Abstract

The Stress Generation Hypothesis (SGH) suggests that depressive symptoms lead to stressful interpersonal life events. Based on this hypothesis, a theoretical model was proposed, which tested whether depressive symptoms predict interpersonal conflict via the cognitive triad, emotion-focused coping, and conflict tendency. A non-clinical sample of undergraduate university students (N = 313) participated in the present study. Most participants were female (251 women, 62 men). The mean age of the sample was 20.27 (SD = 3.75). Participants completed a questionnaire set composed of the Beck Depression Inventory, Cognitive Triad Inventory, The Ways of Coping Scale, Conflict Tendency Scale, and Form of Conflict in Close Relationships. According to the model, depressive symptoms were significantly associated with emotion-focused coping and negative cognitive triad, both of which were related with conflict tendency that was in turn associated with conflict frequency. The model explained 24% of the variance in conflict frequency. In future studies and psychotherapy practice, depressive symptoms, emotion-focused coping, and negative attributions about the self, others, and the future should be taken into account with regard to interpersonal conflict.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Stress Generation Hypothesis

Early studies that focused on the effect of stress as a vulnerability factor for depression provided the evidence for the stress-diathesis model (Hammen 2005; Morris et al. 2008). According to the stress-diathesis model, stressful life events result in depression by interacting with diathesis factors (Abramson et al. 1989; Brown and Harris 1978; Hammen 2005). On the other hand, contemporary studies have brought a different perspective, showing that stress might be both a predictor and an outcome of depression. In the literature, this process has been explained by the Stress Generation Hypothesis (SGH; Hammen 1991, 2006).

The SGH postulates that individuals are not passive recipients of stressful life events around them. Rather, individuals have an effect on these events; that is, they change their surroundings. In terms of this hypothesis, individuals generate stressful life events in interpersonal contexts due to their depressive symptoms. In addition, some interpersonal relationship patterns such as attachment and cognitive styles increase the risk of experiencing stressful life events (Hammen 1991, 2005; Liu 2013). In summary, the SGH asserts that individuals generate negative interpersonal life events because of their depressive symptoms or some other individualistic features. As a process, stressful life events increase depressive symptoms, while depressive symptoms increment the risk of experiencing interpersonal stressful life events, which further increase depressive symptoms (Liu and Alloy 2010; Liu 2013).

The relevant literature divides negative life events into two types: dependent and independent life events (Liu 2013; Miller et al. 1986). Dependent life events are at least partly influenced by an individual’s psychological features. The individual has an active role on experiencing these kind of events (e.g., an argument in a romantic relationship). However, independent life events are uncontrollable (e.g., a natural disaster). According to the SGH, depressive symptoms or interpersonal relationship styles increase the possibility of experiencing dependent negative life events while independent negative life events are not affected by these variables (Liu 2013; Liu and Alloy 2010). Empirical studies using different methods have indicated that depressive symptoms predict dependent negative life events (Calvete et al. 2013; Flynn and Rudolph 2011; Kleiman et al. 2015; Krackow and Rudolph 2008; Liu 2013).

Dependent Life Stress: Conflicts in Relationships

Conflict includes misunderstandings, disagreements, disparagement, disapproval, criticism, sarcasm, or rejection in the communication process. When a conflict occurs in an interpersonal relationship, communication lacks warmth, nurturance, care, and empathy (Major et al. 1997). Conflict in communication generally stems from different thoughts, values, and feelings between individuals (Rahim et al. 2000). In the process of conflict, some individuals cannot use confrontation, self-disclosure, or emotional expression to deal with it (Goldstein 1999) since they may lack of emotional well-being and the ability to interpret conflict events in healthy ways (Mayer 2000). As this process suggests, some dysfunctional cognitive processes and ways of coping can make individuals prone to experiencing more conflicts in relationships. Relatedly, conflict tendency has been defined as the potential risk of conflict in an interpersonal context due to dysfunctional communication style. This communication style includes negative thinking and behavior style (Dokmen 1986). At the same time, dysfunctional cognition (Timbremont and Braet 2006) as a negative thinking style and negative ways of coping (Hori et al. 2014) as a dysfunctional behavioral style are common features of depressive symptoms. Therefore, negative cognitive styles and negative ways of coping may be associated with a general conflict tendency in the interpersonal communication process. While past studies have indicated that depressive symptoms predict interpersonal conflict (Eberhart and Hammen 2009; Flynn and Rudolph 2011), conflict tendency has not been examined as an outcome of depressive cognition and ways of coping.

