Abstract

Purpose

The association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms is well-established, but the role of coping style in this association is less clear. We examined whether problem-focused, emotion-focused or avoidant coping style mediated and/or moderated the association in young adults.

Methods

Data were drawn from a 20-year longitudinal study that included 1294 students’ age 12–13 years recruited in 1999–2000 from ten high schools in Montreal, Canada. Herein we report an analysis that included 782 participants aged 24 years on average with data on covariates collected at age 20. Using VanderWeele’s four-way decomposition approach, the total effect of stressful life events on depressive symptoms considering coping styles was decomposed into four components: moderation only, mediation only, mediated interaction, no mediation or moderation.

Results

We observed mediation only by emotion-focused coping (\(\widehat{\beta }\)(95%CI) = 0.15(0.04, 0.24)) suggestive that individuals who experienced more stressful life events also reported greater use of emotion-focused coping and higher levels of depressive symptoms. We found moderation only by problem-focused coping (\(\widehat{\beta }\)(95%CI) = − 1.51(− 2.40, − 0.53)) and by emotion-focused coping (\(\widehat{\beta }\)(95%CI) = 1.16(0.57, 1.69). These results suggest that individuals reporting more problem-focused coping experienced fewer depressive symptoms after exposure to stressful life events; those reporting more emotion-focused coping experienced more depressive symptoms. Avoidant coping did not mediate or moderate the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

Interventions that aim to reduce depressive symptoms in young adults who experience stressful life events may need to reinforce problem-focused coping and minimize emotion-focused coping strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Canada in 2019, one-quarter of post-secondary students reported feeling very sad and 21% reported difficulty functioning due to their depressed mood in the past 12-months [1]. Experiencing depressive symptoms can have negative impact on academic performance [2], personal relationships, social life [3], work performance [4], as well as future depression and overall quality of life.

Stressful life events are a risk factor commonly associated with depressive symptoms [5], and specific stressful life events or conditions including illness [6], trouble with family members [6], death of a family member or parental separation [7], and peer pressure or problems with friends [8] are strongly associated with depressive symptoms. Although life events can occur at any time during the life course, the transition from adolescence to young adulthood is a challenging life stage often characterized by important changes such as beginning university, entering the workforce, and establishing long-term relationships [9]. Because many stressful events occur during this developmental phase and since depressive symptoms are prevalent in youth and are associated with an increased risk of major depression and functional impairment [10], investigations to better understand the mechanisms underpinning the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms in young adults are needed. Importantly, better knowledge in this domain could guide preventive interventions aimed at reducing depressive symptoms in young adulthood.

Not all individuals exposed to stressful life events develop depressive symptoms, suggestive that other factors underpin this association. The transactional theory of stress and coping [11] posits that when a life event occurs, an individual cognitively appraises the situation by assessing whether it is threatening, harmful or challenging (i.e., stressful). During this cognitive process, the individual assesses whether and how the situation can be dealt with, which may invoke a coping strategy [11]. Coping style refers to the general approach and use of specific strategies that individuals employ to deal with stressful life events, and is typically characterized as problem-focused (i.e., strategies addressing the cause of stress), emotion-focused (i.e., strategies aimed at reducing emotional toll) or avoidant (i.e., strategies that help escape the cause of stress) [11, 12]. Individuals may have a dominant coping style reflected in the most prominent strategies that they use, but they may also invoke other styles and strategies depending on the situation causing the stress [13]. Previous research suggests that a number of factors are related to coping styles. For example, accumulation of stressful life events during a specific time period is associated with higher stress levels, lower levels of problem-focused coping and higher levels of both avoidant [14] and emotion-focused coping [15]. Further, coping styles are associated with several outcomes such as resilience, substance use, anxiety and depression [16,17,18].

