Abstract

Background

The xiphoid process (XP) in animals such as sheep and rats are well known to have cartilage called xiphoidal cartilage (XC). In humans, the cartilage in the xiphoid process is considered an anatomical variant and is not well understood. The aim of this study was to investigate the morphology of the XP.

Methods

A total of twenty embalmed European descendant cadaveric sterna (aged 52 to 98 years) were used. Transilluminated XPs and midsagittal sections of XPs were used to examine the bone and cartilage. Subsequently, a sagittally-sectioned XP was harvested for histology and stained with Masson’s trichrome. The results of the transillumination and histological examinations were compared qualitatively.

Results

The dark area visible in transilluminated XPs was consistent with the bony part in the midsagittal XP sections, which contained bone marrow; the bright area was consistent with the cartilage part in the midsagittal XP sections. This was all demonstrated histologically. Most of the XPs (85%) had some portion of cartilage. The XP was classified into four types based on its proportions of bone and cartilage: Type I, no ossification (< 1/3 ossification) 45%; Type II, minor ossification (1/3 − 1/2 ossification) 20%; Type III, major ossification (1/2–2/3 ossification) 20%; Type IV, complete ossification (> 2/3 ossification) 15%. Most of the XPs (85%) had bone and cartilage, which could have been overlooked in studies using skeletons or CT.

Conclusion

Previous studies probably underestimated or overestimated the size of the XP. The XC needs to be considered as normal anatomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

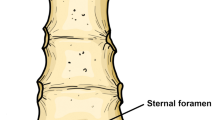

The xiphoid process (XP) is the smallest and most variable sternal element in the epigastrium. It can be thin, broad, bent, bifid or trifid, pointed or perforated (foramen). It can be misdiagnosed as an epigastric mass if it is elongated and curved forwards. It is cartilaginous at birth, begins to ossify in the third year or later, and is more or less ossified in adults [18]. It is continuous with the lower end of the sternal body at the xiphisternal joint. There are demifacets articulating with parts of the seventh costal cartilage anterior to its superolateral angles [18]. Gross anatomical and radiological studies of the XP have been conducted. Xie et al. [20] classified XPs into different types on the basis of their morphology using multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) and cadavers. Akin et al. [1], using MDCT, reported that the XP was absent in 1.1% of cases and showed no ossification in 2.3%. There have been several studies on the sternal foramina [3, 5, 14]. The previous literature, using dry bones or CT images, has mainly discussed the presence or absence of foramina, bifid or trifid XPs, or variant ossification of the XP. A recent case report by Sue et al. [19] described an XP with a large foramen, curvature, and partial ossification as a unique variation. However, as most XP studies have used skeletons or CT evidence, the prevalence of ossification and the detailed morphology are still unknown.

It is well known that some animals such as rats [13, 21] and sheep [12] have xiphoid (xiphoidal) cartilage (XC) as normal anatomy. In some animals, the XC is even synonymous with the XP [7]. In human anatomy, as aforementioned, the XC can be considered an anatomical variant [6]. Descriptions of the human XC, as found in old literature, are scant [2]. The aim of this study was to investigate the morphology of the human XP to reveal how the XC is associated with it.

Materials and methods

A total of twenty embalmed European descendant cadaveric sterna (thirteen females and seven males) whose ages at death ranged from 52 to 98 years (mean: 80.0) were used.

After all the soft tissue was removed, except the cartilaginous tissue attached to the XP, transillumination was used to reveal the bone and cartilage parts (transilluminated XP) []. The XP was then cut through the middle to assess the relative proportions of bone and cartilage (midsagittal section of XP). Subsequently, a sagittally-sectioned xiphoid process was harvested for histology and embedded in paraffin. A microtome was used to cut 5 μm slices, which were stained with Masson’s trichrome, and the specimen was examined under a light microscope. Finally, the results of the transillumination and histological examinations were compared qualitatively. The prevalences of bifid XPs and xiphoidal foramina were also noted during observation.

