Abstract

Background

Global trend has seen management shift towards selective conservatism in penetrating abdominal trauma (PAT). The purpose of this study is to compare the presentation; management; and outcomes of patients with PAT managed operatively versus non-operatively.

Methods

Prospective cohort study of all patients Ùpresenting with PAT to Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town from 01 May 2015 to 30 April 2017. Presentation; management; and outcomes of patients were compared. Univariate predictors of delayed operative management (DOM) were explored.

Results

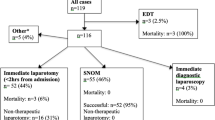

Over the 2-year study period, 805 patients with PAT were managed. There were 502 (62.4%); and 303 (37.6%) patients with gunshot (GSW) and stab wounds (SW), respectively. The majority were young men (94.7%), with a mean age of 28.3 years (95% CI 27.7–28.9) and median ISS of 13 (IQR 9–22). Successful non-operative management was achieved in 304 (37.7%) patients, and 501 (62.5%) were managed operatively. Of the operative cases, 477 (59.3%) underwent immediate laparotomy and 24 (3.0%) DOM. On univariate analysis, number; location; and mechanism of injuries were not associated with DOM. Rates of therapeutic laparotomy were achieved in 90.3% in the immediate, and 80.3% in the DOM cohorts. The mortality rate was 1.3, 11.3 and 0% in the in the NOM, immediate laparotomy and DOM subgroups, respectively. The rate of complications was no different in the immediate and DOM cohorts (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

Patients with PAT in the absence of haemodynamic instability; peritonism; organ evisceration; positive radiological findings, or an unreliable clinical examination, can be managed expectantly without increased morbidity or mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Penetrating abdominal trauma (PAT) in South Africa is amongst the most prevalent worldwide. In 2013, interpersonal violence was ranked 5th in all-cause mortality in Cape Town [1]. Groote Schuur Hospital (GSH) is a government-funded, tertiary teaching hospital situated in Cape Town, South Africa. It is the chief academic hospital of the University of Cape Town and one of the busiest trauma referral hospitals in the world, with an estimated 10,000 patients being seen in the trauma unit annually, 70% having sustained intentional injuries of which 57% is of a penetrating mechanism. The current global trend in PAT has seen management shift towards selective conservatism [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. The purpose of this study is to compare the presentation, management and outcomes of patients managed non-operatively versus operatively (both immediate and delayed) in our unit to provide evidence-based guidance for the safe implementation of selective conservatism in PAT.

Methods

Setting and data sources

GSH is the central referral hospital in the Cape Metro West health district, which serves an estimated catchment area of 2,292,000 uninsured patients. It has 975 beds of which 50 beds are dedicated to trauma. The validated, electronic Trauma Health Record (eTHR) was implemented at GSH in January 2014, whereby electronically generated records replaced all previous handwritten record keeping [10]. Data variables required by eTHR are collected prospectively by clinicians in real time including data required by the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) classification system—a consensus-derived, anatomically based, 7-digit injury scoring system used to generate the ISS [11, 12].

Patients presenting to the centre with PAT during the study period of 2 years between 1 May 2015 and 30 April 2017, were identified from eTHR and prospectively entered into a REDCap database designed to specifically audit the outcomes of patients with PAT [13]. Penetrating abdominal trauma was defined as any penetrating wound between the 5th intercostal space and the pubis anteriorly, and the angle of the scapula down to the creases of the buttock posteriorly. The abdomen was further subdivided into the following zones (with borders) for descriptive purposes: thoracoabdominal (from the 5th intercostal space to the costal margin); anterior abdomen (from the xiphoid to pubis, between the anterior axillary lines); pelvis (iliac crests superiorly down to the perineum inferiorly); and back/flank (posterior to the anterior axillary lines). The management pathway, i.e. immediate laparotomy or non-operative management (NOM), as well as the need for additional imaging, was determined by the trauma surgical trainee following adequate assessment in the trauma resuscitation bay. Any subsequent laparotomy before the discharge of the NOM cases, were then classified as a delayed laparotomy (DOM) and recorded appropriately. There were no exclusion criteria. Figure 1 illustrates these definitions with the institutional algorithm for PAT. All patients with a ‘negative’ abdominal examination and/or a ‘negative’ CT investigation, were admitted for abdominal observation. Patients with left thoracoabdominal (TA) PAT wounds were subjected to abdominal observations (as described in the discussion below) before undergoing a diagnostic laparoscopy to exclude an occult diaphragm injury.