There is evidence that problem-focused coping is inversely associated, and avoidant coping is positively associated with depressive symptoms [5, 18]. In contrast, emotion-focused coping has been associated with depressive symptoms both positively [18] and negatively [19]. Differences in the direction of this association may relate to the specific valence of emotion tapped in different measures of coping style. For example, negative emotion-focused coping strategies such as rumination (i.e., repetitive thoughts of one’s feelings about the situation) and self-blame [18, 20]. increase depressive symptoms, whereas positive emotion-focused coping strategies such as acceptance and emotional support decrease depressive symptoms [19]. Thus, emotion-focused coping is more or less protective depending on whether the measure reflects distress or self-deprecation or acceptance and emotional support [21, 22].

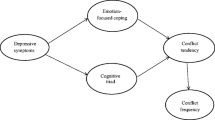

Although stressful life events, coping styles and depressive symptoms are associated, the mechanisms underpinning how they inter-relate are less understood. If stressful life events influence coping styles (i.e., aligned with the transactional theory of stress and coping) [11] which then impact depressive symptoms, then coping styles may mediate the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms. Evans et al. [14] found an indirect effect of stressful life events on depressive symptoms through primary control engagement (i.e., a combination of problem-focused and some positive emotion-focused coping strategies) and avoidant coping. Thus, stressful life events were associated with less use of primary control engagement and greater use of avoidant coping, which contributed to depressive symptoms [14]. Other authors [5] reported no mediation such that stressful life events did not predict coping styles even though both stressful life events and avoidant coping predicted depressive symptoms.

In addition to the potential role of coping style as a mediator, the magnitude of the stressful life events and depressive symptoms association may differ by level of coping style. For example, one study reported no significant moderation by problem-focused coping strategies [23], but another suggests that emotion-focused coping is a moderator [24]. Scott et al. [24] found that the relationship between stressful life events and depressive symptoms was stronger among individuals with high levels of emotion-focused coping.

Because moderation by coping style may be present and because it is possible that coping style is both a mediator and a moderator [25, 26], investigating moderation and mediation concurrently could elucidate these underlying mechanisms. More specifically, by disentangling the role of mediation and moderation, we can improve our understanding of the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms and thus better assess what might occur when we intervene on coping styles.

The objectives in this study were to examine each of problem, emotion, and avoidance-focused coping style as a potential mediator and/or moderator of the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms using the four-way decomposition method. This method permits decomposition of the total effect into portions attributable to each of mediation and moderation, including moderation only, mediation only, mediated interaction and neither mediation nor moderation.

Methods

Data were drawn from the Nicotine Dependence in Teens (NDIT) Study, an ongoing longitudinal study in which 1294 participants were recruited in 1999–2000 from 10 high schools in Montreal, Canada. Schools were purposively selected to include both English and French students, student populations in urban, suburban and rural areas and students living in low, moderate and high socio-economic status neighborhoods [27]. The study received ethics approval from the Montreal Department of Public Health Ethics Review Committee, the McGill University Faculty of Medicine Institutional Review Board, the Ethics Research Committee of the Centre de Recherche du Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and the University of Toronto.

The current analysis draws data from self-report questionnaires collected post-high school (i.e., in cycle 22 conducted in 2011–12) when participants were age 24 years on average. Cycle 22 included 858 participants. Data for all covariates were drawn from cycle 21, which was conducted in 2007–8 when participants were age 20 years on average. Our analyses were restricted to participants with complete data on the main study variables and covariates (n = 782).

Study variables

Depressive symptoms

Data on depressive symptoms were collected using the Major Depression Inventory (MDI), a 10-item self-report scale based on DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria for depression [28]. Participants reported the frequency of experiencing symptoms in the last two weeks on a six-point scale ranging from “at no time” to “all the time” scored 0 to 5. Items 8 and 10 each have two sub-items a and b—only the highest score of a or b was retained for scoring (Table A1). The total score ranged from 0 to 50 points, with higher scores indicating a higher frequency of depressive symptoms. The MDI scale has been validated and is reliable in adults [29]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency of the MDI scale in the current study was 0.89.

