Abstract

Background

To date, the therapy of intralabyrinthine schwannoma consists mainly of a wait-and-see approach, completely ignoring auditory rehabilitation. Only a few single-case reports are as yet available on treatment with cochlear implants (CI).

Aim of the study

This study aimed to assess the results of auditory rehabilitation after treatment with CI in a series of cases.

Materials and methods

The demographic findings, symptoms, and results of surgical therapy in 8 patients were evaluated in a retrospective analysis.

Results

Prior to surgery, all patients presented with profound hearing loss and tinnitus. Episodic dizziness was reported by 3 patients. Among the patients, 4 had an intracochlear and 3 an intravestibular schwannoma, and a transmodiolar schwannoma was found in 1 patient. A total of 6 patients underwent treatment with CI. The results of auditory rehabilitation are favorable with open-set speech comprehension.

Conclusion

CI treatment following resection of an intralabyrinthine schwannoma is a promising option for auditory rehabilitation, even in single-sided deafness. This is a new treatment concept in contrast to the wait-and-scan policy. Expectant management appears justified only if the patient still has usable hearing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Intralabyrinthine schwannomas are rare, benign tumors which account for about 10 % of all schwannomas [19]. They are typically diagnosed at a mean age of about 50 years [22]. About 50 % of the intralabyrinthine schwannomas occur purely intracochlear [22]. Modern nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) enables the identification of even small tumors, which can be classified by the methods described by Kennedy et al. [11] and van Abel et al. [22] as follows:

In addition to purely intravestibular and intracochlear tumors, the location can also be intracochlear and intravestibular at the same time. When there is expansion into the internal auditory canal arising from the cochlea, transmodiolar growth can be assumed. Arising from the vestibulum, progression of tumor growth into the internal auditory canal as a transmacular tumor is also possible. Progression of tumor growth may involve the entire inner ear and the internal auditory canal, as well as expansion of the tumor into the middle ear or the cerebellopontine angle [22].

The typical symptoms of these tumors include hearing loss, sometimes fluctuating, tinnitus and dizziness. Hearing loss, as described by van Abel et al. [22], was found in 99 % of the patients (n = 262); profound hearing loss was found in 87 % of the patients. Dizziness, usually episodic, existed in 59 % and tinnitus in 76 % of the patients. Dizziness was significantly associated with a tumor location in the vestibular labyrinth.

Therapy of choice thus far has been a wait-and-scan policy, especially when usable hearing was still present [4, 17, 22]. The indication for surgery was not given until tumor growth progressed to the internal auditory canal, or there was dizziness which could not be treated conservatively.

The auditory rehabilitation of these patients always took second place. There are only a few single case reports of cochlear implant (CI) treatment [12, 13, 18, 21]. Usually there was bilateral deafness or at best asymmetric hearing ability, or it was an intraoperative chance finding.

Increasing acceptance and the success of CI treatment in single-sided deafness of various etiologies, especially following resection of vestibular schwannomas [1, 2, 6–8, 16] should lead to a reevaluation of the therapeutic possibilities for this tumor entity.

Materials and methods

The authors performed a retrospective study of the anamnesis, diagnosis, and therapy, including the results of auditory rehabilitation in patients with intralabyrinthine schwannoma, who were treated in the authors’ hospital between 2011 and 2015.

Results

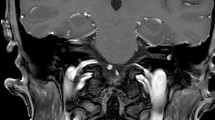

In all, 8 patients between 47 and 55 years of age presented in our hospital with intralabyrinthine tumors (Table 1). There was a history of hearing loss (duration 0.3–20 years) and tinnitus in all patients. Only 3 patients reported episodic dizziness (Table 2). At least profound hearing loss could be preoperatively demonstrated on the tumor side in all patients; hearing was normal on the contralateral side in 6 patients and 2 patients had asymmetric hearing loss. One patient became symptomatic with deafness which was a chance finding in otitis media. The MRI examination raised suspicion of a beginning obliteration (Fig. 1). The diagnosis of schwannoma was initially made intraoperatively and was confirmed, as in all the other patients, histologically.

Intracochlear schwannoma in the first half of the basal turn in the MRI, axial (a, d), coronary (b, e), and oblique (c, f) reconstruction; a–c in the CISS sequence reduction of the fluid signal (arrows) and d–f corresponding pathological contrast medium enhancement (arrows) in the T1-sequence with gadolinium

After extensive consultation and presentation of the therapeutic options: expectant management with repetitive MRI scans, resection, radiation therapy, and testing of hearing rehabilitation by means of CROS/BiCros hearing aids (contralateral routing of signals) or BAHS-CROS (bone-anchored hearing systems), all patients decided to undergo a surgical procedure. Prior to treatment, the authors discussed all patients in an interdisciplinary skull-base conference.

