Abstract

Previous studies investigating the risk of erectile dysfunction (ED) among patients with gout have produced inconsistent evidence. Therefore, the aim of this meta-analysis was to investigate the relationship between gout and the risk of ED. The Embase, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science and Cochrane Library databases were searched for all studies assessing the risk of ED in patients with gout. Relative risks (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were adopted to estimate the association between gout and the risk of ED. Sensitivity analyses were applied to evaluate the robustness of results. Overall, 355,761 participants were included from 8 studies (3 cross-sectional and 5 cohort studies). Of these, 85,067 were patients with gout. Synthesis results showed patients with gout had a 1.2-fold higher risk of ED than individual without gout (RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.10–1.31, P < 0.001). The results of sensitivity analysis are consistent with the trend of synthesis results. The present meta-analysis revealed that the risk of ED in patients with gout was dramatically increased when compared with the general population, which suggests that clinicians should assess erectile function when treating an individual who suffers from gout.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gout has been known as one of the most relapsing inflammatory arthritis, which is typically characterized by the deposition of monosodium urate crystals involving joints and adjacent tissues [1, 2]. It was reported that the global incidence of gout was 0.08% [3]. It was widely accepted that gout is a kind of peripheral arthritis disease which may affect patients far beyond the joint. Higher risk of developing comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease [4], hyperlipidemia [5], obesity [6], chronic kidney disease [7], as well as diabetes mellitus [8] was found in patients with gout than general population. All these co-morbidities may influence the sexual function of patients with gout. In addition, patients with gout compared with the general population experienced a significantly higher risk for developing psychiatric comorbidities, such as depression, which could affect sexual health of subjects with gout [9]. Thus, a close link between gout and sexual dysfunction may exist.

The most common sexual problems among men are erectile dysfunction (ED). It was reported that the prevalence of ED ranged from 1 to 10% among men younger than 40 years, and 50% among 40- to 70-year-old men [10]. ED is a multifactorial condition. Several factors, such as biological and psychological, have been reported to be associated with ED [11]. Over the past several years, several studies have described the relationship between gout and ED, which have reported that the proportion of ED was found to be significantly higher in patients with gout compared with patients without gout [12, 13].

Although a high risk of ED in patients with gout has been detected, however, controversial results still persisted. Hence, the link between gout and ED warrants further exploration. We drew this meta-analysis to comprehensively evaluate the connection between gout and ED and provide a more reliable evidence.

Methods

This meta-analysis was conducted base on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [14]. The PRISMA checklist was presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Literature search

Literature was searched from the Embase, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science and Cochrane Library databases. The time frame spanned from the inception of these databases to April 2019. The search was focused on English language and human participants. The following keywords were applied in searching: (gout) AND (((erectile dysfunction) OR impotence) OR sexual dysfunction). In addition, the reference lists of retrieved articles were reviewed to identify other pertinent studies.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) original observational studies (cohort, case–control, or cross-sectional) that assessed the association between gout and risk of ED among male humans; (2) the included studies should have provided relative risk (RR) estimates or odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or primary data to calculate them. The exclusion criteria were: (1) the control data were not provided; (2) studies were review or meta-analysis; (3) meeting abstracts, comments, editorials, letters, case reports, or congress reports; (4) animal experiments.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The following information was extracted from all eligible publications by two authors independently: the first author’s last name, year of publication, country of study, study design, case and control sample sizes, mean age of participants, diagnosis criteria for ED, statistical adjustments for confounding factors, and effect measures (RR or OR) with 95% CI.

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was applied to examine the quality of the cohort studies [15]. The cross-sectional study quality methodology checklist was used for the cross-sectional study [16]. Studies with seven to nine points were arbitrarily considered high quality.

Statistical analyses

The degree of agreement between the two authors was measured using the Kappa statistic. The adjusted pooled RRs and 95% CIs were applied to evaluate the association between gout and the risk of ED. It was considered statistically significant when P values less than 0.05. The I2 statistic and the Cochrane Q statistic were calculated to assess the heterogeneity of included studies (I2 > 50% was considered of substantial heterogeneity; a P value of Q test < 0.10 was considered statistically significant). The random-effects model was accepted when there was significant statistical heterogeneity (I2 > 50%, P < 0.10). Otherwise, a fixed-effects model was adopted [17]. Sensitivity analysis and subgroup analyses were applied to explore the origin of heterogeneity. The Begg and Egger tests were performed to examine publication bias [18, 19]. The present statistical analysis was performed using STATA 13.0 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Literature search

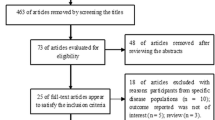

The study selection process was presented in Fig. 1. At the end, eight articles were included in this meta-analysis [12, 13, 20,21,22,23,24,25]. The two authors had a high degree of agreement (Kappa statistic = 0.70).