Stressful life events

Data on stressful life events in the past year were obtained using questionnaire items adapted from the List of Threatening Experiences and from the Long-term Difficulties Inventory [30, 31]. Participants were asked: “Did you experience any of the following in the past 12 months?”. Twenty-three events/circumstances were listed in the questionnaire and participants were given the option to specify any other life event not included in the list. As is often done in research using stressful life events checklists [18, 32], a cumulative stressful life events (i.e., representing events that occurred in the past year) score was created by summing all events (range 0 – 23).

Coping style

The short-form of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations was used to measure coping style, which includes 21 items and assesses problem-focused (7 items; e.g. focus on the problem and see how I can solve it), emotion-focused (7 items; e.g. blame myself for not knowing what to do) and avoidant (7 items; e.g. take time off and get away from the situation) coping [12, 33]. Coping style was assessed using the following question: “People react to difficult, stressful, or upsetting situations in different ways. How often do you do each of the following when you experience such a situation?” Participants responded on a five-point scale from “never” to “very often” scored from 1 to 5 and scores were averaged for each coping style. In NDIT, the internal consistency of each coping subscale was good (i.e., problem-focused coping: α = 0.88, emotion-focused coping: α = 0.86, avoidant coping: α = 0.78).

Covariates

Age, sex, participant education and earlier depressive symptoms (i.e., measured 3–4 years prior to cycle 22 in cycle 21) were potential confounders of the associations among stressful life events, coping style and depressive symptoms [15, 34, 35]. Participant education was coded attended/graduated high school, attended/graduated CEGEP (i.e., Collège d'enseignement général et professionnel) or attended/graduated university. CEGEPs are post-secondary educational institutions in Quebec that offer programs preparing students for university or for employment. Education was used as a proxy for socio-economic status because it is associated with future employment and income [36]. Earlier depressive symptoms were measured using the MDI scale.

Data analysis

To describe differences between participants retained and not retained for analysis, mean and proportions were reported. To examine mediation and moderation of each coping style, we used VanderWeele’s four-way decomposition approach [26] which decomposes the total effect (TE) of stressful life events on depressive symptoms into four components: controlled direct effect (CDE), reference interaction (INTref), mediated interaction (INTmed) and pure indirect effect (PIE). CDE is the effect of stressful life events on depressive symptoms that is not due to either mediation or moderation by coping style. In other words, it reflects the effect of the exposure on the outcome through pathways that do not require the mediator of interest. INTref is the effect due to moderation only (i.e., the effect of stressful life events on depressive symptoms that operates in presence of coping style, if stressful life events are not necessary for using a coping style). INTmed is the effect due to both mediation and moderation (i.e., the effect of stressful life events on depressive symptoms that operates in the presence of coping style if stressful life events are necessary for adopting a coping style). PIE is the effect due to mediation only (i.e., the effect of coping style on depressive symptoms if stressful life events are necessary for using a coping style).

Three models were constructed, one for each coping style as a potential mediator/moderator, with stressful life events as the exposure and depressive symptoms as the outcome (all of which were entered into the models as continuous variables).

Since the mediation hypothesis assumes that the exposure occurs before the mediator and that both occur before the outcome, the temporality of the reference periods for these variables is important. Although data on stressful life events, coping style and depressive symptoms were collected in the same data collection cycle, the reference period was “past year” for stressful life events and “past two weeks” for depressive symptoms (Fig. 1). The potential mediator (i.e., coping style) was measured as a general response to stressful life events with no specific time frame (i.e., the question asked participants to report their coping style when facing a stressful situation). However, based on transactional theory of stress and coping [11] which posits that coping styles are a stress response, and because several studies concur that stressful life events predict coping style [14, 15], we assumed herein that stressful life events occurred before coping style.

