Abstract

Purpose

Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartomas (NCMH) are rare, predominantly benign tumors of the sinonasal tract. The distinction from higher grade malignancy may be challenging based on imaging features alone. To increase the awareness of this entity among radiologists, we present a multi-institutional case series of pediatric NCMH patients showing the varied imaging presentation.

Methods

Descriptive assessment of imaging appearances of the lesions on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. In addition, we reviewed demographic information, clinical data, results of genetic testing, management, and follow-up data.

Results

Our case series consisted of 10 patients, with a median age of 0.5 months. Intraorbital and intracranial extensions were both observed in two cases. Common CT findings included bony remodeling, calcifications, and bony erosions. MRI showed heterogeneous expansile lesion with predominantly hyperintense T2 signal and heterogenous post-contrast enhancement in the majority of cases. Most lesions exhibited increased diffusivity on diffusion weighted imaging and showed signal drop-out on susceptibility weighted images in the areas of calcifications. Genetic testing was conducted in 4 patients, revealing the presence of DICER1 pathogenic variant in three cases. Surgery was performed in all cases, with one recurrence in two cases and two recurrences in one case on follow-up.

Conclusion

NCMHs are predominantly benign tumors of the sinonasal tract, typically associated with DICER1 pathogenic variants and most commonly affecting pediatric population. They may mimic aggressive behavior on imaging; therefore, awareness of this pathology is important. MRI and CT have complementary roles in the diagnosis of this entity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartomas (NCMH) are rare and predominantly benign tumors of the sinonasal tract, most commonly affecting infants or young children [1]. Symptomatology is variable, with a visible mass and nasal obstruction being the most common clinical presentation [2]. NCMHs may appear as heterogeneous and locally destructive masses, and this makes the radiological distinction from malignancy challenging [1]. To date, most of the imaging literature on NCMHs is from single case reports. To increase the awareness of this entity among radiologists, we present a multi-institutional case series of pediatric NCMH patients showing the varied imaging presentation.

Methods

This retrospective, multi-center case series of pediatric NCMH patients was a result of collaboration between five institutions. Inclusion criterion was pathologically proven NCMH in a pediatric (< 19 years) patient. We performed a descriptive assessment of imaging appearances of the lesions on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We also reviewed demographic information, clinical data on presentation, results of genetic testing, management, and follow-up data.

Results

Our case series consisted of 10 patients (6 females) with pathologically proven NCMH (Fig. 1). CT imaging was available in 9 patients (7 with intravenous contrast) and post-contrast MRI was performed in 8 patients. Six patients had both CT and MRI data available.

Initial age at presentation ranged from 0 to 104 months (median 0.5 months; IQR 0–58.5 months). Five NCMHs were congenital. The most common clinical symptom was visible mass or facial deformity present in 7 patients. One child had exophthalmos and 2 children presented with respiratory difficulty.

On CT imaging, bony remodeling was present in eight patients, calcifications in seven patients, and bony erosions in six patients. MRI showed an expansile lesion in all cases with predominantly hyperintense signal on T2-weighted sequence in six cases and cystic appearing areas in three cases (Fig. 2). T1-weighted images showed predominantly intermediate signal in most patients (n = 6), with focal hyperintensities within the lesion in 1 patient.

Coronal CT (a) shows a lesion expanding the left nasal cavity. The lesion has a rings and arcs calcification pattern reminiscent of chondroid tissue (arrow). Note osseous re-modeling (arrowheads). On MRI, the lesion shows mixed T2 (b) and T1 signal (c), and heterogeneous post-contrast enhancement (d), with non-enhancing and T2 hyperintense cystic areas (arrows in b and d)

Diffusion MR imaging was performed in five patients and showed relatively high diffusivity with only a portion of one lesion demonstrating lower ADC values. SWI was performed in three cases and showed areas of signal drop out in all of them, corresponding to the presence of calcifications. Most tumors were centered on the nasal cavity (5 on the left and 4 on the right side, one was bilateral). One left-sided tumor also involved the nasopharynx. Intraorbital and intracranial extensions were both observed in two cases. Size of the tumors ranged from 10 × 8 mm to 62 × 21 mm in the axial plane. Additional CT and MRI images of selected patients including another patient with intracranial extension of the neoplasm are shown in Fig. 3.

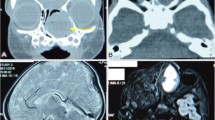

SWI (a) and ADC map (b) of a child with NCMH show low to intermediate ADC values (between 900 and 1200 mm.2/s) with no corresponding hypointensity on SWI to suggest hemorrhage or calcification in the dorsal part of the tumor (arrows in a and b). Imaging in another child showing extensive bony remodeling with calcifications on CT (c) with associated low to intermediate signal intensity on DWI (d). T2-weighted image (e), contrast enhanced T1-weighted image (f), DWI (g), and ADC map (h) of an infant show heterogeneous, predominantly T2 hypointense, heterogeneously enhancing lesion centered in the left nasal cavity with intracranial extension. There is intermediate to high diffusivity (which may in part be due to a non-enhancing cystic area).

