Abstract

Objective

In neurolymphomatosis (NL), the affected nerves are typically described to be enlarged and hyperintense on T2W MR sequences and to avidly enhance on gadolinium-enhanced T1WI. This pattern is highly non-specific. We recently became aware of a “tumefactive pattern” of NL, neuroleukemiosis (NLK) and neuroplasmacytoma (NPLC), which we believe is exclusive to hematologic diseases affecting peripheral nerves.

Materials and methods

We defined a “tumefactive” appearance as complex, fusiform, hyperintense on T2WI, circumferential tumor masses encasing the involved peripheral nerves. The nerves appear to be infiltrated by the tumor. Both structures show varying levels of homogenous enhancement. We reviewed our series of 52 cases of NL in search of this pattern; two extra outside cases of NL, three cases of NLK, and one case of NPLC were added to the series.

Results

We identified 20 tumefactive lesions in 18 patients (14 NL, three NLK, one NPLC). The brachial plexus (n = 7) was most commonly affected, followed by the sciatic nerve (n = 6) and lumbosacral plexus (n = 3). Four patients had involvement of other nerves. All were proven by biopsy: the diagnosis was high-grade lymphoma (n = 12), low-grade lymphoma (n = 3), acute leukemia (n = 2), and plasmacytoma (n = 1).

Conclusions

We present a new imaging pattern of “tumefactive” neurolymphomatosis, neuroleukemiosis, or neuroplasmacytoma in a series of 18 cases. We believe this pattern is associated with hematologic diseases directly involving the peripheral nerves. Knowledge of this association can provide a clue to clinicians in establishing the correct diagnosis. Bearing in mind that tumefactive NL, NLK, and NPLC is a newly introduced imaging pattern, we still recommend to biopsy patients with suspicion of a malignancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hematologic disorders affecting peripheral nerve represent a curious group of disorders that are frequently misdiagnosed and underdiagnosed. Neurolymphomatosis (NL), lymphomatous infiltration of peripheral nerves, though rare, is more common than widely considered, with reported series up to 50 cases [1]. It occurs predominantly in patients with intermediate or high-grade forms of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), and most frequently in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [2]. Its relative incidence is not well studied, but is estimated to represent 10 % of primary lymphoma of the nervous system (0.2 % of all NHL), and to occur in 0.9–3 % of patients with intermediate or high-grade NHL [2, 3]. Neuroleukemiosis (NLK) is a rarely reported manifestation of leukemia with only individual case reports or small series reported. The same is true for exceedingly rare plasmacytoma affecting peripheral nerves (we propose the term neuroplasmacytoma, NPLC). Symptoms from any of these hematologic malignancies can vary greatly, ranging from asymptomatic involvement to complete nerve palsy with or without neuropathic pain. Based on the localization, the neurologic deficit can be further subclassified ranging from polyradiculopathy or polyneuropathy to cranial neuropathy or mononeuropathy [2, 4–7]. The diagnosis of NL or other hematologic malignancies can be enigmatic, especially in primary disease. MRI plays a crucial role in the evaluation of peripheral nervous diseases: it helps to not only better localize the disease (and improve the yield of a targeted biopsy) but can also give valuable clues to identify the etiology. For the most common of these disorders, the nerves are typically described to demonstrate different levels of enlargement, hyperintensity on T2W sequences, and to enhance after intravenous contrast (Fig. 1a,b). This appearance is non-specific and can be seen in inflammatory (Fig. 1c), toxic, or radiation injury or in other benign or malignant neurogenic (Fig. 1d) or non-neurogenic tumors.

A similar appearance of different conditions. A sagittal T2W fat-suppressed (T2 FS) MR image (a) demonstrating a large and hyperintense left brachial plexus in a patient with NL, a pattern typically described, but non-specific. An axial gadolinium-enhanced spoiled gradient recall echo (SPGR) image (b) of a different patient with NL shows an enlarged and avidly enhancing left sciatic nerve (b, arrowhead); again, an appearance typical, but not specific for NL. Similar characteristics are demonstrated in other entities such as chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (c, T2 FS MRI; arrowhead) or a sarcoma extending from the brachial plexus to the spinal nerves (d, gadolinium-enhanced SPGR image; arrowheads)

The aim of this work is to report a recently recognized radiologic (MRI and ultrasound) appearance, resulting in a “tumefactive” pattern of peripheral nerve lesions in a subgroup of patients with hematologic malignancies.

