Abstract

Objective

To report the prevalence of MRI features commonly associated with posterior ankle impingement syndrome in elite ballet dancers and athletes and to compare findings between groups.

Materials and methods

Thirty-eight professional ballet dancers (47.4% women) were age- and sex-matched to 38 elite soccer or cricket fast bowler athletes. All participants were training, playing, and performing at full workload and underwent 3.0-T standardised magnetic resonance imaging of one ankle. De-identified images were assessed by one senior musculoskeletal radiologist for findings associated with posterior ankle impingement syndrome (os trigonum, Stieda process, posterior talocrural and subtalar joint effusion-synovitis, flexor hallucis longus tendon pathology and tenosynovitis, and posterior ankle bone marrow oedema). Imaging scoring reliability testing was performed.

Results

Posterior talocrural effusion-synovitis (90.8%) and subtalar joint effusion-synovitis (93.4%) were common in both groups, as well as the presence of either an os trigonum or Stieda process (61.8%). Athletes had a higher prevalence of either os trigonum or Stieda process than dancers (74%, 50% respectively, P = 0.03). Male athletes had a higher prevalence of either os trigonum or Stieda process than male dancers (90%, 50% respectively, P = 0.01), or female athletes (56%, P = 0.02). Posterior subtalar joint effusion-synovitis size was larger in dancers than athletes (P = 0.02). Male and female dancers had similar imaging findings. There was at least moderate interobserver and intraobserver agreement for most MRI findings.

Conclusion

Imaging features associated with posterior impingement were prevalent in all groups. The high prevalence of os trigonum or Stieda process in male athletes suggests that this is a typical finding in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Posterior ankle impingement syndrome (PAIS), characterised by posterior ankle pain in positions of ankle plantarflexion, has been reported in ballet dancers [1,2,3,4,5] and other athletic and non-athletic populations [6,7,8]. Posterior ankle impingement syndrome is an important cause of pain and injury in elite ballet and athletic populations [9, 10].

Atraumatic PAIS is due to cumulative microtrauma to the posterior ankle structures, especially in populations exposed to repetitive end-range ankle plantarflexion [2, 11], causing pain in plantarflexion when soft-tissue and osseous structures are compressed within the tibiocalcaneal interval [3, 12]. Osseous anomalies of the posterior talus, namely the os trigonum and Stieda process, are often implicated as causative structures in PAIS and are one of the most common targets of surgical intervention [5, 7]. Other imaging findings such as posterior ankle effusion-synovitis, bone marrow oedema, flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon pathology, and tenosynovitis have also been described in populations diagnosed with PAIS, including dancers, cricket players (fast bowlers), and soccer players [1, 2, 4, 13, 14]. Os trigonum and Stieda process prevalence in various populations have been reported between 2.3 to 32.5% and 14.7 to 36.5%, respectively [15,16,17,18,19]. The prevalence of these osseous anomalies appears to be higher in ballet dancers [1, 20] and soccer players presenting with PAIS [10] than in the general population.

The mechanism of injury in PAIS may vary between dancers and athletes. Environmental parameters such as floor surface and footwear differ substantially. Dancers are renowned for their extreme ankle plantarflexion range, which is regularly performed in full weight-bearing. Cricket fast bowlers use their front leg to brake [21], resulting in rapid deceleration of the front foot into positions of ankle plantarflexion. Dancers achieve greater ankle plantarflexion ranges than fast bowlers and soccer players [21,22,23,24]. The ankles of fast bowlers and soccer players may be exposed to higher peak ground reaction forces [25, 26] than those of ballet dancers [27, 28]. Furthermore, studies have described biomechanical variations between sexes within the same sport; for example, female fast bowlers achieve significantly greater ankle plantarflexion at final stride [21] and smaller peak ground reaction forces than their male counterparts [29]. In ballet, pointe shoes are worn almost exclusively by women. It is unknown whether these factors lead to distinct MRI features.

