Abstract

Objective

To explore the relationship between the consumption of coffee and tea with urolithiasis. We evaluated large epidemiological and small clinical studies to draw conclusions regarding their lithogenic risk.

Methods

A systematic review was performed using the Medline and Scopus databases, in concordance with the PRISMA statement. English, French, and Spanish language studies regarding the consumption of caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee and tea, and the relationship to urinary stone disease were reviewed. Case reports and letters, unpublished studies, posters, and comments were excluded.

Results

As per the inclusion criteria, 13 studies were included in the final review. Most studies, including four large prospective studies and one meta-analysis, reported a reduced risk of stone formation for coffee and tea. Caffeine has a diuretic effect and increases the urinary excretion of calcium, but if these losses are compensated for, moderate caffeine intakes may have little or no deleterious effects. Green and Herbal teas infused for short time had low oxalate content compared to black tea.

Conclusion

There is no evidence that moderate consumption of coffee raises the risk for stone formation in healthy individuals, provided the recommended daily fluid intake is maintained. The currently available literature supports in general a protective role for tea against the stone formation, mainly for green tea. However, heterogeneity of published data and lack of standardization needs to be addressed before final and clear conclusions can be given to patients and to the public in general.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nephrolithiasis is a complex disease with multiple genetic, dietary, and environmental factors that plays a role in its development and management. The estimated prevalence is around 14% in the industrialized world [1,2,3,4], however, this changes according to demographics and geographical areas studied. In the US for example, a history of stone disease is most common among older white males (10%), and lowest in younger black females (1%). The prevalence in Asians and Hispanics falls somewhere in between these two figures [2]. In addition, in recent decades a marked increase in renal stone prevalence has been noted, probably as a result of dietary habits and lifestyle [3].

A systematic metabolic evaluation is an essential part of the treatment and prevention of stone disease, which is estimated to be at least 40% without proper prevention [4, 5]. Diet consists of many important risk factors for urinary stone disease, and dietary modification is an inexpensive and safe method to prevent stone formation and stone recurrence [6].

The strict control of calcium, oxalate, fructose, salt, and protein consumption, monitoring fluid intake are all crucial components in the prevention of urinary stone formation, with most medical references promoting sufficient fluid intake for the production of at least 2–2.5 L of urine per day [7, 8]. In addition to drinking water, coffee and tea are among the beverages most widely consumed on a daily basis. Establishing the relationship between these two popular beverages and nephrolithiasis is met with confounding results.

In this systematic review, we have divided the paper into two separate parts for coffee and tea consumption, followed by a detailed discussion highlighting the possible mechanisms behind the results. Both these sections will also concentrate on the caffeine and oxalate content and their effect on the stone disease.

Material and methods

Evidence acquisition

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Studies in English, French and Spanish languages looking at the role of tea and coffee in kidney stone disease (KSD)

-

2.

Studies published from the inception of databases to March 2020.

-

3.

Adult patients

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Animal and laboratory studies

-

2.

Review articles, case reports, editorials, and grey literature

-

3.

Studies looking at lifestyle factors such as exercise, alcohol or smoking

Search strategy and study selection

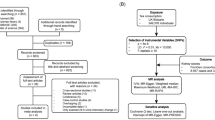

A systematic review was performed, using the Medline and Scopus databases. This review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Fig. 1). The keywords used were the followings: “Caffeine”, “coffee”, “tea”, “theophylline”, “black tea”, “green tea”, “methylxanthine”, “1-Methyluric acid”, “nephrolithiasis”, “urinary stones”, “risk”, “kidney stones” and “urolithiasis”. Search terms included a combination of keywords above and boolean operators (and, or) were used to augment the search. No time period restriction was set, and the search was carried out in March 2020. Two reviewers (YB, MC) identified all the studies independently and any discrepancies were resolved with mutual consensus. The main outcome of interest was the role of tea and coffee in the development of kidney stone disease. As a result of the heterogeneity of study outcomes, a narrative synthesis rather than a quantified meta-analysis of data was performed.

The Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) was implemented for quality appraisal [9].

