Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

The COVID-19 pandemic and the desire to “flatten the curve” of transmission have significantly affected the way providers care for patients. Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgeons (FPMRS) must provide high quality of care through remote access such as telemedicine. No clear guidelines exist on the use of telemedicine in FPMRS. Using expedited literature review methodology, we provide guidance regarding management of common outpatient urogynecology scenarios during the pandemic.

Methods

We grouped FPMRS conditions into those in which virtual management differs from direct in-person visits and conditions in which treatment would emphasize behavioral and conservative counseling but not deviate from current management paradigms. We conducted expedited literature review on four topics (telemedicine in FPMRS, pessary management, urinary tract infections, urinary retention) and addressed four other topics (urinary incontinence, prolapse, fecal incontinence, defecatory dysfunction) based on existing systematic reviews and guidelines. We further compiled expert consensus regarding management of FPMRS patients in the virtual setting, scenarios when in-person visits are necessary, symptoms that should alert providers, and specific considerations for FPMRS patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19.

Results

Behavioral, medical, and conservative management will be valuable as first-line virtual treatments. Certain situations will require different treatments in the virtual setting while others will require an in-person visit despite the risks of COVID-19 transmission.

Conclusions

We have presented guidance for treating FPMRS conditions via telemedicine based on rapid literature review and expert consensus and presented it in a format that can be actively referenced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has drastically changed how patients are evaluated and treated and how they access ambulatory health care. Since there are currently no effective treatments or vaccines to prevent COVID-19, focus is placed on infection prevention through social distancing and quarantine. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have set forth recommendations to prevent infections in healthcare settings by decreasing or eliminating non-urgent office visits. Telehealth refers to any healthcare process that occurs remotely, including provider training or team meetings, whereas telemedicine specifically describes using technology to connect a patient to a provider. To enable patients to retain access to healthcare, many countries have revised regulations to allow health care providers to use telemedicine and receive appropriate reimbursement [1]. For example, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the USA have broadened access to, and reimbursement for, telemedicine services, allowing Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery (FPMRS) providers the opportunity to provide continuity of care to existing patients who would otherwise remain disconnected.

In the field of FPMRS, telemedicine can limit community exposure to the most vulnerable population while simultaneously granting patients the opportunity to establish or continue care with a provider [2]. However, no clear guidelines exist regarding administering remote care for FPMRS patients.

Our objective was to conduct an expedited review of the evidence and to provide guidance for management of common outpatient urogynecologic conditions to help guide our specialty as we transition the way we provide care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

Members of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) Collaborative Research in Pelvic Surgery consortium (SGS CoRPS) and the SGS Systematic Review Group (SGS SRG) participated in this project. The SGS CoRPS and SRG include members with expertise in clinical, surgical, and research management in FPMRS as well as systematic reviews and guideline development. No Institutional Review Board approval was required for this work.

We devised a list of questions and scenarios that FPMRS providers are likely to face as they engage patients virtually. We grouped these scenarios into diagnoses that would (1) likely require different treatment with telemedicine compared with in-person treatment or (2) would utilize accepted behavioral counseling and not deviate from current management paradigms. Expedited literature reviews were performed for four scenarios in which virtual management of patients would differ from direct visits [telemedicine in FPMRS patients, pessary management, urinary tract infection (UTIs), and urinary retention]. For scenarios in which the management via telemedicine would be similar to traditional conservative management (urinary and fecal incontinence, prolapse, defecatory dysfunction, and fecal incontinence), established algorithms and existing systematic reviews of conservative management were reviewed and summarized. Finally, expert consensus compiled and summarized the following; FPMRS conditions that are amenable to telemedicine management, urgent situations requiring in-person visits, symptoms that should alert FPMRS providers for possible COVID-19, and what FPMRS providers should consider when caring for patients with suspected or diagnosed COVID-19.

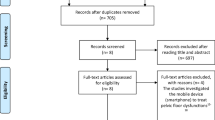

The methods, criteria, and literature flow for the expedited literature reviews, and salient meta-analysis details are reported in Appendix 1 [3]. Bullet-pointed summaries of our expedited literature reviews and expert consensus are listed in the body of this article. Additional information and details regarding the literature supporting these summaries can be found in Appendix 2.

Results

Telemedicine in FPMRS patients

The adoption and integration of telemedicine into a urogynecology practice is now possible, thanks to rapid advances in communications technology and widespread wireless access in many modern households. Still, FPMRS patient populations are diverse in age, socioeconomic status, and health literacy, and technologic devices and internet access are not universally available. Therefore, a multidimensional approach is necessary to provide a variety of options for patients seeking urogynecologic care.

Based on review of the literature (9 studies) [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12] and expert consensus (EC):

Patient satisfaction

-

Virtual visits provide similar patient satisfaction by building strong therapeutic relationships with patients through education, active listening, and shared decision-making [9].

-

FPMRS patients living in rural settings may be more likely to attend follow-up visits when conducted remotely, although providers must consider limited internet access and technical capabilities for some elderly patients [12].

Postoperative care

-

Patients whose postoperative visits are conducted using telemedicine reported high levels of satisfaction and experienced no increase in adverse events, emergency room visits, or primary care visits [10].

-

Postoperative patients after midurethral slings with no symptoms of incontinence or after native tissue pelvic organ prolapse repairs can be appropriately assessed with telephone follow-up [4, 10].

General principles for FPMRS telemedicine

-

Established patients not requiring a physical examination are ideal candidates for virtual visits (EC).

-

New patients appreciate establishing a relationship with a provider, even before an in-person visit is possible, and will benefit significantly from non-surgical treatment options [7].

-

Patients whose surgery has been canceled because of COVID-19 can replace their scheduled preoperative visit with a virtual discussion of alternative therapies as well as provide an opportunity for public health education related to COVID-19. In addition, rescheduling the patient’s surgery will confirm a plan for providing definitive care. Alternatively, previously scheduled preoperative visits could be held as patients are likely to eventually have surgery (EC).

-

There are many existing society websites with handouts and videos that can be used to supplement patient counseling (EC). They are available in many languages and in large print format. Some examples are:

-

International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) Patient Leaflets [13], https://www.yourpelvicfloor.org/leaflets/

-

American Urogynecologic Society, (AUGS) Voices for Pelvic Floor Disorders [14], https://www.voicesforpfd.org/resources/fact-sheets-and-downloads/

-

National Association for Continence [15], https://www.nafc.org/learning-library

Regulatory access to telemedicine Services in the US

Until COVID-19, telemedicine had not been utilized in most clinical settings. To expedite its use in the US, the Stafford Act, enacted in mid-March 2020, enabled the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to broaden access for Medicare telemedicine services. See Table 1 for CMS guidance to billing.

Pessary management

Seven studies provided data on risk of adverse events with long-term pessary use (without removal or cleaning) [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Nine additional articles were reviewed that provided information of interest during the pandemic [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Our analysis included three randomized controlled trials, three prospective cohorts, and one retrospective cohort. By meta-analysis (see Appendix 1), we estimated the following risks with continuous pessary use (no interval cleaning or examination) between 6 and 24 months: vaginal erosion or bleeding 5.0% (95% CI 1.9, 9.0), vaginal discharge 5.8% (95% CI 3.6, 8.5), vaginitis 1.8% (95% CI 0.2, 4.6), voiding dysfunction 4.7% (95% CI 1.4, 9.8), and fistula 0% (95% CI 0, 1.1).

Based on review of the literature (16 studies) and expert consensus:

-

Patients can safely extend the time interval between pessary cleanings to 6 months (and, in some cases, up to 24 months) with minimal risk of adverse events [17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

-

Patients capable of pessary removal and reinsertion should be encouraged to self-clean their pessary [27, 31,32,33,34,35].

-

Providers should consider empiric vaginal estrogen to minimize adverse events for patients not already using vaginal estrogen [17, 18, 28, 31, 33].

-

For patients reporting copious vaginal discharge or bleeding, it may be appropriate to encourage home self-removal and to observe for symptoms such as voiding dysfunction until patients can safely be evaluated in the office (EC).

