Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to describe the characteristics of older patients treated with psychotropic medicines and the associated factors and to assess their inappropriate use.

Methods

An observational, prospective study was carried out in 672 elderly patients admitted to seven hospitals for a year. A comparison of sociodemographic characteristics, geriatric variables, multimorbidity and the number of prescribed medicines taken in the preceding month before hospitalization between patients treated with psychotropics and those not treated was performed. To assess factors associated with psychotropics, multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed. Inappropriate use was assessed using the Beers and the STOPP criteria.

Results

A total of 57.5 % patients (median [Q1–Q3] age 81.7 [78.2–86.1], 65.7 % female) were treated with psychotropics (44.2 % anxiolytics, 22.6 % antidepressants and 10.8 % antipsychotics). Independent factors associated with the use of psychotropics were female gender (OR = 2.3; CI 95 %,1.6–3.5), some degree of disability on admission (slight [OR = 2.2; 1.2–4.2], moderate [OR = 3.2, 1.6–6.6], severe [OR = 3.4; 1.4–8] and very severe [OR = 5.1; 2.0–12.8]) and polypharmacy (5–9 medicines [OR = 3.0; 1.3–6.9] and ≥10 medicines [OR = 6.0; 2.7–13.6]). The associated factors varied depending on the different types of psychotropics. In patients treated with psychotropics, the percentage of those with at least one Beers (61.6 %) or at least one STOPP (71.4 %) criteria was significantly higher in comparison with those not treated with psychotropics (30.7 and 47.7 %, respectively, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Psychotropics are widely used in the elderly population and often their use is inappropriate. Female gender, a poor functional status and polypharmacy, are the characteristics linked to their use. Interventional strategies should be focused on patients with these characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

A high use of psychotropic medicines has been reported on especially in the elderly [1–9]. Additionally, a progressive increase in their use has been described in older people over the years [2, 6]. This high use is a matter of concern because their prescription has often been judged inappropriate [10–13]. Moreover, inappropriate use of medicines has an impact on hospitalizations, mortality and costs [14]. Particularly, inappropriate use of psychotropic medicines has been associated with a high incidence of side effects especially in the older population such as psychomotor and cognitive impairment, falls and fractures [15–17].

This high prescription of psychotropic medicines in older people has been described in those living in nursing homes [7, 8] and in elderly community-dwelling people as well [1, 3, 6, 9]. The figures for psychotropic medicine prescription have varied from 52 to 75 % for the elderly population living in nursing homes [7, 8]. The corresponding figures in the elderly community-dwelling people have ranged from 29 to 43.5 % [1, 6]. In addition, several factors are responsible for psychotropic medicine prescription in the elderly community-dwelling population [1, 6] and also in those living in nursing homes [7, 8].

Although patterns of psychotropic drugs have often been assessed in patients admitted to nursing homes and also in the community-dwelling patients, fewer studies have analysed the prevalence and the characteristics of patients treated with psychotropic medicines admitted to hospitals [13].

In the context of a multicentric study focused on inappropriate prescribing of medicines in the elderly (patients 75 years old and over) in the month prior to hospital admission [18], a sub-analysis of the use of psychotropic drugs was performed. The goals of this sub-analysis were to describe the characteristics of older patients treated with different classes of psychotropic medicines, and the associated factors, in order to typify the characteristics of elderly patients treated with these medicines and compared them to those not treated with psychotropic medicines. In addition, a secondary objective was to assess the inappropriate use of psychotropic medicines in this population and compare them to those not treated with psychotropic medicines. The initial hypothesis was that the use of psychotropic drugs in elderly patients is high, very often inappropriate and the profile of patients treated with these medicines differs between the different types of psychotropic drugs.

Methods

A prospective, multicentric study on a cohort of patients hospitalized in the Internal Medicine Services of seven Spanish hospitals was carried out for a year (from April 2011 to March 2012). The study methodology has been described in detail in previous papers [18, 19], and this is a study focusing on the use of psychotropic drugs in this population. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Clinical Investigation in each participating hospital. Signed informed consent was obtained from patients or caregivers in case of cognitive impairment.

