Abstract

Objectives

A number of studies have hypothesized that vitamin D is a potential factor in the prevention of falls in the elderly; however, the effect of vitamin D is still inconsistent and not quantitative. We conducted this meta-analysis to assess the effect of vitamin D on falls among elderly individuals.

Methods

The PubMed and Cochrane Library databases were searched from the earliest possible year up to December 2016. Two authors working independently reviewed the trials, and odds ratios (ORs) were calculated using a fixed-effect or random-effect model by Review Manager 5.3. We included only double-blind randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) of vitamin D in elderly populations that examined fall results.

Results

A total of 26 articles were included in which 16,540 elderly individuals received vitamin D supplementation, while 16,146 were assigned to control groups. The meta-analysis showed that combined vitamin D plus calcium supplementation has a significant effect on the reduction in the risk of falls (OR for the risk of suffering at least one fall, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.80–0.94). However, no significant association between vitamin D2 or D3 and a reduction in the risk of falls was found (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.58–1.03 for vitamin D2, and OR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.98–1.20 for vitamin D3).

Conclusions

Combined calcium plus vitamin D supplementation is statistically significantly associated with a reduction in fall risks across various populations.

Zusammenfassung

Zielsetzung

In zahlreichen Studien wurde spekuliert, dass Vitamin D ein potenzieller Faktor in der Sturzprävention bei älteren Menschen ist. Der Effekt ist jedoch weiterhin widersprüchlich und nicht quantifiziert. In der vorliegenden Metaanalyse haben wir den Einfluss von Vitamin D auf Stürze bei älteren Menschen untersucht.

Methoden

Die Datenbanken PubMed und Cochrane Library wurden vom frühesten erfassten Jahr bis Dezember 2016 durchsucht. Zwei Autoren sichteten unabhängig die Studien. Unter Anwendung von Review Manager 5.3 wurden mit einem Fixed-effects- oder Random-effects-Modell Odds Ratios (OR) berechnet. Einschluss in die Analyse fanden nur doppelblinde, randomisierte, kontrollierte Studien (RCT), in denen Vitamin D in Populationen älterer Menschen eingesetzt und Sturzergebnisse ausgewertet wurden.

Ergebnisse

Insgesamt wurden 26 Beiträge eingeschlossen, in denen 16.540 ältere Menschen eine Vitamin-D-Supplementierung erhielten und 16.146 Personen Kontrollgruppen zugeteilt waren. Wie die Metaanalyse ergab, hat die kombinierte Vitamin-D- und Kalziumsupplementierung einen signifikanten Effekt auf die Reduktion des Sturzrisikos (OR für das Risiko, mindestens einen Sturz zu erleiden 0,87; 95%-Konfidenzintervall [KI] 0,80–0,94). Dagegen fand sich keine signifikante Assoziation zwischen Vitamin D2 oder D3 und einer Reduktion des Sturzrisikos (für Vitamin D2: OR 0,77; 95%-KI 0,58–1,03; für Vitamin D3: OR 1,08; 95%-KI 0,98–1,20).

Schlussfolgerungen

Die kombinierte Vitamin-D- und Kalziumsupplementierung ist über verschiedene Populationen hinweg statistisch signifikant mit einer Reduktion des Sturzrisikos assoziiert.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Older adults have a high risk of falls [1]. Each year, one in three community-dwelling individuals aged 65 and older experiences at least one fall, and this percentage increases with age [2]. Fall-related fractures and injuries are a serious problem affecting quality of life and are a major cause of hospitalization and death in older persons [3]. Therefore, safe, feasible, effective, and cost-effective primary prevention measures are needed to reduce falls in older men and women. Multifactorial approaches, such as medical and occupational therapy assessments or adjustments in medications, behavioral instructions, and exercise programs reduce falls. However, they are expensive, take considerable time to implement, and are strongly dependent on the compliance of subjects. Vitamin D deficiency is common in the elderly [4, 5]. Many studies have demonstrated an association between vitamin D deficiency and falls. Vitamin D supplementation has been shown to improve muscle strength, function, and balance [6]. There is a meta-analysis in healthy subjects supporting the beneficial effects of vitamin D supplementation on falls [7]. Nevertheless, there is also a review suggesting that the evidence that vitamin D supplementation improves physical performance in older people is insufficient [8], and several randomized, controlled trials demonstrated that vitamin D did not reduce the number of falls. Therefore, since the potential effect of vitamin D on falls is inconsistent, it is necessary to establish whether vitamin D supplementation has a beneficial effect on falls in older adults.

