Abstract

Background

Pediatric imaging use and payment trends in accountable care organizations (ACOs) are seldom studied but are important for health policy decisions and resource allocation.

Objective

To evaluate patterns of advanced imaging use and associated payments over a 7-year period at a large ACO in the USA serving a Medicaid population.

Materials and methods

We reviewed paid claims data from 2011 through 2017 from an ACO, analyzing the MRI, CT and US use trends and payments from emergency department (ED) and outpatient encounters. We defined “utilization rate” as the number of advanced imaging procedures per 100 enrolled children per calendar year. Average yearly utilization and payments trends were analyzed using Pearson correlation.

Results

Across 7 years, 186,552 advanced imaging procedures were performed. The average overall utilization rate was 6.99 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 6.9–7.1). In the ED this was 2.7 (95% CI: 2.6–2.8) and in outpatients 4.3 (95% CI: 4.2–4.3). The overall utilization rate grew by 0.7% yearly (P=0.077), with US growing the most at 4.0% annually (P=0.0005), especially in the ED in the US, where it grew 10.8% annually (P=0.000019). The overall payments were stable from 2011 to 2017, with outpatient MRI seeing the largest payment decrease at 1.8% (P=0.24) and ED US showing the most growth at 3.3% (P=0.00016). Head CT and abdominal US were the two most common procedures.

Conclusion

Over the study period, advanced imaging utilization at this large pediatric ACO serving the Medicaid population increased, especially with US use in the ED. Overall payments related to advanced imaging remained stable over this period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The United States spends substantially more on health care than other high-income countries. In addition to administrative costs and higher prices, use of advanced imaging has been described as one of the factors that contribute to higher U.S. health care costs [1, 2]. When comparing the United States and 10 other high-income countries, the States performed the second highest number of imaging exams and had the second highest MRI and CT technology utilization rates [1]. A study also demonstrated higher rates of low-value imaging use in pediatric emergency departments in the United States vs. Canada.

Accountable care organizations (ACOs) comprise a relatively new organizational model under Medicare to work with payors and providers to deliver coordinated, high-quality care [3, 4]. In contrast to the adult ACOs, pediatric ACOs typically cover patients from lower-income families through Medicaid [4]. Pediatric imaging utilization reports in the literature are mostly limited to its use and often involve a hospital setting, specific indication or imaging modality, with few studies examining use and cost trends from a payor perspective [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

The aim of this study was to evaluate trends of advanced imaging utilization and associated payments in emergency department (ED) and outpatient settings over a 7-year period at a large pediatric ACO in the United States.

Materials and methods

Data source

Partners For Kids is a large pediatric ACO that manages fully capitated risk contracts with five Medicaid managed care plans for about 340,000 children (in 2017) enrolled across 34 counties in Ohio within both urban and rural communities. In this retrospective study approved by the institutional review board, we acquired 7 years of advanced imaging paid claims data from Partners For Kids from January 2011 through December 2017. Children and adults younger than 21 years were included. Paid claims data from the ACO were obtained using advanced imaging Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for MRI, CT, US and nuclear medicine studies. We excluded CPT codes with fewer than 25 total procedures performed in 2017 and 2018 combined. Eighty-three advanced imaging CPT codes were ultimately used to obtain paid claims data. Data were obtained for imaging-related encounters in the outpatient setting and the emergency department. We did not analyze inpatient settings because of the lack of access to reliable data from the ACO. We also obtained the encounter date and the paid claim amount for the imaging procedures.