Results

Of 4669 articles found through the initial database search, 125 abstracts were reviewed, 54 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility and 13 articles met the criteria for inclusion in the final review (Fig. 1). 23 animal-laboratory studies were excluded in addition to 18 review articles, case reports and editorials. Among the final 13 articles included, six prospective trials evaluated the relationship between both coffee and tea consumption and urinary stones, two studies evaluated coffee alone and five evaluated tea consumption and the risk for stone formation. Table 1 summarizes the most relevant studies found on this topic. The results are divided into two sections with the first section addressing coffee consumption and the second section focusing on tea consumption and the risk of KSD.

Coffee and the risk for nephrolithiasis

Large prospective studies reported a risk reduction for stone formation with the daily consumption of coffee and decaffeinated coffee [10,11,12,13,14]. More specifically, Curhan et al. found that the risk of stone formation in a large male population decreased by 10% for caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee with a 240 mL daily serving. This study also found a 14% risk reduction for tea consumption [10]. For the same intake amount, Curhan et al. presented in the Nurses’ Health study that the risk of stone formation decreased by 10% for caffeinated coffee, 9% for decaffeinated coffee, and 8% for tea [11]. Ferraro and Curhan reported a lower stone formation risk of 26% for caffeinated coffee, 16% for decaffeinated coffee, and 11% for tea [12]. Littlejohns et al. reported that for every additional 200 ml drink consumed per day, the risk of kidney stones declined by 13% [13]. This was primarily due to tea, coffee, and alcohol, however no association between water intake and kidney stone risk was found.

Ferraro and Curhan published another study in which a multivariate adjustment was done for age, BMI, fluid intake, and other factors [14]. The results showed that participants with the highest caffeine intake had a 26–31% lower risk of developing KSD in the three different cohorts studied. The association remained significant in the subgroup of participants with a low or no intake of caffeinated coffee in one cohort. In a subgroup analysis of 6033 participants with an available 24-h urinary composition, the intake of caffeine was associated with higher urine volume, calcium, and potassium and with lower urine oxalate and supersaturation for calcium oxalate and uric acid. These findings were also demonstrated in two other studies. Taylor et al. showed that participants in the highest quartiles’ caffeine intake excreted 10 mg/d more urinary calcium than participants in the lowest quartiles. The authors, therefore, concluded that the impact of caffeine was relatively small [15]. In the second study, Massey et al. studied the effects of caffeine on urinary composition in 39 calcium stone formers. The results showed that caffeine increased urinary calcium/creatinine (Ca/Cr), magnesium/Cr, citrate/Cr and sodium/Cr but not oxalate/Cr in stone formers and controls. The authors concluded that caffeine consumption may modestly increase the risk of calcium oxalate stone formation [16].

In an effort to overcome the limitation of genetic heterogeneity on the risk of urolithiasis from coffee consumption, Goldfarb et al. conducted a large male twin study to examine mainly the influence of genetic factors associated with KSD [17]. The participants were surveyed by questionnaires for their dietary habits and history of stone disease. The results showed a protective, dose–response pattern for the intake of five or more cups of coffee. Coffee drinkers were half as likely to develop kidney stones as those who did not drink coffee. The results also showed marginal protective effects for coffee consumption.

Worth mentioning, when presenting the results of these studies, is that other additional beverages were found to decrease the risk of stone formation. These were beer [10, 12, 18], wine [10,11,12], and orange juice [12]. Grapefruit juice [10, 11] and sugar-sweetened beverages [12] increased the risk for stone formation.

Based on our review and the reported work done by other authors including Curhan et al., Borghi et al., Friedlander and Pearle, Gambaro et al., Sorokin and Pearle, the findings suggest that the risk of KSD is reduced by the daily intake of both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee, and tea [19,20,21,22,23,24].

Tea and the risk for nephrolithiasis

Tea consumption was also shown to be protective in the large epidemiologic studies mentioned in the previous section [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Other studies that primarily focused on tea consumption also reveals a protective effect towards it [25,26,27,28]. Rode et al. studying the effects of green tea consumption in a population of hypercalciuric stone-formers found no difference between green tea drinkers and non-drinkers for stone risk factors. This was true for oxalate excretion in 24-h urine collections, but also for urine pH, calcium, urate, and citrate. While no evidence for increased oxalate-dependent stones was found in daily green tea drinkers, in female green tea drinkers no calcium oxalate monohydrate (COM) stone was detected at all [25]. Shu et al., showed that regular tea intake was associated with 13% and 22% lower risk of incidental KSD in women and men respectively compared to former tea drinker or someone who has never drunk tea [26].

