Abstract

Purpose

Few studies have examined the course of maternal depressive across pregnancy and early parenthood. The aim of this study was to identify the physical, sexual and social health factors associated with the trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum.

Method

Data were drawn from 1102 women participating in the Maternal Health Study, a prospective pregnancy cohort study in Melbourne, Australia. Self-administered questionnaires were completed at baseline (<24 weeks gestation), and at 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18 months, and 4 years postpartum.

Results

Latent class analysis modelling identified three distinct classes representing women who experienced minimal depressive symptoms (58.4%), subclinical symptoms (32.7%), and persistently high symptoms from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum (9.0%). Risk factors for subclinical and persistently high depressive symptoms were having migrated from a non-English speaking country, not being in paid employment during pregnancy, history of childhood physical abuse, history of depressive symptoms, partner relationship problems during pregnancy, exhaustion at 3 months postpartum, three or more sexual health problems at 3 months postpartum, and fear of a partner since birth at 6 months postpartum.

Conclusions

This study highlights the complexity of the relationships between emotional, physical, sexual and social health, and underscores the need for health professionals to ask women about their physical and sexual health, and consider the impact on their mental health throughout pregnancy and the early postpartum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depressive symptoms are common among women during the perinatal (pregnancy and first year after birth) and early parenting periods. Approximately, one in five women report depressive symptoms in the first 3 months following childbirth [1], and the proportion who remain depressed at 6- and 12 months postpartum is estimated to be 50 and 25%, respectively [2]. Although point prevalence estimates provide important information for policy and service planning, they do not capture changes in depressive symptoms over time for individual women (intra-individual changes). Improved understanding of the natural history of depression across the perinatal period, as well as the risk and protective factors for persistent patterns of depressive symptoms, will inform targeted intervention efforts during pregnancy to promote the mental health of women at risk of long-term difficulties.

Longitudinal studies of maternal postnatal depressive symptoms

A few studies have identified trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms across the perinatal period using increasingly popular person-centred approaches (i.e., latent class analysis and growth mixture modelling). In contrast to variable-centred approaches that describe relationships among variables (mean comparisons, correlation, and regression), person-centred approaches focus on relationships among individuals by classifying them into distinct groups based on individual response patterns [3]. For instance, a study of 4879 Australian women identified two trajectories of psychological distress over four time points from the first to seventh year postpartum [4]. The majority of women reported minimal symptoms over time (84%), but 16% reported persistently high and increasing symptoms over time. Risk factors for persistently high symptoms were younger maternal age at time of birth, being from a non-English speaking background, not completing high school, having a past history of depression, antidepressant use during pregnancy, child development problems, low parenting self-efficacy, poor relationship quality, and stressful life events. Although a broad range of social and contextual risk factors in the early postpartum were identified, this was a birth cohort study with no information available on antenatal mental health or contextual risk factors. This is an important consideration given that it is estimated that 18.4% of women experience depressive symptoms during pregnancy [1], and these symptoms are often associated with elevated symptoms in the postnatal period [5–7].

Several pregnancy cohort studies have identified trajectories of maternal depression from pregnancy. A United States study of 1735 women identified five trajectories of symptoms from pregnancy to 2 years postpartum [8]. The majority of women did not have depressive symptoms (71%); 9% had postnatal symptoms which resolved after the first postnatal year; 7% had chronic symptoms; and another 7% had late onset symptoms from 25 months postpartum. Women who had depression during pregnancy only comprised the smallest group (6%). Ethnicity, ambivalence about the pregnancy, and poor self-rated emotional health predicted class membership of the chronic, antenatal, and postnatal depression groups. High parity was associated with class membership of the chronic and postnatal depression groups. Being born in the United States of America was protective against membership of the antenatal and postnatal depression groups. Recent alcohol use uniquely predicted membership of the antenatal depression group. Finally, low educational attainment predicted membership of the postnatal and late onset groups. In another study of 579 women from pregnancy to 2 years postpartum [9], four trajectories were identified: the vast majority of women (72%) never reported depressive symptoms, 21% had clinically significant symptoms over time, with higher severity in pregnancy, 4% had symptoms only during the first year postpartum, and 3% had persistent high symptoms over time. Socio-economic factors reflecting disadvantage and high anxiety traits were predictive of depressive symptoms over time. The findings of both studies demonstrate that there is heterogeneity in the timing and persistence of depression symptoms during the perinatal period, and these different trajectories are associated with different correlates. Nonetheless, this study primarily focused on non-modifiable factors (e.g., ethnicity, parity, country of birth) and did not assess preconception factors that may be predictive of depressive symptoms during the perinatal period (e.g., history of sexual abuse).

