Abstract

Background

Health-related quality of life is a multidimensional concept to assess the impact of medical interventions from an individual perspective. This concept is important to evaluate benefits of heart transplantation. This systematic review was conducted to determine (1) posttransplant health-related quality of life in heart transplantation patients and (2) influencing factors of health-related quality of life.

Methods

A systematic review of cross-sectional, prospective and mixed methods studies published from November 2007 to November 2017 was conducted on PsycINFO, PSYNDEX and PubMed using a combination of the keywords heart transplantation, heart transplantation patient, quality of life, and health-related quality of life.

Results

A total of 14 studies with a cross-sectional design, 6 studies with a prospective design and 2 mixed-methods studies were identified. The stability of health-related quality of life up to 10 years after transplantation has been reported. Most often generic scales, such as SF-36 (8) and WHOQoL-BREF (7) were used for data collection. Demoralization, depression, pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, sexual dysfunction, and poor oral health influence health-related quality of life negatively, whereas social and family support have a positive impact.

Conclusion

Although health-related quality of life is positively influenced by transplantation, further research regarding gender differences is needed. Disease-specific scales were rarely used.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Die gesundheitsbezogene Lebensqualität ist ein multidimensionales Konzept, das u. a. der Erhebung des Einflusses von medizinischen Interventionen auf das individuelle Wohlbefinden dient. Herztransplantationen beeinflussen die gesundheitsbezogene Lebensqualität grundlegend. Ziel dieses systematischen Reviews ist, anhand vorliegender Studien einen Überblick über die gesundheitsbezogene Lebensqualität nach Herztransplantationen zu geben und Einflussfaktoren genauer zu beschreiben.

Methoden

Das systematische Review schließt quantitative Studien ein (Querschnittstudien, prospektive Studien und Studien mit gemischtem Design), die zwischen November 2007 und November 2017 veröffentlicht wurden. Das Review wurde auf PsycINFO, PSYNDEX und PubMed mit einer Kombination der Schlüsselwörter „heart transplantation“, „heart transplantation patient“, „quality of life“ und „health-related quality of life“ durchgeführt.

Ergebnisse

Insgesamt 14 Querschnittstudien, 6 prospektive Studien und 2 Studien mit gemischtem Design wurden gefunden. Es zeigt sich eine stabile gesundheitsbezogene Lebensqualität bis zu 10 Jahre nach Herztransplantation. Für die Datenerhebung wurden am häufigsten unspezifische Skalen wie SF-36 und WHOQoL-BREF verwendet. Als negative Einflussfaktoren auf die gesundheitsbezogene Lebensqualität sind Demoralisierung, Depression, Schmerzen, gastrointestinale Beschwerden, sexuelle Dysfunktion und schlechter Zahnstatus zu benennen. Soziale Unterstützung durch die Familie wirkt sich positiv aus.

Diskussion

Defizite in der bisherigen Forschung bestehen vor allem in der fehlenden Betrachtung des Einflusses der Geschlechtszugehörigkeit der Patienten sowie in der seltenen Verwendung krankheitsspezifischer Erhebungsinstrumente.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There have been numerous attempts at defining the concept of quality of life (QoL) due to its multidimensionality and subjectivity. QoL is influenced by socioeconomic status, functioning in everyday life, life satisfaction and many other factors depending on the evaluation context [1, 2]. The term health-related quality of life (HRQoL) describes the impact of disease or chronic conditions on QoL. Key aspects of HRQoL are the following: physical status and functioning; psychological status and individual well-being; social interactions; and economic status [3]. Medical interventions, such as organ transplantation, can influence HRQoL positively. To incorporate impacts of disease as reported by the patient and to evaluate effects of interventions, adequate measures to determine HRQoL are needed. Assessment tools of HRQoL can be classified as disease-, population-, dimension or utility-specific, individualised or generic (Table 1; [4,5,6,7]). Assessment tools of disease-specific HRQoL focus on patient populations with specific diseases or chronic conditions, such as heart failure.

Background

In patients with chronic heart failure, an increased risk of hospital admission, increased symptom prevalence and symptom burden has been linked to poor HRQoL [8, 9]. Gender, age, exercise, and social support have been stated as influencing factors of HRQoL in patients with heart failure [10]. Heart transplant candidates are a special subgroup among patients with cardiac disease, since one requirement of transplantation is having symptoms of congestive heart failure with severe limitations of physical activity (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class IV). Therefore, HRQoL is adversely affected by limited physical functioning in this population [11]. HRQoL after heart transplantation is influenced by physical, psychological and sociodemographic factors.

