Abstract

In a national ballot in 2009, Swiss citizens surprisingly approved an amendment to the Swiss constitution to ban the further construction of minarets. The ballot outcome manifested reservations and anti-immigrant attitudes in regions of Switzerland which had previously been hidden. We exploit this fact as a natural experiment to identify the causal effect of negative attitudes towards immigrants on foreigners’ location choices and thus indirectly on their utility. Based on a regression discontinuity design with unknown discontinuity points and administrative data on the population of foreigners, we find that the probability of their moving to a municipality which unexpectedly expressed stronger reservations decreases initially by about 40%. The effect is accompanied by a drop of housing prices in these municipalities and levels off over a period of about 5 months. Moreover, foreigners in high-skill occupations react relatively more strongly highlighting a tension when countries try to attract well-educated professionals from abroad.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The question of whether people care about how they are perceived by others is important for understanding individual decision-making since many choices involve aspects of social interaction. People’s attitudes towards one another are obviously central for bonding decisions, but they are also crucial in determining the choices individuals make when selecting an organization for employment or leisure. The issue might also arise when people decide about which community they wish to live in. In this paper, we focus on this relationship and ask to what extent the resident population’s attitudes are relevant for such decisions. In particular, we analyze how foreigners react to unexpectedly revealed reservations towards their group studying their location choices.

Attitudes towards foreigners influence the interaction between immigrants and the native population in many ways. This matters for the successful realization of gains from trade between these two parties as well as for the immigrants’ integration (see, e.g., Algan et al. 2012; Akay et al. 2017). Specifically, a host country’s culture of welcome might affect where mobile foreigners are willing to locate, and is crucial for regions that need to attract experts from abroad. There is a large body of literature which discusses the sources and expression of negative attitudes towards foreigners as reflected, for example, in right-wing extremism (e.g., Hainmueller and Hopkins 2014). However, foreigners’ behavioral reactions to these attitudes and the consequences that they have for their welfare are less often addressed.Footnote 1 While economic models and analyses of foreigners’ location choices offer an approach to learn about foreigners’ valuations of the overall attractiveness of an environment, this field of research typically neglects the political attitudes of the resident population. Moreover, the attempt to analyze the relationship between the presence of foreigners and residents’ attitudes towards them poses a severe methodological challenge, as it is necessary to overcome an inherent simultaneity (Dustmann and Preston 2001). On the one hand, the presence of foreigners may affect natives’ preferences and attitudes. Getting to know foreigners may reduce prejudices, as postulated by the so-called contact hypothesis, or the presence of foreigners may aggravate negative attitudes, as natives fear pressure on the labor market and welfare system, and expect increases in the crime rate or the alienation of their own culture. On the other hand, the attitudes of natives towards foreigners may affect the presence of immigrants. Foreigners might move less to areas where residents have reservations about them, where they fear discrimination or even physical abuse.

In this paper, we analyze the role of attitudes towards foreigners in their choice of residence based on a unique setting which allows us to address the identification problem of simultaneity. As a moderator, we integrate identity utility, as introduced by Akerlof and Kranton (2000). It allows us to capture the idea that perceived negative attitudes towards foreigners affect their utility. In a national ballot 2009, Swiss citizens voted on whether the further construction of minarets should be prohibited (the so-called minaret initiative). Against the recommendation of the Swiss Federal Assembly and the predictions of leading opinion pollsters, the amendment to the Swiss constitution was accepted with a clear majority. The ballot outcome manifested reservations and anti-immigrant attitudes in regions of Switzerland which had previously been hidden. There were municipalities where voters unexpectedly deviated strongly from their past voting behavior on migration-related issues. We exploit this fact and study whether the inflow of foreigners to these particular municipalities declined in the aftermath of the vote, which would be consistent with lower expected utility and provide evidence that individuals react to perceived attitudes towards their social group.

The empirical analyses draw on administrative data for the universe of foreigners living in Switzerland which allow us to study their moving behavior before and after the national vote on the minaret initiative. We proceed in two steps. First, in a preliminary simple analysis, we estimate the change in the probability that some foreigner moves to a municipality that unexpectedly approved the minaret initiative in the months after the vote. The results suggest a reduction in this probability about 3 months after the vote has taken place. Second, in the main analysis, a more appropriate econometric approach is pursued flexibly taking canton-specific situations into account. Based on a simulation study, we expect that any effect materializes as a sharp decline in the likelihood that a foreigner chooses to move to a municipality that had unexpectedly revealed its reservations towards foreigners some time after the vote. Since the point in time at which the effect can be observed is not deterministically predictable, the change in residential relocation patterns is analyzed based on a regression discontinuity design (RDD) with unknown discontinuity points (Porter and Yu 2015). We find such discontinuous jumps in the moving pattern of foreigners in 12 cantons. We observe that foreigners are deterred from locating in municipalities that unexpectedly revealed negative attitudes towards them (“switcher municipalities,” for a definition, see Section 2.2). The estimated effect is sizable. In cantons where reactions could be identified, the probability that a foreigner chooses one of these municipalities drops, on average, by approximately 4.9 percentage points within the first month relative to a pre-intervention level of 13%, and thus by about 40%. Our interpretation that switcher municipalities became less attractive due to the change in perceived political attitudes is consistent with reactions in the moving behavior to other types of municipalities. We observe that foreigners are more likely to move to municipalities that became relatively more open and are equally likely to move to municipalities whose relative position has not changed.

Several validation checks suggest that the assumptions underlying the RDD hold: Neither the number of foreigners moving nor the municipalities that unexpectedly reveal their reservations about immigrants are systematically different before and after the threshold dates. The effect holds to a similar extent for groups of foreigners other than Muslims. This suggests that foreigners identify with the affected minorities and that they perceived the support for the initiative as being an expression of negative attitudes towards immigrants in general. Moreover, we document that the overall effect is similar in size for individuals moving within a narrow radius, which is most probably not attributable to a job change. Still, the effect differs across specific groups of foreigners and over time. While it is substantial for first-generation foreigners, there is no discernible effect for second-generation foreigners. The latter are often well assimilated and seem to be less affected by the revealed attitudes. This finding emerges from exploring a potential alternative explanation, i.e., that landlords will dare to discriminate more against foreigners once they learn about the reservations of their fellow citizens. This supply-driven reaction, however, would to some extent affect foreigners in general. We further find that foreigners in high-skill occupations react more strongly than foreigners in low-skill occupations. While this finding is interesting in itself, it further suggests a primarily demand driven mechanism. Finally, the effect fades after about 5 months. This might be due to the declining salience of the issue as time elapses and/or due to adjustments in the housing market. In the latter case, lower rents compensate foreigners for the disutility of living in an environment with negative attitudes towards them. The results of a supplementary analysis indeed suggest a reduction in housing prices for switcher municipalities in the aftermath of the vote. Our data does not allow investigating potential reactions by the native population. Otherwise, we could explore whether the identified reaction on the housing market is due to changes in citizens’ location choices in response to the newly revealed attitudes. It is well conceivable that some Swiss also shun municipalities where they consider their fellow citizens to hold political preferences they could not align with. This suggests that voting outcomes could be considered an important source of information contributing to preference-based spatial sorting more broadly.