More recently, six trajectories of depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 1-, 6-, and 12 months postpartum were identified for 2802 women in the First Baby Study [10]. Three trajectories represented women who experienced no or minimal depressive symptoms over time (85.2%), and two trajectories represented women who had persistently high levels of symptoms with only a slight improvement over time (13.2%). The smallest trajectory represented women who did report depressive symptoms in pregnancy but became increasingly depressed over the course of the first postnatal year (1.7%). History of anxiety or depression, marital status, and social support were significantly associated with the classes representing more severe and persistent symptoms over time. This is one of the few studies to examine mental health prior to conception in response to calls for longitudinal studies to investigate preconception risk factors for perinatal depression [5].

Five trajectories of depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 5 years were identified in the EDEN study with 1807 mothers in France [11]. The majority of women (60%) reported no depressive symptoms over time; 25.2% had persistent moderate symptoms; 5.0% reported persistently high depressive symptoms; 4.9% had high symptoms when their child was starting preschool only; and 4.7% reported high symptoms in pregnancy only. The factors associated with persistent depressive symptoms were being of non-French origin; childhood adversity (e.g., abuse or neglect); stressful life events during pregnancy; work stress; previous mental health problems and treatment; and high anxiety during pregnancy. Finally, in one of the longest running cohort studies of 329 mothers from pregnancy to 16–17 years after childbirth [12], four trajectories representing very low, low-stable, high-stable and intermittent symptoms over time as measured by the EPDS were identified. A range of antenatal predictors of the high-stable trajectory were identified including high EPDS scores during pregnancy, low life satisfaction, loneliness and negative expectations about their infants. Factors association with the intermittent trajectory included high EPDS scores during pregnancy, poor relationship with their own mother, and an urgent desire to conceive. Whilst the focus on social risk was more comprehensive than in these last two studies, they did not examine potentially important factors such as partner relationship problems, intimate partner abuse, or sexual or physical health problems.

Relationship, sexual and physical health problems as risk factors for perinatal depression

It is well established that couple relationship difficulties can have adverse consequences on maternal postnatal mental health [4]. A recent meta-analysis reported medium effect sizes associated with the relationship between conflict during pregnancy and high levels of antenatal and postnatal depression [13]. Women can also experience intimate partner abuse in the perinatal period, including fear of a partner, physical and sexual violence, emotional abuse such as threats and humiliation, economic restriction, and controlling behaviour [14]. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies reported that women who experience intimate partner abuse during pregnancy have threefold increased unadjusted odds of probable depression in the postnatal period [15]. The vast majority of studies are cross-sectional or have focused on the early perinatal period. A better understanding of the longitudinal associations between relationship difficulties, intimate partner abuse, and depressive symptoms beyond the postnatal period is needed.

Physical and sexual health problems are two areas of maternal health relatively neglected in the perinatal depression literature. In the first year after birth, physical health problems such as fatigue, perineal pain, back pain, urinary and faecal incontinence, haemorrhoids, and headaches and migraines are common [16–19]. Similarly, sexual health problems are common, with approximately 50% of women reporting problems such as lack of interest in sex, pain during sex, lack of lubrication and difficulty reaching orgasm in the first year after birth [20, 21]. Despite the high prevalence of physical and sexual health problems, few studies have examined associations with maternal mental health. Of those available, Woolhouse and colleagues [17] found that women reporting five or more physical health problems had a threefold increase in the likelihood of reporting depressive symptoms at 6–12 months postpartum. In a cross-sectional study of 468 women in London, those who were depressed were less likely to have not resumed intercourse at 6 months postpartum and more likely to report sexual health problems [22]. In a more recent study, women reporting pain during sex (dyspareunia) at 18 months postpartum had increased odds of concurrent depressive symptoms (OR 1.97, 95% CI 1.3–3.30) [21]. A better understanding of the longitudinal associations between physical and sexual health problems and depressive symptoms beyond the postnatal period is also needed to inform targeted intervention and prevention efforts to promote women’s mental health following childbirth and into the early years of parenting.

Aims of the current study

We sought to extend previous research to identify a broader range of factors associated with trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum. The first aim of the study was to identify distinct trajectories of depressive symptoms over time using longitudinal latent class analyses. Although this is a typically a data driven analysis, we hypothesised that we would identify at least three classes representing women with minimal or no symptoms, moderate symptoms and higher symptoms over time. The second aim was to identify preconception (e.g., childhood sexual abuse, termination of pregnancy), antenatal (e.g., partner relationship problems, sexual and physical health during pregnancy), and early postnatal (e.g., exhaustion, physical and sexual health problems) factors associated with the trajectories of depressive symptoms.