Methods

We conducted this systematic review to determine (1) posttransplant HRQoL in heart transplantation (HTx) patients and (2) influencing factors of HRQoL.

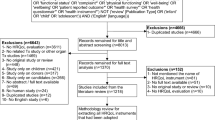

Studies including at least one measure to assess HRQoL in adult heart transplant recipients were systematically reviewed in a literature research on PubMed, PsycINFO and PSYNDEX. This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) statement [12]. A systematic literature review of studies addressing the domains of HRQoL in HTx patients and using validated HRQoL scales was conducted on PubMed, PsycINFO and PSYNDEX in November 2017. Further information on the search strategy can be found in Fig. 1. Studies published in English between 1 November 2007 and 1 November 2017 and available in full text were included to ensure relevance. Posttransplant HRQoL studies at any length of follow-up as well as cross-sectional, prospective and mixed methods studies were eligible. Articles which did not report data collection methods or inclusion/exclusion criteria, did not use validated measures of HRQoL, focused on HRQoL before transplantation and in transplantation of other solid organs, or only assessed psychological status in terms of distress or functional status without considering HRQoL were excluded. Additionally, case reports, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were excluded because only studies directly assessing HRQoL and addressing a larger number of HTx patients were eligible for inclusion. Overall, 739 articles were found through database researching. Titles and abstracts were screened by the authors to identify eligible studies after removal of duplicates. Full-text articles were assessed in all cases where inclusion criteria were met. Any disagreements in the selection of studies were resolved by discussion. The study selection process and reasons for exclusion are described in Fig. 1.

Studies were evaluated by using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement to ensure quality [13]. A maximum of 22 points can be reached within STROBE. Studies reaching scores above 19 points were considered as having very high quality, 18–15 points as high quality, 14–11 points as moderate quality and 10 points or less as low quality. Retrieved data regarding sample size, sample characteristics, domains of HRQoL, and influencing factors of HRQoL were collected in supplemental Table 1.

Results

22 studies met the inclusion criteria: 14 studies with a cross-sectional design, 6 studies with a prospective design and 2 mixed-methods studies were included. The studies assessed between 12 and 555 HTx patients, with an average sample size of 119.78 patients. Participants in these studies were mostly male (range 62.8–100%). The age within groups ranged from 43 ± 13 years to 61.2 ± 11.4 years. Frequently reported underlying diagnoses as a reason for HTx were nonischaemic cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy. Three studies used the same data sample of 555 HTx patients transplanted between 1990 and 1999 in four American medical centres [14,15,16]. For more information on each study, see supplemental Table 1.

Most frequently, generic measurements for HRQoL were found. The SF-36 was used (8 times); the abbreviated form SF-12 was encountered once. Secondly, WHOQoL-BREF was applied (7 times; Table 2). Overall, 49 different scales were used in 20 samples, covering a total of 2697 patients.

Changes of HRQoL over time

Cross-sectional studies

Two cross-sectional studies reported the stability of HRQoL using WHOQoL-BREF and SF-36 at one, three, four to five, and five years posttransplant (Fig. 2; [17, 18]). Only one cross-sectional study highlighted a decrease in 5Q-5D Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores from 6, 12, 36, 60 months to 10 years after transplant (p = 0.011; Fig. 3). Overall QoL improved significantly in a comparison of one sample 6 months posttransplant to another sample 120 months posttransplant (77.72 to 80.51, p = 0.017) [19].

Changes in SF-36 subscales over time (data of Kugler et al. [22], patients 1 to 2 and 6 to 8 months after transplant n = 54; Saeed et al. [18], patients 1, 3, and 5 years after transplant, n = 80, n = 127, n = 116; Galeone et al. [20], patients > 20 years after transplant, n = 81). PF physical functioning, RP role physical, BP bodily pain, GH general health, VT vitality, SF social functioning, RE role emotional, MH mental health

Significantly lower scores in all aspects of SF-36, indicating worse HRQoL, except for mental health at 1, 3 and 5 years posttransplant in comparison to the age- and gender-matched general population were determined in one cross-sectional British study [18]. In their cross-sectional comparison of 81 HTx patients who survived longer than 20 years posttransplant (mean time since transplant 23 ± 3 years) to 52 HTx patients (surviving 6 ± 5 years posttransplant), Galeone et al. reported significantly lower SF-36 scores in the physical functioning (61 vs 74), general health (49 vs 58), vitality (49 vs 58) and social functioning (61 vs 77) and in the physical (57 vs 67) and mental component summary (58 vs 68) in the older patient sample (all below p < 0.05) [20].