In addition, maintaining calcium intake has long been recommended in older individuals to treat and prevent osteoporosis [9, 10]. Vitamin D combined with calcium supplementation affects calcium homeostasis and increases muscle strength. These benefits translate into a reduction in falls. Therefore, we hypothesized that the effect of vitamin D supplemented with calcium on the reduction in falls may be different compared to vitamin D supplementation alone. Above all, we conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the effect of vitamin D, administered either alone or in combination with calcium, on falls in older adults.

Methods

Data sources and searches

We systematically searched literature databases including PubMed and the Cochrane Library through December 2016 by using the following search terms: (randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial OR random allocation) AND (vitamin D OR cholecalciferol OR hydroxycholecalciferol OR calcifediol OR ergocalciferol OR calcidiol OR 25-hydroxyvitamin D OR 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D OR calcitriol OR alfacalcidol OR paricalcitol OR calcium) AND fall. Search terms were used in various combinations to maximize search results. The reference lists from articles identified in the database searches were examined to identify potentially relevant investigations. Manual searches complemented the number of potential articles. After removing duplicated articles, each title and abstract for potential inclusion was screened by two reviewers independently. Studies that reported odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) or cross-table data were included. If the article was potentially eligible for inclusion, the full text was examined by two independent reviewers. Any disagreement in study selection and data collection was discussed by the two reviewers. A total of 26 studies were found to fit the criteria.

Meta-analysis needs to meet the following criteria: Considerring any type of falls, including recurrent (falls ≥2 over the study period) and injurious falls. Falls were defined as ‘unintentionally coming to rest on the ground, floor, or other lower level’. Older adults (mean age ≥60 years) dwelling both inside and outside of hospital. We included only double-blind RCTs that studied any type of vitamin D. Case reports and series of course were of course excluded. We also excluded reviews focussing solely on specialist populations (Parkinson’s disease, e.g. stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, myasthenia gravis) in order to increase homogeneity.

Data extraction

Two review authors working independently and in parallel assessed the full texts of included studies. The following characteristics of each study were extracted: first author, year, sample size, mean age, treatment, vitamin D dose (IU/day), and study duration.

Definitions

Our primary outcome measure was the relative risk of having at least one fall among older individuals receiving vitamin D compared with those not receiving vitamin D. Falls were recorded by the nurses or the patients themselves in a fall diary.

Data analysis

The heterogeneity of results between studies was determined by I2. For I2, values of 25% to <50% were considered low heterogeneity, 50% to <75% moderate, and ≥75% highly heterogeneous. A random-effect model was used when there was heterogeneity in the meta-analysis (I2 > 50%), otherwise a fixed-effect model was applied for the meta-analysis. Together with I2 values, 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each I2 value. Tests for overall effect (Z score) were regarded significant at P < 0.05.

We conducted subgroup analysis to determine whether study conclusions were affected by the type of vitamin D-raising intervention (D2 vs. D3) or calcium co-administration status (vitamin D vs. vitamin D + calcium). To provide a comparison between outcomes reported by the studies, odds ratios and associated 95% confidence intervals were performed from each study and graphs created using Review Manager 5.3. OR values under 1.00 were associated with a decreased risk for falls as a result of the vitamin D-raising intervention.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

