Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the results of arthroscopic cuff reconstruction, which is currently preferred in our service, and to compare functional outcome after arthroscopic cuff reconstruction comparing different types and sizes of rotator cuff tears. We switched completely from open repair to the full-arthroscopic repair > ten years ago, and since then, we are developing a technique that can produce the best results. Therefore, we decided to verify results.

Methods

Seventy-two patients with rotator cuff tear underwent arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Single-row arthroscopic repair using double-loaded metal anchors and margin-convergence sutures with concomitant procedures were performed in all cases. All patients were assessed and classified before and after surgery using the Constant scoring system and the Oxford Shoulder Score. Tears were measured and classified as medium (1–3 cm), large(3–5 cm) and massive (>5 cm).

Results

The average age of participants was 59 ± 9 years (33–76). There were five medium, 43 large and 23 massive tears. The average functional Constant score at the last follow-up was 91.68 ± 10.62, and the Oxford score averaged 43.23 ± 5.84 without statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) among groups Best results were in the massive-tear group, with an overall Constant score of 98.60 ± 2.61 and an average Oxford score of 47.60 ± 0.55. Full recovery was obtained between six months and one year. We used our own modified rehabilitation protocol and found no postoperative stiffness in this series.

Conclusions

Single-row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using double-loaded metal anchors and margin-convergence sutures with concomitant procedures, when necessary, provides excellent results. Pain, range of motion, muscle strength and function were significantly improved after single-row repair among all morphological types of cuff lesions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rotator cuff tear (RCT) is a major pathology in orthopaedic practice, affecting both athletes and the general (particularly the aging) population. Pain and functional diminution are the most frequent symptoms of rotator cuff impairment. The majority of RCT result from chronic overhead movements of the upper arm, lifting heavy objects or performing rapid hand movements [1–4]. Some activities, such as house painting, construction work or throwing (e.g. handball, water polo, tennis or baseball) require recurrent overhead movements, resulting in repeated and chronic tendon injuries. RCT impare everyday activities, cause sleep disturbances, pain and discomfort. Neglected tears lead to long-term consequences, such as progression of glenohumeral joint arthritis with or without narrowing of the subacromial space, resulting in a rotator cuff arthropathy [4, 5]. Small tears can be asymptomatic, but massive tears are constantly associated with loss of strength in abduction and external rotation. Certain pathologies of the long head of the biceps tendon (LB) cause constant shoulder pain and consequently decreased range of motion (ROM) in patients with massive RCT [6]. Available data favours the fact that the prevalence of RCT is increased in the senior population and that the aging is the most important factor in its pathology. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies show that 54% of adults >60 have a RCT, while 4% of those <40 are asymptomatic [7].

Anatomic diagnosis is prerequisite for determining adequate treatment. Treatment approach comprises assessing ROM, muscle function and strength using various clinical tests and performing plain radiologic examination followed by ultrasound (US) and/or MRI. During surgery, arthroscopic inspection provides precise evaluation of the lesions and adequate assessment of coexisting pathologies, such as labral tears, lesions of the LB and capsular, ligamental or specific muscular lesions such as some subscapularis lesions [8]. Earlier operative repair may result in better patient outcomes and decreased medical costs.

The most significant criteria in determining adequate treatment are persistent pain, grade of functional impairment (loss of physiological ROM and decreased strength) and patient-related parameters such as age, time elapsed from injury, expectations and events related to anaesthesia. Many studies have evaluated the results of nonoperative treatment for RCT. Gerber et al. [1] concluded that nonoperative treatment is successful in patients with less physical demands and expectations, predominantly seniors, but progression of glenohumeral joint osteoarthritis is proven in such circumstances.

The objective of our study was to evaluate results of arthroscopic cuff reconstruction using the method currently preferred in our service after switching completely from open to arthroscopic repair.

Materials and methods

Participants and study design

Study participants were operated arthroscopically between 2000 and 2010. The study comprised 72 patients who agreed to participate and who were fully evaluated. The participants were divided into three groups according to tear size: medium, 1–3 cm; large, 3–5 cm; massive, >5 cm. The diagnosis was additionally confirmed with X-ray, US and MR imaging. RCT size was classified according to Cofield [9]. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Orthopedics, University of Zagreb, according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients had initially undergone unsuccessful conservative treatment, showing persistent moderate or severe pain at rest that would aggravate during active movement, consequently leading to loss of shoulder function. The surgical indication was in agreement with patient demand based on symptom severity, tear size, acromiohumeral index, impingement signs and functional limitations as evaluated by clinical scores. The main diagnosis was supraspinatus tear. Other coexistent rotator cuff pathologies were treated depending on intraoperative findings. Patients with large and massive tears were treated with a single-row (SR) repair. Five medium tears were treated with debridement only. All patients were independently assessed postoperatively using the Constant scoring system [10] and Oxford Shoulder Score at a minimum of six months and maximum of 111 months.