Patients, 75 years or older, admitted with an acute illness or an exacerbation of a chronic condition were included. Hospital admission was through either the emergency department or directly from primary care. Patients with a scheduled or a short-duration (less than 24 h) admission, those seen as an outpatient by the researcher, and those where no access was available to primary care medical information were excluded from the study. Each hospital included two patients per week admitted with the inclusion criteria. Patients were selected randomly every week on consecutive days from the hospitalization lists using a random number generation program. By design, half of the included patients were 85 years or older [20].

Information on a patient’s characteristics and the prescribing medicines was obtained from the hospital and the primary care electronic medical records and from interviews with the patients and/or relatives, using a structured questionnaire. On admission, data about the patient’s age, gender and social characteristics such as residence (home, nursing home or another hospital), and frequency of health care services utilization (number of visits to general practitioner or hospital admissions) for 1 month prior to admission, was collected.

In addition, information on activities of daily living, basal (1 month previous to admission) and on admission (during the first 48 h), using the Barthel index [21], cognitive function using the Pffeifer scale [22], specific diagnosis and cumulative multimorbitity as quantified by the Charlson Co-morbidity index [23] and the polypathological patient scale [24], number of falls in the preceding 3 months and delirium during the first 48 h of admission using the Confusion Assessment Method [CAM] [25], was assessed. On discharge, data about where the patient went (home, nursing home or another hospital) and the Barthel index score were obtained.

Regarding medicine exposure, information on the number and type of prescription medicines in the preceding month before admission was obtained using a complete pharmacological anamnesis. Polypharmacy has been defined as the concomitant use of five or more drugs [26–28]. Medicines were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. Psychotropic drugs were categorized as follows: any psychotropic (ATC-codes N05A except lithium, N05B/N05C and N06A,), antipsychotics (N05A but lithium), anxiolytics or hypnotics-sedatives (N05B/N05C) and antidepressants (N06A).

For the purpose of this study, data on patients treated with any psychotropic medicine and with different kinds of psychotropic medicines were compared to those not treated with these medicines. To assess inappropriate prescribing in patients, the Beers 2002 [29] and STOPP [30] criteria were used. Beers-listed Potentially Inappropriate Medicines (PIM) were considered when at least one of the Beers criteria was prescribed, STOPP-listed PIM, when at least one STOPP criteria was prescribed. In addition, the Beers-listed PIM and STOPP-listed PIM criteria related to the central nervous system or to psychotropic medicines were analysed specifically (shown in the supplementary material).

Since the number of eligible patients was different in the participating centres, and the study design oversampled the proportion of older patients, analyses were weighted by frequency and age distribution of the eligible population in each hospital. Descriptive results for continuous and count variables are shown as median, first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles. Comparisons for continuous and count variables were made using regression analyses and for categorical ones using Rao-Scott Chi-square tests. To examine the association between psychotropic use of medicines and associated factors, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed where prescribing psychotropic medicines was the dependent variable and sociodemographic and geriatric variables, multimorbidity, number of prescription medicines in the preceding month before hospitalization were the independent variables. In addition, the same variables were used to examine the association between anxiolytics or hypnotic-sedatives, antidepressants and antipsychotics and potential risk factors. The adjusted odds ratio (OR) with its 95 % confidence intervals (CI) was calculated. Statistical significance was considered when the p value was ≤0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using the procedures for complex surveys of the SAS 9.2 program (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

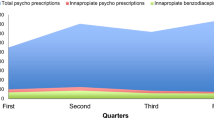

A total of 672 patients [median age (Q1–Q3) 82 (79–86) years, 55.9 % female] were included, and 57.5 % of them were treated with a psychotropic medicine (35.2 % were treated with one psychotropic drug, 15.8 % with two and 6.5 % with three or more psychotropic drugs).