Advanced imaging use analysis

We studied use of advanced imaging in both outpatient and ED settings for the 83 identified CPT codes, using the total ACO membership enrollment per year to calculate a utilization rate. We defined “utilization rate” as the ratio of advanced imaging procedures to the number of people enrolled multiplied by 100, providing the number of advanced imaging procedures performed for every 100 enrolled patients. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for overall utilization rate and also reported the utilization rate by modality and by encounter setting. Further, we calculated the annual percentage change in utilization rate over 7 years by modality and setting. Pearson correlation (r) and P-value (from Pearson r) were used to study the variation (yearly change) in utilization rate over the 7 years. A P-value of <0.05 denotes a statistically significant correlation coefficient. Utilization rate and annual percentage change in utilization rate were also calculated for four age groups. The four age groups were <1 year, 1–4 years, 5–12 years and ≥13 years.

Payment analysis

We defined “payments” as the actual amount paid by the ACO for each imaging-related claim. This reflects costs to the payor. To protect proprietary ACO data, for each year from 2011 to 2017, the annual payments were normalized to payments for the outpatient setting for the year 2011. For example, the normalized payment for outpatient MRI for 2011 was set to be 1 and MRI payments for ED and outpatient settings for all years were reported and compared to the normalized MRI outpatient payment for 2011. We calculated payment trends as percentage change per year by modality and setting. Similar to utilization rates, payment trends across the 7 years were analyzed using Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and P-values. A P-value of <0.05 denotes a statistically significant correlation coefficient.

Results

There was a total of 186,552 advanced imaging procedures on 107,963 unique patients.

Overall utilization

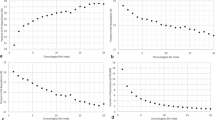

The overall utilization rate was 6.99 advanced imaging procedures per 100 enrolled patients per year on average (Table 1). It was 1.18 for MRI, 3.08 for US and 2.73 for CT. The overall ED utilization rate was 2.71 and overall outpatient utilization rate was 4.27. In the outpatient setting, the utilization rate was 1.15 for MRI, 2.27 for US and 0.78 for CT. Overall advanced imaging utilization rate grew by 0.7% yearly on average (P=0.077) from 2011 to 2017 (Fig. 1; Table 1). From 2011 to 2017, overall advanced imaging utilization rate in the ED showed an increase from 2.57 to 2.85 (r=0.91, P=0.004). Overall CT utilization showed the largest annual decrease of 2.1% (r = −0.9, P=0.0062). Nuclear medicine encounters were less frequent, with 44 unique ED and 2,981 unique outpatient encounters across the 7-year study period.

Graphs show utilization rates for all modalities combined (a), and for MRI (b), CT (c) and US (d). Average utilization rate for all modalities for 7 years was 6.99. Utilization rate changes are relatively stable across the years, with significant growth seen in both emergency department (ED) and outpatient (OP) US. Utilization rate is defined as number of imaging procedures for every 100 enrolled patients.

Utilization in the outpatient and emergency department settings

Utilization rate in the outpatient setting was stable across the 7 years, changing from 4.28 to 4.29 (r=0.19, P=0.69). In the ED, average utilization rate was 0.03 for MRI, 0.81 for US and 1.95 for CT. Ultrasound utilization rate grew the most at 4.0% annually (r=0.96, P=0.00047), especially in the ED, where it grew 10.8% annually (r=0.99, P=0.00002) but also in the outpatient setting, where it grew 2.1% annually (r=0.91, P=0.004). CT utilization rate in the ED was stable with an annual decrease of 0.7% (r = −0.64, P=0.12) but demonstrated a high average annual decline in the outpatient setting of 5.1% (r = −0.93, P=0.002). Table 1 lists the average annual utilization rate by modality and setting and percentage average yearly change by modality and setting.

Utilization by age

Across the 7 years, children younger than 1 year received a total of 18,331 advanced imaging studies (3,621 ED procedures in 3,422 unique children and 14,710 outpatient procedures in 11,310 unique patients). An average of 21,194 patients were enrolled each year. Children ages 1–4 years received a total of 21,861 procedures (7,526 ED procedures in 6,858 unique children and 14,335 outpatient procedures in 10,181 unique children). An average of 89,968 patients were enrolled each year. Children ages 5–12 years received 49,106 procedures (19,308 ED procedures in 16,316 unique children and 29,798 outpatient procedures in 21,224 unique children). An average of 155,701 patients were enrolled each year. Patients ages 13–18 years received 96,820 procedures (41,708 ED procedures in 29,480 unique patients and 55,112 outpatient procedures in 34,003 unique patients). An average of 106,332 patients were enrolled each year. Additionally, 434 procedures were performed on young adults ages 19–20 years (227 ED and 207 outpatient procedures).

