Abstract

Introduction

In recent years, cryolipolysis (CLL), a noninvasive approach based upon the inherent sensitivity of adipocytes to cold injury, has emerged. However, it is not clear whether available evidence to date about its efficacy justifies aggressive marketing and extensive widespread application by many practitioners without well-defined indications or objectives of treatment. The current review is intended to evaluate available evidence regarding CLL mechanisms of action and its efficacy not only in fat reducing but also in its ability to result in an aesthetically optimal outcome.

Materials and Methods

A systematic search of PubMed and Scopus computerized medical bibliographic database was conducted with the search terms “cryolipolysis,” “lipocryolysis,” and “cool sculpting.” Selection criteria included all matched reports with the search terms in their titles.

Results

Thirty-two reports matched the inclusion criteria of this review. Five experimental studies were identified and included to further supplement the discussion.

Conclusion

Most reports about CLL included in this review lacked rigorous scientific methodology in study design or in outcome measurement. Serious concerns about integrity of many of these reports, particularly with respect to validity of photographic outcome documentation in addition to objectivity, conflict of interest issues, and commercial bias, have been expressed. Further research should be encouraged to prove with methodological rigor positive effects of this treatment modality and to determine categories of patients in whom most favorable outcomes might be expected.

Level of Evidence III

This journal requires that authors assign a level of evidence to each article. For a full description of these Evidence-Based Medicine ratings, please refer to the Table of Contents or the online Instructions to Authors www.springer.com/00266.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Body contouring and fat removal have become staples of the cosmetic market and are increasingly popular procedures with a worldwide rising demand [1, 2, 3, 4]. Conventional fat removal can be effectively achieved by liposuction; however, despite being generally safe, liposuction carries undoubtedly certain risks, costs, and downtime [5]. Given its invasive nature, interest in innovative noninvasive fat reduction modalities is growing [5] and research for the development of safe and effective techniques is ongoing [2, 6]. Various energy sources, such as laser, ultrasound, infrared light, and radiofrequency, have been suggested with reported variable efficacy [2, 4, 7]. In recent years, cryolipolysis (CLL), a noninvasive approach based upon the inherent sensitivity of adipocytes to cold injury, has emerged. With controlled cooling, selective destruction of fat cells can be achieved without damaging surrounding tissues and without significant change in serum lipids levels or liver function tests [8, 9]. Anecdotally, the impression that cold exposure could damage subcutaneous fat tissue came from the observation of “popsicle panniculitis,” a rare type of cold-induced fat necrosis in infant’s cheek fat, and “equestrian panniculitis” another uncommon clinical entity [3, 7, 9]. US FDA clearance of the technology was obtained in 2010 and 2012 for fat reduction on the flank and abdomen. Recently, CLL is being applied in various parts of the body including upper and lower extremities, the buttocks, and submental area [3, 9].

In spite of being a new technology without a fully understood mechanism of action, promising results of CLL have been confirmed by experimental animal models and reported in numerous clinical studies [2, 8, 10]. Research on CLL has been growing and new evidence is emerging [11]. The latest systematic reviews show that reduction in the adipose layer may approach 30% per treated region [11, 12, 13, 14]. Currently, CLL is presented as the gold-standard noninvasive technique for subcutaneous fat reduction [4]. However, it is not clear whether available evidence to date about its efficacy justifies extensive widespread application by many practitioners without well-defined indications or objectives of treatment. The current review is intended to evaluate available evidence regarding CLL mechanisms of action and its efficacy not only in fat reducing but also in its ability to result in an aesthetically optimal outcome

Materials and Methods

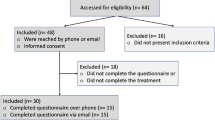

To identify experimental and clinical studies or case reports assessing mechanism of action and outcomes of cryolipolysis, a systematic search of PubMed and Scopus computerized medical bibliographic database was conducted with the search terms “cryolipolysis,” ”lipocryolysis,” and “cool sculpting.” Selection criteria included all matched reports with the search terms in their titles.

Inclusion criteria for this review were reports with original data, randomized controlled trials, and prospective or retrospective cohort studies with outcome measures. Letters-to-the-editor and commentaries without abstracts were excluded same as reviews, case reports, and reports about management of CLL complications or about comparative studies of combination therapies where CLL was not the prime therapy investigated. Studies comparing different CLL applicators or systems were also excluded.