Materials and methods

After securing an institutional review board approval, our institutional series of all cases of NL (n = 52) diagnosed between 1998 and 2014 was retrospectively reviewed. Only cases with high-resolution MRI, which allowed for detailed neural anatomy, were included (n = 41). Cases without MRI studies or with low-quality MRI were excluded (n = 11), although four cases of these were suggestive of the tumefactive appearance. These are discussed in the Discussion section. Three extra cases of NLK and one case of NPLC were provided by the senior author (RJS) and two more cases of NL by co-authors (MNHB, CM). These cases were added to the series based on their known appearance. All cases were histologically proven. Demographic (sex, age) and clinical data (relevant history, time points, symptoms, imaging finding and biopsy) for each case were collected. Time-to-symptoms is defined as time from the original diagnosis to the first occurrence of neurological symptoms.

All cases were reviewed in detail by a senior musculoskeletal radiologist experienced in peripheral nerve imaging (KKA). All patients were imaged using MRI and only lesions with tumefactive pattern on MRI were included. We defined “tumefactive” pattern as: “complex, fusiform, circumferential masses encasing the involved peripheral nerves. The masses are hyperintense on T2W sequences, with intensity equal or more to the involved nerve, and demonstrate varying degree of homogenous enhancement on post-gadolinium scans. The nerves themselves are enlarged, hyperintense on T2W sequences, and demonstrated enhancement following intravenous gadolinium. The nerves appear to be infiltrated by the tumor, causing separation of individual fascicles, but the fascicles themselves are well preserved.” Only cases fulfilling the definition in all aspects were included. Where available, ultrasound and 18-fluorodeoxyglucose ositron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG PET/CT) findings were recorded, but are considered additional imaging studies. Similarly, the tumefactive appearance on ultrasound examination is defined as hypoechogenic enlarged nerves with preserved fascicular structure surrounded by a soft tissue mass, which is isoechogenic to nerve, but hypoechogenic to muscle. While there is no established absolute SUV threshold in the literature regarding the diagnosis of NL, normal skeletal muscle has been used as an internal reference for increased uptake on FDG PET/CT.

A literature search was performed to find other similar cases. The search was performed using the PubMed and Google Scholar search engines, without specified time-frame and with the main keywords being “neurolymphomatosis”, “neuroleukemiosis” or “lymphoma”, “leukemia”, “plasmacytoma” or “myeloma” combined with “neuropathy”. Only articles with images were reviewed.

Results

We identified 20 “tumefactive” lesions in 18 patients (Table 1): in 12/52 cases of the institutional NL series; in 2/2 outside cases of NL, in 3/3 cases of NLK, and in 1/1 case of NPLC. Three cases (#1, #12, #13) were previously described elsewhere [8, 9], but in neither of these reports was the tumefactive appearance appreciated. The mean age was 64.4 years (range, 47–85 years). Nine patients were female and nine male. Patients presented differently: as a recurrence after a period of remission (n = 7), as the first symptom of a systemic disease (n = 5), neurological involvement during course of the disease (n = 3), and as primary NL or NLK (n = 3). Ten patients were diagnosed with a hematologic malignancy prior to presentation: DLBCL was the most common original diagnosis (n = 6); others were mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue lymphoma (MALT)(n = 1), lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (LPL) (n = 1), multiple myeloma (MM) (n = 1), and unspecified non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL NOS)(n = 1). In these patients, the mean time-to-symptoms was 42.4 months (range, 7–132 months). On examination, the patients typically presented with weakness (n = 15), numbness (n = 10), pain (n = 10), or paresthesias (n = 6). Two patients had no neurological symptoms and presented with local swelling/mass symptoms. The brachial plexus (n = 7) was most commonly affected, followed by the sciatic nerve (n = 6) and lumbosacral plexus (n = 3). Four patients had involvement of other nerves.