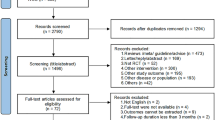

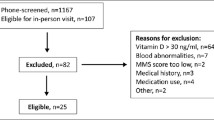

Our literature search identified 488 records, 33 of which were reviewed as full-text articles for inclusion. After further exclusions based on our selection criteria, 26 provided sufficient information for data extraction and were deemed suitable for our final analysis (Fig. 1). In total, these randomized controlled trials included 32,686 older adults; 16,540 received vitamin D intervention and 16,146 were assigned to control groups (Table 1). The mean age ± SD of participants in these studies varied from 67 ± 2 to 92 ± 6 years. Study sizes ranged from 64 to 9440 participants, with the duration of follow-up ranging from 1 month to 60 months. The evaluated dose of vitamin D ranged from 200 IU/day VD2 to 1000 IU/day VD2; in 11 of the 26 studies the dosage was 800 IU/day, six studies used a total dosage ranging from 300,000 IU/36 months VD2 to 600,000 IU/6 months VD2. In the studies conducted by Bischoff-Ferrari et al. [7, 11, 12], Grant et al. [13], Burleigh et al. [14], Flicker et al. [15], Prince et al. [16], Pfeifer et al. [17], Kärkkäinen et al. [18], Neelemaat et al. [19], Berggren et al. [20], Larsen et al. [21], Harwood et al. [22], and Chapuy et al. [23], vitamin D was supplemented in combination with calcium in older adults. Other studies were supplemented with vitamin D2 or D3 alone.

In the study conducted by Grant et al. [13], participants were randomly allocated to four equal groups and assigned two tablets with meals daily consisting of 800 IU vitamin D3, 1000 mg calcium (given as carbonate), vitamin D3 (800 IU) combined with calcium (1000 mg), or placebo. In group 1, participants received vitamin D and calcium. In group 2, participants received vitamin D alone. Since the participants were different in the two groups, we regarded the two groups as two independent studies. In the study conducted by Broe et al. [31], vitamin D was supplemented in different doses; again, we regarded the two groups as two independent studies.

All studies included were examined for heterogeneity; the heterogeneity of all studies was determined to be low: P < 0.001, I2 = 79% for vitamin D2, P = 0.130, I2 = 42% for vitamin D3, and P = 0.030, I2 = 46% for vitamin D plus calcium. Accordingly, a random-effect model and a fixed-effect model were applied for further meta-analysis.

Main outcomes

The effects of vitamin D2 supplementation on falls in the studies included are shown in Fig. 2. We found no significant association between vitamin D2 and a reduction in the risk of falls (OR for the risk of suffering at least one fall, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.58–1.03; I2 = 79%; Fig. 2).

The effects of vitamin D3 supplementation on falls in the studies included are shown in Fig. 3. We found no significant association between vitamin D3 and a reduction in the risk of falls (OR for the risk of suffering at least one fall, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.98–1.20; I2 = 42%; Fig. 3).

The effects of vitamin D combined with calcium supplementation on falls for the included studies are shown in Fig. 4. We found a significant association between vitamin D combined with calcium supplementation and a reduction in the risk of falls (OR for the risk of suffering at least one fall, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.80–0.94; I2 = 46%; Fig. 4).

For the eight RCTs comparing vitamin D with controls, individual and pooled mean differences for the eight outcome measures are shown in Fig. 5. According to Fig. 5, vitamin D treatment significantly increased the pooled mean values for serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D compared with control treatment (MD, 10.04; 95% CI, 1.53–18.55; I2 = 100%).

Among the three RCTs, vitamin D treatment significantly increased the pooled mean values for serum 1, 25-hydroxyvitamin D compared with control treatment (MD, 7.23; 95% CI, 0.21–14.25; I2 = 89%; Fig. 6).

Discussion

We conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the best available research evidence regarding the effect of vitamin D on falls. This meta-analysis included 26 articles with 16,540 elderly individuals treated with different vitamin D analogues for 2 months up to 3 years. In all of these trials, the method of fall ascertainment and fall definitions were specified. Participants included healthy individuals living in the community, as well as hospital inpatients. Evidence suggested that a reduction in the risk of falls depends on the type of vitamin D supplementation. We found a statistically significant reduction in the risk of falls in the sub-analyses of vitamin D combined with calcium supplementation on the risk of falls. The pooled results found a statistically significant 6% reduction in the risk of falling with vitamin D combined with calcium compared with the control group. However, there is no significant association between vitamin D2 or D3 supplementation and falls.

