Abstract

Although a number of reports suggest very low persistence with oral bisphosphonates, there is limited data on persistence with other anti-osteoporosis medications. We compare rates of early discontinuation (in the first year) with all available outpatient anti-osteoporosis drugs in Catalonia, Spain. We conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study using data from the SIDIAP database. SIDIAP contains computerized primary care records and pharmacy dispensing data for >80 % of the population of Catalonia (>5 million people). All SIDIAP participants starting an anti-osteoporosis drug between 1/1/2007 and 30/06/2011 (with 2 years wash-out) were included. We modelled persistence as the time between first prescription and therapy discontinuation (refill gap of at least 6 months) using Fine and Gray survival models with competing risk for death. We identified 127,722 patients who started any anti-osteoporosis drug in the study period. The most commonly prescribed drug was weekly alendronate (N = 55,399). 1-Year persistence ranges from 40 % with monthly risedronate to 7.7 % with daily risedronate, and discontinuation was very common [from 49.5 % (monthly risedronate) to 84.4 % (daily risedronate)] as was also switching in the first year of therapy [from 2.8 % (weekly alendronate) to 10 % (daily alendronate)]. Multivariable-adjusted models showed that only monthly risedronate had better one-year persistence than weekly alendronate and teriparatide equivalent, whilst all other therapies had worse persistence. Early discontinuation with available anti-osteoporosis oral drugs is very common. Monthly risedronate, weekly alendronate, and daily teriparatide are the drugs with the best persistence, whilst daily oral drugs have 40–60 % higher first-year discontinuation rates compared to weekly alendronate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The primary challenge in treating chronic illness today is that many patients do not take their medications correctly [1]. There has been much concern about the negative consequences of poor compliance and persistence with oral osteoporosis medications [2, 3].

Prior systematic reviews have documented that many patients discontinue oral medications for osteoporosis soon after treatment initiation, with a rapid drop in persistence in the first 3 months, followed by a slower decline over ensuing months: fewer than half the patients persist with osteoporosis drugs for a full year [4–6], with estimates ranging between 18 and 78 % for bisphosphonates [7]. The effectiveness of anti-osteoporotic drugs is compromised by this poor adherence to treatment: a significant proportion of patients abandon their treatment within 6 months of initiation and more than half stop treatment within the first year [8].

Low adherence is associated with less suppression of bone turnover and lower gains in bone mineral density. This in turn leads to higher fractures rates [9–11], medical costs, and greater healthcare utilization, including higher hospitalization [12, 13].

We therefore used a large primary care database that includes pharmacy invoice data and clinical information for more than 5 million people in Catalonia (Spain) to analyse and compare 1-year persistence with all outpatient anti-osteoporosis drugs in primary care settings.

Methods

Study Design

This is a population-based retrospective cohort study.

Source of Data

The Spanish public healthcare system covers practically the whole of the population. General practitioners (GPs) play an essential role, being responsible for primary healthcare, long-term prescriptions and specialist and hospital referrals. The data in this study were obtained from the SIDIAP Database (Sistema d‘Informació per al Desenvolupament de la Investigació en Atenció Primària). SIDIAP (www.sidiap.org) comprises primary care electronic medical records in Catalonia (North-East Spain), covering a population of about 5 million patients (80 % of the total population for the region) from 274 primary care practices (3414 GPs). Health professionals gather this information using ICD-10 codes and structured spreadsheets designed for the collection of variables relevant for primary care clinical management, including the country of origin, gender, age, height, weight, body mass index, smoking and drinking status, blood pressure measurements, preventive care provided, and blood and urine test results. Only GPs who achieve quality control standards can contribute to the SIDIAP database [14]. Encoding personal identifiers ensures the confidentiality of the information in the SIDIAP.

SIDIAP data have been used in many previous publications reporting of musculoskeletal conditions including osteoporosis and the epidemiology of fragility fracture in patients treated with oral bisphosphonates [15–19].

Study Population

We identified incident users of oral or subcutaneous anti-osteoporosis drugs [as available in primary care settings in Catalonia (Spain)] in the SIDIAP database between 01/01/2007 and 30/06/2010 and followed them up for at least 1 year.