No previous surgical scars or obvious pathology were observed in the skin of the thorax, sternum, or surrounding area. This study was performed in accordance with the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki (64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013).

All observations were obtained by two anatomists (J.I. and R.S.)

The authors state that every effort was made to follow all local and international ethical guidelines and laws that pertain to the use of human cadaveric donors in anatomical research [10].

Results

The dark area in transilluminated XPs was consistent with the bony part in the midsagittal XP section, which contained bone marrow (hard tissue, hard to cut). The bright area was consistent with the cartilaginous part in the midsagittal XP section (soft tissue, easy to cut) (Fig. 1). This was all demonstrated histologically after Masson trichrome staining. Most XPs had some portion of cartilage. The XP was classified into four types on the basis of the relative proportions of bone and cartilage (Fig. 2):

Comparison between the transilluminated XP (A) and a midsagittal XP section (B) The dark area shown in transilluminated XP was consistent with the bony part in the midsagittal XP section, which contained bone marrow (arrows). The bright area was consistent with the cartilage part in the midsagittal XP section (arrowheads)

Type I, no ossification (< 1/3 ossification) 45% (9/20).

Type II, minor ossification (1/3 − 1/2 ossification) 20% (4/20).

Type III, major ossification (1/2–2/3 ossification) 20% (4/20).

Type IV, complete ossification (> 2/3 ossification) 15% (3/20).

Bone and cartilage constituted the entire XP in most specimens, but the prevalences of bifid XPs/XP foramina with or without cartilage differed. Among the bifid XPs, 20% (4/20) had cartilage and 40% (8/20) did not. Among the xiphoid foramina, 20% (4/20) had cartilage and 10% (2/20) did not (see type III in Fig. 2).

One unique anatomical variation was noted in a 77-year-old female specimen. The XP was not clearly visualized in the anterior view of the thorax. However, two very long legs were identified in the posterior view (Fig. 3). Histological examination revealed that the XP could have been visualized as one with a foramen when the cartilaginous part was removed.

Variant xiphoid process in a 77-year-old female specimen. A: The xiphoid process was not clearly visualized in the anterior view of the thorax, but two very long legs and a foramen-like structure were identified in the posterior view. B: The midsagittal section of the variant xiphoid process stained with Masson trichrome shows cartilaginous tissue (arrowheads) between bones superior and inferior to it (arrows)

Discussion

XP cartilage (XC) was identified in most specimens, 85%, in the present study. Over a long period of history, anatomists have taught that the XP is a part of the sternum and consists of bone, only rare exceptions including cartilage. A possible reason is that the anatomy of the sternum has been taught using skeletons or CT, neither of which shows cartilage. Another reason could be the name of the XP. The term “xiphoid” is derived from the Greek word xiphos, which means “straight sword,” implying a hard, sharp, and straight structure. This could make us think that the XP is something straight comprising only hard tissue. Interestingly, some clinical literature has occasionally mentioned the XC [2]. Hanlon et al. [8] reported a patient who complained of heaviness in the pit of the stomach caused by a deformed XP. Their article described the XP as consisting of cartilage with a core of bone that enlarges with age. The treatment was described as excision of the cartilage.

What are true xiphoid foramina or bifid XP?

Sternal foramina on the xiphoid process have been reported in 2.5-57.77% using cadavers and DCT [21]. Forked-shaped XPs (equivalent to bifid XPs) have been found in 11.65–21.95%; some could also be trifid [4, 17]. The true prevalence of the xiphoid foramen was 20% (4/20) in the present study. However, if dried skeletons had been used, the prevalence would have been 10% (2/20) because part of the foramen is cartilage. True bifid XPs were 20% (4/20) in the present study but would have been 40% (8/20) had dried skeletons been used. Therefore, previous reports on the prevalence of both xiphoid foramina and forked-shaped XPs (bifid XP) could have been over- or under-estimated. The XP must have been smaller than actual size (length, width) in those previous studies using dried skeletons.

