Abstract

Background

The purpose of this review is to examine a single surgeon’s 10-year experience with nose defects and offer a simplified approach for nasal reconstruction to close most nasal defects following Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS).

Patients and Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed on patients undergoing repair of MMS defects of the nose over a 10-year period. Data collected included patients’ age and sex, anatomic location of the defect, type of reconstruction, and number of operations required.

Results

A total of 419 patients were included in this study. The most common location for nasal reconstruction was the nasal dorsum and sidewalls (66.35 %). Complications mainly related to reconstruction of defects of the tip ± ala (n = 31), followed by the ala (n = 15) and the dorsum and sidewalls (n = 13). Bulkiness of the flap used (n = 32) and hypertrophic scar (n = 13) were the most common complications. The bilobed flap was the most commonly used flap (n = 145), followed by nasolabial flap (n = 69), FTSGs (n = 63), forehead flap (n = 62), and dorsal glabellar flap (n = 44).

Conclusions

In this article, a simplified approach for nasal defects reconstruction is presented, which is based on commonly performed local flaps and skin grafting. This algorithm can be useful for the novice plastic surgeons in planning a reconstructive strategy that will be efficient, easy to perform, and produces an acceptable esthetic and functional outcome.

Level of Evidence IV

This journal requires that authors assign a level of evidence to each article. For a full description of these Evidence-Based Medicine ratings, please refer to the Table of Contents or the online Instructions to Authors http://www.springer.com/00266.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Following the advent of Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) [1], skin cancers are being aggressively treated successfully but leave defects that often require reconstruction. Moreover, the nose, due to its central location in the face, may be the most difficult facial feature to reconstruct well.

Contemporary nasal reconstruction embraces concepts of esthetic units and a diligent and meticulous repair of all internal lining deficits [2]. The bar for nasal reconstruction has been raised to a new level where patients can realistically hope for an esthetic outcome that becomes inconspicuous to the general public and a functional result that is normal and taken for granted.

Application of the esthetic unit principles provides a logical cognitive approach to nasal reconstruction [3]. Missing tissue must be replaced with like tissue at a quantity and quality that exactly replicates the pattern, surface area, and contour of the absent unit [4]. Reconstructive options range from skin grafts to complex free-tissue transfer [2, 5–9].

Nasal reconstruction can be a daunting task for many surgeons, especially the novice surgeon or surgeon in training. The purpose of this review is to examine a single center’s 10-year experience with nose defects and offer a simplified approach for nasal reconstruction to close most nasal defects following MMS.

Patients and Methods

Study Population

A retrospective chart review was performed on patients undergoing repair of MMS defects of the nose at our center over a 10-year period. The study protocol has been approved by the appropriate institutional and/or national research ethics committee and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All the patients signed a consent form prior to the reconstruction.

Inclusion criteria included (1) age ≥18 years old; (2) patients underwent prior to reconstruction a MMS for skin malignancy of the nose; (3) patients did not undergo reconstruction elsewhere; (4) a local or a regional flap or a skin graft was used for reconstruction; and (5) follow-up ≥2 years.

Planning

Nasal defects are classified according to size, anatomic location, and depth. Defects ≤0.5 cm can be closed primarily. Superficial defects ≤1.5 cm in diameter with an intact cartilaginous framework are usually amenable to local flap or skin graft reconstruction. Defects >1.5 cm are less likely to be successfully closed with local flaps and often require either interpolated flaps for closure or full-thickness skin grafts (FTSGs).

When the defect involves >50 % of the subunit, the defect is modified in accordance with the subunit principle to camouflage scars within natural creases or at borders of 2 subunits. However, this is not universally applicable, as enlarging small defects may result in increased use of the forehead flap for defects where smaller local flaps may suffice [10, 11].

When the tissue defect involves the skin and the cartilaginous and/or bony framework of the nose as well, then both the soft tissue and structural defects should be repaired. Cartilage can be harvested from the ear or septum if a septoplasty is planned.

