Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM) of the spinal cord represents a rare entity in children and account for less than 1% of all central nervous system (CNS) cancers. Their biology, localization, and controversial treatment options have been discussed in a few pediatric cases. Here, we report a case of primary spinal cord glioblastoma in a 5-year-old girl having the particularity to be extended to the brainstem. This tumor has been revealed by torticollis and bilateral brachial paresis. The patient underwent subtotal resection; unfortunately, she died in reanimation 1 week later by severe pneumopathy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case in the literature reporting this particular localization in a child. Beyond their dismal prognosis, we discuss the rarity of the disease and describe the peculiar characteristics, management, and prognosis of this rare tumor in pediatric oncology. This case appears to be unusual for both the histological type and the extension to brain stern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Spinal cord glioblastoma (GBM) accounts for approximately 7.5% of all intramedullary gliomas and 1.5% of all spinal cord tumors [7]. These tumors are only rarely seen in children and represents 1–5% of all GBMs [20, 28].They have a predilection for development in the cervical or cervicothoracic region and are associated with severe disability and poor prognosis.

Here, we report a case of primary spinal cord glioblastoma having the particularity to be extended to the brainstem. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case in the literature reporting this particular localization in a child. This case appears to be unusual for both the histological type and the extension to brains tern.

Little is known about the peculiar clinical characteristics of primary spinal glioblastomas and his optimal treatment. However, this report describes one case of cervical glioblastoma in a 5-year-old child and reviews other cases reported in the literature (Table 1) and discuss the clinical features, current multidisciplinary therapeutic approaches, and prognostic factors of this rare pathology with a review of pertinent literature.

Case Description

Clinical Presentation

A 5-year-old girl presented at our department complaining of severe cervical back pain, torticollis, and progressive weakness of her two upper limbs. Clinical examination found a conscious child, having severe torticollis (Fig. 1) and symmetric bilateral brachial paresis. No neurological deficit was found in the lower limbs.

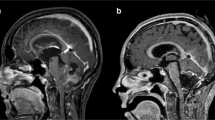

Plain X-rays were normal, although CT scan showed an enlargement of the cervical spinal canal. However, MRI revealed a large and a heterogeneous cervical intramedullary mass with irregular enhancement after gadolinium injection that filled the spinal canal until T2. The mass was extended from the bulbo-medullary junction to the cervicothoracic spinal cord (T2) and appear hyposignal T1 and hypersignal T2. Craniospinal MRI did not show any signs of hydrocephalus or leptomeningeal metastases (Fig. 2).

The patient underwent surgery, and the tumor was approached through a suboccipital craniotomy, C1 laminectomy, and C2–C7 laminotomy. Microsurgical subtotal excision was performed with intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring. After opening the dura, a greyish, highly vascularized solid mass appeared, infiltrating the cervical spinal cord and the brain stem. At the end of the procedure, the excision appeared to be partial because the infiltration of brain stern (Fig. 3).

Histopathology

Microscopy demonstrates a neoplastic proliferation of polymorphous glial cells characterized by anisocaryosis and atypical mitosis, focal necrosis, calcifications, and areas with multinucleated cells are present. Moreover, immunohistochemistry shows positivity for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and S100 and negativity for sinaptofisine, neurofilaments, and the epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). The final histological study was compatible with spinal cord glioblastoma (GBM).

Outcome

In the immediate postoperative stage, the patient developed quadriplegia with breathing difficulties. She was hospitalized in the intensive care unit where unfortunately, she died 1 week later because of severe nosocomial pneumonia.

Discussion

Intramedullary gliomas are uncommon clinical entities especially in children accounting for less than 10% of all central nervous system tumors [11]. Data on childhood malignancies from the European Union show that only 3% of all children with CNS tumors are affected by this disease [10]. These tumors are often misdiagnosed or diagnosed late because of their rarity. The commonly reported locations of GBM are the cervicothoracic segments, with the cervical spine being the most affected region, followed by the thoracic spine [24]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no other radiologic reports of primitive glioblastoma in cervical spine extended to brain stern in childhood.

The study of Konar et al. showed that the mean age at presentation for primary spinal GBM was 10 ± 5.1 years [13]. Clinical presentation is related to the region of spinal cord involved. The most common symptoms in children include pain, motor regression, torticollis, and progressive kyphoscoliosis. These lesions are highly aggressive, with rapid neurological deterioration and death following a short clinical history [8] as seen in this report, usually less than a year [6].

However, spinal cord glioblastoma shows a tendency to spread via the subarachnoid space at the spinal and, more rarely, at the brain level. This can be explained by the proximity of the neoplastic cells to the cerebrospinal fluid pathways [5]. In the same way, the extension to the brain stern may be a tumoral progression from spinal cord or on the contrary the starting point of GBM. These patients develop not only local recurrences but frequently widespread leptomeningeal metastases.