Method

Study design and sample

Data for this study were drawn from the Maternal Health Study, an Australian prospective cohort study investigating the mental and physical health of 1507 nulliparous women recruited during pregnancy. The study was approved by the relevant ethics committees of the participating hospitals, La Trobe University, and the Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne. Women registered to give birth at six metropolitan public hospitals in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia were recruited between April 2003 and December 2005. Eligibility criteria required women to (a) be nulliparous; (b) have an estimated gestation <24 weeks; (c) be sufficiently fluent in English to complete written questionnaires and telephone interviews; and (d) be aged 18 years or older. Mailed invitations containing information on the study, a consent form and baseline questionnaire were sent by hospital staff to women identified as eligible. Women who had not returned the questionnaire within 2 weeks were mailed a single reminder postcard. At following time points, data were collected via a combination of questionnaires and computer-assisted telephone interviews at 30–32 weeks gestation, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18 months postpartum, and 4 years postpartum.

Over 6000 women were invited to participate, of whom 1675 completed the baseline questionnaire. Of these, 1507 met eligibility criteria. It is not possible to determine the exact response rate as recruitment was facilitated by staff at the participating hospitals. The response rate is conservatively estimated to be between 21 and 28% based on the assumption that 80–90% of invitations reached eligible women. Retention rates at the follow-up time points range from 95% (late pregnancy) to 83% of the 1354 women who consented to the extended follow-up at 4 years postpartum. This paper reports on data collected at baseline, 3-, 6-, 12- and 18 months, and 4 years postpartum.

Measures

Depression symptoms were assessed during pregnancy and 3-, 6-, 12- and 18-months, and 4 years postpartum, using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale [EPDS; 23], a 10-item self-report measure designed to identify women at risk of depression during the perinatal period. Women were asked to indicate the extent to which they had experienced a range of symptoms in the past week on a 4-point scale. Scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating higher symptom severity. The recommended cut-off score of ≥13 [24] is indicative of a probable diagnosis of major depression. The EPDS has been validated for use with non-postnatal women and was found to be acceptable in a study of 232 pairs of non-postnatal (not pregnant and no birth in the previous 12 months; mean age of youngest child 3 years and 9 months) and postnatal women (had a birth in the previous 12 months) matched as close as possible on age, marital status, number of children and social class [25]. The EPDS and a clinical diagnostic interview were conducted, and the EPDS was found to have satisfactory sensitivity (79%) and specificity (85%). In the present study, the EPDS demonstrated high internal consistency at baseline (α = 0.87), 3 months (α = 0.87), 6 months (α = 0.89), 12 months (α = 0.88), 18 months (α = 0.89), and 4 years postpartum (α = 0.90).

Potential predictors of depression trajectories

A range of sociodemographic, preconception, antenatal and early postnatal factors potentially associated with trajectories of depressive symptoms were assessed as listed below.

Socio-demographic factors Demographic information was collected at enrolment during pregnancy and included maternal age (≥25 years = 1, ≤24 years = 0), maternal education (post-high school education year = 1; high school (year 12 or less = 2); country of birth (Australia = 1, English speaking Country = 2, non-English speaking country = 3); employment status (employed = 1, unemployed = 0); personal annual income ($AUD) at enrolment; relationship status (partnered = 1, not partnered = 2); and being a recipient of an Australian Government Health Care Concession Card (yes/no) as a marker of low income and eligibility for cheaper medicines and other concessions.

Preconception factors Women were asked whether they had ever experienced physical or sexual abuse during childhood using the Child Maltreatment History Self Report at 4 years postpartum [26] (no = 1, yes = 2). Women also reported on miscarriages or terminations prior to the current pregnancy, if they had ever been afraid of a partner (all rated as no = 1, yes = 2), and if they had experienced depressive or anxiety symptoms 12 months prior to the current pregnancy (never/rarely = 1, occasionally/often = 2). Women were also asked if they had experienced any of the following sexual health problems in the 12 months prior to their current pregnancy: lack of interest in sex, lack of lubrication, pain during sexual intercourse, pain on orgasm, vaginal tightness, vaginal looseness, bleeding or physical irritation after sex (None = 0, 1–2 problems = 1, 3+ problems = 2).

Antenatal factors During pregnancy, women were asked about the extent to which they had relationship problems with their partner (never/rarely = 1, occasionally = 2, often = 3), if they experienced fear of current or former partner (no = 1, yes = 2), and if they had sexual health problems (as per above). Cigarette smoking was categorised as (0 = non-smoking, 1 = quit during pregnancy, 2 = smoking).