Chen et al. went a step further and investigated the chronologic impact of tea consumption over time and whether it has an independent effect on the risk of stone formation. Their results showed that daily tea consumption ≥ 240 mL was related to a decreased risk of KSD [27]. Zhuo et al. did not show any significant effect related to the frequency of tea consumption and KSD. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis by tea-drinking habits, a preference for strong tea was suggested to be a protective factor of urolithiasis (OR 0.793) [28].

There were contradictory conclusions from Biao et al. [29]. In a retrospective study, the authors’ final conclusion was that tea consumption was independently associated with an increased risk of KSD and they suggested that a decrease in the consumption of tea as a preventive strategy for KSD. However, their study was flawed with many limitations including no specification of the category of tea despite the known variations in oxalate content of different types of tea.

Quality appraisal of studies

In general, the quality of evidence of included studies was intermediate, mainly due to selection biases of the study populations and recall biases associated with the use of questionnaires.

These limitations affected almost all the cohort studies of coffee and tea. In addition, there is a major lack of standardization in the medical research of tea and coffee consumption, concerning the type of beverage, studied and its preparation methods, both are factors that would influence the lithogenic risk. The average appraisal score using NOS was 5.23/9 (range 4–7) (Table 2). The areas of weakness across the studies included the selection and comparability categories, however, they were most notable regarding the method of outcome assessment.

Discussion

Despite a potential lithogenic role of caffeine [15, 16], data from big epidemiologic and clinical studies show that coffee paradoxically may have a protective effect against KSD [10,11,12,13,14]. A possible explanation of this apparent contradiction could be linked to the diuretic properties of caffeine and its effect on the adenosine receptors in the kidney which has previously been demonstrated in the animal models [30]. The overall result is an increase in urine flow and if adequately compensated by water intake, represents an important protective factor against the development of KSD. Moreover, coffee plants are a rich source of citric acid and hence its derivative citrate can also play a strong role in the inhibition of KSD. Lastly, the demonstration of a protective effect for decaffeinated coffee suggests that there might be a protective role for other bioactive compounds in coffee.

The protective effect of green tea is most likely due to the presence of polyphenol compounds called catechins [31]. These have been of major interest due to their antioxidant properties [32], and a possible role in the prevention of KSD [32,33,34,35]. Green tea contains the highest concentration of catechins when compared to black tea and hence considered more preventative against KSD.

In the studies included, decaffeinated coffee also had a protective role against stone formation [10,11,12,13,14]. This naturally could not be explained by a protective effect of caffeine alone. The main two arguments to explain this observation are the presence of small amounts of caffeine that might potentially play a role despite the decaffeination process and the presence of other protective bioactive compounds like trigonelline, which may exert similar protective effects like caffeine [36]. It is also important to note that despite the possible protective effects of caffeine against KSD, not every beverage containing caffeine might play a protective role. Some beverages like caffeine-containing soda also contain large quantities of sugar and might pose a serious risk for KSD.

Coffee should be consumed in moderation, and water intake must be maintained and should accompany it to dilute the potential effect of hypercalciuria. Similarly, it is important to maintain calcium intake with coffee to balance oxalate containing food and to reduce the risk of osteoporosis, which potentially might be the result of chronic caffeine-induced hypercalciuria [37].

This systematic review comprehensively summarizes the evidence for the effect of tea and coffee consumption and the risk of KSD. As with all systematic reviews, we acknowledge the publication bias and that there are limitations to the conclusions drawn, which are only as robust as the included articles. Another limitation of this systematic review is that most of the included studies are non-randomised studies with significant heterogeneity in study design and inconsistency of data reporting. A lack of standardised methods of data collection and reporting made it difficult to compare or combine the outcomes. Many confounding factors were not accounted for including the modifiable and non-modifiable factors (e.g., age, gender, race, and body mass index), in addition to the dietary factors (accompanying nutrition the participants consumed during the study periods).