Our analysis contributes inter alia to the growing literature on the interdependent relationship between the presence of immigrants and attitudes towards them. Studies that investigate the effect that an inflow of foreigners has on the native population’s attitudes hereby face a methodological challenge. There is the possibility of common unobserved drivers as well as potential reverse causality, which arises due to a possible effect from attitudes on foreigners location choices. In pioneering work, Dustmann and Preston (2001) analyze the effect of the local ethnic composition on natives’ attitudes towards foreigners in the UK. They propose an IV approach by using the ethnic composition of large-scale areas as an instrument for the composition in local areas. In their study, simultaneity bias matters and correcting for it reveals that a higher share in the (ethnic) minority population is associated with more hostile attitudes in the majority population. Several studies build on this idea to take potential endogeneity into account in other contexts (see, e.g., Dill 2013; Kuhn and Brunner 2018; Barone et al. 2016; Méndez Martínez and Cutillas 2014; Halla et al. 2017; Gerdes and Wadensjö2008). While the potential relationship between attitudes and location choices is acknowledged, there is little direct evidence on whether foreign individuals’ location choices indeed relate to perceived attitudes per se or whether the potential relationship is rather driven by resulting tangible (living) conditions.

To the best of our knowledge, there are five studies that are concerned with the question of whether minority groups’ location choices react to attitudes or behavior towards them. An early analysis by Tolnay and Beck (1992) documents the relationship between racial violence in US counties and the outmigration of the threatened group between 1910 and 1930. In related work, Henry (2009) finds that African Americans are less likely to move to places where they face a higher risk of becoming the victim of a hate crime. These interesting findings are primarily descriptive in nature and likely linked to tangible living conditions, i.e., the fear of physical violence. Waisman and Larsen (2016) investigate the quasi-random variation in the initial placement of asylum seekers in Sweden in conjunction with measures of attitudes based on survey data, which they use to approximate migrants’ living conditions and potential discrimination. They find some evidence that refugees’ subsequent location choices are related to natives’ surveyed attitudes. Damm (2009) investigates regional factors that influence immigrants’ location choices in Denmark. She also uses a quasi-random placement of asylum seekers and finds that the hazard to leave the municipality which he or she is assigned to increases with the share of votes for right-wing parties. The behavioral reaction is interpreted as welfare-seeking behavior. The most recent study is by Gorinas and Pytliková (2017), who investigate whether surveyed attitudes towards immigrants have an impact on migration flows at an international level. They perform a cross-national study and find that the surveyed dismissive attitudes of natives are negatively correlated with migrant inflows.

While these five studies indicate that adverse conditions are related to minorities’ location choices, perceived attitudes cannot be separated from, and likely capture, related tangible (living) conditions, they might possibly work indirectly, and/or their potential endogeneity is not accounted for. We pursue a novel strategy and measure attitudes towards immigrants directly based on voting behavior in ballots widely observed by the public. We thereby exploit a surprising revelation of negative attitudes to identify the causal effect of attitudes on location choices. This approach allows us to compare location choices within the same choice set of municipalities and the same population before and after the new information is available and thus enables us to capture the effect of perceived attitudes independently of tangible living conditions. Furthermore, our analysis is not confined to a specific group of foreigners, such as refugees, but applies to the large group of labor migrants. Finally, our empirical study presents the first comprehensive application of a regression discontinuity design with unknown thresholds as recently proposed by Porter and Yu (2015).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides background information on the institutional setting as well as on the informational conditions defining the municipalities that unexpectedly reveal a shift towards an anti-immigration position. Section 3 describes our reasoning on how perceived attitudes influence an individual’s utility and how this affects his or her location choice. Based on these considerations, Section 4 outlines the empirical strategy. Our data sources are described in Section 5. The results are presented in Section 6, and validated and discussed in Section 7. Section 8 offers complementary evidence on the development of housing prices. Section 9 concludes.

2 Background and informational setting

Our study draws on information about voting behavior in national referendums that is used to infer residents’ revealed attitudes towards foreigners and the changes in these publicly visible attitudes over time. In order to understand this specific informational setting, we first provide some background information about one specific proposition, the minaret initiative, and briefly introduce direct democratic decision-making in Switzerland. In a second step, we specify the circumstances which characterize voting behavior in the minaret initiative and explain why the vote outcome unexpectedly reveals reservations towards foreigners. Finally, we discuss how the ballot outcome entered foreigners’ information base.

2.1 The vote on the minaret initiative

On November 29, 2009, a majority of Swiss voters unexpectedly approved an initiative that banned the further construction of minarets in Switzerland.Footnote 2

In the aftermath of 9/11 with its increased fear of terrorism, a discussion arose about whether practicing Muslims in Switzerland would threaten the democratic order. In this anxious atmosphere, two Swiss center-right conservative parties, i.e. the Swiss People’s Party and the Federal Democratic Union, started preparations for the minaret initiative against the further construction of minarets. At this point in time, there were only four minarets in the whole of Switzerland. For their construction a permit was necessary, requiring that the construction plans comply with the cantonal and communal rules. Due to these existing restrictions, it was not to be expected that many minarets would be built in Switzerland. It was also clear that the proposed amendment would not change anything in the religious practice of Swiss Muslims. Mosques were already present, and their right to exist was not affected by the initiative.

During the campaign and beyond, the initiative was widely discussed in the Swiss media and attracted global attention. The degree of public attention that this issue attracted can partly be ascribed to the campaign advertisement. One of the initiative’s campaign posters showed a woman in a black niqab and the Swiss flag with looming minarets representing rockets. The Federal Commission against Racism judged that this visual tactic would jeopardize public peace and therefore banned it from being displayed in some towns and cantons.Footnote 3 Overall, the campaign raised fundamental discussions about religious freedom, cultural diversity, and tolerance in Switzerland and was very salient in the media. The discussion was not limited to Muslims in Switzerland, but also involved the issue of migration and the treatment of minorities in general (see, e.g., Ettinger and Imhof 2014).

Most parties and the Swiss Federal Assembly recommended that the initiative be rejected. However, contrary to general expectations as well as the forecasts of leading opinion researchers that the initiative would not be passed, it was accepted with a clear majority of 57.5% of the votes. Many citizens were mobilized (53.3%) and expressed more than a signal against the spread of the Islam in Switzerland but a general discomfort in the face of societal change and immigration experienced as a threat to Swiss cultural identity (see, e.g., Freitag and Rapp 2013 or Wehrli 2009). From the perspective of many foreigners, the vote outcome was perceived as a disturbing sign that provoked a general sense of exclusion (see, e.g., the individual reactions reported in Thiriet 2009). The decision came into effect at the national level and no minarets have been built since. In the exercise of their religion, however, nothing has changed for Muslims in Switzerland.

In the aftermath of the unexpected approval, there was substantial post-election news coverage. On all the Swiss media channels, the unreckoned outcome was discussed and the municipal voting patterns made prominent news. Most Swiss newspapers presented maps indicating which municipalities of a canton supported or rejected the initiative. Sometimes, even the vote district results were discussed and displayed.Footnote 4 For Swiss citizens and foreigners alike, it was easy to learn about attitudes across municipalities and to spread the word about the municipalities that were expressing more pronounced reservations towards foreigners.

