Abstract

Background

Different studies performed on nasal subunit reconstruction by either the nasolabial flap or the paramedian forehead flap have reported contradictory outcomes and complications, claiming one flap or the other as superior. This inconsistency has led to a gap in existing literature regarding the preferable flap for nasal reconstruction. Our aim was to statistically evaluate and compare these two flaps for nasal reconstruction, in terms of subunit preference, complications, and outcomes, using data from previous studies.

Methods

This systematic review is reported using PRISMA protocol and was registered with the International prospective register of systematic reviews. The literature search was done using "paramedian forehead flap", "nasolabial flap", "melolabial flap", "nasal reconstruction". Data regarding demography of study and population, subunit reconstructed, complications, and aesthetic outcomes were extracted. Meta-analysis was performed using MetaXL and summary of findings using GRADEpro GDT.

Results

Thirty-eight studies were included, and data from 2036 followed-up patients were extracted for the review. Meta-analysis was done on data from nine studies. Difference in alar reconstruction by forehead versus nasolabial flap is statistically significant [pooled odds ratio (OR) 0.3; 95% CI 0.01, 0.92; p = 0.72; I2 = 0%, n = 6 studies], while for dorsum and columella reconstruction the difference is not statistically significant. Risk of alar notching is marginally more in forehead flap, however difference in incidence of partial/complete flap necrosis, alar notching and hematoma/bleeding among the flaps is not statistically significant.

Conclusion

Alar reconstruction is preferred by nasolabial flap. Complications are similar in both groups. Comparison of aesthetic outcome needs further exploration.

Level of Evidence III

This journal requires that authors assign a level of evidence to each article. For a full description of these Evidence-Based Medicine ratings, please refer to the Table of Contents or the online Instructions to Authors www.springer.com/00266.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

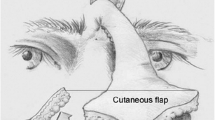

Nasal defects occur following excision of tumors, namely Basal cell carcinoma, Squamous cell carcinoma, melanomas, sarcoma, lymphomas, sweat gland carcinoma and other benign/inflammatory growth, trichoepithelioma, arteriovenous malformations, rhinophyoma; trauma; insect, animal or human bite; post burns (thermal, electrical, chemical); skin necrosis following radiotherapy, sepsis; cosmetic removal of various skin lesions, nevi; congenital craniofacial deformities.

A wide variety of flaps have been devised for nasal defect reconstruction depending upon the nasal subunit(s) involved, extent and size and the layers involved. However, the paramedian forehead flap and the nasolabial flap have been explored far more than other reconstruction modalities, hence they may be considered the workhorse for nasal defect reconstruction. The proponents of either flap had enumerated various pearls and pitfalls of their flaps. Some authors have also compared the two flaps in their studies [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. But more often their outcomes and conclusions were not coherent to one another.

Our primary objective was to estimate the frequency of each type of nasal subunit being reconstructed with either the paramedian forehead flap or the nasolabial flap, and also the incidences of various post-operative complications in each group. Our secondary objective was to determine the relative risk of various complications among both the groups of flap reconstruction. The complications included partial or total flap necrosis, alar notching, hematoma or bleeding, following reconstruction with either these flaps.

Materials and Method

Search Strategy

This systematic review was registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO), adhering to the standards of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. An electronic database search on PubMed, Google Scholar and the Cochrane Library was conducted on December, 2020 using a combination of both Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and plain text related to nasal reconstruction. Studies limited to humans and published in English language were searched since inception. The syntax used for search strategy was as follows:

PubMed: ("paramedian forehead flap") OR ("nasolabial flap") OR ("melolabial flap") OR ("nasal reconstruction").

The Cochrane Library: "paramedian forehead flap" in Title Abstract Keyword OR "nasolabial flap" in Title Abstract Keyword OR "melolabial flap" in Title Abstract Keyword OR "nasal reconstruction" in Title Abstract Keyword.

Google Scholar: "paramedian forehead flap" OR "nasolabial flap" OR "melolabial flap" OR "nasal reconstruction" (excluding patents and citations).