Mediators: Cognitive Vulnerabilities and Coping

Studies focusing on negative dependent life stress have shown that cognitive vulnerability factors have a role on stress generation process. For example, it was found that negative inferential and attribution styles predict later dependent life stress (Abramson et al. 1989; Simons et al. 1993). Similar findings have also indicated that self-criticism (Shahar and Priel 2003), negative interpretation, and rumination (Safford et al. 2007) prospectively predict stress generation. Generally, studies on the SGH have addressed negative inferential styles (Shih et al. 2009) and negative attributions (Simons et al. 1993). Negative cognitive triad may be another cognitive vulnerability factor in that depressive symptoms are related with dependent negative life events. Negative cognitive triad is a vulnerability factor in the development and perseverance of depression (Beck 1983). Beck et al. (1979) suggested that individuals with negative cognitions toward the self, world, and future are at a higher risk of developing depression. According to the cognitive triad model, individuals vulnerable to depression tend to attribute present negativity as persistent (negative future perception), attribute events to personal defects (negative self-perception), and see the world with insurmountable obstacles (negative world perception). In this regard, negative future perception, negative self-perception, and negative world perception constitute the cognitive triad. Individuals’ negative interpretations toward the self, world, and future increase when depressive symptoms increase (Calvete et al. 2013).

Coping styles are cognitive and behavioral strategies used repeatedly in similar stressful situations (Compas 1987). Problem- and emotion-focused coping are two main approaches to coping styles (Endler and Parker 1990). Individuals employing problem-focused coping approach problems in a logical, active, and conscious way, while individuals who employ emotion-focused coping avoid, occupy, or comply with emotions (Folkman et al. 1986). Whether a coping style is adaptive or maladaptive depends on the situation (Folkman and Lazarus 1980). If the situation is uncontrollable and unchangeable like independent life events, emotion-focused coping can be adaptive. On the contrary, when the situation is controllable like dependent interpersonal conflicts and the individual uses emotion-focused coping, this strategy becomes maladaptive. Coping with interpersonal conflicts requires identifying the problem and finding alternative solutions. Individuals using emotion-focused coping focus on their emotions instead of conflict resolution. Some related studies within the SGH framework have shown that avoidance coping, poor interpersonal problem solving predict stress generation (Davila et al. 1995; Holahan et al. 2005; Nezu and Carnevale 1987).

It is not possible to understand interpersonal negative life events only by depressive symptoms. It is important to examine how depressive symptoms affect interpersonal negative life events through cognitive and behavioral mediator mechanisms. Studies have investigated the role of some cognitive variables and coping on stress generation (Carter and Garber 2011; Holahan et al. 2005; Liu 2013), but cognitive factors and ways of coping were not used as mediators to discern the role of depressive symptoms on the stress generation process in these studies.

Summary and Aim of the Study

Many studies have suggested the importance of depressive symptoms on the stress generation process. Additionally, cognitive styles and ways of coping play a role on this process. However, it is not yet known exactly how depressive symptoms lead to stress generation. In this study, a mediation model was proposed and tested to present an explanation of how depressive symptoms lead to stress generation. Further, empirical work in this area has not yet tested mediator roles of both cognitive styles, ways of coping, and conflict tendency together to determine the association between depressive symptoms and conflict generation in interpersonal relationships.