The main clinical characteristics of patients treated with any psychotropic medicines are shown in Table 1. Median age (Q1–Q3) was 81.7 (78.2–86.1) years, and 65.7 % were female. Patients treated with any psychotropic medicine were more frequently women (p < 0.001), lived more often in nursing homes (p = 0.030), had more multimorbidity (p = 0.016), a worse functional status (p < 0.001) and poorer cognitive baseline function (p = 0.008). They were more often discharged to nursing home facilities and less often to their homes (p = 0.011). Polypharmacy was more often seen in patients treated with psychotropic drugs than those not treated (97.1 vs. 86.2 %, p < 0.001).

A total of 44.2 % of patients were treated with anxiolytics or hypnotics-sedatives (38.7 % of them with one medicine and 5.5 % with two or more), 22.6 % with antidepressants (19.4 % with one medicine and 3.2 % with two or more) and 10.8 % with antipsychotics (9.1 % with one medicine and 1.7 % with two or more). A total of 12.4 % were treated with a combination of anxiolytics or hypnotics-sedatives and antidepressants. The most frequently prescribed psychotropic medicines were anxiolytics or hypnotics-sedatives (lorazepam [17.4 %] and potassium clorazepate [7.2 %]), antidepressants (citalopram [6.6 %] and paroxetine [3.3 %]) and antipsychotics (haloperidol [4.7 %], risperidone [3.4 %] and quetiapine [2.3 %]). The characteristics of patients treated with anxiolytics or hypnotics-sedatives, antidepressants and antipsychotics in comparison with those not treated with these medicines are shown in Table 2.

In patients treated with any psychotropic medicine, the percentage of those with at least one PIM-listed Beers or at least one PIM-listed STOPP were significantly higher in comparison with those not treated with these medicines (p < 0.001) (Table 3). The percentage of PIM-listed Beers and PIM-listed STOPP criteria related to psychotropic medicines and central nervous system in patients treated with any psychotropic medicine were 33.0 and 11.3 %, respectively. In patients treated with anxiolytics or hypnotics-sedatives and in those treated with antidepressants the percentage of those with at least one PIM-listed Beers and with at least one PIM-listed STOPP were also higher in comparison with the percentages of those not treated with these medicines (Table 3). However, in those treated with the antipsychotics, no differences were found in the percentage of those with at least one PIM-listed Beers in comparison with those not treated with these medicines but the percentage of those with at least one-listed STOPP were higher in patients treated with antipsychotics in comparison with those not treated.

The use of long-acting benzodiazepines independent of diagnoses or conditions (19.7 %) and the use of short- to intermediate-acting benzodiazepine and tricyclic antidepressants in patients with previous falls or syncopes (17.3 %) were the most commonly found PIMs according to the Beers’ criteria. The most commonly encountered STOPP criteria were also the use of benzodiazepines in patients who are prone to falls (25.7 %) and the use of long-term long-acting benzodiazepines and benzodiazepines with long-acting metabolites (18.8 %) (shown in the supplementary material).

The results of the multivariate regression analysis are shown in Table 4. Only the statistically significant risk factors are presented. Independent factors associated with use of any psychotropic medicines were female gender, a poor functional status and polypharmacy. Among those treated with anxiolytics or hypnotic-sedative medicines, female gender, use of antidepressant medicines and polypharmacy were the associated independent factors. Female gender, use of anxiolytics or hypnotic-sedatives medicines, living in nursing home facilities and polypharmacy were factors associated with the use of antidepressant medicines. Finally, independent factors associated with the use of antipsychotics medicines were a poor functional status and delirium.

Discussion

Our study shows that there is a high prevalence of psychotropic medicine use, especially of anxiolytics or hypnotic-sedatives followed by antidepressants and with a lower frequency antipsychotic medicines, in elderly patients admitted to hospital. Moreover, use of these drugs is often inappropriate and in these patients inappropriate use of medicines, in general, is higher than in those not treated with psychotropic medicines. The characteristics of patients treated with psychotropic medicines differ from those not treated with these medicines. Several factors are associated with the use of any psychotropic medicines such as female gender, a poor functional status and polypharmacy. However, the associated factors vary according to the different kind of psychotropic medicines. The main contributions of our study are the description of the use of psychotropic medicines in elderly patients admitted to hospital and the analysis of factors associated with the different types of psychotropic medicines in comparison with those not treated with these medicines.

