Abstract

Aim

The aim of the present study was to analyze whether there were changes in the severity of malocclusions of patients treated at the Department of Orthodontics, University of Giessen, Germany over a period of 20 years (1992–2012) and if the implementation of the KIG system (German index of treatment need) in 2001 had any effect on the patient cohort. Furthermore, the study aimed to analyze the influence of the severity of malocclusion on treatment quality and economic efficiency (relation payment per case/treatment effort).

Materials and methods

The files of all 5385 patients admitted to the orthodontic department between 1992 and 2012 were screened and the following information was recorded: patient characteristics, treatment duration, KIG, treatment outcome, and costs.

Results

In the KIG period, patients were older, pretreatment malocclusions were more severe, treatment took longer, required more appointments, and did not achieve the same degree of perfection as in the pre-KIG period. Patients with a higher pretreatment KIG category had longer treatments and did not achieve the same degree of perfection as patients with lower KIG categories. Although total payment was slightly higher for the more severe cases, their cost-per-appointment ratio was significantly lower.

Conclusion

In the present university department, a shift of the orthodontic care task towards more complex cases has occurred over the last 20 years. Generally the quality of orthodontic treatment was good, but it has been demonstrated that the higher KIG cases did not end up at the same level of excellence as the lower KIG cases. Furthermore, KIG 5 patients had a longer treatment duration, and required more appointments than lower KIG cases.

Zusammenfassung

Ziel

Ziel der vorliegenden Arbeit war es zu untersuchen, ob sich der Schweregrad der Malokklusionen von Patienten der Poliklinik für Kieferorthopädie der Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen über einen Zeitraum von 20 Jahren (1992–2012) verändert hat und ob die Einführung des KIG(Kieferorthopädische Indikationsgruppen)-Systems Einfluss auf die Patientenkohorte der Abteilung hatte. Des Weiteren wurde der Einfluss des Schweregrads der Malokklusion auf das Behandlungsergebnis und auf die Wirtschaftlichkeit der Abteilung (Verhältnis Einnahmen/Behandlungsaufwand) analysiert.

Material und Methoden

Die Akten von allen 5385 zwischen 1992 und 2012 aufgenommenen gesetzlich versicherten Patienten wurden untersucht. Analysiert wurden die Parameter Patientencharakteristika, Behandlungsdauer, KIG, Behandlungsergebnis und Kosten.

Ergebnisse

Nach Einführung des KIG-Systems waren die Patienten im Durchschnitt ein Jahr älter, hatten ausgeprägtere Malokklusionen und erreichten nicht die gleiche Perfektion im Behandlungsergebnis wie vor Einführung des KIG-Systems. Ferner fiel auf, dass Patienten mit hohem KIG (5) durchschnittlich eine 7 Monate längere Behandlungsdauer und 6 Kontrolltermine mehr hatten als KIG-3-Patienten. Generell waren die Behandlungsergebnisse gut, jedoch zeigte sich ein Zusammenhang zwischen dem Schweregrad der Malokklusion und der Ergebnisqualität. So erreichten beispielweise nur 51,4% der KIG-5-Fälle ein ausgezeichnetes oder gutes Ergebnis, während dies bei 65,6% der KIG-3-Patienten der Fall war. Zwar wurde die Behandlung von ausgeprägten Malokklusionen (KIG 5) durchschnittlich etwas höher vergütet, jedoch waren auch mehr Kontrolltermine nötig, sodass die Einnahmen-pro-Termin-Bilanz bei KIG-5-Fällen ungünstiger war als bei KIG-3-Patienten (74,92 vs. 82,21€/Termin).

Schlussfolgerung

In den vergangenen 20 Jahren hat eine Verschiebung des Patientengutes hin zu komplexeren Fällen stattgefunden. Patienten mit hohem Ausgangs-KIG-Wert erreichten nicht den gleichen Grad an Perfektion wie weniger komplexe Fälle, und ihre Therapie wurde in Relation zum Behandlungsaufwand geringer vergütet. Nach Einführung des KIG-Systems sind somit am untersuchten Standort negative Auswirkungen auf die Wirtschaftlichkeit der Abteilung entstanden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last few decades, advances in orthodontic and prophylactic measures, demographic changes, and patient demands as well as amendments in general healthcare policy have led to changes in orthodontic therapy [33]. These changes might have an impact on treatment expenditures and costs as well as on the quality of orthodontic care.