Schwannoma resection was performed intracochlear (n = 4, Fig. 2) and intravestibular (n = 3, Fig. 3) and there was one transmodiolar schwannoma (Fig. 4). For the tumor resection approach, the authors selected either a partial (vestibular) labyrinthectomy (n = 3, Fig. 5), an expanded cochleostomy of the basal turn (n = 4) (Fig. 6), an additional cochleostomy of the second turn (n = 3) (Fig. 7), or in one case additional opening of the internal auditory canal (Table 2). The postoperative course was uneventful in 7 patients; one patient (patient 8) reported postoperative vertigo which resolved completely with physical therapy.

In 6 cases, CI were used for auditory rehabilitation, in 2 of these patients sequentially after control MRI and promontory test after 13 and 19 months, respectively. To prevent obliteration or ossification of the cochlea, these patients had an intracochlear placeholder after they had been informed concerning the off-label use. The authors treated 4 patients simultaneously with a CI. One patient did not wish for further therapy, not even a hearing aid. One patient with transmodiolar tumor and clinically preserved hearing nerve had a negative promontory test and decided on a CROS hearing aid.

Intracochlear schwannoma of the entire basal turn in the MRI. The CISS sequence (a, b) shows a reduced fluid signal basal (a, arrow) and normal fluid signal in the second turn (b, arrow). Corresponding pathological contrast medium enhancement (c, arrow) of the basal turn in the oblique reconstruction in the T1-sequence with gadolinium. The postoperative rotation tomography (d–f) shows the insertion of the electrode via a regular cochleostomy (d, arrow) and the second cochleostomy (e, arrow) to open the second turn, and the correct intracochlear electrode position (f)

a Extended cochleostomy with schwannoma in the Scala tympani and Scala vestibuli, (arrow Osseous spiral lamina); b intraoperative situation after extension of the posterior tympanotomy and resection of the incus (PC Cochleariforme process, arrow head of the stapes), c Opening of the second turn (arrow) inferior to cochleariforme process, d after tumor resection and insertion of the electrode array, the tip of the electrode is now seen in the second cochleostomy (arrow)

Of the 6 patients who underwent CI, 5 have already adjusted to the system and have 3–39 months of CI experience. All patients use their CI for the whole day, achieve open-set speech comprehension (Fig. 8) and also profit subjectively from the CI treatment [8]. The patients with early or simultaneous treatment appear to have more favorable outcomes.

Discussion

In this case series, the authors present 8 patients with primary intralabyrinthine schwannomas. The mean age at diagnosis was 50 years, which corresponds to the available literature [22]. Three patients presented with intravestibular tumors, 4 patients purely intracochlear tumors, and 1 patient had transmodiolar growth. The CI surgery was performed in 6 patients either sequentially or simultaneously. One woman refused further surgery and hearing rehabilitation with CROS/BAHS hearing aids. Despite intraoperatively preserved auditory nerve, the promontory test of the patient with transmodiolar growth was negative and consecutive therapy consisted of a CROS hearing aid.

All patients presented with profound hearing loss or deafness, 4 patients reported episodic dizziness and all patients complained of tinnitus. The symptom combination may give an impression similar to Menière disease [10], whereby, however, progression to deafness, in contrast to low-frequency hearing loss, may be an indication of intralabyrinthine schwannoma. The caloric examinations in the present case series were pathological in all 3 intravestibular tumors. Schutt and Kveton [18] reported pathological vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMP) in normal caloric testing in their case report. In the future, performance of the VEMP in addition to caloric testing should enable more precise differentiation.

Previous approach

In the available literature, wait and scan is initially recommended when this tumor entity is diagnosed. A wait-and-scan policy with repetitive MRIs should serve as the basis for further treatment options. According to Tielemann et al. [19], the growth behavior is progressive in 59 % of the patients and a course up to 16 years. In 2012, Saltzmann et al. [17] reported, however, on growth in only about 15 % of the patients over a follow-up period of about 5 years.

Focus on tumor control

Especially the fact that all surgical procedures unavoidably lead to deafness contributed in the past to this wait-and-scan management. By contrast, van Abel et al. [22] reported a frequency of hearing loss in 99 % of the patients and profound hearing loss in at least 87 % of the patients, so that Schutt and Kveton [17] assume that a majority of patients with intralabyrinthine schwannomas are already CI candidates at presentation. Stereotactic radiosurgery [22] can be offered but is assessed with reservation due to the risk of side effects (deafness, damage to the facial nerve) and unclear tumor control in only slight growth tendency and small tumor volumes [11, 15].

