Abstract

Purpose

The objective of the study was to compare the functional outcomes and the complication rate of the patients with C. acnes contamination at the end of the primary reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) surgery to those patients without C. acnes contamination.

Method

A total of 162 patients were included. In all cases, skin and deep tissue cultures were obtained. A molecular typing characterization of the C. acnes strains was performed. Functional outcomes were assessed with the Constant score at the two and five year follow-up and all complications were also recorded.

Results

A total of 1380 cultures were obtained from the 162 primary RSA surgeries. Of those, 96 turned out to be positive for C. acnes. There were 25 patients with positive cultures for C. acnes. The overall postoperative Constant score was not significantly different between those patients having C. acnes–positive cultures and those with negative cultures at the two and five year follow-up (59.2 vs. 59.6 at two years, p 0.870, and 59.5 vs. 62.4 at five years, p 0.360). Patients with positive cultures presented a higher complication rate (p 0.001) with two infections, one revision surgery, and one dislocation.

Conclusion

Patients ending up with C. acnes–positive cultures after primary shoulder arthroplasty surgery do not have worse clinical outcomes when compared to patients having negative cultures, but a greater number of complications were found in those patients with C. acnes–positive cultures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The presence of Cutibacterium acnes at the end of many primary shoulder surgeries has been extensively documented. Depending on the population studied, the surgery performed, and the number of cultures obtained, the C. acnes–positive culture rate can range from 9.3 to 41.8% [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Apparent aseptic revision shoulder arthroplasty cases constitute another source of positive cultures, mostly due to C. acnes detection [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. The burden of the presence of C. acnes at the end of the primary surgery can be quite varied, with some patients having many positive cultures while others present with just one positive culture. Moreover, the positivity rate, the delay in detecting it, makes it even more difficult to interpret the meaning of these positive cultures [10, 12, 22, 25,26,27]. Indeed, there is still a gray zone and a debate when trying to exactly define the difference between C. acnes contamination and true infection relative to the different parameters suggested.

Consequently, the clinical meaning of these positive cultures at day seven, day ten or day 12 is still unclear. However, it remains a cause of concern since it has been recently reported that the C. acnes clinical strain present at the end of primary shoulder arthroplasties can be the cause of a future C. acnes periprosthetic joint infection a few months or a year later [28]. There is also evidence that the C. acnes subtypes most involved in periprosthetic shoulder joint infections are commonly found as contaminants in deep tissues at the end of the primary surgery [29]. Many times, commonly used lab tests to rule out infection like the C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate remain negative in torpid C. acnes infections. There can also be a lack of the common clinical signs of infection such as fever, erythema or swelling [1, 24]. Quite often, pain and stiffness are the only clinical signs present to suspect a C. acnes infection [30].

In this context, there is little information if the patients that end up with C. acnes contamination after the primary arthroplasty surgery have different functional outcomes or complication rates when compared to those without C. acnes contamination [31].

The objective of the present study was to compare the functional outcomes and the complication rates of the patients with C. acnes contamination at the end of the primary shoulder arthroplasty surgery to those without C. acnes contamination.