Users of any anti-osteoporosis medications (excluding calcium or vitamin D supplements) in previous 2 years were excluded.

Drugs of Interest

We included oral drugs that can we use in primary care setting: daily (alendronate, risedronate, raloxifene, bazedoxifene and strontium ranelate), weekly (alendronate and risedronate), and monthly (ibandronate and risedronate). We also included subcutaneous daily teriparatide. We do not include zoledronic acid because it is hospital dispensed in our country and denosumab because it was not in the market in the study period. In Catalonia and during the study period, the presentations of these drugs were monthly (for example, a box of weekly alendronate contains four pills which covers 4 weeks, approximately 1 month).

Outcome

The main outcomes were rates of treatment cessation in the first year following therapy initiation.

As the best gap to identify the patients with bad compliance is not well defined, we decide to define persistence as time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy. Therapy cessation was defined on the basis of therapy dispensation refill gaps: if the gap between consecutive dispensing dates was more than 6 months, the gap based on the period over which repeat prescriptions was scheduled, and the last prescription of the drug before this gap was considered as the last prescription date. Our definition of persistence based on 6-month refill gap is an arbitrary decision based on two reasons: we have previously published on a cohort of oral bisphosphonate users extracted from the same data source using this gap [15] as have other authors using different datasets [20] and the nature of the local (catalan) GP prescription and reimbursement system—in our universal healthcare, GP provides repeat prescriptions every 3 months, and therefore, short gaps (<3–4 months) would artificially overestimate therapy cessation rates. One-year persistence (primary study outcome) was defined as the proportion of patients who received continuous drug dispensations for at least 365 days without a ≥6 month refill and without switching to another oral anti-osteoporosis drug. But since we are aware of the variability of adherence definitions, a sensitivity analysis using a 12-month gap (secondary definition) and another using de total dose prescribed [Daily Defined Doses (DDDs)] instead of time prescription was done.

Potential Confounders

A list of pre-specified potential confounders were considered and adjusted for in multivariable models (see below): age, gender, body mass index, smoking, alcohol drinking, Charlson co-morbidity index, number of previous fracture/s, use of oral corticosteroids, and concomitant therapy with aromatase inhibitors.

Statistical Analyses

We estimated persistence using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Risk of early (in the first year since therapy initiation) therapy discontinuation according to drug used was modelled using multivariable Fine and Gray regression models, accounting for a potential competing risk with death. In such models, unadjusted and multivariate-adjusted (for all confounders above) subhazard ratios (SHR) and 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) for one-year therapy cessation according to therapy group were estimated.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata for Mac version 12.

Results

We identified 127,722 incident users of anti-osteoporosis drugs in the SIDIAP database between 01/01/2007 and 30/06/2010. Only 1689 patients were followed less than 6 months (approximately 1 %). These patients were censored at end of follow-up, as usual in survival analyses. 118,829 (93.0 %) completed the study period, 970 (0.8 %) were lost to follow-up because they transferred out of the region, and 7923 (6.2 %) died in this period. Baseline characteristics of the study population according to follow-up status at the end of study (completed, lost to follow-up, or dead) are shown in Table 1. Patients who completed the study were as expected younger and with a lower Charlson co-morbidity index.

Table 2 shows the number and proportion of participants persisting, discontinuing, switching, and dead in the first year after therapy initiation and according to treatment group. The drugs with best 1-year persistence were monthly risedronate and weekly alendronate with persistence rates of 40 and 39.9 % respectively, whilst the one with lowest was daily risedronate (7.7 %). Discontinuation was common ranging from 84.4 % (daily risedronate) to 49.5 % (monthly risedronate), and when we studied therapy switching (to an alternative anti-osteoporosis drug) in the first year of treatment, the most commonly changed drug was daily alendronate (10.0 %) followed (in order) by monthly risedronate (9.9 %) and daily risedronate (7.9 %); in contrast, weekly alendronate (2.8 %), raloxifene (4.0 %), and bazedoxifene (4.3 %) were the less commonly changed medications.