MRI is the diagnostic procedure of choice for spinal tumors. In the presented case, MRI was able to accurately define the tumor extending from brain stern to T2. Full neuraxis MRI is always recommended in order to detect possible metastases. The main aim of the differential diagnosis of gliomas in the pediatric population is to exclude demyelinating disease, neurosarcoidosis, vascular malformations, ischemia, pseudotumor, chronic arachnoiditis, transverse myelitis, gangliogliomas, ependymomas, and epidermoid/dermoid tumors [7].

Historically, pediatric spinal GBM has been treated surgically with adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) followed by chemotherapeutic regimens, although neoadjuvant chemotherapy did not offer any survival benefit compared with RT and adjuvant standard chemotherapy [29].

In addition, controversial management protocol and contradictory reports on the benefit of resection, radiation, and chemotherapy limit neurosurgeons’ or oncologists’ ability to formulate clear guidelines and consensus on optimal treatment strategies. However, some studies have advocated for aggressive surgical removal, but the lack of a clear plane between the infiltrative tumor and the adjacent normal tissue makes total removal largely unrealizable [8]. Furthermore, treatment always requires an individual decision-making process. Although surgical decompression/resection of spinal cord GBM is the treatment of choice (with varying degree of extent of resection ranging from partial debulking to gross total resection and even cordectomy), it is often accompanied by significantly increased morbidity without necessarily increase survival; therefore, some authors recommend biopsy [7]. Use of chemotherapy and temozolomide may prove helpful, despite aggressive treatment combining surgery and irradiation [4]. Moreover, laminoplasty should be performed in spinal surgery in children, to avoid the high incidence of spinal deformities following laminectomy [5].

Pediatric GBM usually has a grim prognosis. Many reported cases had survival ranges from 6 and 16 months, with a mean survival period of 12 months after diagnosis [20]. An exceptionally long survival of 144 months has been reported for a patient with spinal GBM [30]. In the analysis of Adams et al., only the histological subtype, age at diagnosis (child and adult), sex, and the extent of resection were associated with survival [1]. On the other hand, Liu et al. report that tumor size and the extend of surgery had no significant impact on survival of adult patients, whereas postoperative radiotherapy is associated with prolonged survival [16] (Table 1).

The analysis of all published cases of spinal GBM (Table 1) demonstrate female predominance with sex ratio ½, and GTR performed only in 29% with median survival of 17 months against 8 and 11 months after STR/Biopsy and all resection degrees, respectively. In addition, half of the cases underwent chemotherapy, 78% radiotherapy, and only 6 cases without any adjuvant treatment (RT/CT) with median survival of 2 months. Also, further studies are required to elucidate the best treatment strategy for pediatrics spinal cord glioblastoma.

Conclusion

Spinal cord glioblastoma is a deadly disease that is so rare, exceptionally extends to brain stern with grim prognosis. Even with aggressive management, these tumors are generally associated with a dismal outcome.

Abbreviations

- GBM:

-

Glioblastoma

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

References

Adams H, Avendano J, Raza SM, Gokaslan ZL, Jallo GI, Quinones-Hinojosa A (2012) Prognostic factors and survival in primary malignant astrocytomas of the spinal cord: a population-based analysis from 1973 to 2007. Spine 37(12):E727–E735

Adams H, Adams HH, Jackson C, Rincon-Torroella J, Jallo GI, Quiñones-Hinojosa A (2016) Evaluating extent of resection in pediatric glioblastoma: a multiple propensity score-adjusted population-based analysis. Childs Nerv Syst 32:493–503

Ansari M, Nasrolahi H, Kani AA, Mohammadianpanah M, Ahmadloo N, Omidvari S et al (2012) Pediatric glioblastoma multiforme: a single-institution experience. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 33:155–160

Bonde V, Balasubramaniam S, Goel A (2008) Glioblastoma multiforme of the conus medullaris with holocordal spread. J Clin Neurosci 15(5):601–603

Caroli E, Salvati M, Ferrante L (2005) Spinal glioblastoma with brain relapse in a child: clinical considerations. Spinal Cord 43(9):565–567

Ciappetta P, Salvati M, Capoccia G et al (1991) Spinal glioblastoma: report of seven cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 28:302–306

Fayçal L, Mouna B, Najia EA (2017) Rare case of conus medullaris glioblastoma multiforme in a teenager. Surg Neurol Int 8:234

Hernández-Durán S, Bregy A, Shah AH, Hanft S, Komotar RJ (2015) Manzano GR Primary spinal cord glioblastoma multiforme treated with temozolomide. J Clin Neurosci 22(12):1877–1882

Johnson DL, Schwarz S (1987) Intracranial metastases from malignant spinal-cord astrocytoma. Case report. J Neurosurg 66:621–625