Materials and methods

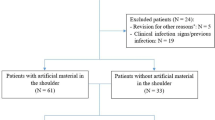

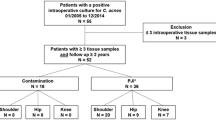

It is a retrospective study, with the data obtained prospectively, including primary reverse shoulder arthroplasties (RSA) performed by a single shoulder surgeon in a tertiary center. In all cases, a Delta Xtend (DePuy, Warsaw, IN) was implanted. This is a series of consecutive cases of patients that had undergone primary surgery with an RSA from September 2013 to December 2016 because of a rotator cuff–deficient shoulder, an acute fracture or a fracture sequela. The exclusion criteria included an active infection, an invasive shoulder treatment in the six months prior to surgery, an Arthro-SCAN or Arthro-MRI in the last 6 months before surgery, previous shoulder surgeries, and revision cases. One hundred sixty-seven patients met the inclusion criteria. Five patients were excluded because of incomplete sample collection, leaving 162 patients. In the first 67 cases, five cultures were obtained. In the remaining 95 cases, 11 cultures were obtained because of the design of a study that was published elsewhere reporting the number of positive cultures. The cultures were marked to identify their origin in the following manner. When 11 cultures were obtained, numbers one and two belonged to skin, number three belonged to subcutaneous tissue, numbers four and five to the bursa over the greater tuberosity, numbers six through nine to the area around the long head of the biceps insertion, and numbers ten and 11 again to the bursa over the greater tuberosity. When five cultures were obtained, the first two belonged to skin, and the last three to deep tissues. Skin cultures were obtained just after skin incision and included dermal and subdermal tissue. In all the cases, every culture was obtained after opening a set of sterile instruments. All the cultures were obtained after skin preparation with the “Bactiseptic®” solution (Vesismin Chemicals, Barcelona, Spain) composed of 2% chlorhexidine gluconate and 70% isopropylic alcohol. It was also after standard antibiotic prophylaxis, consisting in cefazolin 2 g endovenous (ev) 30 to 60 min before incision, when it was administrated. Patients were functionally assessed at the two and five year follow-up. The functional outcomes of the patients included were obtained with the aid of the Constant score by an independent examiner blinded to the results of the cultures at the two and five year follow-up [32]. Any complication at any point in the follow-up was also prospectively recorded (dislocation, infection, loosening of the components). Periprosthetic joint infections were also recorded following the International Consensus on Musculoskeletal Infection (ICM) with the break down into definite, probable, possible, and unlikely [33].

Age, gender, diagnosis, laterality, BMI, ASA, approach, glenosphere size, cementation of the implant, comorbidities, and the medications taken by the patients were also recorded.

Microbiology culture

Each tissue sample was individually homogenized with a mortar and pestle and was inoculated on a PolyVitex agar plate (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France), a Schaedler agar plate (bioMérieux), and in thioglycolate broth (BBL™ Becton Dickinson, Le Pont de Claix, France). These cultures were incubated at 37 °C aerobically (with 5% CO2) for seven days and anaerobically for 14 days. A culture was considered positive for C. acnes when two or more colonies were observed. Bacterial identification was performed by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) spectrometry (Brucker, Germany).

Molecular typing characterization of the C. acnes strains was performed following the protocol previously described [16, 28].

Statistics

For descriptive statistics, quantitative variables were described as mean and standard deviations. Qualitative variables were described with frequency tables (number and percentage).

Between group comparisons were performed for negative vs. positive cultures and from those positives. The statistical tests used for these comparisons were the chi-square or Fisher exact, as appropriate, for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U for continuous variables. The choice of this non-parametric option was because the violation of normality assumption in a significant number of continuous variables.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 15.1. Results were considered statistically significant at p value < 0.05.

All the included patients signed informed consent to participate in this study. The study was approved by the ethical committee with number 2014/5996/I (CEIC-Parc de Salut Mar).

Results

This study included 136 females (84%) and 26 males (16%) with a mean age of 74 years (55–89). The indication for surgery was a rotator cuff–deficient shoulder in 123 cases (75.9%), an acute fracture in 22 cases (13.6%), and a fracture sequela in 17 cases (10.5%).

A total of 1380 cultures were obtained from the 162 primary RSA surgeries, and 96 of them turned to be positive for C. acnes (7.0%) for the deep tissues. Out of the 162, there were 25 patients with positive cultures. Thirteen of them were male and 12 were female. Males had an overall rate of positivity rate of 50% while it was 8.8% in the females (p < 0.001). Among the patients with positive cultures for C. acnes, eight belonged to subtype IA (33.3%), four to IB (16.7%), three to II (12.5%), four to IA and IB (16.7%), and two to II and IB (8.3%). Unfortunately, subtyping of the C. acnes isolated was not done in four patients.

The age was significantly higher in the non-positive group (75.4 vs. 71.7, p = 0.008). The ASA score was significantly higher in the positive group (p = 0.007). Overall, patients with positive cultures had a marginally significantly higher number of comorbidities. Antidepressant medication intake was more commonly detected in patients with negative C. acnes cultures, but that was because of the prevalence of this intake in females (Table 1).