2.2 Attitudes towards foreigners across municipalities

The acceptance of the initiative did not only come as a surprise, but the voting pattern across municipalities did not match the rather stable political spectrum of views on migration manifested in prior votes. There were municipalities that unexpectedly revealed anti-immigrant attitudes, which external observers had not previously perceived. We thus see the event as an exogenous shock in perceived attitudes towards foreigners in some municipalities.

The vote on the minaret initiative provides a particularly attractive setting to capture information about citizens’ attitudes. It can be conceptualized as a low-cost decision involving virtually no instrumental considerations about economic consequences, but rather allowing fully expressive voting behavior. Previous votes, such as the initiative “for the regulation of immigration” held on September 24, 2000, provoked serious concerns about negative economic repercussions in the case of their approval. The voting behavior on the minaret initiative thus revealed rather unambiguous signals about attitudes towards foreigners and allows us to measure potential changes in the publicly visible positioning of municipalities, i.e., changes relative to the best approximation as derived from previous voting behavior. Importantly, access to representative information about regional attitudes is just as accessible to us as researchers as it is to the people observed in our study. We consider the changes in perceived attitudes as exogenous shock to individuals’ information base. The outcome is not anticipated and reveals new information. Information, which foreigners can incorporate in their perception about the political orientation of people across municipalities.

In order to use the exogenous shock to measure the effect of perceived attitudes on foreigners’ location choices, we identify the municipalities that revealed previously unknown preferences based on a comparison with relevant votes in the past. In particular, we rely on four votes that occurred within a time frame close to the minaret initiative and which are sufficiently contextually related to it, i.e., in that they also involve the expression of attitudes towards foreigners. We code the voting results such that a higher vote share reflects more restrictive attitudes towards migration and foreigners.Footnote 5

Specifically, a municipality is characterized as having unexpectedly revealed negative attitudes towards foreigners if the following criteria are fulfilled:

-

The average support for restrictive migration policies in the past is below the mean for the canton they belong to.

-

The swing to a more restrictive position, as expressed in the vote on the minaret initiative, is larger than the mean change across all the municipalities within the canton.

-

The support for the minaret initiative exceeds 50% of the municipality’s active electorate.

We label these municipalities with the generic term “switcher municipalities.”

The first criterion is motivated by the idea that the respective municipalities were perceived as being relatively tolerant up to the vote on the minaret initiative. The second criterion ensures that only municipalities which experienced a large shift are considered to be switchers, given that nearly all the municipalities shifted to the right. The third criterion guarantees that the municipality voted in favor of the minaret initiative, thus providing a signal that the majority agrees with the proposition. The latter point is important for the media coverage (see below). Based on these three criteria, we classify approximately 24% of all municipalities in Switzerland as switchers. The graphs in Fig. 1 show how the voting results are distributed when comparing switcher and non-switcher municipalities.

First, citizens in switcher municipalities voted less restrictive on migration issues in former votes (used to calculate the ex ante perceived level of critical attitudes towards foreigners). Second, however, in the minaret initiative, municipalities from the two groups cast similarly restrictive votes, on average. Third, when focusing on the change in the support of a restrictive position towards migration, a larger difference is observed for switcher municipalities than for non-switcher municipalities. Descriptive statistics on the criteria are reported in Table 8 in Appendix 2.

As a generally large fraction of the voting population approved a restrictive position in the minaret initiative, it could well be that the relative positioning of the municipalities in terms of expressed reservations has not changed at all. Accordingly, we rank municipalities within their cantons, once with regard to their average yes vote share in the four migration-related propositions that took place before the minaret initiative, and once on the basis of the vote outcomes in the minaret initiative. Figure 2 shows the average relative rank changes for switcher and non-switcher municipalities in all Swiss cantons. A positive change indicates that the municipality increased its rank by expressing a relatively more restrictive position towards immigration. Overall, a clear picture emerges that switcher municipalities gained in rank and non-switcher municipalities lost in rank. The relative strength of expressed reservations towards foreigners has thus changed between switcher and non-switcher municipalities. Two exceptions being, firstly the canton of Geneva, where there are no switching municipalities as no municipality accepted the initiative and the canton of Zug where the average rank changes are zero and no switcher municipality changed its relative position.

Rank change of switcher and non-switcher municipalities. A positive rank change indicates that the involved municipalities voted more restrictively on migration in the minaret initiative than in previous votes (compared to the other municipalities in a cantonal ranking). The rank change is measured as a percentage of the number of municipalities within the canton

3 Theory

In this section, we derive our main hypothesis of how newly revealed perceived attitudes could affect individuals’ location choices and under which conditions such reactions can be ascribed to perceived attitudes per se. We continue by our reasoning of how such reactions could materialize and be identified in observational data of individuals moving behavior.

3.1 Location choice including identity utility

We assume that the economy is in equilibrium and that individuals take municipality characteristics as given when choosing their location. We explicitly focus on the location choice and take the decision to move as given. Thus, we think about the choices of individuals once they have decided that they will move and face a continuum of municipalities and their characteristics in their choice set. We argue that their decision to move is much less affected by the new information about attitudes towards foreigners than their decision about where to move. First, the decision to move is much more costly than a change in the decision about where to move. Second, individuals residing in municipalities which were disclosed to hold negative attitudes towards foreigners might have already been aware of their neighbors’ attitudes and would know that living conditions have not changed. As we argue that the surprising vote outcome is primarily a revelation of attitudes, rather than a change in attitudes.Footnote 6

The utility Uijt of an individual i (i = 1,...,N) living in municipality j (j = 1,..,J) at time t depends on several municipality characteristics Cjt and individual characteristics Idit. Municipality characteristics that influence individual utility are, e.g., taxes, housing prices, the provision of public goods, but also natural beauty or social ties. Individual characteristics involve an individual’s income, the preference for housing, and other individual characteristics such as family status.

If people have a sense of self and care about how they perceive themselves as human beings and how they are perceived by others, this sense (or identity utility) should be an additional factor entering the expected utility of living in a particular municipality (see, e.g., the model on identity by Akerlof and Kranton 2000). This proposition would be in line with research in social psychology. There, it is well documented, that perceiving even slightly repellent behavior of others can produce psychological and physical distress. Investigations on ostracism show that individuals strongly react to perceived exclusion, as it threatens the fundamental needs of belonging and increases negative affect.Footnote 7 In a recent survey study, Rudert et al. (2017), for example, investigate whether foreigners feel ostracized after a popular vote on migration in Switzerland in 2014. They find that foreigners’ perceptions of their environment reflect the vote outcome and that immigrants’ need for belonging is less satisfied where citizens voted more restrictively. This holds even though the investigated group would not have been materially affected by the resulting legislation.

The behavior or perceived attitudes of others which, in our case, refer to the revealed attitudes of natives can differ across municipalities j and in time t. We assume that individuals update their information about the set of choices at the level of municipalities when they move. This includes their perceptions of attitudes towards their social class based on the past voting record of the municipalities.

