Abstract

Biological invasions are a major threat to the terrestrial ecosystems of the sub-Antarctic islands. While non-native plants generally have negative impacts on native arthropods, few studies have investigated how both native and non-native arthropods and plants interact in the sub-Antarctic islands. This was the aim of our study, which was conducted on three islands of the Kerguelen archipelago. The design was based on the spatial proximity of areas dominated by non-native or native plant species. Trait-based indices were calculated to characterize the functional structure of plant communities, considering plant stature and leaf traits. Native and non-native vegetation had contrasting functional composition but their functional diversity was similar. The effects of the type of vegetation, native or non-native, and plant functional diversity on arthropods were tested. Native macro-arthropod richness and abundance were similar or higher in non-native vegetation, and benefited from greater plant functional diversity. Abundances of macro-herbivores, macro-decomposers and macro-predators were also similar or higher in non-native vegetation. Conversely, the abundances of micro-arthropods, Symphypleona springtails and Oribatida mites, were higher in native vegetation but we also found that plant functional diversity had a negative effect on Symphypleona. Our results suggest that non-native plants can affect micro-arthropods directly or indirectly, likely through their effects on abiotic factors. By affecting macro-arthropod abundances across different trophic groups and by depleting micro-arthropods, non-native plants can alter trophic interactions, functional balances and the functioning of whole ecosystem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

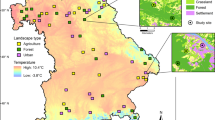

The Kerguelen Islands are located in the South Indian Ocean, and include a main island of 6675 km2 and about sixty other islands (1–200 km2) (Fig. 1). Like the other sub-Antarctic islands, their terrestrial ecosystems are characterized by strong geographical and historical isolation. They harbor a small number of sub-Antarctic species for both flora and fauna due to low levels of immigration from nearby continents and harsh environmental conditions (Chown et al. 1998). Terrestrial ecosystems are very simple, natively lacking some taxonomic groups such as mammals, amphibians and reptiles. Low plant diversity at the species and botanical family levels characterizes the native flora, which is composed of 29 species of vascular plants (Frenot et al. 2001). Native macro-arthropod communities are composed of 22 native insect species and two native spider species (Hullé and Vernon 2021), while micro-arthropod communities which are dominated by Oribatida mites and springtails are respectively composed of 24 and 18 native species (Deharveng and Travé 1981). It should be noted that micro-arthropod diversity may be underestimated and that some ‘undiscovered’ or cryptic species are likely to be found using recent advances in molecular biology in Antarctic (Collins et al. 2020). Macro-arthropod communities are unbalanced, some trophic groups being absent or not abundant such as herbivores or pollinators, and decomposers such as flies dominate macro-arthropod communities due to the large amounts of marine mammal and seabird excretions (Chown and Convey 2016). Despite the geographical isolation of the Kerguelen Islands, many species among plants, arthropods and mammals have been introduced, voluntarily or involuntarily, due to human activities, and have established. For instance, there are currently as many non-native as native macro-arthropod species (Hullé and Vernon 2021), while few non-native micro-arthropod species have been recorded (Deharveng and Travé 1981; Greenslade and Convey 2012). For plants, the number of species in some sites historically frequented by humans has become three times greater than the number of native species (Frenot et al. 2005), having potentially important impacts on ecosystem processes.

Biological invasions are widely recognized as being one of the most significant threats to biodiversity and are expected to increase with global warming (Shaw et al. 2010; McGeoch et al. 2015). Sub-Antarctic islands are deeply affected by climate change (Lebouvier et al. 2011) which makes their ecosystems more suitable to less stress-adapted non-native species (Pertierra et al. 2017). In addition, some established non-native species may become invasive (Frenot et al. 2005), exacerbating their impact on biodiversity and ecosystems due to the disruption of interaction networks (Dunn and Hatcher 2015). In general, invasive plants reduce the diversity of native plant species and are predicted to also negatively impact native arthropod diversity (review in Spafford et al. 2013) through different mechanisms such as the alteration of vegetation structure or the loss of some plant species which host specialist arthropods. Few native specialist arthropods are present on the Kerguelen Islands, e.g., the moth Embryonopsis halticella which feeds on Poa cooki (Crafford and Scholtz 1986), and the fly Calycopteryx moseleyi (Tréhen et al. 1986), the weevils Bothrometopus angusticollis and Canonopsis sericea which feed on Pringlea antiscorbutica (Voisin et al. 2017), and the loss of their host-plant might particularly affect them.

Arthropods are highly dependent on plants (Schaffers et al. 2008; Joern and Laws 2013) and different components of plant community features affect them, such as plant composition, or morphological and physical attributes. For instance, plant height and lateral spread as well as leaf dimensions characterize plant architecture and determine the availability of different micro-habitat conditions allowing or not arthropods to choose optimal conditions of temperature, protection against wind, rain or predators (Spafford et al. 2013; Gardarin et al. 2018). By providing attachment points for spider webs, architectural traits may have an impact on predator hunting efficacy, depending on predator hunting strategy and on predator–prey interactions (Pearson 2009). Vegetation stature also influences the distribution of soil-dwelling arthropods likely through its correlation with litter quantity (Gardarin et al. 2018). For herbivores, which have direct interactions with plants since they feed on them, Carmona et al. (2011) showed that morphological and physical plant traits may act as a physical barrier and are often more important for plant–herbivore interactions than chemical traits. For instance, traits related to the biomechanical properties, such as cuticle thickness, specific leaf area (Ordonez et al. 2010), or leaf dry matter content (Deraison et al. 2015) have been shown to impact herbivore choice when selecting their food plant.

How arthropod communities reliant on native vegetation on sub-Antarctic islands, are impacted by non-native plants is yet to be tested (Houghton et al. 2019) and is difficult to predict. This is due to the absence or low richness of many insect groups (Gressit 1970; Vernon et al. 1998), and to the high interactions at play between native and non-native plants, native and non-native arthropods and between plants and arthropods (Houghton et al. 2019). Trait-based approaches have been proposed as useful tools to study plant-arthropod interactions at the community level (Lavorel et al. 2013; e.g., Deraison et al. 2015; Le Provost et al. 2017) and to understand community responses to biotic disturbance induced by non-native species (Gross et al. 2013; Mouillot et al 2013). This study aimed to investigate the effects of plant communities dominated by native or non-native plant species on macro- and micro-arthropod communities on three islands of the Kerguelen archipelago. On each of the studied islands, we selected relatively large areas of the two types of vegetation, i.e., native and non-native, that were close to each other. By considering plant traits involved in plant-arthropod interactions, i.e., plant architecture and leaf attributes, we assessed whether the plant functional community structure differed between the two types of vegetation using complementary indices, the functional dispersion and the community-weighted mean of traits (Mouillot et al. 2013). Secondly, we estimated the taxonomic diversity of macro-arthropods and their abundances as well as the abundances of epigaeic micro-arthropods in both types of vegetation. We then investigated whether these components of arthropod communities differed between native and non-native plant communities and whether plant functional diversity and community-weighted means of traits explained a significant part of their variability.

