Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

The use of mesh in pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery has become a widespread treatment option, but carries a risk of specific complications. The objective was to report the rate and type of reoperation for mesh-related complications after pelvic organ prolapse surgery in an urogynecological referral center over a period of 8 years.

Methods

A retrospective study was carried out including all patients operated for a mesh complication after prolapse surgery between September 2006 and September 2014 in the urogynecology unit in Nîmes hospital.

Results

Sixty-nine mesh complications were recorded among the 67 patients included. Surgical treatment of mesh-related complications accounted for 7% of all pelvic surgeries performed in our center. Thirty-two patients (47.8%) were referred from other centers and 35 patients (52.2%) were initially operated in our unit. The global rate of reintervention for mesh-related complications after prolapse repair performed in our unit was 2.8%. Of 69 mesh complications, 48 patients (71.6%) had transvaginal mesh (TVM) and 19 patients (28.4%) sacrocolpopexy (SCP). The indication for surgery was a symptomatic or large vaginal erosion (47.8%), symptomatic mesh contraction (20.3%), and infection (11.6%). The most frequent primary symptom was pelvic/perineal pain or dyspareunia (33.3% of cases). The mean time between initial mesh surgery and the reoperation for a complication was 33.4 months (95% CI, 24.5 to 42.2). Eleven patients (15.9%) required several interventions. In total, 77.9% of patients experienced complete recovery of symptoms after surgical management.

Conclusion

In a referral center the global rate of reinterventions for mesh-related complications after POP repair is 2.8%. The surgical treatment of mesh complications appears to be a safe and effective procedure with cure of the symptoms in most cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse is a functional disease that has a significant impact on quality of life [1]. The prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse of POP-Q (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantitation system) stage 2 or higher ranges from 37 to 50% [2, 3]. Sacrocolpopexy (SCP) has long been considered the gold standard prosthetic intervention for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. This technique is highly reproducible, with a high success rate and a low recurrence rate [4, 5]. Vaginal native tissue repair is an alternative to abdominal repair of pelvic organ prolapse. Transvaginal meshes (TVM) were developed to maintain the advantage of the vaginal route, while reducing the risk of recurrent prolapse on examination compared with native tissue repair. However, TVM repair appears to be associated with a higher reoperation rate for complications than both transvaginal native tissue repair [6, 7] and SCP [6, 8].

Specific complications can occur with mesh-augmented prolapse repair, both with TVM and SCP, which can be due to the surgical procedure or the mesh itself. After receiving over 1,000 reports of complications, the US Food and Drug Administration published two alerts (in 2008, then in 2011) concerning the risks of transvaginal placement of surgical mesh to treat pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence [9]. Irrespective of the surgical approach, these complications can have serious consequences and require specialized surgical management. Various surgical techniques have been described for the treatment of mesh-related complications, ranging from simply transecting the mesh to complete removal [10–22].

The complication rates reported in the literature are highly variable, and authors do not always report how many of reoperations performed were for complications. According to many authors, complications mainly occur during the first few months after surgery [23–28], but some studies have reported cases of exposure that developed later, highlighting the need for long-term studies [29, 30].

We report herein the 8-year experience of a urogynecology center with specific expertise in the management of pelvic organ prolapse. The aim of this study was to report the rate and type of reoperations performed for mesh-related complications following pelvic organ prolapse repair.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

This retrospective study was conducted at Nîmes University Hospital, France.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee (IRB No. 15/02.01). All patients were informed about the study by letter, including an opt-out form to return to us if they did not wish to participate. Not returning the opt-out form was therefore equivalent to agreeing to inclusion in the study.

This study included all the reoperations performed at our urogynecology center between 1 October 2006 (date of the availability of computerized medical records) and 30 September 2014 for complications related to a mesh used for transvaginal or abdominal pelvic organ prolapse repair. Reoperations for prolapse recurrence or de novo stress urinary incontinence were excluded. Similarly, reoperations for early complications attributable to the procedure (hematoma, urinary tract injury, gastrointestinal injury, early occlusion) were excluded. Reoperation for mesh-related complications were identified from the descriptors on operating room records and the codes entered into the French nationwide hospital database (PMSI), corresponding to the various procedures performed. For each patient, the first surgery for a mesh-related complication performed at our hospital was termed the “index surgery,” the second surgery “index surgery +1,” and the third surgery “index surgery +2.”