-

Empiric treatment for bacterial vaginosis could be considered (EC).

Empiric treatment of UTI

In total, 60 articles provided information. Twenty-three contributed to the narrative summary and are cited in the paper. These included 2 RCTs [36, 37], 13 nonrandomized comparative studies [6, 8, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48], and 7 single group studies [49,50,51,52,53,54,55], and the remaining articles [5, 7, 39, 41, 43, 46, 50, 53, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83] included consensus documents, cost-effectiveness analyses, and narrative reviews.

Of note, most of our literature review and review of expert opinion was in line with the International Guidelines from the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) and European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Disease (ESMID) recommendations, including choice of antibiotic for first-line therapy [84]. With recurrent UTI patients, although recent recommendations by the American Urological Association (AUA), Canadian Urological Association (CUA), and Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine, and Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU) cited grade C evidence for cultures with every episode, the same level of evidence supports offering patient-initiated treatment when awaiting urine cultures [65].

Based on review of the literature (60 articles) and expert consensus:

-

Telemedicine with empiric antibiotic therapy is effective and lowers costs, but results in more prescribing and therefore may negatively impact antibiotic resistance [5, 8, 6, 57,58,59,60, 76].

-

The symptoms of dysuria, worsening frequency or urgency, gross hematuria, and lack of vaginal symptoms are significantly predictive of the presence of a UTI [44, 61].

-

Prior culture results within the past year correctly correspond to subsequent cultures and sensitivities and thus should be used to guide empiric therapy, even in neurogenic bladder patients [47, 48, 52, 62].

-

Patient factors such as age (> 65 years), immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, catheter use, UTIs in the last year, and recent exposure to antibiotics should be assessed during telemedicine visits as these factors predict resistance to first-line antibiotics [45, 63, 51, 54, 64]. Fever and diabetes are risk factors for more severe infections or bacteremia and might guide treatment decisions about triage in person [43]. Providers should bear in mind that fever and various atypical symptoms may also indicate COVID-19 infection.

-

Empiric treatments with either trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) or nitrofurantoin are cost-effective choices [42, 56, 85,86,87,88]. Uncomplicated UTIs should be treated with one of the following empiric antibiotic strategies as supported by cost guidance, guidelines, and antimicrobial susceptibility: (1) TMP-SMZ 160/800 mg orally twice daily for 3 days where antibiotic resistance does not exceed 20%, (2) nitrofurantoin monohydrate macrocrystals 100 mg orally twice daily for 5 days in patients with normal kidney function (CrCl > 30 ml/min), particularly if there are contraindications or high resistance to TMP-SMZ, (3) fosfomycin 3 g once, or (4) pivmecillinam 400 mg twice daily for 5 days [36, 40, 46, 50, 62, 64, 65, 38, 55, 81, 89, 53, 66, 77].

-

Antibiotic durations of 3–7 days are advisable and have better efficacy than single-dose therapy (with the exception of fosfomycin, which is an efficacious single dose regimen) [67, 72, 90].

-

Fluoroquinolone therapy should be reserved for higher-risk patients, locales where antibiotic resistance to alternative agents (particularly TMP-SMZ) exceeds 20%, or when poor kidney function is known in the patient [39, 41, 68, 78,79,80,81, 91].

-

Complicated UTIs in the current pandemic merit empiric treatment with a broader spectrum systemic fluoroquinolone antibiotic course to decrease hospital admissions, with plans to proceed to admission for parenteral antibiotics if severe symptoms occur or lack of response to oral antibiotics (e.g., intolerance to oral intake, high fever, severe pain, disorientation) [49, 69, 70, 92].

-

Elderly patients and patients with diabetes should be given broader spectrum antibiotics (e.g., cephalosporins or fluoroquinolone therapy) for longer durations (7 days vs. single dose vs. 3 days) [53, 66, 71,72,73, 82, 83].

-

Relief of symptoms can be used as a surrogate for UTI resolution in this pandemic (EC).

-

Other strategies to avoid antibiotics could include fluid hydration, cranberry supplements, or bladder soothants (e.g., phenazopyridine) (EC).

-

Laboratory alternatives include over-the-counter urine dipstick products, urine PCR [74], or utilizing remote laboratory locations to minimize exposure in hospital settings (EC).

-

Strategies to avoid UTIs that do not require in-person visits include vaginal estrogen or use of D-mannose 1000 mg twice daily [75] (EC).

-

Recurrent UTI patients may be offered patient-initiated treatment based on past urine cultures, as supported by grade C evidence in the AUA/CUA/SUFU guidelines. They further recommend culture with every episode but this may be suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic when the risk of healthcare exposure outweighs the need for culture [65] (EC).

Voiding dysfunction and retention

We found 23 articles, of which 10 had data extracted [93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102]. Thirteen additional articles provided information pertinent to management of voiding dysfunction during this pandemic [103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115].

Based on review of the literature (23 articles) and expert consensus:

-

Chronic urinary retention (PVR > 300 ml for > 6 months) puts patients at risk of upper urinary tract injury. Imaging and/or laboratory evaluation along with appropriate catheterization should be considered [111].

-

Factors that suggest a patient is at low risk for postoperative urinary retention (following pelvic surgery) include: voiding > 200 ml after being retrograde filled with 300 ml, voiding > 50% of the retrograde-filled volume, and women who subjectively feel that the postoperative force of their urinary stream is at least 50% of their baseline force of stream [102, 108, 112].

-

Regional anesthesia is unlikely to substantially increase the risk of postoperative urinary retention and can be considered for vaginal surgery in an effort to decrease the potential risk of aerosolization of COVID-19 with general anesthesia [113] (EC).

-

Clean intermittent self-catheterization (CISC) may be preferable to an indwelling catheter for urinary retention when possible [104, 107, 108]. Risk factors that predict poor success with CISC include obesity, poor dexterity, cognitive impairment, and pain with catheterization [105,106,107].

-

When patients call with symptoms of possible urinary retention, consider instruction in behavioral modification prior to recommending CISC. This includes encouraging the patient to create a relaxing environment with adequate time for voiding while taking slow deep breaths and relaxing their pelvic floor muscles [94]. Patients could also be instructed to double or triple void [116] or in the use of the Crede maneuver (expert consensus).

-

If behavioral modifications fail, patients should be given the option of CISC. A prescription for catheters can be called into a pharmacy (delivery may be available), and remote teaching of the CISC technique can be attempted. If video conferencing is available, patients could be taught to use a clean technique with a mirror. Initially, the patient lies down and inserts a small-gauge (e.g., 10, 12, or 14 French) catheter. When proficient with the mirror, she can be instructed to insert the catheter by feel in the sitting or standing position. Online instructional videos are also available (https://vimeo.com/261183016) [95, 117] and online patient handouts are available as well (https://www.yourpelvicfloor.org/media/Intermittent_Self_Catheterization.pdf) [13] (https://www.voicesforpfd.org/assets/2/6/ISC.pdf) [13, 14] (EC).

-

Patients with postoperative urinary retention who need indwelling catheterization can be instructed regarding safe removal of the catheter on postoperative day 7 at home without an office visit by cutting the balloon port and/or desufflating the catheter balloon. Consider having the patient remove the catheter early in the day to allow for an in-person office visit later on the same day if necessary [114].

-

While antibiotics may reduce the incidence of asymptomatic bacteriuria during short-term catheter use, there is no strong evidence supporting the use of prophylactic antibiotics after hospital discharge in women being catheterized for postoperative urinary retention [96, 97].

-

Antibiotic prophylaxis should not be routinely used in patients with long-term catheterization, and there is insufficient evidence to make recommendations about routine catheter change (e.g., every 2–4 weeks) in patients with long-term indwelling transurethral catheterization [115].

-

There is no strong evidence supporting the use of oral medication (e.g., alpha-adrenergic antagonists) in the treatment of voiding dysfunction or urinary retention in women [93, 99, 100].

