Abstract

Summary

Our systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies indicated that the use of antipsychotics was associated with a nearly 1.5-fold increase in the risk of fracture. First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) appeared to carry a higher risk of fracture than second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).

Introduction

The risk of fractures associated with the use of antipsychotic medications has inconsistent evidence between different drug classes. A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate whether there is an association between the use of antipsychotic drugs and fractures.

Methods

Searches were conducted through the PubMed and EMBASE databases to identify observational studies that had reported a quantitative estimate of the association between use of antipsychotics and fractures. The summary risk was derived from random effects meta-analysis.

Results

The search yielded 19 observational studies (n = 544,811 participants) with 80,835 fracture cases. Compared with nonuse, use of FGAs was associated with a significantly higher risk for hip fractures (OR 1.67, 95% CI, 1.45–1.93), and use of second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) was associated with an attenuated but still significant risk for hip fractures (OR 1.33, 95% CI, 1.11–1.58). The risk of fractures associated with individual classes of antipsychotic users was heterogeneous, and odds ratios ranged from 1.24 to 2.01. Chlorpromazine was associated with the highest risk (OR 2.01, 95% CI 1.43–2.83), while Risperidone was associated with the lowest risk of fracture (OR 1.24, 95% CI 0.95–1.83).

Conclusions

FGA users were at a higher risk of hip fracture than SGA users. Both FGAs and SGAs were associated with an increased risk of fractures, especially among the older population. Therefore, the benefit of the off-label use of antipsychotics in elderly patients should be weighed against any risks for fracture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Antipsychotic medications have been increasingly used in the elderly patients, defined as individuals older than 65 years of age, for the treatment of dementia, delirium, and other psychiatric status [1, 2]. In recent years, concerns have been raised about the long-term safety profile of antipsychotic medications, including potential adverse effects such as increased risk of respiratory infections and cerebrovascular disease [1, 3–6]. The possible association between antipsychotic treatment and another adverse event, hip/femur fractures, has received much interest during recent years [7–9] and was postulated that the use of antipsychotics may have led to an increased tendency to fall as a result of antipsychotics-related orthostatic hypotension or sedation [10]. In addition to severe vitamin D deficiency due to mineralization defect in the elderly patients, long-term use of some antipsychotic medications have been previously associated with hyperprolactinemia reduced 25(OH)D concentrations, resulting in defective bone mineralization and higher propensity for hip and femur fractures from falls [11, 12].

Several epidemiologic studies have suggested an association between antipsychotic treatment and hip and femur fractures [7, 13–15]. However, results of these studies have been inconsistent in the strength of association. Whether antipsychotic treatment may result in clinically significant hip and femur fracture outcome is still much debated. In addition, it remains unclear whether second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), which have a different adverse effect profile than first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs), may still increase the risk of fracture.

Osteoporosis-related hip and femur fractures are a major public health concern. A survey conducted in the USA reports that an estimated two million people suffer from osteoporotic fractures yearly, with a 1-year mortality of 20% [16]. Given the widespread use of antipsychotics and the high burden of morbidity and mortality of hip and femur fracture in the elderly, it is important to determine whether there is a relationship between antipsychotics use and risk of hip and femur fracture. Therefore, we performed a systematic review with meta-analysis of existing observational studies to evaluate any association between the use of antipsychotics and risks of fractures and to explore potential sources of heterogeneity among study results. We also investigated whether pharmacological differences between FGAs and SGAs were related to the occurrence of fractures.