Differential diagnoses that were reported on the initial imaging included NCMH (50%), teratoma (30%), sarcoma (30%), nasal glioma (10%), and hematoma (10%). Genetic testing was performed in 4/10 and among these, three cases were positive for a pathogenic DICER1 variant. Two cases with DICER1 pathogenic variants had a history of pulmonary pleuroblastoma and the third had a history of multiple malignancies (rhabdomyosarcoma, spindle cell sarcoma of the kidney, and papillary thyroid carcinoma). Surgery was performed in all cases, with one recurrence in two cases and two recurrences in one case on follow-up.

Discussion

NCMHs are composed of mature and immature hyaline cartilage, areas of calcification, spindle cells, and myxoid stromal tissue [1, 3]. Aggressive characteristics are usually absent on histology, although malignant transformation has been reported [4].

Typical presentation is in the first years of life [1], but cases have been reported in adults [3]. In our pediatric series, the commonest presentation was with nasal mass or facial deformity, which is concordant with previous publications [3]. Depending on the location, presentation may also be with respiratory or feeding difficulties, rhinorrhea, epistaxis or otitis media [3]. Orbital involvement is common, resulting in strabismus, hypertelorism, proptosis, enophthalmos or ophthalmoplegia [1]. Intracranial extension may also be encountered, resulting in hydrocephalus or oculomotor disturbances [3, 5].

In most cases, physical examination is sufficient for the initial diagnosis of the intranasal mass [3]. However, further characterization of the lesion and the evaluation of the adjacent structures with CT or MRI is usually required [5]. On CT, NCMHs display presence of calcification in ~ 70% and osseous remodeling in majority of cases. Bony erosion may be seen, most commonly involving the cribriform plate and the lamina papyracea [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19], although frank bony destruction is usually absent [3, 5]. Osseous changes are generally better appreciated on CT [19], but areas of mineralization within the cartilaginous matrix may also be suggested on MRI, specifically by hypointense T2 signal [19], or with the use of SWI. On the other hand, cystic and myxoid components are in general much better appreciated using MRI (Fig. 3). T2-weighted images most commonly show heterogeneous mass, with signal characteristics ranging from predominantly hyperintense in approximately 50% to predominantly hypointense in ~ 25% of cases [5,6,7,8,9, 11, 13, 14, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Most of NCMHs show intermediate to hypointense T1 signal [5, 7, 8, 10, 22, 23, 25], with heterogeneous contrast enhancement present in ~ 75% of cases [5, 7, 9, 13, 15, 19, 23, 24]. Of note, enhancement may only be peripheral in about 15% of cases [8, 25]. Most of the lesions show increased diffusivity; however, we do report a case with relatively low ADC values (Fig. 1). Importantly, intratumoral hemorrhage may also be the source of low ADC [8], and this may be addressed by utilizing SWI. On the other hand, extensive hypointensities on SWI due to calcifications were present in all three of our patients in whom SWI was performed. Non-enhancing cystic areas may be appreciated in about half of cases [5, 7, 8, 11, 14, 15, 19, 25]. In addition, MRI is also superior in evaluation of the intraorbital and intracranial extension of the disease [19].

In our series, initial imaging diagnoses included teratoma, sarcoma, nasal glioma, and hematoma. In pediatric population, inverted papilloma, giant cell reparative granuloma, chondro-osseous respiratory adenomatoid hamartoma, aneurysmal bone cyst, and rhabdomyosarcoma may also be considered. In addition, esthesioneuroblastoma and chondrosarcoma may present in a similar fashion, but are more common in adolescents and adults [3]. Rarely, the extensive cystic component of the tumor may even mimic encephalocele [25].

We confirmed DICER1 pathogenic variants in 3/4 tested patients, and all of them had history of previous malignancy. This is similar to the report from Stewart et al. who confirmed the mutation in 6/8 cases [26]. NCMH may therefore be considered a part of DICER1 familial tumor susceptibility syndrome, conferring the increased risk most commonly for pleuropulmonary blastoma, but also ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors, Sertoli–Leydig cell tumor, juvenile granulosa cell tumor and gynandroblastomas, and less commonly cystic nephroma, thyroid gland tumors, ciliary body medulloepithelioma, botryoid-type embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, renal sarcomas, pituitary blastomas, and pineoblastomas [1, 26].

Surgical removal is curative [26] and may be performed endoscopically in cases limited to nasal cavity [3]. However, local recurrences may occur in around 25% of cases [26].

Summary

NCMHs are predominantly benign tumors of the sinonasal tract, typically associated with DICER1 pathogenic variants and most commonly affecting pediatric population. They may mimic aggressive behavior on imaging; therefore, awareness of this pathology is important. MRI and CT have complementary roles in the diagnosis of this entity.

