Abstract

In this paper, we investigate the impact of local quality of government on regional attractiveness to migrants inferred from individual revealed preferences and net migration. The analysis is based on panel data estimations of 254 European regions for the period between 1995 and 2009. Different instrumental variable techniques have been employed in order to assess the extent to which differences in local government quality affect preference rankings for different locations and to account for potential endogeneity concerns. The results point towards an important influence of specific factors related to the regional quality of government, such as the fight against corruption or government effectiveness, on the ability of European regions to position themselves as attractive places for future residents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Understanding the causes of regional population change has attracted the interest not only of academics, but also of policy-makers. This is because population change has of late been stuck in a ‘jobs versus people’ debate—i.e. the question of whether people follow jobs and hence firms, or whether quality-of-life-related factors determine people’s location decisions, with firms and jobs following suit (Partridge and Rickman 2003, 2006). Most explanations have traditionally relied heavily on differences in regional economic strength, mainly in the form of expected income and living standards, as the main motivation for population mobility (Hicks 1932; Harris and Todaro 1970). More recently—and despite the fact that money and jobs have remained at the heart of many theories—scholars have increasingly focused on differences in non-pecuniary attributes, such as place-based natural or man-made amenities (Partridge and Rickman 2003, 2006; Ferguson et al. 2007; Rodríguez-Pose and Ketterer 2012), as key factors behind population growth and decline.Footnote 1 In addition, social capital, networks, and market access have also featured prominently as potential determinants of population change (Davis et al. 2002; McKenzie and Rapoport 2007).

One factor which has been generally overlooked in the literature has been that of the quality of the institutions, in general, and that of government quality, in particular. There is much more on the impact of government institutions on economic development and growth than on population differences. This is not surprising as the definition and role of government institutions has been and remains controversial, and the measurement of government quality is fraught with problems. Moreover, the perception of the quality of government in areas of destination by would-be movers may be considered as much weaker than that of the availability of jobs or the wealth of the place.

In this paper, we aim to overcome this gap in the literature by drawing attention to the influence of quality of government on the attractiveness of a given region for migrants. In particular, we investigate the impact of a set of different government quality parameters—level of corruption, government effectiveness, government accountability, and rule of law—on preference rankings for different locations using Tiebout’s (1956) approach where people ‘vote with their feet’, at a sub-national regional level in Europe.

Our analysis hence aims to provide a greater understanding about how the quality of the government shapes the attractiveness of a region, and hence its capacity to lure future residents. The analysis contributes to the existing literature on the link between local government quality and sub-national urban or regional outcomes by providing evidence that population migration is not based on atomistic responses to economic or environmental aspects, but tends to be shaped and embedded in societal rules and norms. We use a novel data set of institutional quality at a NUTS-2—nomenclature of territorial statistical units—regional level in order to evaluate the relevance of local government aspects on a territory’s attractiveness. The analysis covers 254 European regions for the period between 1995 and 2009.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. We first review the relevant literature in Sect. 2, before developing a simple conceptual framework of regional attractiveness based on people’s revealed preferences using Tiebout’s ‘voting with feet’ approach (Sect. 3). Section 4 presents a discussion of the data, the empirical strategy chosen, and addresses potential endogeneity concerns. In Sect. 5, we introduce and interpret the regression results using a variety of different estimators. Section 6 concludes.

2 Government institutions and voting with feet

Institutions matter for economic development (e.g. Acemoglu and Johnson 2005); and, as highlighted by a strand of recent literature, population change represents a basic transmission channel between institutions and economic development. Acemoglu and Johnson (2005), for instance, consider colonial migration as essential for the design of the local institutions which shape economic performance. Beine and Sekkat (2013) and Docquier et al. (2010), also provide country-level evidence about how population change leads to institutional change. Network effects may increase the source country’s exposure to different social and political norms (Spilimbergo 2009), and the institutional changes linked to population growth or migration may be very long-term (Rodríguez-Pose and Berlepsch 2014, 2015). However, how local institutions directly affect population patterns and the attractiveness of potential destinations has been a question which has been largely neglected in the literature.

In this paper, we aim to fill in this gap by examining the role of government quality for regional attractiveness and sub-national population change. We precisely want to assess how the quality of local government affects regional preference rankings, and hence the ability of regions to attract future residents. As indicated, the empirical evidence of the role of government quality as a potential driver of decisions to relocate is very scarce. There are a few exceptions. Some studies have highlighted that migrants judge how institutional conditions of the area of destination may play a fundamental role in future lifetime earnings (Ghatak and Levine 1993). This has been the case when analysing the dimension of discrepancies in terms of institutional quality in the context of the nineteenth century mass migration movements. Bertocchi and Strozzi (2008), for instance, conclude that nineteenth century institutions made an important difference in the attractiveness of destinations for a sample of selected Old and New World countries. Rotte and Vogler (2000), when considering the impact of political stability in the countries of origin on migration flows to Germany, also found empirical support for the fact that political instability and terror in the countries of origin act as significant push factors. From a more theoretical perspective, it has also been posited that the availability of a mix of public goods, including high-quality institutions, public education, and ‘law and order’ aspects, has been essential to making mainly rich economies attractive to new residents (Pritchett 2006; Voretz 2006).