Methods

Data sources and searches

The Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines were utilized for meta-analyses of observational studies [17]. A comprehensive search was conducted in the PubMed database from 1965 to May 2016 and EMBASE databases from 1974 through May 2016. All available years were searched without language restrictions, and the following words were used as search terms: antipsychotics, Chlorpromazine, Haloperidol, Bromperidol, Fluphenazine, Zuclopenthixol, Pentixol, Flupentixol, Levopromazine, Perphenazine, Pimozide, Penfluridol, Sulpiride, Amisulpride, Amoxapine, Asenapine, Aripiprazole, Blonanserine, Clozapine, Iloperidone, Melperone, Olanzapine, Risperidone, Paliperidone, Quetiapine, Sertindole, Lurasidone, Ziprasidone, fall, osteoporosis, and fracture. Bibliographies of all retrieved articles were also scanned for additional relevant articles. Two independent reviewers performed article selection, data extraction, and assessment of risk of bias. All disagreements were resolved by consensus. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (i) observational studies, with either cohort or case-control design; (ii) non-antipsychotic users were served as the reference group; (iii) reported fracture outcome risks associated with use of antipsychotics; and (iv) adequate data were provided to extract risk estimates. We excluded studies that use FGAs as a reference group or studies which only reported bone density changes. Clarification of data was requested from original investigators on an individual basis.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two trained reviewers independently conducted study selection, data abstraction, and risk of bias assessment. We then evaluated the risk of fracture associated with both FGAs and SGAs. FGAs included haloperidol, thioridazine, chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, perphenazine, thiothixene, loxapine, trifluoperazine, mesoridazine, molindone, pimozide, and promazine, while SGAs included risperidone, olanzapine, clozapine, and quetiapine. When possible, we extracted adjusted effect estimates (odds ratios (ORs), relative risks (RRs), or hazard ratios) between outcome measures and the use of FGAs or SGAs with standard error. Otherwise, we calculated unadjusted risk ratio with 95% confidence interval using the raw data. “Comprehensive adjustments” were credited to the studies that adjusted by age, gender, ethnicity, comorbidities, and medications. The adjustments were considered as “fair” if residual confounders could have existed even though the studies have been adjusted for gender, age, and clinical characteristics. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through mutual consensus.

Data analysis

We qualitatively synthesized data and assessed pooled risk of fractures for different types of antipsychotics and patient population. Statistical analysis was conducted with Stata 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The Cochran Q χ 2 test and I 2 statistic were used to assess heterogeneity among studies. The I 2 statistic describes the total variation across studies attributable to heterogeneity rather than chance [18]. We calculated pooled estimates and 95% CIs of the risk for antipsychotic use on hip or femur fractures using random-effects models based on the DerSimoneon and Laird model to account for the uncertainty associated with statistical heterogeneity. For studies that reported risk of fracture for FGA, SGA, or individual agents separately, we calculated a summary risk estimate for each study. The summary effect estimates for each study were then pooled together to obtain an overall effect estimate. To explore sources of heterogeneity, we performed several sensitivity analyses by predefined study characteristics using random-effects models. Galbraith plots were used to visualize the impact of individual studies on the overall statistical test of heterogeneity, and meta-regression was used to evaluate the amount of heterogeneity in the subgroup analysis. Publication bias was examined by funnel plots and Egger’s test [19]. We used a “trim and fill” procedure to impute hypothetical missing studies due to publication bias and recalculate a pooled OR [20].

Results

Study selection

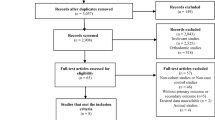

The search strategy identified 866 articles. Of these, 108 citations were excluded due to overlap, 726 articles were excluded on the basis of their title and abstract, and 3 articles were added after manual search from reference lists of reviewed literature. A total of 35 potentially relevant articles underwent detailed full-text review. After full-text review, we included 19 studies that met all eligibility criteria for final quantitative analysis [7, 8, 13–15, 21–34]. The number of articles excluded at each stage and the reasons for exclusion of each individual article at the full-text review stage is outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

Table 1 outlines the study characteristics of the 19 studies included in our meta-analysis. These 19 studies included 544,811 participants with 80,835 fracture cases from 12 case–control studies [7, 8, 13, 14, 25–27, 29–31, 33, 34] and 7 cohort studies [15, 21–24, 28, 32]. Six cohorts included only the elderly population, defined as those aged more than 65 years old [15, 21–24, 32], and seven cohorts included both adult patients of varying age groups [15, 21–24, 28, 32]. Two studies included only participants treated with FGAs [23, 29], 3 studies included only participants treated with SGAs [15, 22, 26], and the remaining 14 studies included patients treated with either FGAs or SGAs.

