Abstract

Background

Surgery-related conditions account for the majority of admissions in primary referral hospitals in Sub-Saharan Africa. The role of surgery in the reduction of global disease burden is well recognized, but there is a great qualitative and quantitative disparity in the delivery of surgical and anaesthetic services between countries. This study aims at estimating the nature and volume of surgery delivered in an entire administrative division of Cameroon.

Methods

In this retrospective survey conducted during the year 2013, we used a standard tool to analyse the infrastructure and human resources involved in the delivery of surgical and anaesthetic services in the Fako division in the south-west region of Cameroon. We also estimated the nature and volume of surgical services as a rate per catchment population.

Results

Public, private and mission hospital contributed equally to the delivery of surgical services in the Fako. For every 100,000 people, there were <5 operative rooms. A total of 2460 surgical interventions were performed by 2.2 surgeons, 1.1 gynaecologists and 0.3 anaesthetists. These surgical interventions consisted mostly of minor and emergency procedures. Neurosurgery, paediatric, thoracic and endocrine surgery were almost non-existent.

Conclusions

The volume of surgery delivered in the Fako is far below the minimum rates required to meet up with the most basic requirements of the populations. It is likely that most of these surgical needs are left unattended. A community-based assessment of unmet surgical needs is necessary to accurately estimate the magnitude of the problem and guide surgical capacity improvements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The global burden of conditions potentially correctable by surgery is currently estimated to be 28–32 % [1–3]. Although the role of surgical services delivery in the reduction of disease burden has been established [4, 5], approximately 5 billion human beings currently still have no access to timely surgical care [1, 3]. There is a great qualitative and quantitative disparity in the delivery of surgical services between various countries and sometimes within the same country, and the burden of surgical conditions is known to disproportionately affect low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [1, 6, 7]. The disparity observed is generally related to differences in availability of human resources, inadequate/inappropriate infrastructure and equipment, poor health information system and limited financial resources for health in a context of a near-absent social security system amongst other factors [8–15]. Consequently, it is suspected that the nature and volume of surgical and anaesthetic services offered in Sub-Saharan African countries are generally below the real needs [7, 11, 16]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), death and disability can be greatly reduced in LMICs by timely basic surgical interventions such as caesarean sections, burn care or surgical treatment of fractures [2]. Data on the delivery of surgical services remain, however, scarce, and policies are mainly based on rough national estimates [8]. It is important to precisely estimate and analyse the specific situations and needs of individual countries. Without such estimates, it is difficult to optimize and tailor resources and interventions at the country level. In its 2015 core report, the Lancet Commission of Global Health has identified 6 surgical indicators for surgical system strengthening. These indicators include timely access to surgical services, availability of specialized workforce and surgical volume among others [3]. This study aimed at providing a comprehensive estimation of nature and volume of surgical and anaesthetic services offered to the population of an entire division of the south-west region of Cameroon. More specifically, we intended to propose a description of the characteristics of health institutions involved in the delivery of surgical services in the Fako division, analyse the strength of staff involved in delivering these services and estimate the volume of surgical and anaesthetic services offered per catchment population. The ultimate goal is to provide decision makers with information necessary for the planning of surgical care in terms of training, deployment of human resources and infrastructural development.

Methodology

Study design and setting

This retrospective survey covering the year 2013 (01st January 2013–31st December 2013) was carried out in the Fako division in the south-west region of Cameroon. This is a middle-income country located in central and western Africa with a gross domestic product per capita of 1328.64 us dollars. In 2013, the population was estimated at 22.25 million people with a life expectancy of 54.59 years (2013 World Bank estimate). The country is administratively divided into ten regions. The health centres constitute the portal of entry into the health care delivery system with the district hospitals as the primary referral level, the Regional hospitals the secondary referral and the National hospitals (national referral general hospitals, Central hospitals, University teaching hospitals) as tertiary referral level. There is no social health security system in Cameroon, and health insurance is almost non-existent. A fee-based system allows medical facilities to charge fees for services and treatment, with household financing for health care mostly done through out of pocket payment.

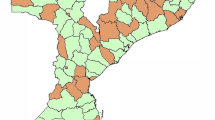

A map of the south-west region of Cameroon is shown in Fig. 2. Fako is one of the six divisions of the region and is located in the extreme south. Its total population was estimated at 527,525 people in 2013. The city of Buea located in the Fako is the administrative capital of the region (Fig. 1).