The overall preoperative Constant score was not significantly different between those patients having C. acnes–positive cultures and those with negative cultures. However, there was a significant non-clinically relevant difference in pain. At the two year follow-up, the Constant score was not significantly different between those patients having C. acnes–positive cultures and those with negative cultures. Again, there was a significant non-clinically relevant difference in internal rotation. At the five year follow-up, the Constant score was not significantly different between those patients having C. acnes–positive cultures and those with negative cultures. Here, there was a significant non-clinically relevant difference in lateral rotation (Table 2).

No significant difference was noted at final follow-up relative to scapular notch development between the two groups. However, there were two C. acnes infections in the positive culture group. Both belonged to subtype II, clonal complex 53 and the K and SLST-type. According to the ICM criteria, in the C. acnes culture–positive group, there were 2 definite infections (8%), zero probable infection (0%), 11 possible infections (44%), and 12 unlikely infections (48%). According to the ICM criteria, in the C. acnes culture–negative group, there were zero definite infection (0%), zero probable infection (0%), zero possible infection (0%), and 137 unlikely infections (100%). None of the 11 possible infections in the C. acnes culture–positive group turned to definite infection during the five year follow-up period. Definite infection was determined following ICM criteria in two patients of the C. acnes culture–positive group, because of the presence of more than two C. acnes–positive cultures with phenotypically identical C. acnes at the revision surgery in both. In one of them also because of the presence of a sinus track, both patients presented pain and stiffness as well. [33] They required a two-stage exchange of the components. In the C. acnes culture–positive group, a third patient needed revision surgery because of unexplained pain, and the fourth one needed revision because of dislocation. One patient in the non-positive C. acnes group presented with aseptic loosening. Revision surgery was proposed but the patient chose not to proceed with further surgery. Any infection was recorded in the non-positive C. acnes group, not by C. acnes and any other different bacteria such as coagulase negative or others. The overall complication rate was significantly higher for the C. acnes–positive culture group (Table 3).

There were 12 patients with one positive culture for C. acnes, two with two positive cultures, three with three positive cultures, four with four positive cultures, two with five positive cultures, one with six positive cultures, and one with eight positive cultures. No correlation could be found between the number of positive cultures and the outcomes as measured with the Constant score or with the complication rate (Table 4).

Discussion

Patients that end up having C. acnes–positive cultures after primary reverse shoulder arthroplasty surgery do not differ in terms of clinical outcomes when compared to those patients that do not have positive cultures after the surgery. However, an increased number of complications were encountered in those patients when C. acnes contamination was found at the end of their primary surgery (16% vs. 0.8%).

The clinical meaning of C. acnes–positive cultures found at the end of primary shoulder prosthetic surgeries remains unclear. The prevalence of these positive cultures differs depending on many factors like the gender ratio (having males higher prevalence ratio), the age of the patients, the number of cultures obtained, the method of obtaining the cultures, and the number of colonies needed to declare a C. acnes–positive culture [4,5,6, 10, 17, 22, 26, 30, 34]. Currently, it is not completely clear what should be called C. acnes contamination and what should be called infection. Indeed, some authors feel that too much attention has been paid to the presence of C. acnes while others feel that C. acnes detection at the end of the primary surgery is a source of concern. Nevertheless, there is a recent publication showing that the C. acnes clinical strain detected at the end of primary surgeries can be responsible for periprosthetic joint infections [28].

The commonly used antibiotic prophylaxis (intravenous Cefazolin 2 g) and the standard skin preparation (2% chlorhexidine gluconate and 70% isopropyl alcohol) fail to completely eradicate C. acnes from skin surfaces and most likely from deep tissues, and different C. acnes phylotypes living in the sebaceous glands can be present at the end of primary shoulder surgery at different rates depending on the type of surgery, the gender and age of the patients included, the number of the cultures taken, and the definition of culture positivity [1, 6, 14, 16]. In the present study, the rate of colonization of primary reverse shoulder arthroplasty has been found to be of 15.4%. This rate may reflect the characteristics of the sample, mostly composed of elderly females.

Patients suffering a shoulder prosthetic infection caused by C. acnes usually do not show skin reactions such as swelling, erythema or sinus tract. Blood tests such as C-reactive protein (CRP), or the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and other biomarkers available can also be normal [1, 24]. Pain and stiffness can be the only symptoms present in chronic C. acnes infections [30]. In the present study, patients having contamination with C. acnes found at the end of primary surgery with a reverse shoulder prosthesis do not have more pain at midterm follow-up when compared with patients having negative cultures. Patients with positive cultures have a significant but non-clinically relevant pain difference before surgery (6.2 vs. 4.9 in a 15-point scale). Nevertheless, both groups significantly improve pain without significant differences between them at the two and five year follow-up (13 vs. 12.7 points at the 2-year follow-up and 13.4 and 12.7 at the five year follow-up).