Different countries have developed diverging strategies concerning the financial coverage of orthodontic therapy. Whereas in some countries orthodontic treatment has to be paid for exclusively by the patients, other countries have developed systems of orthodontic treatment need, in which individuals with extreme malocclusions have the costs for therapy covered by the general health system. To be able to categorize a corresponding orthodontic treatment need, the German public healthcare system introduced the KIG (Kieferorthopädische Indikationsgruppen) in 2001 [16], which is based on the IOTN (Index of Treatment Need) [9]. Since implementation of this 5-score-index, clearly defined criteria have to be reached (score ≥3) for an orthodontic treatment to be covered by public health insurances.

From the perspective of the German general healthcare system, the implementation of the KIG can be considered successful, since a significant reduction of the number of patients undergoing orthodontic treatment at the cost of the public health insurances is evident [11, 17]. Also in Great Britain, political changes have had effects on the orthodontic profession. A recent study from St George’s Hospital Orthodontic Department reports that after the contract changes of the National Health Service there was an increase in the referrals of severe cases (high IOTN) from specialized practitioners to the clinic [21]. The authors assume that this change in referral practice is due to economic reasons, which implies that in specialized practices careful attention is given to an economically reasonable ratio of treatment effort to payment. Whether changes in the referral pattern to orthodontic departments of German universities have occurred since implementation of the KIG system has not yet been evaluated.

Aim

The aim of the present study was to analyze whether there were changes in the severity of malocclusions of patients treated at the Department of Orthodontics, University of Giessen, Germany over a period of 20 years (1992–2012) and if the implementation of the KIG system had any effect on the patient cohort. Furthermore, the study aimed to analyze the influence of the severity of malocclusion on treatment quality and economic efficiency (relation payment per case/treatment effort).

Materials and methods

The study was approved by the ethic committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Giessen, Germany (AZ.101/13). The files of all 5385 patients admitted to the orthodontic department between 1992 and 2012 were screened and those 3210 fulfilling the following inclusion criteria were included:

-

Complete records available

-

Orthodontic treatment in the department

-

Cost coverage by public health insurances

On the basis of the patients’ records the following information was recorded:

-

Pretreatment age

-

Gender

-

Dental stage (according to Björk et al. [8])

-

Active treatment duration

-

Number of appointments

-

Orthodontic appliances used

-

Removable only

-

Fixed only

-

Combination removable–fixed

-

Combination fixed–surgical

-

Others (e.g., chin cup, face mask)

-

-

KIG [16]

-

Treatment quality [1]

-

Treatment costs

Statistical analysis

An explorative statistical analysis of the data was performed in collaboration with the Institute for Medical Statistics of the University of Giessen, Germany using IBM SPSS 22. In addition to the descriptive assessment, the following tests were applied:

-

χ2 test to test for the independence of categorical data (treatment duration, dental stage, appliance type, KIG, treatment quality),

-

Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test to assess nonparametric independent samples for common features (i.e., age and treatment duration), and

-

Kruskal–Wallis test to test for group differences between nonparametric independent samples (i.e., payment and number of appointments related to KIG).

A total of 3210 patients were analyzed: 1273 were treated from 1992-2002 (before KIG implementation; “pre-KIG period”) and 1937 between 2002 and 2012 (after KIG implementation; “KIG period”).

Results

The mean age at the start of treatment was 12 ± 3.5 years. Comparing the two observation periods, it is striking that the median pretreatment age increased by approximately 1 year in the KIG period. No gender-specific differences concerning the pretreatment age were found (Table 1). For both observation periods the percentage of females was slightly higher than that of males (pre-KIG: 53.9% females, KIG: 54.6% females).