In summary, however, it must be noted that the treatment focus in the past was always on tumor control and auditory rehabilitation was not a therapy goal.

Future approach

Thanks to increased acceptance and the very positive results of CI treatment in single-sided deafness [1, 2, 6, 7], even after vestibular schwannoma surgery [8, 16], the present results could provide the basis for a new management strategy in the treatment of intralabyrinthine schwannomas; the current literature already refers to this management as a paradigm shift [18].

Focus on auditory rehabilitation

The positive results of auditory rehabilitation in our patients show that, from our point of view, it is justified to place the focus on auditory rehabilitation. As an alternative to CI operation, if surgery is not desired or not possible, treatment with CROS/Bi-CROS hearing aids or BAHS-CROS can be offered. However, the studies available in patients with single-sided deafness (SSD) [1, 8] show superiority of the CI treatment. Recovery of spatial hearing as a binaural achievement is only possible with a CI. CROS/Bi-CROS or BAHS-CROS offer advantages in only one situation (speech is presented to the deaf ear and noise to the hearing ear) [1].

Limitations

The still small number of cases and the lack of long-term results in these patients are a weakness of the present study.

Alternative treatments

As an alternative to simultaneous CI operation, a primary tumor resection and positioning of a placeholder can be performed. This is necessary, since obliteration of the cochlea only 3 months after a translabyrinthine surgery is possible, and in the long run, this would prevent CI treatment. One year after translabyrinthine surgery [3, 5] there were intralabyrinthine changes in 32–66 % of the patients examined. An unchanged labyrinth, which would allow CI treatment, was only found in 11 % of the patients. For this reason, Beutner et al. [3] recommend simultaneous or early CI treatment, or positioning of a placeholder. In current state-of-the-art, this is possible using a “depth-gauge” which is available from various manufacturers [5]. Positioning as a spacer is, however, an off-label use and requires appropriate instruction of the patient. This procedure would enable MRI controls, as is customary in follow-up of vestibular schwannomas. Radiological assessment of recurrences would be greatly hindered or nearly impossible because of artefacts caused by CI treatment. An improved positioning of the receiver/stimulator, as suggested by Todt et al. in 2015 [20], would enable MRI evaluation. This should be respected in the surgical planning.

In addition, an optimized MRI protocol can be helpful to depict the inner region to be controlled [23]. Following of these suggestions is recommended as at least in intracochlear tumors a complete removal cannot be guaranteed, and the place of origin is still unclear. Based on the very slow growth tendency, which makes the appearance of recurrences requiring treatment extremely unlikely following resection [19], CI treatment still seems to be possible nonetheless.

Future

Even though few long-term results are available for the patients presented in this article [8], the patients with simultaneous CI treatment show a tendency to more favorable rehabilitation results. The speech comprehension is comparable to that of other patients with single-sided deafness of different etiologies [9]. The development of speech comprehension seems to point at quicker and better results in comparison to other adults with bilateral deafness [14].

The intracochlear resection of schwannomas, either via an expanded cochleostomy or even an opening of the second turn, leads to considerable traumatization of intracochlear structures, including resection of the osseous spiral lamina. Consecutively, neurodegeneration at the level of the spiral ganglion must be anticipated. So at least in intracochlear tumors, immediate CI treatment and very early electrical stimulation appears important to achieve the most favorable rehabilitation results possible [18] as indicated in the patient group presented in this article. Wait and scan only appears justified in the case of useable hearing.

Practical conclusion

-

Auditory rehabilitation after resection of intralabyrinthine schwannomas by means of CI is successful.

-

Compared to the current wait-and-scan policy, it represents a new therapeutic management.

-

The results are promising; further studies, especially of the long-term course, are necessary.

References

Arndt S, Laszig R, Aschendorff A, Beck R, Schild C, Hassepass F, Ihorst G, Kroeger S, Kirchem P, Wesarg T (2011) Einseitige Taubheit und Cochlear-implant-Versorgung – Audiologische Diagnostik und Ergebnisse. HNO 59:437–446

Arndt S, Aschendorff A, Laszig R, Beck R, Schild C, Kroeger S, Ihorst G, Wesarg T (2011) Comparison of pseudobinaural hearing to real binaural hearing rehabilitation after cochlear implantation in patients with unilateral deafness and tinnitus. Otol Neurotol 32:39–47

Beutner C, Mathys C, Turowski B, Schipper J, Klenzner T (2015) Cochlear obliteration after translabyrinthine vestibular schwannoma surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 272:829–833

Bouchetemblé P, Heathcote K, Marie JP (2015) Intralabyrinthine schwannomas: a case series with discussion of the diagnosis and management. Otol Neurotol 36:64–65