Urinary incontinence

A recent systematic review was published on treatment options for women with urinary incontinence [118]. This systematic review focused on studies of adult women with stress urinary incontinence (SUI), urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), or mixed urinary incontinence (MUI); women were excluded if they were pregnant or hospitalized. We updated this review with additional studies published since August 2018 [118,119,120,121,122,123,124].

Based on this recent systematic review, six additional studies [118,119,120,121,122,123,124], and expert consensus:

-

SUI, UUI, and MUI can be discussed and treated with telemedicine (EC).

-

Behavioral therapy including bladder training, pelvic floor physical therapy or Kegel exercises, weight loss, and yoga have demonstrated significant improvement and/or complete resolution of SUI and UUI symptoms [125].

-

Patients currently treated with third-line treatments for UUI such as intradetrusor onabotulinum toxin A or percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation could revert back to behavioral modifications and medications (anticholinergic or ß3-adrenoceptor agonist) until they can return for in-person office visits (EC).

-

Consider balancing the risk of exposure to COVID-19 versus the risk of dementia from anticholinergic use [120]. It is unlikely that short-term use during healthcare interruption due to this pandemic will result in long-term dementia effects (expert consensus).

-

Consider the risk of hypertension with ß3-adrenoceptor agonists. However, two recent systematic reviews reported no difference in hypertension risk between mirabegron and placebo [121, 122].

-

-

Smartphone applications (apps) can be used to help teach and track Kegel exercises [123].

-

The free app Kegel Trainer or paid app Kegel Trainer Pro® were the highest rated apps based on a recent review [123].

Pelvic organ prolapse, defecatory dysfunction, and fecal incontinence

Existing AUGS Best Practice guidelines, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines, American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS) clinical practice guidelines, and systematic reviews were summarized to guide treatment of prolapse, fecal incontinence, and defecatory dysfunction via telemedicine [126,127,128,129]. Pelvic organ prolapse can be challenging to evaluate without a physical examination. However, the virtual visit provides an opportunity to counsel patients on the pathophysiology, possible treatment options, and techniques to prevent progression. Similarly, for defecatory dysfunction and fecal incontinence, conservative measures listed in the table can be initiated to help alleviate patients’ symptoms. It is important to note that a change in bowel habits, weight loss, and rectal bleeding may warrant referral to a gastroenterologist or colorectal surgeon to rule out colorectal cancer [128, 129]. Of note, if a patient reports new onset fecal incontinence or acute worsening of fecal incontinence, she should be screened for other COVID-19 symptoms and then referred for the appropriate care, as diarrhea is a possible symptom of COVID-19.

Pelvic organ prolapse

-

Only 10–20% of women will have an increase in prolapse stage over 2 years; therefore, most patients can be reassured regarding delay in surgical or pessary management [130, 131, 129].

-

Weight loss, reducing activities that strain the pelvic floor, smoking cessation, and avoiding constipation may improve symptoms and decrease progression of prolapse [132].

-

Pelvic Floor muscle training and exercises can decrease prolapse in some patients [132, 133].

-

For pelvic muscle exercises, providers may suggest online instructions (https://www.yourpelvicfloor.org/media/Pelvic_Floor_Exercises_RV2-1.pdf) [13] (https://www.voicesforpfd.org/assets/2/6/Bladder_Training.pdf) [14]. Home biofeedback devices can be used, such as Leva®, which is an FDA-cleared pelvic floor muscle trainer with visualization technology, smartphone applications, vaginal weights, virtual pelvic floor therapy appointments, or internet pelvic floor training (EC).

-

Encouraging patients to splint or insert a large tampon may help alleviate symptoms in cases of prolapse causing incomplete bladder emptying (EC).

Defecatory dysfunction

-

Dietary changes and fiber supplementation (insoluble fiber) can improve stool consistency and help with stool evacuation [126, 127].

-

Osmotic or stimulant laxatives can help defecatory dysfunction and postoperative constipation [126].

-

Position changes during bowel movements or a squatty potty can improve defecation [134].

-

Splinting vaginally or at the perineum may help women with incomplete evacuation from a rectocele (EC).

Fecal incontinence

-

Protective devices can be utilized [127]. These include pads or adult diapers, adhesive patches (e.g., butterfly pads), and skin care with protective ointments that are zinc based (EC).

-

A food diary can be used to identify triggers to avoid [127]. Triggers associated with loose stool can include sugar replacements, caffeine, and lactose.

-

Medications that may cause loose stool should be avoided [135]. Some common medications that cause diarrhea include: antacids, proton pump inhibitors, antibiotics, SSRIs, beta blockers, ACE inhibitors, metformin, and cholestyramine.

-

Dietary fiber (soluble) with increased fluid intake can provide more bulk to the stool and help achieve the ideal stool consistency [126, 136].

-

Consider medications ([126, 127]) to treat loose stools and help FI: [126, 127].

-

Bowel schedules, tap water enemas, glycerine, or bisacodyl suppositories can help patients to reliably evacuate the rectum [126].

-

A systematic review found anal plugs (not offered in the US) are poorly tolerated but effective [137].

Urgent situations

The COVID-19 pandemic presents a challenge for both patients and providers to determine the appropriate scenario requiring a more thorough evaluation, examination, and/or laboratory testing. When a provider is considering the necessity of an in-office visit, they must weigh the risks of COVID-19 exposure taking into account the current status of the outbreak in that specific region, the severity of the patient complaint, as well as the age and comorbidities of the patient. It appears that older age, diabetes, and immunosuppression increase the risk of morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19 infection [138]. As there are no guidelines on clinic visits during a pandemic for this specialty, group consensus was obtained, and a list of reasons that may require an in-person visit was generated (Table 2). Providers should also consider a clinic visit if there is a reasonable chance a physical examination or office diagnostic testing may change the course of treatment for an urgent complaint. One must also consider that the course of the COVID-19 pandemic will change over time, which might impact these recommendations.

COVID-19-specific concerns for FPMRS patients

Patients seen by urogynecologists are likely to have risk factors that increase the chance of complications from COVID-19. Thus, it is important for FPMRS providers to be aware of COVID-19 symptoms that should prompt a referral for further evaluation and testing. For example, upper respiratory symptoms and bowel changes are possible presenting symptoms for COVID-19. A patient with an increase in their stress incontinence due to a dry cough or worsened fecal incontinence due to diarrhea should trigger consideration for further COVID-19 screening based on the regional protocol.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has advised postponing elective cases until after the acute COVID-19 crisis abates [139]. General guidance to assist FPMRS and other surgical specialties with staged postponement of surgical cases has been published [140]. During the pandemic, there will be a need for urgent surgical intervention in some situations, and a plan for management of these non-elective cases is required. A brief review of perioperative considerations for non-elective cases including COVID-19 positive cases was generated (Table 3) [141, 142]. When discussing surgical intervention with patients negative for COVID-19 infection, surgeons should discuss the unique risks of nosocomial COVID-19 infection during the consent process, including the efforts undertaken to protect the patient and the challenges of preventing contamination. Also consideration should be placed on ERAS and same-day discharge to decrease risk and exposure to patients.

Discussion

In this review, we have explored conditions that FPMRS providers are likely to face as they engage patients virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic. We have reviewed the literature and summarized our findings in the sections above. Overall, behavioral and conservative management will be valuable as first-line treatments provided in a virtual setting (via phone or internet communication). There are situations that will require different treatments in the virtual setting than in person, and there are some that will require an in-person visit despite the risks of COVID-19 exposure and spread.

The strengths of this review include our use of expedited evidence review methods as well as the author team’s experience conducting systematic reviews and developing clinical practice guidelines, along with its advanced expertise in FPMRS. The main limitations to this review are the rapid nature of the review and the lack of data regarding many of the pertinent clinical questions. Our expedited evidence methods inevitably missed salient studies. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic is changing our world day by day, and it is impossible to forecast how this will impact our management of common FPMRS conditions in the months to come.

The COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented in terms of the scope and impact on the world’s healthcare systems. To control and prevent the spread of infection, FPMRS practices will need to utilize telemedicine to safely provide continuity of care to our patients. We have provided literature and expert-based guidance for the practicing FPMRS.