In addition to MRI, which was available for all 18 patients, FDG PET/CT was available for 17 patients and ultrasound for one (case #3). FDG PET/CT demonstrated increased uptake in all lesions imaged with MRI and revealed two extra peripheral nerve lesions (cases #2 and #12) that were not imaged with MRI and we cannot comment on their appearance. All lesions scanned with MRI were of tumefactive appearance except one (case #16 had tumefactive brachial plexus lesion on left and non-tumefactive on right). Ultrasound demonstrated both tumefactive lesions in patient #3 in even greater detail. At the time of presentation, of these 18 patients, eight had only peripheral nervous system involvement, three peripheral and central nervous involvement, and seven had generalized disease.

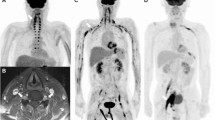

Biopsy was performed and was positive in all cases (n = 18); in eight cases it confirmed original diagnosis, in eight newly detected cases it was diagnostic, and in two it revealed a different subtype of NHL from the original diagnosis. The final diagnosis was DLBCL (n = 12), AML (n = 2), MALT lymphoma (n = 1), low-grade NHL NOS (n = 1), low-grade NHL with plasmacytic differentiation (n = 1) and plasmacytoma (n = 1). Imaging illustrations of tumefactive low-grade NL (Fig. 2), high-grade NL (Fig. 3) including ultrasound appearance (Fig. 4), NLK (Fig. 5), and NPLC (Fig. 6) are provided.

Imaging of a 67-year-old woman with low-grade (MALT) NL. An axial T2 FS MR image (a) demonstrates the enlarged tibial and peroneal portions of the right sciatic nerve surrounded by a hyperintense soft tissue lymphomatous mass (a, arrowhead). The mass and the nerve show similar level of enhancement (b, arrowhead) on gadolinium-enhanced spoiled gradient recall echo (SPGR) sequences (b). An anterio-posterior FDG PET scan (c) demonstrates elongated/spindle-like foci of increased uptake in the both lower extremities and in the left upper extremity suggestive of lymphomatous involvement of the both sciatic nerves and the left sensory radial nerve (c, arrowheads). A coronal T2 FS image (d) shows an elongated soft tissue mass (d, arrowheads) located along the right sciatic nerve (d, arrow). A coronal T2 FS image (e) of the left forearm demonstrates a soft tissue tumorous mass circumferentially encompassing the enlarged and hyperintense radial sensory nerve (e, arrowhead). An intraoperative photograph (f) shows a right sciatic nerve tumor, which macroscopically appeared to be confined to the sciatic nerve proximally (f, white asterisk), but with extraepineural extension distally (f, black asterisk)

Imaging of an 85-year-old woman with high-grade (DLBCL) neurolymphomatosis. An axial T2 FS image (a) of the right thigh demonstrates a massively enlarged right sciatic nerve circumferentially surrounded by a soft tissue mass worrisome for NL (a, the white square marks details presented in b). The sciatic nerve appears to be infiltrated by the tumor, but to have preserved fascicular architecture (b, “P” peroneal nerve; “T” tibial nerve; “A” femoral artery; “V” femoral vein). A sagittal T2 FS image (c) demonstrates the same tumorous mass (c, arrowhead) extending along the sciatic nerve (c, arrow) from the mid-thigh to the upper calf. The sciatic nerve and the surrounding tumor enhance avidly on the gadolinium-enhanced SPGR image (d, arrowhead). An axial T2 FS image (e) at the level of the popliteal fossa shows the tumor (e, arrowhead) encompassing the compressed popliteal artery (e, arrow); the popliteal vein is not visible due to compression. A coronal FDG PET (f) scan shows the area of increased uptake extending along the right sciatic nerve (f, arrowhead)