The high prevalence of psychotropic use in the elderly admitted to hospital has already been reported on in other studies. Gallagher et al. [31] and Barry et al. [32] described their use as the second most prescribed group of drugs in this population. In the study by Prudent et al. [13] and Barry et al. [32], psychotropic medicines were used in around 50 % of patients. In our study, this percentage was even slightly higher. This high prevalence of use in this population is a matter of concern because their use has been associated to an increase of risk of severe side effects such as delirium, falls and fractures [33]. In addition, it should be noted as a factor of more concern that their use was often inappropriate in our study as has also been mentioned in other studies [13, 31]. Several factors have been linked to the use of psychotropic drugs. In the study by Prudent et al., the presence of depressive syndrome, cognitive symptoms deterioration, living in an institution, polypharmacy and co-morbidity were the factors related to psychotropic prescribing. Although most of these factors were statistically significant in the univariate analysis in our study, only polypharmacy, poor functional status and female gender were associated to the prescription of psychotropic drugs in the multivariate analysis. These findings are important because they allow us to identify the profile of patients (old women with a poor functional status treated with multiple drugs) where interventional measures should be focused on in order to prevent the misuse of these drugs.

Anxiolytics or hypnotics-sedatives have been the most frequently prescribed psychotropic medicines and their use was inappropriate in most cases. Use of long-acting benzodiazepines and their use independent of their half-life in patients with antecedents of falls or syncope were identified as the most frequent inappropriate criteria according to the Beers and STOPP tools. The magnitude of this problem has become a health concern in most European countries. In Spain, use of benzodiazepines has been described as the highest (85.5 DDD per 1.000 persons/day) in comparison with other developed countries such as USA (82.9 DDD per 1.000 persons/day), France (76.0 DDD per 1.000 persons/day), Italy (52.4 DDD per 1.000 persons/day), UK (19.3 DDD per 1.000 persons/day) and Germany (18 DDD per 1.000 persons/day) [34]. Moreover, the prevalence rate of population attributable risk of hip fracture has been associated with benzodiazepine use. Thus, in Spain, the population attributable risk of hip fracture associated with its use was 8.2 % in comparison to that of Germany that was 1.8 % [34]. In our study, polypharmacy, concomitant use of antidepressants and female gender were the factors linked to the prescription of anxiolytics or hypnotics-sedatives and interventions to decrease their use should be implemented especially in patients with these characteristics. In fact, some local initiatives have already been carried out in order to reduce the extent of inappropriate benzodiazepine usage. Vicens et al. in a randomized clinical trial showed that a structured intervention with a written individualized stepped-dose reduction is effective in primary care in reducing benzodiazepine use [35]. Simple interventions based on standardized interviews led by nurses and general practitioners aimed at withdrawing patients from long-term benzodiazepine use are being developed [36]. The impact of these initiatives should be evaluated in clinical practice in the coming years.

In our study, use of antidepressant medicines has been similar to that reported on in previous studies [6, 13, 31]. Antidepressants were the second group of psychotropic medicines used, and their use was often inappropriate too. Although in other studies an underuse of antidepressants has been described in a significant proportion of patients with depression [11], the present study aimed at analysing overuse of these medicines. Their inappropriate use in patients with antecedents of falls or syncope or in those with chronic constipation, urinary disturbances, arrhythmias or glaucoma were the most frequent criteria according to the Beers and STOPP instruments. In our study, polypharmacy, concomitant use of anxiolytics or hypnotics-sedatives, female gender and living in nursing home facilities were the characteristics linked to the use of antidepressants. In addition, use of antidepressants and anxiolytics or hypnotics-sedatives was the most frequent combination. Prescription of several kinds of medicines with effects on the central nervous system is common in the elderly and increases the risk of some side effects such as cognitive impairment, falls and fractures [37].