Study quality

The incorporated studies evaluated either hospital patients or nursing home residents, and all used appropriate case–control or cohort design (Table 1). The quality indicators for included studies are summarized in Table 2. All studies ascertained fracture outcome by using diagnostic codes on electronic medical records or ICD-9 CM codes on health insurance claims database. Only one study reported adjudication of fractures with knowledge of radiological findings. Most studies studied the exposure to antipsychotics in different risk window, different types, and different duration. The studies also varied in the adjusted covariates. All studies made appropriate adjustments for potential confounders in the multivariate analysis.

Use of antipsychotic medications and risk of fracture

Table 3 and Fig. 2 demonstrate an increased risk of fracture associated with use of any antipsychotics (pooled OR, 1.46, 95% CI 1.31–1.64, I 2 = 76.8%). Six studies evaluated the association between use of FGA and the risk of hip and femur fractures. Use of FGAs was significantly associated with increased risk of hip and femur fractures compared with non-users with a pooled OR of 1.67 (95% CI 1.45–1.93). There was moderate heterogeneity among studies (I 2 = 29.3%) (Table 3). Three individual FGAs were available for quantitative analyses. The pooled OR for hip and femur fractures was 2.01 (95% CI 1.43–2.83) for chlorpromazine, 1.93 (95% CI 1.35–2.76) for haloperidol, and 1.91 (95% CI 1.16–3.13) for thioridazine. Seven studies evaluated the association between SGA therapy and the risk of hip and femur fractures. As observed in FGA users, users of SGAs were also associated with increased risk of hip and femur fractures (pooled OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.11–1.58). However, significant heterogeneity was present among studies (I 2 = 66.9%). Unlike the findings with hip and femur fractures, use of SGAs was not associated with a significant risk of hip, wrist, or vertebra fractures (pooled OR 1.19; 95% CI 0.85–1.68, I 2 = 76.0%). Data were available to assess risk of all fractures with use of three specific SGAs. The pooled ORs for all fractures were 1.49 (95% CI 1.14–1.94) for olanzapine, 1.47 (95% CI 0.82–2.64) for quetiapine, and 1.24 (95% CI 0.95–1.62) for risperidone.

Sensitivity analysis

In the sensitivity analyses, we found that use of either FGAs or SGAs was associated with an increased the risk of fracture regardless of age, fracture sites, study designs, or background fracture incidence (Table 4). Galbraith plot (Fig. 3) analysis revealed that studies by Chatterjee S, Bolton JM, Howard L, and Fraser LA may be statistical outliers [14, 15, 22, 27]. Exclusion of the four studies did not change the effect estimate significantly (meta-regression p = 0.060). Compared with non-use, antipsychotic use in the elderly population was associated with an approximately 1.55-fold increase in the risk of fractures (RR = 1.55, 95% CI 1.36–1.76), although the difference was not statistically significant (meta-regression p = 0.483). Our analysis suggests that the associations were stronger in studies where the primary endpoint was hip fracture risk (pooled OR = 1.56, 95% CI 1.41–1.73) as compared with the fracture at any site (pooled OR = 1.20, 95% CI 1.01–1.43, meta-regression p = 0.015). Stratification of studies by study design factor did not reduce the heterogeneity of effect estimates, and the pooled ORs did not differ between case-control studies (pooled OR = 1.49 95% CI 1.29–1.73) and cohort studies (pooled OR = 1.41 95% CI 1.14–1.75). We noted that the strength of association increased from a RR of 1.37 to a RR of 1.52 as the background fracture incidence of the study population increased from <10 to ≥10%, but the change was not significant (meta-regression p = 0.229).

Publication bias

The test for publication bias was generally not significant, except that the Egger’s tests indicated preferred publication of positive results for SGA (p = 0.01) and haloperidol (p = 0.06). Trim-and-fill analysis showed that the risk of fracture remained significant for SGAs (OR 1.38, 1.10–1.72) and haloperidol (OR 1.93, 1.35–2.76) after presumed unpublished data were included for analysis. The results of Egger’s test indicated no evidence for publication bias in both FGA and SGA users (p = 0.85). Among FGA users, no significant evidence of potential publication bias was noted using the Egger’s test (p = 0.87). The Egger’s test of individual SGAs including olanzapine (p = 0.80), quetiapine (p = 0.81), and risperidone (p = 0.94) suggested no significant evidence of potential publication bias (Table 5).