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis of the PAT database included: basic demographics; admission of illicit drug use; presenting vital signs; blood investigations; number of penetrating traumatic insults; penetrating wound positions; presence of peritonism and/or evisceration; indication for laparotomy; radiological investigations and interventions; operative or nonoperative management; laparotomy findings- therapeutic, non-therapeutic, or negative; abdominal visceral injuries and associated injuries. When recording the indication for laparotomy, the most clinically urgent reason was used. However, when the indication was unclear, no entry was made, and should two indications have been seen as equally urgent, both were recorded. The presence of peritonism was recorded separately. Injury severity was described by the Injury Severity Score (ISS); the Revised Trauma Score (RTS); Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS); Penetrating Abdominal Trauma Index (PATI); and Kampala Trauma Score (KTS) [11, 12, 14,15,16]. Outcome variables included Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission; hospital length of stay (LOS); hospital readmission; relaparotomy; in-hospital complications; and mortality. Complications were defined as any deviation from the normal postoperative course requiring the need for: pharmacological; endoscopic; interventional radiological; or surgical treatment, and were categorised according to the Clavien-Dindo classification system [17]. Multi-trauma injury patients were classified as having an AIS of greater than or equal to three in at least two organ systems.

Comparisons were then made between subgroups of patients managed operatively, both immediately and delayed (DOM), as well as non-operatively (NOM). Univariate predictors of DOM were also explored. The positive predictive value (PPV) of operative indications for therapeutic laparotomy was calculated and outcomes between the subgroups were compared.

For the descriptive analysis, continuous data were summarised using means and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) if normally distributed, whereas medians and interquartile range (IQR) was used for non-normally distributed data. For inferential statistics, parametric tests were performed such as Chi-square tests or where appropriate the non-parametric equivalent. Furthermore, univariate logistic regression was performed to determine associations for delayed non-operative management and reported with odd ratios and 95% CIs. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. STATA® 14 software was utilized for statistical analysis.

Results

Presenting characteristics and injury profile

Descriptive assessment

In total, 805 consecutive patients with penetrating abdominal trauma were managed over the 2 year period. There were 502 (62.4%) and 303 (37.6%) patients with gunshot (GSW) and stab wounds (SW), respectively. The overwhelming majority were young men (94.7%), with a mean age of 28.3 years (95% CI 27.7–28.9) and median ISS of 13 (IQR 9–22). There was a preponderance of poly-assault, and more than one penetrating injury was present in 68.2% of SW; and 64.0% of GSW. Cumulative abdominal wall penetrative wounds were abdominal (anterior and back/flank) in 696 (86.5%); thoracoabdominal in 332 (41.2%); and pelvic in 192 (23.9%) injuries. Three hundred and sixty-eight (45.7%) presented with peritonism, more commonly in GSW (59.4%) compared to SW (23.1%) (p < 0.001). The three most commonly injured organs overall were: colon—177 (22.0%); liver—189 (23.5%) and small bowel—241 (29.9%). Multi-trauma injuries were found in 40.9% of cases overall. This included 106 (35%) SW, and 223 (44.4%) GSW patients (p = 0.005). Table 1 summarises the presenting characteristics and injury profile of the cohort.

Comparative assessment

Successful non-operative management was achieved in 304 (37.8%) patients and 501 (62.2%) were managed operatively. Of these, 477 (59.3%) underwent immediate laparotomy, and 24 (3.0%) delayed operative management. Table 2 compares the presentation; management; and outcome of the cohort compared by the three possible operative outcomes i.e. immediate laparotomy (IOM); delayed operative management (DOM); and non-operative management (NOM). The young, male demographic was maintained across the three groups with no significant deviations. Patients managed by immediate laparotomy were more likely to have sustained a GSW; anterior abdominal wound; and higher median ISS. The DOM & NOM groups were more likely to have undergone a CT scan, but there was no significant difference in the use of interventional radiology between the three groups. CT scans were obtained preoperatively in some patients for investigation of the urinary tract system in the presence of haematuria. This allows for Grade 3 and lesser renal injuries to be managed conservatively intraoperatively by not entering Gerota’s fascia.