Similarly, from a more place-based regional perspective, the scholarly literature has tended to stress that institutional and historical factors are focal territorial assets enhancing the appeal of places and influencing the ‘positioning’ of regions vis-á-vis each other (Deas and Giordano 2001; Malecki 2004; Camagni and Cappello 2009). From this perspective, local institutional settings and government quality may amount to a crucial aspect mobilising a region’s assets by creating the right incentives, promoting private sector development, as well as the participation of citizens in society and decision-making processes. Empirical evidence supporting the role of government quality indicators in a place-based regional context tends to be, however, rather limited. Some of the literature has focused on the specific provision of public goods and services, such as social welfare spending in the areas of origin and destination. Day (1992), for example, uncovered that population change across Canadian provinces is affected by the varying levels of social expenditure by provincial governments and by the dimension of unemployment insurance and transfer payments directed to individuals. However, the majority of this type of research has been concerned with population change in areas with high levels of social expenditure (e.g. Bode and Zwing 1998). Local political leadership has also been the object of attention. Greasley et al. (2011) analysed whether the leadership capacity of local government has affected population change in 56 urban areas in England. They found that more consolidated governance structures are weakly linked to greater population growth.

3 Conceptual framework

However, the majority of the contributions presented in the previous section, while important, have either been tangential to, or only scratched the surface of the complex relationship between quality of government and revealed locational preferences. In this section, we intend to overcome this deficit by modelling the relationship between the institutional environment, shaping the quality of local governments, and regional locational preferences. Given the difficulties to capture the multi-dimensional nature of place-based satisfaction when using a single metric indicator, we resort to an analysis based on the assumption that economic agents reveal their locational preferences by ‘voting with their feet’ (Tiebout 1956). This modelling strategy relies on individuals’ own satisfaction readings, evaluating current and/or future locational preferences of migrants across a range of different locations. Following Faggian et al. (2007), Ferguson et al. (2007), and Partridge (2010), we argue that persistent net migration rates would consequently reveal which territories are, on average, associated with a higher preference ranking and may thus be correlated with a higher and possibly more ‘objective’ assessment of regional attractiveness.Footnote 2 This hedonic self-assessment approach implies that regional population change may be a suitable predictor of citizens’ actual preferences rankings.

When conceptualising regional locational preferences, we rely on a set of simple assumptions and explain net migration through households’ and firms’ responses to spatially differing economic efficiency and site-specific non-economic attributes, allowing for Tiebout’s (1956) grouping of heterogeneous households into more homogenous subgroups. We assume that firms’ prime behavioural criterion is profit maximisation, contrasting and comparing regional output and land prices, as well as wages and site-specific attributes such as market access, or the quality of public services. If a particular territory i has been found to offer larger potential profits than any other potential location, then firms are likely to relocate, or expand to region i increasing labour demand, and hence job opportunities.

Furthermore, we assume that households’ utility maximisation represents their prime behavioural criterion and that individuals take the economic (i.e. income-related), as well as the non-economic benefits of different locations into consideration. Furthermore, households are also assumed to rank different locations according to their place-specific expected utility values and to compare the resulting net benefits across all possible locations i. Following Ferguson et al. (2007), net migration into region i may hence be described as:Footnote 3

where \(V_{i}-V_{\mathrm{nat}}\) reflects the indirect utility derived from residing in region i relative to the national average (or alternative locations), and \(M_{\mathrm{avg}}\) denotes the average moving costs when changing the place of residence. Based on the discussion above, people’s incentives to ‘vote with their feet’ are likely to be sensitive to an array of specific territorial attributes which determine the average utility of places, and may be interpreted as a form of revealed preference ranking across different locations. Using a more dynamic perspective when analysing households’ and firms’ behaviour in a spatial equilibrium approach, we allow for labour demand and supply shocks, opening up the possibility of studying how regions adjust when out of equilibrium. This offers a Tiebout-type consistent way of measuring regional attractiveness based on net utility maximisation.

We hypothesise that specific local features (such as income, unemployment, or demographic aspects) represent an adequate proxy measure for an average individual’s access to economic, as well as non-economic, location-specific characteristics. As a result, we model households’ location-specific utility as determined by both economic and non-economic attributes. We proxy location-specific expectations of future income and economic benefits with regional unemployment ratios (Puhani 2001) and, following Ferguson et al. (2007), we model traditional economic drivers in differences with respect to all other possible locations i. The alternative non-economic characteristics include regional factors such as network effects, human capital-related, and ‘society or government embedded’ institutional elements, such as the quality of local government structures—our main variable of interest.

The quality of local institutions is introduced in our model by means of four individual indicators of regional government quality. We assume that the quality of a territory’s political and government institutions represents an important factor in shaping locational preferences, all else being equal. In particular, we focus on four elements: corruption, government efficiency, rule of law, and government accountability. The level of corruption in a territory has important financial and non-financial implications. Low levels of corruption and efficient government bureaucracies contribute not only to reduce uncertainty and the monetary costs of economic activity, but also to increase the predictability of business transactions and to enhance the residents’ perception of a service-oriented local government and of equal treatment. The presence of a government which generally eschews graft and does not use public authority for private gain may appeal to migrants from more corrupt areas. Similarly, the quality of officials and of the civil service, the credibility of a government, and the effectiveness of its policies may influence relocation decisions. The presence of legally embedded norms and rules in local societies and confidence in the enforcement of legal rights can be regarded as another important pull factor for migrants. Migrants will be attracted by territories where contracts are enforced, property rights safeguarded, and where the police and the courts can be trusted—in sum, by areas characterised by a strong rule of law. A strong rule of law will be linked not only to increased pecuniary benefits for individuals, but also to improvements in the quality of life. Finally, the capacity to participate in decision-making, by either electing governments or by exercising basic democratic freedoms, such as the freedom of expression or association will affect the appeal of places towards future residents. A more democratic local environment where residents have a voice and the ability to participate in the political process, in shaping and deciding local policies and taxation systems, and where governments are accountable to their voters for their actions, may positively affect citizens’ decisions to move, and may even entail further material and immaterial benefits in the form of greater equality.

