been developed, which have shown improvement in patient care and outcomes [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12], but most of these models are in collaboration with geriatricians. However, it was necessary to establish a care model that could be introduced into Japanese hospitals, where geriatricians are rare under the current situation. The objective of this study was to describe our multidisciplinary care model for geriatric hip fractures and present 5-year outcomes. Our multidisciplinary care model, namely, the “Toyama model,” is a method of care that provides active treatment via collaboration among Orthopedic surgery, Internal medicine, and all other disciplines involved in hip fracture treatment. We have organized a multidisciplinary team for geriatric hip fracture in 2013. After one year of preparation, we started an intervention program based on in-hospital treatment both before surgery and shortly afterward was established and applied in caring of the elderly patients with hip fractures from 2014. The in-hospital intervention comprised medical and physical assessments, early surgery, osteoporosis treatment, pain management, nutrition management, fall prevention, and early discharge planning.

Methods

Patients

We conducted a multidisciplinary treatment approach study with elderly patients from January 2014 to December 2018 who were admitted to our Orthopedic department with hip fractures. Patients’ inclusion criteria were hip fracture, aged 65 years and older, and treated in accordance with the multidisciplinary treatment approach. Patients’ exclusion criteria were as follows: patients treated conservatively with no operation, those with pathological hip fractures, those with multiple injuries or caused by high-energy trauma, and those caused by fall during hospitalization were excluded.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by our institutional review board (approval # 2018–19), and all of its activities were carried out in compliance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration, updated in 2008. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Extraction of patients’ demographic and clinical data

Data were obtained from medical records of the patients admitted to our hospital and included in the study from January 2014 to December 2018. Data for the patients’ demographics and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1 including age, gender, cognitive disorder, comorbidity, previous osteoporotic hip fracture on the other side, prefracture living, type of fracture, surgical procedure. The following parameters were evaluated: (1) Time to surgery (time from arrival at the hospital to the start of surgery); (2) length of hospital stay (days from admission to the day of discharge); (3) postoperative complications; (4) osteoporosis treatment (prescription of anti-osteoporosis medication at admission, at discharge and 1-year follow-up); and (5) mortality (in-hospital, 90-day, 6-month, and 1-year).

Mortality data were obtained by accessing the hospital’s electronic data system and a survey conducted through the mail. Additionally, average medical costs were compared with other hospitals that had adopted a comprehensive payment system based on “Diagnosis Procedure Combination” each year. Only the data on patients with hip fracture aged > 65 years who underwent surgery were extracted.

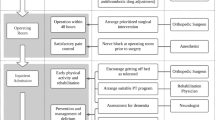

Our Toyama model

The multidisciplinary approach included the involvement of orthopedic surgeons, internists, anesthesiologists, psychiatrists, urologists (from 2015), geriatrician (from 2017), nurses, physical therapists, ward pharmacists, medical social workers, registered dietitians, radiological technologists, medical technologists, ambulatory services, and administrative staff.

The following three features were the fundamental pillars of our multidisciplinary approach:

To decrease time to surgery safely and smoothly

Medical examination for each patient was performed by an internist on admission: Preoperative assessment was undertaken in the Emergency Department by an internist immediately before admission. To reduce the burden on primary care internists, consultation criteria were created by which patients were referred to specialists such as a cardiologist, pulmonologist, nephrologist, endocrinologist, or other specialists (Table 2).

United chart: In routine medical care, the medical record is updated by each department (physician medical records, nursing records, and others). The same patient information is often described in duplicate, resulting in a reduction in the efficiency of the practice. Thereby, we developed an electronic united chart that allowed all staff to record and understand patient information more easily and accessible by all related discipline (Fig. 1). It consists of three sheets and contains the minimum preoperative patient information required. It decreased the time taken for each department to receive information on the patient and improved the efficiency of medical care.

Guidelines and Manual: Interdisciplinary and inter-professional guidelines were developed for the following parameters: organizational structure, preoperative assessment, the timing of surgery, antibiotic treatment, anti-thromboembolic treatment, workflow, protocol for the cases of preexisting anticoagulation therapy, pain therapy, prevention and treatment of delirium, evaluation and treatment of osteoporosis, and nutritional management.