All the data were obtained retrospectively from the patients’ medical records, including demographics (age, past medical and surgical history), details of the primary mesh repair (operative report), indication for reoperation (type of complication, symptoms, results of physical examination and diagnostic investigations), details of the reoperation (time from primary repair to reoperation, type of surgery performed, type of anesthesia, any perioperative complications, number of procedures performed, and operating times), and outcome after reoperation.

The 2011 International Urogynecological Association/international Continence Society (IUGA/ICS) classification [31] and the Clavien–Dindo classification [32] were used to classify mesh complications.

After reoperation, the patient was considered “cured” if she was symptom-free and the physical examination was normal, “cured with permanent morbidity” if radical and morbid treatment was performed, “improved” when the symptoms and/or clinical abnormalities were only incompletely corrected, and “failed” when her symptoms were unchanged or worse. In April 2015, the patients were contacted by telephone to re-assess the degree of cure achieved since the last consultation, confirm the absence of functional recurrence, and check that no additional surgical procedure had been performed at another center in the meantime. If the patient was uncontactable, we used data from the last available consultation.

At the same time, we also identified all the mesh placements for prolapse repair performed at Nîmes University Hospital during the study period (October 2006 to September 2014). This enabled retrospective evaluation and analysis of the overall reoperation rate for mesh-related complications after reconstructive pelvic surgery within our own center.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using Stata 11.1 software. Fisher’s exact test, Chi-squared tests, or Student’s t tests were used for statistical comparisons, with p < 0.05 as the significance level.

Surgical techniques

The procedures were performed under general or regional (spinal) anesthesia. A physical examination was performed at the start of the procedure. If rectal or bladder exposure was suspected, rectal examination or cystoscopy was performed if it had not been done previously.

If symptoms were associated with a well-circumscribed portion of the transvaginal or sacrocolpopexy mesh, the first-line treatment was partial mesh excision via the vaginal route where possible. Total mesh excision was carried out if partial excision failed and for larger exposures, severe symptoms, or abscesses. If transvaginal mesh excision was impossible or for rectopexy-related complications or abscesses involving a SCP mesh, an abdominal, preferably laparoscopic, approach was used.

Bladder extrusions were treated endoscopically or using an open transvesical approach. Fistulae were treated by complete removal of the mesh together with fistula repair. The surgical route depended on the type and location of the fistula, the vaginal route being the preferred option.

Concomitant procedures were performed for some patients during surgery for mesh-related complications including native tissue prolapse repair or transection or removal of a suburethral sling (SUS).

Results

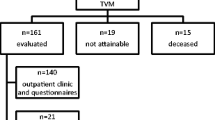

A total of 83 interventions for mesh-related complications were identified during the study period, in 67 patients. These patients had undergone TVM repair in 48 cases (71.6%) and SCP in 19 cases (28.4%) by laparoscopy (78.9%), laparotomy (15.8%), or robot-assisted laparoscopy (5.3%).

The primary repair was performed at our center in 35 cases (52.2%), whereas 32 patients (47.8%) had been referred from other centers, 4 (12.5%) of whom were referred after attempted treatment of the complication. Patient demographics at the time of index surgery are shown in Table 1. Most were postmenopausal with an average age of 61.8 years (95% CI: 59.4–64.3).

The primary repairs are described in Table 2, according to the location of the mesh, whether concomitant hysterectomy was performed, and whether the repair was performed at our center or elsewhere. The 8 hysterectomies in the TVM group were all total, whereas 2 out of 4 hysterectomies were subtotal in the SCP group. Polypropylene mesh was used in most of the TVM procedures (79.5%), whereas polyester mesh was predominantly used for the SCP procedures (66.7%). One patient had received a composite transvaginal mesh (polypropylene with porcine dermis) and two patients had received a biological graft (porcine dermis).

Two of the 67 patients had one complication associated with an anterior mesh and one associated with a posterior mesh. They occurred at different times and were considered to be two separate complications. In total, therefore, 69 complications were treated.