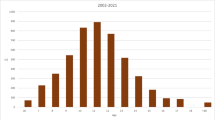

A total of 514 patients were treated in the early mixed or deciduous dentition, whereas the majority of patients (n = 2684) were treated in the late mixed or permanent dentition. When comparing the two observation periods, a significant reduction (p = 0.000) of the percentage of patients treated early was observed from the pre-KIG to KIG period (Table 2; Fig. 1).

Treatment duration

The median active treatment duration for the total subject material was 32 ± 17 months. On average, the active orthodontic therapy of boys took 2 months longer than that of girls (p = 0.035). Patients treated in the KIG period had a 7-month shorter treatment duration than patients treated in the pre-KIG period (p = 0.000). Patients with a severe treatment need (KIG = 5) had longer treatments than those with lower KIG scores (p = 0.000; Table 3).

In accordance with the active treatment duration, the number of appointments also increased with increasing KIG. For example, KIG 3 patients required a median of 28.4 ± 8 appointments, KIG 4 patients were seen 29 ± 8 times during their active treatment phase, and KIG 5 patients 34 ± 10 times (p = 0.002).

Orthodontic appliances

The majority of patients (64.6%) were treated exclusively with fixed appliances, whereby 17.5% had some time of removable appliance prior to multibracket therapy, 14.2% of the patients were treated with removable appliances only, and 3.5% were combined surgical–orthodontic cases. A small percentage (0.2%) was treated with extraoral appliances only. When comparing the two observation periods, it is striking that the percentage of patients treated exclusively with fixed appliances increased significantly after the KIG implementation. Whereas 50.7% of all patients treated in the pre-KIG period received only fixed appliances, this was the case for 73.7% of the orthodontic patients in the KIG period (p = 0.000).

KIG

Concerning the total subject material, the majority (n = 1885; 58.7%) had the malocclusion severity score KIG 4, followed by 548 patients (17.1%) with KIG 5 and 449 (14.0%) with KIG 3. Here a certain shift between the two observation periods can be noted, which shows a clear tendency towards more complex and less mild cases (KIG 1 and 2: −19%) treated after KIG implementation compared to the pre-KIG period (Fig. 2). By far the most frequent KIG category in both observation periods was “D” (increased overjet) with 26.8% of the patients before and 27.5% after KIG implementation (Fig. 3).

Treatment quality

Concerning the total subject material, 17.8% finished with an excellent treatment result according to the Ahlgren category, 40.2% were good, 34.4% were acceptable, and 7.6% were unacceptable. Once more, differences between the two time periods were striking, indicating more unacceptable results in patients treated in the KIG period (10.3%) compared to those in the pre-KIG period (4.4%; Fig. 4).

When relating the treatment outcome to the pretreatment malocclusion severity, it becomes evident that high-KIG patients were more likely to reach an unacceptable treatment result (KIG 5: 10.3% unacceptable) compared to KIG 1 or 2 patients, where only 3.1% fell into the category unacceptable (p = 0.001). Concentrating on the excellent treatment results, one finds 19.8% of the patients in the categories KIG 1 and 2 in this category, but only 12.7% of the KIG 5 patients (Fig. 5).

Payment

Of the present subject sample, reimbursement by the public health insurances was calculated from the files of 300 randomly selected patients, 100 each from the categories KIG 3, 4, and 5. These were all files from patients treated after 2004, as in 2004 an adjustment of the remuneration of orthodontic services by public reimbursement systems was launched, which is valid until today. The orthodontic department received a total of 2183.95€ (median) per patient from the public health insurances. This includes the price for laboratory procedures and materials. Treatment of KIG 5 patients was paid slightly more (median 2332.00€) than for KIG 3 (2097.52€) or KIG 4 patients (2155.55€; p = 0.039). Considering the reimbursement per appointment, however, KIG 5 patients had the lowest reimbursement per appointment with a median of 68.07€, compared to 74.24€ for the KIG 3 and 76.93€ for the KIG 4 patients (Table 4).