To reduce perioperative complications

We tried to reduce perioperative psychiatric complications by adopting prevention and prompt treatment of delirium in cooperation with the psychiatrist. Furthermore, in 2015, we made a cooperative care algorithm for dysuria with urologists, and in 2017, we started perioperative comanagement with geriatricians. Although the geriatricians did not work full-time, they work part-time 2–3 days/week exclusively in the orthopedic ward. Regarding our mobilization protocol, after the surgery, sitting and standing training was started on the day after the surgery, and walking practice with full weight bearing started from the second day.

To prevent secondary fracture

Regarding the osteoporosis treatment, the ward pharmacist checked the anti-osteoporosis medication prescription. Moreover, geriatricians and ward pharmacists worked together to tackle polypharmacy measures. Additionally, we performed evaluations of nutritional status at hospitalization with the help of dieticians. During hospitalization, dietitian provided with nutritional guidance and strive to improve the nutritional status of each patients. Rehabilitation intervention began from the day after surgery while controlling pain, leaving the bed, and starting walking exercise on the second day. Pharmacists, dietitians, physiotherapists, and nurses started to educate patients and family members about the prevention of secondary fracture by making use of each specialty. Regarding fall prevention, the ward pharmacist reviewed patients' medications for side effects and interactions that may increase the risk of falling. Physical therapists taught an exercise program aimed at improving balance, flexibility, muscle strength and gait. Nurses instructed patients on what should be improved in the living environment that is prone to fall.

Besides, since 2016, we have established Fracture Liaison Service (FLS) on the ward and after a patient’s discharge to continue osteoporosis management. On the ward, we have pharmacists who cooperate with the physicians regarding patients’ medication needs, and even after a patient’s discharge. Additionally, dedicated healthcare coordinators contact patients by telephone regularly after discharge to check the continuation of anti-osteoporosis pharmacotherapy, walking ability and re-fall event. And they give advice or to instruct the patient to visit the hospital if necessary.

Results

Initially, a total of 731 patients aged 65 years and older with hip fracture were admitted to the Toyama City Hospital from 2014 to 2018. We excluded 53 patients, treated conservatively with no operation, had pathological fractures, those with multiple injuries or caused by high-energy trauma, and those caused by fall during hospitalization. Therefore, 678 patients were enrolled and evaluated during a multidisciplinary treatment approach in the integrated care pathway (Fig. 2).

Data and entries of patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 84.6 ± 7.5 years (range 65–101 years) with a female predominance (78.9%). 51.9% of patients who had cognitive dysfunction. Co-morbidities were, 60.0% of patients had hypertension, 20.6% had diabetes, 30.2% had a cardiovascular disorder, 14.2% had a respiratory disease, and 13.2% had renal dysfunction. In addition, 9.7% of patients had a history of contralateral osteoporotic hip fractures. Regarding living conditions, before the injury, 69% of the patients lived in their own homes. The type of fracture was trochanteric fracture (63.7%) and neck fracture (36.3%).

Time to surgery and the total length of hospital stay

The average days from patient admission to surgery were 1.7 ± 2.2 days (range 0–24 days). 27.9% on the day, 31.1% the next day, 19.0% 2 days later, and overall, 78.0% had surgery within 2 days. In addition, these average days were 1.3 ± 2.3 days for patients who were admitted on weekdays and 2.2 ± 1.9 days for patients who were admitted on weekends and public holidays. The average duration of hospital stay was 21.0 ± 12.4 days (range 8–161 days; Table 3).

Complications

Table 4 summarizes the perioperative complications. The most frequent complication was deep venous thrombosis (19.0%), followed by dysuria (14.5%). Severe complications were pneumonia (3.4%), heart failure (0.8%), sepsis (0.7%), and pulmonary embolism (0.4%). The in-hospital mortality rate was 1.2%.

Osteoporosis medication treatments

The rate of patients who were on anti-osteoporosis pharmacotherapy before the injury was low at 21.2%. However, at the time of discharge, this rate was improved to 90.7% by multidisciplinary care (Table 3). Moreover, the continuation rate of pharmacotherapy continued to be as high as 84.7% at 1-year follow-up, thanks to the FLS.

Mortality

The data lacked three patients at 90-day, seven at 6-month, and 19 at 1-year. The 90-day, 6-month and 1-year mortality rates were 2.5% (n = 17), 6.7% (n = 45), and 12.6% (n = 83), respectively, with males having higher mortality rates than females (Table 5).