Utilization rate for all imaging modalities was 12.2 for children younger than 1 year, 3.4 for children ages 1–4 years, 4.4 for children in the 5- to 12-year age group and 12.8 for those in the ≥13-years age group. Looking at age-wise changes (Table 2), a higher utilization rate for children <1 year and >13 years was seen across all imaging modalities when compared to those in the 1–4 and 5–12 age groups. Outpatient US for the <1-year age group had the highest utilization rate (7.75) of any modality in the ED or outpatient settings, followed by ED CT for patients in the ≥13-years age group (4.17) (Fig. 2; Table 2). For every age group, CT was the most used imaging modality in the ED setting, while US was the most used modality in the outpatient setting. CT was the least used modality in the outpatient setting for every age group.

Graph shows imaging utilization rates for different imaging modalities according to age groups. Outpatient (OP) US for children in the <1-year age group has the highest utilization rate (7.75) of any modality in the emergency department (ED) or outpatient setting, followed by ED CT for those in the ≥13-years age group (utilization rate 4.17)

Payment analysis

The overall normalized payments remained relatively unchanged from 2011 to 2017, with an annual average decrease of 0.49% (r = −0.57, P=0.18) (Fig. 3; Table 3). US had the highest overall average annual increase of 2.1% (r=0.94, P=0.002) followed by CT at 1.7% (r=0.96, P=0.0006). MRI exhibited an annual average decrease of −1.8% (r = −0.51, P=0.24). Examining payments by setting, ED US had the highest payment increase at 3.3% (r=0.98, P=0.0002), while the highest decline was seen in outpatient MRI at −1.8% (r = −0.53, P=0.22).

Most common procedures

The top 10 Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) procedures encountered in combined outpatient and ED settings over the 7-year study period are listed in Table 4, along with the top 5 procedures encountered in the separated ED and outpatient settings. There was a normalized annual increase of 0.71% (r=0.71, P=0.74) for the combined outpatient and ED settings. CT head without contrast agent was the most common imaging procedure (5,050 average yearly procedures). US and CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis comprised the remainder of the top 5. MRI of the brain without contrast agent was the only MRI procedure in the top 10. Overall, abdomen US demonstrated the largest average annual percentage gain at 8.2% (r=0.98, P=0.0001), while head CT demonstrated the largest average annual decline at 3.5% (r = −0.95, P=0.001).

Regarding ED encounters, there was a positive annual growth of 1.8% (r=0.91, P=0.004), with US of the abdomen demonstrating an annual increase of 18.8% (r=0.99, P=0.00002). In the ED setting, utilization of CT of the head/brain without contrast agent declined by 2.6% (r = −0.98, P=0.0001) and CT of abdomen without contrast agent declined by 1.7% (r = −0.24, P=0.6).

Outpatient encounters showed a minimal annual increase of 0.04% (r=0.19, P=0.68), with US of abdomen exhibiting annual growth of 5.8% (r=0.87, P=0.011). MRI of the brain without contrast agent exhibited a yearly decline of 2.9% (r = −0.95, P=0.001).

Discussion

Only a few studies have examined advanced imaging utilization and payment trends in a large pediatric ACO [15, 17]. There was a gradual increase in advanced imaging utilization but stable payments over the 7-year period. This is particularly notable in an era of growth in health care expenses. This supports previous findings that advanced imaging utilization alone is not the cause of high health care spending [1].

