Abstract

Children exposed to maternal depression during pregnancy and in the postnatal period are at increased risk of a range of health, wellbeing and development problems. However, few studies have examined the course of maternal depressive symptoms in the perinatal period and beyond on children’s wellbeing. The present study aimed to explore the relationship between both the severity and chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms across the early childhood period and children’s emotional–behavioural difficulties at 4 years of age. Data from over 1,085 mothers and children participating in a large Australian prospective pregnancy cohort were used. Latent class analysis identified three distinct trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum: (1) no or few symptoms (61 %), (2) persistent subclinical symptoms (30 %), and (3) increasing and persistently high symptoms (9 %). Regression analyses revealed that children of mothers experiencing subclinical and increasing and persistently high symptoms were at least two times more likely to have emotional–behavioural difficulties than children of mothers reporting minimal symptoms, even after accounting for known risk factors for poor outcomes for children. These findings challenge policy makers and health professionals to consider how they can tailor care and support to mothers experiencing a broader spectrum of depressive symptoms across the early childhood period, to maximize opportunities to improve both short-and long-term maternal and child health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Accumulating evidence suggests that early life exposure to stress and adversity can lead to lifelong changes in children’s nervous, immune and endocrine systems, increasing their risk for poor health across the lifespan [1]. It is not surprising then that the vast majority of studies have examined the impact of the severity of maternal depressive symptoms on children’s health and development during potentially critical periods such as pregnancy and the early postnatal period. Evidence for the adverse effects of pre- and postnatal symptoms on children is unequivocal, with systematic reviews reporting increased risks of poorer cognitive functioning, speech and language problems, poorer physical health, and internalizing and externalizing behaviour problems from infancy to adolescence [2–4]. Few studies, however, have examined both the severity and chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms beyond the perinatal period on children’s outcomes. This is an important given research demonstrating that symptoms can persist beyond the perinatal period for many women [5, 6].

Depression affects up to 25 % of women during pregnancy [7] and 10–15 % during the first postnatal year [8–10], with a further 30–50 % reporting subclinical levels of symptoms [11, 12]. Depressive symptoms tend to be episodic in the postpartum period, and it has been estimated that approximately one-third of women continue to experience symptoms at 12 months [13–15] and 2 years postpartum [16, 17]. Data from the Maternal Health Study (also used in the present study), found that 15 % of 1,500 women had clinically significant levels of depression at 4 years postpartum, and that 27 % of these had reported symptoms in early pregnancy, and 48 % had reported symptoms on at least one occasion in the first 12 months postpartum [6]. These findings highlight that depressive symptoms persist for many women, and that a considerable proportion of children are living with mothers experiencing mental health difficulties across the early childhood period.

These findings also highlight marked variability in the course of depressive symptoms across the perinatal period and beyond. A key methodological consideration for longitudinal research tracking symptoms over time is the appropriateness of using predefined cut-off scores to identify subgroups of women showing no symptoms, episodic or chronic symptoms. Cents and colleagues [18] recently argued that this approach tends to under- or over-fit patterns in the data by forcing individuals into predefined trajectory groups [18]. This may fail to capture adequately the wide variability in the expression of depressive symptoms ranging from mild and transitory distress to episodically severe, or persisting and clinically significant symptoms across time. As an alternative, statistical approaches, such as latent class analysis (LCA) that permit the simultaneous modelling of both severity and course of maternal depressive symptoms, have been advocated [18–20]. LCA posits that a large heterogeneous group can be reduced to several homogeneous subgroups or classes based on their profile of observed symptoms.

Several studies have employed this approach to identify distinct trajectories of symptoms from the postnatal period and beyond. For instance, Mora et al. [21] identified five trajectories of symptoms over four time points from pregnancy to 2 years postpartum among 1,735 women in the US [21]. The majority of women did not have depressive symptoms (71 %); 9 % had postnatal symptoms which resolved after the first postnatal year; 7 % had chronic symptoms, and another 7 % had late onset symptoms from 25 months postpartum. The final and smallest group of women only had depression during pregnancy (6 %). In contrast and most recently, Giallo et al. [5] identified two trajectories of symptoms over four time points from 1 to 7 years postpartum for 4,879 Australian women. The majority of women were assigned to the minimal symptoms class (84 %), and 16 % reported persistently high and increasing symptoms over time. The LCA approaches used in these studies capture heterogeneity in both the severity and chronicity of symptoms over time. Research using these approaches provides an opportunity to explore the cumulative effects of symptoms of varying severity on children’s outcomes.