The commonest indication for the 69 interventions for mesh-related complications was vaginal exposure (33 out of 69, 47.8% of cases), followed by symptomatic mesh contraction (14/69, 20.3%), and pelvic abscess (8 out of 69, 11.6%). Four cases of bladder extrusion (4 out of 69, 5.8%) were reported when no bladder injury was mentioned during the primary mesh repair. The other surgical indications were: medically refractory neuropathic pain (3 out of 69, 4.3%), vesicovaginal fistula (2 out of 69, 2.9%), ureteral kinking (2 out of 69, 2.9%), rectovesical fistula (1 out of 69, 1.4%), rectovaginal fistula (1/69, 1.4%), and rectal extrusion (1/69, 1.4%). Figure 1 shows the patients’ primary symptom. The most frequent primary symptom was pain syndrome (33.3% of cases). Figure 2 shows all the symptoms reported by patients (the total exceeds 100% because some patients had several symptoms). Among patients with vaginal exposure, 34% complained of purulent vaginal discharge, but 24% were asymptomatic. The average erosion size on physical examination was 1.4 cm (95% CI: 0.97–1.9). In asymptomatic patients, surgical treatment was decided, mainly because of the size of erosion and the potential risk of secondary infection after failed local antiseptic and estrogenic treatment. Among the 14 patients with symptomatic contraction, 3 (21.4%) mainly had symptoms of voiding dysfunction, 3 patients had overactive bladder (21.4%), and 8 patients (57.1%) mainly had painful syndrome.

In the patients with neuropathic pain, diagnostic investigations were often normal and the physical examination uninformative. Surgical treatment was indicated if the pain persisted despite therapy with systemic analgesics and nerve blocks.

Patients operated for symptomatic contraction with voiding dysfunction had low urinary flow rates and/or postvoid residual (Qmax <12 mL/s or postvoid residual urine volume >200 mL). Ultrasound of the mesh showed urethral kinking associated with an anterior mesh positioned under the bladder neck (no distance between the lower margin of the anterior mesh and the bladder neck) and a severe contraction of the mesh (thickness of the mesh with a reduction of the surface area of the implanted mesh on ultrasonography).

The 2 cases of ureteral kinking occurred after TVM and were diagnosed in patients with abdominal and low back pain and confirmed with ureterohydronephrosis on imaging. One patient had renal failure with bilateral ureteral kinking.

The 69 complications in this series were classified using the Clavien–Dindo system as IIIa in 8.4% of complications (regional anesthesia required for index surgery) or IIIb in 91.6% of complications (general anesthesia required). The IUGA system CTS codes of these surgically treated mesh-related complications are shown in Table 3. Accurate coding was impossible for many patients. For 24 patients with vaginal exposure (72.7%), classification of the site as S1 or S2 was unreliable because the available operative reports did not mention the exact location of the erosion. Similarly, the size of the exposure was unknown for 13 patients with a vaginal erosion (39.4%), resulting in imprecise coding of its category (C2 or C3).

The surgical procedures performed to treat each type of complication are shown in Table 4. A total of 83 interventions were performed to manage the 69 complications in this series. During index surgery, mesh removal was mainly partial in 45 interventions (65.2%), including two combined with fistula repair, and total in 18 interventions (26.1%), including one combined with fistula repair.

The reoperations were performed via a transvaginal approach in 82.6% of cases, by laparoscopy in 8.7% of cases, via an open transvesical approach in 4.3% of cases, by cystoscopy in 2.9% of cases, and through a transanal approach in 1.4% of cases.

The average operating time for index surgery was 83 min (95% CI: 65.4–100.7): 102 min for sacrocolpopexy mesh-related complications (95% CI: 57.4–146.6) vs 74.3 min for transvaginal mesh-related complications (95% CI: 57.4–91.2; p = 0.07).

The average time from primary mesh repair to index surgery was 33.4 months (95% CI: 24.5–42.2). In the TVM group, this interval was 28.1 months (95% CI: 17.5–38.7) vs 46.3 months (95% CI: 30.2–62.5) in the SCP group (p = 0.06).

For the 83 reoperations, only one intraoperative complication occurred during reoperation, which was bladder injury during vaginal removal of an anterior mesh for vaginal exposure. Six postoperative complications were identified (7.2%): 2 infected hematomas (complete recovery after medical treatment), 3 vesicovaginal fistulas (resulting in 2 failures and 1 success with permanent morbidity), and 1 spondylodiscitis (recovery after antibiotics).