Data collection

This study was conducted according to principles of the Helsinki Declaration, and an ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Buea. All administrative authorizations were obtained from the Regional Delegation of Public Health for the south-west region. We developed a data collection tool (“Annex”) largely inspired by the PIPES tool used by Surgeons Overseas (SOSAS) and already validated for the assessment of delivery of surgical services in countries with similar characteristics [17, 18]. The tool was modified to meet with our objectives. This modified tool included data on the characteristics of the health facility, qualitative and quantitative estimation of human resources involved in delivery of surgical services within the facility and the nature and number of surgical and anaesthetic interventions carried out in the facility all through the year 2013.

The survey was conducted between 01st and 31st December 2014. With the collaboration of the Regional Delegation of Public Health in the south-west, we identified all health facilities in the Fako which delivered surgical and anaesthetic services during the year 2013. We then contacted the heads of these facilities by phone to schedule an appointment.

During each visit, after signing an informed consent form, the head of the institution was interviewed for data on characteristics of the institution and on information concerning human resources. We then reviewed all post-operative report documents for the number and type of surgical and anaesthetic procedures carried out during the study period. Every surgical procedure which had lasted 2 h or more and/or during which a natural cavity was explored and/or for which an hospitalization of at least 24 h was prescribed was recorded as a major procedure. All surgical procedures performed without any planning was recorded as an emergency procedure.

Data analysis and reporting

All data were entered in an MS excel (Microsoft Excel 2010, Microsoft corporation®) spread sheet and analysed using STATA 10 (STATA corps, Texas, USA). The STROBE guidelines were used in reporting this analysis [19].

Results

Infrastructure and human resources

A total of 19 health institutions which delivered surgical and/or anaesthetic services during the year 2013 were identified. From among these, 18 responded favourably to our request and were visited. These included 7 public hospitals, 7 private clinics, 3 mission hospitals and 1 corporate hospital. Table 1 summarizes the contribution of various types of hospital facilities to the work load in terms of infrastructure and human resources. The participating hospitals summed up a total 1274 admission beds and 26 operation rooms for a total catchment population of 527,525 people. This gave a ratio of 4.93 operation rooms for 100,000 people. The total number of admissions for the study period was 38,521 (7302/100,000 catchment population per year). There were 2.27 surgeons and 0.38 anaesthetic doctors available per 100,000 people during the study period.

Global surgical volume

A total of 12,977 procedures were carried out in these hospitals in 2013, giving a rate of 2460 operations/100,000 catchment population. As shown in Fig. 2, these procedures were most frequently minor procedures (59.2 %), often performed as an emergency. Figure 3 indicates the contribution of each type of institution in the total surgical workload and shows comparable contribution from public, private and mission hospitals.

The caesarean section rate as a ratio of total operations is often used as a proxy indicator for assessing surgical capacity and comparing the adequacy of surgical care between high- and low-income countries [20]. The total number of caesarean deliveries in our study was 1195. This represented a rate of 226.5/100,000 catchment population and 9.2 % of the total number of operations performed.

Types of procedures performed

Figure 4 analyses the surgical interventions performed according to the system or anatomical area of the body involved. Surgery in Fako was most frequently performed on skin and soft tissue. Most procedures recorded under urology were ritual circumcisions which represented 77.5 % of all procedures recorded under this system. Neurosurgery, thoracic and endocrine surgery represented 0.6, 0.7 and 0.06 % of the total number of procedures, respectively.

The type of anaesthesia performed was indicated for 10,592 (81.6 %) patients. As shown in Fig. 5, local anaesthesia was the most commonly performed anaesthetic procedure (38.6 %) and it appeared that 12.7 % of patients underwent surgery without any anaesthesia.

Listed in Table 2 are the ten most commonly performed operations identified in Fako division. As shown in this table, the 3 most common surgical procedures represented by wound suture, appendectomies and caesarean sections summed up to 3840 representing 29.6 % of all surgical interventions.

Discussion

Surgery-related conditions account for the majority of admissions, especially in primary referral hospitals in Sub-Saharan Africa [21].