Surgical technique

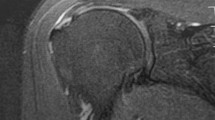

All shoulder surgeries were performed under US-guided interscalenic nerve block and/or general anaesthesia performed by the senior author (MM) with the patient in beach-chair position. The most important issues in addressing the RCT were type, size and concomitant pathologies (biceps avulsions or instability, subscapularis tears, etc.) that have been treated using the same procedure. After fulfilling our criteria, the attachment site was decorticated to the level of the so-called, cortical bleeding surface. Reconstruction was performed combining side-to-side reconstruction, finishing with a SR fixation technique with one stitch posted medially and one laterally in order to widen the surface of the tendon that should be compressed to the footprint (Figs. 1 and 2). The Corkscrew® titanium anchors (size 5.5 mm x 16.3 mm; Arthrex®) were used in all procedures. This anchor is caracterised by its small core diameter and large cancelous threads aimed at increasing the pull-out strength; it has two eyelets and is double loaded with two FiberVire sutures.

Acromioplasty was performed in cases in which the subacromial space showed inflammation or bursitis in the area of contact between tendon and acromial undersurface. Postoperatively, patients had a 15° abduction sling and a personalised physical therapy protocol. They underwent rehabilitation until they achieved full ROM and maximised strength in the affected shoulder. Progress was checked regularly on a monthly basis.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (v17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test normality of distribution before further analysis. Differences between groups were determined using the Kruskal–Wallis test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When a statistically significant value was achieved, appropriate Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to determine the difference between averages. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Among 72 patients who completed the research, there were 31 men and 41 women. The average age was 58 ± 9 years (33–76); 54 were right shoulders and 18 left. There were five medium, 43 large and 23 massive tears. Maximum follow-up was 111 months, with a minimum of 47 months. Results and lengths of follow-up are displayed in 1. Arthroscopic examination showed lesions of the LB in 37 cases and subacromial bursitis in 39.

Kolmogorov–Smirnov test showed distribution and outliners in all variables. The majority of patients achieved good to excellent results postoperatively according to Constant and Oxford scores, without statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) among groups (Table 1). The most significant results were the increase in mobility and pain relief (Tables 2 and 3). Full recovery period after surgery ranged from six months to one year. There was no postoperative stiffness noted. All basic descriptive parameters per group are expressed as arithmetic mean ± standard deviation (SD). Patients with massive tears (n = 23) achieved an average total score of 94.30 ± 8,.5), while patients with large tears (n = 44) achieved 89.80 ± 11.69. Patients with massive tears had an evidently better Constant score (98.60 ± 2.61), while patients with medium and large tears had very similar results (89.00 ± 10.28 and 90.29 ± 10.40, respectively). Total Constant score for all patients operated was 91 ± 10 (Table 1). Oxford score for massive tears were 47 ± 0.5, medium tears 42 ± 5, and large tears 42 ± 5. Total Oxford score for all patients was 43 ± 5 (Table 1). Excellent clinical results and patient satisfaction were demonstrated in most cases (Figs. 3)

Discussion

This study shows that SR arthroscopic repair of RCT improves cuff integrity and functional outcomes in patients with medium, large and massive ruptures. Performing postoperative Constant score, we noticed a decrease in shoulder pain and an increase in ROM in affected shoulders. Full recovery period after surgery ranged between six months and one year. Pain, ROM, muscle strength and function all improved after SR arthroscopic repair and, surprisingly, scores were higher and outcomes better in patients with massive rupture; patients with medium and large tears had very similar results. Performing this study, we confirmed that arthroscopy repair is an equally successful method for medium, large and massive RCT. Our rehabilitation protocol showed equal results for all RCT sizes, and we found no re-tears as measured by postoperative scores. There was no postoperative stiffness noted in any patient, and age did not influence treatment method.

