Abstract

Background

Success rates of up to 80% have been reported for the SNM screening period in the treatment of fecal incontinence (FI). Some patients who have an unsuccessful index implantation are successfully treated with SNM after a lead revision. There is a lack of studies comparing the outcomes of successful index implantations and successful lead revision. Therefore, the results of index implantations were compared with lead revisions in a single-center cohort.

Methods

Patients treated with SNM for FI between 2008 and 2016 were retrospectively reviewed. Patients with a successful index implantation were compared with patients who underwent lead revision after SNM screening. Primary outcome was a decrease in episodes of fecal incontinence of ≥ 50% documented by a 3-week bowel habit diary.

Results

Two hundred sixty-one patients (232 index group, 29 revision group) were eligible for SNM. Two hundred thirty-one patients (208 index group, 23 revision group) received permanent SNM. Follow-up was 68.8 months for the index group and 62.2 months for the revision group. The number of episodes of FI decreased from 20.6 (SD 19.3) to 3.4 (SD 4.2) in the index group and from 12.6 (SD 5.8) to 2.0 (SD 2.3) in the revision group. This effect was maintained up to 5 and 2 years in the index and revision group, respectively. Adverse events such as loss of efficacy which required surgical intervention did not differ between the two groups.

Conclusion

Lead revision during the test phase is a valid option in patients with FI treated by SNM who suffer from loss of efficacy of the index electrode.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sacral neuromodulation (SNM) is a valid treatment option for fecal incontinence (FI) [1, 2]. SNM is two-phase procedure that consists of placing an electrode in the third sacral foramen followed by a screening period of 3 to 4 weeks. If the number of incontinent episodes is improved by at least 50%, an implantable pulse generator (IPG) is implanted in the buttocks. Several large studies reported success rates ranging between 47.7 and 54% based on an analysis of the entire cohort [1, 3]. However, few studies report on the success rate of the SNM screening period. Success rates of up to 80% have been reported for the SNM screening period for FI [2, 4].

Adverse events have also been reported after implantation of SNM for FI [5]. The most common adverse events include pain and discomfort at the site of implantation, infections, lack of efficacy, and loss of efficacy [6]. Lack or loss of efficacy over time is reported in 49.4% and up to 88.1% of patients who received permanent SNM for FI [6, 7]. This can initially be treated with conservative options such as changing stimulation settings after mechanical failure has been excluded. However, a surgical revision of the lead is inevitable if these conservative options fail. Lack or loss of efficacy mostly occurs within the first 2 years after implantation of permanent SNM [6]. However, lack or loss of efficacy can also occur during the SNM screening period. There is a lack of studies reporting on the long-term outcomes of lead reimplantation after lack or loss of efficacy during the initial screening period [8].

We report the results of index implantations compared with lead revisions after the initial screening period in a single-center cohort.

Methods

Study population

Patients treated with SNM for FI between March 2008 and December 2016 were retrospectively reviewed. All patients failed conservative treatment. All patients underwent a two stage SNM procedure. Stage 1 consisted of a percutaneous lead placement followed by a 4-week test period. If patients had a ≥ 50% improvement of incontinent episodes after the SNM screening period compared with baseline, a permanent IPG was implanted (stage 2).

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they suffered from chronic skin conditions, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic diarrhea unresponsive to pharmacological or dietary treatments, congenital colorectal malformations, existing rectal prolapse, chronic constipation leading to FI, and neurological or psychiatric comorbidities. Pregnant patients and patients with a stoma in situ were also excluded.

Operative treatment

The operative technique for SNM has been described previously [9]. During stage 1, patients are placed in a prone position and anatomical landmarks are marked. Stage 1 is conducted under general or local anesthesia depending on patient’s preference. A needle is used to identify the sacral foramina under fluoroscopic guidance to test the neurological response. After an adequate motor and/or sensory response is achieved, the foramen which elicits the best responses is chosen for lead placement. A tunneled, quadripolar tined lead (tined lead procedure (TLP) (Interstim model 3093/3889)) is then inserted in the identified foramen and correct placement is confirmed by fluoroscopy. Afterwards, the electrode is connected to an external stimulator (Medtronic model 3625/3531) for a 4-week SNM screening period. If patients meet the criteria for permanent implantation, the IPG for permanent SNM is implanted (stage 1). During stage 1, the external stimulator is disconnected from the tined lead and an IPG (Medtronic 3058/3023) is connected and placed subcutaneously in the gluteal region.