Material and methods

Study area and sampling design

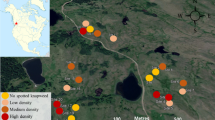

The study was conducted during the summer 2017–2018 on three islands of the Golfe du Morbihan in the Kerguelen archipelago (48° 30ʹ–50° S, 68° 27′–70° 35′ E): Île Australia, Île aux Cochons and Île Mayes (Fig. 1). Originally, plant communities were dominated by Acaena magellanica, Azorella selago, Festuca contracta and P. antiscorbutica. These plant assemblies covered Île Australia and Île Mayes until the 2010s. From these years, following climate change, non-native Poaceae and Asteraceae developed, in particular Poa pratensis and Taraxacum gr. ruderalia. These plants have expanded widely on Île Mayes, where meadows of P. pratensis covered large areas in 2016. On Île Australia, non-native Poaceae communities (P. pratensis, Vulpia bromoides) were still localized in 2016. Île aux Cochons differed from the other two islands by the presence of rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) until 1997, when they were eradicated (Chapuis et al. 2001). This mammal resulted in the rarefaction of P. antiscorbutica and A. selago, replaced by A. magellanica, which covered more than 90% of the island in 1997 (Chapuis et al. 2001, 2002). During the years 2000–2010, the increase in temperature and especially the low summer precipitations (Lebouvier et al. 2011) resulted in the significant regression of A. magellanica and the development of non-native Asteraceae (Taraxacum erythrospermum, T. gr. ruderalia) and Poaceae (in particular P. pratensis). Currently, the communities dominated by native species, i.e., A. magellanica, occupy small areas. All three islands have been colonized by mice, which have heavily predated and damaged their invertebrate fauna (Chapuis et al. 2002).

The sampling design consisted of areas of native- or non-native-dominated vegetation that were close to each other (a few tens of meters). It was implemented in herbaceous habitats which are the main habitats colonized by non-native plants. Sites corresponding to these criteria were preselected using a remote sensing based cartography of the vegetation on the three studied islands (Fourcy et al. 2018) (Fig. 2; see Online Resource 1 for a complete description of the classes). Vegetation maps were produced from a multispectral Pléiades image acquired in February 2016 (2 m ground spatial resolution) that we analyzed by performing a supervised classification with machine-learning algorithms. The supervised classification was based on botanical surveys conducted in December 2016 on training zones on Île Australia, Île aux cochons and Île Mayes, and used as references for the machine-learning algorithms.

Vegetation maps, based on Pléiades 1A PMS satellite image acquired in 2016, in 1 km2 areas around the sampled patches, and location of the sampled patches (centroids) within native and non-native areas. Native patches are in white and non-native patches in black and white. Vegetation was classified in 10 classes: Steppe dominated by non-native Poaceæ; Tall grassland of non-native Poaceæ; Mixed herbfield of native and non-native species; Tall herbfield of Acæna magellanica (ACAMA); Tundra of Azorella selago (AZOSE), A. magellanica and Festuca contracta (FESCO); Native herbfield of A. selago, A. magellanica and Pringlea antiscorbutica (PRIAN); Open cushion-carpet of A. selago; Mire; Steppe dominated by native Poaceæ; Fellfield. See Online Resource 1 for a detailed description of the classes. Maps highlight spatial patterns of vegetation, contrasting vegetation dominated by native plant species (in green) and vegetation dominated by non-native plants species (in yellow and pink)

Within each island, we selected in the field five sites among the preselected sites where an area covered with > 90% of native plant species was close to an area covered with > 90% of non-native plant species. The percent coverage of vegetation was estimated visually at that step. Then, we delineated a patch > 150 m2 within each of these areas and surveys were carried out within each patch. Distance between the two types of patch within a site ranged from 15 to 58 m. This resulted in 30 vegetation patches: 3 islands, 5 sites per island, 2 patches per site (one non-native, hereafter “non-native patch”, and one native, hereafter “native patch”) (Fig. 2). When selecting the sites, we controlled for abiotic conditions known to affect arthropods, such as the altitude, distance from the sea (Hullé and Vernon 2021), slope, dominant wind and sun exposures. All sites were at < 40 m altitude, > 50 m from the sea, with a slope < 20%. Sun and dominant wind exposures differed between sites and islands but not between paired patches (Online Resource 2).

Note that the sampling conditions varied during the study. Harsh weather conditions were observed in Île aux Cochons where a hailstorm occurred during one day and in Île Mayes where low temperatures (4.4 °C on average) and snowstorm occurred during three days. Conversely, sunny weather conditions were recorded throughout the sampling period in Île Australia.

Plant surveys and traits

A botanical survey was conducted within each of the 30 patches on the first day of the experiment (20th December 2017 on Île aux Cochons, 29th December 2017 on Île Australia, 9th January 2018 on Île Mayes). We used five quadrats of 0.50 m × 0.50 m haphazardly located within each patch. In each quadrat, we recorded the number of plant species and we estimated a percentage cover of the quadrat surface for each plant species. We calculated plant species diversity and mean cover of each plant species per patch over the five quadrats.

To characterize plant community features, seven plant traits reflecting important functions for plants (Diaz et al. 2016), and involved in plant-arthropod interactions (Carmona et al. 2011; Gardarin et al. 2018) were selected: plant height (PH) and plant width (PW), leaf length (LL) and leaf area (LA), leaf dry matter content (LDMC), specific leaf area (SLA), and leaf thickness (LT). In each island, 15–30 specimens of each plant species covering > 10% of at least one vegetation patch were measured and one leaf per plant was sampled, excepting A. selago and P. antiscorbutica for which we only sampled a total of 2–5 leaves. Traits were measured following standard protocols (Cornelissen et al. 2003) and their values were averaged over the number of plant or leaf specimens per plant species and island.

Arthropod sampling

On the first or second day of the experiment, we sampled arthropods in the 30 patches (one trapping session) using two types of trap to accurately estimate arthropod diversity: pitfall traps and yellow pans (Southwood 1978). We placed five pitfall traps (7.5 cm diameter, 5 cm depth) and two yellow pans (20 cm diameter) per patch. Pitfall traps were placed haphazardly in the patch, while yellow pans were placed on the ground and located so that the distance was the highest between the native patch and the non-native patch within each site. Traps were filled with a preservative solution of water, a few drops of liquid soap and salt (10 gL−1). All traps within an island were set up on the same day and left in place for four trapping days. We stored all caught arthropods in the lab in a 70% ethanol solution. Macro-arthropods were identified to the lowest possible taxonomic level (usually species) following Hullé et al. (2018). We identified winged aphids to species level while we pooled all wingless aphids together.