The manuscripts were reviewed manually by two independent authors (SSC, NS) to identify appropriate studies. Duplicate studies were removed. References of appropriate articles were also screened to identify additional related studies. Predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) were applied for eligibility for inclusion. In case of any discrepancy, a consensus was formed by mutual discussion with other reviewers.

Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers (SA, AKM) extracted the data independently from the included studies in a standardised Data Extraction sheet for various parametersusing Microsoft® Excel®. In case of any discrepancy, a consensus was formed by mutual discussion with other reviewers. The data extracted includes demographic details (Title, authors, country of origin, year of publication, type of study, level of evidence), population details (Total number of patients, number of males/females, number of flaps done and followed-up, patients’ age, comorbidities and addiction), perioperative details (Flaps performed, with any modifications, defect size, subunit reconstructed, follow-up duration), outcomes (Functional outcomes measured by methods like questionnaire, NAFEQ scores, quality of speech, total nasal function; Aesthetic outcomes assessed by questionnaire, visual analog scale, pigmentation, contour deformity, Derriford Appearance Scale 24, height, colour etc.),and complications (necrosis, dehiscence, pin cushioning, hematoma, infection, scar contracture, congestion, notching, revision surgery, donor morbidities).

Statistical Analysis

Two review authors (ADG, SSC) analysed data. The weighted mean of each outcome was calculated based on sample sizes of each included study using the following method: (1) multiply the mean outcome of each study by the study sample size, (2) sum the products to get the total value, (3) sum the sample sizes to get the total weight, and (4) divide the total value by the total weight to provide a weighted mean for each outcome. The meta-analysis was performed using the Microsoft® Excel® 2016, with MetaXL version 5.2, add-in software (developed by EpiGear International Pty Ltd). The summary effect was ascertained using Odds Ratio (OR) which was calculated using the Inverse Variance Heterogenity model. Heterogeneity was ascertained using the I squared statistic. Small study effects like publication bias were evaluated using the Doi plot and Luis Furuya-Kanamori (LFK) index. High heterogeneity in the summary effect was further explored using sensitivity analysis. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

Evidence Certainty

The certainty of evidence for the systematic review was assessed by two independent reviewers (ADG, NS) using the GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool [Software]. McMaster University and Evidence Prime, 2021. Available from gradepro.org. In case of any discrepancy, a consensus was formed by mutual discussion with other reviewers.

Results

Summary of Study and Patient Demography

The electronic database search produced 16,698 results. After title and abstract review 124 citations were identified (Fig. 1), that were considered for full text review. Thirty-eight articles [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] met our inclusion/exclusion criteria. The other 86 studies were either case reports; or less than 10 patients were followed-up; or complications/outcomes were not recorded independently for the reconstructed flaps; or variations of the forehead/nasolabial flaps have been used. Twenty-seven studies were retrospective, while one study was prospective (Table 2). Out of total 2652 patients in these studies, 2036 patients were followed-up, in which 1443 underwent reconstruction with paramedian forehead flap. In the forehead flap group reported male and female patients were 425 and 399 respectively, while in nasolabial flap group this was 150 and 208 respectively. The weighted mean age of patients in the forehead and nasolabial group is 66.63 and 64.91 yearsrespectively. The weighted mean follow-up in the groups is 10.7 and 21.9 months respectively.

Summary of Flap Demography

Twenty-six studies have reported the relative number of nasal subunits that were reconstructed with either forehead or nasolabial flaps (Supplementary Table 1). Forehead flap was most commonly used for reconstruction of alar defects, immediately followed by sidewall, tip and dorsum (Table 3). Nasolabial flap was predominantly used for alar reconstruction. Our Meta-analysis shows a statistically significant difference in the incidence of alar reconstruction by forehead versus nasolabial flap [pooled odds ratio (OR): 0.3; 95% CI 0.01, 0.92; p = 0.72; I2 = 0%, n = 6 studies] (Fig. 2). To analyse the impact of individual studies on the pooled estimate a sensitivity analysis was done. On excluding the study of Vasalikis et al. [6], it is found that the pooled OR is not significant statistically, anymore (95% CI 0.14, 2.43) (Table 4). The meta-analysis done on incidence of dorsum and columella reconstruction by these flaps shows that the pooled odds ratios are not significant statistically [pooled OR for dorsum reconstruction: 5.97; 95% CI 0.99, 35.95; p = 0.61; I2 = 0%; n = 3 studies and pooled OR for columellar reconstruction: 1.84; 95% CI 0.35, 9.67; p = 0.4; I2 = 0%; n = 4 studies] (Fig. 2). Although, the study of Vasalikis et al. [6] and of Yoon et al. [7] appears outlier for dorsum and columella respectively, the sensitivity analysis performed shows that even on omitting the studies the pooled OR obtained is not significantly different from the overall pooled estimates [pooledOR: 3.02; 95% CI 0.32, 28.4; p = 0.96; I2 = 0%; n = 3 studies; and pooled OR: 4.77; 95% CI 0.65, 35.15; p = 0.37; I2 = 0%; n = 4 studies respectively] (Table 4).