Outcomes and assessment

Primary outcome was defined as a reduction of ≥ 50% in the number of episodes of involuntary fecal loss. Primary outcome was evaluated by comparing the 4-week bowel habit diary at different follow-up moments with baseline. Secondary outcomes were defined as a reduction in defecation frequency and an increase in time postponing defecation at the sensation of urge.

Besides, the number of patients suffering from loss of efficacy which required surgical intervention after implantation of the IPG was assessed. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, the lack and loss of efficacy could not be identified separately. Follow-up was scheduled at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after SNM implantation. After the first year, follow-up was scheduled annually. In case of loss of efficacy, patients were seen at the outpatient clinic in between regular follow-up on their initiative.

Loss of efficacy

Loss of efficacy is defined as reduced or loss of therapeutic effect of SNM on FI after implantation of the electrode without using conservative options or reprogramming the stimulator. Loss of efficacy was first treated with conservative options. The electrode and IPG were checked for technical failure. If technical failure was excluded, the stimulation settings were reprogrammed according to the algorithm of Dudding et al. [10] An X-ray of the pelvis was performed in all patients who suffered from loss of efficacy to exclude lead migration and lead fracture. If efficacy was not restored by conservative options, patients were offered a lead revision. In case of technical failure, a new lead was inserted in the identical foramen. In case of clinical failure, the new lead was placed in the contralateral foramen. A lead revision was discussed with all patients who suffered from loss of efficacy; however, some patients did not want a lead revision and their lead was removed.

Statistical analysis

Patients were divided into two groups: the index implantation group (patients with successful SNM after one TLP) and the revision group (patients with successful SNM after > 1 TLP). Each patient served as his own control and outcomes of follow-up moments were compared with baseline data. Data were presented as mean (SD) for continuous variables and count (percentage) for categorical variables. Percentages were calculated based on the entire number of patients per group, including the patients who failed SNM screening. Statistical testing was based on the paired t test for paired samples. The chi-square test was used for non-paired samples. Statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05. Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 23 for Windows, IBM).

Results

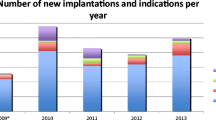

Two hundred sixty-one patients were included for a SNM screening period. Of these, 232 patients only had one TLP and were included in the index implantation group. Twenty-nine patients had > 1 TLP and were included in the revision group. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

In total, 231 patients received a permanent SNM implant: 208 patients (89.7%) in the index implantation group and 23 patients (79.3%) in the revision group (p = 0.096). Of the patients with permanent SNM, 27 patients (11.6%) in the index implantation group and one patient (3.4%) revision group were loss to follow-up (p = 0.15). Due to unsatisfactory results, SNM was removed in 29 patients (12.5%) in the index implantation group and 6 patients (20.7%) in the revision group (p = 0.12). Clinical efficacy was maintained 64.7% of patients in the index implantation group and in 55.2% of patients in the revision group (p = 0.44) (Fig. 1).

Primary outcome

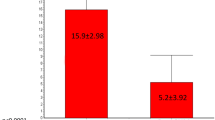

Episodes of fecal incontinence decreased from 20.6 (SD 19.3) to 3.4 (SD 4.2) after the 3-week SNM screening period in the index implantation group (p < 0.001). The beneficial effect was maintained up to 5 years of follow-up (p < 0.001). In the revision group, episodes of fecal incontinence decreased from 12.6 (SD 5.8) to 2.0 (SD 2.3) after the SNM screening period (p = 0.04). This effect was maintained up to 2 years of follow-up (p = 0.035). There was no difference between both groups regarding the number of episodes of FI during a follow-up of 2 years (p = 0.12) (Fig. 2).