3.2 Changes in perceived attitudes and moving decisions

Revealed attitudes towards foreigners in a municipality may change over time and thus also individuals’ optimal location choices. Individuals choose their location such that their utility is maximized within their choice set. Thus, individual i will choose to locate in municipality j if, and only if,

the utility to live there is higher than in all other municipalities in the choice set (see, e.g., McFadden 1974).

The location choice of individuals is in equilibrium before t and new information about attitudes across municipalities is revealed between t and t + 1, leading individuals to update their utility expectations. In our specific setting, the newly revealed information is the voting outcome on the minaret initiative in Switzerland. This new information can be seen as an exogenous change in perceived attitudes, as it was unexpected and does not have direct implications for the other municipality characteristics. Assuming that the utility is decreasing in reservations or negative attitudes, this revelation should lead to a lower probability to choose a municipality revealing more negative attitudes than has been expected. However, it has to be considered that this is only true if the relative positioning of municipalities with respect to this characteristic also changes. If all municipalities in an individuals’ choice set were to express stronger reservations and the relative positioning stayed the same, we would not expect any change in observed behavior. Our definition of switcher municipalities above does take this reasoning into account. We would thus expect that individuals shun to move to municipalities which expressed stronger reservations than expected, and changed their positioning relative to the other municipalities in the choice set, after the vote has taken place.

Whether somebody is affected by a change in attitudes towards foreigners depends on the extent to which he or she identifies with this social group or cares about political attitudes in this dimension. Residents with a foreign passport might identify strongest with the social group of foreigners due to their ancestry, ethnicity or prior experiences. As an individual to some extent chooses his or her identity, it is also possible that an individual’s self-ascribed social category reacts to the new information. This idea is grounded in the rejection-identification model in social psychology (Tajfel 1978; Branscombe et al. 1999). This theory asserts that when a minority group member perceives prejudice against his or her group, that member will develop a stronger identification with the group in order to reduce the psychological cost of perceived prejudice. Moreover, group identities may develop as a result of perceived prejudice, i.e., minority groups tend to identify with other minority groups under threat (Schmitt et al. 2003; Wesselmann et al. 2009).

Building on these considerations from economics and social psychology, we hypothesize that a negative change in perceived attitudes leads to a lower expected utility of residing in these municipalities, and thus to a lower probability that foreign individuals move to municipalities surprisingly revealing negative attitudes. In our context, the minaret initiative, we would expect not only Muslims but also other groups of foreign residents to experience ostracism, as their identity as foreigners in Switzerland becomes salient. Specifically, we would also expect EU citizens to be negatively affected by the initiative, if the identity as a foreigner is the moderating factor. This hypothesis would in principle also hold for Swiss citizens who care about political attitudes of fellow residents in this dimension.

If an individual who would have chosen j in t chooses a different municipality k in t + 1, in t the expected utility to live in j is higher than that in k, and the reverse in t + 1. This might be the case either because the utility to live in j has fallen from t to t + 1, or the utility to live in k has risen, or both.

There are two crucial conditions that need to hold in order to ascribe a potential change in the location choice to the change in perceived local attitudes towards the social group.

-

Municipality characteristics have not changed systematically between t and t + 1 (Cjt = Cjt+ 1 = Cj).

-

Moving individuals are, on average, the same in t and t + 1. Thus, individual-specific characteristics have not changed systematically between t and t + 1 (Idit = Idit+ 1 = Idi).

Given these conditions hold, the component in the utility function that could have changed the relative attractiveness of municipality j are perceived attitudes towards individuals’ social categories, potentially through identity utility.Footnote 8

3.3 Identification of reactions to perceived attitudes based on location decisions

Given the conditions mentioned before hold, it should be possible to identify the effect of the signal on the location choice by comparing the location decisions of foreigners who choose their residency before and after the vote has taken place. Thus, before, the information was revealed. Individuals decide to move at some point in time. Whether they find a new home on a specific day, say the day before or after the vote has taken place, can be considered as random with respect to a specific voting date. While an individual who finds a new apartment the day before the vote cannot incorporate the information on the outcome that will be revealed the next day in his or her choice, an individual who finds an apartment the day after can utilize the information on the outcome. Accordingly, individuals who decide to move and choose an apartment narrowly before the voting day can be used as a control group for those who make this decision shortly after the vote has taken place (Thistlethwaite and Campbell 1960). If revealed preferences of the voting population about their attitudes towards foreigners play no role for the relative attractiveness of municipalities, foreigners’ location decisions should, on average, be the same before and after the vote. However, if the mover is affected by perceived attitudes towards his or her group, we should observe a clear change in a mover’s location decision.Footnote 9

In order to apply this theoretical identification strategy, we would like to compare the location choices of people who decided where to move before the new information became public with those who decided afterwards. In particular, we would like to exploit the presence of switcher municipalities (described in Section 2), for which we argue that new information was unexpectedly revealed and which changed their relative positioning with respect to the openness towards foreigners. We thus aim to compare the probability that a foreigner chooses to move to one of the identified switcher municipalities before receiving the new information and after receiving it. If there was no lag between the time of the decision to move and the observed moving date, any effect should materialize right away, and the test could be approached using a regression discontinuity design, i.e., exploiting the local randomization in the time of the moving decision around the vote date. However, in observational data where only the moving and not the decision date is observed and where there is a lag, it is not evident which date separates the two groups. Shortly after the vote on the minaret initiative, many observed movers must have made their location choice before the vote took place and who were therefore unable to incorporate the new information. The longer the time is that elapses after the polling day, the larger will be the number of movers who have made their location choice based on the updated information set. The two groups might therefore overlap for some time until only movers who could incorporate the new information are observed. The corresponding time lag relative to the polling day might vary by region, as it might be affected by the length of notice periods and the situation in the housing market. In the next subsection, we provide a framework to analyze how the new information is incorporated into individuals’ observed location choices. In Section 4, we translate the insights into our main empirical strategy.

3.4 Incorporation of new information in observed location choices

The location choice equilibrium for foreigners materializes in a stable aggregate probability of choosing a particular municipality type. This holds over time and refers in our context to the switcher and non-switcher municipalities. For the individual location decision, we as statisticians, however, typically only observe the moving date, but not the decision date. Accordingly, “observed” individual location choices might be based on different information sets. There is a time span after the vote, during which we observe a mixture of those people who made their location choice before the information became public and those who decided subsequently. Any effect of the change in perceived attitudes materializes to the extent that the search generation that could incorporate the new information outweighs the prior search generations. This transition between the search cohorts could be smooth or sharp.

To gain an idea of how the effect could materialize, we perform a simulation analysis of individual location choices.Footnote 10 We simulate a simple location search with overlapping search generations. Two institutional scenarios are considered, and a negative treatment effect on the probability of moving to a switcher municipality is assumed. First, only search frictions exist, and people move once they have found an apartment. Second, a notice period is taken into account. It is revealed that in the second setting, the new information is incorporated later on in the aggregate outcome, i.e., in the inflow of individuals to the switcher municipalities, than in the first setting. Moreover, the adjustment pattern also reveals a much steeper drop in the probability of moving to a switcher municipality in the scenario with a notice period than in the scenario without one. With search frictions alone, in most cases, a rather gradual adjustment to the new equilibrium occurs.