Discussion

This study analyzed a total of 3210 patients treated over a period of 20 years. Compared to similar studies in the literature [13, 14], this is quite a large sample, both in relation to the total number of patients and the time span. It can be assumed that the patient sample is representative for orthodontic departments at German universities. A recent paper from Saarland University described the KIG characteristics of 1766 orthodontic patients [26] and found the majority to be in the categories 4, followed by 5 and 3, with the subdivisions D (increased overjet), M (negative overjet), and K (crossbite), which is in accordance with the present patient cohort. It has to be noted, however, that our department has special expertise in Class II treatment, which explains the unusually high percentage of KIG D subdivision cases (26.8% in 1992–2002, 27.5% after 2002) for the present clinic site.

There has been a shift towards a later treatment start in the KIG period. This can be explained by the fact that—in accordance with the KIG guidelines—regular orthodontic treatment can only be carried out starting in the late mixed dentition, and only special KIG categories (e.g., syndromes, crossbites, overjet > 9 mm) are covered by the public health insurances at an earlier stage. Observational studies from other countries report even higher pretreatment ages at orthodontic university departments. In the United States, for example, average pretreatment ages of 16.6 years [14] or 15.3 years [12] are reported, which appears comparable to the average pretreatment age at Turkish universities (16.3 years [14]). In Japan, where Deguchi et al. [14] report about an average pretreatment age of 18.7, treatment is started even later. Traditionally, in Germany orthodontic treatment consisted of a high percentage of removable plates and/or removable functional appliance approaches. These appliances need time and patient compliance to achieve the required tissue reactions. With the privatization of the present university clinic in 2006, however, the economic pressure to achieve profit maximization increased tremendously. This resulted in a paradigm shift in the department towards a shorter treatment duration with fewer appointments. In turn, the required time/number of appointments to allow for removable functional appliances to work is simply no longer economically reasonable.

The average active treatment duration of the present patient sample was 32 months, with a strong impact of the pretreatment malocclusion severity. Whereas KIG 3 patients had a median of 28.4 ± 8 appointments in 29 months, KIG 4 patients required 29 ± 8 appointments in 32 months, and KIG 5 patients 34 ± 10 appointments in 35.7 months. Other authors also confirm that the treatment duration is influenced by the malocclusion severity [5, 28]. It is also reported that among others Class II malocclusions are correlated with a longer orthodontic therapy [15]. This bears a certain risk for bias, as a large percentage of patients in the present cohort were in the Class II KIG category (KIG = D3-5), since this, as mentioned before, is a special expertise of our clinic. However, when evaluating Class II patients treated with a Herbst appliance in our department, these are characterized by an extremely short median active treatment duration of 18 months [7]. Considering the fact that the present sample has a large percentage of Class II patients of which again a large percentage, especially in the high-KIG groups, received a Herbst appliance, the numbers have to be interpreted with care. Assuming that the KIG 4 or 5 Class II patients treated with a Herbst appliance have a similar short treatment duration as in the sample of Bock et al. [7], this would imply that treatment without a Herbst appliance in these KIG categories would take even longer. Thus, the situation for all other KIG groups (except subgroup “D”) is probably even more negative than it appears at first sight.

After implementation of the KIG system, more patients were treated exclusively with fixed appliances (73.7%) than in the earlier observation period (50.7%). This once more could be the result of an increasing demand for faster and more efficient orthodontic therapy, which is reached more reliably with fixed than with removable appliances [31, 32, 34]. This observation corresponds to the shorter treatment duration in the KIG (median = 27.0 months) compared to the pre-KIG period (median = 32.0 months).