Atraumatic injuries such as PAIS have an insidious presentation and symptoms can be transient. It is common for elite dancers and athletes to continue training and competing/performing at full workloads despite pain of various origins, using minor adaptations (e.g. adjustments in choreography), treatment, or medications to control their symptoms [30,31,32]. It is also common for athletes/dancers to defer rest until a convenient time, such as the off-season or in between performance seasons. Consequently, some injuries may not result in time loss [30]. Imaging studies reporting os trigonum or Stieda process and other PAIS-associated imaging findings in dance and athletic populations have only investigated symptomatic or operative groups. Imaging findings have not been reported in these populations participating in their activity at full workloads, nor have comparisons been made between sports or sexes.

The aim of this study is to report the prevalence of MRI findings commonly associated with PAIS in a typical population of elite ballet dancers, soccer players, and cricket fast bowlers and to explore the differences between professions and sexes.

Materials and methods

Forty professional male and female ballet dancers (47.4% women) were age (± 2 years)- and sex-matched to 40 elite cricket fast bowlers (n = 25) or soccer players (n = 15). Participants were older than 18 years of age, trained in the activity (ballet, cricket, soccer) at least three times per week since age 10, and were training, playing, and performing at full workloads at time of testing. Exclusion was made if there was a history of severe foot or ankle trauma or surgery, systemic neurological or inflammatory conditions, any contraindications to MRI (metal implants, pregnancy, or claustrophobia), or corticosteroid injection to the foot or ankle in the 6 weeks prior to testing. Clinical testing and imaging were conducted between March 2017 and April 2019.

Participants underwent unilateral ankle MRI. In dancers and soccer players, the ankle scanned was either the symptomatic one or had the greater history of symptoms. If neither ankle had current or previous symptoms, imaging side was determined via coin toss. All cricket fast bowlers had the ankle of their front bowling foot imaged (if they were a right-arm bowler, their left ankle was scanned). Each participant provided information on the current level of function (normal, nearly normal, abnormal, or severely abnormal) in the ankle imaged, previous lateral ankle sprain, and age when they commenced training at least four times per week.

Eighty participants were recruited and scanned (40 dancers, 40 athletes). One female fast bowler had the incorrect ankle scanned; therefore, she and her matched dancer were withdrawn from the analysis. One male dancer’s images were unable to be located; therefore, he and his matched athlete were withdrawn from the analysis. The remaining 76 participants were included in the analysis. In the athlete group (n = 38), 24 were fast bowlers (16 male, 8 female) and 14 were soccer players (4 male, 10 female) (Table 1).

Imaging was performed across two locations according to a standardised protocol (Supplementary file 1), using a Siemens PrismaFit 3.0-T MRI, and a Philips Ingenia 3.0-T MRI. All scans were performed in standard supine ankle plantigrade position in a dedicated ankle coil. Non-contrast-enhanced MRI was used as it is non-invasive. Images were de-identified and stored on a picture archive and communication system for online analysis using imaging analysis software (InteleViewer version 4.18.1.0). Imaging reporting was conducted according to a pre-determined MRI scoring tool (Supplementary file 2). The selection of MRI features was based on those commonly described in the PAIS literature. All images were reported by a senior musculoskeletal radiologist with over 20 years’ experience, blinded to participant identification, age, sex, and group. Intraobserver reliability was assessed by re-scoring 10 randomly selected scans 3 months following completion of the initial scoring. A second blinded musculoskeletal radiologist scored the same 10 images to test interobserver reliability.