Medical costs

Data for domestic acute care hospital costs for about 400 hospitals/year were available, extracted and compared. The mean total hospitalization medical cost per patient at our hospital was lower (5 years overall mean = 14%) than the other hospitals’ mean cost for five consecutive years (2014–2018; Table 6).

Discussion

Our institution is the first to establish a multidisciplinary treatment approach for geriatric hip fracture in Japan, and this is the second report from our facility [13], which is a typical public hospital in a local city in Japan.

Surgical delay has been associated with an increased length of hospital stay and a higher risk of postoperative complications [14,15,16]. A meta-analysis found that a surgical delay of more than 48 h increased mortality rate [17]. In Japan, the national average of the preoperative waiting time after hip fracture tends to shorten year by year, but it was still 4.5 days in 2014 [18], which is very long, compared with other countries [19]. In this second report, the rate for patients who received surgery within 48 h was 67.6% which is lower than what we obtained for our first report 72.5%. Two patients who had a waiting time of more than 20 days were hemodialysis patients with sepsis from the time of admission (had surgery 23 days later), and another patient with obstructive jaundice (had surgery 24 days later). Except for possible patient-side issues, the most significant factor of delay in surgery was hospitalization related to weekends and public holidays (Table 3). It is still challenging to have a well-structured system for performing surgery on holidays at our facility with the current manpower. In that respect, it might still be necessary not only to consolidate fracture patients but also to integrate medical facilities such as trauma centers. However, after we achieved smooth cooperation between the departments, approximately 10% (66 cases) of patients were able to start surgery within 4 h after arrival on weekdays.

The lengths of the hospital stay for patients following hip fractures are often reported as an outcome measure. The average length of stay in an acute care hospital in Japan was 36.8 days in 2014 [18]; therefore, the hospital stay lengths in our hospital 21.0 ± 12.4 days (range 8–161 days) was short in Japan but it is still very long, compared to Western countries. We think that the difference in the medical insurance system has a significant influence; most patients or their families prefer inpatient treatment until activities of daily lives are restored to near preinjury level. Therefore, many patients continue treatment at convalescent facilities for more than one month, focusing on rehabilitation. But the current situation is that there are not enough facilities to accept these patients and they tend to stay longer in acute phase hospital.

The most common postoperative complication was deep venous thrombosis (19.0%), most of which were asymptomatic deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Pulmonary embolism (PE) occurred in three cases (0.4%); only one of three cases was symptomatic embolism. DVT was confirmed by ultrasonography, and PE was confirmed by contrast computerized tomography scan. Most national guidelines recommend the use of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis for patients undergoing surgery for hip fracture [20,21,22,23,24,25], but in principle, we do not use routine pharmacological prophylaxis, only mechanical prophylaxis. Our thromboprophylaxis protocol is mostly physical prophylaxis before and after surgery such as the use of graduated compression stocking and intermittent pneumatic compression or venous foot pump. Patients with an unknown injury date or those with a waiting period of 2 days or longer were evaluated by ultrasonography before surgery. After surgery, patients were evaluated by ultrasonography on day 7 under our screening criteria. While the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) consensus is widely adopted in Western countries, in Japan pharmacological thromboprophylaxis for hip fracture surgery varies among institutions and is not necessarily implemented routinely. In this case series, most DVT occurrences were asymptomatic distal DVTs (114/129), which followed the course without additional pharmacotherapy. Although pharmacological prophylaxis reduces the incidence of DVT [26, 27], its primary purpose is to prevent symptomatic PE, especially fatal PE. Our incidents of DVT were undoubtedly higher than that of patients receiving pharmacological prophylaxis, but the incidence of symptomatic PE was 0.1% (1/678) was similar to that of patients receiving pharmacological prophylaxis (0–0.25%) [26,27,28,29]. There is a report that pharmacological prophylaxis was more effective than mechanical methods at reducing the risk of DVT [30], but it might be necessary to validate the cost-effectiveness of routine pharmacological prophylaxis with current protocols.

