Abstract

Background

In view of importance for competency-based education (CBE), we undertook a self-study to elicit the available operative surgical workload and supervision for residents in the general surgical residency program at the teaching hospital in Karachi.

Methodology

This was a cross-sectional study spanning a 5-year period between January 2015 and December 2019. The numbers of surgical residents during this period were identified. Five procedures were selected as core general surgical procedures: incision and drainage of superficial abscess, laparoscopic appendectomy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, open inguinal hernia repair, and perianal procedures. Trends of the number of residents per year and the numbers of procedures per year were determined. The mean number of core procedures per eligible resident during their entire training was calculated to represent potential operative surgical experience and were benchmarked. The ratio of the average number of residents rotating in general surgery per year to the number of attending surgeons was determined as a measure of available supervision.

Result

The mean total number of general surgical residents per year was 31.2 (range 28–35). The numbers of core general surgical procedures were consistent over the years of study. Potential exposure of eligible residents to each core procedure during their entire training was: 19.5 cases for incision and drainage of superficial abscess; 89 cases for laparoscopic appendectomy; 113.6 for inguinal hernia repair, 267.5 for laparoscopic cholecystectomy and 64.5 for perianal procedures. The average yearly residents to full-time attending surgeons’ ratio was 2.5. The workload of core general surgical procedures at AKUH was higher than the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) recommended volumes for operative surgical experience for residents in the US.

Conclusion

This method of assessing the potential of a surgical program for transitioning to CBE appears practical and can be generalized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adequate training in a surgical specialty has become a challenge as available operative surgical experience has declined significantly for trainees in the US and the UK, leading to discussions on instituting appropriate changes in training methods [1,2,3,4]. The decline in experience is multifactorial but mainly due to reductions in resident’s duty hours out of concern for patient’s safety and to enhance the quality of the lifestyle of the trainees [5, 6]. Consequent to limited experience with operative surgery during training, there have been concerns about the graduate’s technical competence and self-confidence [7]. Lack of confidence is the main reason for why 80% of general surgery trainees graduating from US training programs opt for post residency fellowship training [7, 8].

Hospital volumes for surgical procedures are known to have a salutary effect on training experience and graduating surgeon’s competence as well as confidence. In a national survey of final year residents in 249 general surgery programs in the US, the factors influencing confidence in performing surgical procedures were evaluated among final year residents. The type of specialty, geographic location of the program, and surgical volumes, both in the final year of residency and all through training, were independently associated with confidence levels [9]. Confidence stems from competence not only in technical procedural skills but also in pre, intra-and post-operative decision-making, communication, teamwork, professional behavior, cost-effective utilization of resources, and overall patient care.

Competency-based education (CBE) has emerged as the potential solution; it requires an acceptable level of competence to be achieved by all trainees before they graduate [10]. Thus, as surgical trainees advance, they are entrusted to manage patients with increasingly complex surgical conditions and perform essential surgical procedures under remote supervision [11].

Operative surgical experience deserves special attention in competency-based surgical training with two features standing out as initial indicators of the quality of training: (a) adequacy of available operative surgical workload and (b) adequacy of the ratio of trainees to supervising attending surgeons [12, 13]. To the best of our knowledge, these indicators are not being used currently for accreditation of training programs in Pakistan. In the present study, we used these indicators to audit the general surgery residency program at the Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH) in preparation for transitioning to CBE. The General Surgery Residency Program at AKUH is a 5 year residency program (exclusive of internship) and is accredited by the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Pakistan (CPSP).

Method

This study was conducted in the section of General Surgery at AKUH, which is a JCIA accredited private, tertiary care, teaching hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. In discussions with attending surgeons, and educational and research staff, we identified five core general surgical procedures that residents should master by the end of their training; they were:

-

1.

Incision and drainage of superficial abscesses,

-

2.

Laparoscopic appendectomy,

-

3.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy,

-

4.

Open inguinal hernia repair and

-

5.

Perianal procedures.