On univariate analysis, number (OR 1.05; 95% CI 0.92–1.19); location (OR 1.1; 95% CI 0.79–1.25); and mechanism of injuries (OR 0.49; 95% CI 0.22–1.11) were not associated with DOM (i.e. failed NOM). Rates of therapeutic laparotomy were achieved in 90.3% of the immediate; and 80.3% in the DOM cohorts. On arrival, immediate laparotomy was performed for haemodynamic instability in 44 (5.5%) patients (PPV 93.2%); peritonism in 298 (37.2%) patients (PPV 93.3%); unreliable clinical assessment in 21(2.6%) patients (PPV 66.7%); radiological findings in 54 (6.7%) patients (PPV 87.0%); and for organ evisceration in 29 (3.6%) patients (PPV 89.7%). In the DOM cohort, 2 (8.3%) became haemodynamically unstable (PPV 100%): 14 (58.3%) developed peritonism (PPV 85.7%): 10 (41.7%) had positive radiological findings (PPV 87.5%); and 8 (33.3%) developed signs of sepsis (PPV 87.5%). Table 3 describes PPV of operative indications for therapeutic laparotomy in the immediate laparotomy, and DOM cohorts.

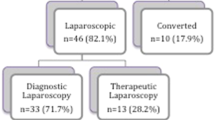

Nineteen diagnostic laparoscopies were performed to exclude an occult diaphragm injury. Six (31.5%) diaphragm injuries were detected; three were repaired laparoscopically and three were repaired via laparotomy.

The mortality rate was 11.3% in immediate laparotomy; 1.3% in the NOM, and 0% in the DOM subgroups (Table 2). This trend differed slightly with the complication rate: immediate laparotomy—41.5%; DOM—33.3%; followed by NOM group—10.0%. Although the rates of mortality and morbidity of the NOM cohort are far lower, the rate of complications, ICU admission, reoperation and missed injuries were no different in the immediate laparotomy; and DOM cohorts (p > 0.05). All complications were classified by Clavien-Dindo grade and are presented by operative strategy in Table 4. The grade of complication did not differ by operative strategy (p > 0.05).

Discussion

The concept to selective conservatism for PAT has gained traction ever since Shaftan’s landmark paper in 1960 when he challenged the dogma of mandatory explorative laparotomy [2]. Various subsequent studies stretching from opposite corners of the world have further supported this selective approach with excellent results [3,4,5,6,7]. These aforementioned authors all concluded that patients presenting with PAT in the absence of haemodynamic instability; peritonism; organ evisceration; positive radiological findings; or an unreliable clinical examination can be managed expectantly, without increased morbidity or mortality. However, due to the rapid evolution of this approach, finer details and smaller subgroup analysis is needed to convince sceptics.

Here we present one of the largest; and most detailed prospective series to date, comparing various operative strategies side by side, in a composite PAT cohort (SW and GSW). We used these three operative strategies, namely: immediate laparotomy; NOM; and DOM (i.e. “failed” NOM) to dissect out the outcomes of every sub-group and compare alongside one another.

Various authors have noted that mandatory laparotomy policies for penetrating abdominal trauma result in unnecessary laparotomy rates ranging from 5.3 to 27% for GSW, and 23 to 53% for SW [18, 19]. This implies that nearly a quarter of GSW and almost half of all abdominal SW do not require a laparotomy, however, our findings were closer to a third and two thirds, respectively.

Given these striking findings, the important learning objective for any trauma unit managing PAT must be how to implement selective NOM to decrease the number of non-therapeutic laparotomies in PAT (both SW and GSW) without an increased missed injury rate; and without causing increased mortality or morbidity in the failed NOM patients. This manuscript demonstrates this with our protocolised approach involving an initial, methodical assessment and resuscitation utilizing protocolized guidelines, (such as that proposed in Advanced Trauma Life Support™) followed by the decision whether the patient must proceed for immediate surgery; further investigation; or observation alone [20].

Indications for immediate laparotomy include haemodynamic instability (indicating ongoing haemorrhage); peritonism (suggesting abdominal contamination); organ evisceration or impalement; unreliable clinical examination; or radiologically confirmed bladder or ureteric injuries [19, 21, 22].