The control parameters can also be embedded in the conceptual framework by means of a vector which includes some of the key non-institutional factors which may shape the perception of territories’ attractiveness. One of these is the share of labour employed in agriculture. More agricultural societies have traditionally been linked to backwardness and higher rates of emigration (Caselli and Coleman 2001), although in a context of relative poverty, a large agricultural labour share may also act as a poverty constraint to out-migration, in particular in the early stages of development. The demographic composition of the population is another component of the control vector. It has also been highlighted by the literature as a notable driver of mobility (Massey et al. 1993; Zimmermann 2005). Young individuals are much more likely to ‘vote with their feet’. Another potential determinant of migration is the presence of man-made or natural amenities. Urban amenities and quality-of-life aspects have featured increasingly prominently in migration studies (e.g. Partridge and Rickman 2003; Ferguson et al. 2007; McGranahan 2008; Partridge 2010, for the US and Rodríguez-Pose and Ketterer 2012, for the EU) and highlight the potential of the natural environment, pleasant climatic characteristics, or the vibrancy of a region’s cultural context to attract future residents. In addition, the presence of groups from the same geographical origin in any given region will facilitate integration by members of those communities and an easier access to jobs, while lowering the assimilation costs in new cultural and socio-political structures (Massey et al. 1993, 1998). This network effect may trigger path dependence and significantly contribute to the perceived attractiveness across different places, influencing current and/or future place-specific utility readings reflecting potential chain migration effects at the ethnic group, village, or even family level. Finally, it may also be argued that regional and location-specific conditions are affected by the capacity of surrounding regions to attract people, with a stronger spatial dependence for regions located next to each other than for those at a greater distance. We take this possibility into account by specifying a weight matrix providing information on the connectivity between the considered NUTS-2 territories, and use this information to construct a spatially lagged dependent variable, which we include in some of our empirical specifications.Footnote 4

4 Empirical analysis

4.1 Data

The exact definition and sources of the variables included in our empirical analysis are summarised in Appendix Table 5. We use a data set that covers 254 NUTS-2 regions in the European Union (EU) for the period from 1995 to 2009. Our dependent variable is regional net migration rates, and—as indicated in Eq. (2) below—our independent variables of interest are different proxies for the local quality of government, complemented by a series of controls which reflect the traditional determinants of the attractiveness of a territory.

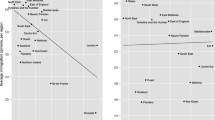

The data stem from different sources. Our quality of government variables at NUTS-2 level are extracted from the quality of government data set developed by Charron et al. (2014). This data set—sharing a similar conceptual base with the World Bank’s country-level ‘World Governance Indicators’ (WGI) (Kaufmann et al. 2009)—is built on an EU-wide regional survey of 34,000 individuals.Footnote 5 The authors use 16 of the questions in the survey in order to elaborate regional-level indices of local (1) corruption, (2) rule of law, (3) regional bureaucratic (i.e. government) effectiveness, and (4) strength of democracy and electoral institutions (i.e. voice and accountability). These four dimensions are also combined in a single composite index of government quality (see Appendix Fig. 1) (see Charron et al. 2014 for an overview of the method). The results of the survey are then standardised and blended with the national-level World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) in order to generate a dynamic panel covering the period between 1995 and 2009.

The European Quality of Government Index (QoG). Source: Charron et al. (2014)

Most of the control variables stem from the Eurostat Regio database. These include unemployment rates, the ratio of people employed in agriculture, and the share of young population. We also use Eurostat in order to calculate the lagged migration rate, which is introduced as a measure for past migration. The information on the geographical coordinates of the NUTS-2 regions stems from Eurostat/GISCO.

A selection of natural amenity variables is also considered in the analysis. These refer to climate and/or physical landscape conditions.Footnote 6 The variables include information on environment-related attributes, such as whether a region has access to the sea or is landlocked, and on climate-related characteristics (i.e. precipitation, temperature, cloudiness in January and July). The climate amenity variables stem from Mitchell et al. (2004) and are measured as 30-year averages and introduced in the analysis as time-invariant regressors.

Our final set of variables is of a historical nature. They are used as instruments in order to assess potential endogeneity. The historical data set from which the data stem was gathered by Gilles Duraton, Giordano Mion, and Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, mostly by digitalising and geo-coding a series of historical maps provided by Kishlansky et al. (2003) and the online source www.euratlas.com. The historical variables include a number of indicators detailing the historical heritage of the regions of the EU. The reason for including historical variables as instruments is related to the fact that current institutions and, consequently, current quality of government derive from historical factors that have shaped and continue to shape the characteristics of territories (North 1990). As such, historical variables have frequently been used in the economics literature as instruments for the quality of local institutions (e.g. Porta et al. 1999; Acemoglu et al. 2001; Engerman and Sokoloff 2000). We can therefore expect a correlation with our independent variable of interest, but not with the error term.

4.2 Econometric specification

In line with the conceptual framework set out in Sect. 3, our aim is to estimate the determinants of preference rankings across different locations with respect to local government quality indicators. Using net migration, we also control for the traditional economic as well as for alternative location-specific factors. Based on Eq. (1), and on this the conceptual framework set out in Sect. 3, migration is a factor of:

where \(\hbox {mig}_{{it}}\) is the net migration rate in NUTS-2 region i in period t (with \(i=1,\ldots , 254\) and \(t=1,\ldots ,15\)).Footnote 7 \(\hbox {Econ}_{{it}}\) denotes a vector referring to regional economic strength in the form of local unemployment ratios. The government quality parameter (gov.quality) denotes a set of indices measuring different government-related institutional characteristics, while the set of control variables includes regional demographic components, such as the share of young population and of those working in the agricultural sector, and the lagged dependent variable as a potential indicator for network effects. The natural amenities are included in a reduced sample of our data set (see Sect. 5.3).