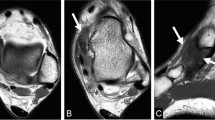

For all participants, the following features were identified as present or absent on MRI: posterior ankle bone marrow oedema, os trigonum, increased signal at the synchondrosis between the os trigonum and posterior talus, Stieda process, posterior talocrural joint effusion-synovitis, posterior subtalar joint effusion-synovitis, flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon pathology, and FHL tenosynovitis (Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 4 and Supplementary file 2). The presence of bone marrow oedema in an os trigonum (Fig. 1) or Stieda process was noted as present or absent. The posterior ankle region was defined as the posterior half of the tibial plafond, the posterior half of the talar dome, and the inferior talus and superior calcaneum of the posterior subtalar joint. Joint effusion-synovitis was defined as the presence of hyperintense signal changes with increased thickness or volume [33]. As contrast enhancement was not used, effusion and synovitis could not be differentiated [33]. If present, posterior talocrural joint effusion-synovitis size was measured as the maximum distance perpendicular to the slope of the talar dome in the sagittal plane (Fig. 5), and posterior subtalar joint effusion-synovitis size was measured as the maximum distance perpendicular to the calcaneal slope in the sagittal plane (Fig. 6). An os trigonum was defined as the presence of an ununited bone immediately posterior to the lateral tubercle of the posterior talar process [17]. A Stieda process was defined as an enlarged or elongated lateral talar process [17]. The size of an os trigonum or Stieda process was not reported. The radiologist identified and classified the findings of os trigonum and Stieda process separately, then these data were analysed both separately and in combination. It has been suggested that both structures originate within the same cartilaginous extension of the talus [34]. The presence of an os trigonum or Stieda process was combined into a single variable to reflect their shared clinical implications for PAIS as potential space-occupying bony structures within the posterior tibiocalcaneal interval. Flexor hallucis longus tendon pathology was defined as any abnormal signal within the FHL tendon [35]. Flexor hallucis longus tenosynovitis was defined as any sudden cut-off of the fluid within the synovial sheath at the level of the posterior talus [35]. There are potential communications between the FHL tendon synovial sheath and ankle joint [36]; therefore, it was impossible to assess for FHL tenosynovitis in isolation.

A 32-year-old male dancer. Sagittal SPAIR image demonstrates bone marrow oedema in the posterior tibia (circled), an os trigonum with bone marrow oedema (arrow), increased signal at the synchondrosis (arrowhead), and posterior talocrural and subtalar joint effusion-synovitis (asterisk). Ti tibia, Ta talus, C calcaneum

Ethics approval was granted by the La Trobe University Human Ethics Committee (HEC16-123). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Statistical analysis

All data analysis was performed using statistical software (SPSS version 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Participant demographic data were assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the group comparisons made (dancers versus athletes) using the independent samples t-test for parametric, and Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric data. The prevalence of each MRI finding was reported for each group (dancer or athlete), then by sub-groups (e.g. male versus female dancers) and compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test. Posterior joint effusion-synovitis sizes were assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test, between group and sex comparisons made using the Mann–Whitney U test. The P value was set at < 0.05.

Imaging scoring reliability was calculated using Cohen’s kappa for categorical data or intraclass correlation coefficient for continuous data. In instances where kappa was unable to be calculated (i.e. if each participant tested was scored the same rating), reliability was presented as numbers of agreement. A negative kappa indicated poorer than chance agreement [37]. A kappa value between 0 and 0.2 was deemed slight agreement, between 0.21 and 0.4 fair agreement, between 0.41 and 0.6 moderate agreement, between 0.61 and 0.8 substantial agreement, between 0.81 and 0.99 almost perfect agreement, and 1 as perfect agreement [38]. Intraclass correlation coefficient values of less than 0.40 suggested poor reliability, between 0.40 and 0.59 fair reliability, between 0.60 and 0.74 good reliability, and between 0.75 and 1.00 excellent reliability [39].

Results

Participants

Both groups (dancers and athletes) were comparable in age, height, years of professional experience, and history of lateral ankle sprain; however, dancers had significantly lower weight and body mass index than athletes (P < 0.01) and commenced training at least four times per week at a significantly younger age (P < 0.01) (Table 1). For the current level of function in the ankle imaged, 58 participants (76%) answered normal, 17 (22%) answered nearly normal, 1 (1%) answered abnormal, and 0 answered severely abnormal.

Imaging scoring reliability testing

For all categorical MRI scoring variables, there was at least moderate interobserver and intraobserver agreement, except FHL tenosynovitis (ĸ = − 0.15 and ĸ = − 0.18, respectively) and increased signal at the synchondrosis between os trigonum and talus (ĸ = 0.23, ĸ = 0.43, respectively) (Table 2). Kappa was indeterminate for two variables: posterior talocrural joint effusion-synovitis and FHL tendon pathology because at least one rater assigned each participant the same score. For these two variables, the agreement was at minimum eight out of ten. Posterior talocrural joint effusion-synovitis size demonstrated poor to moderate reliability; however, posterior subtalar joint effusion-synovitis size ranged from acceptable to excellent reliability.