The number of surgical trainees during the years 2015 to 2019 were identified using office records. As per curricular requirements of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Pakistan (CPSP), residents inducted in various subspecialities (Neurosurgery, Orthopedics, Cardiothoracic Surgery, Plastic Surgery, Urology, and Pediatric Surgery) are required to rotate in General Surgery for a defined number of months during their first 2 years of training. These residents have been included in the total number of residents. All year one and year two resident including residents from subspecialities spent the same time in general surgery and assigned rotations for initial 2 years. Their objectives and requirements of minimum number of surgical procedures performed were also same. The opportunities were also similar between residents of general surgery and those rotating from other specialties. The trends of the number of residents per year, per level of training (available in office records) led to determination of the average (mean) number of residents per year at a given level of training.

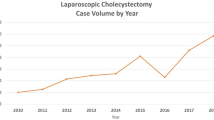

The numbers of core general surgical procedures performed in the operating rooms per year during the 5-year period between 2015 and 2019 were determined using the Hospital Information Management System (HIMS). The mean number for each core procedure per year was further determined.

The number of eligible residents for a given core procedure was determined based on the resident’s handbook which assigns procedures for development of competency based on the resident’s level of training. The mean number of eligible residents for a given core procedure; the mean number of core procedures per year; the mean number of core procedures per eligible resident per year; and the mean number of core procedures per eligible resident during the entire duration of training for that procedure (representing the potential volume of operative surgical experience) were calculated. Operative surgical workload available at AKUH were benchmarked against international standards.

The average number of residents divided by the number of attending surgeons provided the resident to attending surgeons ratio and represents the potential supervision available. Since general surgery residents are also required to rotate in other specialties as per CPSP requirements, the numbers of residents reflects only those residents rotating in general surgery; those rotating in other specialties were excluded.

Results

Between 2015 and 2019, the total number of general surgery residents per year ranged between 28 and 35, with a mean of 31.2 residents per year (Table 1). The numbers of core general surgical procedures were consistent over these years (Table 2). Potential exposure of eligible residents to core procedures during the entire training program was calculated as: 19.5 cases for incision and drainage of superficial abscess; 89 cases for laparoscopic appendectomy; 113.6 for inguinal hernia repair, 267.5 for laparoscopic cholecystectomy and 64.5 for perianal procedures (Table 3).

The number of fulltime attending surgeons remained unchanged during the study period (n = 7); however, the number of residents rotating in general surgery varied from year to year; with an average of 18. Thus, the average residents to attending surgeons’ ratio in general surgery were 2.5 (Table 4).

The volume of core general surgical procedures available at AKUH was higher than the volume recommended for operative surgical experience of residents by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education in USA (Table 5).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to make an initial assessment using indicators of the volume of operative surgical experience and of supervisory capacity to assess whether the general surgery program at AKUH was well placed to transition to CBE; in other words, to determine whether the number of enrolled residents was commensurate with the available workload of core general procedures and the number of attending surgeons available to provide supervision. Table 5 shows that the numbers of core procedures available per resident at AKUH based on eligibility were much higher than the numbers recommended by ACGME to be performed independently (though under supervision) by general surgery residents in the US to be eligible for certification [14]. It is fair to say that the AKUH general surgery program exceeds international benchmarks in terms of the volume of operative surgical experience for these procedures.

A caveat that should not be ignored is that these numbers represent procedures performed in the operating rooms. Incision and drainage of abscesses and some peri-anal procedures are routinely performed by residents under supervision in the outpatient setting and in the emergency room. These procedures are not captured by the HIMS system mentioned previously. The exposure of residents to these particular procedures is higher than reflected in the numbers detailed above.

Mastery of operative surgical skills is an important determinant of surgical outcomes. A critical factor for converting potential to actual experience is the availability of adequate and appropriate supervision of residents by attending surgeons/faculty. The resident-to-faculty ratio is a rough indicator of available supervision. At AKUH, this ratio is 2.5 in general surgery if only fulltime faculty are considered. In addition, non-full time faculty also supervise residents. While the main responsibility for training residents lies with the faculty, senior residents and fellows routinely supervise junior colleagues. AKUH resident-to-faculty ratio in general surgery seems quite adequate when compared to American College of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) recommended ratio of one faculty to six residents [15]. This supervision can be further enhanced toward the concept of ‘coaching’ which involves one on one interaction whereby the faculty coach enables each individual trainee to master his/ her operative surgical skills [16].