Discussion

In this meta-analysis comprising 19 observational studies, pooled results indicated that use of any antipsychotics was associated with nearly 1.5-fold increase in the risk of fracture regardless of different study designs, sites of fracture, or age range of the study. Higher increases in risk were seen among elderly people, hip fracture site, and in populations with high background fracture incidence. There has also been previous disagreement about the type of antipsychotic medications associated with fracture risk, and we confirmed that risk exists among both FGAs and SGAs. For individual agents, Chlorpromazine seemed to be associated with the highest risk and risperidone seemed to be associated with the lowest risk. However, these results should be interpreted in the context of indication bias, statistical and clinical heterogeneity among studies.

Our findings are supported by two previous meta-analyses, which found that antipsychotic use was significantly associated with increased risk of fracture. Review by Takkouche et al. summarized 12 studies and reported a pooled OR of 1.59 (95% CI 1.27–1.98) for patients taking either an FGA or SGA [35]. A later review by Oderda was able to report a differential risk of fracture associated with use of FGAs (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.43–1.99) or SGAs (OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.14–1.49) [36]. Our up-to-date meta-analysis was able to complement previous studies by identifying nine additional eligible studies, computing a pooled summary estimate for individual agents, and determining important sources of heterogeneity through rigorous sensitivity analyses. In our analysis, heterogeneity of strengths of association may reflect differences in background incidence of fracture in the study population, the distribution of age, or differences in study design.

Antipsychotic medications have also been found previously to be associated with hypotension, sedation, and gait abnormalities; therefore, it is possible that falls are the mechanism by which these drugs increase fracture risk [37]. In our meta-analysis, we did not evaluate fall risk into our subgroup analysis due to the lack of studies that assessed this outcome. Among the 19 studies included in the meta-analysis, only two studies reported data on fall risk. Kolanowski et al. [28] found that among community-dwelling patients with dementia, use of antipsychotics was associated with a higher risk of fall (OR = 2.88, 95% CI 1.17–7.11) than no use. In their subgroup analysis, no significant difference was observed between FGAs (OR = 2.16, 95% CI 1.26–3.69) and SGAs (OR = 2.11, 95% CI 0.97–4.61). Fraser et al. [15] investigated the risk of falls with SGAs and found that SGA users had a 50% increased risk of fractures and falls. Assuming the observed association is causal, the estimated number-needed-to-harm with FGA therapy for hip fractures would be 495 in countries with high incidences of hip fracture such as Denmark (574/100,000) and 3952 in countries with low incidences of hip fracture such as Ecuador (73/100,000) [38, 39]. With an estimated 3% of the elderly population taking antipsychotic agents, use of antipsychotic agents may contribute substantially to the burdens of osteoporotic fracture in the elderly [40]. If we assume an OR of 1.55 and a prevalence of use of antipsychotic agents of 3%, we can conclude that antipsychotic medication accounts for 35.5% of hip fracture cases among people taking antipsychotic agents, and 1.6% of cases among the entire population. Among people living in nursing homes, where the prevalence of antipsychotic use is as high as 20%, an estimated 9.9% of hip fracture may be attributable to the use of antipsychotics.

The use of antipsychotic medications in the elderly population is not inevitable. A previous survey showed the main indications for antipsychotic use in the elderly are dementia (26.12%), anxiety (20.42%), and schizophrenia (6.62%) [41]. Except for schizophrenia, the psychiatric symptoms for patients with dementia or anxiety may be managed with alternative medication with smaller risk for fall or fracture. Non-pharmacological interventions, such as the use of memory assistive aids, physical activity, bright-light therapy, aromatherapy, and music therapy, have shown promising results in the management of the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in several studies [42, 43]. In addition, the survey also reported of the elderly receiving antipsychotic agents, 50.39% received SGAs and 51.88% received FGAs [41]. As this meta-analysis revealed, SGAs, especially risperidone, were associated with a lower risk for incident osteoporotic fracture as compared to FGAs. Therefore, for elderly patients at high risk for hip fractures but with compelling indications for antipsychotic treatment, SGAs, especially risperidone, should be considered in the absence of contraindications.