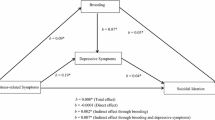

Based on the prior studies and theoretical considerations mentioned above, it was hypothesized that people with non-clinical depressive symptoms would have more negative perceptions toward the self, future, and world (negative cognitive triad), and they would use more emotion-focused coping, all of which would result in conflict tendency. This conflict tendency would also be related to increase in interpersonal conflict frequency. This process was shown in the proposed model (see Fig. 1).

Methods

Participants

A non-clinical sample of undergraduate university students (N = 313) participated in the present study. The majority of participants were female (251 women, 62 men). The mean age of sample was 20.27 years (SD = 3.75), and the participants (86.5%) were mainly from middle-class families. Generally, they (66.9%) were staying in university dorms. Volunteers were given 1 bonus point as compensation by the course instructor.

Instruments

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck 1961) is a 21-item scale that measures cognitive, emotional, somatic, and motivational symptoms of depression in adults. All items are scored between 0 and 3. The highest cumulative score that can be taken from the scale is 63. Higher scores reflect greater level and severity of depressive symptoms. Two independent Turkish adaptation studies were done (Tegin 1980; Hisli 1988, 1989). Studies showed that Turkish form of the BDI was valid and reliable. Test-retest reliability was .65 for students and .73 for patients (Tegin 1980).

Cognitive Triad Inventory (CTI; Beckham et al. 1986) consists of 36 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale. CTI was developed to measure positive and negative cognitions about one’s view of the self (“I can do a lot of things well”), world (“The world is a very hostile place”), and future (“There is no reason for me to be hopeful about my future”). Before calculating the scores, positive cognitions are reverse-scored. Higher scores represent negative cognitions and low scores represent positive cognitions. CTI was adapted into Turkish by Erarslan (2014). The inventory had good reliability and validity. Internal consistency values for view of the self, world, and future subscales were .85, .72, and .87, respectively. Internal consistency of the total scale was .91.

The Ways of Coping Scale (WOCS; Folkman and Lazarus 1988) is a 66-item questionnaire developed to investigate thoughts and acts that people use to deal with stressful encounters. Şahin and Durak (1995) adapted the scale into Turkish. By investigating item-total correlations and internal consistencies of the total scale and subscales, the scale was converted into a 30-item short-form version. This new form consists of five subscales: self-confident approach, optimistic approach, seeking social support (effective ways of coping), and helpless style and submissive style (ineffective/emotion focused coping). Internal consistencies of the subscales were .83, .79, .63, .73, and .65, respectively. When categorizing ways of coping as effective and ineffective, internal consistencies were found to be .83 for effective and .78 for ineffective ways of coping.

Conflict Tendency Scale (CTS; Dokmen 1986) consists of 53 items and is scored on 5-point Likert scale. It has 10 subscales: Active conflict, passive conflict, existence conflict, completely rejection conflict, biased conflict, intensity conflict, active-biased conflict, passive completely rejection conflict, humane features, and personality traits. Total scores change between 53 and 265. Low scores indicate low conflict tendency, and high scores indicate high conflict tendency. Internal consistency of the CTS was .77 and test-retest reliability was .89 in the original study (Dokmen 1986). Therefore, CTS was reliable and valid measure.

Form of Conflict in Close Relationship (FCCR) aims to investigate participants’ perceived derangement, conflicts, discussions, confrontations, and fights in five close relationship categories (mother, father, sibling, romantic partner, and social friend) within last 6 months (mother, father, sibling, romantic partner, and social friend). People maintain close relationships with their mother, father, siblings, friends, and romantic partner, and conflict occurs mostly in these relationships (Brehm et al. 2002). For that reason, the FCCR was developed by authors via reviewing measurements of interpersonal stress events. Participants were asked to rate the frequency of conflict for each of the five categories on a 5-point Likert scale. Preliminary reliability and validity analyses were conducted. Cronbach’s alpha for the total form was .54. The total scores of the FCCR were significantly correlated with CTS and BDI, .37 and .26, respectively. The results of the analyses demonstrated the suitability of FCCR for use in this study.

