Abstract

We performed exome sequencing for mutation discovery of an ENU (N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea)-derived mouse model characterized by significant elevated plasma alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activities in female and male mutant mice, originally named BAP014 (bone screen alkaline phosphatase #14). We identified a novel loss-of-function mutation within the Fam46a (family with sequence similarity 46, member A) gene (NM_001160378.1:c.469G>T, NP_001153850.1:p.Glu157*). Heterozygous mice of this mouse line (renamed Fam46a E157*Mhda) had significantly high ALP activities and apparently no other differences in morphology compared to wild-type mice. In contrast, homozygous Fam46a E157*Mhda mice showed severe morphological and skeletal abnormalities including short stature along with limb, rib, pelvis, and skull deformities with minimal trabecular bone and reduced cortical bone thickness in long bones. ALP activities of homozygous mutants were almost two-fold higher than in heterozygous mice. Fam46a is weakly expressed in most adult and embryonic tissues with a strong expression in mineralized tissues as calvaria and femur. The FAM46A protein is computationally predicted as a new member of the superfamily of nucleotidyltransferase fold proteins, but little is known about its function. Fam46a E157*Mhda mice are the first mouse model for a mutation within the Fam46a gene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Skeletal dysplasias (osteochondrodysplasias) are a complex group of bone and cartilage disorders. More than 350 well-characterized skeletal dysplasias frequently associated with varying degrees of short stature are diagnosed based on radiographic, clinical, and molecular criteria. Many result from mutations in various gene families that encode extracellular matrix proteins, cellular transporters, signal transducers (ligands, receptors, and channel proteins), intracellular binding proteins, transcription factors, tumor suppressors, chaperones, enzymes, RNA processing molecules, cilia and cytoplasmic proteins, and a number of gene products of currently unknown function (for review see Krakow and Rimoin 2010).

FAM46A, formerly known as C6orf37 (Lagali et al. 2002), is a member of the evolutionarily conserved “family with sequence similarity 46.″ In mammals, this protein family consists of four members with little information about their biological roles: FAM46A, FAM46B, FAM46C, and FAM46D. FAM46C seems to enhance replication of some viruses in response to type I interferon (Schoggins et al. 2011). Antibodies against FAM46D were detected in plasma samples from patients with lung tumors and glioblastomas (Bettoni et al. 2009). The functions of FAM46B and FAM46D are unknown. Recently, FAM46B was described as kidney biomarker for refractory lupus nephritis (Benjachat et al. 2015). Mouse models are not available for any of the four known FAM46 family members, with preweaning lethality observed in Fam46c KO mice (www.mousephenotype.org).

FAM46A was first described as a novel candidate gene for a human retinal disease (Lagali et al. 2002). Comprehensive homology-based computational analysis identified FAM46A as a new member of the large and highly diverse superfamily of nucleotidyltransferase (NTase) fold proteins, which transfer nucleoside monophosphate (NMP) from nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) to a hydroxyl group of an acceptor molecule (Kuchta et al. 2009). Some NTases such as adenylate cyclases take part in the synthesis of intracellular second messenger from ATP (i.e., cAMP) and are crucial for cellular signaling (Aravind and Koonin 1999; Kuchta et al. 2009). FAM46A contains a domain of unknown function (DUF1693), weakly similar to prion-like-(q/n-rich)-domain-bearing protein 44, isoform d of Caenorhabditis elegans (Etokebe et al. 2009), and a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR)-encoded PS50315 domain, which are associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis (Etokebe et al. 2014) and to osteoarthritis of the hip- and knee-joints in humans (Etokebe et al. 2015). FAM46A is predicted to be a soluble, globular, cytosolic protein containing several potential phosphorylation sites (Lagali et al. 2002). In humans, FAM46A has been reported to possibly be a SMAD signaling pathway related protein as determined by a yeast two-hybrid screen (Colland et al. 2004; Etokebe et al. 2009), where SMADs are intercellular effectors of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) (Baker and Harland 1997). FAM46A is expressed in ameloblasts’ nuclei of tooth germs and might play an important role during development of mouse teeth (Etokebe et al. 2009). RNA in situ hybridization experiments showed Fam46a expression in mineralizing tissues as ribs, tibia, clavicle, mandible, and maxilla in mouse embryos (E14.5) (Diez-Roux et al. 2011).