This study is the first in Cameroon to propose a comprehensive estimation of surgical and anaesthetic services delivered in an entire administrative area of the country. Concerning the infrastructure, 19 health institutions in Fako propose surgery-related services and there are <5 operation rooms available for 100,000 people. The overall volume of surgical services delivered to the populations of the Fako division is estimated at 2460 surgical interventions per 100,000 people, most of which are minor procedures. According to available estimates, the expected number of procedures expected to meet up with the surgical needs per year is above 6000 [7, 16]. The caesarean section rate is as low as 9.2 % of all procedures as compared to 5–15 % often recommended by WHO [20]. These surgical services are delivered by 2.7 surgeons, 1.1 gynaecologists and 0.3 anaesthetists per 100,000 people. The Lancet Commission currently proposes a minimum of 20–40 surgeons/100,000 population. Consequently, general practitioners and anaesthetic nurses are heavily involved in the delivery of these specialized services. In Fako, public hospitals, private clinics and mission hospitals seem to contribute equally. Some specific surgical activities such as neurosurgery, thoracic and endocrine surgery are almost non-existent and notably significant proportion of surgical interventions is probably performed without any anaesthesia.

However, this report carries a number of limitations. It is likely that some institutions which actually carry out surgical activities in an unofficial background, especially health centres and some small-size private institutions were not included in the survey, with the likelihood that the volume of surgical services might have been consequently underestimated. It is well known that the reporting of surgical and other health care related activities is generally poor in Sub-Saharan and this contributes to the underestimation mentioned above [8, 22]. Also, it is questionable how generalizable our results are as major disparities have been previously reported between countries and sometimes within the same country [6, 14, 22–24].

The global volume of surgery and anaesthesia delivered in the Fako is about one-third of what has been estimated as necessary to address the health problems which are potentially curable by timely surgical intervention [7, 16]. When compared with available data from other LMICs, especially from Sub-Saharan Africa, although the literature on global surgical delivery is extremely scarce, available reports generally indicate a low surgical output at various rates [11, 25–29]. It has been estimated that <7 % of the global volume of surgery was performed in very low health expenditure countries which account for 37 % of the world’s population, while 60 % of the surgical volume took place in the high-expenditure countries which account for only 18 % of the world’s population [1]. Though caesarean section is often one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures, when used as an indicator of surgical delivery, its rate is still alarmingly low in many LMICs [11, 25, 27, 29, 30]. Also, the scope of surgical procedures performed is usually narrow and limited to emergency and life-saving procedures [11, 13, 25, 29, 31]. Up to 75 % of operations are usually performed as an emergency [13, 23, 25], and major surgery hardly exceeds 40 % of the overall surgical output [11, 32]. It has been reported that many health institutions at the district level in Sub-Saharan Africa were still not able to carry out the most basic surgical procedures such as hernia repair, appendectomy or a laparotomy [5, 15, 31]. On the other hand, the volume of specific surgical services such as orthopaedic surgery, neurosurgery, thoracic surgery and paediatric surgery is persistently reported as dangerously low [11, 27, 33–35]. In Cameroon, it has recently been shown that district hospitals are not equipped to provide basic life-saving procedures to injury victims in compliance with WHO guidelines [36].

One of the possible reasons to this low output is probably the major infrastructural failure described in most African countries despite recent minor improvements [4, 37]. The number of functioning operating rooms per catchment population usually fluctuates between 0.2 and <5 per 100,000 people [13, 24, 29]. This is probably why in some countries part of the workload is left to private and mission hospitals which sometimes display a better potential than governmental structures in terms of infrastructure, human resources and management [30, 38]. In our report, 3 mission hospitals could perform as well as 7 public hospitals in terms of volume of surgical services.

The second possible reason for this low surgical output is the total absence of a mechanism of financing the most basic surgical needs even in the context of extreme emergency. Affordability had been clearly identified as one of the major barriers to delivery of surgical services in Sub-Saharan African countries [28, 39–41].

