Abstract

Background and importance

Giant cavernous malformations (GCM) are low flow, angiographically occult vascular lesions, with a diameter >4 cm. Cerebellar GCMs are extremely rare, with only seven cases reported based on English literature. These lesions are most commonly seen in the pediatric age group, which is known to have an increased risk of hemorrhage, being surgery clearly recommended.

Clinical presentation

An 18-month-old girl presented with a 6-month history of cervical torticollis and upper extremities clumsiness. An MRI revealed a 57 × 46 × 42 mm multi-cystic, left cerebellar hemisphere mass, showing areas of hemorrhages and cysts with various stages of thrombus. There was no enhancement with contrast. Cerebral angiography ruled out an arteriovenous malformation. She underwent a left paramedian occipital craniotomy, and macroscopic gross total resection was accomplished. Histopathologic examination was consistent with a cavernous malformation. After surgery, the patient had no new neurological deficit and an uneventful postoperative recovery. Follow-up MRI confirmed total removal of the lesion.

Conclusion

Cerebellar GCMs in children are symptomatic lesions, which prompt immediate surgical treatment. These are rare lesions, which can radiologically and clinically mimic a tumor with bleed, having to be considered in the differential diagnosis of neoplastic lesions. Cerebellar GCMs might be suspected in the presence of large hemorrhagic intra-axial mass with “bubbles of blood,” multi-cystic appearance, surrounded by hemosiderin ring, fluid-fluid levels, and accompanying edema-mass effect. Careful radiological study provides a preoperative diagnosis, but its confirmation requires histopathological examination. Complete surgical removal should be attempted when possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cavernous malformations (CM) are low flow, angiographically occult vascular lesions. They account for 5–13% of all intracranial vascular anomalies, having an incidence of 0.4–0.9% in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and autopsies studies [1,2,3,4]. Their prevalence in children is around 0.37 and 0.53% [5, 6]. CMs vary in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters, with a reported mean size of 1.4 cm in diameter [7, 8]. Kan et al. have defined these rare giant cavernous malformations (GCM), as those with a diameter greater than 4 cm [9]. Cerebellar GCMs are extremely rare, with only seven cases reported in English literature [9,10,11,12,13]. There is an eighth case report not considered in this review for further analysis, due to the fact it is written in Russian [14]. The pathophysiology of GCMs is unclear, and patients present usually with symptoms of seizures, hemorraghes, mass effect, or neurologic deficits. CMs in children have an increased hemorrhage risk and more aggressive behavior compared to adults [5, 6]. Imaging features of GCMs are variable, including a tumefactive pattern with edema and mass effect, which can be mistaken as neoplasms [9, 10, 15]. Because cerebellar GCMs are extremely rare and usually not considered in the differential diagnosis of tumors, we present a case of a cerebellar GCM in an 18-month-old girl and review of the literature on clinical presentation, radiological features, surgical management, and outcome of cerebellar GCM.

Case report

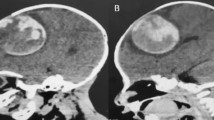

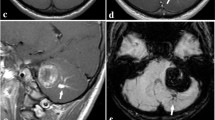

A previously healthy 18-month-old girl presented with a 6-month history of progressive cervical torticollis aggravated in the last week with upper extremities clumsiness. On examination, she had limited cervical rotation to the right and left-sided clumsiness. The rest of the examination was unremarkable. An MRI revealed a 57 × 46 × 42 mm, multi-cystic, left cerebellar hemisphere mass, showing areas of hemorrhages and cysts with various stages of thrombus. The mass associated a peripheral hypointense rim seen on T2-weighted image and perilesional edema with mass effect. There was no enhancement with contrast, highly suggestive of a cerebellar giant cavernous malformation (GCM) (Fig. 1). Angiography was performed to rule out an arteriovenous malformation. Four days after admission, she underwent a left paramedian occipital craniotomy and a macroscopic gross total resection was accomplished. The multi-lobulated lesion consisted of mulberry-like structures, surrounded by a xanthochromic area. The histopathologic examination revealed multiple dilated vascular spaces lined by endothelium, areas with recent and old hemorrhages and calcifications, consistent with a cavernous malformation. After the surgery, the patient had no new neurological deficit and an uneventful postoperative recovery. During the 6-month follow-up, she had important improvement on her movement’s coordination and torticollis, with a practical normal psychomotor development and no signs of cerebellar affection. Follow-up MRI confirmed total removal of the lesion (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Cavernous malformations represent 5–13% of all the central nervous system vascular malformations. Most commonly located in the cerebral hemispheres, while most of the posterior fossa CMs present in the brainstem, and therefore, cerebellar CMs are rare lesions [15]. Pediatric cerebellar GCMs are extremely rare lesions, with only seven cases reported in English literature (Table 1) [9, 13, 16,17,18]. CMs vary in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters, although GCMs do not have a precise definition and those at the large end of the spectrum are loosely referred to as giant. Kan and Lawton have tried to define GCMs; however, a strict and uniform definition needs to be done for future reports [9, 19].