We systematically screened N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-treated mice by phenotyping for morphological and blood-based parameters of bone homeostasis including total inorganic calcium (Ca), total inorganic phosphate (Pi), and total ALP activity (Sabrautzki et al. 2012). To identify the causative mutations, we applied whole exome sequencing.

Here, we describe the first dominant Fam46a mutant mouse model, Fam46a E157*Mhda. We characterized heterozygous (Fam46a E157*/+) and homozygous (Fam46a E157*/−) mice in comparison with wild-type littermates (Fam46a WT). Our data showed remarkable skeletal defects along with a dramatic elevation of serum ALP activities in Fam46a E157*/− mice. In addition to the expression of Fam46a early in development, we show here that Fam46a is also expressed in adult bone tissues, suggesting a role in bone formation and remodeling.

Materials and methods

Generation of mouse lines

ENU mutagenesis was performed on the pure inbred C3HeB/FeJ (C3H) mouse strain purchased originally from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) as described recently (Aigner et al. 2011; Sabrautzki et al. 2012). All experiments were approved by the ethics commission and the government of Upper Bavaria (reference numbers 55.2-1-54-2532-126-11). Animal husbandry followed the regulations of the directive 2010/63/EU. Briefly, 10- to 12-week-old male C3H mice (G0) were treated by three weekly injections of 90 mg/kg body weight ENU (Serva Electrophoresis, Heidelberg, Germany) and mated to wild-type C3H female mice. For the dominant screen, G0-derived litters (F1 mice) born at least 101 days after the last injection were examined according to a standardized in-house phenotyping protocol. Confirmed mutant lines were bred for at least five generations and archived by frozen sperm. Mouse lines are given internal lab codes until the mutation is identified and the official name is implemented. Fam46a E157*/+ and Fam46a E157*/− pups were obtained by heterozygous intercross or by mating heterozygous with homozygous mice. Thus, the mouse line BAP014 (bone screen alkaline phosphatase #14) was given the official international name Fam46aE157*Mhda including the Glu157* amino acid position, the type of mutation, and Mhda (Martin Hrabě de Angelis) as the producer of the mouse line.

Phenotyping

Clinical–chemical analysis

Blood was sampled in anesthetized mice by puncture of the retro-orbital sinus at the age of 12, 24, 36, and 52 weeks. Plasma samples were analyzed using an Olympus AU400 autoanalyzer (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) and adapted test kits (Klempt et al. 2006) for ALP activity, Ca, Pi, total protein, albumin, creatinine, urea, uric acid, cholesterol, triglycerides, and glucose levels. Statistical differences (p values) of alterations of values between all tested affected mice and non-affected littermates were assessed separately for males and females by t test giving mean ± standard deviation (SD) using SigmaStat 3.5. software (Systat Software Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

X-ray and bone morphometry

X-ray was performed using a Faxitron MX-20 Cabinet X-ray System (Faxitron Bioptics, LLC, Tucson, AZ, USA). Micro-CT measurements were conducted by a SkyScan 1176 in vivo micro-CT (Bruker, N.V., Kontich, Belgium). Both analyses were performed in the Dysmorphology module of the German Mouse Clinic (Fuchs et al. 2011).

Alizarin Red/Alcian Blue staining

From a 25-week-old Fam46a E157*/− mouse and a Fam46a WT littermate skin, organs, and muscles were removed. The prepared skeletons were dehydrated and fixed in 100 % ethanol. Alizarin Red/Alcian Blue staining of the skeleton was performed as described previously (Inouye 1976).

Skeletal analysis

Femora of 32- to 35-week-old Fam46a WT, Fam46a E157*/+, and Fam46a E157*/− mice were fixed in 5 % formalin (pH 7.4) for 2 days, rinsed with water, and decalcified for 4 weeks rotating in 20 % EDTA (pH 7.4), and the solution was changed every 4–5 days. The decalcified bones were rinsed with water for 2 h, dehydrated in ethanol series (50, 70, 90, 96 %), isopropanol, and xylene, and then embedded in paraffin. Longitudinal sections (5 µm) were transferred on slides; paraffin was removed by incubation in xylene and a descending series of ethanol (95, 70, 50 %) and finally rinsed with water. Staining of collagen was performed with azan trichrome (Heidenhain) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich, Schnelldorf, Germany). The sections were analyzed with an Axioskop 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss Jena, Jena, Germany) using software AxioVision Rel 4.8.