Ultrasound was the fastest growing modality over the 7 years of observation, with an average yearly growth of 18.8% for ED abdominal US procedures. This could, at least in part, reflect the increasing use of US for acute abdominal and pelvic pain in children and young adults instead of CT, especially for assessing right lower quadrant pain and acute appendicitis. Another contributing factor might be shift of some care from primary care to the ED. This trend toward increasing US use might continue in future years as physicians outside of radiology use US as a diagnostic and procedural adjunct for trauma, soft-tissue evaluation and visceral assessment [17].

Computed tomography of the brain without contrast agent is the most common advanced imaging procedure in our study, similar to other published results in population settings [13, 14, 18]. An important finding in our study was a decrease in the use of CT of head/brain (−3.5%), which coincides with the expanding reach of the Image Gently campaign, which popularized appropriate use guidelines for CT for head trauma and headache. This might also be a result of the development and use of dedicated head injury algorithms in pediatric patients [19].

Payments as defined by actual paid claims by the ACO were stable across imaging modalities over 7 years, with the largest average increase of 3.3% (yearly) seen only for ED US utilization. There was a negligible increase in outpatient imaging payments, with a non-statistically significant decrease in MRI utilization. While trying to understand cost trends for pediatric imaging, there is a lack of studies examining cost variations, especially in a Medicaid population. Our study is one of the first to examine payment trends in advanced imaging in pediatrics, especially at an ACO focusing on the Medicaid population. Payments in our pediatric Medicaid population did not keep up with the overall rate of medical inflation. The cost savings to the payor might come with trade-offs to patients; for example, previous studies have shown that lower Medicaid payments might be associated with reduced access to care [20].

While no other studies looked at imaging costs in a pediatric ACO setting, some studies have looked at imaging utilization in children over time. Tompane et al. [21] looked at diagnostic imaging procedures from 2001 to 2009. In their study of 63,000 patients at a single tertiary-care hospital, the utilization rate for CT and US was similar to our reported results, while our MRI rate was lower (1.7 vs. 1.2). Their study included inpatient imaging, as well, which was not included in our study. Their utilization rate was normalized to all patients who visited their hospital but did not include the community-based enrollment data that were used in our study. The study by Tompane et al. reported on a smaller number of advanced diagnostic imaging studies than our study (41,444 vs. 186,552). Our study looked at advanced imaging utilization in an ACO, which captured all imaging use in a defined population and not just procedures at one medical center. Our study also examined use of advanced imaging by age groups, showing increases for patients <1 year and ≥13 years of age when compared to those 1–4 years and 5–12 years of age. This increase was consistent across all imaging modalities.

Another study, by Smith-Bindman et al. [14], looked at advanced imaging utilization in the United States in both adults and children in the inpatient, outpatient and ED settings at seven major health maintenance organizations and preferred provider organizations. The utilization rate of CT in children and young adults was higher in our study (2.7 vs. 2.2), while our MRI and US rates were lower (MRI: 1.2 vs. 2.1; US: 3.1 vs. 5.9). Smith-Bindman et al. [14] also demonstrated no significant increase in CT and MRI utilization between 2012 and 2016, and a 2.4% annual increase in US procedures, trends that were similar to our findings. The longer 8-year duration of the Smith-Bindman study might be a better representative of modality-specific growth rates, which were not uniform over the period, likely because of variable adoption of new and evolving practice patterns by the broad spectrum of institutions that participated in our ACO.

Our study has several limitations. It is limited to imaging utilization at a single ACO, albeit a large one. The study focused on an exclusively Medicaid population, which might not represent the utilization patterns in a commercially insured population. Next, our study did not analyze inpatient imaging utilization and payment because of a lack of access to reliable inpatient data from the ACO. Payments were defined as actual claims paid by the ACO. This reflects costs to the payor but not to the entire health care system. The claims data also did not allow for examination of other factors such as chargemaster or CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) changes that might affect payments. Finally, we did not assess appropriateness of imaging or imaging quality, which are important considerations when determining the value of imaging.