Prospective studies

Kugler et al. described a significant increase in the physical and psychosocial domains of HRQoL (according to SF-36) from before transplant to 60 months after transplant without providing exact data on SF-36 subscales [21]. From 4–8 weeks to 5–7 months posttransplant, only an increase in the role physical subscale of SF-36 was found (75.1 vs 87.5, p < 0.03) [21]. According to Jakovljevic et al. [23], HRQoL, measured with the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ), was significantly better at 3, 6, and 12 months posttransplant (p < 0.05, scores decreasing from 72 to 29, indicating better overall HRQoL) in comparison to patients with a left ventricular assist device (LVAD).

Changes in physical function and bodily pain

With regard to physical function, HRQoL increased significantly in HTx patients in comparison to LVAD patients at 12 months [22, 23]. Scores regarding bodily pain differed when compared to general population norms [22, 24]. At 6 months posttransplant, a significant improvement of bodily pain was reported with better scores than a general population sample [22], whereas patients with a mean time of 4.5 years since transplant had significantly worse scores regarding bodily pain than the general population [24].

Influence of sociodemographic factors on HRQoL

Satisfaction with the physical (58.3% vs 62.8%) and psychological domains (58.3% vs 65.1%) of HRQoL was lower in female patients, whereas female patients were more satisfied with social relations (100% vs 53.5%) and environmental factors (83.3% vs 65.1%) [25]. Delgado et al. reported a negative association of female gender with EQ-5D scores [19]. There was no statistically significant difference in SF-12 scores between female and male patients in one cross-sectional study [26]. In adults older than 60 years, a greater satisfaction with QoL and social support (according to the QLI) was reported in comparison to adults younger than 45 years and aged between 45 and 59 years (p < 0.001) [15].

Influence of psychological factors on HRQoL

Demoralized patients had significantly lower scores in all domains of WHOQoL-BREF, indicating worse HRQoL, than nondemoralized patients (all domains below p ≤ 0.01) [27]. Depression (Beck’s Depression Inventory [BDI] score >8) is negatively correlated with the physical (WHOQoL-BREF, r = −0.45, p < 0.01), social (r = −0.49, p < 0.05) and psychological domains (r = −0.30, p > 0.01) of HRQoL in one study and to physical and mental component summaries in another (SF-36, r = −0.56, r = −0.66, p < 0.05, p < 0.01) [28, 29]. Depressed patients had significantly lower scores in all SF-36 domains (all below p < 0.0013) [30].

At one year and over five years posttransplant, family support was a predictor of the physical (p < 0.01) and psychosocial domains (p < 0.01) of HRQoL. The influence of tangible support on physical (r = 0.29, p < 0.05), social (r = 0.28, p < 0.05) and environmental (r = 0.26, p < 0.05) domains of HRQoL (WHOQoL-BREF) measured by Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) is shown. ISEL total score and belonging were associated with physical (r = 0.31, p < 0.05; r = 0.35, p < 0.01) and social domains of HRQoL (r = 0.37, p < 0.01; r = 0.41, p < 0.01), and ISEL appraisal with social QoL (r = 0.28, p < 0.05) [31]. Self-perceived family support was a predictor of the physical and mental component summary in multivariate analysis [28]. Satisfaction with emotional, tangible, and social support was associated with better HRQoL (low scores indicating more satisfaction, r = −0.60, r = −0.50, r = −0.54, p < 0.0001) [16].

All domains of WHOQoL-BREF were correlated with different coping strategies (positive correlation with focus on problem and negative correlation with focus on emotion). Psychological, social and environmental domains were associated with focus on social support [32]. Overall HRQoL (WHOQoL-BREF) correlated significantly with sense of coherence (r = 0.66), optimism (r = 0.53), and self-efficacy (r = 0.62; all p < 0.004) [33].

Influence of physical factors on HRQoL

Holtzman et al. assessed pain in a sample of 92 HTx patients [24]. 10.9% of patients reported having severe or very severe pain. In contrast to one general population sample, patients with at least a mild level of pain reported significantly worse scores in all domains of SF-36, indicating worse HRQoL, whereas HTx patients with no or little pain described having similar levels of social functioning, role interference due to emotional difficulties, and mental health [24].