The work environment has a substantial role to play in ensuring adequate and appropriate supervision. A lot depends on the quality of interaction between residents and attending surgeons; motivation is required on the part of both to balance patient safety with growth in the trainees’ competence and confidence [17]. The quality of supervision is also influenced by other factors as pressures on operating room time. In a private teaching hospital, the cost of additional time for training tends to be passed on to patients. Anxious not to let this happen, the attending surgeon may want to expedite the surgical procedure resulting in excessive supervision, frequent interruptions, and early takeover of the procedure from the trainee [18]. Besides, efficiency i.e., completing the procedure in the allocated time, and concern for patient outcomes are also known to limit appropriate supervision [19]. Patients and their families expectations are yet other factors to consider; nearly 80% of patients in a survey, wished to minimize resident’s involvement in their surgical procedure [20]. More work needs to be done to determine the level of satisfaction with supervision at AKUH. In public teaching hospitals, lack of resources and anxiety on the part of attending surgeons to conclude their operating room lists efficiently in order to get to their private practice may impair the quality of supervision.

It is important to find ways to motivate attending surgeons to fulfill their roles as coaches, team leaders and role models; information that operating time for common surgical procedures whether done by the attending surgeon or resident need be no different, could provide comfort [21]. Simulation-based learning can also better prepare trainees for surgery on real patients [22]. Simulation provides a conducive and controlled learning environment with freedom from concern for patient safety; it can also be used to refine non-technical skills such as communication, time management, professionalism, and team management [23].

Although the method proposed is practical, for generalizability to other institutions local factors would need to be considered e.g., determining what procedures are core, based on case mix and availability of expertise and technology such as for laparoscopic surgery. Available operative workload and resident to attending surgeon ratios are not quite the same as actual supervised operative surgical experience leading to attainment of competence; several factors would need to be considered to make the conversion from potential to actual e.g., attributes of trainees and attending surgeons; program design and governance; quality of the work environment; and institutional policies.

In order to evaluate actual experience including supervision and trainee’s learning from the experience, it will be necessary to maintain resident’s logbooks meticulously. Unfortunately, logbooks are not rigorously maintained at present, they simply serve to secure eligibility to appear in an exit examination. Residents, faculty supervisors and examiners will need to be educated about the benefits of maintaining a reflective logbook to improve performance; logistical issues such as time required to complete a logbook entry by hand will need to be overcome; and appropriate, validated tools will need to be introduced to assess resident’s operative performances for providing feedback [24].

Conclusion

This is the first study of its kind in Pakistan for initial self-assessment of a surgical program to judge its suitability for transitioning to CBE based on commensurability between the number of residents in training and available operative surgical workload and supervision by attending surgeons. At AKUH, compared with international benchmarks, the available workload for core general surgical procedures is adequate for the number of residents enrolled; however, the ratio of residents to full-time attending surgeons may be less than ideal for coaching to achieve mastery of operative surgical skills.

The method is generalizable to other institutions, provided adjustments for local factors are made, such as the types of procedures regarded as core. To convert the available operative workload and resident to attending ratios into actual supervised operative surgical experience leading to attainment of competence, several factors would need to be considered e.g., the attributes of trainees and attending surgeons; program design and governance; quality of the work environment; and institutional policies. This study can serve as initial reference for self-assessment for available operative experience and faculty supervision at the institutions, aiming to implement CBE curricula for surgical training.

References

Morris PJ (2004) RCS response on training time for surgeons. BMJ 328:1133

Toll EC, Davis CR (2010) More trainees and less operative exposure: a quantitative analysis of training opportunities for junior surgical trainees. Bull Roy College Surg England 92(5):170–173

Varley I, Keir J, Fagg P (2006) Changes in caseload and the potential impact on surgical training: a retrospective review of one hospital’s experience. BMC Med Educ 6(1):6

Kairys JC, McGuire K, Crawford AG, Yeo CJ (2008) Cumulative operative experience is decreasing during general surgery residency: a worrisome trend for surgical trainees? J Am Coll Surg 206(5):804–811