Two recently conducted systematic reviews report that maternal mental health problems during pregnancy and in the first postnatal year are associated with increased risks of developmental delays, cognitive difficulties, increased stress sensitivity, internalizing and externalizing behaviours, asthma, atopic allergy, and obesity for infants, toddlers, and school-aged children [4, 22]. Whilst this highlights that the pre- and postnatal period is a time of increased risk, few studies have examined the chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms beyond the perinatal period. Of those conducted [23, 24], predefined clinical cut-offs have been used rather than the alternative approach described above. As expected, these studies found that children exposed to chronic, clinically significant depressive symptoms were at increased risk of emotional–behavioural difficulties. Whilst these findings are important, it is not clear whether these adverse outcomes are experienced primarily by children exposed to clinically significant symptoms, or whether they are also evident for children exposed to lower, subclinical levels of depressive symptoms, which are more common.

To address this issue, three studies have conducted latent class modelling to identify trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms, and examine their association with long-term emotional–behavioural outcomes for children [18, 25, 26]. In a US study of 1,261 women and their children, six trajectories over seven time points from 1 to 7 years postpartum were identified [25]: (1) high chronic (2.5 %), (2) moderate increasing (6 %), (3) high decreasing (5.6 %), (4) intermittent (4 %), (5) moderate stable (36 %), and (6) low stable (46 %). At the age of 7 years and after accounting for salient demographic factors, mothers who reported the highest levels of symptoms (chronic, moderate increasing and high decreasing) rated their children as having more internalizing, externalizing, and social competence problems than mothers reporting low or moderate levels of depression. In a later US study, with a sample of 1,364 women and their children, five trajectories over ten time points from 1 to 12 years postpartum were identified [26]: (1) chronic high depressive symptoms (5 %), (2) early symptoms up to 2 years postpartum which then declined and remained low at subclinical levels (5 %), (3) moderately elevated symptoms (11 %), (4) stable subclinical symptoms (30 %), and (5) never depressed (48.5 %). Similarly, at the age of 15 years and after accounting for demographic characteristics, children exposed to chronic symptoms, moderately elevated, and stable subclinical symptoms self-reported more internalizing and externalizing behaviour difficulties than children whose mothers were never depressed.

Building on these previous studies to include a measure of depression during pregnancy, Cents et al. [18] recently reported on depressive symptoms at four time points from pregnancy to 3 years postpartum for 4,167 women in the Netherlands [18]. Four classes were identified, representing women with no depressive symptoms (34 %), low symptoms (54 %), moderate symptoms (11 %), and high symptoms (1.5 %). Results revealed that at age 3 years, children of mothers who reported either low, moderate or high depressive symptoms over time had significantly more internalizing and externalizing problems than children of mothers assigned to the no depressive symptoms class. Although these findings suggest that exposure to persistent depressive symptoms even at low levels are associated with adverse emotional–behavioural outcomes for children, the evidence remains thin. Furthermore, whilst these studies accounted for demographic factors often associated with poor emotional–behavioural outcomes for children such as maternal age, education level, income, and marital status, they failed to examine a broader range of psychosocial risk factors associated with children’s outcomes such as life stress and adversity and quality of the couple relationship.

The current study addresses these limitations by drawing upon longitudinal data from a large Australian prospective pregnancy cohort of over 1,000 women and children to explore the relationship between both the severity and chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms and children’s emotional–behavioural difficulties at the age of 4 years. The aims of the study were twofold. First, we aimed to identify distinct groups of women defined by their trajectories of depressive symptoms across five points from early pregnancy to 4 years postpartum. Second, we sought to examine the associations between trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms and children’s emotional and behavioural outcomes at the age of 4 years whilst accounting for a range of psychosocial factors associated with children’s emotional–behavioural functioning such as stressful life events [27], quality of the couple relationship [28], maternal involvement in home learning activities with their children [29], and partner involvement in caregiving [30].

Materials and methods

Study design

Data for this study were drawn from the Maternal Health Study (MHS), a prospective longitudinal study of women’s physical and psychological health during pregnancy and after childbirth. Ethics approval was sought from the participating hospitals, La Trobe University and The Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne. The published study protocol details the study design, sampling and field methods [31]. In summary, women registered to give birth at six metropolitan public hospitals in Melbourne, Australia between April 2003 and December 2005, were recruited to the study. The eligibility criteria were: (a) 18 years or older; (b) nulliparity (i.e., no prior live births or pregnancies ending in a stillbirth); (c) estimated gestation of up to 24 weeks at the time of enrolment, and (d) proficiency in English to complete written questionnaires and participate in telephone interviews. Data were collected via self-administrated questionnaires and computer-assisted interviews during pregnancy at (a) 10–24 weeks’ gestation, (b) 30–32 weeks’ gestation, (c) 3, 6, 9, 12, and 18 months postpartum, and (d) when the index (firstborn) child was 4 years of age.