In our first estimation, we employ a fixed-effects panel data estimation strategy with heteroskedasticity robust standard errors clustered at the NUTS-2 level. Clustering the standard errors at the NUTS-2 level controls for serial correlation and group-wise heteroskedasticity. The advantage of using panel data estimation is that it enables us to control for unobservable variables that are region-specific and which may bias the results when omitted. Using fixed-effect therefore renders the results robust to region-specific time-invariant parameters. In order to control for shocks that affect all EU regions, we also include time dummies in all model specifications.Footnote 8

Our conceptual framework and past literature on regional preferences lead us to formulate a number of hypotheses regarding the association of the different parameters included in Eq. (2) and regional population change in the EU. We expect that factors such as the regional unemployment and the share of young population will be negatively connected to the pull of regions. The impact of the agricultural share is expected to be ambiguous, as, on the one hand, high employment in agriculture may represent a constraint to ‘people voting with their feet’ in relatively poor territories, but, on the other, it may also be a push factor. As the association of agricultural employment with a certain population change may be affected by the demographic structure of the population, we also interact agricultural employment with the proportion of young people, a variable for which we expect a positive coefficient.

The presence of non-native communities is accounted for by including the lagged dependent variable as an additional regressor. We anticipate that the presence of previous migrants will exert a positive influence on the locational attractiveness towards new residents. The presence of local cultural and natural amenities is also likely to enhance the attractiveness of places of destination. Finally, regarding our independent variables of interest, we envisage that regions with a better government—i.e. lower corruption, better rule of law, and more efficient, transparent, and accountable governments—are more attractive to migrants.

4.3 Instrumentation strategy

When examining individual revealed preferences as an indicator for a region’s overall preference ranking, potential endogeneity concerns affecting most economic and non-economic regressors, which may themselves be shaped by population growth or decline, need to be taken into account. We therefore adopt a two-pronged strategy. First, we introduce all explanatory variables with a 1 year lag and, second, we use instrumental variables (IV) regressions, with a special focus on our institutional variables.

The potential endogeneity of institutions involving different aspects of the political system, democracy, or government quality in general, has been the subject of many studies. Most of these analyses are concerned with economic growth as dependent variable (e.g. Barro 1999). In the context of population change and regional well-being, political and government quality-related institutions may give rise to potential reverse causality concerns, as new residents may drive local political or institutional changes affecting local politics and potentially how local governments respond to population growth-specific challenges. To control for these reverse causality issues, we instrument local government efficiency, as well as voice and accountability indicators, with past values. We argue that the local political structure is likely to be linked to the current political framework, but should not impact on current relocation decisions. A region’s corruption level or the rule of law could also under certain circumstances turn out to be endogenous. Local governments may, in principle, respond to population change or migration by selecting the extent to which they enforce the law, affecting the citizens’ perceptions of the government’s fight against corruption and their ability to trust the local police force or judicial system. We therefore run fixed-effects IV regressions in which the rule of law and corruption indicators are instrumented with past or initial values, again assuming that past institutional features are linked to current ones, but not to relocating decisions today.

In line with the institutional growth literature, we additionally run 2SLS IV regressions using a set of regional historical variables as instruments for the regional quality of government parameters considered. Four such variables are taken into consideration. The first variable (Charlemagne) determines whether a region belonged to Charlemagne’s empire. It takes the value 1 if the respective NUTS-2 region was part of the empire and/or represented a tributary territory at the time of the emperor’s death. A second variable (Rome) aims to proxy exposure by a region to Roman culture and its legal and military system. It measures whether a region belonged to the Roman Empire under Caesar (in 49 BC). Early Christianity is an indicator of whether a region was Christianised by around 600 AD. Finally, we also include a variable from the same source measuring the number of kingdom changes in any given region in the early Middle Ages. This variable is intended to provide a proxy for early political instability. The variable was built using several sources showing the boundaries of European kingdoms, based on ethnic origin, over the time period 500 AD–1000 AD in 100-year intervals. Every region in each of the six time periods is then earmarked by a certain kingdom using geo-coding techniques. The final variable measures the number of times a NUTS-2 region belonged to a different kingdom.

A region’s early exposure to royal and/or imperial rule or to the sphere of influence of the Church—meaning also a greater or lower exposure to local or centrally designed administrative, legal, moral, or military-related norms, standards, and requirements—may have crucially shaped informal norms and institutions, influencing, in turn, current levels of government quality. Conversely, a legacy of political instability, caused by constant switches in kingdoms and allegiances, could have also left a trace in the relationship between government and citizens.

5 Regression results

In this section, we present and interpret the regression results based on different estimation techniques. We first report the findings when applying the panel data fixed-effects method to Eq. (2), followed by alternative estimation methods—i.e. fixed-effect instrumental variables techniques, 2SLS regressions, and an Arellano-Bond GMM estimator, to take into account potential endogeneity concerns.Footnote 9

5.1 Fixed-effect panel estimations

Table 1 reports the regression results of estimating Eq. (2) using fixed-effect panel data estimation techniques on each measure of institutional quality introduced successively in the analysis. We first discuss the findings for the control variables, before turning to our independent variables of interest: the local government quality parameters.