References

Smith AC, Thomas E, Snoswell CL, Haydon H, Mehrotra A, Clemensen J, Caffery LJ (2020) Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Telemed Telecare 1357633X20916567. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X20916567.

Rogers RG, Swift S. The world is upside down; how coronavirus changes the way we care for our patients. Int Urogynecol J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04292-7.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence-based Practice Center Program Rapid Review Guidance Document. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/funding/contracts/epc-vi/22-rapid_evidence_products_guidance.pdf. Accessed 4 Apr 2020.

Balzarro M, Rubilotta E, Trabacchin N, Mancini V, Costantini E, Artibani W, et al. A prospective comparative study of the feasibility and reliability of telephone follow-up in female urology: the patient Home Office novel evaluation (PHONE) study. Urology. 2020;136:82–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2019.10.021.

Barry HC, Hickner J, Ebell MH, Ettenhofer T. A randomized controlled trial of telephone management of suspected urinary tract infections in women. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:589–94.

Gordon AS, Adamson WC, DeVries AR. Virtual visits for acute, nonurgent care: A claims analysis of episode-level utilization. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e35. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6783.

Jones G, Brennan V, Jacques R, Wood H, Dixon S, Radley S. Evaluating the impact of a “virtual clinic” on patient experience, personal and provider costs of care in urinary incontinence: A randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0189174. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189174.

Mehrotra A, Paone S, Martich GD, Albert SM, Shevchik GJ. A comparison of care at e-visits and physician office visits for sinusitis and urinary tract infection. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:72–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.305.

Tates K, Antheunis ML, Kanters S, Nieboer TE, Gerritse MB. The effect of screen-to-screen versus face-to-face consultation on doctor-patient communication: an experimental study with simulated patients. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e421. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8033.

Thompson JC, Cichowski SB, Rogers RG, Qeadan F, Zambrano J, Wenzl C, et al. Outpatient visits versus telephone interviews for postoperative care: a randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:1639–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-03895-z.

Akbar N, Dobson EL, Keefer M, Munsiff S, Dumyati G. 1082. Hold the phone: antibiotic prescribing practices associated with nonvisit encounters for urinary tract infections (UTIs) in urology clinics. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6:S384. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofz360.946.

Schlittenhardt M, Smith SC, Ward-Smith P. Tele-continence care: A novel approach for providers. Urol Nurs. 2016;36:217–23.

International Urogynecologic Association (IUGA) Your Pelvic Floor Leaflets. https://www.yourpelvicfloor.org/leaflets/. Accessed 5 Apr 2020.

American Urogynecologic Association (AUGS) Voices for Pelvic Floor Disorders Fact Sheets and Downloads. https://www.voicesforpfd.org/resources/fact-sheets-and-downloads/. Accessed 5 Apr 2020.

National Association for Continence (NAFC) Urinary incontinence Education Learning Library. https://www.nafc.org/learning-library. Accessed 5 Apr 2020.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Telemedicine Healthcare Provider Fact Sheet. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Accessed 3 Apr 2020.

Miceli A, Fernández-Sánchez M, Polo-Padillo J, Dueñas-Díez J-L. Is it safe and effective to maintain the vaginal pessary without removing it for 2 consecutive years? Int Urogynecol J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04240-5.

Propst K, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, Tulikangas PK. Timing of office-based pessary care: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:100–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003580.

Tam M-S, Lee VYT, Yu ELM, Wan RSF, Tang JSM, He JMY, et al. The effect of time interval of vaginal ring pessary replacement for pelvic organ prolapse on complications and patient satisfaction: A randomised controlled trial. Maturitas. 2019;128:29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.07.002.

Cheung RYK, Lee JHS, Lee LL, Chung TKH, Chan SSC. Vaginal pessary in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:73–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001489.

Thys SD, Hakvoort RA, Asseler J, Milani AL, Vollebregt A, Roovers JP. Effect of pessary cleaning and optimal time interval for follow-up: a prospective cohort study. Int Urogynecol J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04200-8.

Chien C-W, Lo T-S, Tseng L-H, Lin Y-H, Hsieh W-C, Lee S-J. Long-term outcomes of self-management Gellhorn pessary for symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000770.

Lone F, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Karamalis G. A 5-year prospective study of vaginal pessary use for pelvic organ prolapse. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;114:56–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.02.006.

Wu V, Farrell SA, Baskett TF, Flowerdew G. A simplified protocol for pessary management. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:990–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00481-x.

Coolen A-LWM, Troost S, Mol BWJ, Roovers J-PWR, Bongers MY. Primary treatment of pelvic organ prolapse: pessary use versus prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:99–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3372-x.

Yang J, Han J, Zhu F, Wang Y. Ring and Gellhorn pessaries used in patients with pelvic organ prolapse: a retrospective study of 8 years. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;298:623–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-018-4844-z.

Ramsay S, Tu LM, Tannenbaum C. Natural history of pessary use in women aged 65 - 74 versus 75 years and older with pelvic organ prolapse: a 12-year study. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:1201–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-2970-3.

Collins S, Beigi R, Mellen C, O’Sullivan D, Tulikangas P. The effect of pessaries on the vaginal microenvironment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:60.e1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.07.024.

de A Coelho SC, Giraldo PC, Florentino JO, de Castro EB, LGO B, CRT J. Can the pessary use modify the vaginal microbiological flora? A cross-sectional study. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2017;39:169–74. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1601437.

Deng M, Ding J, Ai F, Zhu L. Clinical use of ring with support pessary for advanced pelvic organ prolapse and predictors of its short-term successful use. Menopause. 2017;24:954–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000859.

Manchana T. Ring pessary for all pelvic organ prolapse. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284:391–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-010-1675-y.

Dessie SG, Armstrong K, Modest AM, Hacker MR, Hota LS. Effect of vaginal estrogen on pessary use. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:1423–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3000-1.

Deng M, Ding J, Ai F, Zhu L. Successful use of the Gellhorn pessary as a second-line pessary in women with advanced pelvic organ prolapse. Menopause. 2017;24:1277–81. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000909.

Sasaki T, Agari T, Date I. Devices and practices for improving the accuracy of deep brain stimulation. No Shinkei Geka. 2018;46:751–62. https://doi.org/10.11477/mf.1436203809.

Kasper S. Editorial issue 4/2019. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2019;23:237. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2019.1688484.

Swedish Urinary Tract Infection Study Group. Interpretation of the bacteriologic outcome of antibiotic treatment for uncomplicated cystitis: impact of the definition of significant bacteriuria in a comparison of ritipenem acoxil with norfloxacin. Swedish urinary tract infection study group. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:507–13.

Jansåker F, Frimodt-Møller N, Bjerrum L, Dahl Knudsen J. The efficacy of pivmecillinam: 3 days or 5 days t.i.d against community acquired uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections—a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial study protocol. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:727. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-2022-0.

García-Rodríguez JA. Bacteriological comparison of cefixime in patients with noncomplicated urinary tract infection in Spain. Preliminary Results Chemotherapy. 1998;44(Suppl 1):28–30. https://doi.org/10.1159/000048461.

Guneysel O, Onur O, Erdede M, Denizbasi A. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole resistance in urinary tract infections. J Emerg Med. 2009;36:338–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.08.068.

Johnson JR, Stamm WE. Urinary tract infections in women: diagnosis and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:906–17. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-111-11-906.

Johnson L, Sabel A, Burman WJ, Everhart RM, Rome M, MacKenzie TD, et al. Emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance in outpatient urinary Escherichia coli isolates. Am J Med. 2008;121:876–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.04.039.

Kahan NR, Kahan E, Waitman D-A, Chinitz DP. Economic evaluation of an updated guideline for the empiric treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women. Isr Med Assoc J. 2004;6:588–91.

Leibovici L, Greenshtain S, Cohen O, Wysenbeek AJ. Toward improved empiric management of moderate to severe urinary tract infections. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:2481–6.