MRI results

There were 35 right (dancer n = 22, athlete n = 13) and 41 left (dancer n = 16, athlete n = 25) ankle MRIs. Imaging features were highly prevalent in both groups (Table 3). The most common MRI features were posterior subtalar joint effusion-synovitis and posterior talocrural joint effusion-synovitis, present in 93.4% and 90.8% of all participants, respectively. Overall os trigonum prevalence was 27.6%, and Stieda process prevalence was 34.2%, equating to 61.8% of participants having either an os trigonum or Stieda process. Bone marrow oedema was more prevalent in the os trigona than in the Stieda processes, with bone marrow oedema in nine of the 21 os trigona (42.9%), compared to three of the 26 Stieda processes (11.5%). The proportion of os trigona that had increased signal at the synchondrosis was 66.7% (75% and 61.5% in dancers and athletes, respectively).

Dancers versus athletes

The prevalence of most MRI findings was similar between dancers and athletes (Table 3). Athletes had a higher prevalence of either an os trigonum or Stieda process compared to dancers (P = 0.03). This was largely moderated by the male athletes who had a higher prevalence of os trigonum or Stieda process (90%) compared to male dancers (50%) (P = 0.01). Within the athlete group, the female fast bowlers had a lower prevalence of either an os trigonum or Stieda process (25%) compared to the female soccer players (80%). The median posterior subtalar joint effusion size was larger in dancers than athletes (P = 0.02). Female dancers had larger posterior subtalar joint effusions than female athletes (P = 0.01); male dancers and male athletes had similar posterior subtalar joint effusion sizes.

Men versus women

No significant differences were found between the MRIs of male and female dancers. Male athletes had a higher prevalence of os trigonum or Stieda process (90%) compared to female athletes (50%) (P = 0.02, Table 3). This appeared to be driven by the relatively low numbers of os trigonum or Stieda process in female fast bowlers.

Discussion

This study provides insight into the prevalence of posterior ankle MRI findings in people undertaking different forms of elite physical activity at full workloads. Posterior talocrural and subtalar joint effusion-synovitis were highly prevalent, as well as the presence of either an os trigonum or Stieda process. Athletes had a higher prevalence of os trigonum or Stieda process compared to dancers, whereas dancers demonstrated larger posterior subtalar joint effusions than athletes. This information suggests that these MRI findings may represent a response to activity-specific load exposure rather than pathology in a typical elite athletic and dance population.

Male athletes had a higher prevalence of either an os trigonum or Stieda process than both male dancers and female athletes. The presence of an os trigonum or Stieda process could represent a typical finding in these elite male athletes. It has been suggested that the osseous development of the posterior talus may be influenced by activity performed prior to skeletal maturation [1, 19, 40]. In this study, the ballet dancers commenced more frequent training at a younger age than athletes yet surprisingly had a lower prevalence of os trigonum or Stieda process. Ballet dancers perform jump propulsion and landing through positions of extreme ankle plantarflexion and undertake repetitive and sustained full weight-bearing in end-range plantarflexion. Cricket fast bowlers and soccer players’ ankles generally do not achieve such extremes of range [21, 23]; however, they are exposed to rapid ankle deformation with high force in open- and closed-chain positions [24]. Perhaps osseous development is influenced by factors such as exposure to repeated high peak ground reaction forces that appear to be higher in fast bowlers and soccer players [24, 26] than in ballet dancers [27, 28]. Another possible explanation for the lower prevalence of os trigonum or Stieda process in dancers is that dancers with prominent osseous extrusions may not be able to achieve the extreme ankle plantarflexion required to continue to professional status. This may be an example of attrition bias in ballet dancers. In this study, os trigonum prevalence in dancers was similar to that previously cited in the general population [17, 41]; therefore, an os trigonum in an aspiring young dancer should not be considered career-threatening. Previous literature on non-sporting populations has reported similar rates of os trigonum in men and women [15, 17], whereas other studies report a higher prevalence in men [16, 42]. Male fast bowlers have been demonstrated to generate higher peak vertical and horizontal ground reaction forces than female fast bowlers [29], which may be a contributing factor to the significantly higher prevalence of os trigonum or Stieda process in male athletes. Male and female dancers had similar MRI findings; therefore, factors common to both sexes such as hypermobility [43], the demi-pointe position (full weight-bearing at end-range ankle plantarflexion), or jumping may be greater contributors than pointe shoes to the development of PAIS-associated imaging findings in ballet dancers.