Patients with severe gastrointestinal symptoms (Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale >1) reported lower scores in all SF-36 domains [34]. Phan et al. [26] underlined high levels of sexual dysfunction (50% of women and 78% of men, mean age 61.2 ± 11.4 years). Patients with sexual dysfunction had significant lower subscores of SF-12 in general health (41.1 vs 52.8, p = 0.02), physical health (38.6 vs 50.0, p = 0.02), physical functioning (38.2 vs 50.0, p = 0.01) and physical role limitation (39.5 vs 50.3, p = 0.01) than patients without sexual dysfunction. Additionally, a poor perceived impact of oral health on HRQoL was reported (mean score 24.43 of a total 196 points) [35].

At 5–10 years after transplant, social and economic satisfaction, domains of QLI, were a significant predictor of survival (hazard ratio 0.05, range 0.00–0.75, p = 0.03) in multivariate analysis, as were education, coexisting cardiovascular and hematologic illnesses, NYHA classes I and II, compliance with the medical regimen, cumulative infections and being married. Patients surviving 5–10 years after heart transplant reported significantly better HRQoL than nonsurviving patients (higher scores in all domains of QLI) [14].

Discussion

Regarding the development of HRQoL, the stability of HRQoL up to 10 years posttransplant is to be highlighted. Two cross-sectional studies support the long-term stability of QoL up to 5 years posttransplant. In comparison to a general population sample, significantly lower scores in all aspects of SF-36 except for mental health at 1, 3 and 5 years posttransplant were determined. In summary, older patients were more satisfied with HRQoL. Demoralized and depressed patients had lower scores in all SF-36 domains. Satisfaction with social, emotional, tangible and family support was associated with better overall HRQoL scores and physical and psychosocial domains. Several coping strategies (focus on problem, focus on social support) correlated with better HRQoL. Pain, sexual dysfunction and gastrointestinal symptoms have a negative impact on HRQoL. Social and economic satisfaction, components of QLI, were significant predictors of survival at 5–10 years after transplantation. Generic scales such as SF-36 (8 times) and WHOQoL-BREF (7 times) were encountered most often in data assessment.

The impact of gender on HRQoL in HTx patients is difficult to determine since gender is rarely analyzed separately. The majority of assessed patients in all studies were male, and results regarding gender differences were inconclusive. Small gender differences in HRQoL of heart failure patients have been reported [36, 37]. The examination of a possible gender difference is therefore of particular interest.

Conway et al. described in their review of qualitative studies of HRQoL in HTx patients that HTx patients tend to have negative psychological experiences, such as depression. Psychological well-being was positively influenced by social support in their analysis [38]. Our results regarding the impact of depression and family and social support on HRQoL support these findings.

Greater symptom burden, including pain, sexual dysfunction, and several gastrointestinal symptoms, and prevalence, lower age and higher NYHA classification were predictors of worse HRQoL in heart failure patients [9]. Again, our results highlight the negative impact of pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, sexual dysfunction and poor oral health on overall HRQoL.

Nonsurviving heart failure patients in a 3-year follow-up study reported worse overall HRQoL (according to MLHFQ) and a decrease in physical functioning, physical role limitation, bodily pain and general health (Medical Outcome Study 36-item General Health Survey, RAND36) than survivors at baseline [7]. Similar results for HTx patients surviving 5–10 years have been described [14].

Limitations

Most of the included studies had a cross-sectional design. Cause and effect relations cannot be determined in this study design, limiting validity and assessment of confounding bias. Regarding this analysis, a potential selection bias must be addressed, since the selected articles only regard adult HTx patients in the context of HRQoL. In addition, only a small sample of articles was chosen. This reduces generalizability. Furthermore, articles not published in English or with a qualitative approach were excluded.

Conclusion

This systematic review has reported the development of posttransplant HRQoL in HTx patients, influencing factors of HRQoL, and frequently used assessment tools of HRQoL. Further research regarding possible gender differences in HRQoL of HTx patients is needed. The negative impact of psychological and physical factors, such as depression, pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, and sexual dysfunction, on HRQoL of HTx patients is to be considered in clinical research and patient care. Research about other possible influencing factors on HRQoL of HTx patients, that have already been reported in heart failure patients, needs to be conducted since our review does not provide information on important sociodemographic characteristics such as education and marital status [39]. With regard to the scales used, a lack of sensitivity of SF-36 and QLI in a small sample of cardiac patients has been reported [40]. Generic scales to assess HRQoL were mainly used, which are likely to have a lower sensitivity than disease-specific scales. In only one patient sample, the QLI cardiac version was used for data collection. For this reason, small changes in QoL were possibly not detected. Therefore, disease specific scales need to be incorporated in future research to specify results. Awareness of various influencing factors, such as pain and sexual dysfunction, on HRQoL in HTx patients is required to improve screening and communication with patients.