Mishra B, Srivastava S, Singh K, Pandey A, Agarwal J. Symptom-based diagnosis of urinary tract infection in women: are we over-prescribing antibiotics? Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:493–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02906.x.

Tchesnokova V, Riddell K, Scholes D, Johnson JR, Sokurenko EV. The uropathogenic Escherichia coli subclone sequence type 131-H30 is responsible for most antibiotic prescription errors at an urgent care clinic. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:781–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy523.

van der Donk CFM, van de Bovenkamp JHB, De Brauwer EIGB, De Mol P, Feldhoff K-H, Kalka-Moll WM, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and spread of multi drug resistant Escherichia coli isolates collected from nine urology services in the Euregion Meuse-Rhine. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47707. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047707.

Linsenmeyer K, Strymish J, Gupta K. Two simple rules for improving the accuracy of empiric treatment of multidrug-resistant urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:7593–6. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01638-15.

MacFadden DR, Ridgway JP, Robicsek A, Elligsen M, Daneman N. Predictive utility of prior positive urine cultures. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1265–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu588.

Bischoff S, Walter T, Gerigk M, Ebert M, Vogelmann R. Empiric antibiotic therapy in urinary tract infection in patients with risk factors for antibiotic resistance in a German emergency department. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-2960-9.

Bonfiglio G, Mattina R, Lanzafame A, Cammarata E, Tempera G, Italian Medici Medicina Generale (MMG) Group. Fosfomycin tromethamine in uncomplicated urinary tract infections: a clinical study. Chemotherapy. 2005;51:162–6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000085625.

Chiu C-C, Lin T-C, Wu R-X, Yang Y-S, Hsiao P-J, Lee Y, et al. Etiologies of community-onset urinary tract infections requiring hospitalization and antimicrobial susceptibilities of causative microorganisms. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2017;50:879–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2016.08.008.

Clark R, Welk B. The ability of prior urinary cultures results to predict future culture results in neurogenic bladder patients. Neurourol Urodyn. 2018;37:2645–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23713.

Datta R, Advani S, Rink A, Bianco L, Van Ness PH, Quagliarello V, et al. Increased fluoroquinolone-susceptibility and preserved nitrofurantoin-susceptibility among Escherichia coli urine isolates from women long-term care residents: A brief report. Open Access J Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.19080/OAJGGM.2018.04.555636.

Dokter J, Tennyson LE, Nguyen L, Han E, Sirls LT. The clinical rate of antibiotic change following empiric treatment for suspected urinary tract infections. Int Urol Nephrol. 2020;52:431–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-019-02327-7.

Neuzillet Y, Naber KG, Schito G, Gualco L, Botto H. French results of the ARESC study: clinical aspects and epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance in female patients with cystitis. Implications for empiric therapy. Med Mal Infect. 2012;42:66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2011.07.005.

Barry HC, Ebell MH, Hickner J. Evaluation of suspected urinary tract infection in ambulatory women: a cost-utility analysis of office-based strategies. J Fam Pract. 1997;44:49–60.

Bent S, Saint S. The optimal use of diagnostic testing in women with acute uncomplicated cystitis. Am J Med. 2002;113(Suppl 1A):20S–8S. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01056-2.

DeAlleaume L, Tweed EM, Bonacci R. Clinical inquiries. When are empiric antibiotics appropriate for urinary tract infection symptoms? J Fam Pract. 2006;55(338):341–2.

Ross AM. UTI antimicrobial resistance: tricky decisions ahead? Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:612–3.

Dixon T. Urinary tract infections. Management mayhem? Can Fam Physician. 1993;39:474–9.

Giesen LGM, Cousins G, Dimitrov BD, van de Laar FA, Fahey T. Predicting acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women: a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of symptoms and signs. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:78. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-11-78.

Vellinga A, Cormican M, Hanahoe B, Murphy AW. Predictive value of antimicrobial susceptibility from previous urinary tract infection in the treatment of re-infection. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:511–3. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp10X514765.

McGregor JC, Elman MR, Bearden DT, Smith DH. Sex- and age-specific trends in antibiotic resistance patterns of Escherichia coli urinary isolates from outpatients. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-25.

George CE, Norman G, Ramana GV, Mukherjee D, Rao T. Treatment of uncomplicated symptomatic urinary tract infections: resistance patterns and misuse of antibiotics. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4:416–21. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.161342.

Anger J, Lee U, Ackerman AL, Chou R, Chughtai B, Clemens JQ, et al. Recurrent uncomplicated urinary tract infections in women: AUA/CUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2019;202:282–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000000296.

Hanlon JT, Perera S, Drinka PJ, Crnich CJ, Schweon SJ, Klein-Fedyshin M, et al. The IOU consensus recommendations for empirical therapy of cystitis in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:539–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15726.

Andriole VT. When to do culture in urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;11:253–5; discussion 261. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0924-8579(99)00025-4.

Le TP, Miller LG. Empirical therapy for uncomplicated urinary tract infections in an era of increasing antimicrobial resistance: a decision and cost analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:615–21. https://doi.org/10.1086/322603.

Bader MS, Hawboldt J, Brooks A. Management of complicated urinary tract infections in the era of antimicrobial resistance. Postgrad Med. 2010;122:7–15. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2010.11.2217.

Hsueh P-R, Hoban DJ, Carmeli Y, Chen S-Y, Desikan S, Alejandria M, et al. Consensus review of the epidemiology and appropriate antimicrobial therapy of complicated urinary tract infections in Asia-Pacific region. J Inf Secur. 2011;63:114–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2011.05.015.

McCue JD. Rationale for the use of oral fluoroquinolones as empiric treatment of nursing home infections. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:157–64.

Lutters M, Vogt-Ferrier NB (2008) Antibiotic duration for treating uncomplicated, symptomatic lower urinary tract infections in elderly women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD001535. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001535.pub2.

Stapleton A. Urinary tract infections in patients with diabetes. Am J Med. 2002;113(Suppl 1A):80S–4S. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01062-8.

Wojno KJ, Baunoch D, Luke N, Opel M, Korman H, Kelly C, et al. Multiplex PCR based urinary tract infection (UTI) analysis compared to traditional urine culture in identifying significant pathogens in symptomatic patients. Urology. 2020;136:119–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2019.10.018.

Kranjčec B, Papeš D, Altarac S. D-mannose powder for prophylaxis of recurrent urinary tract infections in women: a randomized clinical trial. World J Urol. 2014;32:79–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-013-1091-6.

McQuiston Haslund J, Rosborg Dinesen M, Sternhagen Nielsen AB, Llor C, Bjerrum L. Different recommendations for empiric first-choice antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in Europe. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2013;31:235–40. https://doi.org/10.3109/02813432.2013.844410.

Naber KG, Wullt B, Wagenlehner FME. Antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection in premenopausal women. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38(Suppl):21–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.09.003.

Knottnerus BJ, Grigoryan L, Geerlings SE, Moll van Charante EP, Verheij TJM, Kessels AGH, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antibiotics for uncomplicated urinary tract infections: network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Fam Pract. 2012;29:659–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cms029.

Gupta K. Addressing antibiotic resistance. Dis Mon. 2003;49:99–110. https://doi.org/10.1067/mda.2003.10.

Nicolle L, Anderson PAM, Conly J, Mainprize TC, Meuser J, Nickel JC, et al. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women. Current practice and the effect of antibiotic resistance on empiric treatment. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:612–8.

Cohn EB, Schaeffer AJ. Urinary tract infections in adults. ScientificWorldJournal. 2004;4(Suppl 1):76–88. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2004.50.

File TM, Tan JS. Urinary tract infections in the elderly. Geriatrics. 1989;44(Suppl A):15–9.

Das R, Perrelli E, Towle V, Van Ness PH, Juthani-Mehta M. Antimicrobial susceptibility of bacteria isolated from urine samples obtained from nursing home residents. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:1116–9. https://doi.org/10.1086/647981.

Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, Wullt B, Colgan R, Miller LG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e103–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciq257.

Bradley MS, Beigi RH, Shepherd JP. A cost-minimization analysis of treatment options for postmenopausal women with dysuria. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:505.e1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.04.031.