The mean follow-up after the last reoperation for a complication in our center was 41 months (95% CI: 34.3–47.7). One patient was withdrawn from follow-up after treatment of a vesicovaginal fistula, when carcinoma of the bladder neck was discovered. Figure 3 summarizes the outcome after reoperation. A total of 11 patients (15.9%) required more than one surgical procedure, with 8 undergoing two interventions (11.6%) and 3 undergoing three interventions (4.3%). The mean number of interventions performed to treat these 69 complications was 1.2 (95% CI: 1.1–1.3), with no statistically significant difference between the SCP and TVM groups (p = 0.3). By the end of our study period, excluding the patient treated for neoplasia, 53 patients (77.9%) were completely cured, 9 patients (13.2%) were improved, 1 patient (1.5%) was cured with permanent morbidity (continent urostomy), and the treatment failed in 5 patients (7.4%). Residual pain was reported by 11.8% of the patients overall and by 22.6% of patients who presented with pelvic pain or dyspareunia before index surgery.

During the same period (October 2006 to September 2014), 1,123 prolapse repair procedures were performed at Nîmes University Hospital’s gynecology or urology unit, by SCP in 525 cases and TVM in 598 cases. Thirty-two patients (2.8%) required reoperation for a mesh-related complication during the period, 7 following SCP and 25 following TVM placement, resulting in a reoperation rate for mesh-related complications of 1.3% after SCP and 4.2% after TVM.

Discussion

This series only included reoperations for mesh-related complications and not those with other causes, such as recurrent prolapse, de novo urinary incontinence, and complications related to the surgical procedure. Similarly, as mesh-related complications that did not require surgery were excluded, this is not an exhaustive survey of mesh-related complications. In a series of 347 patients with mesh-related complications published by Abbott et al. in 2014, surgical intervention was required in only 49% of cases [20]. A survey of surgically treated complications, however, offers the advantage of being objective and of addressing the severest complications. Table 5 lists the published series of reoperations for mesh-related complications. These were mainly small studies with often short patient follow-up after reoperation.

In line with the results published by other groups, the main mesh-related complication reported in our series was vaginal exposure. Two-thirds of the cases of vaginal exposure occurred in women who had undergone TVM repair. The exposure rates after TVM repair are highly variable, with reported frequencies of 3–20% [27, 28, 33–36] and a mean prevalence of 11.1 to 13.1% [7, 37]. The rate of mesh exposure after SCP is 2.2 to 3.4% on average [4, 7, 38]. According to several authors, the efficacy of medical therapy for TVM exposure is generally low, and surgical intervention is required when it fails [7, 27, 39]. Surgical first-line treatment of vaginal exposure is more frequent following SCP, owing to the risk of spondylodiscitis and the low efficacy rate of medical therapy [7]. Some authors reported very high efficacy with mesh removal for vaginal exposure [18, 22]. For both types of primary repair combined, surgical treatment of vaginal exposure using a vaginal approach in the vast majority of cases resulted in the complete resolution of symptoms in 87.9% of our patients. Mesh exposure is the main complication that required reoperation, but is also the one that is treated the most effectively.

In our series, 31 patients (44.9%) had pain before reoperation, but pain was the primary symptom in only 23 patients (33.3%). Pain appeared to be the main symptom of symptomatic mesh contraction in our series. Mesh contraction has been well described in the literature and can be responsible for dyspareunia and pelvic pain, in addition to voiding dysfunction [15, 35, 40]. Some authors have reported extremely high success rates with surgical treatment of mesh contraction, with symptom resolution in 100% of cases [15, 22]. These figures appear over-optimistic compared with our experience of certain patients in whom pain persists after removal of the mesh, possibly because of residual fibrosis. Although it is generally accepted that severe contraction can cause pain, a direct causal link between mesh and neuropathic pain may be more difficult to establish. In these situations, medical therapy with analgesics and possibly repeated nerve blocks has been proposed as both first-line therapy and a diagnostic test.

For all complications combined, residual pain or dyspareunia was reported by 11.8% of our patients, and by 22.6% of patients who had pain before index surgery. In the series of 84 reoperations for TVM-related complications described by Crosby et al., 51% of women still had pain, with a threefold risk of persistence of this pain compared with the group before complication surgery [22]. Other authors have highlighted the frequent presence of residual pain in this type of patient after mesh excision [13, 19, 41]. De novo pain or dyspareunia is known to occur, even in the absence of contraction or neuropathic pain, and requires medical therapy as the first-line treatment [42]. The prevalence of de novo dyspareunia has been estimated at 2.3% after SCP and 13.9% after transvaginal polypropylene mesh [38], but postoperative dyspareunia can also occur after surgery without the use of mesh [8]. Data on dyspareunia are not always available in the literature, especially for SCP [38], and in the absence of comparative randomized studies that highlight sexual function, the prevalence of this complication is difficult to ascertain.