Sensitivity analyses

Given that the variables of interest were continuous, we verified that the assumption of linearity held in the associations among stressful life events, coping styles and depressive symptoms (Tables A3-A4). Since chronic depressive symptoms may influence the results, each mediation model was adjusted for history of a depression diagnosis measured in cycle 21 in addition to age, sex, education and earlier depressive symptoms. History of a depression diagnosis was measured by “Has a health professional ever diagnosed you with a mood disorder?”. Also, given that the association among stressful life events, coping styles and depressive symptoms could differ by sex, we conducted separate mediation models for males and females for each coping style adjusting for age, education and earlier depressive symptoms.

Analyses were conducted using R software version 3.6.1 [RStudio version 1.2.5019]. Confidence intervals were computed using bootstrap resampling.

Results

Table 1 compares selected characteristics of participants retained (n = 782) and not retained (n = 512) for analysis. Among participants excluded, 436 did not participate in the data collection in 2011–12 (cycle 22), 66 were missing data on covariates and 10 were missing data on the exposure, mediator or outcome (Table A2). Compared to those not retained, participants in the analytical sample were younger on average, higher proportions were female, born in Canada, had university-educated mothers and had attended/graduated from CEGEP or university. There were no substantive differences between participants retained and not retained in language, number of stressful life events, coping style or depressive symptoms.

Table 2 presents the four-way decomposition of the TE between stressful life events and depressive symptoms for each coping style. In all three coping style models, stressful life events were positively associated with depressive symptoms, as reflected by the TE.

In the problem-focused coping model, INTmed and PIE were zero with narrow confidence intervals, indicating that problem-focused coping did not mediate the stressful life events and depressive symptoms association. The only estimates for which the confidence intervals excluded the null were for CDE (\(\widehat{\beta }\)(95% CI) = 2.26(1.16, 3.24)) and INTref (\(\widehat{\beta }\)(95% CI) = -1.51(-2.40, -0.53)). CDE implies that there is a positive association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms in the absence of problem-focused coping. The INTref estimate indicates that a portion of the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms is due to moderation, and that the interaction between stressful life events and problem-focused coping decreases reporting of depressive symptoms. More specifically, the association between stressful life events and depression was weaker among participants who used problem-focused coping relative to the association among participants who did not use it, suggestive that problem-focused coping mitigates the effect of stressful life events on depressive symptoms.

In the emotion-focused coping model, all four decomposition components were non-zero with precise confidence intervals suggesting that mediation and moderation were present. These results indicate that a portion of TE is explained by CDE (\(\widehat{\beta }\)(95% CI) = -0.83(-1.38, -0.26)) which suggests that in the absence of emotion-focused coping, stressful life events are negatively associated with depressive symptoms. Second, a greater portion of TE is explained by moderation only (\(\widehat{\beta }\)(95% CI) = 1.16(0.57, 1.69)) which indicates that the interaction between stressful life events and emotion-focused coping increases the self-report scores for depressive symptoms. Also, the confidence intervals for the INTmed (\(\widehat{\beta }\)(95% CI) = 0.03(0.01, 0.05)) and PIE (\(\widehat{\beta }\)(95% CI) = 0.15(0.04, 0.24)) estimates excluded the null suggesting that emotion-focused coping mediated some of the effect. This suggests that individuals experiencing more stressful life events also report greater use of emotion-focused coping and higher scores on depressive symptoms. However, INTmed and PIE estimates were smaller compared to INTref indicating that a greater proportion of the total effect is explained by moderation by emotion-focused coping than mediation.

Finally, in the avoidant coping model, the confidence intervals of all four components of the TE included the null suggesting that avoidant coping did not mediate or moderate the stressful life events and depressive symptoms association.

The results of the sensitivity analyses adjusting for a depression diagnosis in addition to the other covariates included in the main analyses (Table A5) are similar to those reported in the main analyses. Although precision was limited by smaller sample sizes, analyses stratified by sex indicated that the findings are similar across sex (Tables A6 and A7).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study using the four-way decomposition approach to disentangle the mediating and/or moderating role of coping style in the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms in young adults. As expected [5, 6], stressful life events were associated with depressive symptoms, adding evidence to the extant literature that this association is robust in young adults. Three key findings emerged from the four-way decomposition analyses.