We characterized macro-arthropods, i.e., insects and spiders, by calculating their taxonomic richness and abundance. For this purpose, we defined different groups of macro-arthropods according to their origin status and trophic group according to Hullé and Vernon (2021). To calculate taxa richness, we first pooled for each patch all macro-arthropods collected either in pitfall traps or in yellow pans. Then, we calculated native, non-native and total taxa richness, which included taxa with unknown native or non-native status. We also calculated taxa richness of three trophic groups: decomposers (taxa feeding on plant material and omnivorous taxa), herbivores and predators. For macro-arthropod abundances, we considered native macro-arthropods and performed separate analyses for pitfall traps and for yellow pans, pooling all individuals sampled in each patch. We also analyzed the abundances of decomposers in yellow pans, herbivores in yellow pans and predators in pan traps by pooling all individuals sampled in each patch (see Badenhausser (2021) for a complete description of dataset). For micro-arthropods, we focussed on the abundances of Oribatida mites and Symphypleona springtails, which are generally epigaeic and tend to occur above or on the top of the ground surface (Greenslade 2002). We analyzed their abundances in pitfall traps by pooling all individuals sampled in each patch.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the R statistical software (R Development Core Team 2020) version 4.0.3 and packages car (Fox and Weisberg 2019), emmeans (Lenth 2020), factoextra (Kassambara and Mundt 2020), FactoMineR (Le et al. 2008), FD (Laliberté and Legendre 2010; Laliberté et al. 2014) and lme4 (Bates et al. 2015).

Characterization of plant functional community structure

Two complementary components of the functional structure of plant communities were assessed, i.e., functional composition and functional diversity (Laliberté and Legendre 2010; Mouillot et al. 2013). Plant functional composition was estimated using the community-weighted mean index calculated for each trait, CWM, and functional diversity using the multi-trait functional dispersion index, FDis. Both indices were calculated following Laliberté and Legendre (2010).

CWM is the mean trait value of the community, weighted by the relative cover of each plant species. It reflects the trait values of the dominant species in the community. It was computed separately for the seven measured traits (CWMTRAIT):

where n is the number of plant species in the vegetation patch, pj is the relative cover of species j in the patch (mean of species cover over the five quadrats per patch), and Tj is its mean trait value per island.

FDis is the mean distance in multidimensional trait space of individual species to the centroid of all species. It takes into account species abundances weighting distances of individual species by their relative abundances. Its minimum value is 0, when the community is composed of only one species. High FDis value in plant communities reflects a strong disparity in the distribution of traits. By providing a greater number of niches and microhabitats for arthropods, high FDis is expected to result in greater arthropod diversity (e.g., Deraison et al. 2015). It was computed as:

where n is the number of plant species in the vegetation patch, aj is the cover of species j in the patch (mean of species cover over the five quadrats per patch), zj is the distance of species j to the weighted centroid of the [xij] (trait × species) matrix, c:

We performed a principal component analysis (PCA) on the CWMTRAIT of the seven selected traits to describe plant community features in the two types of patch and to evaluate how they correlated.

We used Linear Mixed Effects Models (LMM) fitted by log-likelihood criterion to test for the effect of the island and type of patch on plant species richness, the seven CWMTRAIT and FDis. The interaction term between the type of patch and the island was included in the models since the effect of non-native plants may depend on the island and its invasion history. The site was included in the models as random effect to take into account for the effects of similar abiotic environmental conditions in the two patches per site. Models were simplified step by step by removing the interaction term and the main fixed effects if not significant (α = 0.05) using Wald Chi-square test, \({\chi }^{2}\). Parameters of the final models were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood (REML), and least-squares means were calculated. Predicted means were compared using Tukey method and adequate contrasts. Model errors were inspected for normality, constant mean and variance. Model formula was:

Effects of plant communities on arthropod communities

The effects of plant communities on the richness and abundance of arthropods were analyzed using LMM or Generalized Linear Mixed Effects Models (GLMM) depending on the distribution of the data and model errors, in order to satisfy the statistical assumptions of models. LMM was used for analyzing (i) the taxa richness of macro-arthropods: native species, non-native taxa (sqrt-transformed), all taxa (sqrt-transformed), decomposers (sqrt-transformed), herbivores and predators; (ii) the abundances of macro-arthropods: decomposers (log-transformed), herbivores (log-transformed), predators (log-transformed); (iii) the abundance of Oribatida mites (log-transformed). GLMM with Poisson errors was used for analyzing (i) the abundance of native macro-arthropods and (ii) the abundance of Symphypleona springtails.

First, we tested for the effects of the type of patch and plant FDis on the response variables mentioned above. We included in the models the island, the type of patch and their two-way interaction, and plant FDis as fixed effects. The site was included as random effect in all models. The model had the following structure: \(Y \sim \left(1|{\text{Site}}\right)+ {\text{Island}} \times {\text{Type of patch}} +{\text{FDis}}\)

Model simplification was conducted firstly by removing non-significant interaction term. Statistical assumptions were inspected, and model predictions and mean comparisons were performed as described above.

Second, we aimed to establish the relative importance of the functional composition of plant communities, namely CWMTRAITs and other components of plant community such as plant species identity, in shaping arthropod communities. However, collinearity issues occurred when including the type of patch and single CWMTRAITs in the same statistical models because CWMTRAITs and the type of patch were highly correlated (VIF values > 2) (Zuur et al. 2010). For this reason and as an exploratory analysis, we have limited the analysis of the effects of CWMTRAITs on arthropods to a comparison of models including either the type of patch or single CWMTRAITs. As described above, we run LMM or GLMM to model macro-arthropod taxa richness and abundances, and micro-arthropod abundances. Model formula for the patch model was:

Model formula for the CWMTRAIT models was:

After model simplification as described above, an information-theoretic approach (AIC-based approach corrected for small sample size; AICc; Burnham and Anderson 2002) was used to compare for each CWMTRAIT the simplified patch model and CWMTRAIT model. AICc difference (delta AICc) between the two models was calculated. If |delta AICc|< 2, models were not significantly different, while if |delta AICc|> 2 they differed, the best model being the one with the smallest AICc.

Results

Characterization of plant communities at the patch scale

Main native plant species in the patches were A. magellanica, A. selago, F. contracta, and P. antiscorbutica and main non-native species were P. pratensis generally associated with T. gr. ruderalia, and T. erythrospermum. Non-native plant species covered on average > 95% in non-native patches (Fig. 3d–f) while native plant species covered ~ 90% in native patches (Fig. 3a–c). Total plant species richness per patch did not vary between native and non-native patches (LMM: p (> \({\chi }_{1}^{2}\)) = 0.1484). It was significantly lower (LMM: p (> χ2) = 0.0230) on Île Australia (estimated mean ± SE, 3.1 ± 0.6 plant species) and Île Mayes (3.4 ± 0.6) than on Île aux Cochons (5.3 ± 0.8). These differences between islands were due to differences in non-native plant species richness in the native patches, which was higher on Île aux Cochons than on Île Mayes than on Île Australia (LMM: Island: p (> χ2) = 0.0001; Type of patch: p (> χ2) = 0.0030; Island × type of patch: p (> χ2) = 0.0321). Native plant species richness was the same in both types of patch and on the three islands (observed mean ± SE = 1.9 ± 0.3). The functional dispersion FDis did not vary between the types of patch but between islands (Table 1).