Thus, pain syndrome can be a very serious complication after POP repair. Other severe complications were observed in our series such as fistulas, which have a very poor prognosis even after surgery. All these complications are rarer, but very difficult to treat. In total, for all the complications combined, 15.9% of patients in our series required several interventions at our hospital. This percentage is probably a slight overestimation because of selection bias, as the patients treated in a tertiary referral center are often those with the most severe complications. The number of patients requiring more than one intervention ranges from 8 to 46% in the literature, depending on the study (Table 5). Margulies et al. found that the median number of reoperations to achieve a satisfactory outcome is 2 [11]. We performed 45 partial mesh excisions as first-line management (65.2%), and only 9 of these patients required a second intervention (20%). Pelvic organ prolapse is known to recur more frequently after complete mesh removal than after partial excision (29 vs 5%) [16], which justifies conservative primary management where possible.

We described our complications using the Clavien–Dindo system [32] and the IUGA/ ICS classification [31]. The IUGA/ICS system is more recent and specifically for reconstructive pelvic surgery, with the aim of standardizing how mesh-related complications are described and recorded, to improve and facilitate comparisons of management strategies [31]. Because our study was retrospective and the site and size of exposure were not always recorded, some exposures could not be classified precisely. It would be helpful if this system were used when complications are first diagnosed. A recent retrospective evaluation by Batalden et al. on the use of the IUGA/ICS system in routine practice for vaginal exposure encountered the same limitations [43]. Furthermore, several patients in our study coded as 4B had very different complications: vesicovaginal fistula, mesh contraction with voiding dysfunction, and bladder extrusion. As other authors have already commented, it would be useful if this category were subdivided to distinguish between different types of complications [17]. Another limitation of this system mentioned by some authors is that the only symptom described is pain [17, 43]. Other complaints such as urgency or bleeding in particular, are often reported and may be the indication for surgery. Other limitations have been discussed in the literature, in particular, its failure to take into account certain signs of severity of the complication, such as the need for additional surgery, or bleeding severity [44]. Functional impact and patient satisfaction should also be taken into account [43, 44], although we feel that these variables would be difficult to incorporate into a system of this type.

Our study’s main limitation is its retrospective and single-center design. This study does not assess the morbidity of pelvic organ prolapse repair, but shows the types of mesh-related complications that require reoperation and provides insight into their management in a specialized center. Patients referred by other centers may have particularly serious complications, which would bias the results by inflating the number of reoperations required in addition to the postoperative sequelae. A survey of all the mesh surgeries performed in our center was also performed retrospectively. Many patients had not been seen since their 3-month review. We are currently re-contacting all the patients in this cohort to determine which ones received treatment elsewhere and to obtain a precise assessment of their functional symptoms and level of satisfaction, using standardized questionnaires. In addition, although the total study duration was 8 years, the follow-up period for some patients was too short for any complications to have been observed.

As regards our own experience, it is noteworthy that surgical treatment of mesh-related complications after POP repair accounted for about 7% of all pelvic floor surgery performed in our tertiary referral center during the study period. The overall rate of reoperation for a mesh-related complication during the study period was 4.2% after TVM placement and 1.3% after SCP. Nevertheless, our results must be considered with caution, because our study is not designed to compare mesh-related complications between the TVM group and the SCP group. The two groups are not similar at baseline, which makes any attempt to compare them debatable. These figures are somewhat lower than those identified in the literature for TVM repair [7, 37] and similar to the results of a retrospective, nonrandomized series published by de Landsheere et al., in which the total reoperation rate after placement of 524 Prolift© meshes was 11.6% after a median follow-up of 36 months, but only 3.6% when reoperations solely for mesh-related complications were considered [24]. More limited data are available for SCP: in a review of the literature, de Tayrac and Sentilhes reported a mean reoperation rate of 2.9% [7], but the complications were not all mesh-related.