First, problem-focused coping did not mediate, but it did moderate the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms. Consistent with Dyson and Renk [5], problem-focused coping was not affected by stressful life events. However, the relationship between stressful life events and depressive symptoms was weaker for individuals using problem-focused coping. As suggested in previous studies [5, 19], problem-focused coping may protect against depressive symptoms. Specifically, problem-focused coping is adaptive since it helps individuals face the stressor and manage it directly, which reduces overall stress. However contrary to our findings, Lewis et al. [23] found no moderation by problem-focused coping strategies, possibly because their study included high-risk HIV-positive adolescents who may cope differently than healthy adolescents. Our findings also differed from Evans et al. [14] who reported that problem-focused coping strategies mediated the association. Their findings suggested that experiencing more stressful life events among youth is associated with lower levels of problem-focused coping (i.e., coping impairment) which in turn is associated with more depressive symptoms. However, measurement of problem-focused coping differed across studies (i.e., Evans et al. combined problem-focused coping with several positive emotion-focused coping strategies), which could partially account for differences in the findings across studies.

Second, emotion-focused coping mediated and moderated the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms. The presence of mediation indicates that the use of emotion-focused coping partially explains the stressful life events and depressive symptoms association. This aligns with the transactional theory of stress and coping [11]. Following a stressful experience, individuals assess whether they can deal with the situation and what they can do about it, leading to the adoption of a coping style. Although Dyson and Renk [5] found no association between stressful life events and emotion-focused coping in college students, their emotion-focused coping measure included mostly positive strategies (i.e., acceptance, emotional support) whereas our measure included negative strategies only (i.e., self-blame, focusing on one’s general inadequacies). Thus, stressful life events seem to be associated with negative emotion-focused coping which is consistent with Undheim and Sund [15], who showed that individuals exposed to more stressful life events tend to use maladaptive coping styles. Since life events occur at specific moments in time, but can induce a state of stress over a longer period because of higher demands of the situation [37], we suggest that an increase in number of stressful life events is associated with coping impairment. For example, more stressful life events may induce stress which increases use of negative emotion-focused coping and depressive symptoms and in turn leads to a repeated cycle of stress and negative emotion coping. In addition to mediation, a substantial portion of the association was explained by moderation. As reported elsewhere [24], individuals who use more emotion-focused coping in stressful situations experience more depressive symptoms. Thus, moderation by emotion-focused coping suggests that there is a stronger association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms among individuals who tend to use emotion-focused coping.