The third possible reason is a major workforce crisis which has been reported in numerous LMICs [10, 12, 13, 15, 23, 24, 26, 42]. In a systematic review, Hoyler et al. estimated that across LMICs, general surgeon density ranged from 0.13 to 1.57 per 100,000 population, obstetrician density ranged from 0.042 to 12.5 per 100,000, and anaesthesiologist density ranged from 0 to 4.9 per 100,000 [8]. There is also a major disparity in terms of human resources between countries and sometimes within the same country, and the available trained health care providers usually work in large cities and referral hospitals [9–11, 24]. Consequently, surgical and anaesthetic services in the most remote areas tend to be delivered by unqualified staff with possible consequences on the quality of health care delivered [24, 42, 43]. This situation raises the need to discuss the possibility of officially shifting the performance of some selected surgical and anaesthetic procedures on non-medical personnel and reorganizing the training of health workers towards this objective. This must be particularly considered for anaesthesia as it is well known that anaesthetic interventions are often performed by nurses even at the regional or referral level [11, 24, 42–45]. Also, this problem could also be strategically addressed by encouraging the redeployment of available human resources towards rural areas through improvement of working conditions (technical settings, accommodation, remuneration, etc.).

Based on the above analysis, it can be accurately predicted that a large volume of the most basic surgical conditions in the Fako actually remains unattended. In a similar setting, it was recently estimated that up to 25 % of conditions potentially correctable by surgery are not taken care of and their contribution to death in households could be as high as 25 % [46, 47]. If hernia, the most frequently reported surgical condition in the world, is used as an example, it is estimated that 85 % of hernia cases in LMICs are not taken care of for various reasons [48]. It is also known that a significant fraction of these unattended surgical needs concern the musculoskeletal system, head and neck and paediatric surgery [33, 42, 49].

Conclusion

There is a major infrastructural failure in terms of number and quality of institutions delivering surgical and anaesthetic services, and the existing structures are probably underutilized. There is also a major workforce crisis, especially in the most remote areas where surgery and anaesthesia are often practiced by non-qualified health care providers. Consequently, most health conditions potentially correctable by surgery probably remain unattended.

The extent to which the overall low surgical and anaesthetic output in the Fako translate into unmet needs for services can only be estimated by a community-based assessment. In Cameroon in general, there is an acute need for systematically collected data at the national level to accurately and precisely estimate the real availability and effective utilization of infrastructure, the global volume of surgical and anaesthetic services delivered, the real workforce and the exact situation of surgery and anaesthesia health care providers. Further urgent research efforts should be directed towards obtaining these data. This would be in straight line with the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery—Global Indicator Initiative (LCoGS-GII) and the WHO global surgical workforce database. In the meantime, an improved utilization of existing infrastructure is possible by addressing some of the obstacle to the delivery of surgical and anaesthetic services. An urgent measure to achieve this goal would be the immediate implementation of a universal health insurance system. Measures to encourage the redeployment of existing qualified staff are also likely to rapidly improve the surgical output.

References

Shrime MG, Bickler SW, Alkire BC, Mock C (2015) Global burden of surgical disease: an estimation from the provider perspective. Lancet Global Health 27(3):S8

Debas HT, Donkor P, Gawande A et al (eds) (2015) Essential surgery: disease control priorities, vol 1, 3rd edn. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, Washington

Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L et al (2015) Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 386(9993):569–624

Mock C (2013) Confronting the global burden of surgical disease. World J Surg 37(7):1457–1459. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-2102-x

Kushner AL, Cherian MN, Noel L et al (2010) Addressing the Millennium Development Goals from a surgical perspective: essential surgery and anesthesia in 8 low- and middle-income countries. Arch Surg 145(2):154–159

Zafar SN, Fatmi Z, Iqbal A et al (2013) Disparities in access to surgical care within a lower income country: an alarming inequity. World J Surg 37(7):1470–1477. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1732-8

Rose J, Weiser TG, Hider P et al (2015) Estimated need for surgery worldwide based on prevalence of diseases: a modelling strategy for the WHO Global Health Estimate. Lancet Glob Health 3(Suppl 2):S13–S20

Hoyler M, Finlayson SR, McClain CD et al (2014) Shortage of doctors, shortage of data: a review of the global surgery, obstetrics, and anesthesia workforce literature. World J Surg 38(2):269–280. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-2324-y

Markin A, Barbero R, Leow JJ et al (2013) A quantitative analysis of surgical capacity in Santa Cruz, Bolivia. J Surg Res 185(1):190–197

Notrica MR, Evans FM, Knowlton LM et al (2011) Rwandan surgical and anesthesia infrastructure: a survey of district hospitals. World J Surg 35(8):1770–1780. doi:10.1007/s00268-011-1125-4