Procedure and Data Analysis

Before running the study, ethical approval was obtained from Hacettepe University Ethical Committee. Participants were recruited from the Hacettepe University Psychology Department and other departments convenient to reach. Informed consents were distributed, participants signed them, and then they were collected back. After that, volunteer participants were asked to complete the scales. This process took about 40 min.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the model by using AMOS version 16. The ratio of χ2/degrees of freedom (df), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used to determine the model’s fit to the data. Furthermore, preliminary analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20. Missing values were assigned with the series by mean method. Univariate outlier analysis was done to find deviant cases. No outliers were detected in the data according to the statistical rule of z-scores of ±4.00 for univariate outliers in samples larger than 100 participants (Mertler and Vannatta 2005). After that, other assumptions (such as normality) were checked in terms of criteria stated by Field (2009). Skewness and kurtosis values of continuous variables were in normal range (lower than ±1).

Testing a model using SEM first required determining the observed variables of latent constructs. The observed variables of negative cognitive triad and emotion-focused coping latents were represented by the subscale dimensions while observed variables of depressive symptoms and conflict tendency were determined by the parcel method. On the other hand, conflict frequency latent was represented by five self-rated single-item questions, each asking for the frequency of conflict in close relationships (mother, father, sibling, partner, and social friend). Self, world, and future subscales of the CTI represented the cognitive triad latent factor. Two ways of emotion-focused coping (the helpless and submissive styles) comprised the coping latent factor, while the depressive symptoms and conflict tendency latent factors were represented by the parcels. Although there has been debate in the usage of the parcel method in the literature, empirical justifications for parceling have been demonstrated (Bandalos and Finney 2001). Therefore, the parcel method was used as the purpose here was not to examine the relative importance of individual items, but rather, to show whether the theoretically constructed model fits to the data. For example, the CTS (composed of 53 items and 10 subscales) is impractically lengthy for SEM. The BDI shares similar problems with the CTS. Hence, parcels for latent factors of conflict tendency and depressive symptoms were created because of compatibility with the purpose of the present study and practicality (Little et al. 2002).

Parcels were created by the item-to-construct balance method (Little et al. 2002). First, factor analysis was conducted for both the CTS and BDI. Results of factor analysis showed that 16 items in the CTS had factor loadings lower than .30, and item-total correlations were also problematic for the same items. We decided to exclude them and run factor analysis again for the CTS. After this, there were not any items loadings lower than .30. By fixing the factors to 1 in factor analysis, three parcels were created for the CTS by using the item-to-construct method. Regarding the BDI, we did not eliminate any items, as factor loadings were not problematic and created three parcels with the same method.

Results

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

Results of Pearson correlation analysis among unobserved variables included in the structural model are shown in Table 2.

A structural model of stress generation examining the role of depressive symptoms, negative cognitive triad, and emotion-focused coping factors on conflict tendency and conflict frequency was tested (Fig. 2). This model fit to the data well (χ2 = 231.132, χ2/df = 2.335, GFI = .91, CFI = .94, NFI = .90; RMSEA = .06, AIC = 305.132).