Imaging of a 53-year-old woman with high-grade NL (DLBCL). An axial T2 FS MR image (a) demonstrates bilateral enlargement of the sciatic nerves, which are infiltrated as well as surrounded by a soft tissue tumor mass (a, arrowheads). Ultrasound images in the perpendicular (b, d) and parallel plane (c, e) to the sciatic nerve show the enlarged nerve (b, d, arrowhead) with preserved fascicles (c, e, arrowheads) widely separated by the infiltrating tumor. The tumor is encased in a soft tissue tumor mass (b, c, asterisks). d, e Earlier stages of the same disease

Imaging of a 70-year-old man with NLK. A sagittal gadolinium-enhanced SPGR image of the left brachial plexus (a) demonstrates an enhancing tumor mass (a, arrowhead) circumferentially encompassing the enlarged and to a lesser degree enhancing posterior cord (a, arrow). A similar sagittal T2 FS image (b) shows the enlarged and hyperintense posterior cord (b, arrow) surrounded by a hyperintense lymphomatous mass (b, arrowhead). A coronal FDG PET scan (c) demonstrates increased uptake along the left brachial plexus (c, arrowhead). A coronal oblique gadolinium-enhanced SPGR image (d) shows the enlarged left radial nerve (d, arrow) and the axillary artery surrounded by an enhancing soft tissue tumorous mass (d, arrow). A coronal T2 FS image (e) demonstrates the same hyperintense lesion (e, arrowhead) encompassing the large radial nerve (e, arrow) and the axillary artery. An intraoperative photograph (f) shows the massively enlarged posterior cord of the left brachial plexus (f, asterisk)

Imaging of a 60-year-old woman with NPLC. An axial T2 FS axial of the right thigh demonstrates the markedly enlarged, hyperintense, and infiltrated right sciatic nerve (a, arrow) circumferentially surrounded by a soft tissue tumorous mass (a, arrowhead), which together with the nerve avidly enhances on axial gadolinium-enhanced SPGR images (b, arrowhead). A coronal T2 FS MR image (c) shows the same tumorous mass (c, arrowhead) encompassing the sciatic nerve (c, arrow) and extending from the lumbosacral plexus to the upper thigh. A coronal combined FDG PET/CT image demonstrates an area of increased uptake (d, arrowhead), which correlates with the same tumor mass seen on MR images

Discussion

We describe a new “tumefactive” imaging pattern of peripheral nerve involvement of hematologic malignancies, including lymphoma, leukemia, and plasmacytoma. All lymphomas in this series were of B-cell lineage, but a similar appearance of T-cell NL [10–12] could be appreciated on images in our review of the literature. Similarly, we demonstrated this tumefactive appearance on ultrasound. FDG PET/CT can reveal more widespread disease or confirm a solitary lesion and thus alter management of the patients. None of the authors has encountered similar imaging appearance in any other disease in our practice. Although some tumors could be described as with “preserved fascicular structure” (e.g., plexiform schwannomas or perineuriomas) and some as “encasing the nerves” (e.g., typically metastatic cancers as melanoma), a review of more than 200 cases of neurogenic as well as non-neurogenic peripheral nerve tumors treated at our institution failed to demonstrate the similar appearance.

We have demonstrated that this radiologic pattern is not an uncommon manifestation in patients with NL, although given the design of our study, it is difficult to comment on prevalence. In addition to the nine cases of NL that were discovered by review of our institutional series (n = 52), four other cases demonstrated imaging findings highly suggestive of tumefactive NL, but could not be included, as the imaging was of low resolution and did not allow for detailed evaluation. The same pattern was seen in all three patients with NLK and the one with NPLC. In addition, our literature search confirmed the “commonness” of tumefactive NL, NLK, and NPLC: we found this same MRI and ultrasound pattern in reports of B-cell lymphomas [13–23], T-cell lymphomas [10–12], acute myeloid [24–29], as well as lymphocytic [30, 31] leukemias and plasmacytomas [32, 33].