Study characteristics

The descriptive data of the included studies were summarized in Table 1. All eligible studies were published between 2010 and 2019. Of the included studies, three were cross-sectional studies [13, 21, 22] and five were cohort studies [12, 20, 23,24,25]. A total of 355,761 participants were included. The sample size in the studies ranged from 70 to 154,332 adults. These studies were carried out in the Taiwan (n = 2) [12, 20], United States (n = 2) [13, 25], England (n = 3) [22,23,24], and Korea (n = 1) [21].

Study quality

The outcome of the quality assessment for the five cohort studies was presented in Supplementary Table 2, of which two studies [12, 23] were judged as moderate quality and the remaining three study [20, 24, 25] was judged as high quality. The outcome of the methodologic quality assessment of the cross-sectional studies was presented in Supplementary Table 3, one study [22] was moderate quality and two studies were high quality [13, 21].

Synthesis of results

As shown in Fig. 2, individuals with gout compared with the individuals without gout experienced a significantly high risk of ED (RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.10–1.31, P = 0.000; heterogeneity: I2 = 75.8%, P = 0.000) using a random-effects model, which indicated that gout is strongly associated with an increased risk of ED.

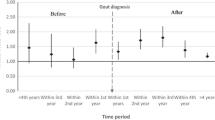

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were applied to evaluate the reliability of our analysis. Each study was eliminated in turn to recalculate the pooled RR. The results presented the similar trend. The RRs ranged from 1.16 (95% CI 1.11–1.21) to 1.23 (95% CI 1.13–1.34) after excluding any study (Table 2; Supplementary Figure 1).

Subgroup analyses

To further evaluate the association between gout and risk of ED, subgroup analyses were performed based on age, publication year, study design, geographic region, method of assessment for ED (Table 3). Stratified analysis by age shown that a similar association was detected in men younger than 50 years (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.10–1.34, P < 0.001) and those older than 50 years (RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.06–1.35, P < 0.001). In the subgroup analysis based on publication year, the RRs were 1.19 (95% CI 1.02–1.38, P = 0.029) and 1.23 (95% CI 1.08–1.39, P = 0.002) for studies published before 2015 and after 2015, respectively. Moreover, subgroup analysis by study design shown a statistically significant correlation between gout and risk of ED in the cohort studies (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.12–1.32, P = 0.000); however, no association between gout and risk of ED was observed in the cross-sectional (RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.56–3.22, P = 0.51). When further stratified by geographic region, a statistically significant association between gout and risk of ED was observed for Taiwan (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.10–1.34, P = 0.000), England (RR 1.18, 95% CI 1.04–1.34, P = 0.01); however, a similar association was not found in United States (RR 1.72, 95% CI 0.70–4.26, P = 0.24) and Korea (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.11–3.53, P > 0.05). In the subgroup analysis based on methods of assessment for ED, the RRs were 1.26 (95% CI 1.07–1.48, P = 0.006) and 1.19 (95% CI 1.07–1.32, P = 0.001) for studies used IIEF-5 assessment for ED and used ICD codes assessment for ED, respectively.

Publication bias

Publication bias was absent based on Begg and Egger test (Begg test, P > |z| = 0.902; Egger test, P > |t| = 0.521; Fig. 3).

Discussion

Over the past few decades, the role of gout in the development of ED have drawn researchers’ attention, but inconsistent results were found. A cohort study by Sultan et al. in England, who recruited 9653 patients with gout and 38,218 general population, they reported that patients with gout had a 1.31-fold higher odds in ED subjects than the general population [24]. However, Maynard et al. found that gout was not significantly associated with the risk of ED (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.85–1.53, P > 0.05) [25]. The present meta-analysis sum up all the observational studies on the effect of gout on the risk of ED. The current meta-analysis indicated a 20% increase in the risk of ED among subjects with gout compared with those without gout. When the sensitivity analyses were conducted, the quantification of the risk for ED remained same trend as before. This finding was consistent with recent clinical trials [12, 13, 24], which revealed that the risk of ED was found to be obviously higher in patients with gout compared with the general population. In addition, our results were consistent with previous studies that analyzed the association between other arthritis and risk of ED (e.g., ankylosing spondylitis [26], rheumatoid arthritis [27]).