Although vitamin D is used to prevent falls, the current evidence for an effect of supplementary vitamin D alone on fall outcomes is limited and conflicting. There continues to be evidence suggesting that vitamin D alone has no effect on reducing the risk of falls. In the study conducted by Latham et al., the vitamin D intervention was given in a single oral dose. Patients received 300,000 IU vitamin D3. However, there was no effect of vitamin D3 supplementation on physical function in older people, even in those patients with low 25-OH-D levels [36]. The largest population-based, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial found that an annual i. m. injection of 300,000 IU vitamin D2 had no effect in preventing falls when compared with placebo [32]. What is more, Sanders et al. even found a contrasting result: the participants receiving annual high-dose oral cholecalciferol experienced 15% more falls than the placebo group [33]. In line with these studies, no significant association between vitamin D2 or D3 supplementation and falls was found in this meta-analysis. However, our results indicate that a vitamin D supplement is able to significantly increase serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and serum 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels in the elderly. Previous studies also showed that serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels are associated with quadriceps strength and balance.

Older people are recommended to take at least 1000–1200 mg/day of calcium to treat and prevent osteoporosis [37]. There is increasing evidence to suggest that vitamin D combined with calcium produces a beneficial effect on falls. According to previous studies and meta-analyses, the combination of calcium with vitamin D is important for fall prevention [38]. An earlier study by Bischoff et al. reported a 49% reduction in falls during a 3‑month intervention with 800 IU vitamin D and 1200 mg calcium [26]. A meta-analysis showed that vitamin D and calcium supplementation reduced the falls risk by 21% [39]. Calcium intake is significantly lower in developing countries due to the deficient use of dairy products. Vitamin D together with calcium is the recommended combination for achieving health benefits. Increasing calcium intake either by dietary sources or supplements has beneficial effects on bone density. Specifically, a single intervention with vitamin D plus calcium over a 3-month period reduced the risk of falling by 49% and significantly improved musculoskeletal function compared with calcium alone in older adults [26]. Similarly, vitamin D plus calcium compared with calcium alone improved quadriceps strength by 8% and decreased body sway by 9% within 2 months in elderly women [25]. It is well known that vitamin D promotes calcium absorption and helps to maintain adequate serum calcium concentrations to enable normal bone mineralization. Thus, calcium and vitamin D work together synergistically on the bone, and the results of our meta-analysis support their combined use to reduce fall risk.

Safety

Although quantitative safety data of vitamin D supplementation in humans has not been reported definitively, a number of studies have found no adverse side effects in humans. In fact, the majority of these studies indicate that vitamin D is safe. The optimal dose of vitamin D is currently not conclusive: most studies advise taking 800 IU of vitamin D daily for the maximum benefit. The consumption of vitamin D in dosages as high as 1000 IU/day was not found to have any side effects in humans. Along with determining an optimal dose, the long-term safety of vitamin D supplementation in older adults needs to be assessed.

Limitations and strengths

A publication bias has likely affected the results presented in this review. The dietary sources of vitamin D represent a co-intervention that could introduce noise to the signal produced by the intervention in unblended studies and may bias the results toward the null. The strengths of this review stem from the extensive literature search, the protocol-driven, reproducible nature of the review, and the use of bias protection measures such as reviewing articles and data extraction by blinded pairs of reviewers.

Conclusions

In summary, combined calcium plus vitamin D supplementation is statistically significantly associated with reduced fall risks across various populations.

Abbreviations

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- OD:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- MD:

-

Mean deviation

- VD2:

-

Vitamin D2

- VD3:

-

Vitamin D3

References

Rubenstein LZ (1997) Preventing falls in the nursing home. JAMA 278:595–596

Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF (1988) Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N Engl J Med 319:1701–1707

Ray WA, Taylor JA, Brown AK, Gideon P, Hall K, Arbogast P, Meredith S (2005) Prevention of fall-related injuries in long-term care: a randomized controlled trial of staff education. Arch Intern Med 165:2293–2298

Smith G, Wimalawansa SJ, Laillou A, Sophonneary P, Un S, Hong R, Poirot E, Kuong K, Chamnan C, De Los Reyes FN, Wieringa FT (2016) High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in cambodian women: a common deficiency in a sunny country. Nutrients. doi:10.3390/nu8050290