Neither the underlying mechanism to explain this tumefactive appearance nor the prognostic value is known. Two explanations of NL reported in the literature are either extrinsic infiltration of the nerve with circulating tumor cells expressing “homing” receptors or lymphoma intrinsically arising in the nerve after finding a sanctuary in the endoneurium [2, 34]. The homing theory would be clinically supported by multifocal or diffuse involvement. On the other, the “sanctuary” theory would explain localized character of tumefactive NL, NLK, and NPLC. This latter theory is supported by cases of lymphoma or leukemia that relapsed within peripheral nerves, while a relapse soon after chemotherapy could be explained by chemically privileged environment of the endoneurium and recurrence after several years by escape from the immune control after a longer period of “hiding” in the immunologically privileged endoneurium [35].

Nevertheless, none of these theories provides a satisfactory explanation for the tumefactive appearance; in theory, both can cause nerve infiltration and localized mass lesion. Four cases had available serial imaging (#2, #3, #10, and #16; mean interval, 2.2 months): cases #2 and #16 demonstrated only enlarged and enhancing nerves on the first occasion, but later they developed circumferential mass around the infiltrated nerves, cases #3 and #10 showed progressive tumefactive appearance (Fig. 4). What anatomic layer constrains the tumor is not clear. In some instances the tumor appears to be contained within the epineurium or possibly within the “paraneural sheath” [36] (Fig. 2a). Elsewhere, it encompasses the vessels, but retains round, non-invasive character, which would suggest infiltration of the sheath of the neurovascular bundle, but not beyond (Fig. 3e). In one instance (case #15), the tumor had an invasive character extending into the surrounding muscles. We propose that the tumor can break through the paraneural sheath and infiltrate the adjacent structures. Similar tumor behavior has been reported: Kim et al. [37] described a case of median nerve T-cell NL in which the tumor was confined to the epineurium. As per this report, in one segment the epineurium was ruptured and the tumor spread and invaded the adjacent structures. Based on these observations, we believe the tumor starts to grow inside the nerve and subsequently extends beyond the nerve and possibly beyond the paraneural sheath. None of the lesions in our series was resected in toto, but we believe on microscopic examination an extensive epineurial infiltrative process, separating nerve fascicles with different level of endoneurial invasion would have been demonstrated. A similar pattern can be seen in the articles with such pathological images [19, 20, 27, 28, 32, 37, 38].

The prognostic significance of this tumefactive pattern is still unknown. Misdraji et al. [34] reported a series of four cases of primary NL, two of which were, according to the description, highly suggestive of the same tumefactive appearance we have described. Both of these patients had alterations in the CDKN2A/p16 pathway and carried significantly worse prognosis, but this series is too small number to draw any conclusions.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. This series is not controlled with a parallel patient group and all cases were reviewed by a single radiologist. This study represents patients from a single tertiary institution with six extra cases added based on their known appearance, therefore this series is not representative in terms of prevalence of tumefactive appearance among all patients with hematologic malignancies involving peripheral nerves. Some tumefactive lesions might have been missed, as not all lesions positive on radioisotope studies were imaged with MRI (on the other hand, every patient included in the study had at least one lesion imaged with MRI). Although none of the authors is aware of a similar presentation in any other disease, we cannot exclude that another disease could not demonstrate the similar appearance.

Conclusions

We present a new imaging pattern of “tumefactive” neurolymphomatosis, neuroleukemiosis, or neuroplasmacytoma in a series of 18 cases. We believe this pattern is associated with hematologic diseases directly involving the peripheral nerves. Knowledge of this association can provide a clue to clinicians in establishing the correct diagnosis.

Abbreviations

- NL:

-

Neurolymphomatosis

- NLK:

-

Neuroleukemiosis

- NPLC:

-

Neuroplasmacytoma

- NHL:

-

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- DLBCL:

-

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- MALT:

-

Mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue lymphoma

- LG BCL with PD:

-

Low-grade B-cell lymphoma with plasmacytic differentiation

- LPL:

-

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma

- NOS:

-

Not otherwise specified

- AML:

-

Acute myelogenous leukemia

- W:

-

Weakness

- N:

-

Numbness

- P:

-

Pain

- Par:

-

Paresthesias

- MM:

-

Multiple myeloma

- FDG:

-

18-fluorodeoxyglucose

- PET/CT:

-

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography

References

Grisariu S, Avni B, Batchelor TT, van den Bent MJ, Bokstein F, Schiff D, et al. Neurolymphomatosis: an International Primary CNS Lymphoma Collaborative Group report. Blood. 2010;115(24):5005–11.