Results

Primary literature search revealed 173 publications with titles including one of the search terms; 42 letters-to-the-editor and short communications were excluded. All abstracts of identified reports were retrieved and screened for eligibility. Thirty-four reports matched the inclusion criteria of this review (Table1). Five experimental studies were identified and included in this review to further supplement the discussion (Table 2). One report in Spanish and another one in German, though matching the inclusion criteria as judged by their English abstracts, were excluded.

Discussion

Tissues can be irreversibly damaged by heat extraction and freeze/ thaw cycles as experienced with clinical cryosurgery [7]. There is evidence that adipose tissue is preferentially sensitive to cold injury, and studies suggest that temperatures as high as 1 °C can decrease adipocytes viability. With controlled cold application to the skin surface, selective damage to subcutaneous fat with preservation of dermis viability can be achieved [6, 7, 15, 16].

CLL safety and efficacy have been claimed in numerous clinical reports and case series studies; however, as evident from the current literature review, most suffer from serious methodological flaws, such as non-randomization with no comparator group. Moreover, most these reports fall short of setting clear treatment objectives besides reducing subcutaneous fat layer in the targeted areas and none considered the standard of care to which any new body sculpturing modality must be compared [17]. Many authors are also clinical advisors or sponsored by CLL equipment manufacturers [6, 7, 9, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22] a source of obvious conflict of interest and bias [11].

Little scientific evidence about efficacy of CLL has been published; important links of the mode of action and physiological changes that may lead to fat reduction are still not yet fully understood [18, 23]. Two main mechanisms have been proposed. Selective acute heat extraction induces panniculitis; inflammation results in adipocyte apoptosis, a decisive factor for fat layer reduction over a period of 4 to 6 weeks after treatment, or adipose tissue loss could be induced by thermogenic fat metabolism without cell disruption [8, 24].

Four experimental animal studies investigating the effect of CLL were identified by this literature search [6, 7, 16, 18]. A time line of histologic changes over 3 months after cold exposure in a pig animal model with different cooling devices has been described by Manstein et al. [7] documenting selective damage with subsequent loss of subcutaneous fat confined to the superficial fat–dermis interface without epidermis, dermis nor underlying muscle tissue injury. Despite some variation in serum lipid levels over time following CLL, Kwon et al. [6] noted that their levels remained within the bounds of normal. They suggested as well that cooling devices could affect lipid catabolism and activate endogenous lipid metabolites through the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) pathway.

For their part Pinto et al. [18] demonstrated that when exposed to cold, lipids inside adipocytes undergo physical crystallization, a necessary step for unleashing apoptotic stimulus; however, they could not provide correlation between crystallization that may be permanent and lipid-to-gel transition overlapping nor could they determine whether injury to adipose tissue could be the result of apoptotic pathways activation or actual cellular damage and necrosis nor whether this effect is immediate or delayed. The authors noted, rightly so, that variations in lipid composition and ratio of mono- and poly-unsaturated and saturated fatty acids that have different lipid-to-gel transition and crystallization temperatures, may have profound clinical implications regarding effectiveness of various CLL protocols. Outcome may also be affected by crystal size that differs with cooling temperatures and duration of exposure [18].

Fat cooling takes time. More than 3 min are needed for the superficial fat to reach 10 °C at the dermis–fat interface [7]. An interesting software simulation recently described provided qualitative understanding of how temperature varies within tissues. It demonstrated that temperature drop in deeper subcutaneous layers is not very consistent and reduction in thickness of these layers is not to be expected [1].