Rothberg MB, Wong JB. All dysuria is local. A cost-effectiveness model for designing site-specific management algorithms. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:433–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.10440.x.

Fenwick EA, Briggs AH, Hawke CI. Management of urinary tract infection in general practice: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:635–9.

McKinnell JA, Stollenwerk NS, Jung CW, Miller LG. Nitrofurantoin compares favorably to recommended agents as empirical treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in a decision and cost analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86:480–8. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0800.

Concia E, Bragantini D, Mazzaferri F. Clinical evaluation of guidelines and therapeutic approaches in multi drug-resistant urinary tract infections. J Chemother. 2017;29:19–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1120009X.2017.1380397.

Faro S, Fenner DE. Urinary tract infections. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1998;41:744–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003081-199809000-00030.

Nicolle LE. Update in adult urinary tract infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2011;13:552–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-011-0212-x.

Naber KG. Which fluoroquinolones are suitable for the treatment of urinary tract infections? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;17:331–41.

Buckley BS, Lapitan MCM (2010) Drugs for treatment of urinary retention after surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD008023. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008023.pub2.

Burgio KL. Behavioral treatment of urinary incontinence, voiding dysfunction, and overactive bladder. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2009;36:475–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2009.08.005.

Dörflinger A, Monga A. Voiding dysfunction. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2001;13:507–12. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001703-200110000-00010.

Lavelle ES, Alam P, Meister M, Florian-Rodriguez M, Elmer-Lyon C, Kowalski J, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis during catheter-managed postoperative urinary retention after pelvic reconstructive surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:727–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003462.

Lusardi G, Lipp A, Shaw C (2013) Antibiotic prophylaxis for short-term catheter bladder drainage in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD005428. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005428.pub2.

Newman DK, Willson MM. Review of intermittent catheterization and current best practices. Urol Nurs. 2011;31(12–28):48 quiz 29.

Ramsey S, Palmer M. The management of female urinary retention. Int Urol Nephrol. 2006;38:533–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-005-5790-9.

Shokrpour M, Shakiba E, Sirous A, Kamali A. Evaluation the efficacy of prophylactic tamsulosin in preventing acute urinary retention and other obstructive urinary symptoms following colporrhaphy surgery. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:722–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_18_19.

Sutkin G, Lowder JL, Smith KJ. Prophylactic antibiotics to prevent urinary tract infection during clean intermittent self-catheterization (CISC) for management of voiding dysfunction after prolapse and incontinence surgery: a decision analysis. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:933–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-0885-y.

Tunitsky-Bitton E, Murphy A, Barber MD, Goldman HB, Vasavada S, Jelovsek JE. Assessment of voiding after sling: a randomized trial of 2 methods of postoperative catheter management after midurethral sling surgery for stress urinary incontinence in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:597.e1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.033.

Dieter AA, Wu JM, Gage JL, Feliciano KM, Willis-Gray MG. Catheter burden following urogynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:507.e1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.05.014.

Hakvoort RA, Nieuwkerk PT, Burger MP, Emanuel MH, Roovers JP. Patient preferences for clean intermittent catheterisation and transurethral indwelling catheterisation for treatment of abnormal post-void residual bladder volume after vaginal prolapse surgery. BJOG. 2011;118:1324–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03056.x.

Hentzen C, Haddad R, Ismael SS, Peyronnet B, Gamé X, Denys P, et al. Intermittent self-catheterization in older adults: predictors of success for technique learning. Int Neurourol J. 2018;22:65–71. https://doi.org/10.5213/inj.1835008.504.

Hentzen C, Haddad R, Ismael SS, Peyronnet B, Gamé X, Denys P, et al. Predictive factors of adherence to urinary self-catheterization in older adults. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38:770–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23915.

Kessler TM, Ryu G, Burkhard FC. Clean intermittent self-catheterization: a burden for the patient? Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28:18–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20610.

Meekins AR, Siddiqui NY, Amundsen CL, Kuchibhatla M, Dieter AA. Improving postoperative efficiency: an algorithm for expedited void trials after urogynecologic surgery. South Med J. 2017;110:785–90. https://doi.org/10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000733.

Mulder FEM, Hakvoort RA, de Bruin JP, van der Post JAM, Roovers J-PWR. Comparison of clean intermittent and transurethral indwelling catheterization for the treatment of overt urinary retention after vaginal delivery: a multicentre randomized controlled clinical trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1281–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3452-y.

Sassani JC, Stork A, Ruppert K, Bradley MS. Variables associated with an inability to learn clean intermittent self-catheterization after urogynecologic surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-03974-1.

Stoffel JT, Peterson AC, Sandhu JS, Suskind AM, Wei JT, Lightner DJ. AUA white paper on nonneurogenic chronic urinary retention: consensus definition, treatment algorithm, and outcome end points. J Urol. 2017;198:153–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2017.01.075.

Willis-Gray MG, Wu JM, Field C, Pulliam S, Husk KE, Brueseke TJ, et al. Is a postvoid residual necessary? A randomized trial of two postoperative voiding protocols. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000743.

Alas A, Hidalgo R, Espaillat L, Devakumar H, Davila GW, Hurtado E. Does spinal anesthesia lead to postoperative urinary retention in same-day urogynecology surgery? A retrospective review. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:1283–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-03893-1.

Shatkin-Margolis A, Yook E, Hill AM, Crisp CC, Yeung J, Kleeman S, et al. Self-removal of a urinary catheter after Urogynecologic surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:1027–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003531.

Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 international clinical practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:625–63. https://doi.org/10.1086/650482.

Madersbacher H, Cardozo L, Chapple C, Abrams P, Toozs-Hobson P, Young JS, et al. What are the causes and consequences of bladder overdistension? ICI-RS 2011. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:317–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.22224.

Society of Gynecologic Surgeons A Guide to Female Clean Intermitent Self Catheterization. https://vimeo.com/261183016. Accessed 4 Apr 2020.

Balk EM, Rofeberg VN, Adam GP, Kimmel HJ, Trikalinos TA, Jeppson PC. Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments for urinary incontinence in women: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of clinical outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:465–79. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-3227.

Simpson AN, Garbens A, Dossa F, Coyte PC, Baxter NN, McDermott CD. A cost-utility analysis of nonsurgical treatments for stress urinary incontinence in women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:49–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000502.

Richardson K, Fox C, Maidment I, Steel N, Loke YK, Arthur A, et al. Anticholinergic drugs and risk of dementia: case-control study. BMJ. 2018;361:k1315. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k1315.

Kelleher C, Hakimi Z, Zur R, Siddiqui E, Maman K, Aballéa S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of Mirabegron compared with Antimuscarinic monotherapy or combination therapies for overactive bladder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2018;74:324–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2018.03.020.

Chen H-L, Chen T-C, Chang H-M, Juan Y-S, Huang W-H, Pan H-F, et al. Mirabegron is alternative to antimuscarinic agents for overactive bladder without higher risk in hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Urol. 2018;36:1285–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-018-2268-9.

Barnes KL, Dunivan G, Jaramillo-Huff A, Krantz T, Thompson J, Jeppson P. Evaluation of smartphone pelvic floor exercise applications using standardized scoring system. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:328–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000563.

Nekkanti S, Wu JM, Hudson CO, Pandya LK, Dieter AA. A randomized trial comparing continence pessary to a disposable intravaginal device [poise impressa®] for the non-surgical management of stress urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;26:S95–6.

Balk E, Adam GP, Kimmel H, Rofeberg V, Saeed I, Jeppson P, Trikalinos T (2018) Nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in women: A systematic review update. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), Rockville (MD).

Wald A, Bharucha AE, Cosman BC, Whitehead WE. ACG clinical guideline: management of benign anorectal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1141–57; (Quiz) 1058. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2014.190.

Paquette IM, Varma MG, Kaiser AM, Steele SR, Rafferty JF. The american society of colon and rectal surgeons’ clinical practice guideline for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:623–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000397.