Early postnatal factors At 3 months postpartum, exhaustion (never/rarely = 1, occasionally = 2, often = 3) and sexual health problems (as per above) were assessed. Women were asked if they had experienced any of the following health problems since birth: urinary incontinence, faecal incontinence, lower back pain, upper back pain, and painful or sore perineum (None = 0, 1–2 problems = 1, 3+ problems = 2). Finally, fear of a partner since the birth (no = 1, yes = 2) was assessed at 6 months postpartum. This single item question has been assessed as having good sensitivity and specificity for identifying women experiencing physical abuse or severe combined physical and sexual abuse, when compared to a multi-dimensional 30-item measure of intimate partner abuse [27].

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics for the sample demographics and study variables were computed using SPSS Version 22. Latent Class Analysis (LCA) was conducted to identify trajectories of women’s depressive symptoms across six time points (early pregnancy, 3, 6-, 12-, 18-months and 4 years) using MPlus Version 7.11 [28]. This involved identifying the smallest number of classes starting with a parsimonious 1-class model and fitting successive models with increasing numbers of classes. Model solutions were compared using Likelihood ratio statistic (L 2), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) across the successive models. Better fitting models have lower L 2, BIC, and AIC values. Entropy is an index for assessing the precision of assigning latent class membership, with higher probability values indicating greater precisions of classification. Posterior probabilities are also obtained for each case indicating the probability of belonging to each class. The Vuong-Lo-Mendall-Rubin likelihood ratio test was also used to test for significant differences between the models. Class membership was recorded and used in the logistic regression analyses to identify factors associated with the identified latent classes. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression models were estimated, and results are presented as odd ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

Missing data on the EPDS were managed using Full Information Maximum Likelihood in Mplus Version 7.11 when estimating the trajectories of depressive symptoms, and multiple imputation in SPSS for variables used in the logistic regression analyses. We imputed 20 complete datasets using a multivariate normal model incorporating the all variables used in the analyses. Pooled estimates for all proportions and model parameter estimates were obtained using SPSS, which average the results using Rubin’s rules. All analyses were conducted using the total sample with imputed data, and only cases with complete data. Given that the analyses yielded similar results, only those using imputed data are presented here.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 1507 women met the eligibility criteria and returned the baseline questionnaire. Demographic characteristics for the entire sample at enrolment are presented in Table 1. The majority of women enrolled in the study were born in Australia, between 25 and 34 years of age, married or living with a partner, tertiary educated, and in paid employment during pregnancy.

Study participants were compared to women giving birth at the participating hospitals using routinely collected perinatal data. This showed that the sample was largely representative in relation to important obstetric covariates, including method of birth and infant birthweight. However, younger women (under 25 years) and women born overseas of non-English speaking background were under-represented. Further details regarding the study sample are available in an earlier paper [29]. Over the course of the study, 126 participants dropped out or were lost to follow-up. Reasons include: participant declined further participation (n = 65), participant unable to be contacted (n = 29), participant too busy (n = 21), stillbirth (n = 6), infant death (n = 2), infant ill health (n = 2), and maternal ill health (n = 1). The number of surveys returned at the 3-, 6-, 12-, 18-month and 4-year follow-ups were 1431, 1400, 1357, 1327, and 1102, respectively. Selective attrition was observed between 6 months and 4 years, whereby women completing the 4-year follow-up were more likely to be Australian-born, older, tertiary-educated, not on a government benefit in early pregnancy, and less likely to have reported depressive symptoms.

Depressive symptoms in the perinatal and early parenting period

The extent of missing data on the EPDS was approximately 11% across all waves. Missing data was highest at 4 years postpartum (27.2%) due to reasons described above. Descriptive statistics and correlations for the EPDS scores at each time point are presented in Table 2. The proportion of women who reported EPDS scores at the clinical cut-point of 13 and above is also presented.

Latent class analysis to describe trajectories of depressive symptoms over time

Longitudinal latent class models specifying 1–5 models were estimated (Table 3). Although the model fit indexes (L 2, AIC, BIC) continued to decrease as class size increased, the 3-class model was accepted as the final model after examining all indexes and tests of model fit for several reasons. First, the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test indicated a significant difference between the 2- and 3-class models, suggesting that the 3-class model gives significant improvement in fit over the 2-class model. Second, the entropy value for the 3-class model was good (0.82) and the classification probabilities for latent class membership were high (Class 1 −0.94; Class 2 −0.87; Class 3 −0.91), suggesting acceptable precision in assigning individual cases to their appropriate class. Finally, a 3-class solution made clinical sense, representing women who experienced few depressive symptoms over time, those who reported persistently high symptoms, and those who reported subclinical levels over time.