Summary of Complications and Outcomes

The incidence of complications following nasal reconstruction with nasolabial or forehead flap was reported by 36 studies (Supplementary table 2). The frequency of pin cushioning effect, thick/bulky scar,pigmentation, and subsequent steroid injection seemed more common in forehead flap reconstruction than nasolabial flap, while in the latter nasal obstruction seemed more frequently present (Table 3). All other complications were comparable in both groups. Meta-analysis was performed over data from 9 observational studies [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] which have reported the relative incidences of complications of both flaps, or the relative number of the nasal subunits reconstructed. Our meta-analysis shows that there is no significant difference in the risk of partial flap necrosis in the forehead flap vs nasolabial flap [pooled OR 1.28; 95% CI 0.46–3.53; p = 0.7; I2 = 0%, n = 6 studies] (Fig. 3). On visual inspection, the study by Uzun et al. [9] appears to be an outlier with OR 9.89 (95% CI 0.17, 560.85). However, on excluding this study the pooled OR is 1.117 (95% CI 0.392, 3.183) which is not significantly different from the overall pooled estimate (p = 0.739) (Table 5). The difference in the risk of complete flap necrosis in-between these flaps is also not significant statistically [pooled OR 1.28; 95% CI 0.19–8.39; p = 0.67; I2 = 0%, n = 4 studies] (Fig. 3). Again, the study by Uzun et al. [9] seems an outlier with OR 9.89 (95% CI 0.17, 560.85). However, on excluding this study the pooled OR is 0.721 (95% CI 0.086, 6.070) which is not significantly different from the overall pooled estimate (p = 0.862) (Table 5). There is no significant difference in the risk of alar notching also [pooled OR 1.81; 95% CI 0.55–5.91; p = 0.27; I2 = 0%, n = 4 studies] (Fig. 3). Here the study by Han et al. [8] appears an outlier with OR = 10.00 (95% CI 0.58, 171.2). On excluding this study, the pooled OR is not significantly different from the overall pooled estimate [OR: 1.453; 95% CI 0.460, 4.59; p = 0.309; I2 = 14.85; n = 4 studies] (Table 5). There is no significant difference in the risk of hematoma/bleeding in the forehead flap vs nasolabial flap [OR 2.04; 95% CI 0.34–12.81; p = 0.79; I2 = 0%, n = 4 studies] (Fig. 3). Although the study by Uzun et al. [9] seems an outlier with OR 9.89 (95% CI 0.17, 560.85), on excluding this study the pooled OR is not significantly different [OR: 1.38; 95% CI 0.19, 10.18; p = 0.85; I2 = 0.0; n = 4 studies] (Table 5). Five studies have compared the paramedian forehead and nasolabial flaps used for nasal reconstruction in terms of functional and aesthetic outcomes of donor and recipient sites [1, 3,4,5, 8]. We refrained from performing meta-analysis of other complications and the outcomes due to paucity of uniform level of information.

Publication Bias

The Doi plot with LFK index of the subunit reconstructions (dorsum, alae, columella) (Fig. 4) and the complications (partial or complete flap necrosis, alar notching, hematoma or bleeding) (Fig. 5) shows no or minor asymmetry. This suggests that there is no publication bias and small study effects, which may be affecting the results of meta-analysis done.

Evidence Certainty

The certainty of evidence assessed for the various outcomes as per GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) criteria are of lowcertainty category. The summary of findings table shows a mild increased risk difference of complications with paramedian forehead flap than the nasolabial flap (Table 6).