Regarding dysuria, we had tried to remove the urinary catheter early in the postoperative period, but it still occurred in 14.5% of patients. Many of the patients, especially females, were associated with dysuria, such as the neuropathic bladder with aging. There is a report that 51.3% of patients admitted due to hip fracture suffered urinary retention, and this adversely affects functional recovery particularly in female patients [31]. Since 2015, urologists also participated in the multidisciplinary approach and jointly prepared and practiced a therapeutic algorithm for dysuria. Eventually, 76.5% of all patients who had experience dysuria improved at discharge (by intermittent catheterization only: 21.4%, intermittent catheterization, and drug therapy: 55.1%), but 23.5% did not. Thus, this complication should be recognized as a common adverse event for elderly patients. Establishment of monitoring plans for treatment is mandatory.

In a large study of patients with hip fractures, the incidence of pneumonia and heart failure are major postoperative complications, occurred in 9% of patients (245/2448) and 5% of patients (119/2,448), respectively [32]. Also, in integrated orthogeriatric care model studies, the incidence of pneumonia and heart failure ranged from 3.9–9.5 to 1.0–7.7%, respectively [5, 7,8,9,10]. Our outcomes for the incidence of pneumonia and heart failure were 3.4% and 0.8%, respectively, and were favorable compared to the integrated orthogeriatric care models.

Similarly, our in-hospital mortality rate (1.2%) was higher than that (0.6%) reported by Vidan et al. [5], but was lower than that reported by the others [7,8,9, 11, 12]. Also, our 1-year mortality rate (12.6%) was higher than that (11.2%) reported by Leung and colleagues [8] but was lower than most other studies. The exact reason for the low one-year mortality rate cannot be identified, but it may be related to the longer hospital stays in Japan compared to other countries. However, in our data, there was no significant difference in statistical analysis between 1-year mortality and length of stay. Regarding the mortality rate by gender of elderly hip fracture patients, as previously reported, the mortality rate for men was higher than that for women [33], about twice as high all at time: 90 days, 6-months, and 1 year. This study found a higher risk of mortality in men than in women not only at 1-year but also at 90 days and 6 months.

Secondary fracture prevention is an essential goal of hip fracture treatment. In this case series, the proportion of patients receiving anti-osteoporosis pharmacotherapy before the injury was low (21.2%). Precisely 9.7% had a history of contralateral hip fracture, but only one-third (22/66) were on anti-osteoporotic drug therapy at the time of injury. According to a previous Japanese report, the rate of anti-osteoporosis pharmacotherapy was only 19.6% of patients during their hospitalization, and only 18.7% at the 1-year follow-up period after discharge from the first hospital [34]. However, in recent years, the importance of the FLS has been recognized in Japan, and the FLS are spreading [35]. Our approach of cooperation with ward pharmacists improved anti-osteoporosis pharmacotherapy during hospitalization, and the function of the FLS after discharge resulted in a high continuation rate of pharmacotherapy. Nonetheless, in Japan, secondary fracture prevention is not covered by public health insurance, and thus, the FLS is supported by the voluntary efforts of individual medical facilities. Therefore, we need to persuade the government to cover FLS by public health insurance.

In regard to the medical cost, the average total hospitalization costs per patient at our hospital with multidisciplinary treatment had been lower than those in other hospitals/year. The fact that the average time to surgery and length of stay in our hospital are shorter than national ones could be considered as the main factors contributed to a lower medical cost. The impressive aspect of our model is the ability to generate cost savings while still providing patients with high-quality care, including not only perioperative management such as low morbidity and mortality but secondary fracture prevention.

In Japan, a multidisciplinary treatment approach for geriatric fractures is rare. With only a few geriatricians on hand, our initial development of a closer collaboration with internal medicine and all other departments related to hip fracture treatment was beneficial to patients’ treatment and care. Furthermore, we were able to establish the first joint care model in Japan with few available geriatricians for geriatric fractures. Knowing the benefits of this model, we believe that it could be implemented in Japan as a nationwide effort to further improve hip fracture patients’ treatment, care, and monitoring.

Limitations

Although our multidisciplinary care approach has several benefits, our study does not preclude limitations. First, we conducted our research at a single hospital in Japan. Our study was of a retrospective cohort type, which depends on data availability and accessibility from medical records for the identification of patients’ complications. Especially for delirium as a postoperative complication, the diagnostic method for patients with dementia was ambiguous, so the incidence was expected to be higher. Furthermore, in this study, it was possible to investigate mortality, but we could not investigate long-term functional recovery.