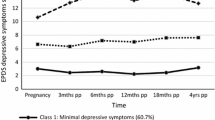

Figure 1 illustrates the estimated means for the three classes of depressive symptoms over time. The first and largest trajectory consisted of women who reported ‘Minimal Depressive Symptoms’ from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum (n = 879, 58.4%). The estimated means and 95% confidence intervals for this class were as follows for pregnancy (3.16, 95% CI 2.87, 3.45), 3 months postpartum (2.51, 95% CI 2.25, 2.78), 6 months postpartum (2.52, 95% CI 2.27, 2.77), 12 months postpartum (2.36, 95% CI 2.10, 2.61), 18 months postpartum (2.48, 95% CI 2.12, 2.76), and 48 months postpartum (3.18, 95% CI 2.83, 3.53).

The second trajectory consisted of women who reported ‘Subclinical Depressive Symptoms’ over time (n = 492, 32.7%). The estimated means and 95% confidence intervals for this class were as follows for pregnancy (6.78, 95% CI 6.23, 7.33), 3 months postpartum (6.47, 95% CI 6.02, 6.92), 6 months postpartum (7.71, 95% CI 7.12, 8.29), 12 months postpartum (7.18, 95% CI 6.55, 7.82), 18 months postpartum (7.77, 95% CI 7.13, 8.41), and 48 months postpartum (7.75, 95% CI 7.05, 8.46).

The third and smallest trajectory consisted of women who reported ‘Persistently High Depressive Symptoms’ over time (n = 135, 9.0%). The estimated means and 95% confidence intervals for this class were as follows for pregnancy (12.07, 95% CI 10.76, 13.39), 3 months postpartum (13.49, 95% CI 12.21, 14.78), 6 months postpartum (14.73, 95% CI 13.47, 15.99), 12 months postpartum (13.83, 95% CI 12.72, 14.94), 18 months postpartum (14.04, 95% CI 12.79, 15.30), and 48 months postpartum (13.02, 95% CI 11.57, 14.46).

Predictors of course of depressive symptoms over time

The extent of missing data was approximately 7% across all the potential predictor variables, and on average approximately 4% for the relationship, physical and sexual health variables specifically. Missing data were highest for childhood physical and sexual abuse (26.9%) as this was asked about in the 4-year follow-up when attrition was highest. Missing data were handled using multiple imputation described above. Demographic, ante- and postnatal characteristics for each of the three latent classes are presented in Table 4.

Table 4 also presents the multinomial logistic regression analyses examining the bivariate relationships between each potential predictor variable and the Subclinical Symptoms and Persistently High Symptoms classes with the Minimal Symptoms class as the reference category. Compared to women in Minimal Symptoms class, women in the Subclinical Symptoms and Persistently High Symptoms classes had higher odds of: being under 24 years of age; not having a partner; not being in paid employment; having an income less than AUD$40,000; having a childhood history of physical and/or sexual abuse; having a history of depressive and/or anxiety symptoms prior to the current pregnancy; having been afraid of a current or ex-partner, experiencing sexual health problems; reporting relationship problems during pregnancy; and experiencing exhaustion and physical health problems in the early postpartum. Women in the Persistently High Symptoms class also had higher odds of being from a non-English speaking background, and smoking or having quit smoking during the current pregnancy compared to women in the Minimal Depressive Symptoms class.

Table 4 also presents the multivariable multinomial logistic regression analyses identifying the strongest predictors associated with the Subclinical Symptoms and Persistently High Symptoms classes compared to the Minimal Symptoms class as the reference category. Compared to women in Minimal Depressive Symptoms class, women in the Subclinical Symptoms class had higher odds of: being under 24 years of age at the time of having their first baby; being from a non-English speaking background; not in paid employment during early pregnancy; having a childhood history of physical abuse; experiencing depressive symptoms prior to the current pregnancy; experiencing occasional relationship problems during pregnancy; experiencing three or more sexual health problems during pregnancy and the early postpartum; experiencing exhaustion and three or more physical health problems in the early postpartum; and being afraid of a partner in the 6 months after birth.

Compared to women in Minimal Depressive Symptoms class, women in the Persistently High Symptoms class had higher odds of: being from a non-English speaking background; not in paid employment during early pregnancy; having a childhood history of physical abuse; experiencing depressive symptoms prior to the current pregnancy; experiencing relationship problems during pregnancy; experiencing three or more sexual health problems during the early postpartum only; experiencing exhaustion in the early postpartum; and being afraid of a partner in the 6 months after birth.

Discussion

Drawing on data from a large prospective study of Australian first time mothers recruited in pregnancy, this study aimed to examine trajectories of depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum, and identify associated preconception, antenatal, and early postpartum risk factors. As hypothesised, we did identify at least three groups of women with distinct trajectories of depressive symptoms over time: 58.4% of women reported no or minimal depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum (EPDS scores 2–4), 32.7% reported subclinical symptoms (EPDS scores 6–8), and 9.0% reported persistently high symptoms (EPDS scores 12–15). In contrast to other pregnancy cohort studies [8–12], we identified fewer classes and we did not identify classes of women whose symptoms resolved over time, or those who had late onset symptoms. Classes representing these patterns were very small in previous studies (ranging from 1 to 7%), and it is likely that our cohort sample size did not permit the identification of such small meaningful classes.