Discussion

In our review, based on 38 studies, we found that ala is the most commonly reconstructed subunit. Seven studies were dedicated for alar reconstruction [1, 3, 4, 8, 18, 28, 36], four of which [1, 3, 4, 8] have compared the nasolabial flap and paramedian forehead flap for alar reconstruction in their studies. Most of the nasolabial flaps (melolabial is an anatomically more precise description) [13] have been used for alar reconstruction in comparison to other subunits, which is not the case with forehead flap (Table 3). Our meta-analysis shows that there is increased propensity of alar reconstruction by nasolabial versus forehead flap, which is statistically significant. Vasalikis et al. [6] suggested larger alar reconstruction to be done using nasolabial flap, while tip and dorsal defects > 1.5 cm using forehead flap. However, our meta-analysis shows that there is no significant difference in the incidence of dorsal or columellar reconstructions by either flap. The I2 values in Forest plot shows that there is no heterogeneity in these studies (Fig. 2).

We were not able to find any relation of the nasal defect size with either flap type used for reconstruction, due to heterogeneity in the information of the studies. In the algorithm suggested by Uzun et al. [9], nasolabial flaps are preferred for lateral defects in middle or lower third, while forehead flap reconstruction for distal 2/3rd or combined defects. Based on their study of 17 nasal defects’ reconstruction, Han et al. [8] suggested that for a full thickness defect, that is > 2 cm, forehead flap is preferred. While for defects < 2 cm nasolabial flap reconstruction is preferred. In 2001, Drisco and Baker [4] suggested forehead flap reconstruction for nasal alar defects > 1.5 cm, young patient with inconspicuous melolabial fold and cheek involvement, while in other alar defects interpolated cheek flap is preferred. In their follow-up of 83 nasal reconstructions, Vasilakis et al. [6] reported statistically significant difference in the size of the defects (p < 0.001), in their greater diameter, in-between the groups. However, all these studies were retrospective so they would be prone to selection bias.

Our meta-analysis shows that there is no statistically significant difference in the risk of complications (partial or total flap necrosis, alar notching, hematoma/bleeding) in-between the groups. Overall, there is no heterogeneity in most of these studies (Fig. 3). However, in our summary of findings table it seems that there is mild increased risk of alar notching in case of paramedian forehead flap (Table 6). Paddack et al. [2], with a follow-up of 25 nasolabial and 82 paramedian forehead flaps, found that diabetes, hypertension, coronary arterial disease, COPD and smoking were not statistically significant factors in flap failure, although in the latter flap failure shows an increasing trend.

In 1999, Arden et al. [1] in a follow-up of 20 forehead flaps and 18 melolabial flaps for alar reconstruction reported that objective scar measurements (rim thickness difference, donor scar length and width), subjective rating of textural quality, and post-operative alar notching favoured melolabial reconstructions. Patient’s questionnaire results demonstrated a statistically significant (p = 0.026) difference in donor site rating, favouring melolabial group responses. While in 2019, Genova et al. [3] reported that for alar reconstruction forehead flaps gave statistically better aesthetic and functional results (p = 0.03 for both variable) than nasolabial flaps, according to patient satisfaction survey, after a mean follow-up period of 2.3 years. Forehead flaps also had superior alar contour, telangiectasia/erythema, post-operative scar, alar and nostril symmetry from basilar view, compared to nasolabial flaps, according to Surgeons’ questionnaire (comprising of all 5 above variables, each scored as 1–3). Sherris et al. [5] recorded better aesthetic results after forehead flap reconstruction than nasolabial flap, 5.5 versus 4.4 respectively (change on a 1–10 Visual Analog Scale from defect to after reconstruction) for columellar defects. However, due to small group size, authors refrained from any statistical analysis. Drisco and Baker [4] found on a scale of 1–3 that forehead flap reconstruction seemed better in terms of breathing self-assessment, patient result, and observer result of scar and overall. We were not able to perform any meta-analysis on the overall aesthetic outcome from the data of these studies, as different scales for measurement were used.