Donaldson L, Britain G (2002) Unfinished business: proposals for reform of the senior house officer grade: a paper for consultation. Department of Health, London

Morris-Stiff GJ, Sarasin S, Edwards P, Lewis WG, Lewis MH (2005) The European working timedirective: one for all and all for one? Surgery 137(3):293–297

Borman KR, Vick LR, Biester TW, Mitchell ME (2008) Changing demographics of residents choosing fellowships: long term data from the American Board of Surgery. J Am Coll Surg 206(5):782–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.012

George BC, Bohnen JD, Williams RG, Meyerson SL, Schuller MC, Clark MJ, Meier AH, Torbeck L, Mandell SP, Mullen JT, Smink DS (2017) Readiness of US general surgery residents for independent practice. Ann Surg 266(4):582–594

Fonseca AL, Reddy V, Longo WE, Gusberg RJ (2014) Graduating general surgery resident operative confidence: perspective from a national survey. J Surg Res 190(2):419–428

Stride HP, George BC, Williams RG, Bohnen JD, Eaton MJ, Schuller MC, Zhao L, Yang A, Meyerson SL, Scully R, Dunnington GL (2018) Relationship of procedural numbers with meaningful procedural autonomy in general surgery residents. Surgery 163(3):488–494

Elsey EJ, Griffiths G, West J, Humes DJ (2019) Changing autonomy in operative experience through UK general surgery training: a national cohort study. Ann Surg 269(3):399

Ericsson KA (2007) An expert-performance perspective of research on medical expertise: the study of clinical performance. Med Educ 41(12):1124–1130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02946.x

Singh P, Aggarwal R, Pucher PH, Duisberg AL, Arora S, Darzi A (2014) Defining quality in surgical training: perceptions of the profession. Am J Surg 207(4):628–636

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Defined Category Minimum Numbers for General Surgery Residents and Credit Role. Available from: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/DefinedCategoryMinimumNumbersforGeneralSurgeryResidentsandCreditRole.pdf [Accessed 21st May 2021].

ACGME International Foundational Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education available at https://www.acgme-i.org/Portals/0/FoundInternationalresidency.pdf?ver=2020-02-14-141811-923 (Accessed on 20th Jan 2022)

Greenberg C, Ghousseini HL, Pavuluri Quamme SR, Beasley HL, Wiegmann DA (2015) Surgical coaching for individual performance improvement. Ann Surg 262:32–34

Cooper A, Allen S (2019) Resident autonomy. In: Contemporary Topics in Graduate Medical Education 2019 May 15. IntechOpen.

Ko CY, Escarce JJ, Baker L, Sharp J, Guarino C (2005) Predictors of surgery resident satisfaction with teaching by attendings: a national survey. Ann Surg 241(2):373

Teman NR, Gauger PG, Mullan PB, Tarpley JL, Minter RM (2014) Entrustment of general surgery residents in the operating room: factors contributing to provision of resident autonomy. J Am Coll Surg 219(4):778–787

Dickinson KJ, Bass BL, Nguyen DT, Graviss EA, Pei KY (2021) Public perception of general surgery resident autonomy and supervision. J Am Coll Surg 232(1):8–15

Uecker J, Luftman K, Ali S, Brown C (2013) Comparable operative times with and without surgery resident participation. J Surg Educ 70(6):696–699

Mittal MK, Dumon KR, Edelson PK, Acero NM, Hashimoto D, Danzer E, Selvan B, Resnick AS, Morris JB, Williams NN (2012) Successful implementation of the American College of Surgeons/Association of Program Directors in Surgery: surgical skills curriculum via a 4-week consecutive simulation rotation. Simulation Healthcare 7(3):147–154

Windsor JA (2009) Role of simulation in surgical education and training. ANZ J Surg 79(3):127–132

Gofton WT et al (2012) The Ottawa surgical competency operating room evaluation (O-SCORE): a tool to assess surgical competence. Acad Med 87(10):1401–1407

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed Siddiqui, N., Siddiqui, T., Shariff, A. et al. Availability of Operative Surgical Experience and Supervision for Competency-Based Education: A Review of A General Surgery Program at A Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital in Pakistan. World J Surg 46, 1849–1854 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-022-06571-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-022-06571-4