Exome sequencing

Capture and sequencing of murine exomes

We performed in-solution targeted enrichment of exonic sequences from one mouse of the mutant mouse line and one control mouse (C3HeB/FeJ) by using the SureSelectXT Mouse All Exon 50 Mb kit from Agilent (Santa Clara, CA, USA). The generated libraries were indexed, pooled, and sequenced as 100 bp paired-end runs on a HiSeq2000 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Mapping and variant calling

Read alignment to the mouse genome assembly mm9 was done with Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (BWA, version 0.5.9) and yielded 8.72 and 9.2 Gb of mapped sequence data corresponding to an average coverage of 103× and 112× for the mutant and control, respectively (Supplemental Table 1). Single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions and deletions (indels) were detected with SAMtools (version 0.1.7). SNVs were only lightly filtered on SNV quality score (SNV quality >40), because we preferred false positives to negatives. After subtracting variants from the control, from dbSNP128, and from 120 other mice in our in-house database, 40 unique coding variants specific to the mutant mouse line remained (Supplemental Table 2).

Validation of candidate variants by capillary Sanger sequencing

Candidate SNVs were validated by amplifying DNA of mutant and control mice with intronic primers. Bidirectional Sanger sequencing was then performed using the ABI BigDye Terminator v.3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Primer sequences (available on request) were determined with the ExonPrimer software (http://ihg.helmholtz-muenchen.de/ihg/ExonPrimer.html). Segregation of the genotype with the phenotype was analyzed.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR of Fam46a in bone

Total RNA was extracted from murine calvaria and femur using Trizol reagent (Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA (500 ng) using the SuperScript III First-strand Synthesis SuperMix (Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. First-strand cDNA (1 µl) was used as template to perform a multiplex PCR (25 µl) using the Advantage cDNA PCR Kit (Clontech Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan). cDNAs of other mouse tissues (mouse embryo 17d, liver, kidney, and heart) were purchased (Marathon-ready cDNA, Clontech Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan). We investigated the expression of Fam46a and G3pdh simultaneously in 6 different murine tissues using the following PCR conditions (touchdown PCR): 94 °C for 1 min, 94 °C for 30 s, 65 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 1 min, −1 °C for each of the next 7 cycles; 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 1 min during 25 cycles; and a final extension of 68 °C for 5 min. Primers used for Fam46a were Fam46a_Cex2_F1 (5′-CTACAAGGACCTGGACCTCATC-3′) and Fam46a_Cex3_R1 (5′-TCTACACTGAATTCAAACTGCCTC-3′).

Results

Phenotypic identification of a new ENU-derived mouse model BAP014

In a screen of F1 ENU-mutagenized mice, we identified a trait, designated BAP014, with significantly elevated plasma total ALP activities (Sabrautzki et al. 2012). At this point, the underlying mutation was still unknown. When analyzed at 12, 24, and 36 weeks of age, phenotypically mutant BAP014 mice displayed significantly higher ALP activities compared to wild-type mice (Table 1), while plasma total Ca and Pi values remained normal (data not shown). At 52 weeks of age ALP activity of female and male BAP014 mice showed no significant difference to wild-type values (Table 1). BAP014 mice appeared morphologically normal with no visible phenotype.

Exome sequencing identifies a Fam46a nonsense mutation

We performed exome sequencing using in-solution targeted enrichment of exonic sequences and massively parallel sequencing to identify the gene mutation of the BAP014 mouse line (Supplemental Table 1). To search for the causative variants, we compared the sequence of one BAP014 mouse with the sequence of one mouse from the background strain (C3HeB/FeJ).