Most nasal-lining defects require repair with pedicled soft tissue flaps or FTSGs. When local flaps are unavailable, lining can be reconstructed using regional or distant tissue. For subtotal or total nasal reconstruction with multiple layers involved, major multistep reconstruction should be carried out. An algorithm for nasal defects reconstruction is provided in Table 1.

Techniques

A Bilobed flap (modified by Zitelli) is used for defects located between 0.5 and 1.5 cm of the distal and lateral aspect of the nose, particularly defects involving the ala with intact alar rim, the lateral tip, supratip, or tissue near the tip, which range up to 1.5 cm in size. The bilobed flap can be used with a cartilage graft in patients at risk for nasal valve collapse.

A Nasolabial flap is utilized as a two-stage procedure for partial and full-thickness alar defects with diameters between 1.5 and 2.0 cm. The flap is designed at least 1–2 mm larger in all dimensions to allow for postoperative contraction. Three weeks later, the flap inset is partially elevated, and placement of cartilage grafts, to prevent scar contraction, can be performed as necessary.

The Forehead flap is a two-stage reconstruction which is indicated for either alar defects >2.0 cm in diameter, defects involving the tip and the ala, or large nasal defects. During the second stage, three weeks after the flap elevation, thinning of the flap and cartilage grafts are performed as necessary. After division of the flap, the unused part of the flap is excised.

A Glabellar flap is indicated for defects of the middle and upper third of the nose, which are ≤2.0 cm. The flap can be used as a rotation or advancement flap.

Advancement flaps are used in repair of medium and large defects in the nasal dorsum and sidewalls. Advancement flaps from the cheek are usually employed for such defects.

FTSGs are indicated for large defects in high-risk patients who cannot tolerate general anesthesia for more complex procedures, and those who require close surveillance for recurrence of malignancy. FTSG can also be used in a delayed fashion, following development of granulation tissue over the defect.

Internal lining Intranasal mucosal flaps are the preferred method for many full-thickness defects because they replace tissue with like tissue. Another option is the application of FTSGs to the deep raw surface of the flap used for repair of the defect.

Revisions Ancillary procedures are used, as needed, for enhancement of functional and esthetic outcomes.

Data Analysis

Data collected included patients’ age and sex, anatomic location of the defect, type of reconstruction, and number of operations required. Demographic characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 2. Due to the large size of the study population, anatomic locations of the nasal defects are grouped as ala, dorsum and sidewalls (including lateral tip, supratip, or tissue near the tip), and tip ± ala. The nasal reconstructions were analyzed by type of reconstruction used.

Results

A total of 419 patients were included in this study. There were 186 male and 233 female patients. The most common nasal defect was the nasal dorsum and sidewalls (66.35 %). The mean age of the patients was 69.8 years (standard deviation ± 13.6 years). The mean follow-up was 5.07 years (standard deviation ± 2.46 years). Ear cartilage grafts were used for reconstruction of framework defects of the lower nose. In Table 3, reconstructions are summarized according to sex and anatomic locations. In Table 4, the cases in which a combination of techniques was used are summarized according to sex and anatomic location.

Ala There were 74 patients with ala defects (17.67 %). In 69 patients, out of 74, a nasolabial flap was used, a FTSG (n = 5) (Fig 1a–f) in the rest of the cases. The nasolabial flap was used as a sole reconstruction in 30 cases. The nasolabial flap was combined with a cartilage graft (n = 35), with a cartilage graft and an advancement flap (n = 2), with an advancement flap (n = 1) and with a bilobed flap (n = 1) (Fig 2a–e), respectively.