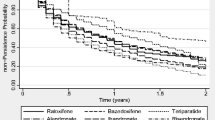

Detailed results for the Fine and Gray models to study the association between drug group and first-year therapy cessation risk are shown in Table 3. Monthly risedronate was the only drug with lower risk of discontinuation compared to weekly alendronate, with adjusted SHR 0.86 (95 % CI 0.83–0.89). Teriparatide users had similar risk of one-year discontinuation to users of weekly alendronate [adjusted SHR 1.02 (0.98–1.07)], and the rest of drugs showed an increased cessation risk. The drugs with the highest risk of discontinuation were those taken orally on a daily basis: adjusted SHR was 1.86 (1.74–1.99) for daily risedronate, 1.64 (1.52–1.77) for daily alendronate, 1.43 (1.40–1.45) for raloxifene, 1.41 (1.22–1.59) for bazedoxifene, and 1.51 (1.48–1.53) for strontium ranelate. Consistent with these results, Fig. 1 shows Kaplan–Meier curves for 1-year therapy persistence according to recommended drug.

Finally, Table 4 shows the results of the sensibility analysis using the primary definition of cessation (6-month gap), the secondary definition (12-month gap), and on the basis of days covered treatment (DDD). There were no significant differences when using different methods, only monthly risedronate shows worst compliance using the DDT definition but not with de secondary definition, and teriparatide shows worst compliance using both the 12-month gap and de DDT definition.

Discussion

This is the first study in Spain that compares persistence with all available anti-osteoporosis drugs in the same cohort.

We found that a substantial portion of patients (one-third to half) do not persist on treatment as initially recommended. Both cessation and therapy switching occur soon (in the first 1–3 months) after treatment initiation. Our findings are consistent with previously published studies [15, 21], but most of the studies published include only oral bisphosphonates.

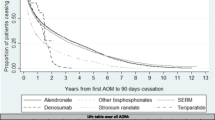

According to our data, 1-year persistence with daily drugs therapy varies from 7.5 to 32 %. Amongst users of weekly oral bisphosphonates, one-year persistence is slightly better, ranging between 30 and 40 %, and teriparatide seems to have similar persistence but still clearly insufficient to achieve therapeutic coverage. In the literature, one study in the United States reported some improvement in persistence with monthly bisphosphonate therapy [22]. But this is not consistent with our results, where users of monthly risedronate were likely to stop treatment compared to users of weekly alendronate (reference groups), but users of monthly ibandronate had worse persistence.

Our study presents worse medication-taking behaviour (1-year persistence of 33.7 %), which could be explained by a greater percentage of patients in primary prevention, and a greater percentage of men in the sample compared to similar ones. For example, Hadji et al. [21] found 1-year persistence with oral bisphosphonates of 27.9 % (using a shorter refill gap than ours, of >30 days), with no differences between monthly and weekly administration; Netelenbos et al. [20] found 1-year persistence of 43 %: 46 % with monthly, 42–53 % for weekly, and 23–40 % for daily medications, and they included patients with similar age to our study participants (69.2 years), or Confavreux et al. [8] found 1-year overall persistence of 34 % (50 % at best with monthly and 37 % for weekly). In addition, Lo et al. [23] studied persistence using the General Practice Research Database in women who had a first prescription for an oral bisphosphonate, oral raloxifene, or oral strontium ranelate in the study period: 44 % of women were continuing with osteoporosis therapy after 6 months, 32 % after 1 year, 16 % at 3 years, and 9 % at 5 years from initiation. Finally, Burden et al. [24] found better persistence: 63 % at one year, but participants were older (75.6 years), in the second-year persistence was 46 and 12 % at 9 years.