Currently, there is limited information in the literature describing the distribution of KIG categories. This is due to the fact that this system is only applied in Germany. In one paper from another university center, all 1766 patients since the implementation of the KIG in 2002 were screened. Here a similar distribution as in the present sample was found with “D”, “M” and “K” being the most frequent KIG categories [26]. One major difference between the two universities, however, was that our department had significantly more Class II patients (n = 519 vs. 356), whereas they had many more craniofacial malformations (n = 245 vs. 74). The extreme accumulation of Class II patients in Giessen can be explained by the fact that Class II treatment with Herbst appliances is a focus of the department, whereas the accumulation of the craniofacial abnormalities in Homburg/Saar is probably due to their larger catchment area. Other studies evaluating KIG distributions have been performed on school children [3, 17, 18] or adults [6]. However, the comparability of the latter data to the present subject sample is limited, since we analyzed patients who actually underwent orthodontic treatment, implying that they had a need for therapy which the above cohorts did not necessarily have.

Treatment results

Compared to the pre-KIG period, the percentage of patients with unacceptable results increased remarkably (4.4–10%) after implementation of the KIG system. A correlation between the initial malocclusion severity and the treatment result was obvious. Whereas 10.3% of the KIG 5 patients achieved an unacceptable result, this was only the case for 3.1% of the KIG 1 and 2 patients. On the other hand, the KIG 1 and 2 patients achieved excellent results in 19.8% of the cases compared to only 12.7% of the KIG 5 patients. These results are in accordance with those of Cansunar and Uysal [13] who observed a direct correlation between the pretreatment case complexity and the treatment result when evaluating the orthodontic therapy of 1639 patients. Campbell et al. [12] also found that a good orthodontic treatment result in complex cases requires much more effort than in milder cases. Considering the fact that the total patient sample in the department has shifted from milder to more severe cases over the last 20 years, it is not surprising that the recent treatment outcomes were not as good as the earlier ones. Furthermore, as the trend is that both patients and parents are becoming more demanding, on the one hand, but less tolerant and compliant, on the other, it has to be considered that practitioners are placed under pressure by the patients and/or parents to finish treatment and remove orthodontic appliances as early as possible. This might additionally explain why cases are not treated to the same degree of perfection as earlier, despite advances in appliance technology and diagnostics.

Payment

The median total payment for a KIG 5 case was slightly higher (2332.00€) than for a KIG 4 (2155.55€) or 3 case (2097.52€). This is in accordance with other areas in general medicine were higher severity of illnesses also resulted in higher treatment costs, e.g., as reported for patients with burns [29] or pediatric intensive care [20]. However, in the present sample the price for laboratory procedures is already included. This means that the total payment is not the net income of the department, but also has to cover laboratory procedures. Considering now that more difficult cases often require more sophisticated appliances, which naturally are more expensive, the payment remaining for the department is often even lower than for a KIG 3 or 4 case. In addition, KIG 5 patients required much more treatment effort, which results in a better cost-per-appointment relationship for KIG 3 or 4 patients (74.24€ and 76.93€, respectively) compared to KIG 5 subjects (68.07€). Furthermore, the better treatment results of KIG 3 and 4 patients make the more complex cases even less appealing for the practitioner. From the economic perspective of a university clinic in the state of Hessen, Germany, this situation is particularly alarming as the reimbursement systems pay university dental clinics approximately 10% less than practitioners in private practices, irrespective of the malocclusion severity [24]. Additionally, considering the general inflation over the last 25 years, the total reimbursement for orthodontic treatment has been reduced by approximately 30% relative to the monetary value of 1991 [25]. This, of course, is in complete contradiction to the demand for more economic efficiency and profit maximization on behalf of the clinic management.