Charlett SD, Biggs N (2015) The prevalence of cochlear obliteration after labyrinthectomy using magnetic resonance imaging and the implications for cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol 36:1328–1330

Firszt JB, Holden LK, Reeder RM, Waltzman SB, Arndt S (2012) Auditory abilities after cochlear implantation in adults with unilateral deafness: a pilot study. Otol Neurotol 33:1339–1346

Hassepass F, Schild C, Aschendorff A, Laszig R, Maier W, Beck R, Wesarg T, Arndt S (2013) Clinical outcome after cochlear implantation in patients with unilateral hearing loss due to labyrinthitis ossificans. Otol Neurotol 34:1278–1283

Hassepass F, Arndt S, Aschendorff A, Laszig R, Wesarg T (2015) Cochlear implantation for hearing rehabilitation in single-sided deafness after translabyrinthine vestibular schwannoma surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. doi:10.1007/s00405-015-3801-8

Jacob R, Stelzig Y, Nopp P, Schleich P (2011) Audiologische Ergebnisse mit Cochleaimplantat bei einseitiger Taubheit. HNO, vol. 59., pp 453–460

Just T, Hingst V, Pau HW (2010) Intracochleäres Schwannom: Eine Differenzialdiagnose bei menièriformen Beschwerden. Laryngorhinootologie 89:368–370

Kennedy RJ, Shelton C, Salzman KL, Davidson HC, Harnsberger HR (2004) Intralabyrinthine schwannomas: diagnosis, management, and a new classification system. Otol Neurotol 25:160–167

Kim YH, Jun BC, Yun SH, Chang KH (2013) Intracochlear schwannoma extending to vestibule. Auris Nasus Larynx 40:497–499

Kronenberg J, Horowitz Z, Hildesheimer M (1999) Intracochlear schwannoma and cochlear implantation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 108:659–660

Lenarz M, Sönmez H, Joseph G, Büchner A, Lenarz T (2012) Cochlear Implant performance in geriatric patients. Laryngoscope 122:1361–1365

Neff BA, Willcox TO, Sataloff RT (2003) Intralabyrinthine Schwannomas. Otol Neurotol 24:299–307

Pai I, Dhar V, Kelleher C, Nunn T, Connor S, Jiang D, O’Connor AF (2013) Cochlear implantation in patients with vestibular schwannoma: a single United Kingdom center experience. Laryngoscope 123:2019–2023

Salzman KL, Childs AM, Davidson HC, Kennedy RJ, Shelton C, Harnsberger HR (2012) Intralabyrinthine schwannomas: imaging diagnosis and classification. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 33:104–109

Schutt CA, Kveton JF (2014) Cochlear implantation after resection of an intralabyrinthine schwannoma. Am J Otolaryngol 35:257–260

Tieleman A, Casselman JW, Somers T, Delanote J, Kuhweide R, Ghekiere J, De Foer B, Offeciers EF (2008) Imaging of intralabyrinthine schwannomas: a retrospective study of 52 cases with emphasis on lesion growth. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 29:898–905

Todt I, Rademacher G, Mittmann P, Wagner J, Mutze S, Ernst A (2015) MRI artifacts and Cochlear Implant positioning at 3 T in vivo. Otol Neurotol 36:972–976

Tono T, Ushisako Y, Morimitsu T (1997) Cochlear implantation in an intralabyrinthine acoustic neuroma patient after resection of an intracanalicular tumor. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 52:155–157

Van Abel KM, Carlson ML, Link MJ, Neff BA, Beatty CW, Lohse CM, Eckel LJ, Lane JI, Driscoll CL (2013) Primary inner ear schwannomas: a case series and systematic review of the literature. Laryngoscope 123:1957–1966

Walton J, Donelly NP, Tam YC, Joubert I, urie-Grair J, Jackson C, Mannion RA, Tysome JR, Axon PR, Scoffings DJ (2014) MRI without magnet removal in Neurofibromatosis type 2 patients with cochlear and auditory brainstem implants. Otol Neurotol 35:821–825

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

A. Aschendorff, S. Arndt, R. Laszig, T. Wesarg, F. Hassepaß and R. Beck state that they receive support for research projects from all CI manufacturers.

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

The supplement containing this article is not sponsored by industry.

Additional information

Redaktion

W. Baumgartner, Wien

P. K. Plinkert, Heidelberg

M. Ptok, Hannover

C. Sittel, Stuttgart

N. Stasche, Kaiserslautern

B. Wollenberg, Lübeck

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aschendorff, A., Arndt, S., Laszig, R. et al. Treatment and auditory rehabilitation of intralabyrinthine schwannoma by means of cochlear implants. HNO 65 (Suppl 1), 46–51 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00106-016-0217-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00106-016-0217-8