Development and ossification of the XP

Occasionally, researchers have identified the XC without histology [19]. As shown in Fig. 3, only histological examination can reveal the structures in the space between the bones [11]. In the present study, there was more ossification in proximal (superior) parts of the XPs and less in distal (inferior) ones, but Fig. 3 shows one exception. Here, the proximal and distal parts were ossified but not the middle.

There are six ossification centers in the development of the sternum: one in the manubrium, four in the body, and one in the XP. Ossified areas can be identified only in the manubrium and mesosternum at birth. The XP begins to ossify in the third year or later. Ossification of the sternebrae should be completed at around 25 years old [16, 22]. All cadaveric specimens in the present study were over 50 years old, so ossification should have been complete, but cartilage was still present in most of them. Only 15% (3/20) of the XPs showed complete ossification, so cartilage within the XP should be considered as normal anatomy.

Future direction

Since cartilage is composed solely of chondrocytes, which have very poor turnover capacities, regeneration of it remains a major challenge [15]. A comprehensive anatomical understanding of the XP is therefore essential. The results of the present study provide a fundamental basis for revisiting, modifying, or even developing a medical treatment.

Conclusions

The vast majority of XPs (85%) had bone and cartilage, which could have been overlooked in studies using skeletons or CT. Previous studies could have underestimated or overestimated the size of the XP. The term “xiphoid process” should comprise bony and cartilaginous parts. The cartilage needs to be considered as normal anatomy.

Limitations

The age of cadavers might affect the ossification of the cartilage. Some cartilaginous tissue might have been removed during dissection.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Code availability

Not applicable

References

Akin K, Kosehan D, Topcu A, Koktener A (2011) Anatomic evaluation of the xiphoid process with 64-row multidetector computed tomography. Skeletal Radiol 40(4):447–452

Bramwell W (1902) A minute peritoneal hernia through a cleft in the xiphoid cartilage. Lancet 159(4104):1177

Choi PJ, Iwanaga J, Tubbs RS (2017) A Comprehensive Review of the Sternal Foramina and its clinical significance. Cureus 9(12):e1929

Chun T, Iwanaga J, Dumont AS, Tubbs RS (2022) Trifid and ventrally curved xiphoid process with two sternal foramina. Surg Radiol Anat 44(9):1253–1255

El-Busaid H, Kaisha W, Hassanali J, Hassan S, Ogeng’o J, Mandela P (2012) Sternal foramina and variant xiphoid morphology in a Kenyan population. Folia Morphol 71(1):19–22

FIPAT (2019) Terminologia Anatomica, 2nd edn. Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology

Guan M, Pan D, Zhang M, Leng X, Yao B (2021) Deer antler extract potentially facilitates xiphoid cartilage growth and regeneration and prevents inflammatory susceptibility by regulating multiple functional genes. J Orthop Surg Res 16(1):208

Hanlon CR, Miller MM (1954) Deformity of the xiphoid cartilage associated with gastrointestinal symptoms. J Am Med Assoc 154(12):992–993

Iwanaga, J., Singh, V., Ohtsuka, A., Hwang, Y., Kim, H. J., Moryś, J., Ravi, K. S.,Ribatti, D., Trainor, P. A., Sañudo, J. R., Apaydin, N., Şengül, G., Albertine, K.H., Walocha, J. A., Loukas, M., Duparc, F., Paulsen, F., Del Sol, M., Adds, P., Hegazy,A., … Tubbs, R. S. (2021). Acknowledging the use of human cadaveric tissues in research papers: Recommendations from anatomical journal editors. Clinical anatomy (New York,N.Y.), 34(1), 2–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.23671

Iwanaga, J., Singh, V., Takeda, S., Ogeng’o, J., Kim, H. J., Moryś, J., Ravi, K. S.,Ribatti, D., Trainor, P. A., Sañudo, J. R., Apaydin, N., Sharma, A., Smith, H. F.,Walocha, J. A., Hegazy, A. M. S., Duparc, F., Paulsen, F., Del Sol, M., Adds, P.,Louryan, S., … Tubbs, R. S. (2022). Standardized statement for the ethical use of human cadaveric tissues in anatomy research papers: Recommendations from Anatomical Journal Editors-in-Chief. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.), 35(4), 526–528. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.23849