Lastly, although previous findings report associations between avoidant coping and both stressful life events and depressive symptoms [5, 15, 38], we found no evidence of mediation or moderation by avoidant coping. This is contrary to Evans et al. [14] who found that behavioral (i.e., quit trying; reducing efforts to reach goal) or mental (i.e., sleep; watch TV; denial) disengagement mediated the association. While our avoidant coping measure also included strategies to avoid thinking about the stressor, some items in our scale reflected social activities or interaction (i.e., going out for a meal; calling or visiting a friend) which could be adaptive and help in the short-term. Overall, differences in avoidant coping measures may explain the mixed findings, and not dealing with the stressor(s) directly may be associated with long-term consequences.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include use of an analytical approach which allowed simultaneous assessment of mediation and moderation compared to some traditional mediation methods. Data on stressful life events, coping style and depressive symptoms were collected in the same cycle. However, the reference time frame for the exposure (i.e., “past year” life events) and outcome (i.e., depressive symptoms in the “past two weeks) overlapped by two weeks. Although it is likely that life events preceded depressive symptoms, it is also possible that: (i) past two-week depressive symptoms reflected long-term chronic depression; and (ii) life events could have occurred during the same two-week period referred to in the depressive symptoms reference period). We could not establish temporality between stressful life events and coping style because the coping style question did not refer to a specific time frame. Rather, drawing from the transactional theory of stress and coping [11] and two studies showing that life events predicted coping styles [14, 15], we assumed that exposure preceded coping style, which is key for causal mediation analysis. Future studies should use longitudinal designs in which the temporality across study variables is clearly delimited to examine whether coping styles mediate and/or moderate the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms in young adults. The causal interpretations of mediation analysis rely on the assumptions of no unmeasured confounding of the associations among exposure, mediator and outcome [39]. Although we controlled for potential confounders, residual confounding may be present due to unmeasured confounders such as self-esteem, social support and childhood adversity. Limitations also include that selection bias due to loss to follow-up may have affected the estimates and that purposive sampling of schools at NDIT inception could limit generalizability. Self-report measures of stressful life events using checklists are subject to misclassification (i.e., long recall periods can lead to underreporting of stressful life events) which can lead to information bias. Also, as a measure, our cumulative stressful life event scores does not reflect the chronicity of each stressor (i.e., whether the stressor was acute or chronic). It does not distinguish whether one event was more stressful than another, and it does not reflect the timing of the stressful events with respect to each other, all of which could affect the results. If our temporality assumption does not hold, the models cannot be interpreted causally and would merely reflect correlations between the variables. Although the number of events predicts health outcomes [40], future studies should consider investigating these mechanisms using interview-based stressful life event measures to improve understanding of the type, severity and participant reaction to events contributing to these associations. Also, non-linear associations should be further examined in studies with larger sample sizes. Lastly, our study was underpowered to examine the role of gender which could have important implications in the association among stressful life events, coping styles and depressive symptoms. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to identify the role of gender in these associations.

Conclusion

This study clarifies the role of different coping styles (i.e., problem-focused, emotion-focused, avoidant) in the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms among young adults. We found mediation only through emotion-focused coping, and moderation by both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping. These results suggest that young adults exposed to more stressful life events are more likely to experience depressive symptoms which could be explained by higher emotion-focused coping. In the event where individuals are exposed to the same number of stressful life events, those using problem-focused coping will experience fewer depressive symptoms compared to those not adopting this coping style, while those using emotion-focused coping will experience more depressive symptoms. Based on these findings, preventive interventions for depressive symptoms in young adults should focus on reinforcing problem-focused coping strategies and discouraging use of negative emotion-focused coping strategies in dealing with stressful life events.

Data availability

NDIT data are available on request. Access to NDIT data is open to any university-appointed or affiliated investigator upon successful completion of the application process. Masters, doctoral and postdoctoral students may apply through their primary supervisor. To gain access, applicants must complete a data access form available on our NDIT website (www.CELPHIE.ca) and return it to the principal investigator (jennifer.oloughlin@umontreal.ca).

References

American College Health Association (2019) American college health association-national college health assessment II: Canadian consortium executive summary. Silver Spring, MD

Hysenbegasi A, Hass S, Rowland C (2005) The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. J Ment Health Policy Econ 8(3):145–151

Alonso J, Mortier P, Auerbach RP, Bruffaerts R, Vilagut G, Cuijpers P, Demyttenaere K, Ebert DD, Ennis E, Gutierrez-Garcia RA, Green JG, Hasking P, Lochner C, Nock MK, Pinder-Amaker S, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC, Collaborators WW-I (2018) Severe role impairment associated with mental disorders: results of the WHO world mental health surveys international college student project. Depress Anxiety 35(9):802–814. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22778

Lepine JP, Briley M (2011) The increasing burden of depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 7(Suppl 1):3–7. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S19617

Dyson R, Renk K (2006) Freshmen adaptation to university life: depressive symptoms, stress, and coping. J Clin Psychol 62(10):1231–1244. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20295

Suzuki M, Furihata R, Konno C, Kaneita Y, Ohida T, Uchiyama M (2018) Stressful events and coping strategies associated with symptoms of depression: a Japanese general population survey. J Affect Disord 238:482–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.024

Friis RH, Wittchen HU, Pfister H, Lieb R (2002) Life events and changes in the course of depression in young adults. Eur Psychiatry 17:241–253