Despite this, consistent with other studies, we identified classes of women with persistent moderate and high symptoms over time, highlighting the stable and enduring nature of depressive symptoms across the perinatal and early years of parenting for some women. The chronicity of moderate to severe symptoms for over 40% of women in our study is concerning given the burgeoning literature on the adverse consequences of maternal depression for women’s and children’s health outcomes [21, 30]. Even subclinical depressive symptoms pose a significant burden for women with reduced capacity to carry out usual household and workplace responsibilities [31], increased health service use [32]. Subclinical depressive symptoms are also associated with increased emotional and behavioural difficulties for children [33]. This underlines the importance of identifying women most at risk of enduring subclinical and clinical levels of depressive symptoms, and the need for targeted intervention strategies to promote their mental health.

To inform the development of targeted early identification and treatment approaches, we identified a complex array of risk factors during the antenatal and early postnatal period associated with the depression trajectories. Several are well established social risk factors. For instance, compared to women experiencing minimal depressive symptoms over time, those with an enduring subclinical and high pattern of symptoms over time were more likely to have migrated from a non-English speaking country, not be in paid employment during pregnancy, have a history of childhood physical abuse, and have a history of depressive symptom. Our finding that partner relationship problems and fear of partner in the ante- and postnatal period is associated with enduring subclinical and clinical symptoms from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum extends meta-analytic findings demonstrating associations between intimate partner violence during pregnancy and depression in the 12 months following childbirth [15].

Our study also provides new evidence regarding common physical and sexual health issues associated with persisting maternal depressive symptoms. Physical and sexual health problems are common during pregnancy and after childbirth, but few studies have sought to understand the potential impact or relationship with mental health. We recognize that some physical and sexual health problems such as lack of interest in sex and pain are often symptoms of depressive disorders; however, in this study we examined specific health problems that are very common during pregnancy and childbirth such as back pain, urinary and faecal incontinence, and perineal pain, lack of lubrication, pain during sexual intercourse, pain on orgasm, vaginal tightness, vaginal looseness, bleeding or physical irritation after sex. Compared to women who experienced minimal symptoms, women with enduring subclinical symptoms were more likely to report three or more sexual and physical health problems during pregnancy and 3 months postpartum, and women with persistent high symptoms were more likely to report three or more sexual health problems in the early postpartum. This highlights the complexity of the relationship between emotional, physical and sexual health, which has been recognised by the World Health Organisation, and underscores the need for health professionals to ask women about their physical and sexual health, and consider the impact on their mental health throughout pregnancy and the early postpartum.

Strengths, limitations and future research directions

A key strength of this study was rich data drawn from a pregnancy cohort of more than 1500 women who provided rich information about their health, wellbeing, and relationships from pregnancy into the early years of parenting. Longitudinal analyses enabled modelling of the individual women’s (intra-individual) changes in depressive symptoms over time. Nonetheless, the findings of this study should be interpreted within the context of some important limitations. First, the majority of women enrolled in the study were born in Australia, older than 25 years of age, partnered, tertiary educated, and in paid employment; therefore, limiting generalizability of the findings to under-represented women who are young, unpartnered, and born overseas in a non-English speaking country. Similarly, selective attrition was observed among younger women with lower educational attainment. Furthermore, women lost to follow-up were more likely to report higher levels of antenatal depressive symptoms than those who remained in the study. Therefore, it is likely that our study underestimates the true prevalence of persisting symptoms. However, this is unlikely to result in biased estimates of exposure-outcome associations.

Second, there are limitations pertaining to the measures used in this study. Depressive symptoms at 4 years postpartum were assessed using the EPDS. Although the EPDS has been validated for use with non-postnatal women in one study [25], further validation of the scale compared to other commonly used instruments to assess depressive symptoms in the general population (i.e., Beck Depression Inventory, Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) is needed. Further to this, in some instances brief measures were used (e.g., a single item to assess fear of current partner at several time points) and may have led to an underestimation of the strength of the relationships between some variables and class membership. Moreover, although we sought to account for other psychosocial and demographic factors known to be associated with depressive symptoms (e.g., country of birth, adverse childhood events, past history of anxiety and depressive symptoms), there are other factors such as social support that were not included in our models. Future research could focus on resilience-promoting factors such as social support that may moderate associations between relationship, physical and sexual risk factors and trajectories of depressive symptoms.