In vivo adipocyte histologic changes in human subjects have been investigated only in few clinical studies. CLL to the lower abdomen in a patient candidate to have an abdominoplasty was reported by Meyer et al. [2]. A blinded pathologist observed fibrosis, adipocytes lysis and areas with localized infiltrates and macrophages suggesting an inflammatory state. Reduction in the fat layer thickness was also observed by both histology and US evaluations. The study of Boey et al. [25] demonstrated increasing inflammatory response in similar abdominoplasty specimens excised at various intervals following CLL, peaking at 30 days with dense inflammatory infiltrate and reduction of adipocyte size. Subsequently, inflammation decreased at 60 and 120 days with further reduced adipocyte size. Pugliese et al. [8] have moved with this study methodology a step further. They evaluated the effects of a single standard application of CLL in 6 patients. A blinded pathologist performed histological examination of tissue biopsies. Described histopathology was somewhat comparable to what has been demonstrated by other investigators. However, this study indicated that the gradual process of apoptosis lasts longer than the peak described earlier. It was still observed 60 days after CLL treatment and probably would exceed this period. Moreover, some differences in capillary vasculature were evident at the advanced stages of the observation period indicative of a reparative process with reticular architectural changes in areas of apoptosis with widespread involvement of the stromal scaffolding of the subcutaneous tissues.

Among the plethora of repots about favorable clinical results, a recent randomized controlled trial with a blinded assessor and well-controlled methodology of CLL application and outcome measurement, evaluating the effects of one single session of CLL on the subcutaneous adipose layer thickness of the lower abdomen [11] stands alone against the current trend and is the first reliable study to report an unfavorable outcome. Adipose layer thickness evaluation of the study and control groups was performed 15 days prior to CLL application and then 30, 60, and 90 days thereafter. Investigators could not demonstrate any significant difference between the 2 groups. The high level of evidence of this well-conducted study should seriously question current practices.

Reporting of CLL clinical outcomes has focused mainly on degree of fat reduction and has been primarily assessed by means of circumference measurements, caliper measurements, ultrasound, patient satisfaction questionnaires, and observer impressions that are all subject to bias. Currently, there are no objective, noninvasive, quantitative, reliable, and practical techniques to measure changes in the subcutaneous fat layer [26]. Caliper measurements are unlikely to be sufficiently precise for reliable comparisons, and ultrasound imaging is affected by pressure on the transducer [17, 24]; both are operator dependent. More reliable techniques such as high-resolution ultrasound and MRI are cumbersome in the outpatient setting and are associated with high costs [26]. Interpretation of pre- and post-treatment photographic documentation is highly subjective and cannot be a reliable tool for comparison particularly when changes are in the order of few millimeters. Moreover, monitoring treatment response over time over a period not less than few months during which weight gain or loss may have happened is also not very accurate. Several investigators have reported results relying on correct identification of baseline clinical photographs by independent reviewers as a proof of efficacy [19, 27] as if a change from pre-treatment state indicates a good outcome. Three-dimensional (3D) imaging to analyze volume reduction independently of observer impression and patient satisfaction scores is a newly introduced assessment tool that could bring some objectivity to outcome measurement even though it does not totally eliminate operator error [24]. Its utilization, however, is still very limited.

Best optimistic reports about CLL do not claim more than 21% favorable results following 1 CLL application to the abdomen and fat layer reduction of 17.4% to 20.4% after 2 months and 21.5% to 25.5% after 6 months of treatment to other areas [11, 28]. Some, however, have reported less than 5% improvement 6 weeks post-treatment judged by independent evaluators [29], while others did not find any benefit with CLL treatment of the thighs buttocks and knees but claim 23% fat reduction following abdomen, back, and flank treatment [30]. Regardless of the significance and validity of reporting results as % improvement, when examining actual reduction in thickness, cost-to-benefit value of a method that actually reduces fat thickness by 2.5 mm in 16 weeks should raise serious questions [31]. Carruthers et al. [32] reported 3.2-mm fat layer reduction on the upper arms, and Zelickson et al. [16] reported 2.8 mm reduction on the inner thigh. Submental fat layer reduction of 2.0 mm is also reported [10]. In some reports, conclusions are not even supported by presented data. While reporting in a split-body study that 57% of male patients treated by CLL for gynecomastia were slightly satisfied with the treated breast, and although overall satisfaction was not significance, Jones et al. [33] concluded that CLL is effective in reducing the mean adipose tissue thickness in male breasts. It is difficult to imagine how clinically significant three-dimensional body sculpturing that requires fat removal from deep and superficial layers and from confluent areas, could be achieved with such minimal changes in the superficial subcutaneous fat layer that would only become evident 3 months after treatment. Despite somewhat obvious fat reduction, demonstrated CLL treatment aesthetic results in publications are mostly suboptimal and in some patients are frankly objectionable [19, 24, 29]. Better results could have been achieved almost immediately with liposuction and with reasonable downtime. Definitely, as conceded by Sasaki et al. [29], CLL does not match liposuction that remains the gold standard for body sculpturing to which other modalities should be compared.