However, one of the strengths of this investigation is that it was the first study in Japan, one of the world’s most prominent aging societies, to improve the course of elderly patients with hip fractures, by treating with integrated orthogeriatric care.

Conclusions

This is the report of implementing a multidisciplinary treatment approach for geriatric hip fracture in Japan for the first time, and the second report from our hospital facility. It involved comprehensive geriatric treatment and care that involved different disciplines. As a result, time to surgery and hospital stay were shorter than the national average, the morbidity of serious complications such as pneumonia and heart failure, in-hospital mortality, and 1-year mortality was equal or lower than the joint care model. High rate of osteoporosis treatment at discharge and follow-up were obtained. The total medical cost per person was less than the national average. Thus, our multidisciplinary treatment approach for geriatric hip fractures was effective and feasible to conduct in Japan.

References

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan. Life expectancy Report. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/life/life16/dl/life16-04.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2020

Orimo H, Yaegashi Y, Hosoi T, Fukushima Y, Onoda T, Hashimoto T, Sakata K (2016) Hip fracture incidence in Japan: estimates of new patients in 2012 and 25-year trends. Osteoporos Int 27:1777–1784

Hagino H (2012) Fragility fracture prevention: review from a Japanese perspective. Yonago Acta Med 55:21–28

Adunsky A, Lerner-Geva L, Blumstein T, Boyko V, Mizrahi E, Arad M (2011) Improved survival of hip fracture patients treated within a comprehensive geriatric hip fracture unit, compared with standard of care treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 12:439–444

Vidan M, Serra JA, Moreno C, Riquelme G, Ortiz J (2005) Efficacy of a comprehensive geriatric intervention in older patients hospitalized for hip fracture: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 53:1476–1482

Gonzalez-Montalvo JI, Alarcon T, Mauleon JL, Gil-Garay E, Gotor P, Martin-Vega A (2010) The orthogeriatric unit for acute patients: a new model of care that improves efficiency in the management of patients with hip fracture. Hip Int 20:229–235

Friedman SM, Mendelson DA, Bingham KW, Kates SL (2009) Impact of a comanaged Geriatric Fracture Center on short-term hip fracture outcomes. Arch Intern Med 169:1712–1717

Leung AH, Lam TP, Cheung WH, Chan T, Sze PC, Lau T, Leung KS (2011) An orthogeriatric collaborative intervention program for fragility fractures: a retrospective cohort study. J Trauma 71:1390–1394

Folbert EC, Hegeman JH, Gierveld R, van Netten JJ, Velde DV, Ten Duis HJ, Slaets JP (2017) Complications during hospitalization and risk factors in elderly patients with hip fracture following integrated orthogeriatric treatment. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 137:507–515

Folbert EC, Hegeman JH, Vermeer M, Regtuijt EM, van der Velde D, Ten Duis HJ, Slaets JP (2017) Improved 1-year mortality in elderly patients with a hip fracture following integrated orthogeriatric treatment. Osteoporos Int 28:269–277

Baroni M, Serra R, Boccardi V, Ercolani S, Zengarini E, Casucci P, Valecchi R, Rinonapoli G, Caraffa A, Mecocci P, Ruggiero C (2019) The orthogeriatric comanagement improves clinical outcomes of hip fracture in older adults. Osteoporos Int 30:907–916

Neuerburg C, Förch S, Gleich J, Böcker W, Gosch M, Kammerlander C, Mayr E (2019) Improved outcome in hip fracture patients in the aging population following co-managed care compared to conventional surgical treatment: a retrospective, dual-center cohort study. BMC Geriatr 19:330

Shigemoto K, Sawaguchi T, Goshima K, Iwai S, Nakanishi A, Ueoka K (2019) The effect of a multidisciplinary approach on geriatric hip fractures in Japan. J Orthop Sci 24:280–285

Grimes JP, Gregory PM, Noveck H, Butler MS, Carson JL (2002) The effects of time-to surgery on mortality and morbidity in patients following hip fracture. Am J Med 112:702–709

Bergeron E, Lavoie A, Moore L, Bamvita JM, Ratte S, Gravel C, Clas D (2006) Is the delay to surgery for isolated hip fracture predictive of outcome in efficient systems? J Trauma 60:753–757