The third set of issues relate to the timing of measures. The retrospective report of preconception factors may mean that these measures were affected by recall bias. Although current depressive symptoms such as negative affect and cognitions might influence negative recollections of relationships, events and health in the past, this is a complex issue to disentangle as it is well established that childhood history of adverse events and poor health influence later mental health [34]. Another complex issue is the likely bidirectional relationships between depressive symptoms, physical and sexual health during pregnancy and particularly after childbirth. In this study, we sought to take a first look at how these factors relate to trajectories of depressive symptoms over time. It is likely that some factors measured may be maintaining as well as precipitating factors for depressive symptoms. Future research using cross-lagged models to explore the reciprocal relationships between depressive symptoms, physical and sexual health problems may help to elucidate more specific directional effects and causal pathways.

Implications and conclusions

Our study findings have important implications for the timing and frequency of screening for maternal perinatal depression. The Marcé Society for Perinatal Mental Health recommends that screening ideally occurs both in pregnancy and in the immediate postpartum (e.g., 3 months after childbirth) [35]. The persistent nature of symptoms experienced by many women in the current study underscores the importance of ongoing opportunities to identify and monitor women at risk and link them into mental health support beyond the perinatal period and into the early years of parenting.

Many risk factors (e.g. common maternal physical health problems, sexual health issues, fear of partner) associated with the enduring patterns of moderate and severe depressive symptoms are able to be identified readily by health professionals in contact with women during pregnancy and the postnatal period. This could provide the basis for further inquiry about maternal mental health and tailored intervention strategies addressing modifiable factors. Whilst some risk factors are not modifiable (i.e., history of physical or sexual abuse during childhood, age at time of pregnancy), many of those identified are potentially modifiable with appropriate intervention. Yet, maternal physical health problems, sexual health issues, intimate partner violence and relationship difficulties are rarely explored in antenatal or postnatal care, or seen as relevant to a whole of family approach in early childhood services. A more detailed and thorough approach to psychosocial assessment and surveillance of maternal health during and after pregnancy is warranted. Greater attention to these issues, and appropriately tailored intervention strategies addressing common maternal physical health problems, sexual health issues and difficulties in intimate partner relationships is likely to result in improved maternal mental health at a population level, as demonstrated by the trial conducted by MacArthur and colleagues [36].

The need for identifying and responding to women experiencing intimate partner abuse is well recognised. Universal health services such as general practice, maternity hospitals, and maternal and child health services are in an ideal position to identify and support women experience partner violence. The World Health Organisation recommend that women should be asked about violence when there are indicators such as poor mental health (depression, anxiety, and suicidality), physical health problems (chronic pain, injuries, diarrhoea), or sexual health problems [37]. Despite this recommendation, the inquiry rate by health professionals is low (approximately one in ten) [38], and a significant gap in knowledge and evidence about the best ways to identify and support women experiencing partner violence remains.

The development of multi-faceted, tailored interventions that are responsive to women’s social contexts is needed. For instance, women with subclinical depressive symptoms may benefit from brief interventions such as (e.g., ‘web-based interventions such as MumMoodBooster’ [39]), short-term counselling interventions, whilst women experiencing enduring clinical symptoms may benefit from more intensive interventions that involve inter-agency collaboration and coordination to address complex constellations of social risk factors. Policy and intervention efforts targeting the promotion of women’s mental health in the early years of their children’s lives is an important step to promoting intergenerational health and wellbeing.

References

Gavin NI et al (2005) Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol 106:1071–1083

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2007) Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Manchester

Laursen BP, Hoff E (2006) Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill Palmer Q 52(3):377–389

Giallo R, Cooklin A, Nicholson JM (2014) Risk factors associated with trajectories of mothers’ depressive symptoms across the early parenting period: an Australian population-based longitudinal study. Arch Womens Ment Health 17:115–125

Vliegen N, Casalin S, Luyten P (2014) The course of postpartum depression: a review of longitudinal studies. Harv Rev Psychiatry 22(1):1–22

Gaillard A et al (2014) Predictors of postpartum depression: prospective study of 264 women followed during pregnancy and postpartum. Psychiatry Res 215(2):341–346

Banti S et al (2011) From the third month of pregnancy to 1 year postpartum. Prevalence, incidence, recurrence, and new onset of depression. Results from the Perinatal Depression-Research & Screening Unit study. Compr Psychiatry 52(4):343–351

Mora PA et al (2009) Distinct trajectories of perinatal depressive symptomatology: evidence from growth mixture modeling. Am J Epidemiol 169(1):24–32

Sutter-Dallay AL et al (2012) Evolution of perinatal depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 2 years postpartum in a low-risk sample: the MATQUID cohort. J Affect Disord 139:23–29