This survey of mesh-related complications highlights the need for specialized training and knowledge of the risks associated with these interventions. As surgical techniques for pelvic organ support have become more commonplace, they are increasingly performed by inexperienced surgeons. This situation increases the risk of postoperative complications more likely caused by the surgical technique than the mesh itself [45, 46]. Lack of knowledge and experience can also result in the poor management of complications and increased morbidity [36, 46]. In line with other authors, we believe that better selection of patients and surgical indications, and improvement of surgical techniques are necessary to reduce mesh-related complications [45–48]. In addition, since the beginning of our study (2006), some mesh kits have been withdrawn from use, and the newer meshes introduced onto the market are lighter [8]. Although they have not been evaluated within a randomized study, a lower rate of complications (specifically mesh contraction) may be expected. The reoperation rates for mesh-related complications must be balanced against the efficacy of mesh placement compared with native tissue repair, especially for anterior compartment prolapse, in terms of prolapse recurrence [8, 47].

Conclusion

This series is one of the largest reported in the literature. It reflects our own experience and illustrates the variety of mesh-related complications and their management. The surgical procedures used, operating times, postoperative outcomes, and the number of surgical procedures required are precisely described, offering insight into the technical aspects of this type of surgery. We show that most mesh-related complications can be treated successfully by partial or total excision of the mesh, as 92.6% of the patients in our series were cured or significantly improved after surgery, but with “permanent morbidity” in 1.4% of cases.

Surgeons involved in the management of pelvic floor disorders must be aware of the specific risks associated with this type of surgery. Technical proficiency and knowledge of the risks are essential if complications are to be prevented. Training in new techniques must be encouraged, possibly with industry support. When complications occur, they must be recognized and reported to provide reliable, up-to-date public health data. For example, registers of mesh-related complications would provide precise complication rates for each type of mesh and surgical technique used. The classification systems currently available, especially the IUGA/ICS system, are still barely used outside of clinical research protocols, because of a number of shortcomings. Yet, reliable comparisons between surgeons and techniques require the use of such tools to better describe complications. Specialist centers should manage the most severe complications, because inappropriate treatment deprives women of the opportunity for recovery. The management strategy must be agreed through multidisciplinary team meetings, as cross-disciplinary expertise is essential for high-quality care. Patients must be fully informed before any surgery for pelvic organ prolapse, irrespective of the surgical approach and technique selected, because no surgery is completely risk-free.

In our experience, and bearing in mind the limitations already described, we estimate the reoperation rate for complications directly caused by mesh to be 4.2% after TVM repair and 1.3% after SCP. The most frequent complication identified was vaginal mesh exposures, the treatment of which is generally straightforward. Nevertheless, some of these complications are potentially serious and their management results in considerable tissue damage, which obviously raises many questions given that the underlying condition is benign and the sole aim of its surgical management is to improve the woman’s quality of life. Surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence has erroneously been regarded as “easy,” especially since the advent of TVM kits. As a result, it has too often been tackled by inexperienced surgeons, which has undoubtedly increased the incidence of preventable complications. As is often the case in the field of surgery, outcomes will improve through technological advances (better tolerated materials, more reproducible techniques, the development of innovative treatments such as cell culture), but will also require the designation of specialist centers (approved units, surgeons with recognized expertise, selected patients). In our opinion, abandoning the use of mesh in pelvic organ prolapse repair, in particular, transvaginal repair, is not the solution, but the utmost effort should be made to minimize strategic and technical errors: all new devices must be rigorously evaluated before being introduced on to the market, all surgeons must be prepared to question and improve their practices, and all patients must be aware of the anticipated benefits and risks of the treatments proposed.

References

Helström L, Nilsson B. Impact of vaginal surgery on sexuality and quality of life in women with urinary incontinence or genital descensus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84(1):79–84.

Swift SE. The distribution of pelvic organ support in a population of female subjects seen for routine gynecologic health care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(2):277–85.

Swift S, Woodman P, O’Boyle A, Kahn M, Valley M, Bland D, et al. Pelvic Organ Support Study (POSST): the distribution, clinical definition, and epidemiologic condition of pelvic organ support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(3):795–806.

Nygaard IE, McCreery R, Brubaker L, Connolly A, Cundiff G, Weber AM, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a comprehensive review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):805–23.

Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Brown J. Surgery for women with apical vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD012376.