Regarding the control variables, all columns in Table 1 show negative and in most specifications statistically significant coefficients for regional unemployment. High unemployment rates act, as indicated in previous literature, as a powerful deterrent for migration. Similarly, agricultural employment displays significant negative coefficients in all model specifications, suggesting a low appeal of predominantly rural regions, coupled with a potentially larger population decline in less industrialised areas. By contrast, regions with a younger demographic structure seem to act as a magnet for new residents, as all the coefficients are positive and significant (Table 1), although endogeneity concerns cast some shadows over this specific result. The interaction term between the agricultural employment and the demographic structure variable has in all specifications a significant negative connection to population changes, while migration network effects, proxied by the introduction of the lagged dependent variable as a regressor, suggest a persistent positive influence of the presence of past movers on current relocating decisions, pointing to the importance of network linkages stretching from home to host region.

The government quality variable coefficients stress the influence of this type of institutional variables on perceived regional attractiveness. The coefficient for the composite index of regional government quality (Column 3) is highly significant positive. This important role of government quality for people’s ‘voting with their feet’ behaviour is reproduced when the composite index is divided into its constituent components. In particular, local government effectiveness and low levels of corruption play an important part in shaping the attractiveness of places (Columns 4 and 5). By contrast, the coefficients for the confidence in the enforcement of legal rights, the general trust in the police and judicial system (Column 7), as well as the extent to which citizens may participate in the political process, voice their concerns, and value the accountability of their local government (Column 6) are positive, but not significant. Overall, these results point towards the absence of graft and the limitation of private interests when exercising public power, coupled with a good quality of public services and effective policy design and implementation as key elements in the attractiveness of European regions.

5.2 Endogeneity and panel instrumental variable (IV) estimations

We address potential endogeneity concerns in the fixed-effects analysis by means of two-stage least squares, as well as system-GMM instrumental variable techniques.

Table 2 reports the second-stage results for the panel data IV regressions using fixed effects. The first-stage regression results are displayed in Appendix Table 6.Footnote 10 The results confirm the negative impact of local unemployment rates and of local agricultural employment shares. The coefficient for the share of young residents, by contrast, changes signs in most specifications of the instrumental variable models. It is negative in all regressions and, with the exception of regression 2, always significant. This suggests a higher relocation propensity for the young, as well as reflecting the role of relocation as a potential life-time investment decision. The agricultural employment and demographic structure interaction parameter displays a positive coefficient, significant at the 10 % threshold level in most specifications (Table 2). The positive impact of this variable may thus be interpreted as an indication for a potential relocation poverty constraint depending on a region’s agricultural and demographic composition—i.e. the propensity to move out of less developed areas may be enhanced by demographic pressures on the land by a young population. The positive influence of relocation network effects on the regional appeal of NUTS-2 regions is confirmed in the instrumental variable regressions, again suggesting path dependency.

In Columns (3)–(7) of Table 2, we examine the impact of government quality. The coefficients confirm the results reported in Table 1. All government quality coefficients are positive. Once again, the coefficients are significant for control of corruption (Column 4) and government effectiveness (Column 5), but not for government accountability (Column 6), and the local rule of law (Column 7). Good governance, the reduction in uncertainty for economic transactions, an effective and interest-free use of public power, as well as the quality of public policies and services contribute to determine the ability of people to ‘vote with their feet’ and hence reveal their location preferences across Europe’s NUTS-2 regions.

In order to assess the validity of our instrumental variable estimations and to test the quality of our instruments, we perform a series of tests. First, we conduct the Anderson–Rubin test for weak instruments. As demonstrated at the bottom of Table 2, the Anderson–Rubin test shows that the null hypothesis of joint insignificance of the excluded instruments is rejected at 1 % in all model specifications. Moreover, the first-stage F tests of jointly insignificant instruments are rejected in all first-stage regressions and report for each model specification an F test statistic which is by far larger than ten. Finally, we also perform individual endogeneity test on the institutional variables. The test results displayed at the bottom of Table 2, indicate that endogeneity tends to be less of a concern for the institutional parameters, except for the effectiveness and the general quality of government index, which are characterised by p values of 0.024 and 0.014, respectively.

5.3 Two-stage least-squared (2SLS) and IV system–GMM estimations

As an additional robustness test and to further control for potential endogeneity, we consider alternative IV estimation techniques. As there are risks related to the sole use of initial or past values as instruments, we estimate another set of IV regressions, instrumenting our quality of government variables by a selection of time-invariant historical parameters. Due to limited data availability when using these historical components, the estimation results in this section are based exclusively on the NUTS-2 regions of the EU-15.

Table 3 and Appendix Table 7 report the estimation results when using 2-SLS regression techniques. Table 3 presents the second-stage regressions, while the first-stage regressions are reported in Appendix Table 7. The results for the standard relocation determinants point to a highly significant impact of local unemployment ratios and a persistently negative, although, not always significant, influence of regional agricultural employment shares. The regional demographic structure seems to affect the pull of regions to migrants—when measured by net migration rates—positively and demonstrates the attractiveness of a dynamic and young population composition in the EU-15.Footnote 11 Past migration movements, measured by the lagged dependent variable, are also statistically highly significant and display positive parameter estimates in all model specifications.