Chalmers J (1991) Vitamin D deficiency in elderly people. BMJ 303:314–315

Tang BM, Eslick GD, Nowson C, Smith C, Bensoussan A (2007) Use of calcium or calcium in combination with vitamin D supplementation to prevent fractures and bone loss in people aged 50 years and older: a meta-analysis. Lancet 370:657–666

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Willett WC, Staehelin HB, Bazemore MG, Zee RY, Wong JB (2004) Effect of Vitamin D on falls: a meta-analysis. JAMA 291:1999–2006

Latham NK, Anderson CS, Reid IR (2003) Effects of vitamin D supplementation on strength, physical performance, and falls in older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 51:1219–1226

Consensus conference (1984): Osteoporosis.[J].JAMA: The journal of the American Medical Association 252(6):799–802

Ross AC (2011) The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Public Health Nutr 14:938–939

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Conzelmann M, Stahelin HB, Dick W, Carpenter MG, Adkin AL, Theiler R, Pfeifer M, Allum JH (2006) Is fall prevention by vitamin D mediated by a change in postural or dynamic balance? Osteoporos Int 17:656–663

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Orav EJ, Dawson-Hughes B (2006) Effect of cholecalciferol plus calcium on falling in ambulatory older men and women: a 3-year randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 166:424–430

Grant AM, Avenell A, Campbell MK, McDonald AM, MacLennan GS, McPherson GC, Anderson FH, Cooper C, Francis RM, Donaldson C, Gillespie WJ, Robinson CM, Torgerson DJ, Group RT (2005) Oral vitamin D3 and calcium for secondary prevention of low-trauma fractures in elderly people (Randomised Evaluation of Calcium Or vitamin D, RECORD): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 365:1621–1628

Burleigh E, McColl J, Potter J (2007) Does vitamin D stop inpatients falling? A randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 36:507–513

Flicker L, MacInnis RJ, Stein MS, Scherer SC, Mead KE, Nowson CA, Thomas J, Lowndes C, Hopper JL, Wark JD (2005) Should older people in residential care receive vitamin D to prevent falls? Results of a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 53:1881–1888

Prince RL, Austin N, Devine A, Dick IM, Bruce D, Zhu K (2008) Effects of ergocalciferol added to calcium on the risk of falls in elderly high-risk women. Arch Intern Med 168:103–108

Pfeifer M, Begerow B, Minne HW, Suppan K, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Dobnig H (2009) Effects of a long-term vitamin D and calcium supplementation on falls and parameters of muscle function in community-dwelling older individuals. Osteoporos Int 20:315–322

Karkkainen MK, Tuppurainen M, Salovaara K, Sandini L, Rikkonen T, Sirola J, Honkanen R, Arokoski J, Alhava E, Kroger H (2010) Does daily vitamin D 800 IU and calcium 1000 mg supplementation decrease the risk of falling in ambulatory women aged 65–71 years? A 3‑year randomized population-based trial (OSTPRE-FPS). Maturitas 65:359–365

Neelemaat F, Lips P, Bosmans JE, Thijs A, Seidell JC, van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA (2012) Short-term oral nutritional intervention with protein and vitamin D decreases falls in malnourished older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 60:691–699

Berggren M, Stenvall M, Olofsson B, Gustafson Y (2008) Evaluation of a fall-prevention program in older people after femoral neck fracture: a one-year follow-up. Osteoporos Int 19:801–809

Larsen ER, Mosekilde L, Foldspang A (2005) Vitamin D and calcium supplementation prevents severe falls in elderly community-dwelling women: a pragmatic population-based 3‑year intervention study. Aging Clin Exp Res 17:125–132

Harwood RH, Sahota O, Gaynor K, Masud T, Hosking DJ, Nottingham Neck of Femur S (2004) A randomised, controlled comparison of different calcium and vitamin D supplementation regimens in elderly women after hip fracture: The Nottingham Neck of Femur (NONOF) Study. Age Ageing 33:45–51

Chapuy MC, Pamphile R, Paris E, Kempf C, Schlichting M, Arnaud S, Garnero P, Meunier PJ (2002) Combined calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation in elderly women: confirmation of reversal of secondary hyperparathyroidism and hip fracture risk: the Decalyos II study. Osteoporos Int 13:257–264