By comparing the sequencing data with the published reference sequence (UCSC Genome Browser, NCBI37/mm9), we detected a total of ~124,900 single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions and deletions (indels) per mouse sample. SNVs were filtered step by step to remove variants found in both wild-type and mutant sequence, and then to remove variants known to be present in the database of short genetic variations (dbSNP128) and within 120 in-house generated mouse exomes. Subsequently, SNVs were filtered on the basis of technical quality criteria (SNV quality >40, mapping quality >50). This resulted in 40 SNVs unique for the BAP014 mouse line. Finally, we applied filters for the type and consequence of the SNVs (missense, nonsense, stoploss, splice, frameshift, indel). We obtained 12 candidate SNVs and one indel which fulfilled these criteria (Supplemental Table 2). Linkage analysis using SNP genotyping of 35 heterozygous and 26 wild-type littermate BAP014 mice was performed previously and revealed a candidate linkage region with a highest Chi-square of 18.46 on mouse chromosome 9 between the markers rs3023207 and rs3673055 (mm9_chr9:37,503,221–96,233,485, size 58.7 Mb) (Sabrautzki et al. 2012). Only one candidate SNV was located within the candidate linkage interval on mouse chromosome 9. Although linkage data were available, we decided to analyze all 13 variants of interest within a cohort of 8 phenotypically wild-type and 8 phenotypically mutant mice by capillary sequencing. Only the linked SNV on mouse chromosome 9 segregated in all mutant mice analyzed. This unique SNV was a heterozygous nonsense mutation within the Fam46a gene leading to a premature stop codon after 156 amino acids (NM_001160378.1:c.469G>T, NP_001153850.1:p.Glu157*) (Fig. 1). Thus, the BAP014 mouse line was renamed Fam46a E157*Mhda. Comparison of this position (mm9_chr9:85,219,964) with published resequencing data of 18 different mouse strains (Ensemble Genome Browser 72: Mus musculus) revealed that the nucleotide change found in Fam46a E157*Mhda mice was unique to this mouse mutant and not found in other mouse strains.

Identification of a nonsense mutation in Fam46a by exome sequencing. Exome sequencing revealed a heterozygous nonsense mutation (NM_001160378.1:c.469G>T, NP_001153850.1:p.Glu157*) within the Fam46a (family with sequence similarity 46, member A) gene leading to a premature termination of translation. a Exome sequencing data are visualized with IGV (Integrative Genomics Viewer (Robinson et al. 2011)). In total, 122 reads were mapped successfully to Fam46a using BWA (Burrows-Wheeler alignment tool) covering the nonsense mutation at genomic position mm9_chr9:85,219,964. Fam46a is located on the minus strand. 58 reads (47.5 %) covered the complementary C reference allele, while 63 reads (51.6 %) covered the complementary mutant A allele. b Confirmation of the nonsense mutation (marked by an asterisk) in Fam46a E157*/+ and Fam46a WT mouse DNA samples by capillary Sanger sequencing

Generation of homozygous Fam46a E157* mice and morphology

To further investigate the functional consequence of the nonsense mutation, we performed heterozygote intercross mating to generate homozygous Fam46a E157* mice. Thirty-nine heterozygote intercross matings yielded 55 wild-type, 109 heterozygous, and 20 homozygous Fam46a E157* mice. The observed low number of homozygous mice, showing an abnormal Mendelian ratio, may reflect lethality of Fam46a E157*/− mice.

Surviving Fam46a E157*/− mice showed phenotypic abnormalities with variable penetrance. At the age of 12 weeks, mean ALP values in male Fam46a E157*/− mice (n = 5; mean 361 ± 41.3 U/l) were twice as high as in heterozygous male mice (n = 28; 159 ± 11 U/l) (Fig. 2). In 2 homozygous female mice, 419 ± 18.3 and 352 ± 10.4 U/l mean ALP values were measured compared to 218 ± 20 U/l in 19 heterozygous 12-week-old mice (Fig. 2).

ALP activities of Fam46a WT, Fam46a E157*/+, and Fam46a E157*/− mice. ALP activities [U/l] of 12-week-old mice were measured. When compared to Fam46a WT mice, ALP activities of homozygous and heterozygous mutant mice were significantly increased in female and male mice. Significance was determined with the 2-sided Mann–Whitney U test (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001)

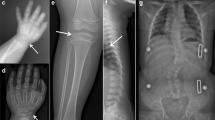

Fam46a E157*/− mice showed distinct morphological skeletal and growth phenotypes. All Fam46a E157*/− mice had significantly reduced body size (proportionate short stature) compared to Fam46a WT and heterozygous littermates (Figs. 3a, 4a). Fam46a E157*/− mice displayed an abnormal gait due to shortened and twisted front and/or hind limbs with variable severity. In one severely affected 22-week-old male Fam46a E157*/− mouse, the talocalcaneal joint of the left hind limb appeared thickened and reddened (Fig. 3b). At the right hind limb, the femur appeared shortened and the talocalcaneal joint appeared abnormally twisted (Fig. 3c). X-ray analysis revealed that the right femur was shortened, thickened, and also showed an abnormal morphology (Fig. 3d). Both humeral bones appeared with similar malformations and the thoracic vertebral column was distorted (Fig. 3d). Micro-CT scans showed profound abnormalities of long bones, joints, ribs, and vertebrae. The thickening of the left talocalcaneal joint became more distinct as an obvious malformation of the distal tibia (Fig. 3e). The right femur was shortened and highly malformed, possibly due to a healed fracture. The right talocalcaneal joint calcaneum was shortened, malformed, and embedded in a hypertrophic mass of unknown tissue (Fig. 3f, g). Malformation of the left humerus appeared at the region of the deltoid tuberosity (Fig. 3h). Comparison of whole skeleton preparations of a Fam46a WT and another Fam46a E157*/− mouse showed shortened and severely malformed ribs with calluses, compression of the rib cage, abnormal scapulae, and a left shortened and thickened humerus (Fig. 3i, j).