Secondary outcomes

Defecation frequency decreased from 2.8 (SD 1.7) to 1.9 (SD 1.1) defecations per day after the SNM screening period (p < 0.001) and remained lower compared with baseline up to 1 year of follow-up (p = 0.026) in the index implantation group. Daily defecation frequency in the revision group decreased from 2.4 (SD1.1) at baseline to 1.7 (SD 0.5) after the SNM screening period (p = 0.051). However, the decrease in defecation frequency was not significant during entire follow-up (p = 0.81). Defecation frequency did not differ between the two groups during a follow-up of 2 years (Fig. 3).

The time period to defer defecation upon the sensation of urge increased from 1.4 (SD 1.91) minutes at baseline to 8.9 (SD 13.1) after the SNM screening period in the index implantation group (p < 0.001). This beneficial effect was maintained up to 1 year of follow-up (p < 0.001). In the revision group, the time to defer defecation upon the sensation of urge increased from 0.8 (SD 0.9) min at baseline to 6.1 (SD 6.2) min after the SNM screening period. The time to defer defecation remained up to 2 years of follow-up (p = 0.032). The time to postpone defecation upon the sensation of urge did not differ between the two groups during 2 years of follow-up (Fig. 4).

Loss of efficacy

A total of 71 patients suffered from loss of efficacy, 63 patients (27.2%) in the index implantation group, and eight (27.6%) patients in the revision group (p = 0.53).

Fifty-seven patients of the index implantation group received a new electrode. Seventeen patients with technical failure received a new, ipsilateral electrode and 40 patients with clinical failure received a contralateral electrode. SNM was removed in one patient after lead revision for technical failure and in 22 patients after lead revision for clinical failure.

Six patients in the revision group received a new electrode due to clinical failure. No patients in the revision group suffered from loss of efficacy due to technical failure. SNM was removed in four of the six patients after lead revision for clinical failure.

Discussion

This study shows that fecal incontinent patients who underwent a successful lead revision after unsuccessful index implantation have a similar outcome compared with patients with a successful index implantation (index implantation group vs revision group; 64.7% vs 55.2%). A ≥ 50% decrease in episodes of FI was maintained up to 5 years and 2 years in the index implantation group and revision group, respectively. There was no difference between both groups regarding the number of FI during 2 years of follow-up. In both groups, defecation frequency decreased and time to postpone defecation increased after SNM. These outcomes did not differ between the groups. Furthermore, the loss of efficacy was comparable in both groups (index implantation group vs revision group; 27.2% vs 27.6%).

The success rates of the SNM screening period were 89.7% for the index implantation group and 79.3% for the revision group. These results are comparable with previous studies that reported success rates based on intention to treat (ITT) analysis ranging from 66.8 up to 71.8% [1, 6]. Furthermore, the outcomes of both groups of permanent SNM were comparable with previous studies who reported success rates, based on ITT analysis, ranging from 47.7 up to 54% [1, 3]. However, it is unknown whether these studies have included patients with a lead revision during or after the SNM screening period.

To our knowledge, only one study by Cracco et al. compared the outcomes of SNM for FI between patients with a lead revision and patients with a successful index implantation [8]. Outcomes were based on the Cleveland Clinic Florida Fecal Incontinence Scores (CCF-FISs) and showed that patients who had a successful index implantation had significantly more improvements compared with patients who underwent lead revision. Our results are in line with this previous study as patients with a successful index implantation had a better outcome after 5 years of follow-up compared with patients with a lead revision. However, results should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of patients in the revision group and missing data during follow-up.

Loss of efficacy and infections at the site of the implants are the two most common adverse events related to SNM. Loss of efficacy has been reported to occur in up to 49.4% of patients with SNM for FI based on ITT analysis [4, 6]. Infections are reported ranging from 2 up to 7.4% [4, 6, 8]. Loss of efficacy occurred in 27.2% and 27.6% in the index implantation and revision group, respectively. Although our results appear to be better than previous studies, patients suffering from loss of efficacy which was restored by conservative interventions could not be identified due to the retrospective study design. Therefore, the percentage of patients suffering from loss of efficacy is probably higher.