Graafmans WC, Ooms ME, Hofstee HM, Bezemer PD, Bouter LM, Lips P (1996) Falls in the elderly: a prospective study of risk factors and risk profiles. Am J Epidemiol 143(11):1129–1136. PMID: 8633602

Pfeifer M, Begerow B, Minne HW, Abrams C, Nachtigall D, Hansen C (2000) Effects of a short-term vitamin D and calcium supplementation on body sway and secondary hyperparathyroidism in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res 15:1113–1118

Bischoff HA, Stahelin HB, Dick W, Akos R, Knecht M, Salis C, Nebiker M, Theiler R, Pfeifer M, Begerow B, Lew RA, Conzelmann M (2003) Effects of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on falls: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res 18:343–351

Trivedi DP, Doll R, Khaw KT (2003) Effect of four monthly oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) supplementation on fractures and mortality in men and women living in the community: randomised double blind controlled trial. BMJ 326(7387):469. PMID: 12609940; PMCID: PMC150177

Dhesi JK, Jackson SH, Bearne LM, Moniz C, Hurley MV, Swift CG, Allain TJ (2004) Vitamin D supplementation improves neuromuscular function in older people who fall. Age Ageing 33(6):589–595. PMID: 15501836

Sato Y, Iwamoto J, Kanoko T, Satoh K (2005) Low-dose vitamin D prevents muscular atrophy and reduces falls and hip fractures in women after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Cerebrovasc Dis 20(3):187–192. PMID: 16088114

Law M, Withers H, Morris J, Anderson F (2006) Vitamin D supplementation and the prevention of fractures and falls: results of a randomised trial in elderly people in residential accommodation. Age Ageing 35(5):482–486. PMID: 16641143

Broe KE, Chen TC, Weinberg J, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Holick MF, Kiel DP (2007) A higher dose of vitamin D reduces the risk of falls in nursing home residents: a randomized, multiple-dose study. J Am Geriatr Soc 55:234–239

Smith H, Anderson F, Raphael H, Maslin P, Crozier S, Cooper C (2007) Effect of annual intramuscular vitamin D on fracture risk in elderly men and women – a population-based, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 46:1852–1857

Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Williamson EJ, Simpson JA, Kotowicz MA, Young D, Nicholson GC (2010) Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 303:1815–1822

Witham MD, Dove FJ, Dryburgh M, Sugden JA, Morris AD, Struthers AD (2010) The effect of different doses of vitamin D(3) on markers of vascular health in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 53(10):2112–2119. doi:10.1007/s00125-010-1838-1. PMID: 20596692

Glendenning P, Zhu K, Inderjeeth C, Howat P, Lewis JR, Prince RL (2012) Effects of three-monthly oral 150,000 IU cholecalciferol supplementation on falls, mobility, and muscle strength in older postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res 27(1):170–176. doi:10.1002/jbmr.524. PMID: 21956713

Latham NK, Anderson CS, Lee A, Bennett DA, Moseley A, Cameron ID, Fitness Collaborative G (2003) A randomized, controlled trial of quadriceps resistance exercise and vitamin D in frail older people: the Frailty Interventions Trial in Elderly Subjects (FITNESS). J Am Geriatr Soc 51:291–299

Hansson T, Roos B (1987) The effect of fluoride and calcium on spinal bone mineral content: a controlled, prospective (3 years) study. Calcif Tissue Int 40:315–317

Weaver CM, Alexander DD, Boushey CJ, Dawson-Hughes B, Lappe JM, LeBoff MS, Liu S, Looker AC, Wallace TC, Wang DD (2016) Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and risk of fractures: an updated meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporos Int 27:367–376

Murad MH, Elamin KB, Abu Elnour NO, Elamin MB, Alkatib AA, Fatourechi MM, Almandoz JP, Mullan RJ, Lane MA, Liu H, Erwin PJ, Hensrud DD, Montori VM (2011) Clinical review: the effect of vitamin D on falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:2997–3006

Funding

Key program of Clinical Specialty Disciplines of Ningbo (2013-88), Hua-Mei foundation (2017HMKY17)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

H. Wu and Q. Pang declare that they have no competing interests.

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Pang, Q. The effect of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on falls in older adults . Orthopäde 46, 729–736 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00132-017-3446-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00132-017-3446-y