Patients with positive cultures for C. acnes do not have worst outcomes when compared to patients with negative cultures in forward elevation or in abduction. At the two year follow-up, a significant but clinically non-relevant difference could be found with reference to internal rotation (3.1 vs. 4.8 in a 10-point scale). At the five year follow-up, a significant but clinically non-relevant difference could be found regarding external rotation (5.0 vs. 6.0 on a 10-point scale). Patients having positive cultures for C. acnes do not seem to present with any more stiffness at the midterm follow-up when compared to those having negative cultures. However, and because of the small number of patients having positive C. acnes, the study is not powerful enough to give a strong conclusion on that.

Patients that have C. acnes–positive cultures found at the end of primary reverse shoulder arthroplasty do not have more pain or stiffness than patients having negative cultures. However, they do have a significantly higher rate of complications. In the present study, two patients with positive C. acnes cultures developed an infection that required a two-stage exchange of the components. Another patient with positive cultures required revision surgery because of unexplained pain, and a fourth patient presented a dislocation of the reverse shoulder arthroplasty that required an open reduction and an exchange of the components. In the culture negative group, only one patient developed aseptic loosening of the glenoid component and went on to refuse a component exchange. Interestingly, the number of positive cultures for C. acnes does not correlate with the outcomes or with the complications rate, meaning that patients having many positive cultures do not do worse than those having only one positive culture. Zmistowski et al., in a recent publication, also failed to find significant differences in clinical outcomes when comparing patients with positive cultures vs. those without positive cultures. Moreover, they also did not find significant differences in the complication rate between the two cohorts [31].

Comorbidities seem to correlate with C. acnes contamination. Consequently, patients with positive cultures have significantly higher ASA score values. However, the BMI, diagnosis, laterality, glenosphere size, approach, and use of cement to fix the humeral component do not seem to correlate with C. acnes contamination.

Although the clinical meaning of the presence of C. acnes contamination at the end of primary shoulder arthroplasty surgery is not clear, it represents a cause of concern since the number of complications at the midterm follow-up of the patients having positive cultures seems to be higher than in patients with negative cultures. The fact that skin preparation and antibiotic prophylaxis are suboptimal in eradicating C. acnes from skin might push us to search for better alternatives [1, 6, 11, 14]. Recent studies have shown the efficacy of the topical application of benzoyl peroxide in reducing the burden of the C. acnes in skin. However, we still do not know whether this reduction will result in a reduction in the number of infections or complications [8, 35,36,37].

Among the strengths of the study is the uniformity of the methods of obtaining the cultures, the homogeneity of the patients included (primary reverse shoulder prostheses), and the length of the follow-up. As for the weaknesses, there is the retrospective nature of the study and the fact that only 25 patients turned out to be positive for C. acnes even though 162 patients were included. The purpose of the study was to know the influence of C. acnes in primary reverse shoulder arthroplasty, and that is the reason why females are much more predominant in the population included. The higher number of complications found in the C. acnes–positive group could be influenced by the fact that males were more predominant in the C. acnes–positive group, being gender a confounder; however, and because of the small number of complications, a multivariate analysis could not be done. Although the follow-up was 5 years, some complications, including infection, can show up after a longer follow-up period.

In conclusion, patients ending primary shoulder arthroplasty surgery with positive cultures for C. acnes do not have worse clinical outcomes when compared to patients with negative cultures. However, a greater number of complications were found in those patients having C. acnes–positive cultures.