Posterior subtalar joint effusion-synovitis has been implicated in PAIS and has been described in symptomatic ballet dancers [1, 44], soccer players [45], and other athletes [6]. The definition and measurement of subtalar joint effusion-synovitis vary between studies, and there are no published data on effusion sizes in PAIS. In this study, a very high proportion of participants demonstrated posterior talocrural or subtalar joint effusion-synovitis. In the general population, the presence of talocrural and subtalar articular fluid is a common MRI finding despite symptom status and should not be considered atypical [36]. In a previous study of 23 dancers diagnosed with PAIS, posterior talocrural synovitis was found in 100% of participants [1]. This study supports that the presence of posterior talocrural and subtalar joint effusion-synovitis may be typical MRI findings in elite athletes and dancers, perhaps representing a response to chronic subtalar joint loading, or chronic instability following repeated ankle sprains [46,47,48] rather than PAIS-specific pathology.

In this study, previous lateral ankle sprain was common in both groups, which may have been a contributing factor to the high prevalence of effusion-synovitis. The larger effusion-synovitis sizes in dancers may be due to increased loading through the subtalar joint or increased subtalar joint translation due to hypermobility or chronic laxity [49]. Previous en pointe MRI studies have demonstrated apparent anterior talar translation underneath the tibia associated with posterior convergence of the distal tibia and superior calcaneum in end-range plantarflexion [20, 50]. Translations at the subtalar joint have not been compared between dancers and athletes; however, greater effusion size in dancers may indicate a ballet-specific sub-category of PAIS.

It is possible that activity-specific loading patterns, both prior to and after skeletal maturation, contribute to distinct posterior ankle morphology and pathology detected on MRI in dancers and sportspeople. Future longitudinal research in skeletally immature athletes and dancers could provide insight into the effects of ankle loading on the osseous development of the posterior talus.

This study utilised an optimised 3.0-T MRI protocol to collect high-quality images. Imaging scoring reliability testing was acceptable for all MRI features except for poor interobserver and intraobserver reliability for the presence of FHL tenosynovitis, the size of talocrural joint effusion-synovitis, and fair interobserver reliability for an increased signal at the os trigonum synchondrosis; therefore, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Conventional radiographs have a lower sensitivity for identifying an os trigonum or Stieda process and may explain why the prevalence of these findings in this study was higher than in other studies. Furthermore, there is no accepted cut-off length for classification as a Stieda process in any imaging modality [16, 17, 19], and this may explain the variation in prevalence between this and other studies. The preferential imaging of feet with a history of symptoms may have introduced selection bias, resulting in a greater prevalence of imaging findings than only imaging feet with no history of injury/symptoms.

A high prevalence of PAIS-associated MRI findings was found in dancers and athletes performing at full workloads. It is possible that these findings may simply reflect chronic exposure to high ankle loads. Trends were observed between different groups, with male athletes having a higher prevalence of os trigonum or Stieda process, and dancers having larger posterior subtalar joint effusion-synovitis. These findings imply that there may be sub-categories of PAIS based on activity-type exposure and sex-based biomechanics. Future longitudinal research in skeletally immature male and female athletes and dancers would determine the effects of activity on the osseous development of the posterior talus.

References

Peace KAL, Hillier JC, Hulme A, Healy JC. MRI features of posterior ankle impingement syndrome in ballet dancers: a review of 25 cases. Clin Radiol. 2004;59(11):1025–33.

Hamilton W. Pain in the posterior aspect of the ankle in dancers. Differential diagnosis and operative treatment. J Bone Jt Surgery. 1996;78(10):1491–500.

Brodsky AE, Khalil MA. Talar compression syndrome. Foot Ankle. 1987;7(6):338–44.

Wredmark T, Carlstedt CA, Bauer H, Saartok T. Os trigonum syndrome: a clinical entity in ballet dancers. Foot Ankle. 1991;11(6):404–6.