Once the aforementioned indications for mandatory laparotomy have been excluded, the patient can be considered for NOM, either immediately or following further investigation. In 2015 Navsaria et al. proposed a selective rather than mandatory use of CT scans in abdominal GSW management, where absolute indications for imaging included right upper quadrant / right thoracoabdominal injury (to exclude liver injury); and haematuria (to exclude urogenital injury) [8]. In this study presented here, all except one of the indications for immediate laparotomy had a PPV of greater than 87%, namely, unreliable clinical examination, which had a PPV of just 66.7%. This is, however, not an unexpected finding for this indication, if referencing the literature [21]. The reason for this is that even with the advances in technology, CT scans only display a sensitivity of 91–97%, specificity of 96–98%, and accuracy of 96–98% for detecting intra-abdominal injuries that actually require laparotomy in patients with abdominal GSWs [23,24,25]. A negative CT scan thus does not exclude an intrabdominal injury. Therefore, in patients with PAT and concomitant head injuries and/or high-spinal cord injuries (where the serial abdominal examination is unreliable), despite the high rate of negative explorations, a laparotomy is justified.

Non-operative management should rarely (if ever) involve discharging a patient directly from the emergency department. This practice is not safe until the sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of CT for penetrating abdominal trauma is 100%. Thus, we and other authors feel it should be routine practice to admit all patients with PAT for further observation [21].

During this admission the patient is kept nil per mouth, maintaining hydration with an isotonic intravenous crystalloid solution. Anti-biotics are withheld, and analgesia administered as necessary. Routine four-hourly vital sign observations and regular serial clinical assessment (preferably by the same clinician) must be carried out. After 24hrs of observation, should the patient’s abdominal examination or haemodynamic status not deteriorate, the patient can be fed. Should they not develop foregut symptoms (nausea of vomiting) they can be considered for discharge home [26, 27]. Further investigation during this admission is at the discretion the treating clinician. However, fever and a rise in WCC need to be interpreted with caution. Failure of NOM prompts operative intervention and is usually signalled by peritonism; ongoing blood loss; or concern of sepsis. Of those managed by DOM in our cohort, 2 (8.3%) became haemodynamically unstable (PPV 100%); 14 (58.3%) developed peritonism (PPV 85.7%); 10 (41.7%) had positive radiological findings (PPV 87.5%); and 8 (33.3%) developed signs of sepsis (PPV 87.5%). The aforementioned significance of radiology in decision making in this DOM group is contrary to a recent systematic review and metanalysis of GSW in PAT [28].

Historically PAT to varying abdominal regions were managed differently, with clinicians being more hesitant to treat back and pelvic injuries non-operatively, fearing occult hollow-viscous injuries [22, 29,30,31]. However, our experience as well as prior publications refute this, indicating that GSW and SW to the anterior abdomen; back; flank and pelvis can all be approached with the common principle described above [31,32,33,34,35]. We found that although anterior abdominal wound is associated with immediate laparotomy, unlike a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis, abdominal wound position is not associated with DOM (i.e. “failed NOM”) [28]. The abdominal region injured may however, guide the choice of diagnostic adjuncts in the work-up [21, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39].

Unsurprisingly, higher injury severity scores (ISS) and GSW were independently associated with immediate laparotomy, however, neither were significant in differentiating NOM from DOM cases in this study. In other words, both GSW and the more severely injured patients have a higher chance of needing an immediate laparotomy, but should that not be clinically indicated, their chances of NOM success are no different to the rest.

Contrary to Zafar et al. reporting that failed NOM is associated with increased mortality, two subsequent systemic reviews by Lamb et al. in 2014, and Al Rawahi et al. in 2018, showed no difference in outcome between those undergoing early and late laparotomies, which is in keeping with our findings [28, 40, 41]. In this series, successful non-operative management was achieved in 304 (37.7%) patients, with a significantly lower morbidity and mortality rate compared to the operatively managed patients. This is in-spite of the fact that the four NOM mortalities recorded were unrelated to PAT (one fatal CVA; and three transhemispheric GSW, for which the patients could better be described as palliated, rather than managed non-operatively). However, in addressing the abovementioned concern, it is more important to note that the DOM subgroup presented here, did not have worse outcomes (mortality; complications; ICU admissions; reoperations; or missed injuries) than those managed by immediate laparotomy (p > 0.05). Thus, implying that selective conservatism in PAT in a high volume tertiary referral trauma centre for civilian SW and GSW is not only effective but safe too. Numerous other publications support this finding, by having shown that patients managed with selective non-operative management compare favourably to operative management as they have shorter admission periods and equivalent, or reduced mortality [8, 9, 26, 42].