The current literature is lacking a uniform definition of loss of efficacy. Our definition of loss of efficacy is comparable with previous studies who defined it as reduced or loss of therapeutic effect after implantation of the IPG after a period with good effect [4, 6]. However, other studies defined loss of efficacy as a reduction in therapeutic effect unresponsive to dietary changes, medical therapies, or reprogramming of the stimulator [8]. Furthermore, there are also studies that do not mention a definition of loss of efficacy [1, 11]. Reports on loss of efficacy should therefore be compared with care.

This study was limited by its uncontrolled, retrospective design. Moreover, results should be interpreted with caution as the revision group only included 29 patients. During the past 5 years, bowel habit diaries were not routinely collected which resulted in missing follow-up data regarding defecation frequency and time to postpone defecation. These missing data could not be used for paired testing.

Clinical efficacy of SNM in the treatment of fecal incontinence is comparable between patients with successful, index implantation, and patients who have had a lead revision. Adverse events were similar in both groups. In conclusion, lead revision should be routinely considered and discussed with the patients in case of loss of efficacy.

References

Altomare DF, Giuratrabocchetta S, Knowles CH, Munoz Duyos A, Robert-Yap J, Matzel KE et al (2015) Long-term outcomes of sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence. Br J Surg 102(4):407–415

Melenhorst J, Koch SM, Uludag O, van Gemert WG, Baeten CG (2007) Sacral neuromodulation in patients with faecal incontinence: results of the first 100 permanent implantations. Color Dis 9(8):725–730

Thin NN, Horrocks EJ, Hotouras A, Palit S, Thaha MA, Chan CL et al (2013) Systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of neuromodulation in the treatment of faecal incontinence. Br J Surg 100(11):1430–1447

Janssen PT, Kuiper SZ, Stassen LP, Bouvy ND, Breukink SO, Melenhorst J (2017) Fecal incontinence treated by sacral neuromodulation: long-term follow-up of 325 patients. Surgery. 161:1040–1048

Wexner SD, Coller JA, Devroede G, Hull T, McCallum R, Chan M, Ayscue JM, Shobeiri AS, Margolin D, England M, Kaufman H, Snape WJ, Mutlu E, Chua H, Pettit P, Nagle D, Madoff RD, Lerew DR, Mellgren A (2010) Sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence: results of a 120-patient prospective multicenter study. Ann Surg 251(3):441–449

Maeda Y, Lundby L, Buntzen S, Laurberg S (2011) Suboptimal outcome following sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence. Br J Surg 98(1):140–147

Govaert B, Rietveld MP, van Gemert WG, Baeten CG (2011) The role of reprogramming in sacral nerve modulation for faecal incontinence. Color Dis 13(1):78–81

Cracco AJ, Chadi SA, Rodrigues FG, Zutshi M, Gurland B, Wexner SD, DaSilva G (2016) Outcomes of sacral neurostimulation lead reimplantation for fecal incontinence: a cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum 59(1):48–53

Martellucci J (2015) The technique of sacral nerve modulation. Color Dis 17(4):O88–O94

Dudding TC, Hollingshead JR, Nicholls RJ, Vaizey CJ (2011) Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence: optimizing outcome and managing complications. Color Dis 13(8):e196–e202

Zeiton M, Faily S, Nicholson J, Telford K, Sharma A (2016) Sacral nerve stimulation--hidden costs (uncovered). Int J Color Dis 31(5):1005–1010

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PJ, JM, LS, NB, and SB designed the study; PJ performed the research; PJ, JM, and SB analyzed and interpreted the data; PJ, JM, LS, NB, and SB drafted the manuscript; JM, LS, NB, and SB supervised the study. All authors gave final approval of the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

PJ, JM, and SB received a non-restrictive grant from Medtronic for research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Presented as a poster presentation during the 12th Scientific and Annual General Meeting of the European Society of Coloproctology, 20–22 September 2017 Berlin.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Janssen, P.T.J., Melenhorst, J., Stassen, L.P.S. et al. Clinical efficacy of lead revisions during the test phase in sacral neuromodulation for fecal incontinence. Int J Colorectal Dis 34, 1369–1374 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03325-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-019-03325-y