Mean plant species cover over the five quadrats per patch, in native and non-native patches in the islands studied: Île Australia a native patches d non-native patches, Île aux Cochons b native patches e non-native patches, Île Mayes c native patches f non-native patches). Native plant species: Acaena magellanica (ACAMA), Azorella selago (AZOSE), Deschampsia antarctica (DESAN), Festuca contracta (FESCO), Galium antarcticum (GALAN), Ranunculus biternatus (RANBI), Pringlea antiscorbutica (PRIAN); Non-native plant species: Cerastium fontanum (CERFO), Cerastium glomeratum (CERGL), Poa annua (POAAN), Poa pratensis (POAPR), Sagina procumbens (SAGPR), Stellaria alsine (STEAL), Stellaria media (STEME), Taraxacum erythrospermum (TARER), Taraxacum gr. ruderalia (TAROF), Vulpia bromoides (VULBR)

The PCA performed on CWMTRAITs showed that non-native and native patches formed distinct groups in the space of the two first PCA axes which accounted for 82.9% of the variance (Online Resource 3). The first PCA axis (60.1% of explained variance) mainly correlated to leaf dimensions, i.e., leaf length (CWMLL) (r = 0.96) and leaf area (CWMLA) (r = 0.86). The second PCA axis (22.8% of explained variance) correlated to leaf thickness (CWMLT) (r = 0.79).

All CWMTRAIT values differed significantly between native and non-native patches (Table 1). Native patches were characterized by low-stature plants, thick and small leaves, small SLA, and large LDMC. Non-native patches were characterized by large stature plants (+ 33% CWMPH; + 36% CWMPW), thiner leaves (− 45% CWMLT) with larger dimensions (+ 103% CWMLL; + 80% CWMLA), larger SLA (+ 38% CWMSLA) and smaller LDMC (− 15% CWMLDMC). All CWMTRAIT values but CWMSLA also differed between islands (Table 1).

Effects of plant communities on macro-arthropod communities

Overall, we collected nine native macro-arthropod species, 16 non-native taxa (among which 13 species), and four taxa not classifiable as native vs non-native species (Smittia sp., Ixodes spp., Siphonaptera, Thysanoptera). Among macro-arthropods, 785 of the collected individuals belonged to native species (560 in pitfall traps, 225 in yellow pans), 49 224 to non-native taxa and 108 specimens were not classifiable (70 Smittia sp., 36 Siphonaptera, one Ixodes spp., one Thysanoptera). One non-native taxa was numerically dominant, i.e., the aphids which represented > 90% of the total counts whatever the type of patch and island (see Badenhausser (2021) for a complete description of dataset).

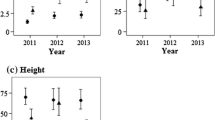

Macro-arthropod diversity and native macro-arthropod abundance

The same native macro-arthropod species with very few exceptions were collected in native and non-native patches within each island. They belonged to three trophic groups, i.e., decomposers, herbivores and predators. Taxa richness of native macro-arthropods was low and differed between islands (estimated means ± SE, Île Australia: 3.5 ± 0.4; Île aux Cochons: 2.7 ± 0.4; Île Mayes: 1.9 ± 0.4) (Table 2). The type of patch had no effect on the taxa richness of native macro-arthropods but plant FDis had a positive significant effect (Table 2) (LMM: Parameter estimate ± SE, 6.31 ± 3.11) suggesting that a wide variety of food niches or micro-habitats was favorable to native macro-arthropods. Taxa richness of non-native macro-arthropods was roughly twice the taxa richness of native macro-arthropods and differed between islands (Île Australia: 7.6 ± 0.7; Île aux Cochons: 5.1 ± 0.6; Île Mayes: 4.3 ± 0.5) (Table 2). The type of patch and FDis had no effect on the taxa richness of non-native macro-arthropods (Table 2). Total macro-arthropod richness per patch was the same in native and non-native patches on Île Australia (native patches: 11.9 ± 1.3; non-native patches: 13.7 ± 1.3) and Île aux Cochons (native patches: 9.2 ± 1.0; non-native patches: 7.6 ± 1.0) (Table 2). On Île Mayes, it was significantly lower in native patches (5.2 ± 0.8) relative to non-native patches (8.2 ± 1.0) (Table 2). FDis had a positive significant effect on total richness (Table 2).

The native spiders, Neomaso antarcticus and Myro kerguelensis, represented ~ 90% of the abundances of native macro-arthropods collected in pitfall traps whatever the type of patch and the island, and > 50% in yellow pans. Native macro-arthropod abundances in pitfall traps were significantly lower in native patches relative to non-native patches and differed between islands (Table 2; Fig. 4a). In addition, they increased significantly with FDis (Table 2) (GLMM: Parameter estimate ± SE, 2.46 ± 1.09). The island, type of patch, and FDis had no significant effect on the abundances of native macro-arthropods collected in yellow pans (GLMM: Island: p (> χ2) = 0.0966; Type of patch: p (> χ2) = 0.9381; Island × Type of patch: p (> χ2) = 0.2201; FDis: p (> χ2) = 0.1413).

Model predictions ± SE of the effect of the type of patch (native in green, non-native in red) on macro-arthropod abundance: a native species (pitfall traps) (see Table 2 for GLMM results), b herbivores (yellow pan counts), c decomposers (yellow pan counts) and d predators (pitfall trap counts) (see Table 2 for LMM results). Predictions are on a log scale. Shown are the results of the comparison between native and non-native patches (additive effect: p is the p-value of Chi-square test, χ2 in LMM or GLMM; interactive effect with the island: p is the p-value for comparing the estimates of native vs non-native patches within each island with Tukey’s method and paired contrasts)

Results of the comparison between the patch model and CWMTRAITs models showed that CWMPW and CWMLA models were better than the patch model in explaining the taxa richness of native macro-arthropods (Online Resource 4). In these models, CWMPW and CWMLA had opposite effects depending on the island (Online Resource 4). No CWMTRAIT model was selected as the best model relative to the patch model in explaining the non-native and total taxa richness, and the abundance of native species (Online Resource 4).

Diversity and abundance of trophic groups

Herbivores represented > 95% of the counts whatever the island and type of patch (Online Resource 5). This group was mainly composed of four aphid species among which Myzus ascalonicus was dominant (> 95% of winged aphids), and one thrips species Apterothrips apteris. Four native species represented other herbivores, which were very few (47 individuals in total). Singular fit occurred in LMM conducted on herbivore richness, which was not analyzed. Herbivore abundance was similar or higher depending on the island in non-native patches relative to native (Table 2; Fig. 4b). Plant FDis had strong effects on herbivore abundance, which increased with increasing FDis (Table 2) (LMM: Parameter estimate ± SE, 11.22 ± 3.58). In addition, CWMLL and CWMSLA models explained significantly more variability in herbivore abundance relative to the patch model (Online Resource 4). Herbivore abundance increased with increasing CWMLL and CWMSLA whose single effects were selected in the simplified models (Online Resource 4).