Marotta JJ, Micheli LJ. Os trigonum impingement in dancers. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20(5):533–6.

Bureau NJ, Cardinal E, Hobden R, Aubin B. Posterior ankle impingement syndrome: MR imaging findings in seven patients. Radiology. 2000;215(2):497–503.

Ribbans WJ, Ribbans HA, Cruickshank JA, Wood EV. The management of posterior ankle impingement syndrome in sport: a review. Foot Ankle Surg. 2015;21(1):1–10.

Kalbouneh HM, Alajoulin O, Alsalem M, et al. Incidence of symptomatic os trigonum among nonathletic patients with ankle sprain. Surg Radiol Anat. 2019;41(12):1433–9.

Mansingh A. Posterior ankle impingement in fast bowlers in cricket. West Indian Med J. 2011;60(1):77–81.

Calder JD, Sexton SA, Pearce CJ. Return to training and playing after posterior ankle arthroscopy for posterior impingement in elite professional soccer. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(1):120–4.

Hedrick MR, McBryde AM. Posterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15(1):2–8.

Hamilton W. Stenosing tenosynovitis of the flexor hallucis longus tendon and posterior impingement upon the os trigonum in ballet dancers. Foot Ankle. 1982;3(2):74–80.

Messiou C, Robinson P, O’Connor PJ, Grainger A. Subacute posteromedial impingement of the ankle in athletes: MR imaging evaluation and ultrasound guided therapy. Skeletal Radiol. 2006;35(2):88–94.

van Dijk CN, Scholten PE, Krips R. A 2-portal endoscopic approach for diagnosis and treatment of posterior ankle pathology. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(8):871–6.

Coskun N, Yuksel M, Cevener M, et al. Incidence of accessory ossicles and sesamoid bones in the feet: a radiographic study of the Turkish subjects. Surg Radiol Anat. 2009;31(1):19–24.

Cicek ED, Bankaoglu M. Prevalence of elongated posterior talar process (Stieda process) detected by radiography. Int J Morphol. 2020;38(4):894–8.

Zwiers R, Baltes TPA, Opdam KTM, Wiegerinck JI, van Dijk CN. Prevalence of os trigonum on CT imaging. Foot Ankle Int. 2018;39(3):338–42.

Zwiers R, Dobbe JGG, Streekstra GJ, et al. Exorotated radiographic views have additional diagnostic value in detecting an osseous impediment in patients with posterior ankle impingement. Jt Disord Orthop Sport Med. 2019;4(4):181–7.

Fu X, Ma L, Zeng Y, et al. Implications of classification of os trigonum: a study based on computed tomography three-dimensional imaging. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:1423–8.

Russell JA, Shave RM, Yoshioka H, Kruse DW, Koutedakis Y, Wyon MA. Magnetic resonance imaging of the ankle in female ballet dancers en pointe. Acta Radiol. 2010;51(6):655–61.

Felton PJ, Lister SL, Worthington PJ, King MA. Comparison of biomechanical characteristics between male and female elite fast bowlers. J Sport Sci. 2019;37(6):665–70.

Russell JA, Shave RM, Kruse DW, Koutedakis Y, Wyon MA. Ankle and foot contributions to extreme plantar- and dorsiflexion in female ballet dancers. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(2):183–8.

Tol JL, Slim E, van Soest AJ, van Dijk CN. The relationship of the kicking action in soccer and anterior ankle impingement syndrome. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(1):45–50.

Spratford W, Hicks A. Increased delivery stride length places greater loads on the ankle joint in elite male cricket fast bowlers. J Sport Sci. 2014;32(12):1101–9.

Worthington P, King M, Ranson C. The influence of cricket fast bowlers’ front leg technique on peak ground reaction forces. J Sport Sci. 2013;31(4):434–41.

Orloff H, Sumida B, Chow J, Habibi L, Fujino A, Kramer B. Ground reaction forces and kinematics of plant leg position during instep kicking in male and female collegiate soccer players. Sport Biomech. 2008;7(2):238–47.

Walter HL. Ground reaction forces in ballet dancers landing in flat shoes versus pointe shoes. J Danc Med Sci. 2011;15(2):61.