Approximately 6,000 invitations to participate in the study were mailed to women via the six participating hospitals. It was not possible to determine how many ineligible women received an invitation, how many invitations were incorrectly addressed, or how many women received more than one invitation. There were 1,507 who met baseline eligibility and returned a baseline questionnaire. Assuming that 80–90 % of invitations reached eligible women, we conservatively estimate that the response rate was between 28 and 31 %. Excellent retention rates were achieved at all follow-ups ranging from 98 % (n = 1,483) in late pregnancy to 83.4 % (n = 1,102) at 4 years postpartum. This paper draws on data collected in the self-administered questionnaires completed during early pregnancy (10–24 weeks gestation), at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months postpartum, and at 4 years postpartum.

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed in all follow-up questionnaires using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). This 10-item self-report measure was designed to identify women at risk for depression in the postnatal period [32], and later validated for use in pregnancy [33].Women were asked to indicate whether the extent to which they had experienced a range of symptoms such as depressed mood, crying, difficulty sleeping, feeling worried or anxious, and thoughts of self-harm in the previous week on a 4-point scale. A cut-off score of ≥13 is recommended when screening for probable major depression [33]. Cronbach’s alphas for the current sample at each time point are presented in Table 2.

Children’s emotional and behavioural difficulties

Children’s emotional and behavioural difficulties were assessed at 4 years of age using the parent-report of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; [34, 35]. The SDQ is comprised of 25 items assessing a range of emotional and behavioural symptoms such as sadness, worries, attention difficulties, fighting, and problems with peers. The items were rated on a 3-point scale, ranging from 0 = not true to 2 = certainly true, with higher scores indicating more emotional and behavioural difficulties. There are five subscales assessing emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer problems and prosocial behaviour, and a total difficulties scale. For each scale, there are pre-defined cut-off scores for scores in the ‘normal’, ‘at risk’, and ‘clinical’ range based on Australian norms (see www.sdqinfo.com). The SDQ has had extensive psychometric evaluation with Australian samples, with moderate to strong internal consistency and test–retest reliability reported [36]. Cronbach’s alphas for the subscales and total difficulties scale for the current sample are presented in Table 2. Given that the reliability estimates were not acceptable for the subscales, the total difficulties scale was used in the present study.

Covariates

Information pertaining to a range of demographic, child and psychosocial factors were collected during pregnancy, at 6 months and 4 years postpartum. These included maternal age, country of birth, relationship status, highest educational attainment, employment status and hours per week, personal income, child gender, whether they had subsequent children, smoked during pregnancy, or had concerns for their baby’s health at 6 months postpartum. Women were also asked if they received paid parental leave from their employer following the birth of their baby. In Australia, at the time of data collection, the amount of paid leave available was set by individual employers and could vary considerably from no to several months paid leave. There was no legislation stating minimum amount of leave to be paid, and no government contributions to paid maternity leave provided. We coded access to some paid leave as yes or no. Maternal relationship transitions were identified as a change in relationship status across the follow-up time points, where 0 = no relationship transitions and 1 = at least one relationship transition. Perceived emotional satisfaction in their couple relationship was assessed at 6 months and 4 years postpartum using a single item, ranging from 1—extremely satisfied to 5—not at all satisfied (recoded as 0—high satisfaction and 1—low satisfaction). Women not in a relationship were assigned a score of 1. Perceptions of partners’ involvement in parenting was also assessed at 6 months and 4 years postpartum using a single item, ranging from 1—yes definitely involved to 3—no, not involved (recoded as 0—limited involvement and 1—high involvement).

Stressful life events were assessed drawing on items from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring Study (PRAMS) [37] and a review of the impact of life events and social health issues in the perinatal period. At 4 years postpartum, women were asked if they had experienced several major life events including separation and divorce, moving house, losing a job, or serious family conflict in the last 12 months. Maternal involvement in home activities was assessed at 4 years using a five-item scale from the Growing up in Australia: Longitudinal study of Australian children [38]. Mothers were asked to indicate how many days in the past week (1 = none, 2 = 1–2 days, 3 = 3–5 days, 4 = 6–7 days) they had engaged in a range of activities with their children such as read from a book and involved them in everyday activities. Items were summed with higher scores indicating greater involvement in home activities.

Data analysis

Analyses were conducted in three stages to investigate the aims of the study. First, LCA was conducted to identify trajectories of women’s depressive symptoms across six time points (early pregnancy, 3, 6, 12, 18 months and 4 years) using MPlus Version 7.11 [39]. This involves identifying the smallest number of classes starting with a parsimonious 1-class model and fitting successive models with increasing numbers of classes. Model solutions were evaluated by comparing Likelihood ratio statistic (L 2), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) across the successive models. Better fitting models have lower L 2, BIC, and AIC values. Entropy is an index for assessing the precision of assigning latent class membership, with higher probability values indicating greater precisions of classification. Posterior probabilities are also obtained for each case indicating the probability of belonging to each class. The Vuong-Lo-Mendall-Rubin likelihood ratio test was also used to test for significant differences between the models. The class membership of all women in the sample was recorded and used in subsequent analyses.