Results of our study should be interpreted in light of both strength and limitations. This meta-analysis has a large sample size and included studies on both FGAs and SGAs. Therefore, we were able to provide pooled effect sizes for several commonly used antipsychotic agents performed several sensitivity analyses to determine the source of heterogeneity. Second, combining the reported population statistics and effect estimates in this meta-analysis, we were able to quantify the population impact of antipsychotic use on the osteoporotic fracture for the elderly. Such figures may inform the drug use policy making in the future. However, there are several limitations needed to be discussed. First, there was substantial heterogeneity across the studies. Different study design, age, population characteristics, background fracture incidence rate, and the prevalent types of antipsychotic agents in use may be the sources of heterogeneity. We used random-effects models to account for the statistical heterogeneity, but it could not account for the clinical heterogeneity. The subgroup analysis did not investigate the associations specifically in each gender due to lack of data from individual studies. Second, the risk of bone fracture from antipsychotic therapy we observed could represent residual confounding, such as bone mineral density, lifestyle, and physical activity. Adjusting for confounding in observational studies may not be adequate as there could be other unknown confounders preventing the full adjusted analysis. However, most studies included in this meta-analysis used administrative database with rich covariate information. The unmeasured confounders, if any, must be strongly associated with both the use of antipsychotic medication and fracture outcome to account for the observed association.

In conclusion, our results support the idea that use of both FGAs and SGAs may increase the risk of hip and femur fractures, which is biologically plausible based on the potential fall risk and direct toxicity to bone mineralization of the antipsychotics [11, 44]. The 1.5-fold increased risk of fracture associated with antipsychotic use that the meta-analysis reveals suggests that antipsychotic medications may be responsible for more than 1.6% of hip and femur fracture cases in the elderly population, a figure that will likely increase as off-label use of antipsychotic medication in the elderly becomes more common. Fractures should become known alongside other documented associations and risks of respiratory infections, diabetes, and cerebrovascular disease [45]. Given the inherent limitation of observational studies, it may not be ethical to conduct a large randomized controlled trial with the specific aim on the harmful effect of antipsychotics on fractures. It is possible to perform meta-analysis analyses of previous randomized pharmaceutical controlled trials which assessed the effect of antipsychotics and collected information on fracture and fall to confirm the causality. In addition, future well-designed epidemiological studies can be conducted that examine the association between antipsychotic use and fracture risk. Such studies should incorporate more comprehensive adjustments for confounders, risk estimates based on individual antipsychotic agents and prescribing indications, and outcome measures that consider various fracture sites in addition to fall risk. Before such evidence is available, the benefit of off-label use of antipsychotic medications in elderly patients with conscious or behavioral disturbance should be weighed upon the increased risk of hip and femur fractures.

References

Jackson JW, Schneeweiss S, VanderWeele TJ, Blacker D (2014) Quantifying the role of adverse events in the mortality difference between first and second-generation antipsychotics in older adults: systematic review and meta-synthesis. PLoS One 9(8):e105376

Downing LJ, Caprio TV, Lyness JM (2013) Geriatric psychiatry review: differential diagnosis and treatment of the 3 D’s-delirium, dementia, and depression. Current psychiatry reports 15(6):1–10

Hung GC-L, Liu H-C, Yang S-Y, Pan C-H, Liao Y-T, Chen C-C, et al. Antipsychotic reexposure and recurrent pneumonia in schizophrenia: a nested case-control study. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2015; (VALUE!): 1,478–0.

Mehta S, Pulungan Z, Jones BT, Teigland C (2015) Comparative safety of atypical antipsychotics and the risk of pneumonia in the elderly. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 24(12):1271–1280

Mundet-Tudurí X, Iglesias-Rodal M, Olmos-Dominguez C, Bernard-Antoranz ML, Fernández-San Martín M, Amado-Guirado E (2013) Cardiovascular risk factors in chronic treatment with antipsychotic agents used in primary care. Rev Neurol 57(11):495–503

Nosè M, Recla E, Trifirò G, Barbui C (2015) Antipsychotic drug exposure and risk of pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 24(8):812–820