McPherson AM, Schrader JW, Docherty CL. Ground reaction forces in ballet differences resulting from footwear and jump conditions. J Danc Med Sci. 2019;23(1):34–9.

Stuelcken MC, Sinclair PJ. A pilot study of the front foot ground reaction forces in elite female fast bowlers. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12(2):258–61.

Clarsen B, Rønsen O, Myklebust G, Flørenes TW, Bahr R. The Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center questionnaire on health problems: a new approach to prospective monitoring of illness and injury in elite athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(9):754–60.

Bahr R. No injuries, but plenty of pain? On the methodology for recording overuse symptoms in sports. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(13):966–72.

Harringe ML, Lindblad S, Werner S. Do team gymnasts compete in spite of symptoms from an injury? Br J Sports Med. 2004;38(4):398–401.

Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Crema MD, Englund M, Hayashi D. Imaging of non-osteochondral tissues in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cart. 2014;22(10):1590–605.

Knapik DM, Guraya SS, Jones JA, Cooperman DR, Liu RW. Incidence and fusion of os trigonum in a healthy pediatric population. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39(9):e718–21.

Gursoy M, Dag F, Mete BD, Bulut T, Uluc ME. The anatomic variations of the posterior talofibular ligament associated with os trigonum and pathologies of related structures. Surg Radiol Anat. 2015;37(8):955–62.

Schweitzer ME, van Leersum M, Ehrlich SS, Wapner K. Fluid in normal and abnormal ankle joints: amount and distribution as seen on MR images. Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162(1):111–4.

Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):37–46.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74.

Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(4):284–90.

McDougall A. The os trigonum. J Bone Jt Surgery. 1955;37(2):257–65.

Tsuruta T, Shiokawa Y, Kato A, et al. Radiological study of the accessory skeletal elements in the foot and ankle (author’s transl). Nihon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi. 1981;55(4):357–70.

Ozer M, Yildirim A. Evaluation of the prevalence of os trigonum and talus osteochondral lesions in ankle magnetic resonance imaging of patients with ankle impingement syndrome. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;58(2):273–7.

McCormack M, Briggs J, Hakim A, Grahame R. Joint laxity and the benign joint hypermobility syndrome in student and professional ballet dancers. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(1):173–8.

Russell JA, Kruse DW, Koutedakis Y, Mcewan IM, Wyon MA. Pathoanatomy of posterior ankle impingement in ballet dancers. Clin Anat. 2010;23(6):613–21.

Kudas S, Donmez G, Isik C, Celebi M, Cay N, Bozkurt M. Posterior ankle impingement syndrome in football players: case series of 26 elite athletes. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2016;50(6):649–54.

Kobayashi T, Gamada K. Lateral ankle sprain and chronic ankle instability. Foot Ankle Spec. 2014;7(4):298–326.

Hertel J. Functional instability following lateral ankle sprain. Sport Med. 2000;29(5):361–71.

Hertel J, Denegar CR, Monroe MM, Stokes WL. Talocrural and subtalar joint instability after lateral ankle sprain. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 1999;31(11):1501–8.

Ménétrey J, Fritschy D. Subtalar subluxation in ballet dancers. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(2):143–9.

Russell JA, Yoshioka H. Assessment of female ballet dancers’ ankles in the en pointe position using high field strength magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Radiol. 2016;57(8):978–84.

Acknowledgements

A sincere thank you to the dancers and athletes of The Australian Ballet, Cricket Australia, Cricket Victoria and Melbourne City Football Club for their participation in this study. The authors sincerely thank A. Kountouris of Cricket Australia for his collaborative efforts; K. Sims, N. Adcock, M. Tucker, D. Stanborough, L. Kennedy, L. Poon, and B. Robertson for assisting in participant recruitment; S. Emery, M. Hook, V. Tran, and J. Baillie for their assistance with data collection; A. Garnham, J. Walsh and T. O’Shea for their assistance in image acquisition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baillie, P., Cook, J., Ferrar, K. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings associated with posterior ankle impingement syndrome are prevalent in elite ballet dancers and athletes. Skeletal Radiol 50, 2423–2431 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-021-03811-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-021-03811-x