There is no need to argue whether CLL induces adipocyte apoptosis and cellular death or not and how much fat tissue layer can be reduced; in the final analysis, the main concern should be how effective this treatment modality is in meeting patients’ expectations and in producing a harmonious aesthetically pleasing outcome. No clear answer to this crucial question was provided by any of the investigators reviewed. Munavalli et al. [21], while admitting to the modest improvement that could be achieved with CLL treatment of male gynecomastia, stated that patients reported significant improvement in quality of life with less embarrassment. Obviously, cognitive dissonance makes it difficult for patients to admit to themselves that they have spent money on an ineffective treatment as rightly said by Swanson [17]. Instead of attracting patients with the noninvasive nature of the modality and its hypothetical expected % reduction in circumference or in fat layer thickness that may be irrelevant if not misleading, patients should be allowed to decide and be able to make an informed consent based on solid evidence provided by controlled blinded clinical studies about body sculpturing outcome with CLL compared to that of liposuction, the gold standard for body contouring.

It should be mentioned that numerous CLL equipment are available from different manufacturers with various applicators and application protocols. Till today, there is no consensus in the literature regarding the most appropriate equipment and the ideal CLL treatment protocol regarding parameters of the device, periodicity, and number of sessions required per body region [11, 12, 14]. Moreover, it is still not clear what is the patients’ BMI range for which a reasonably favorable outcome may be expected [5, 11, 25, 34, 35].

The good safety profile is one of the advantages of noninvasive CLL [10]; it is not, however, painless or entirely without risk. Besides disappointing, asymmetrical or unfavorable results, serious skin necrosis, though rare, has been reported. Redness, bruising, discomfort, and temporary numbness are common; nodules can also occur [17, 31, 36, 37]. Paradoxical adipose hyperplasia is another complication most commonly reported in men [38].

Skin tightening is another factor to be considered besides fat layer reducing when evaluating outcome of any body contouring procedure. Though CLL has not been recognized as a skin-tightening procedure, skin adherence to new body contour and firmness has been observed in patients with previous flaccidity. It occurs in a verifiable way according to some authors in 25% of cases [2, 8, 39]. It is believed that cryolipolysis delivers a cold-based thermal insult to the skin, which similar to insult caused by heat-based therapy, chemical peels, microneedling, or filler injections, results in fibrosis and skin tightening [32]. Vacuum applicators used for delivery of most CLL treatments pull a tissue bulge into the treatment cup; this results in mild stretching and could be a contributing factor as well to neocollagenesis [32]. It is still not known however how predictable is skin-tightening. It is not known also how it may be affected by patient’s age, skin condition, and BMI [39]. Claim of skin tightening based on very few patients without objective and valid outcome assessment cannot hold up to scientific scrutiny [17].

Conclusion

Since beauty is mostly subjective, assessing aesthetic surgery novel procedures and outcomes is difficult; the notion of success largely depends on ill defined subjective rather than objective measurements [24]. It is true that plastic surgeons need to listen to their “inner Michelangelo” [40] and “be innovators, pioneers, creators, visionaries, and communicators, not only scientists” [41], unfortunately, in vaunting the merits of noninvasive alternatives to liposuction, commercial acceptance has largely outpaced scientific scrutiny [17, 42]. Excluding few experimental and clinical experiences, most reports about CLL included in this review lacked rigorous scientific methodology in study design or in outcome measurement. Serious concerns about integrity of many of these reports, particularly with respect to validity of photographic outcome documentation in addition to objectivity, conflict of interest issues, and commercial bias, have been expressed [31]. In some of these reports, it is difficult to appreciate the change due to CLL nor to distinguish the before and after images. In other reports, the after images do not demonstrate pleasant optimal and aesthetic outcomes despite some evident fat reduction. An unhappy disillusioned patient is not a source of professional satisfaction and certainly will not help to gain attention and build a practice; with it comes physician demoralization, which may be a cause of physician burnout as warned by Swanson [40].