Phenotypic appearance of Fam46a E157*/− mice. 22-week-old Fam46a E157*/− mice showed a distinct phenotype with significantly reduced body size (short stature), abnormal limbs, and bone phenotypes. a When compared to a Fam46a WT littermate, the homozygous mutant had a reduced body size. b The talocalcaneal joint of the left hind limb appeared thickened and reddened. c At the right hind limb, shortening of the femur was present with an abnormal twisted talocalcaneal joint. d X-ray analysis confirmed the hind limb abnormalities and showed in addition thickened humeral bones and a distorted thoracic vertebral column (black arrows). e–h We performed SkyScan analysis of this Fam46a E157*/− mouse. e The thickening of the left talocalcaneal was identified to be more likely a malformation of the distal tibia. f The right femur was shortened and seemed to be twisted possibly due to a fracture. The calcaneum in the right talocalcaneal joint was shortened, malformed, and appeared to be embedded in a hypertrophic mass of unknown tissue. g These findings were also observed in the craniodorsal scan view. h Thickening of the left humerus of the Fam46a E157*/− mouse was detected at the region of the deltoid tuberosity (arrow). i, j Images of total mouse skeletons showed shortened and severely malformed ribs with calluses, compression of the rib cage, abnormal scapulae, and a left shortened and thickened humerus in another Fam46a E157*/− mouse not to be seen in the Fam46a WT (white arrows). L left, R right

Alizarin Red/Alcian Blue staining of the skeleton in 25-week-old Fam46a E157*/− mice. a Alizarin Red/Alcian Blue staining of the whole skeletons revealed a possible delayed ossification within the mouse tail, snout, and pelvis shown by the extensive blue staining of the cartilage (black arrows). b The Fam46a E157*/− mouse had a smaller skull with a very thin parchment-like calvaria (upper picture). c, d The scapula and ischium bones showed smaller size and abnormal shapes in the Fam46a E157*/− mouse (left Fam46a E157*/−, right Fam46a WT, black arrows). e The humeri showed malformations like thickening and twisting in the Fam46a E157*/− mouse (left Fam46a E157*/−, right Fam46a WT, black arrows). f Magnification of a possible delay in ossification within the mouse tail (left Fam46a E157*/−, right Fam46a WT, black arrows)

Alizarin Red/Alcian Blue staining of the skeleton in Fam46a E157*/− mice

The Alizarin Red/Alcian Blue staining of the skeletons of 25-week-old Fam46a WT and Fam46a E157*/− mice revealed a delayed ossification within the mouse tail, snout, and pelvis (Fig. 4a, f, d). Fam46a E157*/− mice had smaller skulls with very thin probably hypomineralized calvaria showing severe defects in intramembranous ossification (Fig. 4b). The scapula and ischium bones showed smaller size and abnormal shapes in the Fam46a E157*/− mouse (Fig. 4c, d). In this Fam46a E157*/− mouse, mainly the humeri showed malformations like thickening and twisting of the long bones possibly resulting from defects in endochondral ossification (Fig. 4e).

Analysis of long bones in Fam46a E157* mice

Azan staining of femora of 32- to 35-week-old Fam46a WT and Fam46a E157*/+ mice showed normal trabeculae in both epiphyseal and metaphyseal regions of the growth plate, while in Fam46a E157*/− mice trabeculae are almost completely missing (Fig. 5a–c, g–i). The architecture of the growth plate was regular in all three groups, a trend towards an enlargement of this region can be observed in Fam46a E157*/− mice (Fig. 5d–f). Femurs of Fam46a E157*/− mice showed reduced length of the femur consistent with the general short stature of these mice. The cortical bone thickness of Fam46a E157*/− mice is proportionally reduced (Fig. 5l), whereas in Fam46a E157*/+ mice cortical bone thickness is unchanged or even slightly enhanced (Fig. 5k). Preparation of femoral bones of Fam46a E157*/− mice was hampered by the fragility of these bones and by multiple spontaneous fractures with developing callus.