Decomposers (feeding on plant material and omnivorous pooled) represented ~ 1% of the macro-arthropods (Online Resource 5). This group was the richest with 13 taxa, among which the sciarid Lycoriella sativae represented half of the counts. Decomposer taxa richness was the same in both types of patch on Île Australia (estimated means ± SE, native patches: 4.4 ± 0.8, non-native patches: 5.1 ± 0.9), and Île aux cochons (native patches: 3.2 ± 0.7, non-native patches: 2.4 ± 0.6). It was higher in non-native patches relative to native patches on Île Mayes (native patches: 1.7 ± 0.5, non-native patches: 3.0 ± 0.7) (Table 2). The same results were observed for decomposer abundance (Table 2; Fig. 4c). FDis had no effect on decomposer taxa richness and abundance (Table 2). CWMLA and CWMLDMC models better modeled decomposer taxa richness than the patch model, and the effects of CWMLA and CWMLDMC differed between islands (Online Resource 4).

Predators represented 2.6% of the macro-arthropods collected in pitfall traps (Online Resource 5). Predator trophic group was composed of two native spider species, N. antarcticus, M. kerguelensis, and two non-native species, the spider Tenuiphantes tenuis, and the carabid beetle, Merizodus soledadinus (only 2.0% of the predators). Predator richness was the same in native and non-native patches on Île Australia (native patches: 3.0 ± 0.3; non-native patches: 3.4 ± 0.3) and on Île Mayes (native patches: 2.2 ± 0.3; non-native patches: 2.6 ± 0.3). On Île aux Cochons it was higher in native patches (3.2 ± 0.3) than in non-native patches (2.6 ± 0.3) (Table 2). Predators were significantly more abundant in non-native patches relative to native ones on Île Australia and Île Mayes (Table 2; Fig. 4d). On Île aux Cochons, they were as numerous in both types of patch (Table 2; Fig. 4d). Neither FDis nor CWMTRAITs had any effect on predator richness and abundance (Table 2, Online Resource 4).

Effects of plant communities on micro-arthropod communities

Overall, 9845 micro-arthropods were collected in pitfall traps among which 9001 Oribatida mites and 844 Symphypleona springtails. Oribatida mites represented > 80% of micro-arthropods on the three islands. Native patches had higher Oribatida mite (Fig. 5a) and Symphypleona springtail (Fig. 5b) abundances relative to non-native patches whatever the island (Table 2). FDis had a strong negative effect on Symphypleona springtails (GLMM: Parameter estimate ± SE, − 7.25 ± 1.00) while it had no effect on Oribatida mites (Table 2). Results of the comparison between the patch model and CWMTRAITs models showed that CWMPW model was better than the patch model in explaining Symphypleona abundance, which decreased with increasing CWMPW whatever the island (Online Resource 4).

Model predictions ± SE of the effect of the type of patch (native in green, non-native in red) on micro-arthropod abundance: a Oribatida mites (pitfall trap) (see Table 2 for LMM results), and b Symphypleona springtails (pitfall traps) (see Table 2 for GLMM results). Predictions are on a log scale. Shown are the results of the comparison between native and non-native patches (additive effect: p is the p-value of Chi-square test, χ2 in LMM or GLMM)

Discussion

Our study shows opposite effects of non-native plants on macro-arthropods and micro-arthropods. Despite strong differences in the functional composition of plant communities, we didn’t demonstrate any negative effect of non-native plants on native macro-arthropods. In fact, macro-arthropod diversity and abundance were similar or higher in non-native plant communities whatever their native or non-native status, and their trophic group. Conversely, micro-arthropods, i.e., Symphypleona springtails and Oribatida mites, abundances were higher in native plant communities relative to non-native. Finally, we found that plant functional diversity was similar in native and non-native plant communities, and benefited native macro-arthropods while it had a null or negative effect on micro-arthropods.

Functional structure of native and non-native plant communities

Trait-based indices, i.e., CWMTRAITs and FDis, were used to characterize the functional composition and diversity of native and non-native patches. Traits associated with leaf structure and quality were expected to be involved in trophic plant-arthropod interactions, and those with plant stature in non-trophic interactions through their effects on arthropod habitats (Lavorel et al. 2013; Gardarin et al. 2018). All CWMTRAITs differed between the two types of patch, reflecting the very high cover of respectively native and non-native plant species in the patches and trait differences between dominant native and non-native species. Dominant native plant species, i.e., A. magellanica and F. contracta, had low stature and leaf dimensions, low SLA and high LDMC, indicating low relative growth rate, low nutrient content and slow resource capture. They contrasted with dominant non-native species, i.e., P. pratensis and T. gr. ruderalia whose large stature and leaf dimensions, large SLA and low LDMC, correspond to fast-growth rate, high nutrient content and good light competitor (Diaz et al. 2016). Other studies also observed these characteristics in native and non-native plant communities (Ordonnez et al. 2010; Gross et al. 2013). We also found that FDis did not differ between native and non-native patches. This reflects the fact that native and non-native species did not mix or mixed very little within the patches. It also reflects similar range of trait disparity between the two dominant species within each type of patch, i.e., between a grass species (F. contracta in native patches and P. pratensis in non-native patches) and an herb species (A. magellanica in native patches and T. gr ruderalia in non-native patches).