Despite lack of solid evidence, new methods even with questionable scientific foundation deserve our close attention. Claimed potential benefit of CLL should not be dismissed lightly. At the same time, it is unethical to use an innovative procedure as powerful selling point to patients without valid scientific proof. Innovation and creativity are celebrated in our specialty; however, we need to be cautious and question without hesitation claims of some investigators who may have an evident conflict of interest. Moreover, before considering any new treatment modality or novel device, principles of evidence-based medicine should not be overshadowed by tempting financial benefits. Rethinking these principles is not an option. Sound scientific basis and solid evidence of clinical efficacy empower us as service providers and are not incompatible with a thriving practice in a highly competitive surgical and medical cosmetic domain [40].

To claim that CLL is a noninvasive technique that could be a good alternative to liposuction in patients with moderate excess fat as claimed by some [4] is not justified. Certainly further research should be encouraged to prove with methodological rigor positive effects of this treatment modality and to determine categories of patients in whom most favorable outcomes might be expected. It must be kept in mind, however, that mere fat layer reduction is not and should not be the main goal of any body contouring modality; it is rather achieving 3D harmonious body shape to our satisfaction as well as to that of patients.

References

Majdabadi A, Abazari M (2016) Simulation of cryolipolysis as a novel method for noninvasive fat layer reduction. Turk J Med Sci 46:1682–1687

Meyer PF, da Silva RM, Oliveira G, Tavares MA, et al (2016) Effects of cryolipolysis on abdominal adiposity. Case Rep Dermatol Med 2016:6052194

Oh CH, Shim JS, Bae KI, Chang JH (2020) Clinical application of cryolipolysis in Asian patients for subcutaneous fat reduction and body contouring. Arch Plast Surg 47:62–69

Adjadj L, SidAhmed-Mezi M, Mondoloni M, Meningaud JP et al (2017) Assessment of the efficacy of cryolipolysis on saddlebags: a prospective study of 53 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 140:50–57

Mazzoni D, Lin MJ, Dubin DP, Khorasani H (2019) Review of non-invasive body contouring devices for fat reduction, skin tightening and muscle definition. Australas J Dermatol 60:278–283

Kwon TR, Yoo KH, Oh CT, Shin DH et al (2015) Improved methods for selective cryolipolysis results in subcutaneous fat layer reduction in a porcine model. Skin Res Technol 21:192–200

Manstein D, Laubach H, Watannabe K, Farinelli W et al (2008) Selective cryolysis: a novel method of non-invasive fat reduction. Las Surg Med 40:595–604

Pugliese D, Melfa F, Guarino E, Cascardi E, et al. Histopathological features of tissue alterations induced by cryolipolysis on human adipose tissue. Aesthet Surg J 2020 Feb 6 [Epub ahead of print]

Harrington JL, Capizzi PJ (2017) Cryolipolysis for nonsurgical reduction of fat in the lateral chest wall post-mastectomy. Aesthet Surg J 37:715–772

Putra IB, Jusuf NK, Dewi NK (2019) Utilisation of cryolipolysis among Asians: a review on efficacy and safety. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 7:1548–1554

Falster M, Schardong J, Santos DPD, Machado BC, et al. (2019) Effects of cryolipolysis on lower abdomen fat thickness of healthy women and patient satisfaction: a randomized controlled trial. Braz J Phys Ther. 2019 Jul 26 [Epub ahead of print]

Derrick CD, Shridharani SM, Broyles JM (2015) The safety and efficacy of cryolipolysis: a systematic review of available literature. Aesthetic Surg J 35:830–836

Garibyan L, Sipprell WH, Jalian HR, Sakamoto FH et al (2014) Three-dimensional volumetric quantification of fat loss following cryolipolysis. Lasers Surg Med 46:75–80

Ingargiola MJ, Motakef S, Chung MT, Vasconez HC et al (2015) Cryolipolysis for fat reduction and body contouring: safety and efficacy of current treatment paradigms. Plast Reconstr Surg 135:1581–1590

Gage AA, Caruana JA Jr, Montes M (1982) Critical temperature for skin necrosis in experimental cryosurgery. Cryobiology 19:273–282