References

Farquhar M (1982) (1995) Elderly people’s definitions of quality of life. Soc Sci Med 41(10):1439–1446

Parmenter TR (1994) Quality of life as a concept and measurable entity. Soc Indic Res 33(1–3):9–46

Raphael D, Renwick R, Brown I, Rootman I (1996) Quality of life indicators and health: current status and emerging conceptions. Soc Indic Res 39(1):65–88

Garratt A, Schmidt L, Mackintosh A, Fitzpatrick R (2002) Quality of life measurement: bibliographic study of patient assessed health outcome measures. BMJ 324(7351):1417

McGee H (2007) Health-Related Quality of Life in Cardiac Patients. In: Cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation, pp 256–268

Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA (2004) The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res 13(2):299–310

Hoekstra T, Jaarsma T, Veldhuisen DJ, Hillege HL, Sanderman R, Lesman-Leegte I (2013) Quality of life and survival in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 15(1):94–102

Iqbal J, Francis L, Reid J, Murray S, Denvir M (2010) Quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure and their carers: a 3-year follow-up study assessing hospitalization and mortality. Eur J Heart Fail 12(9):1002–1008

Zambroski CH, Moser DK, Bhat G, Ziegler C (2005) Impact of symptom prevalence and symptom burden on quality of life in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 4(3):198–206

Johansson P, Dahlström U, Broström A (2006) Factors and interventions influencing health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure: a review of the literature. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 5(1):5–15

Miller LW (2007) Heart transplantation: indications, outcome, and long-term complications. In: Cardiovascular medicine. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 1417–1441

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative S (2014) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 12(12):1495–1499

Farmer SA, Grady KL, Wang E, McGee EC Jr., Cotts WG, McCarthy PM (2013) Demographic, psychosocial, and behavioral factors associated with survival after heart transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg 95(3):876–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.11.041

Shamaskin AM, Rybarczyk BD, Wang E, White-Williams C, McGee E Jr., Cotts W, Grady KL (2012) Older patients (age 65+) report better quality of life, psychological adjustment, and adherence than younger patients 5 years after heart transplant: a multisite study. J Heart Lung Transplant 31(5):478–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2011.11.025

White-Williams C, Grady KL, Myers S, Naftel DC, Wang E, Bourge RC, Rybarczyk B (2013) The relationships among satisfaction with social support, quality of life, and survival 5 to 10 years after heart transplantation. J Cardiovasc Nurs 28(5):407–416. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182532672

Tseng PH, Wang SS, Chang CL, Shih FJ (2010) Job resumption status, hindering factors, and interpersonal relationship within post-heart transplant 1 to 4 years as perceived by heart transplant recipients in Taiwan: a between-method triangulation study. Transplant Proc 42(10):4247–4250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.09.063

Saeed I, Rogers C, Murday A (2008) Health-related quality of life after cardiac transplantation: results of a UK National Survey with Norm-based Comparisons. J Heart Lung Transpl 27(6):675–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2008.03.013

Delgado JF, Almenar L, Gonzalez-Vilchez F, Arizon JM, Gomez M, Fuente L, Brossa V, Fernandez J, Diaz B, Pascual D, Lage E, Sanz M, Manito N, Crespo-Leiro MG (2015) Health-related quality of life, social support, and caregiver burden between six and 120 months after heart transplantation: a Spanish multicenter cross-sectional study. Clin Transplant 29(9):771–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.12578

Galeone A, Kirsch M, Barreda E, Fernandez F, Vaissier E, Pavie A, Leprince P, Varnous S (2014) Clinical outcome and quality of life of patients surviving 20 years or longer after heart transplantation. Transpl Int 27(6):576–582

Kugler C, Tegtbur U, Gottlieb J, Bara C, Malehsa D, Dierich M, Simon A, Haverich A (2010) Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors after heart and lung transplantation: a prospective cohort study. Transplantation 90(4):451–457

Kugler C, Malehsa D, Tegtbur U, Guetzlaff E, Meyer AL, Bara C, Haverich A, Strueber M (2011) Health-related quality of life and exercise tolerance in recipients of heart transplants and left ventricular assist devices: a prospective, comparative study. J Heart Lung Transpl 30(2):204–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2010.08.030