Ridgeway BM, Weinstein MM, Tunitsky-Bitton E. American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) best-practice statement on evaluation of obstructed defecation. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:383–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000635.

American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) Guidelines and Statements Committee, Carberry CL, Tulikangas PK, Ridgeway BM, Collins SA, Adam RA. American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) best practice statement: evaluation and counseling of patients with pelvic organ prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23:281–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000000424.

Bradley CS, Zimmerman MB, Qi Y, Nygaard IE. Natural history of pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:848–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000255977.91296.5d.

Gilchrist AS, Campbell W, Steele H, Brazell H, Foote J, Swift S. Outcomes of observation as therapy for pelvic organ prolapse: a study in the natural history of pelvic organ prolapse. Neurourol Urodyn. 2013;32:383–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.22298.

Dumoulin C, Hunter KF, Moore K, Bradley CS, Burgio KL, Hagen S, et al. Conservative management for female urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse review 2013: summary of the 5th international consultation on incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2016;35:15–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.22677.

Braekken IH, Majida M, Engh ME, Bø K. Can pelvic floor muscle training reverse pelvic organ prolapse and reduce prolapse symptoms? An assessor-blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:170.e1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.037.

Modi RM, Hinton A, Pinkhas D, Groce R, Meyer MM, Balasubramanian G, et al. Implementation of a defecation posture modification device: impact on bowel movement patterns in healthy subjects. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:216–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000001143.

ACOOAGCOPB, Dunivan GC, Chen CCG, Rogers RG (2019) ACOG practice bulletin no. 210: fecal incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 133:e260–e273. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003187.

Forte ML, Andrade KE, Butler M, Lowry AC, Bliss DZ, Slavin JL, Kane RL (2016) Treatments for Fecal Incontinence. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Deutekom M, Dobben A (2005) Plugs for containing faecal incontinence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD005086. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005086.pub2.

Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7.

American College of Surgeons COVID-19: Recommendations for Management of Elective Surgical Procedures. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-surgery. Accessed 2 Apr 2020.

Weber Lebrun EE, Moawad NS, Rosenberg EI, Morey TE, Davies L, Collins WO, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: staged Management of Surgical Services for gynecology and obstetrics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.038.

Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons SAGES and EAES Recommendations Regarding Surgical Response to COVID-19 Crisis. https://www.sages.org/recommendations-surgical-response-covid-19/. Accessed 2 Apr 2020.

Chen X, Liu Y, Gong Y, Guo X, Zuo M, Li J, et al. Perioperative Management of Patients Infected with the novel coronavirus: recommendation from the joint task force of the Chinese Society of Anesthesiology and the Chinese Association of Anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000003301.

Bacheller CD, Bernstein JM. Urinary tract infections. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81:719–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70542-3.

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted by the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Collaborative Research in Pelvic Surgery Consortium (SGS CoRPS) and Systematic Review Group (SRG).

Support

Funding provided by the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) supports assistance by methods experts in systematic reviews and other logistics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Grimes: protocol, project development, data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Balk: protocol, project development, data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Crisp: protocol, project development, data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Antosh: protocol, project development, data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Murphy: protocol, project development, data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Halder: data collection or management, data analysis,manuscript writing/editing.

Jeppson: data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Weber LeBrun: data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Raman: data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Kim-Fine: data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Iglesia: data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Dieter: data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Yurteri-Kaplan: data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Adam: project development, data collection or management, data analysis.

Meriwether: protocol, project development, data collection or management, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Financial disclaimers/conflict of interest

Grimes: Expert testimony for Johnson and Johnson.

Meriwether: Consultant for RBI medical, Travel reimbursements from SGS (voting board member as Research Chair), Book editing/authorship royalties from Elsevier.

Jeppson: Consultant for Johnson & Johnson.

Balk: Consultant for society for Gynecologic Surgeons and American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists.

Murphy: Expert witness for Johnson and Johnson, Boston Scientific, President of Soceity of Gynecologic Surgeons.

No conflicts: Balk, Crisp, Antosh, Adam, Weber LeBrun, Halder, Kim-Fine, Dieter, Raman, Yurteri-Kaplan, Iglesia.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Literature review methods

We conducted expedited literature reviews on four topics: (1) telemedicine, (2) pessary use, (3) empiric therapy for urinary tract infections (UTIs), and (4) dysfunctional urinary voiding (urinary retention).

For the expedited literature reviews we modified standard systematic review methods used by the SGS SRG and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence-based Practice Center Program [3]. Briefly, we first determined which among all the covered topics were amenable for literature review (and had not been recently addressed by existing systematic reviews or guidelines). For each of these four topics, we developed eligibility criteria by consensus. Based on these criteria, four formal literature searches were developed and run in PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Literature searches were conducted from database inception through March 29, 30, or 31, 2020. All searches were restricted to English language publications and excluded case reports, animal studies, and non-research articles (except narrative reviews). For all topics, we sought existing systematic reviews, primary studies, and pertinent narrative reviews.

Each literature search was entered into Abstrackr software (http://abstrackr.cebm.brown.edu/) and single screened by members of the SRG and CoRPS. Accepted abstracts were rescreened in Abstrackr by topic leaders. Remaining potentially relevant citations were entered into Google Sheets spreadsheets available to all researchers for tracking and basic data extraction. Immediately available full-text articles were retrieved and rescreened for eligibility by team members.

Data from studies of long-term pessary use adverse events were extracted into a Google Sheet file to capture study and pessary characteristics and event rate data. For other topics, team members culled pertinent information from relevant articles.

Telemedicine in FPMRS patients

Regarding telemedicine, we sought articles on effective approaches, and pitfalls, of telemedicine, virtual healthcare, and care by telephone for women with urogynecologic issues (e.g., urinary or defecatory incontinence, urinary or defecatory voiding dysfunction, pelvic organ prolapse, and UTI).

Research question

-

1.

Are any virtual visit platforms tested with FPMRS patients or older women?

Study eligibility criteria (PICOS)

Population

-

Urogynecology

-

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive surgery (FPMRS) care

-

Incontinence, urinary

-

Incontinence, defecatory

-

Prolapse

-

Recurrent UTIs

-

Defecatory dysfunction, including obstructed defecation

-

Urinary voiding dysfunction, including retention

Interventions

-

Virtual healthcare, including telemedicine/telehealth, videoconference, telephone, Web-based, app-based, rural healthcare (regarding long-distance care)

Outcomes

-

(Primary) emergency/urgent in-person care

-

(Primary) adverse outcomes/complications

-

(Secondary) clinical (patient-centered) outcomes

-

(Secondary) receiving urogynecology care

Study design/article availability

-

Primary studies of any design except case reports and case series

-

Systematic review or guideline

-

N ≥ 10 per intervention (group)

-

English language publication

-

Article immediately available for review

Literature search strategies Inception through March 30, 2020.

MEDLINE via PubMed.

(“Telecommunications”[Mesh] or teleconsult* or Telemedicine or “Mobile Health” or mHealth* or Telehealth* or telerehabilitat* or eHealth or e-health or “rural health” or “Rural Health Services”[Mesh] OR “Telemedicine”[Mesh] OR ((“Patient Care”[Mesh] OR “Patient Care” OR “Therapeutics”[Mesh] OR therapy OR therapeutic OR “Health Services”[Mesh] OR health OR “Diagnosis” [Mesh] OR diagnosis OR “Professional-Patient Relations”[Mesh] OR “Patient Relations” OR “Health Services Accessibility”[Mesh] OR “Health Behavior”[Mesh]) AND (“Telecommunications”[Mesh] OR “Computer Communication Networks”[Mesh] or e-medicine or email or e-mail or Videoconferenc* or wireless or phone* or telephone*)))