Summarizing, the percentage of severe orthodontic cases has increased significantly in the present department, their treatment takes longer, is reimbursed less per appointment, and does not achieve the same quality of result as less complex cases. This places academic orthodontic departments as ours into financial turmoil, as the situation makes it close to impossible to treat patients in the economic interest of the hospital. Again, a certain parallelism to other areas of medicine becomes evident where the reimbursement systems do not cover the full costs for treatment of severe cases. It is well known that university hospitals tend to treat more severe cases [2], but these specific circumstances of teaching hospitals are not considered when it comes to payment. Baumgart and le Claire [4] describe similar problems in the German DRG (Diagnosis-Related Group)-based reimbursement system for patients with inflammatory bowel disease, where expenditures were not fully covered by DRG proceeds. For the treatment of severe burns, insufficient cost coverage is also reported from authors of different DRG-based reimbursement systems [19, 22, 23, 27, 29] or for therapy for metastatic colorectal carcinoma [30]. Originally the implementation of the DRG system aimed to increase the efficiency of hospitals. The resulting side effects, however, are lower quality patient care, more readmissions and, naturally, a preference for more profitable cases [10]. Especially this preference for more profitable cases is comparable to the KIG distribution in orthodontic university departments where now more complex and, thus, less profitable cases accumulate. This in accordance with trends in the United Kingdom, where the contract changes of the National Health Service led to an increase in the referrals of severe cases (high IOTN) from specialized practitioners to the clinic [21].

Limitations

The numbers found in this study have to be interpreted with care, as the special focus of the department on Herbst/Class II therapy naturally leads to a certain degree of bias. Considering the fact that high KIG Class II cases (KIG 4 and 5) are those prone to receive a Herbst appliance and, thus, usually have a much shorter treatment duration than patients treated with other appliances, the significantly longer treatment duration for KIG 5 patients for all other categories except “D” is probably much more extreme than the numbers imply. In other words, we have to acknowledge that the financial burden of KIG 5 treatments is a much greater problem than assumed.

Conclusion

Within the limits of the present study, it has been shown that in the present university department a shift of the orthodontic care task towards more complex cases has occurred over the last 20 years. Generally, the quality of orthodontic treatment was good, but it has been demonstrated that the higher KIG cases did not achieve the same level of excellence as the lower KIG cases. Furthermore, KIG 5 patients had a longer treatment duration and required more appointments than low KIG cases. On the basis of this development it has to be stated that the implementation of the KIG system had a negative influence on the economic efficiency of the present university orthodontic department.

References

Ahlgren J (1988) Tiorårig utvärderin av ortodontiska behandlingsresultat. Tandlakartidningen 80:208–216

Allareddy V, Rampa S, Anamali S et al (2015) Obesity and its association with comorbidities and hospital charges among patients hospitalized for dental conditions. J Investig Clin Dent 9:1–8

Assimakopolou T (2004) Evaluierung der Prävalenzrate bei 9 bis 10-jährigen Probanden nach den Kieferorthopädischen Indikationsgruppen (KIG). Zahnmed Dissertation. Medizinische Fakultät der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster

Baumgart DC, le Claire M (2016) The expenditures for academic inpatient care of inflammatory bowel disease patients are almost double compared with average academic gastroenterology and hepatology cases and not fully recovered by Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) Proceeds. PLoS ONE 11(1):e0147364. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147364

Beckwith FR, Ackerman RJ Jr, Cobb CM et al (1999) An evaluation of factors affecting duration of orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 115:439–447

Bock JJ, Czarnota J, Hirsch C et al (2011) Orthodontic treatment need in a representative adult cohort. J Orofac Orthop 72:421–433

Bock NC, von Bremen J, Ruf S (2016) Stability of Class II fixed functional appliance therapy-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod 38:129–139

Björk A, Krebs A, Solow B (1964) Method for epidemiological registration of malocclusion. Acta Odont Scand 22:27–41

Brook PH, Shaw WC (1989) The development of an index of orthodontic treatment priority. Eur J Orthod 11:309–320

Busse R, Geissler A, Aaviksoo A et al (2013) Diagnosis related groups in Europe: moving towards transparency, efficiency, and quality in hospitals? BMJ 7(346):f3197

BZÄK/KZBV (2011) Daten & Fakten 2011

Campbell CL, Roberts WE, Hartsfield JK Jr et al (2007) Treatment outcomes in a graduate orthodontic clinic for cases defined by the American Board of Orthodontics malocclusion categories. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 132:822–829

Cansunar HA, Uysal T (2014) Relationship between pretreatment case complexity and orthodontic clinical outcomes determined by the American Board of Orthodontics criteria. Angle Orthod 84:974–979