Different comorbidities can affect the risk of ED. In the present meta-analysis, eight articles provided the RR of multivariable adjustment for confounding factors, such as age, smoking, coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, depression and anxiety. Thus, we had good reasons to believe that the results in the current meta-analysis seemed reliable and robust.

Although many evidences have shown that gout might be linked with ED, no clear-cut etiology has been identified to interpret this close connection. Several factors may contribute to the development of ED in gout. The close link between gout and hyperuricemia may be a possible contributor [28]. Gout is a chronic inflammatory arthritis characterized by urate crystal deposition. Hyperuricaemia is a prerequisite [29]. Mounting evidence has emerged indicating that hyperuricaemia could increase the risk of ED. Base on a case–control study by Salem et al., who recruited 251 patients with ED and 252 age-matched subjects without ED. They found that the level of serum uric acid was found to be distinctly higher in patients with ED (6.12 ± 1.55 mg/dl) compared with subjects without ED (4.97 ± 1.09 mg/dl) (P < 0.001). For each 1 mg/dl increase in serum uric acid level, the risk of ED increase twofold [30]. Long et al. found that the ratio of ICPmax (maximum intracavernosal pressure)/MAP (mean arterial pressure) was found to be distinctly decreased in hyperuricemic rats compared with controls [31]. The hazardous effect of hyperuricemia on the erectile function may be primarily mediated by endothelial dysfunction. In penile tissues, nerve and endothelium-derived nitric oxide (NO) is the strongest factors for penile smooth muscle relaxation and erection [32]. It has been reported that the rat with hyperuricemic compared with the control group experienced a markedly decreased expression of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) as well as nitric oxide (NO) [33]. An explanation for this link was that patients with gout had increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity [34,35,36]. It is well-known that endothelial dysfunction was the common pathogenesis of ED and cardiovascular disease [37]. Cardiovascular disease was recognized as the risk factors for the development of ED [38].

In addition, inflammation may play an important role for the development of ED in patients with gout. Gout is an inflammatory arthritis [1]. It was reported that patients with ED compared with subjects without ED had significantly higher plasma levels of inflammatory factors, such as hsCRP, IL-6, IL-1β, these factors negative related with sexual health [39,40,41].

Another underlying mechanism for gout and the risk of ED may be vitamin D deficiency. Vanholder et al. reported that the synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3 could be inhibited by uric acid among patients with renal failure and hyperuricemia [42]. Serum 1,25(OH)2D3 level was lower in individuals with gout when compared with general population [43]. Barassi et al. reported that vitamin D was inadequate in a large proportion of patients with ED. Individual who had a vitamin D deficiency may experience an increased risk of ED due to the endothelial dysfunction [44].

On the other hand, previous studies shown that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was high in patients with gout, ranging from 30.1 to 82.0% [45]. Choi et al. reported that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was 62.8% (51.9–73.6) among individuals with gout and 25.4% (23.5–27.3) among individuals without gout [46]. Intriguingly, metabolic syndrome was recognized as the hazardous factors for the development of ED [47, 48]. In addition, psychiatric such as depression also potentially involved the development of ED in gout. Base on a meta-analysis, it was reported that patients with gout had a distinctly increased risk of depression [9]. It was known that patients with depression had an increased risk of developing ED [49]. Since the pathogenesis of ED in patients with gout attributed to multi-factors, the treatment for those patients should be based on their chief complaint and specific symptoms.

Despite the advantages of this study, however, it was not without limitations. First, all included studies were observational studies, which can introduce selection bias or recall bias. Second, we did not perform the subgroup analysis based on the duration of gout and treatment for gout, because there was an absence of this information in most included studies. Third, although publication bias was absent, but bias might exist for the published data due to only English publications were searched. Fourth, the difference of risk of ED between acute and chronic gout was not performed due to the including studies did not provide the relative data. Therefore, further well-designed studies are needed to confirm the relationship of gout predisposing to the development of ED.