Second, a 2 × 2 between-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess for differences in emotional–behavioural difficulties on the SDQ total difficulties scale for boys and girls exposed to different trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms. This was followed up with two multivariable logistic regression models to assess the relationship between trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms and children scoring in the ‘at risk’ or ‘clinical range’ for emotional–behavioural difficulties (total difficulties scores ≥14), while accounting for other maternal, child and psychosocial factors associated with children’s outcomes in the perinatal period (model 1) and concurrently at 4 years postpartum (model 2). In the first model, the depression trajectories and factors in the perinatal period that had a significant bivariate association with child outcomes were entered as predictors. In the second model, the depression trajectories and factors in both the perinatal period and concurrently at 4 years that had a significant bivariate association with child outcomes were entered as predictors.

Missing data were replaced using full information maximum likelihood in Mplus Version 7.11 for the latent class modelling [39], and multiple imputation in SPSS for variables used in the logistic regression analyses. Ten complete datasets were imputed using a multivariate normal model incorporating variables used in all analyses. The regression analyses were conducted for each dataset separately, and then combined to provide one overall set of estimates, referred to as pooled estimates.

Results

Sample characteristics

Of the 1,507 women who met baseline eligibility criteria and returned a completed baseline questionnaire, 1,102 returned the 4-year follow-up questionnaire. Selective attrition was observed, with women completing the 4-year follow-up more likely to be older, Australian born, tertiary educated, and not on a government benefit in early pregnancy or in the first year following birth. Women completing the 4-year follow-up also had significantly lower depressive scores on the EPDS in early pregnancy and at the 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups than those who failed to complete the 4 year follow-up. A further 17 cases were excluded from the analyses due to having more than 20 % missing data on the variables of interest in the present study. The final sample for the present study was 1,085, and their demographic characteristics during early pregnancy are presented in Table 1. The majority of women enroled in the study were aged between 25 and 34 years, born in Australia, tertiary educated, in paid employment, and in a couple relationship.

Descriptive statistics

The extent of missing data across all the variables of interest was generally less than 3 %. Descriptive statistics for the main outcome variables and those relevant to the assumptions of normality and linearity are presented in Table 2. Statistical and graphical measures of normality indicated that the depression scores were positively skewed at all the time points. Given the purpose of the LCA to identify distinct patterns in the data, no data transformations were conducted.

The proportion of women who reported EPDS scores ≥13 (indicative of a probable diagnosis of major depression) in pregnancy and at 3, 6, 12, 18 months and 4 years was 6.8, 6.7, 8.1, 7.7, 9.4, and 11.7 %. Of the women who indicated that they were depressed during pregnancy for 2 weeks or longer (n = 277), 15 (5.4 %) indicated that their depressive symptoms pre-dated their pregnancy. The proportion of children in the overall sample scoring in the ‘normal’, ‘at risk’ or ‘clinical’ ranges (SDQ total difficulties scores ≥14; see www.sdqinfo.com) were 87.9, 7.2, and 4.9 %, respectively. Children in the ‘at risk’ and ‘clinical’ ranges were combined for subsequent analyses, representing children reported to be experiencing a high level of emotional–behavioural difficulties by their mothers.

Trajectories of depressive symptoms across the early parenting period

Latent class models specifying 1–4 trajectories were estimated (see Table 3). The 3-class model was accepted as the final model as its fit indexes (lower L 2, BIC, AIC) were lower than the 1- and 2-class models. Furthermore, the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test indicated a significant difference between the 2- and 3-class models, suggesting that the latter gives significant improvement in model fit over the 2-class model. The 4-class model was not selected as the difference between the 3- and 4-class models was not significant.

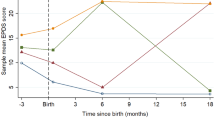

The entropy value for the 3-class model was high (.84), suggesting acceptable precision in assigning individual cases to their appropriate class. The average posterior probabilities were acceptable for Class 1 (.95), Class 2 (.89), and Class 3 (.94). Figure 1 illustrates the three trajectory classes of maternal depressive symptoms. The first and largest trajectory consisted of women who reported ‘minimal depressive symptoms’ from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum (n = 662, 61.0 %, EPDS scores ranging 2–3). The second trajectory consisted of women who reported ‘subclinical depressive symptoms’ over time (n = 328, 30.2 %, EPDS scores ranging 6–8). The smallest trajectory consisted of women who reported ‘increasing and persistently high depressive symptoms’ over time (n = 95, 8.8 %, EPDS scores ranging 10–14). It is worth noting that, on average, women assigned to this third class had scores below the clinical cut-off of 13 on the EPDS during pregnancy and at 3 months postpartum, but these increased and remained high from 6 months to 4 years postpartum.