Finally, an underreported finding is that many patients who discontinue bisphosphonate therapy reinitiate treatment after an extended gap [25], but little is known about the extent to which patients after discontinuing treatment in the routine care restart or switch to other drugs in the same class. One previous study [24] identified that the proportion of patients that persisted with therapy declined from 63 % at 1 year to 12 % after 9 years. They also identified that most patients experienced one or more extended gaps in bisphosphonate therapy. For example, amongst the 213,029 new users with at least 5 years of follow-up, 25 % persisted with therapy for the full 5 years, 61 % experienced one (24 %) or more (37 %) extended gaps in therapy, and 14 % discontinued treatment without returning to bisphosphonate therapy. Using a more lenient 120-day permissible gap to define non-persistence, they note that persistence rates increased and fewer users were identified to have experienced extended gaps in drug therapy. For example, persistence at 1 year increased from 63 % using a 60-day permissible gap to 77 % when using a 120-day permissible gap. They found that 7 % of new bisphosphonate users switched to a different bisphosphonate within 1 year of treatment initiation, and this increased to more than a third of patients (37 %) over the entire duration of follow-up (5 years). Knowing this findings, and taking into account the nature of prescription in Catalonia, we chose de 6-month gap and compared with 12-month gap and also with de DDDs; this sensitivity analysis showed that the results were robust, and the definition chosen for assessment of persistence (length of refill gaps) was not relevant for estimating persistence.

Our study has several limitations. First, we cannot ensure that patients who receive treatment from community pharmacies (dispensations) actually take the purchased medication/s nor can we know the reason/s for therapy switching and/or cessation, which might also include medical decisions and patient issues (for examples concerns about medication or difficulties in remembering to take it). Second, this is an observational study, and although we adjusted for a number of co-variables, residual confounding is likely. Of special concern in pharmaco-epidemiological studies is confounding by indication, where patients receiving some specific therapies are given those for a reason (e.g., higher disease severity or contraindications). In addition, channelling bias due to “special” patient characteristics amongst users of recently launched medications in the study period (i.e., bazedoxifene or monthly risedronate) is likely. This would, however, partially explain the observed findings for these medications but not for all the other drugs included. Given all this, we cannot test for causality between treatment prescribed and resulting persistence, which would require experimental (randomized controlled) studies.

Strengths of our study are the high sample size and the representativeness of the data used: SIDIAP covers over 80 % of the total population of Catalonia, and the information is coded in actual practice conditions, different to the restrictive settings required for randomized controlled trials. In addition, the information gathered on community pharmacy dispensations is detailed and likely to be more reliable than patient reports or GP prescriptions.

Conclusions

Early discontinuation with available therapies for Osteoporosis is very common. In our data, users of monthly risedronate, weekly alendronate, and teriparatide have best persistence: about 40 % of patients on these therapies continue after 1 year. In contrast, users of oral daily drugs (bisphosphonates, SERMs, and strontium ranelate) have a 40–60 % higher one-year cessation risk than weekly ALN.

References

Seeman E, Compston J, Adachi J, Brandi ML, Cooper C, Dawson-Hughes B et al (2007) Non-compliance: the Achilles’ heel of anti-fracture efficacy. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 18(6):711–719

Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, Barr CE, Arvesen JN, Abbott TA et al (2006) Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc 81(8):1013–1022

Silverman SL, Schousboe JT, Gold DT (2011) Oral bisphosphonate compliance and persistence: a matter of choice? Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 22(1):21–26

Lekkerkerker F, Kanis JA, Alsayed N, Bouvenot G, Burlet N, Cahall D et al (2007) Adherence to treatment of osteoporosis: a need for study. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 18(10):1311–1317

Imaz I, Zegarra P, González-Enríquez J, Rubio B, Alcazar R, Amate JM (2010) Poor bisphosphonate adherence for treatment of osteoporosis increases fracture risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 21(11):1943–1951

Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM (2007) A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 18(8):1023–1031

Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S, Miller RM, Halbert RJ (2007) Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc 82(12):1493–1501

Confavreux CB, Canoui-Poitrine F, Schott A-M, Ambrosi V, Tainturier V, Chapurlat RD (2012) Persistence at 1 year of oral antiosteoporotic drugs: a prospective study in a comprehensive health insurance database. Eur J Endocrinol Eur Fed Endocr Soc 166(4):735–741

Rabenda V, Mertens R, Fabri V, Vanoverloop J, Sumkay F, Vannecke C et al (2008) Adherence to bisphosphonates therapy and hip fracture risk in osteoporotic women. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 19(6):811–818