A 62-year-old Caucasian female with a left nasal ala and lower lateral nasal sidewall defect. The patient denied reconstruction with a forehead flap. The lower lateral cartilage was not involved in the defect. A full-thickness skin graft from the left supraclavicular area was used for the reconstruction. a Preoperative lateral view of the defect. b Preoperative antero-posterior view of the defect. c Postoperative antero-posterior view of the reconstruction at 6 months

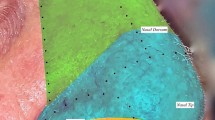

Dorsum and sidewalls There were 278 patients with dorsum and sidewalls defects (66.34 %). The bilobed flap was used in 145 patients, out of 278. The bilobed flap was combined with a cartilage graft (n = 7) and with a FTSG (n = 2), respectively. In 44 patients, a dorsal glabellar flap was used. In 8 patients, a combination of a dorsal glabellar flap with either a FTSG (n = 5), or an advancement flap (n = 2) or a cartilage graft (n = 1), was used respectively. An advancement flap was used in 32 cases. In 5 cases, the advancement flap was combined with a FTSG. In 5 cases, out of 278, another flap was selected.

Tip ± ala There were 67 patients with tip ± ala defects (15.99 %). In 62 patients, out of 67, a forehead flap was used (Fig 3a–f) and a FTSG (n = 5) for the rest of the cases. In 26 patients, out of 62, the forehead flap was used as a sole reconstruction. The forehead flap was combined with a cartilage graft (n = 32), with a cartilage graft and a FTSG (n = 3) and with an advancement flap (n = 1), respectively.

A 49-year-old Caucasian female with a right ala defect which also involved the underlying cartilage. A right paramedian forehead flap and an auricular cartilage graft were used for the reconstruction. a Preoperative lateral view of the defect. b Intraoperative markings of the forehead flap. c Postoperative antero-posterior view of the reconstruction at 5 years

Internal lining (Table 5) There were 47 cases in which internal lining reconstruction was performed. The defects were located in the ala (n = 11) and in the tip ± ala (n = 36). In 23 cases, the folded distal part of the forehead flap was used as internal lining. Mucosal flaps were used for internal lining repair in 17 patients. FTSGs were used in 4 patients and the nasolabial flap in 3 cases, respectively.

Complications–Revisions

Complications and revisions are summarized according to sex and anatomic location in Tables 6 and 7, respectively. Complications occurred in 59 patients (14.08 %). Complications mainly related to reconstruction of defects of the tip ± ala (n = 31), followed by the ala (n = 15) and the dorsum and sidewalls (n = 13). Bulkiness of the flap used (n = 32) and hypertrophic scar (n = 13) were the most common complications. Flap bulkiness was mainly associated with forehead flaps (n = 19) followed by the nasolabial flap (n = 7). Flap thinning (n = 32) and scar excision (n = 13) were the most common revision procedures performed.

Discussion

A successful nasal reconstruction is characterized by good contrast between the nose and its surroundings, an inconspicuous border scar, a good color, and texture match with the surrounding skin and bilateral symmetry [3, 12]. The surgeon must accurately assess not only the defect, but also the patient [13]. The patient should also have an active role in the decision making, particularly if it involves undertaking a complex multistage procedure.

Although a wide range of techniques have been described, repair of Mohs defects can be challenging for reconstructive surgeons because of size or location of the defect, or both [14]. Confirming a simplified and reliable algorithm for nasal reconstruction will be useful to residents in training and the novice surgeon in practice. This algorithm should narrow choices to allow for a quicker and simpler treatment selection, realizing that there is always more than one method of reconstruction.

After reviewing our experience, we have devised a treatment algorithm with which the majority of nasal defects can be reconstructed with one of five techniques: FTSG, bilobed flap, nasolabial flap, forehead flap, or dorsal glabellar flap. In the current series, 91.41 % of the defects (n = 383) were reconstructed using one of the aforementioned techniques.

Bilobed flaps are best suited for defects ranging up to 1.5 cm, in the distal half of the dorsum, in sidewalls, in the lateral tip, and supratip areas [15]. It has the advantages of being a single-stage flap of simple design that has excellent color and texture match with adjacent tissues and predictable flap viability [16]. Among its disadvantages are that it has complex incision lines, cannot follow the principle of nasal subunit reconstruction, is limited to closure of small nasal defects, and has a dramatic ability to distort the symmetry of the distal nose if not planned appropriately [15].