Relationships between trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms and children’s emotional–behavioural outcomes at 4 years

The mean scores on the SDQ total difficulties scale for each trajectory by child gender are presented in Table 4. A 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVA revealed that there was no significant interaction between trajectory class and child gender, [F(2, 1,049) = 0.37, p = .690]. There were significant main effects for trajectory class, [F(2, 1,049) = 33.91, p < .001, η 2 = .06], where children of mothers in the minimal depressive symptoms trajectory were reported to have fewer emotional–behavioural difficulties than children of mothers in the Subclinical Depressive Symptoms trajectory (p < .001, Cohen’s d = .45, 95 % CI = 0.31–0.58), and increasing and persistently high symptoms trajectories (p < .001, Cohen’s d = .76, 95 % CI = 0.53–0.98). These differences were associated with moderate to large effect sizes. There were no significant differences between children of mothers assigned to the subclinical and increasing and persistently high symptoms trajectories. Significant main effects were also evident for child gender, F(1, 1,049) = 11.14, p = .001, η 2 = .01), where boys were reported to have significantly higher SDQ scores than girls. This was associated with a small effect size.

The proportion of children reported to have emotional–behavioural difficulties in the ‘at risk’ or ‘clinical’ ranges on the SDQ Total difficulties scale in the minimal depressive symptoms, the sub-clinical depressive symptoms, and increasing and persistently high symptoms trajectories was 7.0 % (46/655), 19.1 % (61/319), and 23.9 % (22/92), respectively. Given the small cell sizes, it was not possible break down by child gender.

Bivariate associations between the trajectories of depressive symptoms and children’s emotional–behavioural difficulties on the ‘at risk’ or ‘clinical’ ranges were estimated (see Table 5). Children of mothers assigned to the subclinical and increasing and persistently high symptom trajectories were more likely to have difficulties in the ‘at risk’ or ‘clinical’ range compared with children of mothers assigned to the minimal depressive symptoms trajectory. Bivariate associations between children’s emotional–behavioural outcomes and other maternal, child, and psychosocial characteristics in the perinatal period and at 4 years postpartum are also presented in Table 5.

The first multivariable model examined the association between the trajectories of depressive symptoms and children’s emotional–behavioural difficulties whilst accounting for salient demographic and perinatal factors (maternal, child, and psychosocial). In this model, children of mothers assigned to the subclinical and increasing and persistently high depressive symptoms trajectories were more likely to have difficulties in the ‘at risk and ‘clinical’ range compared to children of mothers assigned to the minimal depressive symptoms trajectory, after adjusting for demographic and perinatal factors. Other factors associated with emotional–behavioural difficulties were lower maternal age, high school as highest educational attainment, and low emotional satisfaction in the couple relationship.

The second multivariable model also accounted for salient characteristics concurrently when the children were aged 4 years. A similar pattern of results were obtained, where children of mothers assigned to the subclinical and increasing and persistently high depressive symptoms trajectories were more likely to have difficulties in the ‘at risk’ or ‘clinical’ range compared with children of mothers assigned to the minimal depressive symptoms trajectory, even after adjusting for characteristics in the perinatal period (model 1) and concurrently at 4 years postpartum (model 2). Other factors associated with emotional–behavioural difficulties were younger maternal age, high school as highest educational attainment, lower maternal involvement in home learning activities at 4 years postpartum, as well as low emotional satisfaction in the couple relationship and limited partner contribution to caring for the child at 4 years postpartum.

Discussion

Drawing upon rich longitudinal data from a birth cohort of over 1,000 Australian women and their children, the present study examined associations between the severity and chronicity of maternal perinatal mental health problems and pre-school children’s emotional–behavioural functioning. First, we identified three distinct trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms from pregnancy to 4 years postpartum. The majority of women were assigned to a group characterized by very few symptoms across the early childhood period (61 %), whilst approximately one-third of women exhibited a pattern of persistent depressive symptoms that remained at a subclinical level across time (30 %). The smallest group consisted of women who had an increasing and persistent pattern of high depressive symptoms over time (9 %). On average, these women had scores below the clinical cut-off of 13 on the EPDS during pregnancy, but by 6 months postpartum their scores were above the clinical cut-off and continued to remain high across time. It is likely that some of these women may have experienced mental health difficulties prior to pregnancy, and that over time their symptoms worsened as they made the transition to parenthood and experienced the demands of early caregiving.