Based on the assumption that it is random when an individual chooses to move and finds an apartment and that we know at which date the one group outweighs the other, a regression discontinuity framework seems suitable to analyze the incorporation of the new information. However, the threshold value to separate treated from control individuals is not as evident in the situation where the housing market and institutions affect the lag between the decision to move and the observed move. We apply the method of a regression discontinuity design with unknown discontinuity points (as introduced in the following Section 4) to identify the threshold and to measure the drop. The simulation clearly indicates that in an environment with legal restrictions that delay moving—such as a notice period—the method can separate the groups and find the simulated discontinuity. The discontinuity materializes at the point in time when the search cohort that could incorporate the new information starts to outweigh the cohort that could not incorporate the new information. This is not always the case in the scenario with search frictions alone. Given the rental agreements in Switzerland that stipulate mandatory as well as discretionary notice periods, the effect of a change in attitudes towards foreigners should be identifiable in observed moving dates.

4 Empirical strategy: RDD with unknown discontinuity points

Based on the theoretical considerations, we derived predictions on how individual location choices in response to new information translate into changes in aggregate migration flows between municipalities. In an environment with institutional restrictions, any displacement effect, is expected to materialize as a jump (or discontinuity) in the probability that a foreigner will choose to locate in a switcher municipality some time after the vote has taken place. In principle, this estimation problem shares many features of a classical regression discontinuity design (RDD). However, in most RDD applications, the discontinuity point is known, since it is, for instance, determined by the institution being analyzed. In our application though, this is not the case. The discontinuity point is the result of the interaction between the state of the housing market and institutional conditions such as the notice period. As a consequence, it is not deterministically predictable a priori when the discontinuity is expected to occur.

Porter and Yu (2015) have recently proposed an approach that is particularly well suited for the problem at hand. They develop a nonparametric procedure to perform regression discontinuity analyses when discontinuity points are unknown, but predicted by theory.Footnote 11 The procedure starts with a specification test. It tests the null hypothesis of no treatment effect, or that of no discontinuity in the relationship between a dependent variable y and a running variable x. Subsequently, the discontinuity point or threshold is estimated, given that the specification test rejects the null hypothesis. Finally, a standard RDD analysis is performed. As the authors find that the estimation of the threshold value does not affect the efficiency of the estimator of the discontinuity, the threshold value can be treated as known when estimating the RDD. The proposed approach, in principle, allows us to separate the treated and the untreated individuals in settings where a RDD would be appropriate; however, the threshold is unknown.

In classical RDD studies, the forcing variable, also referred to as the running variable, is used to determine the treatment status. When the value of this variable exceeds a certain threshold, observations are treated, but not so below this value. If individuals have no perfect control over the value of the forcing variable, the random variation narrowly around the threshold can be exploited to estimate the local average treatment effect (LATE) at this particular point (see, e.g., Hahn et al. (2001), Imbens and Lemieux (2008), and Lee and Lemieux (2010) for reviews of the RDD). The crucial assumptions for the validity of a sharp RDD are the local randomization and the continuity of conditional expectations, which provides that, without the treatment, both groups are alike at the threshold. The latter assumption makes sure that in a world without the treatment or in a world where everyone is treated, there would be no discontinuity in the conditional expectations at the threshold, i.e., that any effect can be attributed to the treatment.

In order to determine the point at which we can potentially separate the treatment and control group in our setting, we follow the approach proposed by Porter and Yu (2015) and apply the RDD with unknown discontinuity points. While this section concentrates on conveying the basic idea behind the procedure in a sharp RDD, we refer the interested reader to Appendix C in Slotwinski and Stutzer (2018) for more details about the implementation of the test statistics and the proceeding. As we are, to our knowledge, the first to comprehensively apply the approach, we lay out how applied econometricians can implement the proposed procedure.Footnote 12

The starting point of the procedure is to test whether there is a discontinuity in the relationship between the outcome variable and the forcing variable. In our application, this is testing for a discontinuity in the relationship of the probability to move to a switcher municipality and the moving date. We test

-

\(H_0^{(2)}\): no effects and selection only

-

\(H_1^{(2)}\): treatment effect only and both selection and treatment effect.

If \(H_{0}^{(2)}\) cannot be rejected, we abstain from further analysis as we are interested exclusively in cases where there is a treatment effect. According to the approach by Porter and Yu (2015), it can be assumed that there is a discontinuity in the relationship if \(H_{0}^{(2)}\) is rejected by the specification test. As the convergence rate of the derived test statistic (Tn) to a standard normal is slow, they propose approximating the finite-sample distribution by using the wild bootstrap of Wu (1986) and Liu (1988). The B bootstrap samples are generated by imposing the null hypothesis; i.e., such that they will mimic the null distribution of Tn. The null can be rejected if the value of the test statistic Tn exceeds the upper α-percentile of the resulting empirical distribution in the bootstrap sample \(T^{*}_{n(\alpha B)}\) (\(T_{n}>T_{n(\alpha B)}^{*}\)).

If \(H_{0}^{(2)}\), which implies that there is no discontinuity in the relationship, can be rejected by the specification test, the threshold value c and the discontinuity size τc (the LATE) can be estimated. The discontinuity point c is thereby determined by

and thus by checking whether c = xi (xi ∈π) maximizes \(\hat \tau ^{2}(c)\), where π is the search interval of the assignment variable.

The estimate of \(\hat \tau (c)\), i.e., the non-parametric estimate of the discontinuity in the relationship between y and x at c, is estimated as in the classical RDD literature. Importantly, Porter and Yu (2015) show that \(\hat \tau _{c}\) is a natural by-product of the estimation of the discontinuity point, and that c can be treated as if known when estimating treatment effects in RDDs. It is therefore not necessary to correct the inference for the fact that the threshold is an estimate itself, as the asymptotic distribution of \(\hat \tau (\hat c)\) is the same as if c was known. Thus, after the estimation of c, one can perform a standard RDD analysis.

For the point estimates in our analysis, we follow, e.g., Hahn et al. (2001), Porter (2003) and Imbens and Lemieux (2008) and estimate the limits by a local linear regression (LLR) of the form

using a uniform kernel, as in the specification testing.

A peculiarity of using moving dates as assignment variable is that it is necessary to control for periodical patterns before running the analysis (Davis 2008; Paola et al. 2012). We take these potential periodical patterns in moving dates into account by controlling for a battery of indicator variables, i.e., month, day of the month, and the weekday of the movement fixed effects. As often done in RDD studies, we first run a linear regression of the dependent variable on covariates. Subsequently, the residual of this regression is used as the dependent variable in our analysis (see, e.g., Lee and Lemieux 2010). For notational convenience, we will nonetheless refer to our dependent variable as yi or the probability that an individual moves to a switcher municipality.Footnote 13 For graphical representation, we plot a local linear regression of y over x using a rectangular kernel to gain an impression of the basic relationship and we present a series of validation checks for the identifying assumptions after presenting the results in Section 7.

5 Data

Our main empirical application draws on administrative data on the whole foreign population in Switzerland for the years between 2006 and 2011, which was kindly provided by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO) in cooperation with the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM). We thus rely on high quality data when it comes to individuals’ moving dates.Footnote 14 We restrict our estimation sample to be the universe of all foreigners in Switzerland holding either the residence permit B, for temporary residency, or C, for permanent residency. We thus exclude foreigners with other types of permits such as asylum seekers, who are not allowed to choose their location freely. We exclusively use data on individuals moving within Switzerland and thus exclude those just immigrating or leaving the country. Moving individuals are assigned to their destination canton. In total, this sample includes roughly 7,854,025 observations and 559,951 incidences of foreigners moving.