Moy et al. [17] concluded that the bilobed flap is an excellent choice for reconstruction of defects of the lower nose because of the good skin match and low incidence of complications. Ibrahim et al. [14] suggested that the bilobed flap is the workhorse for the nasal ala, tip, and side wall. In the current series, the bilobed flap was for defects of the distal nasal dorsum and sidewalls and the lateral tip and supratip areas, respectively. If the bilobed flap is used for central tip defects, it can cause tip contour distortion.

The glabellar flap has traditionally been described as a V–Y advancement flap based on a random blood supply for the reconstruction of defects of the upper third of the nose; however, multiple modifications of the procedure have been described [18]. The glabellar flap can easily be performed, leading to decreased risk to the patient and increased convenience. Moreover, it uses local skin that is of similar texture, consistency, and color to that of the defect. The donor-site defect can be closed primarily in most cases, and the incisions and resultant scars are generally well camouflaged [18]. On the other hand, closure of the donor-site defect can lead to narrowing of the interbrow distance. In the current series, the glabellar flap was used in 44 cases for defects of the proximal half of the dorsum and sidewalls.

A FTSG is generally not considered the ideal replacement for nasal skin, in particular, for the thick, sebaceous skin of the nasal tip, ala, lower sidewalls, or dorsum. The basic concern with using a skin graft is the resultant patchwork appearance caused by color mismatch and contour defects [8]. However, there are occasions where a FTSG represents the ideal method of repair with respect to optimal esthetic outcome. This is particularly true for the fair-skinned individual with a superficial defect involving the upper third of the nose [19].

McCluskey et al. [20] reported that skin grafting of defects of the caudal third of the nose offers a viable reconstructive option that yields good contour and color match. In patients who are very poor surgical candidates, the defect may be best repaired with a single-stage procedure which can be either a FTSG or a local flap. In the current series, FTSGs were used in 63 patients as a main reconstruction procedure. It was mainly used for defects of the nasal sidewalls and dorsum (n = 53, 84.13 %).

The nasolabial flap is a well-known versatile procedure, which provides a reliable source of skin and the further possibility of reconstruction for large defects, and is one of the most recommended choices [21]. It is the ideal reconstructive modality for alar defects. It can also be used for internal lining defects when septal mucosal flaps are not available or for large lining defects. Good outcomes can be attained with either defect-only or subunit approaches [13]. Moreover, the donor-site scar can be well hidden in the existing nasolabial crease.

Disadvantages include the possibility of blunting the alar groove and a high risk for pin cushioning if the flap is not sized appropriately. Moreover, without meticulous suturing technique, the rounded scar, where the flap insets at the ala, tends to invert [22].

Bloom et al. [22] suggested that the nasolabial flap, when applied to properly selected nasal defects, should enable the surgeon to achieve a final reconstruction result that closely approximates the preinjury state while producing limited donor-site deformity. In the current series, a two-stage nasolabial flap was used for ala defects ≤2.0 cm in 69 cases. Although complications occurred in 9 cases (out of 69, 13.04 %), none of them was considered major.

Another option for ala defects ≤1.5 cm is the auricular chondrocutaneous composite graft with which it is possible to reconstruct the structural cartilage along with the inner mucosa and outer skin reconstruction in one stage [23]. However, it is not used frequently because it may cause postoperative deformity of the donor site and reduced survival rate of the graft [24]. Although varied approaches to improving survival have been proposed, evidence-based standards for optimal graft management have not been widely disseminated [25]. Graft survival has also been shown to be adversely affected by smoking [26]. In the current series, auricular composite grafts had not been used due to factors related to patients’ denial, medical comorbidities (e.g., smoking), or size of the defect.

The forehead flap remains the standard technique for large nasal defects. It can be used for resurfacing the entire nose, from ala to ala. Its dependability and consistent anatomy make the forehead flap a workhorse for major nasal restoration, setting the bar for an esthetically inconspicuous reconstruction and restoration of function [27]. The donor-site morbidity is acceptable, including when one allows any residual defect to heal by second intention.