Despite our sincere efforts there were certain limitations in this study. Statistical significance of the difference in cosmetic and functional outcomes of the paramedian forehead and nasolabial flaps could not be calculated because the included studies have used different parameters and scales to assess them. Meta-analysis of many outcome complications (infection, dehiscence, congestion, pin cushioning, nasal obstruction etc.) and few subunit reconstructions (nasal tip and sidewall) could not be done due to inadequate data. The included studies have different follow-up periods. The variations in nasolabial flap, namely interpolated, islanded flaps, or in forehead flaps, namely 2- or 3-staged flaps, included in our review might be a limitation in our results. Most of the studies in the review are retrospective and some are prospective which could have affected the results. Lastly, confounding factors such as age, gender, co-morbidities of patients, dimension and extent of the flap or the defect etc could not be taken into account due to absence of individual data.

Conclusion

We conclude that for the alar subunit, reconstruction using the nasolabial (melolabial) flap is significantly preferable than the paramedian forehead flap. This does not hold true for other subunits. There is an inclination to reconstruct larger defects by forehead flap. The difference in the risk of complications in the post operative period in either group is statistically insignificant, though there is a mild increased risk in the forehead flap group. The aesthetic outcomes among the groups compared by the studies are contradictory to each other and needs further exploration.

References

Arden RL, Nawroz-Danish M, Yoo GH, Meleca RJ, Burgio DL (1999) Nasal alar reconstruction: a critical analysis using melolabial island and paramedian forehead flaps. Laryngoscope 109(3):376–382

Paddack AC, Frank RW, Spencer HJ, Key JM, Vural E (2012) Outcomes of paramedian forehead and nasolabial interpolation flaps in nasal reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 138(4):367–371

Genova R, Gardner PA, Oliver LN, Chaiyasate K (2019) Outcome study after nasal alar/peri-alar subunit reconstruction: comparing paramedian forehead flap to nasolabial flap. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 7(5):e2209

Driscoll BP, Baker SR (2001) Reconstruction of nasal alar defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 3(2):91–99. Erratum in: Arch Facial Plast Surg 2001 Oct–Dec; 3(4). Drisco BP [corrected to Driscoll BP]

Sherris DA, Fuerstenberg J, Danahey D, Hilger PA (2002) Reconstruction of the nasal columella. Arch Fac Plast Surg 4(1):42–46

Vasilakis V, Nguyen KT, Klein GM, Brewer BW (2019) Revisiting nasal reconstruction after mohs surgery: a simplified approach based on the liberal application of local flaps. Ann Plast Surg 83(3):300–304

Yoon T, Benito-Ruiz J, García-Díez E, Serra-Renom JM (2006) Our algorithm for nasal reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 59(3):239–247

Han DH, Mangoba DC, Lee DY, Jin HR (2012) Reconstruction of nasal alar defects in Asian patients. Arch Facial Plast Surg 14(5):312–317

Uzun H, Bitik O, Kamburoğlu HO, Dadaci M, Çaliş M, Öcal E (2015) Assessment of patients who underwent nasal reconstruction after non-melanoma skin cancer excision. J Craniofac Surg 26(4):1299–1303

Dhawan IK, Aggarwal SB, Hariharan S (1974) Use of an off-midline forehead flap for the repair of small nasal defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 53(5):537–539

Conley JJ, Price JC (1981) The midline vertical forehead flap. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 89(1):38–44

Zitelli JA (1990) The nasolabial flap as a single-stage procedure. Arch Dermatol 126(11):1445–1448

Younger RA (1992) The versatile melolabial flap. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 107(6 Pt 1):721–726

Klingensmith MR, Millman B, Foster WP (1994) Analysis of methods for nasal tip reconstruction. Head Neck 16(4):347–357

Quatela VC, Sherris DA, Rounds MF (1995) Esthetic refinements in forehead flap nasal reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 121(10):1106–1113

Uchinuma E, Matsui K, Shimakura Y, Murashita K, Shioya N (1997) Evaluation of the median forehead flap and the nasolabial flap in nasal reconstruction. Aesthet Plast Surg 21(2):86–89

Konz B, Worle B, Sander CA (1997) Aesthetic reconstruction of nasal defects using forehead flaps. Fac Plast Surg 13(2):111–117

Lindsey WH (2001) Reliability of the melolabial flap for alar reconstruction. Arch Fac Plast Surg 3(1):33–37