Landfeldt E, Ström O, Robbins S, Borgström F (2012) Adherence to treatment of primary osteoporosis and its association to fractures—the Swedish Adherence Register Analysis (SARA). Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 23(2):433–443

Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, Huybrechts KF, Raggio G, Naujoks C (2004) The impact of compliance with osteoporosis therapy on fracture rates in actual practice. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 15(12):1003–1008

McCombs JS, Thiebaud P, McLaughlin-Miley C, Shi J (2004) Compliance with drug therapies for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis. Maturitas 48(3):271–287

Olsen KR, Hansen C, Abrahamsen B (2013) Association between refill compliance to oral bisphosphonate treatment, incident fractures, and health care costs–an analysis using national health databases. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 24(10):2639–2647

Wilkes MM, Navickis RJ, Chan WW, Lewiecki EM (2010) Bisphosphonates and osteoporotic fractures: a cross-design synthesis of results among compliant/persistent postmenopausal women in clinical practice versus randomized controlled trials. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 21(4):679–688

Prieto-Alhambra D, Pagès-Castellà A, Wallace G, Javaid MK, Judge A, Nogués X et al (2014) Predictors of fracture while on treatment with oral bisphosphonates: a population-based cohort study. J Bone Miner Res Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 29(1):268–274

Pagès-Castellà A, Carbonell-Abella C, Avilés FF, Alzamora M, Baena-Díez JM, Laguna DM et al (2012) Burden of osteoporotic fractures in primary health care in Catalonia (Spain): a population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 13:79

Premaor MO, Compston JE, Fina Avilés F, Pagès-Castellà A, Nogués X, Díez-Pérez A et al (2013) The association between fracture site and obesity in men: a population-based cohort study. J Bone Miner Res Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 28(8):1771–1777

Reyes C, Estrada P, Nogués X, Orozco P, Cooper C, Díez-Pérez A et al (2014) The impact of common co-morbidities (as measured using the Charlson index) on hip fracture risk in elderly men: a population-based cohort study. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 25(6):1751–1758

Martinez-Laguna D, Tebe C, Javaid MK, Nogues X, Arden NK, Cooper C et al (2015) Incident type 2 diabetes and hip fracture risk: a population-based matched cohort study. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 26(2):827–833

Netelenbos JC, Geusens PP, Ypma G, Buijs SJE (2011) Adherence and profile of non-persistence in patients treated for osteoporosis–a large-scale, long-term retrospective study in The Netherlands. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 22(5):1537–1546

Hadji P, Claus V, Ziller V, Intorcia M, Kostev K, Steinle T (2012) GRAND: the German retrospective cohort analysis on compliance and persistence and the associated risk of fractures in osteoporotic women treated with oral bisphosphonates. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 23(1):223–231

Brookhart MA, Avorn J, Katz JN, Finkelstein JS, Arnold M, Polinski JM et al (2007) Gaps in treatment among users of osteoporosis medications: the dynamics of noncompliance. Am J Med 120(3):251–256

Lo JC, Pressman AR, Omar MA, Ettinger B (2006) Persistence with weekly alendronate therapy among postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 17(6):922–928

Burden AM, Paterson JM, Solomon DH, Mamdani M, Juurlink DN, Cadarette SM (2012) Bisphosphonate prescribing, persistence and cumulative exposure in Ontario, Canada. Osteoporos Int J Establ Result Coop Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA 23(3):1075–1082

Domínguez-Berjón MF, Borrell C, Cano-Serral G, Esnaola S, Nolasco A, Pasarín MI et al (2008) Constructing a deprivation index based on census data in large Spanish cities(the MEDEA project). Gac Sanit SESPAS 22(3):179–187

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors, C Carbonell-Abella, A. Pages-Castella, MK Javaid, X Nogues, AJ Farmer, C Cooper, A Diez-Perez, and D Prieto-Alhambra, declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carbonell-Abella, C., Pages-Castella, A., Javaid, M.K. et al. Early (1-year) Discontinuation of Different Anti-osteoporosis Medications Compared: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Calcif Tissue Int 97, 535–541 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-015-0040-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-015-0040-3