Hugenholtz GW, Heerdink ER, van Staa TP, Nolen WA, Egberts AC (2005) Risk of hip/femur fractures in patients using antipsychotics. Bone 37(6):864–870

Liperoti R, Onder G, Lapane KL, Mor V, Friedman JH, Bernabei R et al (2007) Conventional or atypical antipsychotics and the risk of femur fracture among elderly patients: results of a case-control study. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 68(6):1 478-934

Trifiró G, Sultana J, Spina E (2014) Are the safety profiles of antipsychotic drugs used in dementia the same? An updated review of observational studies. Drug Saf 37(7):501–520

Nielsen J, Correll CU, Manu P, Kane JM (2013) Termination of clozapine treatment due to medical reasons: when is it warranted and how can it Be avoided?[CME]. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 74(6):1 478-613

Stubbs B (2009) Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinaemia in patients with schizophrenia: considerations in relation to bone mineral density. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 16(9):838–842

Milovanovic DR, Stanojevic Pirkovic M, Zivancevic Simonovic S, Matovic M, Djukic Dejanovic S, Jankovic SM et al (2016) Parameters of calcium metabolism fluctuated during initiation or changing of antipsychotic drugs. Psychiatry investigation 13(1):89–101

Pouwels S, Van Staa T, Egberts A, Leufkens H, Cooper C, De Vries F (2009) Antipsychotic use and the risk of hip/femur fracture: a population-based case–control study. Osteoporos Int 20(9):1499–1506

Bolton JM, Metge C, Lix L, Prior H, Sareen J, Leslie WD (2008) Fracture risk from psychotropic medications: a population-based analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol 28(4):384–391

Fraser L-A, Liu K, Naylor KL, Hwang YJ, Dixon SN, Shariff SZ et al (2015) Falls and fractures with atypical antipsychotic medication use: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 175(3):450–452

Osteoporosis facts and statistics. International Osteoporosis Foundation; 2015. http://www.iofbonehealth.org/facts-and-statistics/index.html.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D et al (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA 283(15):2008–2012

Bown M, Sutton A (2010) Quality control in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 40(5):669–677

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315(7109):629–634

Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L (2007) Performance of the trim and fill method in the presence of publication bias and between-study heterogeneity. Stat Med 26(25):4544–4562

Rigler SK, Shireman TI, Cook-Wiens GJ, Ellerbeck EF, Whittle JC, Mehr DR et al (2013) Fracture risk in nursing home residents initiating antipsychotic medications. J Am Geriatr Soc 61(5):715–722

Chatterjee S, Chen H, Johnson ML, Aparasu RR (2012) Risk of falls and fractures in older adults using atypical antipsychotic agents: a propensity score–adjusted, retrospective cohort study. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 10(2):83–94

Caughey GE, Roughead EE, Pratt N, Shakib S, Vitry AI, Gilbert AL (2010) Increased risk of hip fracture in the elderly associated with prochlorperazine: is a prescribing cascade contributing? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 19(9):977–982

Nurminen J, Puustinen J, Piirtola M, Vahlberg T, Kivelä S-L (2010) Psychotropic drugs and the risk of fractures in old age: a prospective population-based study. BMC Public Health 10(1):1

Jalbert JJ, Eaton CB, Miller SC, Lapane KL (2010) Antipsychotic use and the risk of hip fracture among older adults afflicted with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 11(2):120–127

Dore DD, Trivedi AN, Mor V, Friedman JH, Lapane KL (2009) Atypical antipsychotic use and risk of fracture in persons with parkinsonism. Mov Disord 24(13):1941–1948

Howard L, Kirkwood G, Leese M (2007) Risk of hip fracture in patients with a history of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 190(2):129–134

Kolanowski A, Fick D, Waller JL, Ahern F (2006) Outcomes of antipsychotic drug use in community-dwelling elders with dementia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 20(5):217–225

Ray WA, Griffin MR, Schaffner W, Baugh DK, Melton LJ III (1987) Psychotropic drug use and the risk of hip fracture. N Engl J Med 316(7):363–369

Cumming RG, Klineberg R (1993) Psychotropics, thiazide diuretics and hip fractures in the elderly. Med J Aust 158(6):414–417