Notably, our findings indicate that approximately 40 % of children in the study were living with mothers experiencing some level of mood disturbance such as depressed mood, crying, and feeling worried or anxious across the perinatal and early childhood period. The proportion of children experiencing emotional–behavioural difficulties in the ‘at risk’ or ‘clinical’ range on the SDQ was highest for children whose mothers had an ‘increasing and persistent’ pattern of depressive symptoms (24 %), followed by ‘subclinical’ symptoms (19 %) and ‘minimal’ symptoms (7 %). Whilst these findings are consistent with previous studies reporting poor outcomes for children of prenatally and postnatally depressed mothers [4, 22], notably, our findings demonstrated no significant differences in functioning for children exposed to ‘subclinical symptoms’ and ‘increasing and persistent’ symptoms. Both groups of children were at least two times more likely to experience emotional–behavioural difficulties than children of mothers with no or minimal symptoms, even after accounting for other perinatal and concurrent factors associated with children’s outcomes. These findings suggest that children exposed to persistent depressive symptoms even at low levels are at increased risk of emotional and behavioural difficulties. It is important to note that these children would not have been identified if we only considered women’s scores at the commonly used clinical cut-offs of 10 or 13 on the EPDS. This raises questions for research studies and current models of care that tend to rely on clinical cut-offs to identify women with symptoms requiring intervention or follow-up.

Importantly, we explored the relationships between maternal depression trajectories and children’s outcomes whilst accounting for a range of other demographic, child, and psychosocial characteristics in the perinatal period and concurrently at 4 years. Although still significant, we found that the relationships between depression trajectories and children’s outcomes were attenuated when accounting for perinatal and concurrent factors. Younger maternal age, low maternal education, low satisfaction in the couple relationship in the early postnatal period and at 4 years postpartum, and limited partner contribution to caring for the child at 4 years were also associated with poorer emotional–behavioural outcomes for children. It is likely that these characteristics are social determinants of mental health for both mothers and children, and key pathways by which maternal mental health difficulties contribute to children’s emotional–behavioural difficulties. For instance, the couple relationship is an important source of both emotional and practical support. However, if mothers are not satisfied in the relationship or they perceive little support from their partner in caregiving, this may contribute to their depressive symptoms. Whilst depressive symptoms may also influence mothers’ perceptions of the couple relationships and the support they receive, an early caregiving environment characterized by poor quality couple relationships is also likely to have a negative impact on children’s emotional–behavioural functioning.

Another interesting finding was that the risk of emotional–behavioural difficulties was slightly higher for children whose mothers had ‘sub-clinical’ levels of depression than those with ‘persistent and increasing’ symptoms in the adjusted models. This finding might be best explained by considering research indicating that women experiencing persistent and more severe postnatal depressive symptoms are more likely to experience couple relationship difficulties, lack of social support and social isolation, and past history of mental health difficulties than women experiencing fewer depressive symptoms [5]. Given that their children are also more likely to experience these life circumstances, our particular findings may reflect the complex relationships among their variables of interest, where exposure to a broader range of risk factors may partial out some effects of maternal depression on children children’s outcomes.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that the majority of children whose mothers reported depressive symptoms across the early childhood period were reported to have optimal emotional–behavioural functioning in the normal range on the SDQ. These findings may be explained by drawing on theoretical perspectives such as the ‘differential susceptibility hypothesis’ [40] which posits that children can vary markedly in their biological sensitivity to their caregiving and social environments, whereby some children may be more vulnerable to the negative effects of adversity than others [40, 41]. Similarly, some children may be disproportionately responsive to the beneficial effects of positive, supportive caregiving, and social environments compared to others [40]. To date, only a few studies have explored the factors associated with resilient outcomes for children exposed to maternal depression, finding that high levels of maternal warmth, low levels of maternal over-involvement and parental control were associated with resilient outcomes (i.e., [42, 24] ). Our findings also suggest that maternal involvement in home learning activities such as reading from a book and involving children in everyday activities, might be a protective factor worth further investigation. This would help to understand how mothers experiencing depression and other forms of social adversity can be supported to provide an enriching home early environment that will maximize opportunities for their children’s optimal health and development.

Strengths, limitations and future directions

This study benefits from using sophisticated longitudinal statistical modelling of data drawn from a prospective pregnancy cohort following over 1,000 women’s health and wellbeing across the formative years of their children’s lives. However, there are several limitations to note. First, this study relied on data from women who reported on both their mental health symptoms and children’s emotional–behavioural functioning. Negative self-report bias may have influenced the strength of the associations, where depressed mothers may have rated their children’s emotional and behavioural functioning more negatively than mothers who were not depressed. Some multiple informant and/or independent observations or measures would add weight to our findings. Second, children’s emotional–behavioural functioning was assessed at one time point in early childhood. Examining trajectories of children’s emotional–behavioural functioning alongside changes in maternal mental health over time is needed to obtain a better understanding of the complex and bi-directional associations between maternal and child mental health.