Moreover, there is a potential publication and selection bias mainly for the large cohort studies of Curhan et al. and Ferraro et al., in addition to the significant overlap between the cohort groups of these studies.

Regarding tea intake, we found a lack of standardization relating to the tea type studied and its preparation methods, both factors that would change the oxalate level consumed among other lithogenic factors and presumably alter the risk posed for KSD. The consumption method itself e.g. the addition of milk or sugar can influence the risk for stone formation. Similarly, the important role of genetic polymorphism, that might affect the stone risk in relation to coffee and tea consumption was addressed in one only study [17].

All of these limitations impede the task of finding definitive recommendations for our patients and colleagues. Hence future studies need to include coffee and tea types being studied, their caffeine and oxalate contents, and the stone types for which the risk or benefit is being evaluated with standardised outcome measures and long-term follow-up.

Conclusion

Moderate coffee consumption does not increase the risk of KSD provided the recommended daily fluid intake is maintained. There seems to be a protective effect of tea consumption especially green tea towards KSD. However, there is currently a lack of standardised research regarding the preparation and consumption of tea. The heterogeneity of published data and lack of standardization needs to be addressed before final and clear conclusions can be given to patients and to the public in general.

References

Curhan GC (2007) Epidemiology of stone disease. Urol Clin North Am 34(3):287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2007.04.003

Stamatelou KK, Curhan GC (2003) Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States 1976–1994. See editorial by Goldfarb p.1951. Kidney Intern 63(5):1817–1823. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00917.x

Rukin NJ, Siddiqui ZA, Chedgy ECP, Somani BK (2017) Trends in upper tract stone disease in England: evidence from the hospital episodes statistics database. Urol Int 98(4):391–396

Letendre J, Cloutier J, Villa L et al (2015) Metabolic evaluation of urinary lithiasis: what urologists should know and do. World J Urol 33:171–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-014-1442-y

Daudon M, Jungers P, Bazin D, Williams JC (2018) Recurrence rates of urinary calculi according to stone composition and morphology. Urolithiasis. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-018-1043-0

Friedlander JI, Antonelli JA, Pearle MS (2015) Diet: from food to stone. World J Urol 33:179–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-014-1344-z

C. Türk, A. Skolarikos, K. Thomas EAU Guidelines. ISBN 978–94–92671–07–3. http://uroweb.org/guidelines/compilations-of-all-guidelines

Pearle M, Preminger G, Turk T, White JR AUA Guidelines on medical managament of kidney stones (2019). https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/kidney-stones-medical-mangement-guideline

Stang A (2010) Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 25(9):603–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z

Curhan GC, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Spiegelman D, Stampfer MJ (1996) Prospective study of beverage use and the risk of kidney stones. Am J Epidemiol 143:240–247

Curhan GC, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Stampfer MJ (1998) Beverage use and risk for kidney stones in women. Ann Intern Med 128:534–540

Ferraro PM, Taylor EN, Gambaro G, Curhan GC (2013) Soda and other beverages and the risk of kidney stones. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8:1389–1395

Littlejohns TJ, Turney BW (2019) Fluid intake and dietary factors and the risk of incident kidney stones in UK Biobank: a population-based prospective cohort study. Europ Urol Focus. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euf.2019.05.002

Ferraro PM, Taylor EN, Gambaro G, Curhan GC (2014) Caffeine intake and the risk of kidney stones. Am J Clin Nutr 100:1596–1603

Taylor EN, Curhan GC (2009) Demographic, dietary, and urinary factors and 24-h urinary calcium excretion. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4(12):1980–1987. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.02620409

Massey LK, Sutton RA (2004) Acute caffeine effects on urine composition and calcium kidney stone risk in calcium stone formers. J Urol 172(2):555–558

Goldfarb DS, Fischer ME, Keich Y, Goldberg J (2005) A twin study of genetic and dietary influences on nephrolithiasis: a report from the Vietnam Era Twin (VET) registry. Kidney Int 67(3):1053–1061