Non-native plants have no negative effect on native macro-arthropods

Plant FDis significantly contributed to explaining the effect of plants on native macro-arthropods, which benefited as expected from a greater diversity of plant resources and micro-habitats in both native and non-native vegetation. Differences in the composition of native and non-native vegetation, did not lead to negative effects on native macro-arthropods. Although this result does not match the general expectation (review in Spafford et al. 2013), it is interesting to note that it is in agreement with the only published comparative study on the effect of non-native plants on invertebrates at the community scale, and in the context of sub-Antarctic islands (Gremmen et al. 1998). In this study, which focussed on soil fauna communities, native macro-invertebrate abundance was similar or higher in vegetation dominated by the non-native grass Agrostis stolonifera compared to vegetation dominated by A. magellanica. Obviously, non-native plants would have had a negative impact on specialist native macro-arthropods feeding on some particular native plant species. However, highly specialist native macro-arthropods were scarce in our study, probably because we focussed on herbaceous habitats, while specialist species were more likely to be found in fellfield habitats (Hullé and Vernon 2021). Two hypotheses may explain the lack of negative effects of non-native plants on native macro-arthropods. First, the spatial scale of our paired sampling design, i.e., the short distances separating native and non-native patches could result in native macro-arthropod communities being composed of the same species in both types of patch. Indeed, the mosaic landscape and entangled patterns of native and non-native plant communities observed on the islands studied (Fig. 2) may allow between-patch movements of individuals either actively walking, or flying, depending on species dispersal abilities, or passively carried by wind from and to nearby areas (Schooley and Wiens 2003). At the scale of the patch, higher abundances of some macro-arthropod species in non-native patches may be related to better local conditions provided by the non-native plants. Similar small-scale distribution patterns in arthropods depending on plant species within the vegetation mosaic have been described (e.g., Coulson et al. 2003). A second hypothesis is that interactions between non-native and native macro-arthropods play a greater role than plant-arthropod interactions in shaping native macro-arthropod communities. Indeed, an important feature of macro-arthropod communities was that non-native species outnumbered native in both types of vegetation, as already highlighted on Kerguelen archipelago (Frenot et al. 2005). For instance, the predatory beetle M. soledadinus had a strong impact on native invertebrates e.g., the flies Anatalanta aptera and C. moseleyi, resulting in their local extinction on some coastal habitats of the Kerguelen Islands (Lebouvier et al. 2020). In our surveys, M. soledadinus were few and could not have any impact on native arthropods. Dominant non-native taxa in our study were the aphids, which are sap-feeders and the thrips A. apteris, which feeds on the content of leaf cells (Karban and Strass 1994). By occupying previously vacant or unsaturated ecological niche (Russel et al. 2017; Houghton et al. 2019), they probably don’t compete with native species. Since data is missing from locations on the Kerguelen Islands that do not host non-native invertebrates (Hullé and Vernon 2021) against which to compare the diversity and abundance observed in our surveys, it is difficult to conclude on this hypothesis.

The abundance of macro-arthropods of different trophic groups is higher in non-native vegetation

Non-native plants also had no negative effect on macro-arthropods belonging to different trophic groups, i.e., herbivores, decomposers and predators whose diversity and abundance were similar or higher in non-native patches. The aphid M. ascalonicus and the thrips A. apteris much dominated among herbivores. Both species being polyphagous, they were able to feed on native and non-native species such as A. magellanica and T. gr ruderalia (Karban and Strauss 1994; Hullé et al. 2003). Plant FDis had an important contribution to explaining the abundance of macro-herbivores, which benefited as expected from diversified resources (Carmona et al. 2011; Moretti et al. 2013). This result highlights that the traits we selected were involved in herbivore-plant interactions, as also suggested by the strong positive effects of CWMSLA and CWMLL on herbivore abundance. Decomposers mainly comprised omnivorous taxa, which feed mostly on carcases or faeces of mammals and seabirds. Their weak trophic link with plants might explain their moderate response to native and non-native vegetation, as well as to plant FDis. Predator diversity and abundance were not impacted by plant FDis. Predators, i.e., three spiders, were more abundant in non-native patches relative to native, perhaps partly due to differences in prey availability, which is an important factor driving spider dynamics (Pearson 2009). Indeed, these species have a very large diet consisting mainly of small insects (larvae, adults) (Ysnel and Ledoux 1988), whose abundances were higher in non-native patches. This result may contribute to explain higher abundances of native macro-arthropods in non-native patches since the native spiders, N. antarcticus and M. kerguelensis, represented ~ 90% of their abundance.

The abundance of micro-arthropods is lower in non-native vegetation

Non-native plants had negative effects on the abundance of both Oribatida mites and Symphypleona springtails. This result was also observed at Marion Island where Symphypleona springtails and one dominant Oribatida species had higher abundances on the native plant species A. magellanica than on the non-native A. stolonifera (Gremmen et al. 1998). Several studies conducted in the sub-Antarctic islands, concluded that both mites and springtails were mainly controlled by abiotic factors, in particular plant or soil moisture and temperature (Travé 1981; McGeoch et al. 2006). Local plant community can have indirect effects on micro-arthropods through the effects of plant traits on local abiotic conditions, which in turn may affect micro-arthropods. For instance, such mechanisms were suggested to explain springtail responses to different plant functional groups (Eisenhauer et al. 2011). In this study, lower densities of springtails in the legume group were explained by higher plant biomass production, which, by depleting soil water content, directly affected springtails; it also depleted nutrients in the soil, which in turn negatively affected fungal growth, i.e., the amount of food available to springtails. Interestingly, FDis had a strong negative effect on Symphypleona springtails and no effect on Oribatida mites. These finding echoes that of Milcu et al. (2013) who found the same results, and suggested that the negative effect of FD on springtail abundance was mediated by its negative effect on root biomass. In contrast to macro-arthropods, micro-arthropods are less mobile and therefore they might not be able to reach the native patches such as macro-arthropods can do to find more resources. Further investigations on the relationship between plants, soil micro-arthropods and their main food resources, i.e., soil microbes, could allow understanding the mechanisms generating the results we observed. Indeed, we may hypothesize that the negative effects of non-native plants on Oribatida mites and Symphypleona springtails resulted at least partly from changes in the microbial networks in links to changes in plant communities (Boeddinghaus et al. 2019; Karimi et al. 2019).

Conclusion

Our study contributes to document the under-explored question of the interactions between plants and arthropods, in the context of biological invasions in the sub-Antarctic islands. This is particularly true for micro-arthropods, where the drivers of community assemblages, inter-specific interactions, species feeding preferences and ecology are largely unknown (Houghton et al. 2019). Our results point out the importance of conducting studies at different spatial scales and repeated over time, which could allow understanding the mechanisms by which non-native plants change native communities and modify the dynamics of both plant and arthropod communities. This would also make it possible to assess the long-term consequences for species conservation and ecosystem functioning. Indeed, by changing abundances of macro-arthropods belonging to different trophic groups and by depleting micro-arthropods, which are essential for nutrient cycling and primary production in terrestrial ecosystems, our findings suggest that non-native plant species may alter trophic interactions and whole ecosystem functioning in sub-Antarctic islands.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Data INRAE repository, https://doi.org/10.15454/DPILL6

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Badenhausser I (2021) Do non-native plants affect terrestrial arthropods in the sub-Antarctic Kerguelen Islands? https://data.inrae.fr/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:https://doi.org/10.15454/DPILL6

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67:1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Boeddinghaus RS, Marhan S, Berner D, Boch S, Fischer M, Hölzel N, Kattge J, Klaus VH, Kleinebecker T, Oelmann Y, Prati D, Schäfer D, Schöning I, Schrumpf M, Sorkau E, Kandeler E, Manning P (2019) Plant functional trait shift explain concurrent changes in the structure and function of grassland soil microbial communities. J Ecol 107:2197–2210. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.13182

Burnham KP, Anderson DR (2002) Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol Method Res 33:261–304

Carmona D, Lajeunesse M, Johnson M (2011) Plant traits that predict resistance to herbivores. Funct Ecol 25:358–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01794.x