Jakovljevic DG, McDiarmid A, Hallsworth K, Seferovic PM, Ninkovic VM, Parry G, Schueler S, Trenell MI, MacGowan GA (2014) Effect of left ventricular assist device implantation and heart transplantation on habitual physical activity and quality of life. Am J Cardiol 114(1):88–93

Holtzman S, Abbey SE, Stewart DE, Ross HJ (2010) Pain after heart transplantation: prevalence and implications for quality of life. Psychosomatics 51(3):230–236. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.51.3.230

Aguiar MI, Farias DR, Pinheiro ML, Chaves ES, Rolim IL, Almeida PC (2011) Quality of life of patients that had a heart transplant: application of Whoqol-Bref scale. Arq Bras Cardiol 96(1):60–68

Phan A, Ishak WW, Shen BJ, Fuess J, Philip K, Bresee C, Czer L, Schwarz ER (2010) Persistent sexual dysfunction impairs quality of life after cardiac transplantation. J Sex Med 7(8):2765–2773. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01854.x

Grandi S, Sirri L, Tossani E, Fava GA (2011) Psychological characterization of demoralization in the setting of heart transplantation. J Clin Psychiatry 72(5):648–654. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09m05191blu

Tung HH, Chen HL, Wei J, Tsay SL (2011) Predictors of quality of life in heart-transplant recipients in Taiwan. Heart Lung 40(4):320–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.11.003

Ruzyczka EW, Milaniak I, Przybylowski P, Wierzbicki K, Siwinska J, Hubner FK, Sadowski J (2011) Depression and quality of life in terms of personal resources in heart transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 43(8):3076–3081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.07.012

Kugler C, Bara C, von Waldthausen T, Einhorn I, Haastert B, Fegbeutel C, Haverich A (2014) Association of depression symptoms with quality of life and chronic artery vasculopathy: a cross-sectional study in heart transplant patients. J Psychosom Res 77(2):128–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.06.007

Sirri L, Magelli C, Grandi S (2011) Predictors of perceived social support in long-term survivors of cardiac transplant: the role of psychological distress, quality of life, demographic characteristics and clinical course. Psychol Health 26(1):77–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903377339

Trevizan FB, Miyazaki M, Silva YLW, Roque CMW (2017) Quality of life, depression, anxiety and coping strategies after heart transplantation. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 32(3):162–170. https://doi.org/10.21470/1678-9741-2017-0029

Milaniak I, Wilczek-Ruzyczka E, Przybylowski P, Wierzbicki K, Siwinska J, Sadowski J (2014) Psychological predictors (personal recourses) of quality of life for heart transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 46(8):2839–2843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.09.026

Jokinen JJ, Hammainen P, Lemstrom KB, Lommi J, Sipponen J, Harjula AL (2010) Association between gastrointestinal symptoms and health-related quality of life after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 29(12):1388–1394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2010.07.002

Segura-Saint-Gerons R, Segura-Saint-Gerons C, Alcantara-Luque R, Arizon-del Prado JM, Foronda-Garcia-Hidalgo C, Blanco-Hungria A (2012) Perceived influence of oral health upon quality of life in heart transplant patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 17(3):e409–e414

Riegel B, Moser DK, Carlson B, Deaton C, Armola R, Sethares K, Shively M, Evangelista L, Albert N (2003) Gender differences in quality of life are minimal in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail 9(1):42–48

Strömberg A, Mårtensson J (2003) Gender differences in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2(1):7–18

Conway A, Schadewaldt V, Clark R, Ski C, Thompson DR, Doering L (2013) The psychological experiences of adult heart transplant recipients: a systematic review and meta-summary of qualitative findings. Heart Lung 42(6):449–455

Baert A, De Smedt D, De Sutter J, De Bacquer D, Puddu PE, Clays E, Pardaens S (2018) Factors associated with health-related quality of life in stable ambulatory congestive heart failure patients: systematic review. Eur J Prev Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487318755795

Smith H, Taylor R, Mitchell A (2000) A comparison of four quality of life instruments in cardiac patients: SF-36, QLI, QLMI, and SEIQoL. Heart 84(4):390–394

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

E. Tackmann and S. Dettmer declare that they have no competing interests.

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Caption Electronic Supplementary Material

59_2018_4745_MOESM1_ESM.docx

The supplementary Table 1 provides further information on study design, enrolment criteria, instruments and limitations of the included studies.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tackmann, E., Dettmer, S. Health-related quality of life in adult heart-transplant recipients—a systematic review. Herz 45, 475–482 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-018-4745-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-018-4745-8