Conclusions

In summary, our results demonstrated that patients with gout have a significantly elevated risk of ED, which suggests that the erectile function should be assessed when clinicians manage patients with gout and provide corresponding specific therapies for patients with gout when necessary.

References

Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Mallen C, Zhang W, Doherty M (2015) Rising burden of gout in the UK but continuing suboptimal management: a nationwide population study. Ann Rheum Dis 74(4):661–667. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204463

Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK (2011) Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008. Arthritis Rheum 63:3136–3141. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30520

Smith E, Hoy D, Cross M et al (2014) The global burden of gout: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 73:1470–1476. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204647

Lee KA, Ryu SR, Park SJ, Kim HR, Lee SH (2018) Assessment of cardiovascular risk profile based on measurement of tophus volume in patients with gout. Clin Rheumatol 37(5):1351–1358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-017-3963-4

Thottam GE, Krasnokutsky S, Pillinger MH (2017) Gout and metabolic syndrome: a tangled web. Curr Rheumatol Rep 19(10):60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-017-0688-y

Lee J, Lee JY, Lee JH et al (2015) Visceral fat obesity is highly associated with primary gout in a metabolically obese but normal weighted population: a case control study. Arthritis Res Ther 24(17):79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0593-6

Roughley MJ, Belcher J, Mallen CD, Roddy E (2015) Gout and risk of chronic kidney disease and nephrolithiasis: meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Res Ther 17:90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0610-9

Tung YC, Lee SS, Tsai WC et al (2016) Association between gout and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Med 129(11):1219.e17–1219.e25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.06.041

Lin S, Zhang H, Ma A (2018) Association of gout and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 33(3):441–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4789

Pushkar’ DIu, Kamalov AA, Al’-Shukri SKh et al (2012) Analysis of the results of epidemiological study on prevalence of erectile dysfunction in the Russian Federation. Urologiia 6:5–9

Hatzichristou D, Kirana PS, Banner L et al (2016) Diagnosing sexual dysfunction in men and women: sexual history taking and the role of symptom scales and questionnaires. J Sex Med 13:1166–1182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.05.017

Chen YF, Lin HH, Lu CC et al (2015) Gout and a subsequent increased risk of erectile dysfunction in men aged 64 and under: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. J Rheumatol 42(10):1898–1905. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.141105

Schlesinger N, Radvanski DC, Cheng JQ, Kostis JB (2015) Erectile dysfunction is common among patients with gout. J Rheumatol 42(10):1893–1897. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.141031

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Stang A (2010) Critical evaluation of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 25:603–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z

Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J (2003) The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 3:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-3-25

Higgins JP, Thompson SG (2002) Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 21:1539–1558. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1186

Begg CB, Mazumdar M (1994) Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50(4):1088–1101

Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315:629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

Hsu C-Y, Lin C-L, Kao C-H (2015) Gout is associated with organic and psychogenic erectile dysfunction. Eur J Intern Med 26(9):691–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2015.06.001

Kim JH, Chung MK, Kang JY et al (2019) Insulin resistance is an independent predictor of erectile dysfunction in patients with gout. Korean J Intern Med 34(1):202–209. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2016.350

Roddy E, Muller S, Hayward R, Mallen C (2012) Gout, allopurinol and erectile dysfunction: an epidemiological study in a primary care consultation database. Rheumatology (United Kingdom) 51:iii38

Schlesinger N, Lu N, Choi HK (2018) Gout and the risk of incident erectile dysfunction: a body mass index-matched population-based study. J Rheumatol 45(8):1192–1197. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.170444

Abdul Sultan A, Mallen C, Hayward R et al (2017) Gout and subsequent erectile dysfunction: a population-based cohort study from England. Arthritis Res Ther 19(1):123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1322-0

Maynard JW, McAdams MA, Baer AN et al (2010) Erectile dysfunction is associated with gout in the campaign against cancer and heart disease (CLUE II). Arthritis Rheum 62:1544

Fan D, Liu L, Ding N et al (2015) Male sexual dysfunction and ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rheumatol 42(2):252–257. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.140416

Keller JJ, Lin HC (2012) A population-based study on the association between rheumatoid arthritis and erectile dysfunction. Ann Rheum Dis 71(6):1102–1103. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200890