Chapuis JL, Le Roux V, Asseline J, Lefèvre L, Kerleau F (2001) Eradication of rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) by poisoning on three islands of the subantarctic Kerguelen Archipelago. Wildl Res 28:323–331. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR00042

Chapuis JL, Frenot Y, Lebouvier M (2002) Une gamme d’îles de référence, un atout majeur pour l’évaluation de programmes de restauration dans l’archipel de Kerguelen. Rev Ecol (terre Vie) 9:121–130

Chown SL, Convey P (2016) Antarctic entomology. Annu Rev Entomol 61:119–137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010715-023537

Chown SL, Gremmem NJM, Gaston KJ (1998) Ecological biogeography of southern islands: species-area relationships, human impacts and conservation. Am Nat 152:562–575. https://doi.org/10.1086/286190

Collins GE, Hogg ID, Convey P, Sancho LG, Cowan DA, Lyons WB, Adams BJ, Wall DH, Green TGA (2020) Genetic diversity of soil invertebrates corroborates timing estimates for past collapses of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:22293–22302. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007925117

Cornelissen JHC, Lavorel S, Garnier E, Diaz S, Buchmann N, Gurvich DE, Reich PB, ter Steege H, Morgan HD, van der Heijden MGA, Pausas JG, Poorter H (2003) A handbook of protocols for standardised and easy measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Aust J Bot 51:335–380. https://doi.org/10.1071/BT02124

Coulson SJ, Hodkinson ID, Webb NR (2003) Microscale distribution pattern in high Artic soil microarthropod communities: the influence of plant species within the vegetation mosaic. Ecography 26:801–809. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0906-7590.2003.03646.x

Crafford JE, Scholtz CH (1986) Impact of Embryonopsis halticella Eaton larvae (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutidae) feeding in Marion Island tussock grassland. Polar Biol 6:191–196

Deharveng L, Travé J (1981) Ecologie des Oribates (Acariens) et des Collemboles (Insectes) de Kerguelen. CNFRA 48:109–140

Deraison H, Badenhausser I, Loeuille N, Scherber C, Gross N (2015) Functional trait diversity across trophic levels determines herbivore impact on plant community biomass. Ecol Lett 18:1346–1355. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele12529

Díaz S, Kattge J, Cornelissen JH, Wright IJ, Lavorel S, Dray S, Reu B, Kleyer M, Wirth C, Prentice IC, Garnier E, Bönisch G, Westoby M, Poorter H, Reich PB, Moles AT, Dickie J, Gillison AN, Zanne AE, Chave J, Wright SJ, Sheremet’ev SN, Jactel H, Baraloto C, Cerabolini B, Pierce S, Shipley B, Kirkup D, Casanoves F, Joswig JS, Günther A, Falczuk V, Rüger N, Mahecha MD, Gorné LD (2016) The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16489

Dunn AM, Hatcher MJ (2015) Parasites and biological invasions: parallels, interactions, and control. Trends Parasitol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2014.12.003

Eisenhauer N, Sabais ACW, Scheu S (2011) Collembola species composition and diversity effects on ecosystem functioning vary with plant functional group identity. Soil Biol Biochem 43:1697–1704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.04.015

Fourcy D, Chapuis JL, Lebouvier M, Robin M (2018) Combining satellite datasets to track changes in the vegetation of Kerguelen. In: POLAR2018 Abstract proceedings - Open Science Conference, 19–23 June 2018 Davos, Switzerland. Polar2018 SCAR/IASC Open Science Conference, Davos (CH). https://www.polar2018.org/uploads/2/4/6/0/24605948/polar2018_abstractproceedings.pdf

Fox J, Weisberg S (2019) An R companion to applied regression, 3rd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Frenot Y, Gloaguen JC, Massé L, Lebouvier M (2001) Human activities, ecoystem disturbance and plant invasions in subantarctic Crozet, Kerguelen and Amsterdam Islands. Biol Conserv 101:33–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00052-0

Frenot Y, Chown SL, Whinam J, Selkirk PM, Convey P, Skotnicki M, Bergstrom DM (2005) Biological invasions in the Antarctic: extent, impacts and implications. Biol Rev 80:45–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793104006542

Gardarin A, Plantegenest M, Bischoff A, Valantin-Morison M (2018) Understanding plant-arthropod interactions in multitrophic communities to improve conservation biological control: useful traits and metrics. J Pest Sci 91:943–955. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-0958-0

Greenslade P (2002) Assessing the risk of exotic Collembola invading subantarctic islands: prioritising quarantine management. Pedobiologia 46:338–344. https://doi.org/10.1078/0031-4056-00141

Greenslade P, Convey P (2012) Exotic Collembola on subantarctic islands: pathways, origins and biology. Biol Invasions 14:405–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-011-0086-8

Gremmen NJM, Chown SL, Marshall DJ (1998) Impact of the introduced grass Agrostis stolonifera on vegetation and soil fauna communities at Marion Island, sub-Antarctic. Biol Conserv 85:223–231

Gressit JL (1970) Subantarctic entomology and biogeography. Pac Insects Monogr 23:295–374

Gross N, Börger L, Duncan RP, Hulme PE (2013) Functional differences between alien and native species: do biotic interactions determine the functional structure of highly invaded grasslands? Funct Ecol 27:1262–1271. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12120

Houghton M, Terauds A, Merritt D, Driessen M, Shaw J (2019) The impacts of non-native species on the invertebrates of Southern ocean islands. J Insect Conserv 23:435–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-019-00147-9

Hullé M, Vernon P (2021) The terrestrial macro-invertebrates of the sub-Antarctic Îles Kerguelen and Île de la Possession. Iste-Wiley, London

Hullé M, Pannetier D, Simon JC, Vernon P, Frenot Y (2003) Aphids of sub-Antarctic Îles Crozet and Kerguelen: species diversity, host range and spatial distribution. Antarct Sci. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102003001184

Hullé M, Buchard C, Georges R, Vernon P (2018) Guide d’identification des invertébrés des Îles sub-Antarctiques Kerguelen et Crozet. 2 edn. Université Rennes 1. https://doi.org/10.15454/1.5375302767618145E12

Joern A, Laws AN (2013) Ecological mechanisms underlying arthropod species diversity in grasslands. Annu Rev Entomol 58:19–36. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153540

Karban R, Strauss SY (1994) Colonization of new host-plant individuals by locally adapted thrips. Ecography 17:82–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.1994.tb00079.x

Karimi B, Dequiedt S, Terrat S, Jolivet C, Arrouays D, Wincker P, Cruad C, Bispo A, Chemidlin Prévost-Bouré N, Ranjard L (2019) Biogeography of soil bacterial networks along a gradient of cropping intensity. Sci Rep 9:3812. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40422-y

Kassambara A, Mundt F (2020) factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses. R package version 1.0.7. http://www.sthda.com/english/rpkgs/factoextra