Baehring JM, Damek D, Martin EC, Betensky RA, Hochberg FH. Neurolymphomatosis. Neuro Oncol. 2003;5(2):104–15.

Gan HK, Azad A, Cher L, Mitchell PL. Neurolymphomatosis: diagnosis, management, and outcomes in patients treated with rituximab. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12(2):212–5.

Yazawa S, Ohi T, Shiomi K, Takashima N, Kyoraku I, Nakazato M. Brachial plexus neurolymphomatosis: a discrepancy between electrophysiological and radiological findings. Intern Med. 2007;46(8):533–4.

Rosso SM, de Bruin HG, Wu KL, van den Bent MJ. Diagnosis of neurolymphomatosis with FDG PET. Neurology. 2006;67(4):722–3.

Rahmani M, Birouk N, Amarti A, Loukili Idrissi A, Marnissi F, Belaidi H, et al. T-cell lymphoma revealed by a mononeuritis multiplex: case report and review of literature. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2007;163(4):462–70.

Kim JH, Jang JH, Koh SB. A case of neurolymphomatosis involving cranial nerves: MRI and fusion PET-CT findings. J Neurooncol. 2006;80(2):209–10.

Reddy CG, Mauermann ML, Solomon BM, Ringler MD, Jerath NU, Begna KH, et al. Neuroleukemiosis: an unusual cause of peripheral neuropathy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53(12):2405–11.

Mahan MA, Ladak A, Johnston PB, Seningen JL, Amrami KK, Spinner RJ. Unique occurrence of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma disseminated to peripheral nerves. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2013;22(4):321–5.

Hanna R, Di Primio GA, Schweitzer M, Torres C, Sheikh A, Chakraborty S. Progressive neurolymphomatosis with cutaneous disease: response in a patient with mycosis fungoides. Skelet Radiol. 2013;42(7):1011–5.

Agrawal S, Gi MT, Ng SB, Puhaindran ME, Singhania P. MRI and PET-CT in the diagnosis and follow-up of a lymphoma case with multifocal peripheral nerve involvement. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2013;19(1):25–8.

Kanamori M, Matsui H, Yudoh K. Solitary T-cell lymphoma of the sciatic nerve: case report. Neurosurgery. 1995;36(6):1203–5.

Baehring JM, Batchelor TT. Diagnosis and management of neurolymphomatosis. Cancer J. 2012;18(5):463–8.

Choi YJ, Shin JA, Kim YH, Cha SJ, Cho JY, Kang SH, et al. Neurolymphomatosis of brachial plexus in patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2013;2013:492329.

Peruzzi P, Ray-Chaudhuri A, Slone WH, Mekhjian HS, Porcu P, Chiocca E. Reversal of neurological deficit after chemotherapy in BCL-6-positive neurolymphomatosis. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(2):247–51.

Roncaroli F, Poppi M, Riccioni L, Frank F. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the sciatic nerve followed by localization in the central nervous system: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1997;40(3):618–21. discussion 621–612.

Descamps MJ, Barrett L, Groves M, Yung L, Birch R, Murray NM, et al. Primary sciatic nerve lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(9):1087–9.

Ye BS, Sunwoo IN, Suh BC, Park JP, Shim DS, Kim SM. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting as piriformis syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41(3):419–22.

Quinones-Hinojosa A, Friedlander RM, Boyer PJ, Batchelor TT, Chiocca EA. Solitary sciatic nerve lymphoma as an initial manifestation of diffuse neurolymphomatosis. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2000;92(1):165–9.