McCall-Hosenfeld J, Phiri K, Schaefer E, Junjia Z, Kjerulff K (2016) Trajectories of depressive symptoms throughout the peri- and postpartum period: results from the First Baby Study. J Womens Health 25:1112–1121

Van der Waerden J et al (2015) Predictors of persistent maternal depression trajectories in early childhood: results from the EDEN mother–child cohort study in France. Psychol Med 45(09):1999–2012

Ilona L et al (2015) Long-term trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms and their antenatal predictors. J Affect Disord 170:30–38

Pilkington PD, Whelan TA, Milne LC (2015) A review of partner-inclusive interventions for preventing postnatal depression and anxiety. Clin Psychol 19:63–75

Rivas C, Ramsay J, Sadowski L, Davidson LL, Dunne D, Eldridge S, Hegarty K, Taft A, Feder G (2015) Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (12), art ID CD005043. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005043.pub3

Howard LM et al (2013) Domestic violence and perinatal mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 10(5):1–16

Cooklin AR et al (2015) Maternal physical health symptoms in the first 8 weeks postpartum among primiparous Australian women. Birth 42(3):254–260

Woolhouse H et al (2014) Physical health after childbirth and maternal depression in the first 12 months post partum: results of an Australian nulliparous pregnancy cohort study. Midwifery 30(3):378–384

Brown S, Lumley J (2000) Physical health problems after childbirth and maternal depression at six to seven months postpartum. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 107(10):1194–1201

Gartland D et al (2010) Women’s health in early pregnancy: findings from an Australian nulliparous cohort study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 50(5):413–418

Glazener CM (1997) Sexual function after childbirth: women’s experiences, persistent morbidity and lack of professional recognition. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 104:330–335

McDonald E, Woolhouse H, Brown S (2015) Consultation about sexual health issues in the year after childbirth: a cohort study. Birth 42:354–361

Morof D et al (2003) Postnatal depression and sexual health after childbirth. Obstet Gynecol 102(6):1318–1325

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 150(6):782–786

Murray D, Cox JL (1990) Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EDDS). J Reprod Infant Psychol 8(2):99–107

Cox J et al (1996) Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in non-postnatal women. J Affect Disord 39:185–189

MacMillan HL et al (2013) Child physical and sexual abuse in a community sample of young adults: results from the Ontario Child Health Study. Child Abuse Negl 37:14–21

Hegarty K (1999) Measuring a multidimensional definition of domestic violence: prevalence of partner abuse in women attending general practice. University of Queensland, Brisbane

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2015) Mplus User’s Guide, Seventh Edition. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Brown S et al (2006) Maternal health study: a prospective cohort study of nulliparous women recruited in early pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 6:12

Davalos DB, Yadon C, Tregellas H (2012) Untreated prenatal maternal depression and the potential risks to offspring: a review. Arch Womens Ment Health 15:1–14

Backenstrass M et al (2006) A comparative study of nonspecific depressive symptoms and minor depression regarding functional impairment and associated characteristics in primary care. Compr Psychiatry 47:35–41

Cuijpers P, de Graaf R, van Dorsselaer S (2004) Minor depression: risk profiles, functional disability, health care use and risk of developing major depression. J Affect Disord 79:71–79

Giallo R et al (2015) The emotional-behavioural functioning of children exposed to maternal depressive symptoms across pregnancy and early childhood: a prospective Australian pregnancy cohort study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24:1233–1244

Gartland D et al (2016) Vulnerability to intimate partner violence and poor mental health in the first 4-year postpartum among mothers reporting childhood abuse: an Australian pregnancy cohort study. Arch Women’s Ment Health 19:1091–1100

Austin M-P, Marcé Society Position Statement Advisory Committee (2014) Marcé International Society position statement on psychosocial assessment and depression screening in perinatal women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 28:179–187

MacArthur C et al (2002) Effects of redesigned community postnatal care on womens’ health 4 months after birth: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 359:378–385

World Health Organization (2013) Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines. WHO, Geneva

Hegarty K, Feder G, Ramsay J (2006) Identification of partner abuse in health care settings: should health professionals be screening? In: Roberts G, Hegarty K, Feder G (eds) Intimate partner abuse and health professionals. Elsevier, London, pp 79–92

Danaher BG, Milgrom J, Seeley JR, Stuart S, Schembri C, Tyler MS, Ericksen J, Lester W, Gemmill AW, Kosty DB, Lewinsohn P (2013) MomMoodBooster web-based intervention for postpartum depression: feasibility trial results. J Med Internet Res 15(11):e242. doi:10.2196/jmir.2876

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), VicHealth, and the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. RG and SB were supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship and a NHMRC Research Fellowship, respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giallo, R., Pilkington, P., McDonald, E. et al. Physical, sexual and social health factors associated with the trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 52, 815–828 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1387-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1387-8