The etiology and mechanism of growth are still unclear. Amongst the postulated mechanisms are embryogenetic errors during vascular development and de novo genesis secondary to proliferative vasculopathies. It has been suggested that GCMs develop from smaller CMs, and grow when friable vessels, formed by abnormal angiogenesis, cause repeated hemorrhages that excavate or push aside brain, followed by clot organization, pseudocapsule formation, and secondary expansion. The osmotic effect of blood break-down products in the cyst is thought to be the mechanism behind such growth [9, 10, 19].

Based on our literature review, cerebellar GCMs do not have sex preponderance. Six (75%) of them had clinical features of raised intracranial pressure. Due to their large size, all cerebellar GCMs become symptomatic at some point. All of the patients with available CT scan (6 patients; 75%) had a hyperdense lesion on the non contrast study, while two of them (25%) reported calcifications. On MRI, most presented as non enhancing multi-cystic lesions, representing blood of different ages, and had multiple hemosiderin rings, giving characteristic “bubbles of blood” appearance. Although not specific, this pattern should prompt to consider cerebellar GCM in the differential diagnosis. The lack of contrast enhancement may be due to the slow perfusion of CMs in general. Edema or mass effect may also be present, mimicking neoplasms [9, 15].

These large lesions are most commonly seen in the pediatric age group which is known to have an increased risk of hemorrhage for CMs. Due to this high risk of bleeding, surgery is clearly recommended in children with infratentorial GCMs, even if clinically silent [15, 20]. Gross total resection of cerebellar GCM is the mainstay of treatment, especially if the involved region is non eloquent. Based on our review, complete surgical removal with full neurological recovery was reported in at least three (37.5%) of the cerebellar GCMs. The developmental venous anomaly commonly associated with a solitary CM and postulated to have a role in its pathogenesis is best left alone to avoid the development of a life-threatening venous infarct [10].

Conclusion

Given their size and location, cerebellar GCMs in children are symptomatic lesions that prompt immediate surgical treatment. These are rare lesions, which can radiologically and clinically mimic a tumor with bleed, having to be considered in the differential diagnosis of cerebellar neoplastic mass lesions. Cerebellar GCMs may be suspected in cases of large hemorrhagic cerebellar mass, with “bubbles of blood” multi-cystic appearance, surrounded by hemosiderin ring, fluid-fluid levels, and accompanying edema-mass effect. Careful radiological study can provide a preoperative diagnosis and facilitate appropriate surgical management, but its confirmation requires histopathological examination. Complete surgical removal should be attempted when possible, since low morbidity, good recovery, and a complete long-term cure can be offered.

References

Porter RW, Detwiler PW, Spetzler RF, Lawton MT, Baskin JJ, Derksen PT et al (1999) Cavernous malformations of the brainstem: experience with 100 patients. J Neurosurg 90(1):50–58

Moriarity JL, Clatterbuck RE, Rigamonti D (1999) The natural history of cavernous malformations. Neurosurg Clin N Am 10(3):411–417

Raychaudhuri R, Batjer HH, Awad IA (2005) Intracranial cavernous angioma: a practical review of clinical and biological aspects. Surg Neurol 63(4):319–328

Robinson JR, Awad IA, Little JR (1991) Natural history of the cavernous angioma. J Neurosurg 75(5):709–714