References

Mason KA, Navaratnam A, Theodorakopoulou E, Chokkalingam PG (2015) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma (NCMH): a systematic review of the literature with a new case report. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 44(1):28

Saunders TFC, Bruijnzeel H, Ahmed S, Paruleka M, McDermott AL (2022) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma: an update. J Laryngol Otol 136(12):1140–1147

Johnson C, Nagaraj U, Esguerra J, Wasdahl D, Wurzbach D (2007) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma: radiographic and histopathologic analysis of a rare pediatric tumor. Pediatr Radiol 37(1):101–104

Li Y, Yang QX, Tian XT, Li B, Li Z (2013) Malignant transformation of nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma in adult: a case report and review of the literature. Histol Histopathol 28(3):337–344

Kim JE, Kim HJ, Kim JH, Ko YH, Chung SK (2009) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma: CT and MR imaging findings. Korean J Radiol 10(4):416–419

Thirunavukkarasu B, Chatterjee D, Mohindra S, Dass Radotra B, Prashant SJ (2020) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma. Head Neck Pathol 14(4):1041–1045

Wang T, Li W, Wu X, Li Q, Cui Y, Chu C et al (2014) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma in young children: CT and MRI findings and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol 12:257

Kitayama T, Akaki S, Hisazumi K, Yoshio K, Inoue D, Tajiri N et al (2019) An adult case of nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma: imaging characteristics including diffusion-weighted images. Acta Med Okayama 73(6):529–532

Finitsis S, Giavroglou C, Potsi S, Constantinidis I, Mpaltatzidis A, Rachovitsas D et al (2009) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma in a child. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 32(3):593–597

Uzomefuna V, Glynn F, Russell J, McDermott M (2012) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma with no nasal symptoms. BMJ Case Rep. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.11.2011.5148

Silkiss RZ, Mudvari SS, Shetlar D (2007) Ophthalmologic presentation of nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma in an infant. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 23(3):243–244

Norman ES, Bergman S, Trupiano JK (2004) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol 7(5):517–520

Nakaya M, Yoshihara S, Yoshitomi A, Baba S (2017) Endoscopic endonasal excision of nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma with intracranial extension. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 134(6):423–425

Moon SH, Kim MM (2014) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma with incomitant esotropia in an infant: a case report. Can J Ophthalmol 49(1):e30–e32

Kim DW, Low W, Billman G, Wickersham J, Kearns D (1999) Chondroid hamartoma presenting as a neonatal nasal mass. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 47(3):253–259

Kato K, Ijiri R, Tanaka Y, Hara M, Sekido K (1999) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma of infancy: the first Japanese case report. Pathol Int 49(8):731–736

Behery RE, Bedrnicek J, Lazenby A, Nelson M, Grove J, Huang D et al (2012) Translocation t(12;17)(q24.1;q21) as the sole anomaly in a nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma arising in a patient with pleuropulmonary blastoma. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 15(3):249–53

Alrawi M, McDermott M, Orr D, Russell J (2003) Nasal chondromesynchymal hamartoma presenting in an adolescent. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 67(6):669–672

Yao-Lee A, Ryan M, Rajaram V (2011) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma: correlation of typical MR. CT and pathological findings Pediatr Radiol 41(5):675–677

Cicek MT, Bayindir T, Aslan M, Sigirci A, Gunduz E (2022) A rare cause of respiratory distress in newborn: huge nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma; patient Report. J Craniofac Surg 33(4):e411–e413

Avci H, Comoglu S, Ozturk E, Bilgic B, Kiyak OE (2016) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma: a rare nasal benign tumor. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg 26(5):300–303

Unal A, Kum RO, Avci Y, Unal DT (2016) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma, a rare pediatric tumor: Case report. Turk J Pediatr 58(2):208–211

Schaerer D, Nation J, Rennert RC, DeConde A, Levy ML (2021) Pediatric nasal chondromesenchymal tumors: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg 56(1):61–66

Lee CH, Park YH, Kim JY, Bae JH (2015) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma causing sleep-disordered breathing in an infant. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 8(8):9643–9646

Kim B, Park SH, Min HS, Rhee JS, Wang KC (2004) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartoma of infancy clinically mimicking meningoencephalocele. Pediatr Neurosurg 40(3):136–140

Stewart DR, Messinger Y, Williams GM, Yang J, Field A, Schultz KA et al (2014) Nasal chondromesenchymal hamartomas arise secondary to germline and somatic mutations of DICER1 in the pleuropulmonary blastoma tumor predisposition disorder. Hum Genet 133(11):1443–1450

Funding

No funding, grants, or other support was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interests/competing interests. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

Research ethics board approval was obtained from the participating hospitals. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Retrospective study approved by REB with consent waiver; no patient identifying information used.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Avsenik, J., Albalkhi, I., Prabhu, S.P. et al. Pediatric nasal chondromesenchymal hamartomas: a case series. Neuroradiology 66, 437–441 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-023-03276-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-023-03276-w