Further, we use data on municipality characteristics and voting outcomes. This data is freely available on the website of the Swiss Federal Statistical Office. Data on the municipality tax rates has been kindly provided by Parchet (2014).

6 Results

The results of our empirical analyses are presented in several steps. In a first step, we follow a simple approach using a linear probability model to test whether the location choices of individuals change systematically after the vote. We then proceed by presenting our main results of the proposed regression discontinuity approach, i.e., pooled estimates of those cantons for which a discontinuity is detected. In the following discussion section, we first validate that the change in the relative political position of switcher municipalities is relevant. Second, we test alternative supply-side explanations of the general phenomenon; i.e., landlords’ discriminatory behavior and labor market discrimination. Next, we report the results of the validation of the identifying assumptions of the RDD and perform a placebo test. Finally, we present some complementary evidence on the development of housing prices in switcher municipalities after the minaret vote.

The empirical analysis draws initially on data for 22 Swiss cantons.Footnote 15 We abstain from testing for a treatment effect in four cantons, namely the cantons of Uri, Obwalden, Appenzell-Innerrhoden, and Geneva. The former three cantons are rather small and, although we draw on register data, there are too few observations to perform the analysis. Furthermore, we exclude the canton of Geneva, since no municipality in this canton accepted the minaret initiative, and thus, there is no switcher municipality.

6.1 Results of a simple approach

In a preliminary analysis, we abstract from the reasoning about the time when the new information about attitudes is incorporated and reflected in moving dates and location choices, and simply study the probability of moving to a switcher municipality after the vote on the minaret initiative and test whether this probability declined in the months after the vote. We fit a linear probability model (OLS) to the observation that someone chooses to locate in a switcher municipality for individuals moving in the two years around the vote. As any effect might be observable for a limited amount of time only, for example, due to reactions on the housing market, we choose a flexible specification. Specifically, we estimate a specification including eight monthly indicators post. for up to 240 days after the vote. They show how the moving pattern evolves during the eight months after the vote. We further include one indicator for the period between 240 days up to one year after the vote. The coefficient of the latter variable post> 240 shows whether the probability to move to a switcher municipality is lower after the vote in the medium-term, i.e., after eight months. As mentioned before, we correct for possible periodical patterns in the moving behavior, by using the residual of a regression on month, day of month, and weekday indicators by canton as the dependent variable.

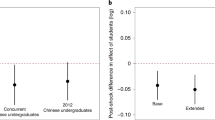

The results are presented in Table 1 and visualized in Fig. 3. Row (1), indicated by “Overall,” shows the model estimate for the 22 cantons in the sample. We observe systematic drops in the probability that foreigners move to a switcher municipality in the time frame between four and seven months after the vote. This is consistent with our main hypothesis and the time lag after the vote fits the institutional feature of a three months notice period in many rental contracts. The drop of around one percentage point amounts to a 7.7% decline vis-à-vis the fraction of about 13% of foreigners moving to switcher municipalities before the vote. Given the short-comings of the simple approach to identify behavioral reactions, a larger effect size is expected in the RDD.

These figures visualize the estimates presented in Table 1. Row (1) is shown on the left hand side and row (2) on the right hand side

6.2 Main estimates for observed location choices applying the regression discontinuity approach

In the main analysis, separate analyses are performed for each destination canton of movers as the threshold date might vary depending on the situation on the housing market and the institutional variation. The specification testsFootnote 16 detect a discontinuity in 12 cantons.Footnote 17 The corresponding results of the specification test are presented in Table 9 in Appendix 3. In Appendix 1, we perform an exemplary analysis for one canton, i.e., the canton of Thurgau, to show how the empirical strategy is applied. The null hypothesis of no effect is not rejected for the remaining ten cantons.Footnote 18 This does not necessarily exclude the possibility that foreigners in these cantons also reacted. However, the situation on the housing market or the incorporation of the new information might not have followed a pattern which would allow the applied method to capture the effect.

As we learned from the simulation, our identification strategy requires some form of rigidity in the rental market, for example a binding notice period, so that the control and the treatment group can be distinguished. While there is a legal default for a notice period of 3 months in rental agreements, actual moving dates (and related lease payments) are negotiable. So whether the notice period is binding or not depends to a large extent on whether the old tenant can find a new tenant. This might hold in a tight market, as well as in one where numerous people simultaneously want to change their domicile. If tenants intending to move have to wait until the end of their lease, a possible sign of market rigidity, this should be reflected in cumulated movements at the end of the month. The moving patterns within cantons could thus provide some indication about the situation on the rental market (see Figs. 11 and 12 in Appendix 4). While there are clear peaks in the share of moving individuals at the end of each month in many cantons, there are some cantons (LU, FR, BS, SH, and NE) for which no distinct periodical pattern is observed. For these latter cantons, also no discontinuity is detected. The situation on the housing market could thus be one consistent explanation for why we find discontinuities in some but not all the cantons.

For the 12 cantons with a discontinuity, we potentially are able to separate treated from untreated individuals and thus estimate the local average treatment effect.Footnote 19 While this provides us with a local estimate for the sample at hand, there is no obstacle for its causal interpretation.

If we again apply the former simple approach to a sample restricted to those cantons for which a discontinuity is detected, we find stronger drops in the four to seven months after the vote (see Table 1, row (2)). The estimated coefficients indicate that during this period the probability of moving to a switcher municipality went down by around 2 percentage points. The estimates are visualized in Fig. 3. No clear pattern is observed in the cantons where no discontinuity has been detected (see row (3)). The probability of moving to a switcher municipality seems to drop initially during the first month after the vote. However, it promptly returns to the old level. While these results provide further evidence that is consistent with our main hypothesis the procedure is still too rough to capture the full effect, primarily because the time indicators do not separate between treated and untreated individuals. Moreover, the effects likely do not materialize in all cantons at the same time, such that an averaging by month leads to an underestimation of the impact of the revelation of reservations towards foreigners. In the next sections, we therefore proceed with the proposed RDD approach at the detected threshold dates.

Overall effect at the threshold values

The main results build on a pooled analysis of the data of those cantons for which it is possible to estimate a discontinuity. The threshold dates are estimated to lie between about 1 and 5.5 months after the vote. For observations from each canton, we center the moving dates at the detected thresholds, such that the resulting threshold for the pooled results is at zero. Combining data for all moving foreigners, we represent the main finding in a RDD graph presented in Fig. 4.Footnote 20 A pronounced negative jump at the threshold is observed. Moreover, the probability of moving to a switcher municipality seems to return to its former level after some time.