References

Dodson CC, Craig EV, Cordasco FA et al (2010) Propionibacterium acnes infection after shoulder arthroplasty: a diagnostic challenge. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 19:303–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2009.07.065

Falconer TM, Baba M, Kruse LM et al (2016) Contamination of the surgical field with Propionibacterium acnes in primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 98:1722–1728. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.15.01133

Hsu JE, Matsen FA III, Whitson AJ, Bumgarner RE (2020) Cutibacterium subtype distribution on the skin of primary and revision shoulder arthroplasty patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 29:2051–2055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2020.02.0027

Hudek R, Brobeil A, Brüggemann H, Sommer F, Gattenlöhner S, Gohlke F (2021) Cutibacterium acnes is an intracellular and intra-articular commensal of the human shoulder joint. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 30:16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2020.04.020

Hudek R, Sommer F, Kerwat M, Abdelkawi AF, Loos F, Gohlke K (2014) Propionibacterium acnes in shoulder surgery: true infection, contamination, or commensal of deep tissue? J Shoulder Elbow Surg 23:1763–1771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2014.05.024

Kajita Y, Iwahori Y, Harada Y, Takahashi R, Deie M (2021) Incidence of Cutibacterium acnes in open shoulder surgery. Nagoya J Med Sci 83:151–157. https://doi.org/10.18999/nagjms.83.1.151

Koh CK, Marsh JP, Drinkovic D, Walker CG, Poon PC (2016) Propionibacterium acnes in primary shoulder arthroplasty: rates of colonization, patient risk factors, and efficacy of perioperative prophylaxis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 25:846–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2015.09.033

Kolakowski L, Lai JK, Duvall GT et al (2018) Benzoyl peroxide effectively decreases preoperative Cutibacterium acnes shoulder burden: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 27:1539–1544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2018.06.012

Levy O, Iyer S, Atoun E et al (2013) Propionibacterium acnes: an underestimated etiology in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis? J Shoulder Elbow Surg 22:505–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2012.07.007

Maccioni CB, Woodbridge AB, Balestro JCY et al (2015) Low rate of Propionibacterium acnes in arthritic shoulders undergoing primary total shoulder replacement surgery using a strict specimen collection technique. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 24:1206–1211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2014.12.026

Matsen FA III, Butler-Wu S, Carofino BC, Jette JL, Bertelsen A, Bumgarner R (2013) Origin of Propionibacterium in surgical wounds and evidence-based approach for culturing Propionibacterium from surgical sites. J Bone Joint Surg Am 95:e181(1-7). https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.L.01733

Matsen FA 3rd, Russ SM, Bertelsen A, Butler-Wu S, Pottinger PS (2015) Propionibacterium can be isolated from deep cultures obtained at primary arthroplasty despite intravenous antimicrobial prophylaxis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 24:844–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2014.10.016

Mook WR, Klement MR, Green CL, Hazen KC, Garrigues GE (2015) The incidence of Propionibacterium acnes in open shoulder surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 97:957–963. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.N.00784

Patel A, Calfee RP, Plante M, Fischer SA, Green A (2009) Propionibacterium acnes colonization of the human shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 18:897–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2009.01.023

Phadnis J, Gordon D, Krishnan J, Bain GI (2016) Frequent isolation of Propionibacterium acnes from the shoulder dermis despite skin preparation and prophylactic antibiotics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 25:304–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2015.08.002

Torrens C, Marí R, Alier A, Puig L, Santana F, Corvec S (2019) Cutibacterium acnes in primary reverse shoulder arthroplasty: from skin to deep layers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 28:839–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2018.10.016

Wong JC, Schoch BS, Lee BK et al (2018) Culture positivity in primary total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 27:1422–1428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2018.05.024

Ahsan ZS, Somerson JS, Matsen FA III (2017) Characterizing the Propionibacterium load in revision shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 99:150–154. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.16.00422

Falstie-Jensen T, Lange J, Daugaard H, Sorensen AKB, Ovesen J, Soballe K (2021) Unexpected positive cultures after revision shoulder arthroplasty: does it affect outcome? J Shoulder Elbow Surg 30:1299–1308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2020.12.0164

Foruria AM, Fox TJ, Sperling JW, Cofield RH (2013) Clinical meaning of unexpected positive cultures (UPC) in revision shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 22:620–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2012.07.017

McGoldrick E, McElvany MD, Butler-Wu S, Pottinger PS, Matsen FA III (2015) Substantial cultures of Propionibacterium can be found in apparently aseptic shoulders revised three years or more after index arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 24:31–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2014.05.008

Padegimas EM, Lawrence C, Narzikul AC et al (2017) Future surgery after revision shoulder arthroplasty: the impact of unexpected positive cultures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 26:975–981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2016.10.0123