More than 10 % of the patients were treated with an antipsychotic medicine. The patients’ characteristics differed considerably in comparison with those of patients treated with other kind of psychotropic medicines. Generally, these patients were older, lived and were discharged more often to nursing home facilities, had a worse functional status, more delirium at admission and a worse cognitive function. Nevertheless, only delirium and a worse functional status were the statistically significant factors linked to antipsychotic medicines use in the multivariate analysis. Their long-term use as hypnotics (linked to risk of confusion, hypotension, extra-pyramidal side effects, gait dyspraxia and falls) and in patients with parkinsonism (likely to worsen extra-pyramidal symptoms) were the most frequent inappropriate criteria according to the STOPP tool. It is noteworthy that the mortality of these patients during admission was double that of patients not treated with antipsychotics. These data are consistent with the increase in mortality reported on in other studies [38, 39]. The use of antipsychotics in elderly patients has been broadly discussed because of their safety concerns [40], especially in older patients with dementia, and the increased risks of stroke and sudden death [38, 41]. In spite of these concerns, their use is still high especially in older people with conditions such as dementia, non-psychotic depression, anxiety and sleep disorders [42, 43].

Our results showed an inappropriate use of medicines in patients treated with psychotropics, as has already been described in other studies [13]. However, a relevant finding was that inappropriate use of medicines in these patients was higher in comparison with those not treated with psychotropic medicines. Moreover, depending on the tool and the class of the psychotropic medicine, inappropriate use of medicines in these patients was higher even when the criteria related to the use of psychotropic medicines were excluded. These findings suggest that patients’ characteristics result in a higher inappropriate use of medicines in this elderly population. In the study by Prudent et al., polypharmacy was associated with inappropriate use in the population [13]. Therefore, in these patients, to review the appropriateness of medicine use is crucial especially in those with polypharmacy. In line with this, some studies have already showed a beneficial impact of cessation of psychotropic drugs on falls and cognitive status [44]. Additional interventional strategies aimed at avoiding inappropriate use of psychotropic medicines and improving health care in the elderly are warranted.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, this is a subanalysis of a previous study aimed at analysing use of medicines in elderly population admitted to hospital, but this has probably not affected the results of the study. Secondly, the Beers’ criteria version 2002 was used, and currently, there are new versions [45, 46] which appeared once the study was initiated. A new version of the STOPP/START criteria has also been published very recently [47]. Thirdly, only patients admitted to medical units in hospitals were included and they are not representative of the very elderly community dwelling patients. Fourthly, there is not a universally accepted definition of polypharmacy, and different numbers of drugs have been used as a cut-off to define it. However, in our study, a cut-off point of five or more medicines was used because it is one of the definitions most frequently used. Finally, the consequences of inappropriate prescribing were not analysed. Our study also has some strengths. Firstly, it was carried out on a large group of very elderly people treated with psychotropic medicines in which few studies are available. Secondly, it was a multicentric study involving several hospitals lasting a year, and thirdly, an accurate methodology in both the geriatric and the pharmacological assessment of patients was applied.

In conclusion, psychotropic medicines are extensively used, and often inappropriately, in elderly patients admitted to hospital, despite the propensity of this population to develop side effects. Anxiolytics or hypnotic-sedatives are the most frequently used, followed by antidepressants and with a lower frequency, antipsychotic medicines. In these patients, inappropriate use of medicines, in general, is higher than in those not treated with psychotropic medicines even when specific criteria linked to psychotropic medicines are excluded. Factors associated with the use of any psychotropic medicines are female gender, a poor functional status and polypharmacy, although they vary depending on the studied kind of psychotropic medicines. The identification of these patients’ characteristics allows us to focus the interventional strategies on them in order to avoid inappropriate use and improve health care in this population.

PIPOPS investigators

Coordinator group: Antonio San-José (main investigator), Antònia Agustí, Xavier Vidal, Cristina Aguilera, Elena Ballarín, Eulàlia Pérez, Xavier Barroso.

Hospital Universitari Vall D’hebron (Barcelona): José Barbé, Carmen Pérez Bocanegra, Ainhoa Toscano, Carme Pal, Teresa Teixidor.