Chichom Mefire A, Atashili J, Mbuagbaw J (2013) Pattern of surgical practice in a regional hospital in Cameroon and implications for training. World J Surg 37(9):2101–2108. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-2116-4

Lebrun DG, Saavedra-Pozo I, Agreda-Flores F et al (2012) Surgical and anesthesia capacity in Bolivian public hospitals: results from a national hospital survey. World J Surg 36(11):2559–2566. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1722-x

Linden AF, Sekidde FS, Galukande M et al (2012) Challenges of surgery in developing countries: a survey of surgical and anesthesia capacity in Uganda’s public hospitals. World J Surg 36(5):1056–1065. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1482-7

Lebrun DG, Dhar D, Sarkar MI et al (2013) Measuring global surgical disparities: a survey of surgical and anesthesia infrastructure in Bangladesh. World J Surg 37(1):24–31. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1806-7

Iddriss A, Shivute N, Bickler S et al (2011) Emergency, anaesthetic and essential surgical capacity in the Gambia. Bull World Health Organ 89(8):565–572

Esquivel MM, Molina G, Uribe-Leitz T et al (2015) Proposed minimum rates of surgery to support desirable health outcomes: an observational study based on three strategies. World J Surg 39(9):2126–2131. doi:10.1007/s00268-015-3092-7

Gupta S, Ranjit A, Shrestha R et al (2014) Surgical needs of Nepal: pilot study of population based survey in Pokhara, Nepal. World J Surg 38(12):3041–3046. doi:10.1007/s00268-014-2753-2

Groen RS, Samai M, Petroze RT, Kamara TB, Yambasu SE, Calland JF, Kingham TP, Guterbock TM, Choo B, Kushner AL (2012) Pilot testing of a population-based surgical survey tool in Sierra Leone. World J Surg 36(4):771–774. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1448-9

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Initiative STROBE (2014) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 12(12):1495–1499

Petroze RT, Mehtsun W, Nzayisenga A et al (2012) Ratio of cesarean sections to total procedures as a marker of district hospital trauma capacity. World J Surg 36(9):2074–2079. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1629-6

Anderson JE, Erickson A, Funzamo C et al (2014) Surgical conditions account for the majority of admissions to three primary referral hospitals in rural Mozambique. World J Surg 38(4):823–829. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-2366-1

Nordberg E (1990) Surgical operations in eastern Africa: a review with conclusions regarding the need for further research. East Afr Med J 67(3 Suppl):1–28

LeBrun DG, Chackungal S, Chao TE et al (2014) Prioritizing essential surgery and safe anesthesia for the Post-2015 Development Agenda: operative capacities of 78 district hospitals in 7 low- and middle-income countries. Surgery 155(3):365–373

Petroze RT, Nzayisenga A, Rusanganwa V et al (2012) Comprehensive national analysis of emergency and essential surgical capacity in Rwanda. Br J Surg 99(3):436–443

Reshamwalla S, Gobeze AA, Ghosh S et al (2012) Snapshot of surgical activity in rural Ethiopia: Is enough being done? World J Surg 36(5):1049–1055. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1511-6

Nabembezi JS, Nordberg E (2001) Surgical output in Kibaale district, Uganda. East Afr Med J 78(7):379–381

Lavy C, Tindall A, Steinlechner C et al (2007) Surgery in Malawi—a national survey of activity in rural and urban hospitals. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 89(7):722–724

Patel HD, Groen RS, Kamara TB et al (2014) An estimate of hernia prevalence in Sierra Leone from a nationwide community survey. Hernia 18(2):297–303

Galukande M, von Schreeb J, Wladis A et al (2010) Essential surgery at the district hospital: a retrospective descriptive analysis in three African countries. PLoS Med 7(3):e1000243

Kingham TP, Kamara TB, Cherian MN et al (2009) Quantifying surgical capacity in Sierra Leone: a guide for improving surgical care. Arch Surg 144(2):122–127 (discussion 128)

Steinlechner C, Tindall A, Lavy C et al (2006) A national survey of surgical activity in hospitals in Malawi. Trop Dr 36(3):158–160

Abdullah F, Choo S, Hesse AA et al (2011) Assessment of surgical and obstetrical care at 10 district hospitals in Ghana using on-site interviews. J Surg Res 171(2):461–466