Third, some measures used were necessarily brief and purpose-designed for the study, which may have led to an underestimation of the strength of the relationships such as couple relationship functioning, partner involvement in caregiving, and children’s outcomes. Furthermore, some key potential covariates associated with children’s outcomes such as parenting behaviour and partner mental health were not included in the study. We also had limited information about women’s mental health prior to pregnancy. Of the women who reported depressive symptoms for 2 weeks or longer during pregnancy (n = 277), approximately 5 % indicated that their symptoms predated their pregnancy. The emotional–behavioural difficulties for children with mothers who have a past history of preconception mental health difficulties might be more severe than for children of mothers experiencing new onset of depressive symptoms, but the retrospective report of past mental health difficulties and the small number of women reporting pre-conception mental health difficulties precluded meaningful analyses in this study.

Finally, women and children from some vulnerable backgrounds (i.e., non-English speaking, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, low socioeconomic) were under represented in the study, limiting generalizability of the study findings to these groups. Women who were not in a couple relationship were also underrepresented in the study at approximately 5 %. We chose to retain these women in the analyses, and although not ideal we coded their relationship quality as low. We are also aware that women lost to follow-up at 4 years postpartum reported higher depressive symptoms during pregnancy and in the first postnatal year than women retained in the study. In addition to limits to generalizability, this may have led to an underestimation of the strength of the relationships between maternal mental health and children’s emotional–behavioural outcomes.

Policy and practice implications

The findings of the present study have important implications for policy and practice efforts focused on improving maternal and child health in the perinatal and early childhood period. In a climate of fiscal constraint, health services often prioritize the provision of services to children and families experiencing more extreme levels of stress or social adversity. Current models of maternal and child health care focus on the early identification, referral and follow-up of women who report mental health difficulties at a clinical cut-off on established measures such as the EPDS in the early postnatal period. Yet, this study reveals that a substantial proportion of women (40 %) experience depressive symptoms across the perinatal and early childhood period that would not be detected if clinicians relied on clinical cut-offs. Our findings indicate that even sub-clinical levels of depressive symptoms are associated with adverse emotional–behavioural outcomes for children. This suggests that policy makers and health professionals cannot afford to be complacent about the impact of parent mental health and associated life stress for families at this stage (i.e., couple relationship difficulties, lack of social support, financial difficulties) that may contribute to children’s mental health difficulties. It does, however, challenge primary care and maternal-child health services to consider how they can provide early identification and intervention services to women experiencing mild to moderate depressive symptoms as well as clinically significant symptoms, not only in the early postnatal period, but well into the preschool years. Tailoring care and support to match needs across a broader spectrum of symptoms across the early childhood period may break persisting patterns of depressive symptoms, maximizing opportunities to improve both short-and long-term maternal and child health outcomes.

References

Schlotz W, Phillips D (2009) Fetal origins of mental health: evidence and mechansims. Brain Behav Immun 23(7):905–916

Downey G, Coyne J (1990) Children of depressed parents: an integrative review. Psychol Bull 108:50–76

Gelfand D, Teti D (1990) The effects of maternal depression on children. Clin Psychol Rev 10(3):329–353

Kingston D, Tough S, Whitfield H (2012) Prenatal and postpartum maternal psychological distress and infant development: a systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 43:683–714

Giallo R, Cooklin A, Nicholson J (2014) Risk factors associated with trajectories of mothers’ depressive symptoms across the early parenting period: an Australian-based longitudinal study. Arch Womens Ment Health 17:115–125

Woolhouse H, Gartland D, Mensah F, Brown S (2014) Maternal depression from early pregnancy to 4 years postpartum in a prospective pregnancy cohort study: implications for primary health care. BJOG. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.12837

Priest S, Austin M-P, Barnett B, Buist A (2008) A psychosocial risk assessment model (PRAM) for use with pregnant and postpartum women in primary care settings. Arch Womens Ment Health 11:307–317

Brown S, Lumley J (1998) Changing childbirth: lessons from an Australian survey of 1336 women. BJOG 105:143–155

Gavin N, Gaynes B, Lohr K, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T (2005) Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gyn 106:1071–1083

O’Hara M, Swain A (1996) Rates and risk of postpartum depression: a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry 8(1):37–54

Horowitz J, Damato E, Solon L, von Metzsch G (1996) Identification of symptoms of postpartum depression: linking researh to practice. J Perinatol 16(5):360–365

Affonso D, Lovett S, Paul S, Sheptak S, Nussbaum R, Newman L, Johnson B (1992) Dysphoric distress in childbearing women. J Perinatol 12(4):325–332

Matthey S, Barnett B, Ungerer J, Waters B (2000) Paternal and maternal depressed mood during the transition to parenthood. J Affect Disord 60:75–85

Beeghly M, Weinberg M, Olson K, Kernan H, Riley J, Tronick E (2002) Stability and change in level of maternal depressive symptomatology during the first postpartum year. J Affect Disord 71:169–180

McCue Horwitz S, Briggs-Gowan M, Storfer-Isser A, Carter A (2007) Prevalence, correlates, and persistence of maternal depression. J Womens Health 16(5):678–691