Pottinger P, Butler-Wu S, Neradilek MB et al (2012) Prognostic factors for bacterial cultures positive for Propionibacterium acnes and other organisms in a large series of revision shoulder arthroplasties performed for stiffness, pain, or loosening. J Bone Joint Surg Am 94:2075–2083. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.K.00861

Topolski MS, Chin PYK, Sperling JW (2006) Cofield RH (2006) Revision shoulder arthroplasty with positive intraoperative cultures: the value of preoperative studies and intraoperative histology. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 15:402–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2005.10.001

Achermann Y, Goldstein EJC, Coenye T, Shirtliff ME (2014) Propionibacterium acnes: from commensal to opportunistic biofilm-associated implant pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 27:419–440. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00092-13

Dagnelie MA, Khammari A, Dréno B, Corvec S (2018) Cutibacterium acnes molecular typing: time to standardize the method. Clin Microbiol Infect 24:114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2018.03.010

Stull JD, Nicholson TA, Davis DE, Namdari S (2020) Addition of 3% hydrogen peroxide to standard skin preparation reduces Cutibacterium acnes-positive culture rate in shoulder surgery: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 29:212–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2019.09.038

Torrens C, Bellosillo B, Gibert J et al (2022) Are Cutibacterium acnes present at the end of primary shoulder prosthetic surgeries responsible for infection? Prospective study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 41:169–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-021-04348-6

Aubin GG, Lavigne JP, Foucher Y et al (2017) Tropism and virulence of Cutibacterium (formerly Propionibacterium) acnes involved in implant-associated infection. Anaerobe 47:73–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.04.009

Millett PJ, Yen YM, Price CS, Horan MP, van der Meijden OA, Elser F (2011) Propionobacter acnes infection as an occult cause of postoperative shoulder pain. Clin Orthop Relat Res 469:2824–2830. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-011-1767-4

Zmistowski B, Nicholson TA, Wang WL, Abboud JA, Namdari S (2021) What is the clinical impact of positive cultures at the time of primary total shoulder arthroplasty? J Shoulder Elbow Surg 30:1324–1328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2020.08.032

Constant CR, Murley AH (1987) A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res 214:160–164

Garrigues GE, Zmistowski B, Cooper AM, Green A, ICM Shoulder Group (2019) Proceedings from the 2018 International Consensus Meeting on Orthopedic Infections: the definition of periprosthetic shoulder infection. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 28:S8–S12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2019.04.034

Van Diek FM, Pruijn N, Spijkers KM, Mulder B, Kosse NM, Dorrestijn O (2020) The presence of Cutibacterium acnes on the skin of the shoulder after the use of benzoyl peroxide: a placebo-controlled, double-blinded, randomized trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 29:768–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2019.11.027

Chalmers PN, Beck L, Stertz I, Tashjian RZ (2019) Hydrogen peroxide skin preparation reduces Cutibacterium acnes in shoulder arthroplasty: a prospective, blinded, controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 28:1554–1561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2019.03.038

SaltzmanMD NGW, Gryzlo SM, Marecek GS, Koh JL (2009) Efficacy of surgical preparation solutions in shoulder surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91:1949–1953. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.H.00768

Scheer VM, Jungeström MB, Lerm M, Serrander L, Kalén A (2018) Topical benzoyl peroxide application on the shoulder reduces Propionibacterium acnes: a randomized study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 27:957–961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2018.02.038

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Xavier Duran Jordà, MStat, PhD (Methodology and Biostatistics Support Unit, Institute Hospital del Mar for Medical Research (IMIM), Barcelona, Spain) for his work in data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Carlos Torrens, Raquel Marí, Lluís Puig-Verdier, Fernando Santana, Albert Alier, Eva García-Jarabo, Alba Gómez-Sánchez, and Stèphane Corvec. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Carlos Torrens and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the ethical committee with number 2014/5996/I (CEIC-Parc de Salut Mar).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Torrens, C., Marí, R., Puig-Verdier, L. et al. Functional outcomes and complications of patients contaminated with Cutibacterium acnes during primary reverse shoulder arthroplasty: study at two- and five-years of follow-up. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 47, 2827–2833 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-023-05971-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-023-05971-y