Using the additional set of historical instrumental variables for our institutional parameters by and large confirms the relevance of the government quality indices and highlights the positive impact of most institutional components. Low levels of corruption and government efficiency remain, once again, statistically significant, underlining the robustness of absence of graft and sound public policies as key determinants for migration. The coefficients for local rule of law and government accountability are, for the third time, statistically not significant when introduced as the only government quality indicators. Including all four quality of government parameters together (Table 3, Column 9) confirms the importance of low levels of corruption and high government effectiveness as a draw for new residents.Footnote 12 The robustness of these and previous findings is also reinforced when accounting for the potential effect of spatially lagged dependent variable (Table 3, Columns 8 and 10), with the respective parameter estimate of spatial weights showing positive coefficients which are, however, only weakly statistically significant in specification (10). Finally, when controlling for a set of physical amenity variables, the general quality of government index displays a highly significant positive coefficient on regional population growth (Columns 11 and 12). Physical amenities—such as blue winter skies and mild, but sunny summers—also entice new residents to specific European regions (Rodríguez-Pose and Ketterer 2012).

The general validity of the instruments used in the analysis is illustrated by the statistics reported at the bottom of Table 3. The p value test results of the Hansen J-statistics for over-identification restrictions show a strong rejection of the null hypothesis of joint insignificance, while the Anderson–Rubin statistics for weak instruments indicate that the null hypothesis is rejected at the 1 % threshold in all model specifications. This further corroborates the validity of the instruments. Finally, the first-stage regression results reported in Appendix Table 7, show that several of the historical variables considered are correlated—depending on the precise institutional component—with current levels of regional government quality.

We use dynamic panel regression techniques as our final robustness test. We choose a system-GMM estimator, as it enables us to account for unobservable heterogeneity and to control for endogeneity and for the persistency of explanatory variables (Bond et al. 2001). The regression results of the Arellano–Bond system–GMM estimations are reported in Table 4. They validate the findings of the 2SLS regressions, showing a significant positive impact of the corruption, government effectiveness, and general quality of government variables on population trends.Footnote 13

In brief, the results of the analysis indicate that government quality matters for regional appeal and hence for sub-national regional population change and may amount to an important regional pull factor for future residents. Along with economic and demographic characteristics, population changes are also affected by local institutional conditions. Better local quality of government affects location-specific preference rankings and may help people to ‘vote with their feet’. The analysis further reveals that low corruption and government effectiveness are the most important quality of government dimensions determining a region’s attractiveness to new residents. Finally, the potential response of institutional settings to the presence of past movers or increasing local population, does not affect our findings, as shown by the range of instrumental variable regressions used.

6 Conclusions

In this paper, we set out to investigate the role of government quality in determining locational preferences and hence the attractiveness of European NUTS-2 regions for future residents. Using a data set of 254 European NUTS-2 regions covering the time period 1995 to 2009, we first analysed the importance of the standard economic and demographic characteristics and confirmed that, as expected, they have played a decisive role in explaining perceived place-specific preferences in the different regions of Europe. This connects our results to previous analyses of regional attractiveness in Europe. A main advantage of using net migration as a signal of utility differences across sub-national regional space is they may be associated with people’s locational preferences. Using this approach, regional attractiveness or utility may not only be inferred based on income-related factors, but also on alternative site-specific factors such as local government quality, which represents the main focus of this paper. The regional Quality of Government data set of the University of Gothenburg has provided us with measures of local corruption, rule of law, government effectiveness, and government accountability, which are compatible with a raft of more traditional determinants of population mobility at a regional level. The findings of the analysis indicate that, on top of the traditional drivers of migration, quality of government plays an important role in decisions to relocate in Europe. Better local government is associated with higher net migration rates and may thus signal higher regional locational preferences, based on Tiebout’s individual revealed preferences approach. This result is robust to the introduction of alternative specifications of the model and to the use of alternative methods to assess the connection between government quality and regional attractiveness. The findings also concern not just the general impact of local government quality, but point more specifically to an important impact of local corruption levels, as well as of indicators referring to local politics and government efficiency. Low levels of graft and private rent-seeking in positions of public power combined with customer-driven and effective and efficient local government structures and local bureaucracies can be considered strong pull factors for future residents.

Our analysis integrates two of the major themes of the European Union’s Sixth Cohesion report (EU 2014)—quality of governance and labour mobility—and draws conclusions that, in line with the Cohesion report (EU 2014), underline the salience of local institutions and governance not only for socio-economic development (Charron et al. 2014), innovation (Rodríguez-Pose and Cataldo 2015), inequality (Kyriacou and Roca-Sagalés 2014), or the effectiveness of public policies, in general, and European development policies, in particular (Rodríguez-Pose and Garcilazo 2015), but also as a fundamental determinant of the appeal of European regions to migrants. As such, it presents evidence that should feed into the debate about how to design effective regional development policies which may contribute to enhance the attractiveness of places and help understand the implications of the considerable differences in institutional quality across regions in Europe. In a context in which ‘place-based’ approaches to territorial development profoundly influence the current debate on regional policies (EU 2014), the erection of effective institutions at the local and regional level may represent a crucial aspect in promoting the constructive role of the state in shaping regional development patterns. Better institutions at a local and regional level may therefore amount to a key component in creating and channelling incentives for workers and businesses, consequently influencing regional and urban outcomes, such as population change and economic development.

Notes

Some studies, however, still only find a limited or even no effect of amenities on regional population change, in particular in a European context (see for instance Cheshire and Magrini 2006; Faggian and McCann 2009).

In arguing that net migration reflects a more ‘objective’ measure of regional attractiveness, we follow Faggian et al. (2012:164), who claim that regional net migration reveals ‘the representative individual’s assessment of where his/her well-being will be improved, [and] is a strong candidate as an indicator of regional well-being’. As no single quality-of-life indicator captures all aspects of regional attractiveness, using net migration data allows for a more comprehensive assessment of the ‘voting with their feet’ approach. Resorting to net migration as an indicator of locational desirability, nevertheless, still represents an imperfect attractiveness measure, although its use somewhat mitigates the risks associated with more ‘subjective’ well-being self-assessments from survey data. We argue that longer-lasting net migration patterns reveal places that are generally preferred.