Mottolese C, Hermier M, Stan H, Jouvet A, Saint-Pierre G, Froment JC, Bret P, Lapras C (2001) Central nervous system cavernomas in the pediatric age group. Neurosurg Rev 24(2–3):55–71 discussion 72-3

Acciarri N, Galassi E, Giulioni M, Pozzati E, Grasso V, Palandri G, Badaloni F, Zucchelli M, Calbucci F (2009) Cavernous malformations of the central nervous system in the pediatric age group. Pediatr Neurosurg 45(2):81–104

Clatterbuck RE, Moriarity JL, Elmaci I, Lee RR, Breiter SN, Rigamonti D (2000) Dynamic nature of cavernous malformations: a prospective magnetic resonance imaging study with volumetric analysis. J Neurosurg 93(6):981–986

Kim DS, Park YG, Choi JU, Chung SS, Lee KC (1997) An analysis of the natural history of cavernous malformations. Surg Neurol 48(1):9–17 discussion 17-8

Kan P, Tubay M, Osborn A, Blaser S, Couldwell WT (2008) Radiographic features of tumefactive giant cavernous angiomas. Acta Neurochir 150(1):49–55

Thakar S, Furtado SV, Ghosal N, Hegde AS (2010) A peri-trigonal giant tumefactive cavernous malformation: case report and review of literature. Childs Nerv Syst 26(12):1819–1823

Dao I, Akhaddar A, El-Mostarchid B, Boucetta M (2012) Giant cerebral cavernoma: case report with literature review. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 17(1):69–73 Review

van Lindert EJ, Tan TC, Grotenhuis JA, Wesseling P (2007) Giant cavernous hemangiomas: report of three cases. Neurosurg Rev 30(1):83–92 discussion 92. Epub 2006 Sep 19

Jurkiewicz E, Marcinska B, Malczyk K, Grajkowska W, Daszkiewicz P, Roszkowski M (2013) Giant cerebellar cavernous malformation in 4-month-old boy. Case report and review of the literature. Neurol Neurochir Pol 47(6):596–600

Konovalov AN, Ozerov SS, Belousova OB, Shishkina LV, Ozerova VI, Khukhlaeva EA, Gorelyshev SK (2005) Giant cavernous malformation of the cerebellum in a baby. Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko 4:27–29

Ozgen B, Senocak E, Oguz KK, Soylemezoglu F, Akalan N (2011) Radiological features of childhood giant cavernous malformations. Neuroradiology 53(4):283–289

Mehmet A, Zafer K, Reyhan E, Hulusi E (2007) Giant cavernous angioma mimicking cerebellar neoplasm with major bleed: a case report. Tip Arastirmalari Dergisi 5(3):153–156

Lew SM (2010) Giant posterior fossa cavernous malformations in 2 infants with familial cerebral cavernomatosis: the case for early screening. Neurosurg Focus 29(3):E18

Hayashi T, Fukui M, Shyojima K, Utsunomiya H, Kawasaki K (1985) Giant cerebellar hemangioma in an infant. Childs Nerv Syst 1(4):230–233

Lawton MT, Vates GE, Quinones-Hinojosa A, McDonald WC, Marchuk DA, Young WL (2004) Giant infiltrative cavernous malformation: clinical presentation, intervention, and genetic analysis: case report. Neurosurgery 55(4):979–980

Corapçioğlu F, Akansel G, Gönüllü E, Yildiz K, Etuş V (2006) Fatal giant pediatric intracranial cavernous angioma. Turk J Pediatr 48(1):89–92

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure of funding received for this work

None.

Conflict of interest

There was no financial support nor industry affiliations involved in this work. None of the authors have any personal or institutional financial interest in drugs, materials, or devices.

Additional information

Previous presentation as a poster “XXXII Reunión de la Sociedad Española de Neurocirugía Pediátrica, Barcelona, Spain. February 2016.”

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Villaseñor-Ledezma, J., Budke, M., Alvarez-Salgado, JA. et al. Pediatric cerebellar giant cavernous malformation: case report and review of literature. Childs Nerv Syst 33, 2187–2191 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-017-3550-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-017-3550-7