Hospital San Juan de Dios de Aljarafe (Sevilla): Antonio Fernández-Moyano, Mercedes Gómez Hernández, Rafael de la Rosa Morales, María Nicolás Benticuaga Martínez.

Hospital Clínic (Barcelona): Alfonso López-Soto, Xavier Bosch, Mª José Palau, Joana Rovira, Margarita Navarro.

Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge (Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona): Francesc Formiga, David Chivite, Beatriz Rosón, Antonio Vallano, Carme Cabot.

Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez (Huelva): Juana García, Isabel Ballesteros.

Hospital Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona): Olga H. Torres, Domingo Ruiz, Miquel Turbau, Paola Ponte, Gabriel Ortiz.

Hospital Universitario Virgen Del Rocío (Sevilla): Nieves Ramírez-Duque, Paula-Carlota Rivas Cobas, Paloma Gil

References

Schäfers A, Martini N, Moyes S, Hayman K, Zolezzi M, McLean C, Kerse N (2014) Medication use in community-dwelling older people: pharmacoepidemiology of psychotropic utilisation. J Prim Health Care 6:269–278

Ndukwe HC, Tordoff JM, Wang T, Nishtala PS (2014) Psychotropic medicine utilization in older people in New Zealand from 2005 to 2013. Drugs Aging 31:755–768

Harvey M, Currie D, Furman A, Mambourg S (2014) Measuring use of psychotropic drugs in veterans Affairs community living centers. Consult Pharm 29:588–601

Calvó-Perxas L, Turró-Garriga O, Aguirregomozcorta M, Bisbe J, Hernández E, López-Pousa S, Manzano A, Palacios M, Pericot-Nierga I, Perkal H, Ramió L, Vilalta-Franch J, Garre-Olmo J, Registry of Dementias of Girona Study Group (ReDeGi Study Group) (2014) Psychotropic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease: a longitudinal study by the Registry of Dementias of Girona (ReDeGi) in Catalonia, Spain. J Am Med Dir Assoc 15:497–503

Maust DT, Oslin DW, Marcus SC (2014) Effect of age on the profile of psychotropic users: results from the 2010 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 62:358–364

Carrasco-Garrido P, López de Andrés A, Hernández Barrera V, Jiménez-Trujillo I, Jiménez-García R (2013) National trends (2003-2009) and factors related to psychotropic medication use in community-dwelling elderly population. Int Psychogeriatr 25:328–338

Rolland Y, Andrieu S, Crochard A, Goni S, Hein C, Vellas B (2012) Psychotropic drug consumption at admission and discharge of nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 13:407.e7–407.12

Richter T, Mann E, Meyer G, Haastert B, Köpke S (2012) Prevalence of psychotropic medication use among German and Austrian nursing home residents: a comparison of 3 cohorts. J Am Med Dir Assoc 13:187.e7–187.e13

Rikala M, Korhonen MJ, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S (2011) Psychotropic drug use in community-dwelling elderly people-characteristics of persistent and incident users. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 67:731–739

Stevenson DG, Decker SL, Dwyer LL, Huskamp HA, Grabowski DC, Metzger ED, Mitchell SL (2010) Antipsychotic and benzodiazepine use among nursing home residents: findings from the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 18:1078–1092

Hanlon JT, Wang X, Castle NG, Stone RA, Handler SM, Semla TP, Pugh MJ, Berlowitz DR, Dysken MW (2011) Potential underuse, overuse, and inappropriate use of antidepressants in older veteran nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 59:1412–1420

Lesén E, Petzold M, Andersson K, Carlsten A (2009) To what extent does the indicator “concurrent use of three or more psychotropic drugs” capture use of potentially inappropriate psychotropics among the elderly? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 65:635–642

Prudent M, Dramé M, Jolly D, Trenque T, Parjoie R, Mahmoudi R, Lang PO, Somme D, Boyer F, Lanièce I, Gauvain JB, Blanchard F, Novella JL (2008) Potentially inappropriate use of psychotropic medications in hospitalized elderly patients in France: cross-sectional analysis of the prospective, multicentre SAFEs cohort. Drugs Aging 25:933–946