McLennan J, Kotelchuck M, Cho H (2001) Prevalence, persistence, and correlates of depressive symptoms in a national sample of mothers of toddlers. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 40(11):1316–1323

Small R, Brown S, Lumley J, Astbury J (1994) Missing voices: what women say and do about depression after childbirth. J Reprod Infant Psychol 12(2):89–103

Cents R, Diamantopoulou S, Hudziak J, Jaddoe V, Hofman F, Verhulst M, Lambregtse-van den Berg M, Tiemeier H (2013) Trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms predict child problem behaviour: the generation R study. Psychol Med 43:13–25

Muthen B (2002) Beyond SEM: general latent variable modeling. Behaviormetrika 29:81–117

Nagin D, Tremblay R (2001) Analyzing developmental trajectories of distinct but related behaviours: a group-based method. Psychol Methods 6:18–34

Mora P, Bennett I, Elo I, Mathew L, Coyne J, Culhane J (2009) Distinct trajectories of perinatal depressive symptomatology: evidence from growth mixture modelling. Am J Epidemiol 169:24–32

Kingston D, Tough S (2013) Prenatal and postnatal maternal mental health and school-age child development: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J (early view)

Brennan P, Hammen C, Andersen M, Bor W, Najman J, Williams G (2000) Chronicity, severity, and timing of maternal depressive symptoms: relationships with child outcomes at age 5. Dev Psychol 36(6):759–766

Early Child Care Research Network (1999) Chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and child functioning at 36 months. Dev Psychol 35:1297–1310

Campbell S, Matestic P, von Stauffenberg C, Mohan R, Kirchner T (2007) Trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and children’s functioning at school entry. Dev Psychol 43:1202–1215

Campbell S, Morgan-Lopez A, Cox M, McLoyd V (2009) A latent class analysis of maternal depressive symptoms over 12 years and offspring adjustment in adolescence. J Abnorm Psychol 118:479–493

Grant K, Compas B, Sthulmacher A, Thurm A, McMahon S, Halpert J (2003) Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: moving form markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychol Bull 129:447–466

Gerard J, Krishnakumar A, Buehler C (2006) Marital conflict, parent-child relations, and youth maladjustment. J Fam Issues 27:951–975

Wake M, Sanson A, Berthelsen D, Hardy P, Mission P, Smith K, Ungerer J, The LSAC Research Consortium (2008) How well are Australian infants and children aged 4–5 years doing? Findings from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Wave 1

Sarkadi A, Kristiansson R, Oberklaid F, Bremberg S (2008) Fathers’ involvement and children’s developmental outcomes: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatr 97:153–158

Brown S, Lumley J, McDonald E, Krastev A (2006) Maternal health study: a prospective cohort study of nulliparous women recruited in early pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 1:12

Cox J, Holden J, Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry 150:782–786

Murray D, Cox J (1990) Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh depression scale (EDDS). J Reprod Infant Psychol 8(2):99–107

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:581–586

Goodman R (2001) Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties (SDQ). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40:1337–1345

Hawes D, Dadds M (2004) Australian data and psychometric properties of the Strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 38:644–651

Colley Gilbert B, Shulman H, Fischer L, Rogers M (1999) The pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS): methods and 1996 response rates from 11 states. Matern Child Health J 3:199–209

Sanson A, Nicholson J, Ungerer J, Zubrick S, Wilson K, Ainley J, Berthelsen D, Bittman M, Broom D, Harrison L, Rodgers B, Sawyer M, Silburn S, Strazdins L (2002) Introducing the longitudinal study of Australian children. Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne

Muthen L, Muthen B (1998–2013) Mplus User’s Guide. Muthen and Muthen, Los Angeles

Belsky J, Pluess M (2009) Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychol Bull 2009:885–908

Boyce W, Ellis B (2005) Biological sensitivity to context: an evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Dev Psychopathol 17:271–301

Brennan P, Le Brocque R, Hammen C (2003) Maternal depression, parent-child relationships, and resilient outcomes in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42:1469–1477

Acknowledgments

This study was approved by the following human research ethics committees: La Trobe University (2002/38); Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne (2002/23); Southern Health, Melbourne (2002-099B; Angliss Hospital, Melbourne (2002), Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne (27056A). This research was supported by project grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (numbers ID191222, ID433006 and ID1048829), a VicHealth Public Health Research Fellowship (2002-2006), a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Award (ID491205) and ARC Future Fellowship (IDFT110101036) awarded to S.J.B, and the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program. We are extremely grateful to the women taking part in the study; to members of the Maternal Health Study Collaborative Group; and to members of the Maternal Health Study research team who have contributed to data collection and coding.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giallo, R., Woolhouse, H., Gartland, D. et al. The emotional–behavioural functioning of children exposed to maternal depressive symptoms across pregnancy and early childhood: a prospective Australian pregnancy cohort study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24, 1233–1244 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0672-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0672-2