Kaatsch P, Rickert CH, Kuhl J, Schuz J, Michaelis J (2001) Population-based epidemiologic data on brain tumors in German children. Cancer 92(12):3155–3164

Khalil J, Chuanying Z, Qingb Z, Belkacémi Y, Mawei J (2017) Primary spinal glioma in children: results from a referral pediatric institution in Shanghai. Cancer Radiother 21(4):261–266

Kim WH, Yoon SH, Kim CY, Kim KJ, Lee MM, Choe G et al (2011) Temozolomide for malignant primary spinal cord glioma: an experience of six cases and a literature review. J Neurooncol 101:247–254 (Erratum in J Neurooncol101:255, 2011)

Konar SK, Bir SC, Maiti TK, Nanda A (2017) A systematic review of overall survival in pediatric primary glioblastoma multiforme of the spinal cord. J Neurosurg Pediatr 19(2):239–248

Lakhdar F, Benzagmout M, Chakour K, Chaoui FM (2019) Primary bulbo-medullary glioblastoma in a child: case report. Childs Nerv Syst. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-019-04396-6

Lam S, Lin Y, Melkonian S (2012) Analysis of risk factors and survival in pediatric high-grade spinal cord astrocytoma: a population-based study. Pediatr Neurosurg 48:299–305

Liu J, Zheng M, Yang W, Lo SL, Huang J (2018 Sep) Impact of surgery and radiation therapy on spinal high-grade gliomas: a population-based study. J Neuro-Oncol 139(3):609–616

Lober R, Sharma S, Bell B, Free A, Figueroa R, Sheils CW et al (2010) Pediatric primary intramedullary spinal cord glioblastoma. Rare Tumors 2:e48

McGirt MJ, Goldstein IM, Chaichana KL, Tobias ME, Kothbauer KF, Jallo GI (2008) Extent of surgical resection of malignant astrocytomas of the spinal cord: outcome analysis of 35 patients. Neurosurgery 63:55–61

Minehan KJ, Brown PD, Scheithauer BW, Krauss WE, Wright MP (2009) Prognosis and treatment of spinal cord astrocytoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 73:727–733

Mori K, Imai S, Shimizu J, Taga T, Ishida M, Matsusue Y (2012) Spinal glioblastoma multiforme of the conus medullaris with holocordal and intracranial spread in a child: a case report and review of the literature. Spine J 12(1):e1–e6

Narayana A, Kunnakkat S, Chacko-Mathew J, Gardner S, Karajannis M, Raza S, Wisoff J, Weiner H, Harter D, Allen J (2010) Bevacizumab in recurrent high grade pediatric gliomas. Neuro-Oncology 12:985–990

O’Halloran PJ, Farrell M, Caird J, Capra M, O’Brien D (2001) Paediatric spinal glioblastoma: case report and review of therapeutic strategies. Childs Nerv Syst 29:367–374

Perkins SM, Rubin JB, Leonard JR, Smyth MD (2011) El NaqaI, Michalski JM, et al: Glioblastoma in children: a single institution experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 80:1117–1121

Pollack IF (2004) Intramedullary spinal cord astrocytomas in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer 43:617–618

Prasad GL, Borkar SA, Subbarao KC, Suri V, Mahapatra AK (2012) Primary spinal cord glioblastoma multiforme: a report of two cases. Neurol India 60:333–335

Raco A, Esposito V, Lenzi J, Piccirilli M, Delfini R, Cantore G (2005) Long-term follow-up of intramedullary spinal cord tumors: a series of 202 cases. Neurosurgery 56:972–981

Russell DS, Rubinstein LJ (1959) Pathology of tumors of the nervous system. Edward Arnold & Co, London

Timmons JJ, Zhang K, Fong J, Lok E, Swanson KD, Gautam S, Wong ET (2018 Dec) Literature review of spinal cord glioblastoma. Am J Clin Oncol 41(12):1281–1287

Vanan MI, Eisenstat DD (2014) Management of high-grade gliomas in the pediatric patient: past, present, and future. Neurooncol Pract 1(4):145–157

Viljoen S, Hitchon PW, Ahmed R, Kirby PA (2014) Cordectomy for intramedullary spinal cord glioblastoma with a 12 year survival. Surg Neurol Int 5:101

Wisoff JH, Boyett JM, Berger MS, Brant C, Li H, Yates AJ, McGuire-Cullen P, Turski PA, Sutton LN, Allen JC, Packer RJ, Finlay JL (1998) Current neurosurgical management and the impact of the extent of resection in the treatment of malignant gliomas of childhood: a report of the Children’s Cancer Group trial no. CCG-945. J Neurosurg 89:52–59

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lakhdar, F., Benzagmout, M., Chakour, K. et al. Primary bulbo-medullary glioblastoma in a child: case report. Childs Nerv Syst 35, 2417–2421 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-019-04396-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-019-04396-6