Sköldunger A, Fastbom J, Wimo A, Fratiglioni L, Johnell K (2015) Impact of inappropriate drug use on hospitalizations, mortality, and costs in older persons and persons with dementia: findings from the SNAC Study. Drugs Aging 32:671–678

Fraser LA, Liu K, Naylor KL, Hwang YJ, Dixon SN, Shariff SZ, Garg AX (2015) Falls and fractures with atypical antipsychotic medication use: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 175:450–452

Payne RA, Abel GA, Simpson CR, Maxwell SR (2013) Association between prescribing of cardiovascular and psychotropic medications and hospital admission for falls or fractures. Drugs Aging 30:247–254

Pratt NL, Ramsay EN, Kalisch Ellett LM, Nguyen TA, Barratt JD, Roughead EE (2014) Association between use of multiple psychoactive medicines and hospitalization for falls: retrospective analysis of a large healthcare claim database. Drug Saf 37:529–535

San-José A, Agustí A, Vidal X, Barbé J, Torres OH, Ramírez-Duque N, García J, Fernández-Moyano A, López-Soto A, Formiga F, Potentially Inappropriate Prescribing in Older Patients in Spain (PIPOPS) Investigators’ Project (2014) An inter-rater reliability study of the prescribing indicated medications quality indicators of the Assessing Care Of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) 3 criteria as a potentially inappropriate prescribing tool. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 58:460–464

San-José A, Agustí A, Vidal X, Formiga F, López-Soto A, Fernández-Moyano A, García J, Ramírez-Duque N, Torres OH, Barbé J, Potentially Inappropriate Prescription in Older Patients in Spain (PIPOPS) Investigators’ Project (2014) Inappropriate prescribing to older patients admitted to hospital: a comparison of different tools of misprescribing and underprescribing. Eur J Intern Med 25:710–716

San-José A, Agustí A, Vidal X, Formiga F, Gómez-Hernández M, García J, López-Soto A, Ramírez-Duque N, Torres OH, Barbé J, Potentially Inappropriate Prescription in Older Patients in Spain (PIPOPS) Investigators’ Project (2015) Inappropriate prescribing to the oldest old patients admitted to hospital: prevalence, most frequently used medicines, and associated factors. BMC Geriatr 15:42

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW (1965) Functional evaluation: The Barthel Index. A simple index of independence useful in scoring improvement in the rehabilitation of the chronically ill. Md State Med J 14:61–65

Pfeiffer E (1975) A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 23:433–441

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, Mackenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383

Bernabeu-Wittel M, Ollero-Baturone M, Moreno-Gaviño L, Barón-Franco B, Fuertes A, Murcia-Zaragoza J, Ramos-Cantos C, Alemán A, Fernández-Moyano A (2011) Development of a new predictive model for polypathological patients. The Profund Index. Eur J Intern Med 22:311–317

Inouye SK, Van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI (1990) Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med 113:941–948

Bjerrum L, Søgaard J, Hallas J, Kragstrup J (1998) Polypharmacy: correlations with sex, age and drug regimen. A Prescription Database Study Eur J Clin Pharmacol 54:197–202

Linjakumpu T, Hartikainen S, Klaukka T, Veijola J, Kivela SL, Isoaho R (2002) Use of medications and polypharmacy are increasing among the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol 55:809–817

Junius-Walker U, Theile G, Hummers-Pradier E (2007) Prevalence and predictors of polypharmacy among older primary care patients in Germany. Fam Pract 24:14–19

Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH (2003) Updating the Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med 163:2716–2724

Gallagher PF, O’Mahony D (2008) STOPP (screening tool of older persons’ potentially inappropriate prescriptions): application to acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with Beers Criteria. Age Ageing 37:673–679

Gallagher PF, Barry PJ, Ryan C, Hartigan I, O’Mahony D (2008) Inappropriate prescribing in an acutely ill population of elderly patients as determined by Beers’ Criteria. Age Ageing 37:96–101

Barry PJ, O’Keefe N, O’Connor KA, O’Mahony D (2006) Inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: a comparison of the Beers criteria and the improved prescribing in the elderly tool (IPET) in acutely ill elderly hospitalized patients. J Clin Pharm Ther 31:617–626