Diwadkar GB, Barber MD, Feiner B, Maher C, Jelovsek JE. Complication and reoperation rates after apical vaginal prolapse surgical repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 1):367–73.

De Tayrac R, Sentilhes L. Complications of pelvic organ prolapse surgery and methods of prevention. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(11):1859–72.

Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Marjoribanks J. Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD012079.

Food Drug Administration FDA. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm262435.htm.

South MMT, Foster RT, Webster GD, Weidner AC, Amundsen CL. Surgical excision of eroded mesh after prior abdominal sacrocolpopexy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(6):615.e1–5.

Margulies RU, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Fenner DE, McGuire EJ, Clemens JQ, Delancey JOL. Complications requiring reoperation following vaginal mesh kit procedures for prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6):678.e1–4.

Ridgeway B, Walters MD, Paraiso MFR, Barber MD, McAchran SE, Goldman HB, et al. Early experience with mesh excision for adverse outcomes after transvaginal mesh placement using prolapse kits. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6):703.e1–7.

Hurtado EA, Appell RA. Management of complications arising from transvaginal mesh kit procedures: a tertiary referral center’s experience. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(1):11–7.

Marcus-Braun N, von Theobald P. Mesh removal following transvaginal mesh placement: a case series of 104 operations. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(4):423–30.

Feiner B, Maher C. Vaginal mesh contraction: definition, clinical presentation, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 Pt 1):325–30.

Tijdink MM, Vierhout ME, Heesakkers JP, Withagen MIJ. Surgical management of mesh-related complications after prior pelvic floor reconstructive surgery with mesh. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(11):1395–404.

Skala C, Renezeder K, Albrich S, Puhl A, Laterza RM, Naumann G, et al. The IUGA/ICS classification of complications of prosthesis and graft insertion: a comparative experience in incontinence and prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(11):1429–35.

Firoozi F, Ingber MS, Moore CK, Vasavada SP, Rackley RR, Goldman HB. Purely transvaginal/perineal management of complications from commercial prolapse kits using a new prostheses/grafts complication classification system. J Urol. 2012;187(5):1674–9.

Lee D, Dillon B, Lemack G, Gomelsky A, Zimmern P. Transvaginal mesh kits—how “serious” are the complications and are they reversible? Urology. 2013;81(1):43–8.

Abbott S, Unger CA, Evans JM, Jallad K, Mishra K, Karram MM, et al. Evaluation and management of complications from synthetic mesh after pelvic reconstructive surgery: a multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(2):163.e1–8.

Arsene E, Giraudet G, Lucot J-P, Rubod C, Cosson M. Sacral colpopexy: long-term mesh complications requiring reoperation(s). Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(3):353–8.

Crosby EC, Abernethy M, Berger MB, DeLancey JO, Fenner DE, Morgan DM. Symptom resolution after operative management of complications from transvaginal mesh. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(1):134–9.

Withagen MI, Vierhout ME, Hendriks JC, Kluivers KB, Milani AL. Risk factors for exposure, pain, and dyspareunia after tension-free vaginal mesh procedure. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):629–36.

De Landsheere L, Ismail S, Lucot J-P, Deken V, Foidart J-M, Cosson M. Surgical intervention after transvaginal Prolift mesh repair: retrospective single-center study including 524 patients with 3 years’ median follow-up. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(1):83.e1–7.

Quemener J, Joutel N, Lucot J-P, Giraudet G, Collinet P, Rubod C, et al. Rate of re-interventions after transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair using partially absorbable mesh: 20 months median follow-up outcomes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;175:194–8.

Belot F, Collinet P, Debodinance P, Ha Duc E, Lucot J-P, Cosson M. Risk factors for prosthesis exposure in treatment of genital prolapse via the vaginal approach. Gynécologie Obstétrique Fertil. 2005;33(12):970–4.

Collinet P, Belot F, Debodinance P, Ha Duc E, Lucot J-P, Cosson M. Transvaginal mesh technique for pelvic organ prolapse repair: mesh exposure management and risk factors. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17(4):315–20.

Deffieux X, de Tayrac R, Huel C, Bottero J, Gervaise A, Bonnet K, et al. Vaginal mesh erosion after transvaginal repair of cystocele using Gynemesh or Gynemesh-Soft in 138 women: a comparative study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(1):73–9.