Tested model. Note. CT_S = Cognitive Triad Self; CT_W = Cognitive Triad World; CT_F = Cognitive Triad Future; D_ParI = Depression Parcel I; D_ParII = Depression Parcel II; D_ParIII = Depression Parcel III; CT_ParI = Conflict Tendency Parcel I; CT_ParII = Conflict Tendency Parcel II; CT_ParIII = Conflict Tendency Parcel III; CF_M = Conflict Frequency Mother; CF_F = Conflict Frequency Father; CF_S = Conflict Frequency Sibling; CF_P = Conflict Frequency Partner; CF_SF = Conflict Frequency Social Friend. *p < .001

According to the model, depressive symptoms were significantly and positively associated with emotion-focused coping (β = .58, p < .001) and negative cognitive triad (β = .81, p < .001), which were positively related with conflict tendency (β = .30, p < .001 and β = .51, p < .01, respectively), which was in turn positively associated with conflict frequency (β = .49, p < .001). Depressive symptoms explained 50% of the variance in conflict tendency through the roles of emotion-focused coping and negative cognitive triad, while the total model explained 24% of the variance in conflict frequency. Hence, the model indicated that people generate stress or conflict in close relationships not only due to depressive symptoms, but rather, depressive symptoms create conflict in close relationships through the roles of ineffective ways of coping and negative cognitive triad, which constitute conflict tendency.

Discussion

In this study, the proposed and tested model showed that depressive symptoms are associated with interpersonal conflict tendency and frequency through emotion-focused coping styles and negative cognitive triad. Hence, the results indicated that emotion-focused coping and negative cognitive triad, the characteristic features of depressive symptoms, were related to interpersonal conflict tendency, which was associated with conflict frequency. This finding is consistent with both the SGH and related studies showing that depressive symptoms may be an antecedent for dependent life stressors (Calvete et al. 2013; Daley et al. 1998; Hammen 1991, 2006; Kercher and Rapee 2009). Furthermore, this study expanded previous findings of the SGH by testing a mediating mechanism about how depressive symptoms are related with dependent life stressors, especially in the interpersonal domain.

According to the present results, while depressive symptoms increased, negative evaluations about the self, world, and future also increased. This increment led to interpersonal conflict tendency, and conflict tendency also predicted increase in conflict frequency. One of the mediators in this loop was negative cognitive triad. In the stress generation literature, negative inferential styles and negative attributions have predicted later dependent life stressors (Abramson et al. 1989; Safford et al. 2007; Shih et al. 2009). These studies focused on internal, stable, global attributions about negative events and dysfunctional attitudes. However, in the current study, another depression-related structure, negative cognitive triad, was indicated as an important construct in the SGH. For healthy interpersonal communication, individuals should be empathic, open, supportive, and not excessively critical, disapproving, or sarcastic (Major et al. 1997). If an individual interprets the self, world, and future negatively, it may be hard to be empathic, open, and supportive. Such individuals may be more prone to conflict.

Emotion-focused coping (submissive and helpless styles) was another significant mediator in the relationship between depressive symptoms and conflict tendency. The model showed that while depressive symptoms increase, people use more submissive and helpless coping styles, which constitute a potential risk for interpersonal conflicts. This finding implies that individuals with depressive symptoms may not focus on conflict or conflict resolution. Instead, when they encounter a problem in interpersonal domain, they may struggle with their submissive and helpless feelings, which may cause interpersonal communication problems and ultimately conflicts.

This study proposed and tested a model that explains the generation of interpersonal conflicts. Considering the model, depressive symptoms, emotion-focused coping (submissive and helpless), and negative attributions about the self, world, and future should be taken into consideration when studying interpersonal conflict in future empirical research and practice. In psychotherapy practice, depressive symptoms, cognitive factors, and coping strategies should be considered together as sources of interpersonal conflict.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the sample size was sufficient in this study and the model showed acceptable fit, there are some limitations and future directions. The gender effect was not examined due to the small number of male participants. The stress generation process may differ in terms of gender. Thus, this model should be tested in different genders. A non-clinical, university student sample also limits the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should test this model in samples with different age groups and education levels. Furthermore, it is recommended that this model should be confirmed in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) patients. By this way, the model can provide an explanation how patients with MDD become vulnerable to interpersonal conflicts. Consequently, treatment alternatives of MDD can be tailored to specifically addressing interpersonal conflict process since interpersonal conflict process is a dependent negative life event and may further exacerbate depressive symptoms. Additionally, the current study has all the limitations of self-report measures and cross-sectional designs. Beyond this, the conflict frequency measure required participants to report and summarize conflicts during the last 6 months. It might be difficult for the participants to remember the past conflicts. Therefore, future studies should use ecological momentary assessment and/or longitudinal designs.