Because forehead skin is thicker than nasal skin, thinning of the flap is required. Although aggressive thinning of the distal part of the skin paddle of the forehead can be safely accomplished [28], forehead flap bulkiness is a common postoperative complication [29].

Little et al. [29] reported a retrospective chart review of 205 patients who had forehead flap reconstruction in a 13-year period, in which 16.1 % of the patients developed a major complication (including flap necrosis, nasal obstruction, and alar notching). In the current series, the forehead flap was used for tip ± ala defects in 62 patients. Additional thinning of the forehead flap skin paddle was performed in 19 cases (30.64 %), and there were no cases of partial necrosis.

Defects of the lateral and inferior nose are often reinforced with autogenous cartilage grafts to prevent sidewall collapse, as well as cephalic soft tissue retraction [20] and thus maintaining optimal three-dimensional reconstruction. Moreover, there are a number of different flaps available for reconstituting the internal lining, and one must be facile with many of them. Flap selection may be influenced by the size of the defect, other unrelated lesions, and ischemic factors. Intranasal mucosal flaps are the workhorse for many internal lining defects and have the advantage of a robust vascularity while representing thin and “physiologic” tissue [2]. In the current series, internal lining reconstruction was performed in 47 cases, with forehead flaps and mucosal flaps to be the most common techniques performed.

It is interesting to note that, in our series, there is a clear predilection of female patients, even though it is well known in the literature that skin cancers tend to occur more often in male patients, especially on the nose [30]. Furthermore, whereas experiences from most plastic surgeons would indicate that distal nasal defects are encountered more commonly, in our series, the dorsum and sidewalls were the most frequently involved areas.

The proposed algorithm narrows choices and allows for a quicker and simpler treatment selection, especially for the younger surgeon in the early part of his or her professional practice. The suggested algorithm, in comparison to others [31, 32], is based on limited and easy to perform techniques, which can be performed under local anesthesia and in an outpatient setting, and covers all the range of defects. Moreover, this algorithm can also be valid for nasal defects due to trauma.

There are some limitations to this study that should be discussed. Although many algorithms have been proposed regarding nasal reconstruction [31, 32], comparison is difficult due to different classifications of nose defects and the variability of types of reconstruction used. Moreover, selection of the optimal reconstructive approach is always affected by racial, cultural, and socioeconomic factors and the patients’ need and concerns. Thus, although an algorithmic approach for nasal reconstruction may simplify the decision making regarding reconstruction, an individualized treatment approach is always the key for optimal functional and esthetic results.

Conclusions

In this article, a simplified approach for nasal defects reconstruction is presented, which is based on commonly performed local flaps and skin grafting. This algorithm can be useful for the novice plastic surgeons in planning a reconstructive strategy that will be efficient, easy to perform, and produces an acceptable esthetic and functional outcome.

References

Bowen GM, White GL Jr, Gerwels JW (2005) Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician 72(5):845–848

Park SS (2008) Nasal reconstruction in the 21st century: a contemporary review. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 1(1):1–9

Burget GC, Menick FJ (1985) The subunit principle in nasal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 76(2):239–247

Asaria J, Pepper JP, Baker SR (2010) Key issues in nasal reconstruction. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 18(4):278–282

Parrett BM, Pribaz JJ (2009) An algorithm for treatment of nasal defects. Clin Plast Surg 36(3):407–420

Fischer H, Gubisch W (2008) Nasal reconstruction: a challenge for plastic surgery. Dtsch Arztebl Int 105(43):741–746

Rohrich RJ, Griffin JR, Ansari M, Beran SJ, Potter JK (2004) Nasal reconstruction-beyond aesthetic subunits: a 15-year review of 1334 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 114(6):1405–1416 discussion 1417–1419

Salgarelli AC, Bellini P, Multinu A, Magnoni C, Francomano M, Fantini F, Consolo U, Seidenari S (2011) Reconstruction of nasal skin cancer defects with local flaps. J Skin Cancer 2011:181093. doi:10.1155/2011/181093