Zelickson B, Egbert BM, Preciado J, Allison J (2009) Cryolipolysis for noninvasive fat cell destruction: initial results from a pig model. Dermatol Surg 35:1462–1470

Swanson E (2015) Cryolipolysis: The importance of scientific evaluation of a new technique. Aesthet Surg J 35:NP116–119

Pinto H, Arredondo E, Ricart-Jane D (2013) Evaluation of adipocytic changes after a simil-lipocryolysis stimulus. Cryo Lett 34:100–105

Kilmer SL (2017) Prototype CoolCup cryolipolysis applicator with over 40% reduced treatment time demonstrates equivalent safety and efficacy with greater patient preference. Lasers Surg Med 49:63–68

Rivers JK, Ulmer M, Vestvik B, Santos S (2018) A customized approach for arm fat reduction using cryolipolysis. Lasers Surg Med 50:732–737

Munavalli GS, Panchaprateep R (2015) Cryolipolysis for targeted fat reduction and improved appearance of the enlarged male breast. Dermatol Surg 41:1043–1051

Leal Silva H, Hernandez EC, Vasquez MG, Leal Delgado S et al (2017) Noninvasive submental fat reduction using colder cryolipolysis. J Cosmet Dermatol 16:460–465

Jalian HR, Avram MM (2013) Cryolipolysis: a historical perspective and current clinical practice. Semin Cutan Med Surg 32:31–34

Jain M, Savage NE, Spiteri K, Snell BJ (2020) A 3-dimensional quantitative analysis of volume loss following submental cryolipolysis. Aesthet Surg J 40:123–132

Boey GE, Wasilenchuk JL (2014) Enhanced clinical outcome with manual massage following cryolipolysis treatment: a 4-month study of safety and efficacy. Lasers Surg Med 46:20–26

Juhasz M, Leproux A, Durkin A, Tromberg B, et al. Use of a novel, noninvasive imaging system to characterize metabolic changes in subcutaneous adipose tissue after cryolipolysis. Dermatol Surg. Sep 23 2019[Epub ahead of print]

Zelickson BD, Burns AJ, Kilmer SL (2015) Cryolipolysis for safe and effective inner thigh fat reduction. Lasers Surg Med 47:120–127

de Almeida GOO, Antonio CR, de Oliveira GB, Rollemberg I et al (2015) Estudo epidemiológico de 740 áreas tratadas com criolipólise para gordura localizada. Surg Cosmet Dermatol 7:316–319

Sasaki GH, Abelev N, Tevez-Ortiz A (2014) Noninvasive selective cryolipolysis and reperfusion recovery for localized natural fat reduction and contouring. Aesthet Surg J 34:420–431

Dierickx CC, Mazer J-M, Sand M, Koenig S et al (2013) Safety, tolerance, and patient satisfaction with non-invasive cryolipolysis. Dermatol Surg 39:1209–1216

Swanson E (2015) Cryolipolysis: a question of scientific and photographic integrity. Plast Reconstr Surg 136:862e–864e

Carruthers J, Stevens WG, Carruthers A, Humphrey S (2014) Cryolipolysis and skin tightening. Dermatol Surg 40(Suppl 12):S184–189

Jones IT, Vanaman Wilson MJ, Guiha I, Wu DC et al (2018) A split-body study evaluating the efficacy of a conformable surface cryolipolysis applicator for the treatment of male pseudogynecomastia. Lasers Surg Med 50:608–612

Eldesoky MTM, Mohamed Abutaleb EEM, Mousa GSM (2016) Ultrasound cavitation versus cryolipolysis for non-invasive body contouring. Australas J Dermatol 57:288–293

de Gusmão PR, Canella C, de Gusmão BR, Filippo AA, et al (2020) Cryolipolysis for local fat reduction in adults from Brazil: A single-arm intervention study. J Cosmet Dermatol Apr 12 2020 [Epub ahead of print]

Nseir I, Lievain L, Benazech D, Carricaburu A, et al. (2018) Skin necrosis of the thigh after a cryolipolysis session: a case report. Aesthet Surg J 38:NP73-NP75