Hazel NA, Oppenheimer CW, Technow JR, Young JF, Hankin BL (2014) Parent relationship quality buffers against the effect of peer stressors on depressive symptoms from middle childhood to adolescence. Dev Psychol 50(8):2115–2123. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037192

Arnett J (2000) Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol 55(5):469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469

Brown LH, Strauman T, Barrantes-Vidal N, Silvia PJ, Kwapil TR (2011) An experience-sampling study of depressive symptoms and their social context. J Nerv Ment Dis 199(6):403–409. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31821cd24b

Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Dunkel-Schetter C, DeLongis A, Gruen RJ (1986) Dynamics of a stressful encounter : cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. J Pers Soc Psychol 50(5):992–1003. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992

Endler NS, Parker JDA (1994) Assessment of multidimensional coping: task, emotion, and avoidance strategies. Psychol Assess 6(1):50–60. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.1.50

Jackson Y, Huffhines L, Stone KJ, Fleming K, Gabrielli J (2017) Coping styles in youth exposed to maltreatment: longitudinal patterns reported by youth in foster care. Child Abuse Negl 70:65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.05.001

Evans LD, Kouros C, Frankel SA, McCauley E, Diamond GS, Schloredt KA, Garber J (2015) Longitudinal relations between stress and depressive symptoms in youth: coping as a mediator. J Abnorm Child Psychol 43(2):355–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9906-5

Undheim AM, Sund AM (2017) Associations of stressful life events with coping strategies of 12–15-year-old Norwegian adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 26(8):993–1003. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-0979-x

Campbell-Sills L, Cohan SL, Stein MB (2006) Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behav Res Ther 44(4):585–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001

Garnefski N, Legerstee J, Kraaij V, Van Den Kommer T, Teerds JAN (2002) Cognitive coping strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety: a comparison between adolescents and adults. J Adolesc 25(6):603–611. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2002.0507

Rafnsson FD, Jonsson FH, Windle M (2006) Coping strategies, stressful life events, problem behaviors, and depressed affect. Anxiety Stress Coping 19(3):241–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800600679111

Morris MC, Evans LD, Rao U, Garber J (2015) Executive function moderates the relation between coping and depressive symptoms. Anxiety Stress Coping 28(1):31–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2014.925545

Michl LC, McLaughlin KA, Shepherd K, Nolen-Hoeksema S (2013) Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults. J Abnorm Psychol 122(2):339–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031994

Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Cameron CL, Ellis AP (1994) Coping through emotional approach: problems of conceptualization and confounding. J Pers Soc Psychol 66(2):350–362. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.66.2.350

Stanton AL, Low CA (2012) Expressing emotions in stressful contexts: benefits, moderators, and mechanisms. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 21(2):124–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411434978

Lewis JV, Abramowitz S, Koenig LJ, Chandwani S, Orban L (2015) Negative life events and depression in adolescents with HIV: a stress and coping analysis. AIDS Care 27(10):1265–1274. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2015.1050984

Scott RM, Hides L, Allen JS, Lubman DI (2013) Coping style and ecstasy use motives as predictors of current mood symptoms in ecstasy users. Addict Behav 38(10):2465–2472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.05.005

MacKinnon DP, Valente MJ, Gonzalez O (2020) The correspondence between causal and traditional mediation analysis: the link Is the mediator by treatment interaction. Prev Sci 21(2):147–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-019-01076-4

VanderWeele TJ (2014) A unification of mediation and interaction: a 4-way decomposition. Epidemiology 25(5):749–761. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000121

O’Loughlin J, Dugas EN, Brunet J, DiFranza J, Engert JC, Gervais A, Gray-Donald K, Karp I, Low NC, Sabiston C, Sylvestre MP, Tyndale RF, Auger N, Auger N, Mathieu B, Tracie B, Chaiton M, Chenoweth MJ, Constantin E, Contreras G, Kakinami L, Labbe A, Maximova K, McMillan E, O’Loughlin EK, Pabayo R, Roy-Gagnon MH, Tremblay M, Wellman RJ, Hulst A, Paradis G (2015) Cohort profile: the nicotine dependence in teens (NDIT) study. Int J Epidemiol 44(5):1537–1546. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu135