Rotator cuff surgery aims to provide tendon fixation secure enough to hold the repaired tendon in place until biological healing occurs [11]. The most dominant surgical approaches for RCT repair are SR and double-row (DR) arthroscopic constructs. Results in different studies conducted to determine whether traditional DR or SR RCT repair provides superior clinical outcomes and structural healing are discordant. Burks et al. [12] investigates 40 patients randomised to SR or DR repair. At one year, patients had several clinical measures performed as well as repeat MRI. The authors found no significant difference between groups on either clinical or MRI evaluation. Francheschi et al. [13] conducted a randomised study of SR and DR repairs and found no difference in patient scores or MRI arthrograms at follow-up. There is some clinical evidence in other studies to support great functional differences between techniques, except for patients with large or massive RCT (≥3 cm) or resulting in a lower rate of re-tear using the DR method [14–18]. Numerous meta-analyses have been published, analysing hundreds or even thousands of clinical results to compare the two approaches. There is no doubt among researchers that DR produces a mechanically superior construct than SR in restoring the anatomical footprint of the rotator cuff, but these mechanical advantages do not translate into superior clinical performances or even with MRI findings. Also, it must be noted that DR requires longer surgical time, is more expensive, requires more suture anchors and may be technically more demanding [13]. Mascarenchas et al. [19] conducted a systematic review of meta-analyses comparing SR and DR RTC repair and found in six meta-analyses no differences between SR and DR for patient outcomes, whereas two studies favored DR for tears >3 cm. Two meta-analyses found no structural healing differences between SR and DR, three found DR Outcomes of our study show a significant short- to medium-term improvement in pain, function and patient satisfaction. We achivied good and excellent results independent of tear size. This is in agreement with Bukhart et al. [3], who achieved 95 % good to excellent result regardless tear size. Many articles show a high failure rate of cuff integrity after arthroscopic repair, particularly with large and massive tears. Galatz et al. [20] found that arthroscopic repair of large and massive cuff tears led to a very high percentage of recurrent defects, almost 94%. Bishop et al. [21] found that only 24% of arthroscopically repaired large cuff tears were intact on postoperative MRI evaluation and that large tears had twice the re-tear rate after arthroscopic repair. Our patients were not routinely imaged postoperatively. We have no reason to believe that our rate of cuff healing would be any higher than that reported in the literature. However, if we apply findings from Miller et al. [22], who concluded that “recurrent tear after arthroscopic repair of large RCT is more likely to occur late (> three months) in the postoperative period and will be associated with inferior clinical outcome scores”, we find that our rate of re-tear was indeed low. Nevertheless, our rate of clinically successful arthroscopic cuff repair reinforces the view that complete cuff healing is not necessary for successful cuff-repair surgery, and as Russell et al. described [23], the most important outcome is a high level of patient satisfaction.

This study evaluated the effects of arthroscopic SR repair of medium, large and massive RCT in different age groups. Surprisingly, functional outcome was much better among patients with massive tears in comparison with those with small and large tears, both in Constant–Murley and Oxford scores, although this was not statistically significant. Burkhart at al. [3] reported 98 % good or excellent results, regardless of tear size, with an improvement in ROM, functional outcome and pain relief. Kukkonen et al. [24] described that intra-operatively detected tear size correlates significantly with pre-operative Constant score (r = −0.20, p < 0.0001) but even more strongly and more significantly between tear size and final postoperative Constant score (r = −0.36, p < 0.0001); our study reported here does not support this assertion. In the same context, Holtby et al. [5] showed that reparability was associated with tear shape (p < 0.0001), size (p = 0.002),and tendon quality (p < 0.0001). Those results may also depend on mechanical quality of repair on or biological quality of the tendon fixed, which are difficult indications to evaluate. The failure rate after repair in other studies varies from 9 % to 29 %. [4, 1, 14] The fact that we found no failure, although our study population had the all described failure risks [24], could be explained by several factors: (a) different approach to the criterion failure compared with other studies; (b) relatively younger group of patients, with average age 59 ± nine years ; c) surgical technique and modified postoperative rehabilitation protocol. We firmly believe that our overall approach could be a good solution for large and massive RCT. Also, we found no shoulder stiffness in our operated patients in relation to significant postoperative complications. Stiffness is a dominant sign of concomitant adhesive capsulitis and re-tear.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that single-row (SR) arthroscopic rotator cuff reconstruction is a successful repair method in large and massive RCT resulting in pain relief and improved mobility, muscle strength and overall function. If followed by an adapted rehabilitation protocol, this technique gives notable patient satisfaction.

References

Gerber C, Wirth SH, Farshad M (2011) Treatment options for massive rotator cuff tears J. Shoulder Elbow Surg 20(2):20–29. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2010.11.028

Burkhart SS, Danaceau SM, Pearce CE Jr (2001) Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: analysis of results by tear size and by repair technique-margin convergence versus direct tendon-to-bone repair. Arthroscopy 17(9):905–912. doi:10.1053/jars.2001.26821

Burkhart SS (2001) Arthroscopic treatment of massive rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res 390(390):107–118. doi:10.1097/00003086-200109000-00013

Jones CK, Savoie FH (2003) Arthroscopic repair of large and massive rotator cuff tears. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg 19(6):564–571. doi:10.1016/S0749-8063(03)00169-5

Holtby R, Razmjou H (2014) Relationship between clinical and surgical findings and reparability of large and massive rotator cuff tears: a longitudinal study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15(1):180. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-180