Qualitative analysis of the structure of the femoral growth plate and adjacent trabecular bone. Femora of 32- to 35-week-old Fam46a WT, Fam46a E157*/+, and Fam46a E157*/− mice were fixed and stained with azan (Heidenhain). The structure of the metaphysis and diaphysis in the trochanteric region of the femur is depicted. Trabeculae (white arrows) of Fam46a WT and Fam46a E157*/+ mice both in the proximal and distal segments of the growth plate (GP) appear to be quite normal, while in Fam46a E157*/− mice trabeculae are almost completely missing (a–c proximal region, g–i distal region). The architecture of the growth plates is regular in all groups. There is a trend towards enlargement in homozygous mice (f). Cortical bone thickness is unchanged or slightly enhanced in heterozygous compared to control mice (j, k), while in homozygous mutants cortical thickness is reduced (l)

Expression of Fam46a in bone tissue

Fam46a expression in adult bone tissue has not been described yet. We isolated total RNA from whole femur and from calvaria of adult mice and performed semiquantitative multiplex RT-PCR experiments. Specific RT-PCR products were generated from adult control tissues (liver, kidney, and heart), mouse embryo 17 day, as well as from calcified tissues. Compared with the expression level of the housekeeping gene G3pdh (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase), Fam46a showed a strong expression in calvaria and femur (Fig. 6) suggesting a possible role in postnatal bone homeostasis.

Expression analysis of Fam46a in different mouse tissues. Expression analysis of Fam46a was performed using semiquantitative multiplex RT-PCR using Fam46a and G3pdh (Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) primers within the same reaction. Expression of Fam46a in bone tissue was analyzed in comparison to the expression in other embryonic and adult mouse tissues

Discussion

Using exome sequencing, we identified the gene mutated in an ENU-derived mouse model showing elevated ALP activity. Several observations substantiate the causal role of the Fam46a mutation within this mouse line. First, we identified a heterozygous Fam46a nonsense mutation in the exome data of the mutant mouse not present in the C3HeB/FeJ wild-type mouse and in 18 other mouse strains. Second, Fam46a is located within the candidate linkage interval of the mutant mouse line on mouse chromosome 9 (mm9_chr9:37,503,221–96,233,485, size 58.7 Mb). Third, we found segregation of the phenotype with the corresponding genotype in a mouse cohort of 8 phenotypical mutant and 8 wild-type littermate mice. Fourth, the mutation type identified (NM_001160378.1:c.469G>T, NP_001153850.1:p.Glu157*) is predicted to result in a truncation and a consequential loss-of-function of the Fam46a protein. Fifth, homozygous Fam46a E157* mice had greater ALP elevations and showed severe skeletal phenotypes.

In comparison to Fam46a E157*/+ mice with elevated ALP activities but no observed skeletal abnormalities, Fam46a E157*/− mice showed profound skeletal phenotypes and ALP activity values two-fold higher than heterozygous mice. ALP is a bone formation marker expressed early in development in bone (Rosati et al. 1994; Seibel 2005). Long bone malformations observed in surviving Fam46a E157*/− mice likely appear early in development. Whether Fam46a would affect embryonic development is unknown, although embryonic expression of Fam46a was shown (Etokebe et al. 2009). Non-surviving mice might have serious skeletal defects or non-skeletal abnormalities incompatible with life. Further analyses of mouse embryos are necessary to elucidate the specific role of Fam46a in embryonic development and early bone formation.

The human FAM46A transcript is weakly expressed in most adult tissues, e.g., skeletal muscle, thymus, liver, lung, and brain, but seems to be prominently expressed in fetal tissues, e.g., fetal liver, lung, and brain (Lagali et al. 2002). Fam46a is expressed in developing mouse tooth buds (Etokebe et al. 2009) suggesting a developmental role of Fam46a in some tissues including calcified tissues. Nevertheless, we did not observe any visible tooth abnormalities in Fam46a E157* mice. We showed that Fam46a is expressed in bone tissue, femur and calvaria, of adult mice suggesting a role in adult bone turnover. Interestingly, in Fam46a E157*/− mice distinct abnormalities were found in bones formed by both endochondral ossification as in femurs and humeri (Figs. 3g, h, j, 4e), and intramembranous ossification, including calvaria (Fig. 4b). We identified in Fam46a E157*/− mice fractures of the femur (Fig. 3f) and humerus (data not shown) and rib calluses (Fig. 4j) but we did not determine bone breaking strength. Interestingly, the analysis of bone structure showed normal femoral growth plates in Fam46a E157*/− mice (Fig. 5f) but minimal trabecular bone adjacent to the growth plate (Fig. 5c, i) as well as reduced cortical bone at the diaphysis (Fig. 5j).