Eusebi V, Bondi A, Cancellieri A, Canedi L, Frizzera G. Primary malignant lymphoma of sciatic nerve. Report of a case. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14(9):881–5.

Wadhwa V, Thakkar RS, Maragakis N, Hoke A, Sumner CJ, Lloyd TE, et al. Sciatic nerve tumor and tumor-like lesions—uncommon pathologies. Skelet Radiol. 2012;41(7):763–74.

Suresh S, Saifuddin A, O'Donnell P. Lymphoma presenting as a musculoskeletal soft tissue mass: MRI findings in 24 cases. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(11):2628–34.

Wai JWC, Chan MK, Tang KW, Chan SCH. Neurogenic tumour mimicker: two cases of neurolymphomatosis. Hong Kong J Radiol. 2012;15:187–91.

Karam C, Khorsandi A, MacGowan DJ. Clinical reasoning: a 23-year-old woman with paresthesias and weakness. Neurology. 2009;72(2):e5–e10.

Warme B, Sullivan J, Tigrani DY, Fred DM. Chloroma of the forearm: a case report of leukemia recurrence presenting with compression neuropathy and tenosynovitis. Iowa Orthop J. 2009;29:114–6.

Bakst R, Jakubowski A, Yahalom J. Recurrent neurotropic chloroma: report of a case and review of the literature. Adv Hematol. 2011;2011:854240.

Lekos A, Katirji MB, Cohen ML, Weisman Jr R, Harik SI. Mononeuritis multiplex. A harbinger of acute leukemia in relapse. Arch Neurol. 1994;51(6):618–22.

Wang T, Miao Y, Meng Y, Li A. Isolated leukemic infiltration of peripheral nervous system. Muscle Nerve. 2015;51(2):290–93.

Zhu X-Y, Kuo S-H, Wan L-P, Liu Y, Wu Y-C. Isolated peripheral neuropathy as an unusual presentation for an extramedullary relapse of acute leukemia. Neurol Asia. 2014;19(2):203–6.

Hsu JH, Gordon C, Megason G, Majumdar S, Ostrenga A, Herrington B. A rare case of peripheral neuropathy from relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia to the brachial plexus. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34(2):e77–9.

Sui XF, Liu WY, Guo W, Xiao F, Yu X. Precursor B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia of the arm mimicking neurogenic tumor: case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:140.

Green RA, O'Donnell P, Briggs TW, Tirabosco R. Two malignant peripheral nerve lesions of non-neurogenic origin. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2012;56(3):305–9.

Okamoto Y, Minami M, Tohno E, Anno I, Kunimatshu A, Ueda T. Multifocal peripheral nerve involvement associated with multiple myeloma. Skelet Radiol. 2007;36(12):1191–3.

Misdraji J, Ino Y, Louis DN, Rosenberg AE, Chiocca EA, Harris NL. Primary lymphoma of peripheral nerve: report of four cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(9):1257–65.

Kanda T. Biology of the blood–nerve barrier and its alteration in immune mediated neuropathies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(2):208–12.

Franco CD. Connective tissues associated with peripheral nerves. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;37(4):363–5.

Kim J, Kim YS, Lee EJ, Kang CS, Shim SI. Primary CD56-positive NK/T-cell lymphoma of median nerve: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 1998;13(3):331–3.

Stuart JE, Smith AC. Plasmacytoma of the superficial radial nerve. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2001;26(4):776–80.

Acknowledgments

S.C. is supported by European Regional Development Fund - Project FNUSA-ICRC (No. CZ.1.05/1.1.00/02.0123). We thank Dr. Brian P. O’Neill for the wisdom he shared with us during numerous consultations.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Declaration

An approval from the institutional review board was obtained before the conduct of the study. The patients have consented to the inclusion in the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2009.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Capek, S., Hébert-Blouin, MN., Puffer, R.C. et al. Tumefactive appearance of peripheral nerve involvement in hematologic malignancies: a new imaging association. Skeletal Radiol 44, 1001–1009 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-015-2151-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-015-2151-3