Pluta RM, Shmerling RH, Burke AE, Livingston EH (2012) JAMA patient page. Gout JAMA 308(20):2161. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.4095

Robinson PC (2018) Gout—an update of aetiology, genetics, co-morbidities and management. Maturitas 118:67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.10.012

Salem S, Mehrsai A, Heydari R, Pourmand G (2014) Serum uric acid as a risk predictor for erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med 11:1118–1124. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12495

Long H, Jiang J, Xia J et al (2016) Hyperuricemia is an independent risk factor for erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med 13(7):1056–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.04.073

Lue TF (2000) Erectile dysfunction. N Engl J Med 342:1802–1813. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm200006153422407

Kim YW, Park SY, Kim JY et al (2007) Metformin restores the penile expression of nitric oxide synthase in high-fat-fed obese rats. J Androl 28:555–560. https://doi.org/10.2164/jandrol.106.001602

Abeles AM, Pillinger MH (2019) Gout and cardiovascular disease: crystallized confusion. Curr Opin Rheumatol 31(2):118–124. https://doi.org/10.1097/bor.0000000000000585

Choi HK, Curhan G (2007) Independent impact of gut on mortality and risk for coronary heart disease. Circulation 116(8):894–900

Pan A, Teng GG, Yuan JM, Koh WP (2015) Bidirectional association between self-reported hypertension and gout: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. PLoS One 10(10):e0141749. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141749

Vlachopoulos C, Ioakeimidis N, Terentes-Printzios D, Stefanadis C (2008) The triad: erectile dysfunction–endothelial dysfunction–cardiovascular disease. Curr Pharm Des 14(35):3700–3714

Kostis JB, Jackson G, Rosen R et al (2005) Sexual dysfunction and cardiac risk (the second princeton consensus conference). Am J Cardiol 96(12B):85M–93M. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.12.018

Blans MC, Visseren FL, Banga JD et al (2006) Infection induced inflammation is associated with erectile dysfunction in men with diabetes. Eur J Clin Investig 36:497–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01653.x

Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Ioakeimidis N et al (2006) Unfavourable endothelial and inflammatory state in erectile dysfunction patients with or without coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 27:2640–2648. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehl341

Giugliano F, Esposito K, Di Palo C et al (2004) Erectile dysfunction associates with endothelial dysfunction and raised proinflammatory cytokine levels in obese men. J Endocrinol Investig 27:665–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03347500

Vanholder R, Patel S, Hsu CH (1993) Effect of uric acid on plasma levels of 1,25(OH)2D in renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 4:1035–1038

Takahashi S, Yamamoto T, Moriwaki Y, Tsutsumi Z, Yamakita J, Higashino K (1998) Decreased serum concentrations of 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 in patients with gout. Adv Exp Med Biol 431:57–60

Barassi A, Pezzilli R, Colpi GM, Corsi Romanelli MM, Melzi d’Eril GV (2014) Vitamin D and erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med 11:2792–2800. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12661

Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK (2012) Comorbidities of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: NHANES 2007–2008. Am J Med 125:679–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.09.033

Dao HH, Harun-Or-Rashid M, Sakamoto J (2010) Body composition and metabolic syndrome in patients with primary gout in Vietnam. Rheumatology (Oxford) 49:2400–2407. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keq274

Besiroglu H, Otunctemur A, Ozbek E (2015) The relationship between metabolic syndrome, its components, and erectile dysfunction: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Sex Med 12:1309–1318. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12885

Maseroli E, Corona G, Rastrelli G et al (2015) Prevalence of endocrine and metabolic disorders in subjects with erectile dysfunction: a comparative study. J Sex Med 12:956–965. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12832

Liu Q, Zhang Y, Wang J et al (2018) Erectile dysfunction and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med 15(8):1073–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.05.016

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the grants from Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (No. 2017B030314108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception or design of the work: ZGZ and LML. Data collection: QX and YHD. Data analysis and interpretation: SKZ, ZGZ and YZL. Drafting the article: LML. Critical revision of the article: ZGZ, JMW. Final approval of the version to be published: ZGZ and LML. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, L., Xiang, Q., Deng, Y. et al. Gout is associated with elevated risk of erectile dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int 39, 1527–1535 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04365-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04365-x