Iwanaga J, Kikuchi K, Tabuchi K, Dave M, Anbalagan M, Fukino K, Kitagawa N, Reina MA, Reina F, Carrera A, Nonaka T, Rajaram-Gilkes M, Khalil MK, Matsushita Y, Tubbs RS (2024) A histology guide for performing human cadaveric studies: SQIP 2024 what to look for with light microscopy. 37(5):555–562 Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.24156

Kaferstein FK (1970) A trial to assess the value of xiphoid cartilage measurements and carcass weight for age determination in sheep. N Z Vet J 18(8):149–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00480169.1970.33885

Nam S, Cho W, Cho H, Lee J, Lee E, Son Y (2014) Xiphoid process-derived chondrocytes: a novel cell source for elastic cartilage regeneration. Stem Cells Translational Med 3(11):1381–1391. https://doi.org/10.5966/sctm.2014-0070

Paraskevas G, Tzika M, Anastasopoulos N, Kitsoulis P, Sofidis G, Natsis K (2015) Sternal foramina: incidence in Greek population, anatomy and clinical considerations. Surg Radiologic Anatomy: SRA 37(7):845–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-014-1412-5

Oldershaw RA (2012) Cell sources for the regeneration of articular cartilage: the past, the horizon and the future. Int J Exp Pathol 93(6):389–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2613.2012.00837.x

O’Neal ML, Dwornik JJ, Ganey TM, Ogden JA (1998) Postnatal development of the human sternum. J Pediatr Orthop 18(3):398–405

Pasquinelly A, Delaviz H, Maklad A, Frank PW (2022) Proposed neural crest involvement in concomitant bifid xiphoid process and atrial septal defect: a case study and review of literature. Transl Res Anat 29:100225

Standring S (2021) Gray’s anatomy. The anatomical basis of clinical practice, 42nd edn. Elsevier, London

Sue M, Lombardi P, Li ASR, Bola H, Bentley DC (2024) Discovery of an Anteriorly deviated, partially ossified xiphoid process with a large, teardrop-shaped Foramen in a male cadaver. Cureus 16(5):e61068. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.61068

Xie YZ, Wang BJ, Yun JS, Chung GH, Ma ZB, Li XJ, Kim IS, Chai OH, Han EH, Kim HT, Song CH (2014) Morphology of the human xiphoid process: dissection and radiography of cadavers and MDCT of patients. Surg Radiologic Anatomy: SRA 36(3):209–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-013-1163-8

Yao B, Zhou Z, Zhang M, Leng X, Zhao D (2022) Comparison of Gene expression patterns in articular cartilage and xiphoid cartilage. Biochem Genet 60(2):676–706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10528-021-10127-x

Yekeler E, Tunaci M, Tunaci A, Dursun M, Acunas G (2006) Frequency of sternal variations and anomalies evaluated by MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 186(4):956–960. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.04.1779

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank those who donated their bodies to science so that anatomical research could be performed. Results from such research can potentially increase mankind’s overall knowledge that can then improve patient care. Therefore, these donors and their families deserve our highest gratitude [9].

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JI; Writing-original draft, formal analysis, RS; Writing – original draft. KBS; Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing. JJC; Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing KK; Writing - Review & Editing, AC; Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing. AS; Resources, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing. RST; Resources, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The protocol of the study did not require approval by the ethical committees or informed consent. The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki (64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013).

Financial disclosure statement

None.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Iwanaga, J., Samrid, R., Shelvin, K.B. et al. Revisiting morphology of xiphoid process of the sternum in human: a comprehensive anatomical study. Surg Radiol Anat 46, 1687–1692 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-024-03463-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-024-03463-1