Bech P, Timmerby N, Martiny K, Lunde M, Soendergaard S (2015) Psychometric evaluation of the major depression inventory (MDI) as depression severity scale using the LEAD (longitudinal expert assessment of all data) as index of validity. BMC Psychiatry 15:190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0529-3

Bech P, Rasmussen N, Raabaek Olsen L, Noerholm V, Abildgaard W (2001) The sensitivity and specificity of the major depression inventory, using the present state examination as the index of diagnostic validity. J Affect Disord 66(2–3):159–164

Brugha T, Cragg D (1990) The list of threatening experiences: the reliability and validity of a brief life events questionnaire. Acta Psychiatr Scand 82(1):77–81

Rosmalen JG, Bos EH, de Jonge P (2012) Validation of the long-term difficulties inventory (LDI) and the list of threatening experiences (LTE) as measures of stress in epidemiological population-based cohort studies. Psychol Med 42(12):2599–2608. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712000608

Manczak EM, Skerrett KA, Gabriel LB, Ryan KA, Langenecker SA (2018) Family support: a possible buffer against disruptive events for individuals with and without remitted depression. J Fam Psychol 32(7):926–935. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000451

Endler NS, Parker JDA (1990) Coping inventory for stressful situations (CISS): manual. Multi-Health Systems, Toronto

Johnson DP, Whisman MA, Corley RP, Hewitt JK, Rhee SH (2012) Association between depressive symptoms and negative dependent life events from late childhood to adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 40(8):1385–1400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9642-7

Brougham RR, Zail CM, Mendoza CM, Miller JR (2009) Stress, sex differences, and coping strategies among college students. Curr Psychol 28(2):85–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-009-9047-0

Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey Smith G (2006) Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health 60(1):7–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.023531

Epel ES, Crosswell AD, Mayer SE, Prather AA, Slavich GM, Puterman E, Mendes WB (2018) More than a feeling: a unified view of stress measurement for population science. Front Neuroendocrinol 49:146–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.03.001

Seiffge-Krenke I, Klessinger N (2000) Long-term effects of avoidant coping on adolescents’ depressive symptoms. J Youth Adolesc 29(6):617–630

VanderWeele TJ, Vansteelandt S (2009) Conceptual issues concerning mediation, interventions and composition. Stat Interface 2:457–468

Cohen S, Murphy MLM, Prather AA (2019) Ten surprising facts about stressful life events and disease risk. Annu Rev Psychol 70:577–597. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-

Acknowledgements

MPS holds a Junior 2 Salary Award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS). ID holds a Junior 1 Award from FRQS. JOL held a Canada Research Chair in the Early Determinants of Adult Chronic Disease 2004-2021. CMS holds a Canada Research Chair (CRC) in Physical Activity and Mental Health. The authors thank the NDIT participants, their parents, and the schools that participated in NDIT.

Funding

The NDIT (Nicotine Dependence in Teens) study was supported by the Canadian Cancer Society (grants 010271, 017435, 704031).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AP completed the literature review, conducted the analyses and wrote the manuscript. JOL and ID supervised this research project, participated in decisions related to the analyses and critically reviewed the manuscript. MPS and CMS critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have indicated that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethics approval for the NDIT study was granted by the Montreal Department of Public Health Ethics Review Committee, the McGill University Faculty of Medicine Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Research Committee of the Centre de Recherche du Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and the University of Toronto.

Consent to participate

Parents/guardians provided written consent at inception. Participants provided consent post-high school.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pelekanakis, A., Doré, I., Sylvestre, MP. et al. Mediation by coping style in the association between stressful life events and depressive symptoms in young adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 57, 2401–2409 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02341-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02341-8