Conclusion

By analyzing imaging utilization trends sorted by modality, patient care setting, and payments, this study provides important information for planning future resource allocation and examining the impact of imaging on health care costs over several years.

References

Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK (2018) Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA 319:1024–1039

Anderson GF, Reinhardt UE, Hussey PS, Petrosyan V (2003) It's the prices, stupid: why the United States is so different from other countries. Health Aff 22:89–105

Fisher ES, Shortell SM (2010) Accountable care organizations: accountable for what, to whom, and how. JAMA 304:1715–1716

Perrin JM, Zimmerman E, Hertz A et al (2017) Pediatric accountable care organizations: insight from early adopters. Pediatrics 139:e20161840

Arnold RW, Graham DA, Melvin PR, Taylor GA (2011) Variability in imaging utilization in U.S. pediatric hospitals. Pediatr Radiol 41:867–874

Barrick L, Cohen DM, Schober MS, Schwaderer A (2020) National imaging trends of recurrent pediatric urolithiasis. Pediatr Emerg Care 36:e217–e221

Edwards MJ, Jenkel T, Weller B et al (2020) Computed tomography scan utilization in pediatric trauma: impact on length of stay and incidence of false positive findings. Pediatr Emerg Care. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000002087

Kelleher KJ, Cooper J, Deans K et al (2015) Cost saving and quality of care in a pediatric accountable care organization. Pediatrics 135:e582–e589

Lodwick DL, Cooper JN, Kelleher KJ et al (2015) Variation in utilization of computed tomography imaging at tertiary pediatric hospitals. Pediatrics 136:e1212–e1219

Marin JR, Rodean J, Hall M et al (2020) Trends in use of advanced imaging in pediatric emergency departments, 2009-2018. JAMA Pediatr 174:e202209

Marin JR, Rodean J, Hall M et al (2021) Racial and ethnic differences in emergency department diagnostic imaging at U.S. children's hospitals, 2016-2019. JAMA Netw open 4:e2033710

Ohana O, Soffer S, Zimlichman E, Klang E (2018) Overuse of CT and MRI in paediatric emergency departments. Br J Radiol 91:20170434

Roudsari BS, Psoter KJ, Vavilala MS et al (2013) CT use in hospitalized pediatric trauma patients: 15-year trends in a level I pediatric and adult trauma center. Radiology 267:479–486

Smith-Bindman R, Kwan ML, Marlow EC et al (2019) Trends in use of medical imaging in U.S. health care systems and in Ontario, Canada, 2000-2016. JAMA 322:843–856

Uffman JC, Tumin D, Raman V et al (2017) MRI utilization and the associated use of sedation and anesthesia in a pediatric ACO. J Am Coll Radiol 14:924–930

Otero HJ, Crowder L (2017) Imaging utilization for the diagnosis of appendicitis in stand-alone children's hospitals in the United States: trends and costs. J Am Coll Radiol 14:603–608

Marin JR, Lewiss RE, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine et al (2015) Point-of-care ultrasonography by pediatric emergency medicine physicians. Pediatrics 135:e1113–e1122

Dorfman AL, Fazel R, Einstein AJ et al (2011) Use of medical imaging procedures with ionizing radiation in children: a population-based study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 165:458–464

Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS et al (2009) Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 374:1160–1170

Tang SS, Hudak ML, Cooley DM et al (2018) Increased Medicaid payment and participation by office-based primary care pediatricians. Pediatrics 141:e20172570

Tompane T, Bush R, Dansky T, Huang JS (2013) Diagnostic imaging studies performed in children over a nine-year period. Pediatrics 131:e45–e52

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krishnamurthy, R., Shah, S.H., Wang, L. et al. Advanced imaging use and payment trends in a large pediatric accountable care organization. Pediatr Radiol 52, 22–29 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-021-05198-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-021-05198-2