Probability of moving to municipalities revealing stronger reservations against foreigners in the pooled sample of cantons. Local linear smooth of the probability that a foreigner moves to a switcher municipality separately from both sides of the threshold, and using a bandwidth of 45 days. The light gray dots represent raw means within bins of 5 days

Estimating the treatment effect at the threshold as described in Section 4, the estimated drop in the probability that a foreigner moves to a switcher municipality is about 4 to 8 percentage points, depending on the applied bandwidth.Footnote 21 The corresponding estimation results are presented in Table 2. The estimated effect is sizable. Before the threshold dates, the average probability that foreigners move to a switcher municipality was about 13%. The jump at the threshold of about 4 to 8 percentage points, thus amounts to a drop of about 30 to 60%.

Temporal development of the effect

As is evident from Fig. 4, the effect fades after some time. To gain an impression of how long the effect persists, we run a linear regression model including indicators for time periods after the break on the pooled data for a time span of half a year around the threshold dates. We estimate a model of the form

where y is our dependent variable, i.e., the residual of a regression of time fixed effects on an indicator set to one if an individual moves to a switcher municipality, xc is the moving date centered at the estimated threshold for the corresponding canton, and k ⋅ 30 stands for a number series rising in intervals of 30 days: {0, 30,...,180}. The γ. coefficients consequently indicate whether the probability of moving to a switcher municipality is different from the level before the break within the specified time span. The estimation results are presented in Table 3. Given that the average probability of moving to a switcher municipality before the break is about 12.5%, the initial decline within the first month amounts to about 40%. It turns out that the effect becomes weaker over time, as suggested by the graphical evidence. There is no systematic difference in the level anymore about 150 days, or 5 months, after the break. This leveling off could occur, because the issue is no longer salient, i.e., expressed attitudes are no longer being discussed in the media. Alternatively, or in some combination, the housing market could have adjusted to a new equilibrium in which foreigners are compensated by, for example, lower rents for their disutility of residing in a municipality in which attitudes towards them are more negative.

We find at least suggestive evidence that the latter adjustment channel is relevant in an additional analysis described in Section 8, where we try to assess whether housing prices in switcher municipalities decrease in the aftermath of the vote.

Effects for different groups of foreigners

The vote on the minaret initiative prohibited Muslim communities from constructing further minarets. The change in the substantive law was thus narrow and affected solely one particular group within the foreign population of Switzerland. However, the public discourse was much broader in that it addressed general concerns about migration, as well as the role of (religious) tolerance and cultural identity in Switzerland. Based on the content of the initiative, we would expect that foreigners, in particular those with a Muslim background, experience lower expected identity utility from moving to a municipality where the initiative had unexpectedly received wide support. However, due to the general discourse, the outcome of the vote might well have been perceived as a revelation of attitudes towards foreigners in general. According to our understanding of the event, we share such an interpretation. Moreover, identity theories predict that other (foreign) minority groups identify with the beleaguered minority group. Accordingly, similar effects for different groups of foreigners are expected. This reasoning is in line with the finding in Rudert et al. (2017), documenting that even foreigners, and in particular highly skilled foreigners, who are not directly affected by an anti-immigration vote in Switzerland in 2014 experienced considerable distress in regions where the support for this initiative was high.

In order to learn about any heterogeneity across groups of foreigners, we re-estimate the effect for various subsamples of foreigners. As the results in Table 4 show, we find systematic effects for foreigners holding either temporary or a permanent residence permit, for European and non-European foreigners, as well as for foreigners from Muslim countries.Footnote 22 This is evidence that the change in perceived attitudes affected the attractiveness of particular municipalities for the group of foreigners across nationalities and cultural backgrounds.

While the relative magnitude of the effect seems to be strongest for non-European foreigners, it is still considerable for European foreigners. Overall, according to our interpretation, the reaction was in response to the unexpectedly revealed negative perceptions of the native population. The comparatively large reaction of non-Muslims might thereby be rationalized along two lines of reasoning: First, it has not been equally easy (or it has been differentially costly) for all groups in the foreign population to react. Recently immigrated Muslims are often less well educated and economically less well off than other immigrants, such as work migrants from the rest of Europe. This latter group of people has relatively more resources (including information) to react in their location choice. Second, highly skilled individuals are more sensitive to reservations towards immigrants. However, there are fewer highly skilled individuals among the Muslim population in Switzerland. Both lines of reasoning would be consistent with the observation that all groups react to a rather similar extent.

Effects for foreigners with different occupational skill levels

So far, the evidence suggests that, in general, residents of Switzerland with a foreign nationality expected to experience a loss in utility if they were to move to a municipality that unexpectedly revealed increased reservations towards foreigners. However, the effects might differ depending on individuals’ skill level. Regarding foreigners with a low educational background, studies investigating the determinants of attitudes towards foreigners frequently argue that concerns about the welfare system play an important role (see, e.g., Hainmueller and Hiscox 2010; Dustmann and Preston 2007). Thus, immigrants with a low level of education, who are more likely to rely on the welfare system, might be the main targets of negative attitudes towards foreigners. It is, however, open whether they also experience the highest loss in identity utility when residing in an environment with strong reservations against foreigners. Instead, foreigners with a high education might be particularly sensitive towards such reservations. They might be more interested in politics and more likely to follow the discussion in the media than their less well educated compatriots (Rudert et al. 2017; Elsayed and De Grip 2018).

In our data, we have only limited information about the formal education of the individuals to test for differential effects across skill levels. Instead, we rely on information about individuals’ occupations. As the immigration authorities do not collect this information systematically, it is only available for about 15% of individuals in our data. We infer people’s (occupational) skill level by matching occupations to standards of required formal education. It is important to note that immigrants work in occupations that do not match their skill level more often than nationals. Their formal educational degrees might not be accepted. This might be especially the case for, for example, refugees from developing countries. Miscategorizations are therefore likely in particular for people in occupations with formally low skill requirements. To mitigate this miscategorization problem we use only individuals originating from countries from which formal education is most likely accepted in Switzerland. These are the countries of the European-Union and countries on the American continent, as the United States, Canada, and Brazil. We further include Australia, and New Zealand. Concentrating on these individuals, we expect that occupation is a good approximation of the skill level.

We use the ISCO-08 classification of the International Labour Office (2012) to classify the skill level needed to perform specific occupations. The four-point classification considers not only required formal education, but also the task complexity of the respective occupation. We differentiate between high, upper-medium, medium, and low skilled individuals.Footnote 23

The number of observations in this sample get scarce. Nonetheless, we can interpret the results, presented in Table 5, qualitatively. We find that within this sample of nationalities the high-skilled group is most sensitive to the revelation of new information about citizens’ attitudes towards foreigners. The estimate is significantly different from zero despite the few observations. For the other groups, the discontinuity estimates seem to fall the lower the skill level. However, the estimates for these other groups are not significantly different from zero at conventional levels. These results suggest that the group of high-skilled immigrants seems to react the most.

7 Discussion

This section contains a discussion of potential challenges to the causal interpretation of our results and two alternative explanations behind the documented effect, as well as the validation for the assumptions behind our empirical approach.