Shuster J, Dzegede S (1985) Primary liquid intake and urinary stone disease. J Chronic Dis 38(11):907–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(85)90126-2

Borghi L, Novarini A (1998) Urine volume: stone risk factor and preventive measure. Nephron 81(1):31–37. https://doi.org/10.1159/000046296

Friedlander JI, Antonelli JA, Pearle MS (2014) Diet: from food to stone. World J Urol 33(2):179–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-014-1344-z

Gambaro G, Trinchieri A (2016) Recent advances in managing and understanding nephrolithiasis/nephrocalcinosis. F1000Research. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.7126.1

Sorokin I, Pearle MS (2018) Medical therapy for nephrolithiasis: state of the art. Asian J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajur.2018.08.005

Heilberg IP, Goldfarb DS (2013) Optimum nutrition for kidney stone disease. Advanc Chronic Kidney Dis 20(2):165–174. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2012.12.001

Meschi T, Borghi L (2011) Lifestyle recommendations to reduce the risk of kidney stones. Urol Clin North Am 38(3):313–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2011.04.002

Rode J, Haymann J-P (2019) Daily green tea infusions in hypercalciuric renal stone patients: no evidence for increased stone risk factors or oxalate-dependent stones. Nutrients 11(2):256. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11020256

Shu X, Hsi RS (2018) Green tea intake and risk of incident kidney stones: prospective cohort studies in middle-aged and elderly Chinese individuals. Int J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1111/iju.13849

Chen H-Y, Yang Y-C (2018) Increased amount and duration of tea consumption may be associated with decreased risk of renal stone disease. World J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-018-2394-4

Zhuo D, Yao Y (2019) A study of diet and lifestyle and the risk of urolithiasis in 1, 519 patients in Southern China. Med Sci Monit 25:4217–4224. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.916703

WU Zhong Biao (2017) Tea consumption is associated with increased risk of kidney stones in Northern Chinese: a cross-sectional study. Biomed Environ Sci 30(12):922–926

Rieg T, Vallon V (2005) Requirement of intact adenosine A1 receptors for the diuretic and natriuretic action of the methylxanthines, theophylline and caffeine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 313(1):403–409

Nirumand MC, Bishayee A (2018) Review dietary plants for the prevention and management of kidney stones: preclinical and clinical evidence and molecular mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19030765

Henning SM, Niu Y, Lee NH, Thames GD, Minutti RR, Wang H, Go VLW, Heber D (2004) Bioavailability and antioxidant activity of tea flavanols after consumption of green tea, black tea, or a green tea extract supplement. Am J Clin Nutr 80:1558–1564

Kanlaya R, Thongboonkerd V (2019) Protective effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate from green tea in various kidney diseases. Adv Nutr 10:112–121

Jeong BC, Kim BS, Kim JI, Kim HH (2006) Effects of green tea on urinary stone formation in vivo and in vitro study. J Endourol 20:356–361

Itoh Y, Yasui T, Okada A, Tozawa K, Hayashi Y, Kohri K (2005) Preventive effects of green tea on renal stone formation and the role of oxidative stress in nephrolithiasis. J Urol 173:271–275

Arai K, Kodama S (2015) Simultaneous determination of trigonelline, caffeine, chlorogenic acid and their related compounds in instant coffee samples by HPLC using an acidic mobile phase containing octane sulfonate. Anal Sci 31(8):831–835. https://doi.org/10.2116/analsci.31.831

Massey LK, Whiting SJ (1993) Caffeine, urinary calcium, calcium metabolism and bone. J Nutrition 123(9):1611–1614. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/123.9.1611

Funding

This is an independent study and is not funded by any external body.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YB project development, data collection, manuscript writing. MC, SD data analysis, BK-S, OT project development, data collection, manuscript editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

This research is a review paper and does not involve research in humans or animals.

Disclosure

Prof. Olivier Traxer is a consultant for Coloplast, Rocamed, Olympus, EMS, Boston Scientific and IPG.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barghouthy, Y., Corrales, M., Doizi, S. et al. Tea and coffee consumption and the risk of urinary stones—a systematic review of the epidemiological data. World J Urol 39, 2895–2901 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-020-03561-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-020-03561-w