Laliberté E, Legendre P, Shipley B (2014) FD: measuring functional diversity from multiple traits, and other tools for functional ecology. R package version 1.0-12

Laliberté E, Legendre P (2010) A distance-based framework for measuring functional diversity from multiple traits. Ecology 91:299–305. https://doi.org/10.1890/08-2244.1

Lavorel S (2013) A novel framework for linking functional diversity of plants with other trophic levels for the quantification of ecosystem services. J Veg Sci 24:942–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.12083

Le Provost G, Gross N, Börger L, Deraison H, Roncoroni M, Badenhausser I (2017) Trait-matching and mass effect determine the functional response of herbivore community to land use intensification. Funct Ecol 31:1600–1611. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12849

Le S, Josse J, Husson F (2008) FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. J Stat Softw 25:1–18. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v025.i01

Lebouvier M, Laparie M, Hullé M, Marais A, Cozic Y, Lalouette L, Vernon P, Candresse T, Frenot Y, Renault D (2011) The significance of the sub-Antarctic Kerguelen Islands for the assessment of the vulnerability of native communities to climate change, alien insect invasion and plant viruses. Biol Invasions 13:1195–1208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-011-9946-5

Lebouvier M, Lambret P, Garnier A, Convey P, Frenot Y, Vernon P, Renault D (2020) Spotlight on the invasion of a carabid beetle on an oceanic island over a 105-year period. Sci Rep 10:17103. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72754-5

Lenth RV (2020) emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.5.3. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans

McGeoch MA, Le Roux PC, Hugo EA, Chown SL (2006) Species and community responses to short-term climate manipulation: microarthropods in the sub-Antarctic. Austral Ecol 31:719–731. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2006.01614.x

McGeoch MA, Shaw JD, Terauds A, Lee JE, Chown SL (2015) Monitoring biological invasion across the broader Antarctic: a baseline and indicator framework. Glob Environ Change 32:108–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.12.012

Milcu A, Allan E, Roscher C, Jenkins T, Meyer ST, Flynn D, Bessler H, Buscot F, Engels C, Gubsch M, Konig S, Lipowsky A, Loranger J, Renker C, Scherber C, Schmid B, Thebault E, Wubet T, Weisser WW, Scheu S, Eisenhauer N (2013) Functionally and phylogenetically diverse plant communities key to soil biota. Ecology 94:1878–1885. https://doi.org/10.1890/12-1936.1

Moretti M, de Bello F, Ibanez S, Fontana S, Pezzatti G, Dziock F, Rixen C, Lavorel S (2013) Linking traits between plants and invertebrate herbivores to track functional effects of land-use changes. J Veg Sci 24:949–962. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.12022

Mouillot D, Graham NAJ, Villéger S, Mason NWH, Bellwood DR (2013) A functional approach reveals community responses to disturbance. Trends Ecol Evol 28:167–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2012.10.004

Ordonez A, Wright IJ, Olff H (2010) Functional differences between native and alien species: a global-scale comparison. Funct Ecol 24:1353–1361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01739.x

Pearson DE (2009) Invasive plant architecture alters trophic interactions by changing predator abundance and behaviour. Oecologia 159:549–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-008-1241-5

Pertierra LR, Aragon P, Shaw JD (2017) Global thermal niche models of two European grasses shows high invasion risks in Antarctica. Glob Change Biol 23:2863–2873. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13596

R Development Core Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Russel JC, Meyer JY, Holmes ND, Pagad S (2017) Invasive alien species on islands: impacts, distribution, interactions and management. Environ Conserv 44:359–370. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892917000297

Schaffers AP, Raemakers IP, Sykora KV, Ter Braak CJF (2008) Arthropod assemblages are best predicted by plant species composition. Ecology 89:782–794. https://doi.org/10.1890/07-0361.1

Schooley RL, Wiens JA (2003) Finding habitat patches and directional connectivity. Oikos 102:559–570. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12490.x

Shaw JD, Spear D, Greve M, Chown SL (2010) Taxonomic homogenization and differentiation across Southern Ocean Islands differ among insects and vascular plants. J Biogeogr 37:217–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02204.x

Southwood TRE (1978) Ecological methods, with particular reference to the study of insect populations. Chapman and Hall, London

Spafford RD, Lortie CJ, Butterfield BJ (2013) A systematic review of arthropod community diversity in association with invasive plants. Neobiota 16:81–102. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.16.4190

Travé J (1981) Structure des peuplements de microarthropodes à Kerguelen. Essai de synthèse. Colloque Sur Les Écosystèmes Terrestres Subantarctiques, CNFRA 51:73–80

Tréhen P, Vernon P, Delettre Y, Frenot Y (1986) Organisation et dynamique des peuplements diptérologiques à Kerguelen. Mise en évidence de modifications liées à l’insularité. CNFRA 58:241–253

Vernon P, Vannier G, Tréhen P (1998) A comparative approach to the entomological diversity of polar regions. Acta Oecol 19:303–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1146-609X(98)80034-9

Voisin JF, Chapelin-Viscardi JD, Ponel P, Rapp M (2017) Les Coléoptères de la province de Kerguelen (îles subantarctiques de l'océan Indien). Faune de France 99, Fédération Française des Sociétés de Sciences Naturelles, Paris

Ysnel F, Ledoux JC (1988) Données sur le cycle biologique de quelques araignées des terres australes françaises (Kerguelen, Crozet). Bulletin De La Société Scientifique De Bretagne 59:209–221

Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Elphick CS (2010) A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Methods Ecol Evol 1:3–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00001.x

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Peter Convey and two anonymous referees for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. The authors thank M. Lebouvier and G. Le Provost for useful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. The authors thank all the contributors involved in the long-term plant and arthropod monitoring carried out within the framework of the programme 136 (IPEV). This research was supported by the ‘Institut Polaire Français Paul-Emile Victor’ (IPEV, programme 136), and the CNRS (Zone-Atelier de Recherches sur l’Environnement Antarctique et Subantarctique).

Funding

The research was supported by the ‘Institut Polaire Français Paul-Emile Victor’ (IPEV, programme 136 subanteco) and the CNRS (Zone-Atelier de Recherches sur l’Environnement Antarctique et Subantarctique).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IB and MH conceived and designed research. IB, MB, AP conducted experiments. IB and BB identified arthropods. DF developed analytical tools to analyze Pléiades images and produced vegetation maps. YR designed geostatistical application for fieldwork. JLC provided long-term plant database. IB analyzed data. IB and MH wrote the manuscript. DF and JLC commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Research involving human and animal rights

Authors obtained all the appropriate permissions for collecting arthropods in the “Réserve naturelle des Terres australes françaises”. Arrêté no 2017-113 12nd October 2017, Terres Australes et Antarctiques Françaises.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Badenhausser, I., Fourcy, D., Bertrand, M. et al. Do non-native plants affect terrestrial arthropods in the sub-Antarctic Kerguelen Islands?. Polar Biol 45, 491–506 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-022-03010-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-022-03010-x