Boileau P, Ahrens PM, Hatzidakis AM (2004) Entrapment of the long head of the biceps tendon: the hourglass biceps—a cause of pain and locking of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elb Surg 13(3):249–257. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.01.001

Bartolozzi A, Andreychik D, Ahmad S (1994) Determinants of outcome in the treatment of rotator cuff disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res 308(308):90–97

Yamaguchi K, Levine WN, Marra G, Galatz LM, Klepps S, Flatow EL (2003) Transitioning to arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: the pros and cons. Instr Course Lect 52(1):81–92, PMID: 12690842

Harryman DT, Sidles JA, Harris SL, Matsen FA (1992) Laxity of the normal glenohumeral joint: a quantitative in vivo assessment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1(2):66–76. doi:10.1016/S1058-2746(09)80123-7:

Constant CR, Murley AH (1987) A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res 214(214):160–164, PMID: 3791738

Lo IKY, Burkhart SS (2004) Arthroscopic repair of massive, contracted, immobile rotator cuff tears using single and double interval slides: technique and preliminary results. Arthroscopy 20(1):22–33. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2003.11.013

Burks RT, Crim J, Brown N, Fink B, Greis PE (2009) A prospective randomized clinical trial comparing arthroscopic single- and double-row rotator cuff repair: magnetic resonance imaging and early clinical evaluation. Am J Sports Med 37(4):674–682. doi:10.1177/0363546508328115

Franceschi F, Ruzzini L, Longo UG, Martina FM, Zobel BB, Maffulli N, Denaro V (2007) Equivalent clinical results of arthroscopic single-row and double-row suture anchor repair for rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 35(8):1254–1260. doi:10.1177/0363546507302218

Carbonel I, Martinez AA, Calvo A, Ripalda J, Herrera A (2012) Single-row versus double-row arthroscopic repair in the treatment of rotator cuff tears: a prospective randomized clinical study. Int Orthop 36(9):1877–1883. doi:10.1155/2013/914148

Tudisco C, Bisicchia S, Savarese E, Fiori R, Bartolucci DA, Masala S, Simonetti G (2013) Single-row vs. double-row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: clinical and 3 Tesla MR arthrography results. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 14(1):43. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-14-43

McCormick F, Gupta A, Bruce B, Harris J, Abrams G, Wilson H, Hussey K, Cole BJ (2014) Single-row, double-row, and transosseous equivalent techniques for isolated supraspinatus tendon tears with minimal atrophy: a retrospective comparative outcome and radiographic analysis at minimum 2-year followup. Int J Shoulder Surg 8(1):15–20. doi:10.4103/0973-6042.131850

Zhang Q, Ge H, Zhou J, Yuan C, Chen K, Cheng B (2013) Single-row or double-row fixation technique for full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 8(7):e68515

Saridakis P, Jones G (2010) Outcomes of single-row and double-row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92(3):732–742. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.01295

Mascarenhas R, Chalmers PN, Sayegh ET, Bhandari M, Verma NN, Cole BJ, Romeo AA (2014) Is double-row rotator cuff repair clinically superior to single-row rotator cuff repair: a systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Arthroscopy 30(9):1156–1165. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2014.03.015

Galatz LM, Ball CM, Teefey SA, Middleton WD, Yamaguchi K (2004) The outcome and repair integrity of completely arthroscopically repaired large and massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86-A(2):219–224, PMID: 14960664

Bishop J, Klepps S, Lo IK, Bird J, Gladstone JN, Flatow EL (2006) Cuff integrity after arthroscopic versus open rotator cuff repair: a prospective study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 15(3):290–299

Miller BS, Downie BK, Kohen RB, Kijek T, Lesniak B, Jacobson JA, Hughes RE, Carpenter JE (2011) When do rotator cuff repairs fail? serial ultrasound examination after arthroscopic repair of large and massive rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med 39(10):2064–2070. doi:10.1177/0363546511413372

Russell RD, Knight JR, Mulligan E, Khazzam MS (2014) Structural integrity after rotator cuff repair does not correlate with patient function and paina meta-analysis. J Bone Jt Surg 96(4):265–271. doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.00265

J. Kukkonen, T. Kauko, P. Virolainen, and V. Aärimaa (2013) The effect of tear size on the treatment outcome of operatively treated rotator cuff tears. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc.:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2647-0

Koo SS, Parsley BK, Burkhart SS, Schoolfield JD (2011) Reduction of postoperative stiffness after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: results of a customized physical therapy regimen based on risk factors for stiffness. Arthroscopy 27(2):155–160. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2010.07.007

Conflicts of interests

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miškulin, M., Vrgoč, G., Sporiš, G. et al. Single-row arthroscopic cuff repair with double-loaded anchors provides good shoulder function in long-term follow-up. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 39, 233–240 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-014-2557-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-014-2557-x