Little is known about the function of FAM46A. In silico studies have shown that FAM46A may function as NTase fold protein (Kuchta et al. 2009). In humans, FAM46A is a SMAD signaling pathway related protein probably involved in TGF-β signaling (Barragan et al. 2008). Therefore, FAM46A might be involved in the TGF-β signal transduction, which is known to play important roles during development in processes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation (Chen et al. 2012). The importance of TGF-β1 in bone development and homeostasis has been extensively illustrated both in vitro and in vivo (Janssens et al. 2005). In humans, mutations within the TGF-ß/SMAD pathway are associated with skeletal dysplasias. For instance, domain-specific heterozygous mutations within the TGFB1 gene were identified as the cause of Camurati–Engelmann disease (OMIM #131300), a rare dominant type of skeletal dysplasia characterized by cortical thickening of the diaphysis of the long bones (Kinoshita et al. 2000). Whether FAM46A has a regulatory role in TGF-ß signaling during osteoblast development and/or ossification is unknown. Surviving Fam46a E157*/− mice clearly showed short stature, reduced bone strength, abnormal shape and structure of bones displaying hallmarks of skeletal dysplasias.

By comparing the syntenic chromosomal regions between mice and humans, FAM46A was located within a susceptibility locus for split-hand/foot malformation with long-bone deficiency (SHFLD) on human chromosome 6q14.1 (Naveed et al. 2007). SHFLD (SHFLD1 OMIM %119100, SHFLD2 OMIM %610685, SHFLD3 OMIM #612576) is a rare, severe limb deformity characterized by tibia aplasia with split-hand/split-foot deformity. Surviving Fam46a E157*/− mice showed severe unilateral or bilateral limb deformities but without tibia aplasia and split-hand/split-foot deformity. As occurs in SHFLD patients, Fam46a E157*/− mice showed numerous distinct dysplasia in affected long bones. No long bone was missing in surviving Fam46a E157*/− mice but non-surviving mice might have skeletal defects similar to those in SHFLD2 patients. Further studies are necessary to address this point.

The Fam46a E157*Mhda mutant mouse line having short stature with limb, long bone, ribs, and skull deformities, as well as missing trabeculae and reduced cortical thickness, is the first mouse model for a mutation within the Fam46a gene. FAM46A might be involved in embryonic development and bone formation but further studies to unravel this issue and the role in the pathophysiology of skeletal dysplasia are necessary.

References

Aigner B, Rathkolb B, Klempt M, Wagner S, Michel D et al (2011) Generation of N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced mouse mutants with deviations in hematological parameters. Mamm Genome 22:495–505

Aravind L, Koonin EV (1999) DNA polymerase beta-like nucleotidyltransferase superfamily: identification of three new families, classification and evolutionary history. Nucleic Acids Res 27:1609–1618

Baker JC, Harland RM (1997) From receptor to nucleus: the Smad pathway. Curr Opin Genet Dev 7:467–473

Barragan I, Borrego S, Abd El-Aziz MM, El-Ashry MF, Abu-Safieh L et al (2008) Genetic analysis of FAM46A in Spanish families with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa: characterisation of novel VNTRs. Ann Hum Genet 72:26–34

Benjachat T, Tongyoo P, Tantivitayakul P, Somparn P, Hirankarn N et al (2015) Biomarkers for refractory lupus nephritis: a microarray study of kidney tissue. Int J Mol Sci 16:14276–14290

Bettoni F, Filho FC, Grosso DM, Galante PA, Parmigiani RB et al (2009) Identification of FAM46D as a novel cancer/testis antigen using EST data and serological analysis. Genomics 94:153–160

Chen G, Deng C, Li YP (2012) TGF-beta and BMP signaling in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Int J Biol Sci 8:272–288

Colland F, Jacq X, Trouplin V, Mougin C, Groizeleau C et al (2004) Functional proteomics mapping of a human signaling pathway. Genome Res 14:1324–1332

Diez-Roux G, Banfi S, Sultan M, Geffers L, Anand S et al (2011) A high-resolution anatomical atlas of the transcriptome in the mouse embryo. PLoS Biol 9:e1000582