Choong WL, Wohlgemut HS, Hallam MJ (2017) Frostbite following cryolipolysis treatment in a beauty salon: a case study. J Wound Care 26:188–190

Oliveira PS, de Carvalho MA, Braga MA, Leite MMP, Medrado AP (2019) Comparative thermographic analysis at pre- and post-cryolipolysis treatment: clinical case report. J Cosmet Dermatol 18(1):136–141

Stevens WG (2014) Does cryolipolysis lead to skin tightening? A first report of cryodermadstringo. Aesthet Surg J 34:32–34

Swanson E (2019) In defense of evidence-based medicine in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 143:898e–899e

Al Deek NF (2018) Rethinking evidence-based medicine in plastic and reconstructive surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 142:429e

Raphael BA, Wasserman DI (2013) Getting to the bare bones: a comprehensive update of non-invasive treatments for body sculpting. Curr Dermatol Rep 2:144–149

Abdel-Aal NM, Elerian AE, Elmakaky AM, Alhamaky DMA (2020) Systemic effects of cryolipolysis in central obese women: a randomized controlled trial. Lasers Surg Med Apr 2020 [Epub ahead of print]

Friedmann DP (2019) Cryolipolysis for noninvasive contouring of the periumbilical abdomen with a nonvacuum conformable-surface applicator. Dermatol Surg 45:1185–1190

Suh DH, Park JH, Jung HK, Lee SJ et al (2018) Cryolipolysis for submental fat reduction in Asians. J Cosmet Laser Ther 20:24–27

Savacini MB, Bueno DT, Molina ACS, Lopes ACA, et al.(2018) Effectiveness and safety of contrast cryolipolysis for subcutaneous-fat reduction. Dermatol Res Pract 2018:5276528

Meyer PF, Furtado ACG, Morais SFT, de Arujo Neto LG et al (2017) Effects of cryolipolysis on abdominal adiposity of women. Cryo-Letters 38:379–386

Klein KB, Bachelor EP, Becker EV, Bowes LE (2017) Multiple same day cryolipolysis treatments for the reduction of subcutaneous fat are safe and do not affect serum lipid levels or liver function tests. Lasers Surg Med 49:640–644

Bernstein EF, Bloom JD (2017) Safety and efficacy of bilateral submental cryolipolysis with quantified 3-dimensional imaging of fat reduction and skin tightening. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 19:350–357

Carruthers JD, Humphrey S, Rivers JK (2017) Cryolipolysis for reduction of arm fat: safety and efficacy of a prototype CoolCup applicator with flat contour. Dermatol Surg 43:940–949

Lee SJ, Jang HW, Kim H, Suh DH et al (2016) Non-invasive cryolipolysis to reduce subcutaneous fat in the arms. J Cosmet Laser Ther 18:126–129

Stevens WG, Bachelor EP (2015) Cryolipolysis conformable-surface applicator for nonsurgical fat reduction in lateral thighs. Aesthet Surg J 35:66–71

Kim J, Kim DH, Ryu HJ (2014) Clinical effectiveness of non-invasive selective cryolipolysis. J Cosmet Laser Ther 16:209–213

Shek SY, Chan NPY, Chan HH (2012) Non-invasive cryolipolysis for body contouring in Chinese-a first commercial experience. Lasers Surg Med 44:125–130

Klein KB, Zelickson B, Riopelle JG, Okamoto E et al (2009) Non-invasive cryolipolysisTM for subcutaneous fat reduction does not affect serum lipid levels or liver function tests. Lasers Surg Med 41:785–790

Wanitphakdeedecha R, Sathaworawong A, Manuskiatti W (2015) The efficacy of cryolipolysis treatment on arms and inner thighs. Lasers Med Sc 30:2165–2169

Rodopoulou S, Gavala MI, Keramidas E (2020) Three-dimensional cryolipolysis for submental and lateral neck fat reduction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 8:e2789

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

For this type of study, informed consent is not required.For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Atiyeh, B.S., Fadul, R. & Chahine, F. Cryolipolysis (CLL) for Reduction of Localized Subcutaneous Fat: Review of the Literature and an Evidence-Based Analysis. Aesth Plast Surg 44, 2163–2172 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-020-01869-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-020-01869-x