References

Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96, 358–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.2.358.

Bandalos, D. L., & Finney, S. J. (2001). Item parceling issues in structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides & R. E. Schumacker (Eds.), New development and techniques in structural equation modeling (pp. 269–275). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Beck, A. T. (1961). An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561–571.

Beck, A. T. (1983). Cognitive therapy of depression: New perspectives. In P. J. Clayton & J. E. Barrett (Eds.), Treatment of depression: Old controversies and new approaches (pp. 265–290). New York: Raven Press.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford.

Beckham, E. E., Leber, W. R., Watkins, J. T., Boyer, J. L., & Cook, J. B. (1986). Development of an instrument to measure Beck’s cognitive triad: The cognitive triad inventory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(4), 566–567. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.54.4.566.

Brehm, S. S., Miller, R. S., Perlman, D., & Campbell, S. M. (2002). Intimate relationships. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Brown, G. W., & Harris, T. O. (1978). Social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. New York: Free Press.

Calvete, E., Orue, I., & Hankin, B. L. (2013). Transactional relationships among cognitive vulnerabilities, stressors, and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9691-y.

Carter, J. S., & Garber, J. (2011). Predictors of the first onset of a major depressive episode and changes in depressive symptoms across adolescence: Stress and negative cognitions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(4), 779–796. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025441.

Compas, B. E. (1987). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 101(3), 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.101.3.393.

Daley, S. E., Hammen, C., Davila, J., & Burge, D. (1998). Axis II symptomatology, depression, and life stress during the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 595–603. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.66.4.595.

Davila, J., Hammen, C., Burge, D., Paley, B., & Daley, S. E. (1995). Poor interpersonal problem solving as a mechanism of stress generation in depression among adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 592–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.104.4.592.

Dokmen (1986). The effects of education about facial expressions on the ability to identify emotional facial expressions and tendency to communication conflicts (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey.

Eberhart, N. K., & Hammen, C. L. (2009). Interpersonal predictors of stress generation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(5), 544–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208329857.

Endler, N. S., & Parker, J. D. A. (1990). Multidimensional assessment of coping: A critical evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(5), 844–854. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.844.

Erarslan, O. (2014). The investigation of the mediator role of positive views of self, world and future on the relationship of psychological resilience with depressive symptoms and life satisfaction in university student (Unpublished Master’s thesis). Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS: Sex and drugs and rock’n’roll (3rd ed.). London, UK: Sage Publications.

Flynn, M., & Rudolph, K. D. (2011). Stress generation and adolescent depression: Contribution of interpersonal stress responses. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 1187–1198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9527-1.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 219–239.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(3), 466–475.

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., Delongis, A., & Gruen, R. (1986). The dynamics of a stressful encounter. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 992–1003. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992.

Goldstein, S. B. (1999). Construction and validation of a conflict communication scale. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(9), 1803–1832. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00153.x.

Hammen, C. (1991). Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 555–561. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.555.

Hammen, C. (2005). Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 293–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938.

Hammen, C. (2006). Stress generation in depression: Reflections on origins, research, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 1065–1082. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20293.

Hisli, N. (1988). A study on the validity of Beck depression inventory. Journal of Psychology, 6, 118–126.

Hisli, N. (1989). Beck depression inventory: Reliability and validity for university students sample. Journal of Psychology, 7, 3–13.

Holahan, C. J., Moos, R. H., Holahan, C. K., Brennan, P. L., & Schutte, K. (2005). Stress generation, avoidance coping, and depressive symptoms: A 10-year model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 658–666. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.658.