Etokebe GE, Kuchler AM, Haraldsen G, Landin M, Osmundsen H et al (2009) Family-with-sequence-similarity-46, member A (Fam46a) gene is expressed in developing tooth buds. Arch Oral Biol 54:1002–1007

Etokebe GE, Bulat-Kardum L, Munthe LA, Balen S, Dembic Z (2014) Association of variable number of tandem repeats in the coding region of the FAM46A gene, FAM46A rs11040 SNP and BAG6 rs3117582 SNP with susceptibility to tuberculosis. PLoS One 9:e91385

Etokebe GE, Jotanovic Z, Mihelic R, Mulac-Jericevic B, Nikolic T et al (2015) Susceptibility to large-joint osteoarthritis (hip and knee) is associated with BAG6 rs3117582 SNP and the VNTR polymorphism in the second exon of the FAM46A gene on chromosome 6. J Orthop Res 33:56–62

Fuchs H, Gailus-Durner V, Adler T, Aguilar-Pimentel JA, Becker L et al (2011) Mouse phenotyping. Methods 53:120–135

Inouye M (1976) Differential staining of cartilage and bone in fetal mouse skeleton by Alcian Blue and Alizarin Red S. Congen Anom 16:171–173

Janssens K, ten Dijke P, Janssens S, Van Hul W (2005) Transforming growth factor-beta1 to the bone. Endocr Rev 26:743–774

Kinoshita A, Saito T, Tomita H, Makita Y, Yoshida K et al (2000) Domain-specific mutations in TGFB1 result in Camurati-Engelmann disease. Nat Genet 26:19–20

Klempt M, Rathkolb B, Fuchs E, de Angelis MH, Wolf E et al (2006) Genotype-specific environmental impact on the variance of blood values in inbred and F1 hybrid mice. Mamm Genome 17:93–102

Krakow D, Rimoin DL (2010) The skeletal dysplasias. Genet Med 12:327–341

Kuchta K, Knizewski L, Wyrwicz LS, Rychlewski L, Ginalski K (2009) Comprehensive classification of nucleotidyltransferase fold proteins: identification of novel families and their representatives in human. Nucleic Acids Res 37:7701–7714

Lagali PS, Kakuk LE, Griesinger IB, Wong PW, Ayyagari R (2002) Identification and characterization of C6orf37, a novel candidate human retinal disease gene on chromosome 6q14. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 293:356–365

Naveed M, Nath SK, Gaines M, Al-Ali MT, Al-Khaja N et al (2007) Genomewide linkage scan for split-hand/foot malformation with long-bone deficiency in a large Arab family identifies two novel susceptibility loci on chromosomes 1q42.2-q43 and 6q14.1. Am J Hum Genet 80:105–111

Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES et al (2011) Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol 29:24–26

Rosati R, Horan GS, Pinero GJ, Garofalo S, Keene DR et al (1994) Normal long bone growth and development in type X collagen-null mice. Nat Genet 8:129–135

Sabrautzki S, Rubio-Aliaga I, Hans W, Fuchs H, Rathkolb B et al (2012) New mouse models for metabolic bone diseases generated by genome-wide ENU mutagenesis. Mamm Genome 23:416–430

Schoggins JW, Wilson SJ, Panis M, Murphy MY, Jones CT et al (2011) A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 472:481–485

Seibel MJ (2005) Biochemical markers of bone turnover: part I: biochemistry and variability. Clin Biochem Rev 26:97–122

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandy Lösecke, Sandra Hoffmann, Andreas Mayer, Carola Fischer, Bianca Schmick, Sören Kundt, Anja Wohlbier, Elfi Holupirek, Sebastian Kaidel, Silvia Crowley, and Gerlinde Bergter for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Robert Brommage for scientific discussions and revision of the manuscript. This work was supported by the German Ministry of Education and Research BMBF OSTEOPATH Grant (01EC1006B), Nationales Genomforschungsnetz (NGFN 01GR0430), and NGFNplus Grants (01GS0850 and 01GS0851).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Susanne Diener, Sieglinde Bayer, and Sibylle Sabrautzki have contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Diener, S., Bayer, S., Sabrautzki, S. et al. Exome sequencing identifies a nonsense mutation in Fam46a associated with bone abnormalities in a new mouse model for skeletal dysplasia. Mamm Genome 27, 111–121 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00335-016-9619-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00335-016-9619-x