Lawlor DA, Patel R, Ebrahim S (2003) Association between falls in elderly women and chronic diseases and drug use: cross sectional study. BMJ 327:712–717

Khong TP, de Vries F, Goldenberg JS, Klungel OH, Robinson NJ, Ibáñez L, Petri H (2012) Potential impact of benzodiazepine use on the rate of hip fractures in five large European countries and the United States. Calcif Tissue Int 91:24–31

Vicens C, Bejarano F, Sempere E, Mateu C, Fiol F, Socias I, Aragonès E, Palop V, Beltran JL, Piñol JL, Lera G, Folch S, Mengual M, Basora J, Esteva M, Llobera J, Roca M, Gili M, Leiva A (2014) Comparative efficacy of two interventions to discontinue long-term benzodiazepine use: cluster randomised controlled trial in primary care. Br J Psychiatry 204:471–479

Lopez-Peig C, Mundet X, Casabella B, del Val JL, Lacasta D, Diogene E (2012) Analysis of benzodiazepine withdrawal program managed by primary care nurse in Spain. BMC Research Notes 5:684

Ensrud KE, Blackwell TL, Mangione CM, Bowman PJ, Whooley MA, Bauer DC, Schwartz AY, Hanlon JT, Nevitt MC, Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group (2002) Central nervous system-active medications and risk for falls in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc 50:1629–1637

Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM (2009) Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med 360:225–235

Maust DT, Kim HM, Seyfried LS, Chiang C, Kavanagh J, Schneider LS, Kales HC (2015) Antipsychotics, other psychotropics, and the risk of death in patients with dementia: number needed to harm. JAMA Psychiatry 72:438–445

Gareri P, Segura-García C, Manfredi VG, Bruni A, Ciambrone P, Cerminara G, De Sarro G, De Fazio P (2014) Use of atypical antipsychotics in the elderly: a clinical review. Clin Interv Aging 9:1363–1373

Shin JY, Choi NK, Jung SY, Lee J, Kwon JS, Park BJ (2013) Risk of ischemic stroke with the use of risperidone, quetiapine and olanzapine in elderly patients: a population-based, case-crossover study. J Psychopharmacol 27:638–644

Pérez J, Marín N, Vallano A, Castells X, Capellà D (2005) Consumption and cost of antipsychotic drugs. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 33:110–116

Marston L, Nazareth I, Petersen I, Walters K, Osborn DP (2014) Prescribing of antipsychotics in UK primary care: a cohort study. BMJ Open 4:e006135

van der Cammen TJ, Rajkumar C, Onder G, Sterke CS, Petrovic M (2014) Drug cessation in complex older adults: time for action. Age Ageing 43:20–25

American Geriatrics Society (2012) Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel (2012) American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 60:616–631

American Geriatrics Society (2015) Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel (2015) American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 63:2227–2246

O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P (2015) STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing 44:213–218

Acknowledgments

The project was financed by Grant no. EC10-211 obtained in a request for aid for the promotion of independent clinical research (SAS/2370/2010 Order of 27 September from the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Affairs and Equality).

Authors’ contributions

ASJ and AA, as directors and project leaders, had devised and wrote the proposal for obtaining the grant. XV, AA and AV wrote the manuscript and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. ASJ, AA, XV, FF, ALS, AFM, JG, NRD, OHT and JB contributed to the study design, coordinated data collection in each hospital, interpreted the data, reviewed the manuscript, provided comments and approved the final text of the manuscript. XV conducted statistical analysis. EB and EP controlled and monitorized quality data. XB designed the database. CA, CP, AT, CP, TT, DCh, BR, AV, CC, IB, DR, MT, PP, GO, PCRC, PG, MGH, RRM, MNB, XB, MJP, JR and MN collected the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vidal, X., Agustí, A., Vallano, A. et al. Elderly patients treated with psychotropic medicines admitted to hospital: associated characteristics and inappropriate use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 72, 755–764 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-016-2032-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-016-2032-2