7.1 Validation check for the relevance of the change in the relative political positioning of the switcher municipalities

The definition of the switcher municipalities results in a dichotomous categorization of municipalities. Accordingly, we see per construction an equivalent positive jump in the probability of moving to a non-switcher municipality at the threshold, as we saw a negative one in the probability to move to a switcher municipality. The corresponding pattern is presented in Fig. 5. RDD estimation results are reported in Table 11 in columns 1, 2, and 3 in Appendix 4. Moreover, the classification itself rests on a central argument emphasizing that the voters in a switcher municipality not only expressed a more restrictive position towards migration than in the past, but that the swing in expressed reservations is also more pronounced than for the average municipality of a canton (second condition of the definition for switcher municipalities outlined in Section 2.2). In order to validate the importance of this rank condition, i.e., the fact that it is the relative position within the choice set that matters, we re-estimate the basic specifications with the pooled data for an alternative classification of municipalities. We construct the dependent variable such that it captures the probability of moving to a municipality that has not changed its rank, i.e., its position regarding the support of critical attitudes towards foreigners compared to the other municipalities in the canton. Specifically, we focus on municipalities that are not switcher municipalities and have not experienced a rank change. If our findings were driven by a change in the positioning, we would not expect to see a pronounced jump, either positive or negative, in the probability of moving to these municipalities at the estimated thresholds. The resulting pattern is presented graphically in Fig. 5b. The results of the RDD estimates are reported in Table 11 in columns 4, 5, and 6 in Appendix 4. We do not find a systematic reaction for this category of municipalities.

Probability of moving to alternative groups of municipalities. Local linear smooth of the probability that a foreigner moves to a specific group of municipalities separately from both sides of the threshold, and using a bandwidth of 45 days. The light gray dots represent raw means within bins of 5 days

In an additional test, we analyze whether the positive jump within the group of non-switcher municipalities is consistent with our reasoning. We define two further alternative groups of municipalities, one including non-switcher municipalities with a positive rank change, and thus a relative right shift, after the vote on the minaret initiative and one including non-switcher municipalities with a negative rank change, and thus a relative left shift. Re-estimating the jump in the probability of moving to one of these municipality types at the threshold, we find that the positive jump in the non-switcher municipalities seems to be driven by municipalities with a negative rank change. The estimation results can be found in Table 11, columns 7 to 12 in Appendix 4. This finding is consistent with our reasoning that foreigners are deterred from moving to municipalities revealing reservations, and rather choose to move to municipalities that got relatively more attractive in this dimension.

We interpret this as further support that the observed negative jump in the probability of choosing a switcher municipality is driven by a mover’s perception of an unexpected negative shift in the social attitudes of these municipalities towards foreigners.

7.2 Two alternative supply side explanations

So far, the empirical regularity is interpreted within the theoretical framework based on demand-side reactions to perceived negative attitudes. However, the observed patterns in aggregate moving behavior across municipalities would also be consistent with supply-side reactions. First, native landlords in switcher municipalities might feel free to discriminate against foreigners, once they are informed about their co-residents’ attitudes towards immigrants. If this supply-driven explanation holds, native landlords are expected to discriminate against foreigners in general. When considering second-generation immigrants who hold the same foreign names, the same potentially foreign appearance, and the same residence permit types as their parents, one would thus expect landlords to also—at least to some extent—discriminate against this group of foreigners. However, if the phenomenon is primarily demand-driven, a smaller reaction is expected for the second-generation immigrants, as they are in general better assimilated. They grew up in the Swiss institutional environment, for example, being familiar with referendums on migration issues. We are aware though that this is not a clear-cut test as discrimination might be based on characteristics along which first- and second-generation immigrants differ. The test thus loses bite if, for example, due to language skills first-generation and second-generation migrants are differentially discriminated against. To explore differential reactions, we repeat our estimates for the group of second-generation foreigners, i.e., individuals who were born in Switzerland but have not been naturalized. Table 6 reports the estimates of the treatment effect. We find a much smaller reaction for second-generation foreigners, whereby no statistically significant treatment effect is estimated. Together with the preceding finding that highly skilled foreigners react the most, this suggests to us that the main effect is primarily demand-driven. The highly skilled (well-payed) foreigners are likely the more attractive tenants for landlords than the less skilled foreigners, so in case of discrimination we would expect to see the largest reactions for this latter group.

A second potential supply-side explanation focuses on the labor market. After the ballot, employers in switcher municipalities might feel free to discriminate against foreign labor, discouraging immigrants from moving into these municipalities. In order to test this explanation, we analyze relocations in narrow neighborhoods, as they are less likely to be due to a job change. Thus, if the effect were driven by labor market discrimination, we would expect relocations within a narrow radius to be less affected. If, however, the effect is, as we argue, due to the perceived change in attitudes, we would expect the effect to also be present in movement patterns within a narrow radius. To implement this test, we repeat our estimates for a subsample of foreigners who move within a narrow radius. The distance between the old and the new municipality of residence is measured in minutes of travel time, and we use 15 minutes as a measure of relatively short distance.Footnote 24 The results reported in Table 7 show that the effect for this subsample of individuals who move within a 15-min radius is very similar to the baseline effect. If anything, it is slightly stronger. A stronger effect within a narrow radius seems sensible given that it is less costly to get the information about vote outcomes in the direct surrounding. The observation that individuals who move within a narrow radius, probably not attributable to a job change, are just as likely to react as those who move within a wider radius leads us to the conclusion that labor discrimination most likely cannot explain our finding.

7.3 Validation of the identification assumptions

There are some crucial assumptions that need to hold for a valid RDD setting. In our setting, they translate to the assumptions that individuals deciding where to move before or after the vote are on average the same and that the characteristics of switcher municipalities, except for their voting behavior, have not changed systematically. There is no formal test for this assumption and we do not observe the date of the moving decision. However, most RDD studies check whether individual characteristics are balanced around the threshold to validate it. We, in a first step, follow this strategy and estimate a sharp RDD, taking some individual characteristics, which are available in our data (i.e., age, civil status, duration of stay in CH, citizenship of parents, and individuals’ skill level), as dependent variables and using the estimated threshold date as threshold value. We report the results of this exercise in Table 12 in Appendix 4. We find only one significant estimate for age and a bandwidth of 45 days. As it is not robust to the bandwidth choice and seems to be rather small we are not alarmed that our results might be driven by this difference. We do not find systematic differences in the other individual characteristics around the threshold.

We secondly test, whether the characteristics of the switcher municipalities have not changed systematically after the vote in 2009. Table 13 in Appendix 4 reports the results of the corresponding validation estimates. While most characteristics have not systematically changed, we find evidence for two systematic changes: on the one hand, there is a decrease in the resident population, and on the other hand, there is a slight increase in the rate of vacant apartments in switcher municipalities. Both findings are rather complementary evidence in support of our main hypothesis, as they are consistent with the observed individual reactions of foreigners. It can be expected that there will be, at least temporarily, more vacant apartments if a sizable group of the population shuns switcher municipalities. When we study the number of Swiss and foreign residents separately, we find that the point estimate is larger for foreigners. The reduction in the number of Swiss citizens in switcher municipalities further suggests that there might be a group of Swiss citizens that reacts to the newly revealed information as well. This effect might be driven by naturalized immigrants, who we do not observe in our data, or by native citizens, who care about their neighbors’ attitudes in this dimension. Overall, the observation suggests some form of general preference-based spatial sorting. While it would be interesting to investigate the individual reactions for Swiss citizens in a separate analysis, corresponding individual level data for Swiss citizens is not available.