Lichtenstein MJ, Griffin MR, Cornell JE, Malcolm E, Ray WA (1994) Risk factors for hip fractures occurring in the hospital. Am J Epidemiol 140(9):830–838

Guo Z, Wills P, Viitanen M, Fastbom J, Winblad B (1998) Cognitive impairment, drug use, and the risk of hip fracture in persons over 75 years old: a community-based prospective study. Am J Epidemiol 148(9):887–892

Wang PS, Bohn RL, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Avorn J (2001) Zolpidem use and hip fractures in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 49(12):1685–1690

C-S W, Chang C-M, Tsai Y-T, Huang Y-W, Tsai H-J (2015) Antipsychotic treatment and the risk of hip fracture in subjects with schizophrenia: a 10-year population-based case-control study. The Journal of clinical psychiatry 76(9):1

Takkouche B, Montes-Martínez A, Gill SS, Etminan M (2007) Psychotropic medications and the risk of fracture. Drug Saf 30(2):171–184

Oderda LH, Young JR, Asche CV, Pepper GA (2012) Psychotropic-related hip fractures: meta-analysis of first-generation and second-generation antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs. Ann Pharmacother 46(7–8):917–928

Muench J, Hamer AM (2010) Adverse effects of antipsychotic medications. Am Fam Physician 81(5):617–622

Kanis JA, Odén A, McCloskey E, Johansson H, Wahl DA, Cooper CA (2012) Systematic review of hip fracture incidence and probability of fracture worldwide. Osteoporos Int 23(9):2239–2256

Cummings SR, Melton LJ (2002) Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 359(9319):1761–1767

Rapoport M, Mamdani M, Shulman KI, Herrmann N, Rochon PA (2005) Antipsychotic use in the elderly: shifting trends and increasing costs. International journal of geriatric psychiatry 20(8):749–753

Jano E, Johnson M, Chen H, Aparasu RR (2008) Determinants of atypical antipsychotic use among antipsychotic users in community-dwelling elderly, 1996–2004. Curr Med Res Opin 24(3):709–716

Cerga-Pashoja A, Lowery D, Bhattacharya R, Griffin M, Iliffe S, Lee J et al (2010) Evaluation of exercise on individuals with dementia and their carers: a randomised controlled trial. Trials 11(1):1

Yang M-H, Lin L-C, S-C W, Chiu J-H, Wang P-N, Lin J-G (2015) Comparison of the efficacy of aroma-acupressure and aromatherapy for the treatment of dementia-associated agitation. BMC Complement Altern Med 15(1):1

Higuchi T, Komoda T, Sugishita M, Yamazaki J, Miura M, Sakagishi Y et al (1987) Certain neuroleptics reduce bone mineralization in schizophrenic patients. Neuropsychobiology 18(4):185–188

Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, De Herdt A, Yu W, De Hert MI (2013) The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities increased in early schizophrenia? A comparative meta-analysis of first episode, untreated and treated patients. Schizophr Bull 39(2):295–305

Acknowledgements

We thank Yi-Han Sheu from Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, USA, for his comments and suggestions on our abstract, and Che-Wei Su at Mackay Medical College, Taiwan, for technical support and literature collection.

Author contributions

ICMJE criteria for authorship read and met for all authors. Designed the experiments/the study: SSC, and ChienCL. Analyzed the data: SHL, WTH, ChihCL, CCC, and SSC. Collected data/did experiments for the study: SHL, WTH, AEF, and YWT. Wrote the first draft of the paper: SHL, JW, and ChihCL. Reviewed the final draft: WTH, ChihCL, AEF, CCC, and ChienCL. Developed research concept and oversaw research: SSC and ChienCL. Approved the final draft: SSC and ChienCL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work is supported by research grants from Taiwan National Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 104–2314-B-002-039-MY3) and National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH. 105-P12). No funding bodies had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

The given name and surname of the co-author A. Esmaily-Fard were transposed in the original publication; the article has now been corrected in this respect.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-3938-y.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, SH., Hsu, WT., Lai, CC. et al. Use of antipsychotics increases the risk of fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 28, 1167–1178 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3881-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3881-3