Petroze RT, Calland JF, Niyonkuru F et al (2014) Estimating pediatric surgical need in developing countries: a household survey in Rwanda. J Pediatr Surg 49(7):1092–1098

Van Buren NC, Groen RS, Kushner AL et al (2014) Untreated head and neck surgical disease in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional, countrywide survey. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 151(4):638–645

Groen RS, Samai M, Petroze RT et al (2013) Household survey in Sierra Leone reveals high prevalence of surgical conditions in children. World J Surg 37(6):1220–1226. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-1996-7

Chichom-Mefire A, Mbarga-Essim NT, Monono ME et al (2014) Compliance of district hospitals in the Center Region of Cameroon with WHO/IATSIC guidelines for the care of the injured: a cross-sectional analysis. World J Surg 38(10):2525–2533. doi:10.1007/s00268-014-2609-9

Merchant A, Hendel S, Shockley R et al (2015) Evaluating progress in the global surgical crisis: contrasting access to emergency and essential surgery and safe anesthesia around the world. World J Surg 39(11):2630–2635. doi:10.1007/s00268-015-3179-1

Funk LM, Conley DM, Berry WR et al (2013) Hospital management practices and availability of surgery in sub-Saharan Africa: a pilot study of three hospitals. World J Surg 37(11):2520–2528. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-2172-9

Stewart BT, Gyedu A, Abantanga F et al (2015) Barriers to essential surgical care in low- and middle-income countries: a pilot study of a comprehensive assessment tool in Ghana. World J Surg 39(11):2613–2621. doi:10.1007/s00268-015-3168-4

Ilbawi AM, Einterz EM, Nkusu D (2013) Obstacles to surgical services in a rural Cameroonian district hospital. World J Surg 37(6):1208–1215. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-1977-x

Kwon S, Groen RS, Kamara TB et al (2013) Nationally representative household survey of surgery and mortality in Sierra Leone. World J Surg 37(8):1829–1835. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-2035-4

Kruk ME, Wladis A, Mbembati N et al (2010) Human resource and funding constraints for essential surgery in district hospitals in Africa: a retrospective cross-sectional survey. PLoS Med 7(3):e1000242

Henry JA, Windapo O, Kushner AL et al (2012) A survey of surgical capacity in rural southern Nigeria: opportunities for change. World J Surg 36(12):2811–2818. doi:10.1007/s00268-012-1764-0

Burke T, Manglani Y, Altawil Z et al (2015) A safe-anesthesia innovation for emergency and life-improving surgeries when no anesthetist is available: a descriptive review of 193 consecutive surgeries. World J Surg 39(9):2147–2152. doi:10.1007/s00268-015-3118-1

McQueen K, Coonan T, Ottaway A et al (2015) The bare minimum: the reality of global anaesthesia and patient safety. World J Surg 39(9):2153–2160. doi:10.1007/s00268-015-3101-x

Groen RS, Samai M, Stewart KA et al (2012) Untreated surgical conditions in Sierra Leone: a cluster randomised, cross-sectional, countrywide survey. Lancet 380(9847):1082–1087

Wong EG, Kamara TB, Groen RS et al (2015) Prevalence of surgical conditions in individuals aged more than 50 years: a cluster-based household survey in Sierra Leone. World J Surg 39(1):55–61. doi:10.1007/s00268-014-2620-1

Grimes CE, Law RS, Borgstein ES et al (2012) Systematic review of met and unmet need of surgical disease in rural sub-Saharan Africa. World J Surg 36(1):8–23. doi:10.1007/s00268-011-1330-1

Elliott IS, Groen RS, Kamara TB et al (2015) The burden of musculoskeletal disease in Sierra Leone. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 473(1):380–389

Acknowledgments

The authors are extremely grateful to the directors and chief executive of all hospitals and health institutions who accepted to contribute to this important survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Annex

Annex

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chichom-Mefire, A., Mbome Njie, V., Verla, V. et al. A Retrospective One-Year Estimation of the Volume and Nature of Surgical and Anaesthetic Services Delivered to the Populations of the Fako Division of the South-West Region of Cameroon: An Urgent Call for Action. World J Surg 41, 660–671 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-016-3775-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-016-3775-8