Khan SK, Kalra S, Khanna A, Thiruvengada MM, Parker MJ (2009) Timing of surgery for hip fractures: a systematic review of 52 published studies involving 291,413 patients. Injury 40:692–697

Shiga T, Wajima Z, Ohe Y (2008) Is operative delay associated with increased mortality of hip fracture patients? Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Can J Anaesth 55:146–154

Hagino H, Endo N, Harada A, Iwamoto J, Mashiba T, Mori S, Ohtori S, Sakai A, Takada J, Yamamoto T (2017) Survey of hip fractures in Japan: recent trends in prevalence and treatment. J Orthop Sci 22:909–914

Moja L, Piatti A, Pecoraro V, Ricci C, Virgili G, Salanti G, Germagnoli L, Liberati A, Banfi G (2012) Timing matters in hip fracture surgery: patients operated within 48 hours have better outcomes. A meta-analysis and meta-regression of over 190,000 patients. PLoS ONE 7:e46175

Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, Curley C, Dahl OE, Schulman S, Ortel TL, Pauker SG, Colwell CW Jr (2012) Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 141:e278S-e325S

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. Evidence-based guidelines and evidence report. http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/VTE/VTE_full_guideline.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2020

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Venous thromboembolism in over 16s: reducing the risk of hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng89. Accessed 5 May 2020

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of hip fractures in older people. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2009. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign111.pdf. Accessed May 5 2020

The management of hip fracture in adults. March 2014. guidance.nice.org.uk/cg124. Roberts KC, Brox WT.

Roberts KC, Brox WT (2015) AAOS clinical practice guideline: management of hip fractures in the elderly. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 23:138–140

Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) Trial Collaborative Group (2000) Prevention of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis with low dose aspirin: pulmonary embolism prevention (PEP) trial. Lancet 355:1295–1302

Eriksson BI, Bauer KA, Lassen MR, Turpie AGG for the Steering Committee of the Pentasaccharide in Hip‐Fracture Surgery Study (2001) Fondaparinux compared with enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after hip-fracture surgery. N Engl J Med 345:1298–1304

Rosencher N, Vielpeau C, Emmerich J, Emmerich J, Fagnani F, Samama CM, ESCORTE group (2005) Venous thromboembolism and mortality after hip fracture surgery: the ESCORTE study. J Thromb Haemost 3:2006–2014

Thaler HW, Roller RE, Greiner N, Sim E, Korninger C (2001) Thromboprophylaxis with 60 mg enoxaparin is safe in hip trauma surgery. J Trauma 51:518–521

Barrera LM, Perel P, Ker K, Cirocchi R, Farinella E, Morales Uribe CH (2013) Thromboprophylaxis for trauma patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3):CD008303

Adunsky A, Nenaydenko O, Koren-Morag N, Puritz L, Fleissig Y, Arad M (2015) Perioperative urinary retention, short-term functional outcome and mortality rates of elderly hip fracture patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int 15:65–71

Roche JJW, Wenn RT, Sahota O, Moran CG (2005) Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: prospective observational cohort study. Br Med J 331:1374–1376

Guzon-Illescas O, Perez Fernandez E, Crespí Villarias N, Quirós Donate FJ, Peña M, Alonso-Blas C, García-Vadillo A, Mazzucchelli R (2019) Mortality after osteoporotic hip fracture: incidence, trends, and associated factors. J Orthop Surg Res 14:203

Hagino H, Sawaguchi T, Endo N, Ito Y, Nakano T, Watanabe Y (2012) The risk of a second hip fracture in patients after their first hip fracture. Calcif Tissue Int 90:14–21

Hagino H, Wada T (2019) Osteoporosis liaison service in Japan. Osteoporos Sarcopenia 5:65–68

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely acknowledge Prof. Michael Blauth, past professor in the Department of Trauma Surgery, Medical University of Innsbruck, and Dr. Markus Gosch, Professor for Geriatric Medicine at the Paracelsus Private Medical University in Nuremberg, for their guidance and support in the multidisciplinary approach. The authors would also like to thank the members of our multidisciplinary team for geriatric hip fracture at Toyama City Hospital.

Funding

There is no funding source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shigemoto, K., Sawaguchi, T., Horii, T. et al. Multidisciplinary care model for geriatric patients with hip fracture in Japan: 5-year experience. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 142, 2205–2214 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-021-03933-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-021-03933-w