Chanelles O, Poncelet C. Late vaginal mesh exposure after prolapse repair. J Gynécologie Obstétrique Biol Reprod. 2010;39(8):672–4.

Miklos JR, Chinthakanan O, Moore RD, Mitchell GK, Favors S, Karp DR, et al. The IUGA/ICS classification of synthetic mesh complications in female pelvic floor reconstructive surgery: a multicenter study. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(6):933–8.

Haylen BT, Freeman RM,Swift SE, Cosson M, Davila GW, Deprest J, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint terminology and classification of the complications related directly to the insertion of prostheses (meshes, implants, tapes) & grafts in female pelvic floor surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(1):3–15.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P-A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–13.

Abdel-Fattah M, Ramsay I, West of Scotland Study Group. Retrospective multicentre study of the new minimally invasive mesh repair devices for pelvic organ prolapse. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;115(1):22–30.

Fatton B, Amblard J, Debodinance P, Cosson M, Jacquetin B. Transvaginal repair of genital prolapse: preliminary results of a new tension-free vaginal mesh (Prolift technique)—a case series multicentric study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(7):743–52.

Gauruder-Burmester A, Koutouzidou P, Rohne J, Gronewold M, Tunn R. Follow-up after polypropylene mesh repair of anterior and posterior compartments in patients with recurrent prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(9):1059–64.

Kasyan G, Abramyan K, Popov AA, Gvozdev M, Pushkar D. Mesh-related and intraoperative complications of pelvic organ prolapse repair. Cent Eur J Urol. 2014;67(3):296–301.

Deffieux X, Sentilhes L, Savary D, Letouzey V, Marcelli M, Mares P, et al. Indications of mesh in surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse by vaginal route: expert consensus from the French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). J Gynécologie Obstétrique Biol Reprod. 2013;42(7):628–38.

Deffieux X, Letouzey V, Savary D, Sentilhes L, Agostini A, Mares P, et al. Prevention of complications related to the use of prosthetic meshes in prolapse surgery: guidelines for clinical practice. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;165(2):170–80.

Deffieux X, Huel C, de Tayrac R, Bottero J, Porcher R, Gervaise A, et al. Vaginal mesh extrusion after transvaginal repair of cystocele using a prosthetic mesh: Treatment and functional outcomes. J Gynécologie Obstétrique Biol Reprod. 2006;35(7):678–84.

Maher CF, Qatawneh AM, Dwyer PL, Carey MP, Cornish A, Schluter PJ. Abdominal sacral colpopexy or vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy for vaginal vault prolapse: a prospective randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(1):20–6.

Blandon RE, Gebhart JB, Trabuco EC, Klingele CJ. Complications from vaginally placed mesh in pelvic reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(5):523–31.

Gyang AN, Feranec JB, Patel RC, Lamvu GM. Managing chronic pelvic pain following reconstructive pelvic surgery with transvaginal mesh. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(3):313–8.

Batalden RP, Weinstein MM, Foust-Wright C, Alperin M, Wakamatsu MM, Pulliam SJ. Clinical application of IUGA/ICS classification system for mesh erosion. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;35(5):589–94.

Bontje HF, van de Pol G, van der Zaag-Loonen HJ, Spaans WA. Follow-up of mesh complications using the IUGA/ICS category-time-site coding classification. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(6):817–22.

Bako A, Dhar R. Review of synthetic mesh-related complications in pelvic floor reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(1):103–11.

Jacquetin B, Cosson M. Complications of vaginal mesh: our experience. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(8):893–6.

Swift S. To mesh or not to mesh? That is the question. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(5):505–6.

De Ridder D. Should we use meshes in the management of vaginal prolapse? Curr Opin Urol. 2008;18(4):377–82.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

S. Warembourg and M. Labaki declare that they have no conflicts of interest. B. Fatton declares acceptance of paid travel expenses from Boston Scientific and declares being a consultant for Allergan and Astellas. R. de Tayrac declares acceptance of paid travel expenses, payment for research, and being a consultant for Boston Scientific. P. Costa declares acceptance of paid travel expenses and being a consultant for Allergan and Boston Scientific.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Warembourg, S., Labaki, M., de Tayrac, R. et al. Reoperations for mesh-related complications after pelvic organ prolapse repair: 8-year experience at a tertiary referral center. Int Urogynecol J 28, 1139–1151 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3256-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3256-5