Our findings must be interpreted within the study’s limitations. This is a single centre study at a high volume trauma unit, which experiences a high incidence of PAT. Whether these findings are generalizable and similar results can be expected in lower volume trauma units or areas with a low incidence of penetrating trauma is unknown, however, selective NOM has been reported to be safe in lower volume centres too [43]. The prospective nature of this study was enabled by the real-time electronic trauma registry. This is a clinician entered the database and although no data validation of the PAT patients occurred in this study, validation studies of this database have been performed previously [10].

Conclusion

Patients presenting with PAT in the absence of haemodynamic instability; peritonism; organ evisceration; unreliable clinical examination; and positive radiological findings can be managed expectantly without increased morbidity or mortality. Figure 2 summarises the current study findings.

Data availability

References

Western Cape mortality profile, 2013. Available at: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/assets/departments/health/mortality_profile_2016.pdf, Accessed Nov 30, 2018.

Shaftan GW. Indications for operation in abdominal trauma. Am J Surg. 1960;99:657–64.

van Haarst EP, van Bezooijen BP, Coene PP, Luitse JS. The efficacy of serial physical examination in penetrating abdominal trauma. Injury. 1999;30(9):599–604.

Leppaniemi AK, Haapiainen RK. Selective nonoperative management of abdominal stab wounds: prospective, randomized study. World J Surg. 1996;20(8):1101–6.

Nance FC, Cohn I Jr. Surgical judgment in the management of stab wounds of the abdomen: a retrospective and prospective analysis based on a study of 600 stabbed patients. Ann Surg. 1969;170(4):569–80.

Tsikitis V, Biffl WL, Majercik S, Harrington DT, Cioffi WG. Selective clinical management of anterior abdominal stab wounds. Am J Surg. 2004;188(6):807–12.

Ball CG, Nicol AJ, Navsaria PH. The contribution of a South African collegue to evolution and innovation of trauma surgery. T Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(1):217–8.

Navsaria PH, Nicol AJ, Edu S, Gandhi R, Ball CG. Selective Nonoperative Management in 1106 patients with abdominal gunshot wounds: conclusions on safety, efficacy, and the role of selective CT imaging in a prospective single-center Study. Ann Surg. 2015;261(4):760–4.

Peev MP, Chang Y, King DR, Yeh DD, Kaafarani H, Fagenholz PJ, et al. Delayed laparotomy after selective non-operative management of penetrating abdominal injuries. World J Surg. 2015;39(2):380–6.

Zargaran E, Spence R, Adolph L, Nicol A, Schuurman N, Navsaria P, et al. Association between real-time electronic injury surveillance applications and clinical documentation and data acquisition in a South African trauma center. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(5):e180087.

AAST. Injury Scoring Scale. Available at: https://www.aast.org/library/traumatools/injuryscoringscales.aspx, Accessed: Nov 25, 2018.

Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Malangoni MA, Jurkovich GJ, Champion HR. Scaling system for organ specific injuries. Curr Opin Crit Care. 1996;2(6):450–62.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Copes WS, Gann DS, Gennerelli TA, Flanagan ME. A Revision of the Trauma Score. J Trauma. 1989;29(5):623–9.

Kobusingye OC, Lett RR. Hospital-based trauma registries in Uganda. J Trauma. 2000;48(3):498–502.

Moore EE, Dunn EL, Moore JB, Thompson JS. Penetrating abdominal trauma index. J Trauma. 1981;21(6):439–45.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–13.

Friedmann P. Selective management of stab wounds of the abdomen. Arch Surg. 1968;96(2):292–5.

Como JJ, Bokhari F, Chiu WC, Duane TM, Holevar MR, Tandoh MA, et al. Practice management guidelines for selective nonoperative management of penetrating abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 2010;68(3):721–33.

ATLS Subcommittee, American College of Surgeons’ committee on Trauma, International ATLS working group. Advanced trauma life support (ATLS®): the ninth edition. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(51):1363–6.

Biffl WL, Leppaniemi A. Management guidelines for penetrating abdominal trauma. World J Surg. 2015;39(6):1373–80.

Butt MU, Zacharias N, Velmahos GC. Penetrating abdominal injuries: management controversies. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:19.

Velmahos GC, Constantinou C, Tillou A, Brown CV, Salim A, Demetriades D. Abdominal computed tomographic scan for patients with gunshot wounds to the abdomen selected for nonoperative management. J Trauma. 2005;59(5):1155–60.

Múnera F, Morales C, Soto JA, Garcia HI, Suarez T, Garcia V, et al. Gunshot wounds of abdomen: evaluation of stable patients with triple-contrast helical CT. Radiology. 2004;231(2):399–405.

Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE, Chiu WC, Killeen KL, Hogan GJ, Scalea TM. Penetrating torso trauma: triple-contrast helical CT in peritoneal violation and organ injury—a prospective study in 200 patients. Radiology. 2004;231(3):775–84.

Navsaria PH, Berli JU, Edu S, Nicol AJ. Non-operative management of abdominal stab wounds—an analysis of 186 patients. S Afr J Surg. 2007;45(4):128–30.

Inaba K, Demetriades D. The nonoperative management of penetrating abdominal trauma. Adv Surg. 2007;41:51–62.

Al Rawahi AN, Al Hinai FA, Boyd JM, Doig CJ, Ball CG, Velmahos GC, et al. Outcomes of selective nonoperative management of civilian abdominal gunshot wounds: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:55.

Vanderzee J, Christenberry P, Jurkovich GJ. Penetrating trauma to the back and flank. A reassessment of mandatory celiotomy. Am Surg. 1987;53(4):220–2.

DiGiacomo JC, Schwab CW, Rotondo MF, Angood PA, McGonigal MD, Kauder DR, et al. Gluteal gunshot wounds: who warrants exploration? J Trauma. 1994;37(4):622–8.

Demetriades D, Rabinowitz B, Sofianos C, Charalambides D, Melissas J, Hatzitheofilou C, et al. The management of penetrating injuries of the back. A prospective study of 230 patients. Ann Surg. 1988;207(1):72–4.

Peck JJ, Berne TV. Posterior abdominal stab wounds. J Trauma. 1981;21(4):298–306.

Navsaria PH, Edu S, Nicol AJ. Nonoperative management of pelvic gunshot wounds. Am J Surg. 2011;201(6):784–8.

Velmahos GC, Demetriades D, Cornwell EE. Transpelvic gunshot wounds: Routine laparotomy or selective management? World J Surg. 1998;22(10):1034–8.

Velmahos GC, Demetriades D, Cornwell EE, Asensio J, Belzberg H, Berne TV. Gunshot wounds to the buttocks: predicting the need for operation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40(3):307–11.

Biffl WL, Moore EE. Management guidelines for penetrating abdominal trauma. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010;16(6):609–17.

Biffl WL, Kaups KL, Pham TN, Rowell SE, Jurkovich GJ, Burlew CC, et al. Validating the Western Trauma Association algorithm for managing patients with anterior abdominal stab wounds: a Western Trauma Association multicenter trial. J Trauma. 2011;71(6):1494–502.

Biffl WL, Kaups KL, Cothren CC, Brasel KJ, Dicker RA, Bullard MK, et al. Management of patients with anterior abdominal stab wounds: a Western Trauma Association multicenter trial. J Trauma. 2009;66(5):1294–301.

Thompson JS, Moore EE, Van SD, Moore JB, Galloway AC. The evolution of abdominal stab wound management. J Trauma. 1980;20(6):478–84.

Zafar SN, Rushing A, Haut ER, Kisat MT, Villegas CV, Chi A, et al. Outcome of selective non-operative management of penetrating abdominal injuries from the North American National Trauma Database. Br J Surg. 2012;99:155–64.

Lamb CM, Garner JP. Selective non-operative management of civilian gunshot wounds to the abdomen: a systematic review of the evidence. Injury. 2014;45(4):659–66.

Velmahos GC, Demetriades D, Toutouzas KG, Sarkisyan G, Chan LS, Ishak R, et al. Selective nonoperative management in 1,856 patients with abdominal gunshot wounds: should routine laparotomy still be the standard of care? Ann Surg. 2001;234(3):395–403.

Fikry K, Velmahos GC, Bramos A, Janjua S, de Moya M, King DR, et al. Successful selective nonoperative management of abdominal gunshot wounds despite low penetrating trauma volumes. Arch Surg. 2011;146(5):528–32.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS: data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation. RS: data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation. PN: study design, database design, chief supervisor to Sander, manuscript critique, edits and rewrites. JE, MH: manuscript preparation and edit, statistical analysis input. AN and SE: manuscript rewrite and edits, data collection.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

University of Cape Town Human Ethics Research Committee: UCT/HREC Ref: 443/2017.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sander, A., Spence, R., Ellsmere, J. et al. Penetrating abdominal trauma in the era of selective conservatism: a prospective cohort study in a level 1 trauma center. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 48, 881–889 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-020-01478-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-020-01478-y