Antunes MB, Chalian AA (2011) Microvascular reconstruction of nasal defects. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 19(1):157–162

Singh DJ, Bartlett SP (2003) Aesthetic considerations in nasal reconstruction and the role of modified nasal subunits. Plast Reconstr Surg 111(2):639–648

Menick FJ (2003) Aesthetic considerations in nasal reconstruction and the role of modified nasal subunits. Plast Reconstr Surg 111(2):649–651

Millard DR Jr (1976) Reconstructive rhinoplasty for the lower two-thirds of the nose. Plast Reconstr Surg 57:722–728

Thornton JF, Griffin JR, Constantine FC (2008) Nasal reconstruction: an overview and nuances. Semin Plast Surg 22(4):257–268

Ibrahim AM, Rabie AN, Borud L, Tobias AM, Lee BT, Lin SJ (2014) Common patterns of reconstruction for mohs defects in the head and neck. J Craniofac Surg 25(1):87–92

Steiger JD (2011) Bilobed flaps in nasal reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 19(1):107–111

Chu EA, Byrne PJ (2009) Local flaps I: bilobed, rhombic, and cervicofacial. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 17(3):349–360

Moy RL, Grossfeld JS, Baum M, Rivlin D, Eremia S (1994) Reconstruction of the nose utilizing a bilobed flap. Int J Dermatol 33:657–660

Koch CA, Archibald DJ, Friedman O (2011) Glabellar flaps in nasal reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 19(1):113–122

Park SS (2000) Reconstruction of nasal defects larger than 1.5 centimeters in diameter. Laryngoscope 110(8):1241–1250

McCluskey PD, Constantine FC, Thornton JF (2009) Lower third nasal reconstruction: when is skin grafting an appropriate option? Plast Reconstr Surg 124(3):826–835

Turan A, Kul Z, Türkaslan T, Ozyiğit T, Ozsoy Z (2007) Reconstruction of lower half defects of the nose with the lateral nasal artery pedicle nasolabial island flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 119(6):1767–1772

Bloom JD, Ransom ER, Miller CJ (2011) Reconstruction of alar defects. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 19(1):63–83

Son D, Kwak M, Yun S, Yeo H, Kim J, Han K (2012) Large auricular chondrocutaneous composite graft for nasal alar and columellar reconstruction. Arch Plast Surg 39(4):323–338

Lehman JA Jr, Garrett WS Jr, Musgrave RH (1971) Earlobe composite grafts for the correction of nasal defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 47:12–16

Harbison JM, Kriet JD, Humphrey CD (2012) Improving outcomes for composite grafts in nasal reconstruction. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 20(4):267–273

Woodard C, Park S (2011) Reconstruction of nasal defects 1.5 cm or smaller. Arch Facial Plast Surg 13:97–102

Oo KK, Park SS (2011) The midline forehead flap in nasal reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 19(1):141–155

Chang JS, Becker SS, Park SS (2004) Nasal reconstruction: the state of the art. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 12(4):336–343

Little S, Hughley BB, Park SS (2009) Complications with forehead flaps in nasal reconstruction. Laryngoscope 119:1093–1099

Smeets NW, Kuijpers DI, Nelemans P, Ostertag JU, Verhaegh ME, Krekels GA, Neumann HA (2004) Mohs’ micrographic surgery for treatment of basal cell carcinoma of the face: results of a retrospective study and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol 151:141–147

Guo L, Pribaz JR, Pribaz JJ (2008) Nasal reconstruction with local flaps: a simple algorithm for management of small defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 122(5):130e–139e

Moolenburgh SE, McLennan L, Levendag PC, Munte K, Scholtemeijer M, Hofer SO, Mureau MA (2010) Nasal reconstruction after malignant tumor resection: an algorithm for treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg 126(1):97–105

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Konofaos, P., Alvarez, S., McKinnie, J.E. et al. Nasal Reconstruction: A Simplified Approach Based on 419 Operated Cases. Aesth Plast Surg 39, 91–99 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-014-0417-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-014-0417-0