AND

(“Uterine prolapse” OR “Vaginal prolapse” OR “Pelvic Organ Prolapse” OR “Urogenital Prolapse” OR “Vaginal Vault Prolapse” OR “Cystocele” OR “cystocoele” OR “Rectal Prolapse” OR “Rectocele” OR “rectocoele” OR “Visceral Prolapse” OR “Uterine Disease” OR “Overactive Bladder” OR “Overactive Detrusor Function” OR “Urinary incontinence” OR “detrusor instability” OR “Urinary Tract Infection” OR “Pyuria” OR “Urinary Retention” OR “Fecal incontinence” OR “Bowel incontinence” OR “Fecal soiling” OR “obstructed defecation” OR “Defecatory dysfunction” OR “Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive surgeon” OR “urogynecology” OR “Uterine Prolapse”[Mesh] OR “Pelvic Organ Prolapse”[Mesh] OR “Uterine Diseases”[Mesh] OR “Urinary Bladder, Overactive”[Mesh] OR “Urinary Incontinence”[Mesh] OR “Urinary Tract Infections”[Mesh] OR “Fecal Incontinence”[Mesh] OR “Constipation”[Mesh] OR “Urinary Retention”[Mesh])

NOT

(“address”[pt] or “autobiography”[pt] or “bibliography”[pt] or “biography”[pt] or “case reports”[pt] or “comment”[pt] or “congress”[pt] or “dictionary”[pt] or “directory”[pt] or “festschrift”[pt] or “government publication”[pt] or “historical article”[pt] or “interview”[pt] or “lecture”[pt] or “legal case”[pt] or “legislation”[pt] or “news”[pt] or “newspaper article”[pt] or “patient education handout”[pt] or “periodical index”[pt] or “comment on” or “case report”[pt] or “case series”[pt] or (“Animals”[Mesh] NOT “Humans”[Mesh]) OR rats[tw] or rat[tw] or cow[tw] or cows[tw] or chicken*[tw] or horse[tw] or horses[tw] or mice[tw] or mouse[tw] or bovine[tw] or sheep[tw] or ovine[tw] or murinae[tw] or cats[tw] or cat[tw] or dog[tw] or dogs[tw] or rodent[tw])

Limit to English.

Cochrane databases.

(teleconsult or Telemedicine or Mobile Health or mHealth or Telehealth or telerehabilitation or eHealth or e-health or “rural health” OR Telecommunication OR Computer or e-medicine or email or e-mail or Videoconference or wireless or phone or telephone)

AND

(Uterine prolapse OR Vaginal prolapse OR Pelvic Organ Prolapse OR Urogenital Prolapse OR Vaginal Vault Prolapse OR Cystocele OR cystocoele OR Rectal Prolapse OR Rectocele OR rectocoele OR Visceral Prolapse OR Uterine Disease OR Overactive Bladder OR Overactive Detrusor Function OR Urinary incontinence OR detrusor instability OR Urinary Tract Infection OR Pyuria OR Urinary Retention OR Fecal incontinence OR Bowel incontinence OR Fecal soiling OR obstructed defecation OR Defecatory dysfunction OR Female Pelvic Medicine OR urogynecology)

Literature and screening results

The combined (partially deduplicated) searches yielded 3670 citations. These were screened singly in full by seven team members. Among these, 140 citations were screened in, which were rescreened by a single team member, who selected 15 for further review. Two citations referred to the same study, and three other articles were not available. In total, 11 full-text articles were reviewed, 9 of which were considered useful and are cited in the paper.

Pessary management

Regarding pessary management, we sought studies that reported rates of adverse outcomes (erosion, vaginal bleeding, discharge, vaginitis, fistulas) in women with pessaries in situ for > 3 months.

Research questions

-

1.

How long can a pessary remain in place without removal/cleaning?

-

2.

What is the risk of complications (erosion, vaginal bleeding, discharge, vaginitis, fistulas) due to delayed removal, cleaning, and inspection of the vagina?

-

3.

Is there benefit or reduction in adverse events by placing patients on vaginal estrogen if they are not already using it?

Study eligibility criteria (PICOS)

Note that the literature search focused on Pessary Question 2.

Population

-

Women with pessaries in place

Intervention

-

Pessary in place for ≥ 4 weeks

Outcomes

-

Erosion

-

Abrasion

-

Vaginitis

-

Vaginal infection

-

Fistula

-

Vaginal discharge

-

Abnormal vaginal bleeding

-

Urinary tract infection

-

Other clinical adverse outcomes

Study design/article availability

-

Primary studies of any design except case reports and case series

-

Systematic review or guideline

-

N ≥ 10 per intervention (group)

-

English language publication

-

Article immediately available for review

Literature search strategies Inception through March 29, 2020.

MEDLINE via PubMed.

((“Pessaries”[Mesh] OR pessary OR pessaries OR (gellhorn not gellhorn[author]) or “incontinence dish”))

NOT

(“address”[pt] or “autobiography”[pt] or “bibliography”[pt] or “biography”[pt] or “case reports”[pt] or “comment”[pt] or “congress”[pt] or “dictionary”[pt] or “directory”[pt] or “festschrift”[pt] or “government publication”[pt] or “historical article”[pt] or “interview”[pt] or “lecture”[pt] or “legal case”[pt] or “legislation”[pt] or “news”[pt] or “newspaper article”[pt] or “patient education handout”[pt] or “periodical index”[pt] or “comment on” or “case report”[pt] or “case series”[pt] or (“Animals”[Mesh] NOT “Humans”[Mesh]) OR rats[tw] or rat[tw] or cow[tw] or cows[tw] or chicken*[tw] or horse[tw] or horses[tw] or mice[tw] or mouse[tw] or bovine[tw] or sheep[tw] or ovine[tw] or murinae[tw] or cats[tw] or cat[tw] or dog[tw] or dogs[tw] or rodent[tw])

Limit to English.

Cochrane databases.

[Pessaries] explode all trees OR pessary OR pessaries OR (gellhorn NOT (gellhorn):au) OR “incontinence dish.”

Literature and screening results

The combined (partially deduplicated) searches yielded 1659 citations. These were screened singly in full by six team members. Among these, 140 citations were screened in, which were rescreened by a single team member, who selected 85 for further review of which 15 articles were not available in full text. Upon full-text review, seven studies reported data on adverse events related to long-term use of pessaries (without removal and cleaning); nine articles provided additional information. They are cited in the paper.

Meta-analysis methods

We conducted random-effects model restricted maximum likelihood meta-analyses of the proportions of women with adverse events. To account for non-normal distribution, proportions were double arcsine transformed. Meta-analyses were conducted in OpenMetaAnalyst (http://www.cebm.brown.edu/openmeta).

Meta-analysis results

Seven studies (with 9 study arms) were included in meta-analyses. These are summarized in Appendix Table 4.

Empiric treatment of UTI

Regarding management of recurrent UTIs, we sought articles on treatment of UTIs when urine cultures are not available; these included articles on whether to empirically treat with antibiotics, and if so, which antibiotic regimens to use. We sought to answer or include articles addressing the following questions: (1) one antibiotic versus another(s) for complicated or uncomplicated UTIs; (2) different durations of the same antibiotic for complicated or uncomplicated UTIs; (3) most appropriate treatment of patients with diabetes with UTI symptoms; (4) most appropriate treatment of patients with neurogenic bladder with UTI symptoms; (5) cost-effectiveness of certain empiric management strategies; (6) predicting results of future culture from past culture(s); (7) predicting resistance or response to certain antibiotics based on patient characteristics; (8) risk factors for need for escalation of care (hospital admission and/or bacteremia) from community-acquired organism; (9) likelihood of a patient having a UTI based on symptomatology alone.

Research question

-

1.

What is the best way to treat single-incident UTIs in older, more complicated patients without urine culture?

-

2.

How should patients with known recurrent UTIs have UTI symptoms addressed if they cannot present for care?

Study eligibility criteria (PICOS)

Population

-

Women with history of recurrent UTIs (per study definition)

-

UTI in postmenopausal (or older) women with urogynecologic conditions (e.g., prolapse, incontinence)

Intervention

-

Management of UTI without urine culture

Comparator

-

None (single group studies)

-

Other management plans without urine culture (e.g., different antibiotic regimen)

-

Management with urine culture

Outcomes

-

(Primary) emergency/urgent in-person care

-

(Primary) adverse outcomes/complications

-