Hori, H., Teraishi, T., Ota, M., Hattori, K., Matsuo, J., Kinoshita, Y., et al. (2014). Psychological coping in depressed outpatients: Association with cortisol response to the combined dexamethasone/CRH test. Journal of Affective Disorders, 152, 441–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.013.

Kercher, A., & Rapee, R. M. (2009). A test of a cognitive diathesis—Stress generation pathway in early adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 845–855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9315-3.

Kleiman, E. M., Liu, R. T., Riskind, J. H., & Hamilton, J. L. (2015). Depression as a mediator of negative cognitive style and hopelessness in stress generation. British Journal of Psychology, 106, 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12066.

Krackow, E., & Rudolph, K. D. (2008). Life stress and the accuracy of cognitive appraisals in depressed youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(2), 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410801955797.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the questions, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_1.

Liu, R. T. (2013). Stress generation: Future directions and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 406–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.01.005.

Liu, R. T., & Alloy, L. B. (2010). Stress generation in depression: A systematic review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future study. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(5), 582–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.010.

Major, B., Zubek, J. M., Cooper, M. L., Cozzarelli, C., & Richards, C. (1997). Mixed message: Implications of social conflict and social support within close relationships for adjustment to a stressful life event. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(6), 1349–1363.

Mayer, B. (2000). The dynamics of conflict resolution. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mertler, C. A., & Vannatta, R. A. (2005). Advanced and multivariate statistical methods: Practical application and interpretation (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Pyrczak Publishing.

Miller, P. M., Dean, C., Ingham, J. G., & Kreitman, N. B. (1986). The epidemiology of life events and long-term difficulties, with some reflections on the concept of independence. British Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 686–696. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.148.6.686.

Morris, M. C., Ciesla, J. A., & Garber, J. (2008). A prospective study of the cognitive-stress model of depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 719–734. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013741.

Nezu, A. M., & Carnevale, G. J. (1987). Interpersonal problem solving and coping reactions of Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 96(2), 155–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.96.2.155.

Rahim, M. A., Magner, N. C., & Shapiro, D. L. (2000). Do justice perceptions influence styles of handling conflict with supervisors? What justice perceptions, precisely? International Journal of Conflict Management, 11(1), 9–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022833.

Safford, S. M., Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., & Crossfield, A. G. (2007). Negative cognitive style as a predictor of negative life events in depression-prone individuals: A test of the stress generation hypothesis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 99, 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.003.

Şahin, N. H., & Durak, A. (1995). Stresle başa çıkma tarzları ölçeği: Üniversite öğrencileri için uyarlanması. Türk Psikoloji Dergisi, 10(34), 56–73.

Shahar, G., & Priel, B. (2003). Active vulnerability, adolescent distress, and the mediationing/suppressing role of life events. Personality and Individual Differences, 35, 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00185-X.

Shih, J. H., Abela, J. R. Z., & Starrs, C. (2009). Cognitive and interpersonal predictors of stress generation in children of affectively ill parents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9267-z.

Simons, A. D., Angell, K. L., Monroe, S. M., & Thase, M. E. (1993). Cognition and life stress in depression: Cognitive factors and the definition, rating, and generation of negative life events. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 584–591. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.102.4.584.

Tegin, B. (1980). Cognitive deficits in depression: Review based on Beck’s model (Doctoral dissertation). Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey.

Timbremont, B., & Braet, C. (2006). Brief report: A longitudinal investigation of the relation between a negative cognitive triad and depressive symptoms in youth. Journal of Adolescence, 29(3), 453–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.005.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Athanasios Mouratidis for his contributions to the organization of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keser, E., Kahya, Y. & Akın, B. Stress generation hypothesis of depressive symptoms in interpersonal stressful life events: The roles of cognitive triad and coping styles via structural equation modeling. Curr Psychol 39, 174–182 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9744-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9744-z