Our conceptual framework models net migration through households and firms’ adjustments to spatially different productivity levels and site-specific non-economic elements. The concept is based on a static general equilibrium following Roback (1982) and the dynamic general equilibrium approach following Rappaport (2004, 2007).

The calculation of the spatial weights follows Le Gallo and Ertur (2003), and computes centroid distances between the a region and its k-nearest neighbours, where the spatial weighting matrix is defined as:

$$\begin{aligned} W(k)=\left\{ \begin{array}{l} {w}_{{ij}}^{*} ={1}\quad {\mathrm {if}}\ {d}_{{ij}} \le d_{{i}} {(k)} \hbox { and } \quad w_{{ij}} {(k)}=\sum _{{j}} {{w}_{{ij}}^{*}{(k)}} \\ {w}_{{ij}}^{*} ={0}\quad {\mathrm {if}}\ {{d}}_{{ij}} \ge {d}_{{i}} {(k)} \hbox {, or } \quad i=j \end{array} \right. \end{aligned}$$with \(d_{{ij}}\) denoting the distance of order k between region i and j, and \(w_ij\) and \(w_{ij}^{*}\), denoting elements of a standardised and unstandardised weight matrix. For our computations, we use k equal to 10.

The survey—the largest conducted on government quality at a regional level in the EU—encompasses, on average, 200 participants per region, who responded to 34 quality of government, and demography-related questions. The questions covered education, health care, and law enforcement services frequently provided by local or regional authorities. For more detailed information on the survey, as well as on the construction of the indices, see Charron et al. (2014).

Natural amenity data for European NUTS-2 regions are only available for the EU-15. The 2SLS and IV–GMM estimations, including the time-invariant amenities, are presented in Sect. 5.3.

The migration rate is derived from a simple transformation of the difference in regional population stocks in period t and \(t-1\). Region i’s population stocks in period \(t-1\) are defined \(P_{it-1} = P_{{it}} +\hbox {Em}_{{it}} -\hbox {Im}_{{it}} +d_{{it}} -b_{{it}} \). Rearranging results in \({P}_{{it}-1} = P_{{it}} +\hbox {Em}_{{it}} -\hbox {Im}_{{it}} +{d}_{{it}} - {b}_{{it}} \), where \(\hbox {Im}_{{it}}\) and \(\hbox {Em}_{{it}}\) reflect immigration and emigration of region i at time t, and where \({d}_{{it}}\) and \(b_{{it}}\) denote a region’s number of deaths and births in period t.

Time and country dummies prove to be highly significant as revealed by the appropriate tests.

Additional regressions, including fixed and random effects, as well as a dynamic panel data (i.e. Arellano-Bond) estimator are presented in the ‘Appendix’.

Potential endogeneity concerns for all regressors are also partially addressed by using lagged values.

The interaction term between the young population and agricultural employment share variables, however, is not significant.

The findings in Table 3, Column 8 have to be considered with some caution, as introducing all regional quality of government variable simultaneously may lead to some inconsistency in the parameter estimates. This is due to the relatively high correlation between them and by the possibility that some of them may be jointly or simultaneously determined.

The validity of the internal instruments is confirmed by the corresponding Hansen J test statistics. The test results are available upon request.

References

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson J (2001) The colonial origins of comparative development: an empirical investigation. Am Econ Rev 91(5):1369–1401

Acemoglu D, Johnson S (2005) Unbundling institutions. J Polit Econ 113:949–995

Barro RJ (1999) Determinants of democracy. J Polit Econ 107(2):158–183

Beine M, Sekkat K (2013) Skilled migration and the transfer of institutional norms. IZA J Migr 2:9

Bertocchi G, Strozzi C (2008) International migration and the role of institutions. Public Choice 137:25–102

Bode E, Zwing S (1998) Interregionale Arbeitskräftewanderungen: Theoretische Erklärungsansätze und empirischer Befund, Kieler Arbeitspapiere, Nr. 877, Institut für Weltwirtschaft

Bond S, Hoeffler A, Temple J (2001) GMM estimates of growth. University of Bristol, Working Paper

Camagni R, Cappello R (2009) Territorial capital and regional competitiveness: theory and evidence. Stud Reg Sci 39(1):19–39

Caselli C, Coleman J (2001) The U.S. structural transformation and regional convergence: a reinterpretation. J Polit Econ 109(3):584–616

Charron N, Lapuente V, Dijkstra L (2014) Regional governance matters: a study on regional variation in quality of government within the EU. Reg Stud 48(1):68–90

Cheshire PC, Magrini S (2006) Population growth in European cities: weather matters-but only nationally. Reg Stud 40(1):23–37

Davis B, Stecklov G, Winters P (2002) Domestic and international migration from rural Mexico: disaggregating the effects of network structure and composition. Popul Stud J Demogr 56(3):291–309

Day MK (1992) Interprovincial migration and local public goods. Can J Econ 25(1):123–144

Deas I, Giordano B (2001) Conceptualising and measuring urban competitiveness in major English cities: an exploratory approach. Environ Plan A 33:1411–1429

De Voretz DJ (2006) Immigration policy: methods of economic assessment. Int Migr Rev 40(2):390–418

Docquier F, Lodigian E, Lodigiani E, Rapoport H, Schiff M (2010) Brain drain and home country institutions. Université Catholique de Louvain, Mimeo