Park SS (2002) The single-stage forehead flap in nasal reconstruction: an alternative with advantages. Arch Fac Plast Surg 4(1):32–36

Ullmann Y, Fodor L, Shoshani O, Rissin Y, Eldor L, Egozi D, Ramon Y (2005) A novel approach to the use of the paramedian forehead flap for nasal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 115(5):1372–1378

Thornton JF, Weathers WM (2008) Nasolabial flap for nasal tip reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 122(3):775–781

Little SC, Hughley BB, Park SS (2009) Complications with forehead flaps in nasal reconstruction. Laryngoscope 119(6):1093–1099

Angobaldo J, Marks M (2009) Refinements in nasal reconstruction: the cross-paramedian forehead flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 123(1):87–93

Yu D, Weng R, Wang H, Mu X, Li Q (2010) Anatomical study of forehead flap with its pedicle based on cutaneous branch of supratrochlear artery and its application in nasal reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg 65(2):183–187

Jones DC (2011) The paramedian forehead flap in the reconstruction of nasal defects: 50 consecutive cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 40(10):E4

Somoano B, Kampp J, Gladstone HB (2011) Accelerated takedown of the paramedian forehead flap at 1 week: indications, technique, and improving patient quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol 65(1):97–105

Ribuffo D, Serratore F, Cigna E, Sorvillo V, Guerra M, Bucher S, Scuderi N (2012) Nasal reconstruction with the two stages vs three stages forehead flap: a three centres experience over ten years. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 16(13):1866–1872

Arden RL, Miguel GS (2012) The subcutaneous melolabial island flap for nasal alar reconstruction: a clinical review with nuances in technique. Laryngoscope 122(8):1685–1689

Monarca C, Rizzo MI, Palmieri A, Chiummariello S, Fino P, Scuderi N (2012) Comparative analysis between nasolabial and island pedicle flaps in the ala nose reconstruction. Prospective study. In Vivo. 26(1):93–98. Erratum in: In Vivo. 2012 Jul–Aug;26(4):741–742

Kendler M, Averbeck M, Wetzig T (2013) Reconstruction of nasal defects with forehead flaps in patients older than 75 years of age. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 28(5):662–666

de Pochat VD, Alonso N, Ribeiro EB, Figueiredo BS, de Magaldi EN, Cunha MS, Meneses JV (2014) Nasal reconstruction with the paramedian forehead flap using the aesthetic subunits principle. J Craniofac Surg 25(6):2070–2073

Stahl AS, Gubisch W, Haack S, Meisner C, Stahl S (2015) Aesthetic and Functional outcomes of 2-stage versus 3-stage paramedian forehead flap techniques: a 9-year comparative study with prospectively collected data. Dermatol Surg 41(10):1137–1148

Sanniec K, Malafa M, Thornton JF (2017) Simplifying the forehead flap for nasal reconstruction: a review of 420 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 140(2):371–380

Mughal A, O’Grady K, Kamissetty A, Jones C (2017) An investigation of patient recorded outcomes following nasal reconstruction with paramedian forehead flaps. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 55(10):105

Orangi M, Dyson ME, Goldberg LH, Kimyai-Asadi A (2019) Repair of apical triangle defects using melolabial rotation flaps. Dermatol Surg 45(3):358–362

Noel W, Duron JB, Jabbour S, Revol M, Mazouz-Dorval S (2018) Three-stage folded forehead flap for nasal reconstruction: objective and subjective measurements of aesthetic and functional outcomes. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 71(4):548–556

Rudolph MA, Walker NJ, Rebowe RE, Marks MW (2019) Broadening applications and insights into the cross-paramedian forehead flap over a 19-year period. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 72(5):763–770

Lo Torto F, Redi U, Cigna E, Losco L, Marcasciano M, Casella D, Ciudad P, Ribuffo D (2020) Nasal reconstruction with two stages versus three stages forehead fap: what is better for patients with high vascular risk? J Craniofac Surg 31(1):e57–e60

Acknowledgements

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights, or Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chakraborty, S.S., Goel, A.D., Sahu, R.K. et al. Effectiveness of Nasolabial Flap Versus Paramedian Forehead Flap for Nasal Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Aesth Plast Surg 47, 313–329 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-022-03060-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-022-03060-w