Deguchi T, Honjo T, Fukunaga T et al (2005) Clinical assessment of orthodontic outcomes with the peer assessment rating, discrepancy index, objective grading system, and comprehensive clinical assessment. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 127:434–443

Fisher MA, Wenger RM, Hans MG (2010) Pretreatment characteristics associated with orthodontic treatment duration. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 137:178–186

Genzel H (2003) Richtlinien des Bundesausschusses der Zahnärzte und Krankenkassen für die kieferorthopädische Behandlung. Bundesanzeiger 226:24966

Glasl B, Ludwig B, Schopf P (2006) Prevalence and development of KIG-relevant symptoms in primary school students in Frankfurt am Main. J Orofac Orthop 67:414–423

Gottstein I, Borutta A (2007) Die Eignung der „Kieferorthopädischen Indikationsgruppen” (KIG) für die zahnärztliche Vorsorgeuntersuchung des Öffentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes (ÖGD). Gesundheitswesen 69:577–581

Holmes JH 4th (2008) Critical issues in burn care. J Burn Care Res 29(6 Suppl 2):180–187

Hsu BS, Brazelton TB 3rd (2015) A Comparison of Costs Between Medical and Surgical Patients in an Academic Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. WMJ 114(6):236–239

Izadi M, Gill DS, Naini FB (2010) Retrospective study to determine the change in referral pattern to St George’s Hospital Orthodontic Department before and after the 2006 NHS Dental Contract changes. Prim Dent Care 17:111–114

Kagan RJ, Edelman L, Solem L et al (2007) DRG 272: does it provide adequate burn center reimbursement for the care of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis? J Burn Care Res 28:669–674

Kagan RJ, Gamelli R, Saffle JR (2007) DRG 504: the effect of 96 hours of mechanical ventilation on resource utilization. J Burn Care Res 28:664–668

KZBV (2001) Änderung der Kieferorthopädie-Richtlinien des Bundesausschusses der Zahnärzte und Krankenkassen—Einführung des neuen Systems kieferorthopädischer Indikationsgruppen (KIG)

KZBV (2015) Jahrbuch. Statistische Basisdaten zur vertragszahnärztlichen Versorgung 85:162–166

Lisson J, Rijpstra C (2016) Die kieferorthopädischen Indikationsgruppen (KIG) und ihre Grenzen. Dtsch Zahnarztl Z 1:25–37

Lotter O, Jaminet P, Amr A et al (2011) Reimbursement of burns by DRG in four European countries: an analysis. Burns 37:1109–1116

Mavreas D, Athanasiou AE (2008) Factors affecting the duration of orthodontic treatment: a systematic review. Eur J Orthod 30:386–395

Mehra T, Koljonen V, Seifert B et al (2015) Total inpatient treatment costs in patients with severe burns: towards a more accurate reimbursement model. Swiss Med Wkly 24(145):w14217. doi:10.4414/smw.2015.14217

Mesti T, Boshkoska BM, Kos M et al (2015) The cost of systemic therapy for metastatic colorectal carcinoma in Slovenia: discrepancy analysis between cost and reimbursement. Radiol Oncol 49(2):200–208

Tang EL, Wei SH (1990) Assessing treatment effectiveness of removable and fixed orthodontic appliances with the occlusal index. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 98:550–556

von Bremen J, Pancherz H (2002) Efficiency of early and late Class II Division 1 treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 121(1):31–37

Wehrbein H, Wriedt S, Jung BA (2011) Change and innovation in orthodontics. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 54:1110–1115

Wiedel AP, Bondemark L (2015) Fixed versus removable orthodontic appliances to correct anterior crossbite in the mixed dentition—a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthod 37:123–127

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

J. von Bremen, E. M. Streckbein, and S. Ruf declare that they have no conflict of interest and did not receive financial support for this study.

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Dr. Julia von Bremen.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

von Bremen, J., Streckbein, E.M. & Ruf, S. Changes in university orthodontic care over a period of 20 years. J Orofac Orthop 78, 321–329 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-017-0088-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-017-0088-y