Engerman SL, Sokoloff KL (2000) History lessons: institutions, factors endowments, and paths of development in the new world. J Econ Perspect 14(3):217–232

EU (2014) Investment for jobs and growth. Promoting development and good governance in EU regions and cities. Sixth report on economic, social and territorial cohesion. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

Faggian A, McCann P (2009) Human capital, graduate migration and innovation in British regions. Camb J Econ 33:317–333

Faggian A, McCann P, Sheppard S (2007) Some evidence that women are more mobile than men: gender differences in UK graduate migration behaviour. J Reg Sci 47:517–539

Faggian A, Olfert MR, Partridge MD (2012) Inferring regional well-being from individual revealed preferences: the ‘voting with your feet’ approach. Camb J Reg Econ Soc 5:163–180

Ferguson M, Ali K, Olfert MR, Partridge M (2007) Voting with their feet: jobs versus amenities. Growth Change 38:77–110

Ghatak S, Levine P (1993) Migration theory and evidence: an assessment. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 769, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London

Greasley S, John P, Wolman H (2011) Does government performance matter? The effects of local government on urban outcomes in England. Urban Stud 48(9):1835–1851

Harris JR, Todaro MP (1970) Migration, unemployment and development: a two sector analysis. Am Econ Rev 60:126–142

Hicks J (1932) The theory of wages. McMillan, London

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Mastruzzi M (2009) Governance Matters VIII: aggregate and individual governance indicators, 1996–2008. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4978

Kishlansky M, Geary P, O’Brien P (2003) Civilization in the West, 5th edn. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Kyriacou AP, Roca-Sagalés O (2014) Regional disparities and government quality: redistributive conflict crowds out good government. Spat Econ Anal 9(2):183–201

La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1999) The quality of government. J Law Econ Organ 15:222–279

Le Gallo J, Ertur C (2003) Exploratory spatial data analysis of the distribution of regional per capita GDP in Europe, 1980–1995. Pap Reg Sci 82:183–201

Malecki E (2004) Jockeying for position: what it means and why it matters to regional development policy when places compete. Reg Stud 38(9):1101–1120

Massey DS, Arango J, Hugo G, Kouaouci A, Pellegrino A, Taylor JE (1993) Theories of international migration: a review and appraisal. Popul Dev Rev 19(3):431–466

Massey DS, Arango J, Hugo G, Kouaouci A, Pellegrino A, Taylor JE (1998) Worlds in motion. Understanding international migration at the end of the millenium. Oxford University Press, Oxford

McGranahan DA (2008) Landscape influence on recent rural migration in the US. Landsc Urban Plan 85:228–240

McKenzie D, Rapoport H (2007) Network effects and the dynamics of migration and inequality: theory and evidence from Mexico. J Dev Econ 84(1):1–24

Mitchell TD, Carter TR, Jones PD, Hulme M, New M (2004) A comprehensive set of high-resolution grids of monthly climate for Europe and the globe: the observed record (1901–2000) and 16 scenarios (2001–2100), Tyndall Centre Working Paper no. 55, Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, New York

Partridge M, Rickman D (2003) The waxing and waning of US regional economies: the chicken-egg of jobs versus people. J Urban Econ 53:76–97

Partridge M, Rickman D (2006) Fluctuations in aggregate US migration flows and regional labor market flexibility. South Econ J 72:958–980

Partridge MD (2010) The dueling models: NEG vs amenity migration in explaining U.S. engines of growth. Pap Reg Sci 89:513–536

Pritchett L (2006) Let their people come: breaking the deadlock in international labor mobility. Brookings Institution Press, Washington

Puhani PA (2001) Labour mobility: an adjustment mechanism in Euroland? Empirical evidence for Western Germany, France and Italy. Ger Econ Rev 2:127–140

Rappaport J (2004) Why are population flows so persistent? J Urban Econ 56:554–580

Rappaport J (2007) Moving to nice weather. Reg Sci Urban Econ 37:375–398

Roback J (1982) Wages, rents, and the quality of life. J Pol Econ 90:1257–1278

Rodríguez-Pose A, Di Cataldo M (2015) Quality of government and innovative performance in the regions of Europe. J Econ Geogr 15(4):673–706

Rodríguez-Pose A, Garcilazo E (2015) Quality of government and regional cohesion: examining the economic impact of structural funds in European regions. Reg Stud 49(8):1274–1290

Rodríguez-Pose A, Ketterer TD (2012) Do local amenities affect the appeal of regions in Europe for migrants? J Reg Sci 52(4):535–561

Rodríguez-Pose A, von Berlepsch V (2014) When migrants rule: the legacy of mass migration on economic development in the United States. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 104(3):628–651

Rodríguez-Pose A, von Berlepsch V (2015) European migration, national origin and long-term economic development in voting with the United States. Econ Geogr 91(4):393–424

Rotte R, Vogler M (2000) The effects of development on migration: theoretical issues and new empirical evidence. J Popul Econ 13:485–508

Spilimbergo A (2009) Democracy and foreign education. Am Econ Rev 99(1):528–543

Tiebout C (1956) A pure theory of local expenditures. J Polit Econ 64(5):416–424

Zimmermann KF (2005) European labour mobility: challenges and potentials. De Economist 153(4):425–450

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Martin Andersson, the editor in charge, and to three anonymous referees for their insightful comments to earlier versions of the manuscript. The paper has benefited from the generous financial support of the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC Grant Agreement Number 269868. The paper reflects only the views of the authors and should not be attributed to the European Commission.