Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic shock has painted some unprecedented portrayal and presented some exceptional visuals regarding the economy vs. environment debate worldwide. The history of human civilization is impregnated with the exploitation of the environment. The world needs a long and clear vision where economic activities and developmental goals meet environmental sustainability. The fatal coronavirus and Covid-19 pandemic have already affected more than 216 countries worldwide, with more than thirty-six million confirmed cases, including millions of death tolls. Now, India has the second-largest number of Covid-19 affected confirmed cases. The pandemic-driven nationwide lockdown has had a fatal impact on the economy. The supply-side and demand-side for entire economic sectors were disrupted, industrial production has come to a halt, millions of jobs were lost, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was eroded away at an unprecedented rate, economic anxiety is inevitable in every sphere of life and livelihood. The GDP shows the last 20 years lowest in 2020. The impact of such an economic fallout is supposed to sustain for a long time with its deadly impact directly and indirectly. However, when we come to the environmental aspect, the lockdown exerts a very positive impact. The environmental pollution has been reduced remarkably, and the response in air quality, water quality, wildlife, and vegetation are remarkably flourishing. However, it would not be wise to blame the rampant economic activities and developmental initiatives for the present catastrophic situation. The economy must move on, industrial development would be geared up, and developmental projects must be initialized, but there should be a balance between economy and environment. Human civilization’s sustenance needs mutual harmony with the natural environment, and sustainable development is the safest avenue ahead.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Confusions, contradictions, and controversies have had been accustomed to sensible nexus between environment and economic development. Throughout the history of human civilization, the environment has had an inevitable fate of exploitation. The natural environment has a limited resilience to absorb and sustain against the small-scale exploitations. Every economic principle and mode of production exerts its impact on the environment with varying degrees across time and space. However, the emergence of capitalism and the industrial revolution had revolutionized the mode of environmental exploitation. When every part of nature and natural resources are being evaluated and targeted for capital gains, the exploitation becomes limitless, and the destruction becomes disproportionate. Several International Conventions and strategies are there to protect the environment, e.g., the Stockholm Declaration (1972), the World Conservation Strategy (1980), World Charter for Nature (1983), Brundtland Commission, Earth Summit Resolution, and declaration of Agenda-21 (1992), Malmo Declaration (2000), Rio + 10 and Rio + 20. However, all those global conventions declare the agendas, whereas environmental exploitation is continued in different shapes and various forms. Human civilization seems not in the mood to ‘stay.’ The ‘growth’ is felt like an extreme necessity and even at any environmental cost.

However, 2020 is the year when the entire world experiences the most common word of ‘lockdown’ in every sphere of life due to the fatal novel coronavirus attack. COVID-19 pandemic manifests worldwide. This malicious virus, which causes the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare the global pandemic, was first identified in Central China’s Wuhan province (Huang et al. 2020) in December 2019. India has the second-largest number of COVID-19 confirmed cases (6,685,082 confirmed), including 103,569 death as of October 6, 2020, 10:27 am CEST (WHO Coronavirus Disease Dashboard 2020). The first case of COVID-19 in India was reported from Kerala in March, 2020. For combating the rapid transmission of the coronavirus and resist the death toll, the nations worldwide followed a complete shutdown. India was not an exception. Following the voluntary Janta Curfew (public curfew) on March 22, 2020, the Indian Government declared a nationwide lockdown from 24 March midnight. The entire nation experienced a complete shutdown for 21 days, and it was extended up to May 3, 2020 in the second phase of the lockdown declared on April 15, 2020; followed by the third phase of lockdown from May 4 to May 17, 2020. With the third phase of the lockdown announcement, India’s Government divided all the districts into three zones based on the COVID-19 contamination character—‘green’ as least vulnerable, ‘orange’ as moderate, and ‘red’ as most vulnerable and some relaxations were announced accordingly. The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) further extended the lockdown from May 18 to May 31, 2020.

Moreover, the services have been started to resume in a phased manner vide Unlock 1.0 (June 1 to June 30, 2020), Unlock 2.0 (1 to July 31, 2020), Unlock 3.0 (1 to August 31, 2020), and Unlock 4.0 (1 to September 30, 2020). The usual flow of the world’s economy, calculation of global politics, sociocultural harmony, academic, environment, people’s normal lifestyle, everything has been drastically changed by the grasp of the life-threatening novel coronavirus, i.e., COVID-19 (Bera et al. 2020). Due to the lockdown, a drastic change in the weather pattern and pollutant parameter is witnessed.

2 Reinvigorating Environment

The COVID-19 pandemic driven nationwide lockdown heals the earth in a way never seen before. During the lockdown situation, humans are restrained from their routine activities. Nature started to readjust itself during the lockout condition, which had long been hampered due to pollution. India’s pollution level exceeds the standard limit, which was determined by national ambient air quality standards. It affects the health condition at a severe rate (Ghose et al. 2004) in the Indian population. A huge number of people have a respiratory problem due to high air pollution (Smith 2000). COVID-19 induced lockdown results a remarkable change in air pollution (Singh et al. 2020) worldwide. If we take the starting date of lockdown as a breakpoint and analyze the environment’s health during the lockdown and pre lockdown situation, the trend of pollution will be clear.

The monsoon climate dominates India. India experiences changes in temperature and rainfall trends due to global climate change, though the monsoon predominantly controls it. Different regions of India have faced a negative trend in rainfall during the last few decades. Patra et al. (2012) documented the negative trends in monthly, seasonal, and annual rainfall in the long term over Orissa. Praveen et al. (2020) analyzed the rainfall trend from 1901 to 2015 across India and observed an increasing trend during 1901–1950, while a declining rainfall trend was recorded after 1950 at an appreciable amount.

On the other hand, rising temperature trends have been observed (Fig. 4.1) in India. MERRA v2 data are used for assessing long term temperature trend analysis. The mean annual minimum temperature has been increased at 0.24 ℃ per 10 years over the Indian subcontinent (Rao et al. 2014). At the same time, the mean annual temperature was increased by about 0.4 degree Celsius per 100 years during 1901–1982 (Hingane et al. 1985).

The rapid urbanization and industrialization enhanced different pollutant levels considerably. The primary emission sources of Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) are transport, thermal power plants, and industries. Human exposure to NO2 over a short period causes infuriates asthma. On the other hand, the emission from industries and households contributes to PM2.5 and PM10 in the lower atmosphere. Such particulate matters do create some serious health hazards, including premature mortality, respiratory symptoms, bronchitis. Sulfur dioxide (SO2) is emitted mainly from coal-based thermal power plants and different industries. SO2 hampers the lung function and causes irritation to the eyes. Carbon dioxide (CO2) emission is dominated by the transport sector, biomass burning, and fuel combustion (Sharma and Dikshit 2016).

WHO (2005) reported that 7 million people died throughout the world due to air pollution. Epidemiological research for the last couple of decades pointed out that air pollution plays a crucial role in various respiratory diseases, which is the pivotal cause of premature mortality in developing countries like India. China and India combined contribute to 52% of total PM2.5 in the world, causing 1.525 million deaths in 2017 (Health Effects Institute 2019).

In general, the megacities of India used to face severe environmental problems due to heavy air pollution. The pollution levels surpassed the national air quality standards, as mentioned by the Central Pollution Control Board. Aerosols have caused serious human health issues. According to WHO’s EPI (Environmental Performance Index), Delhi is regarded as the most polluted megacity in the world. It has been reported that 1 out of every 8 deaths has been caused due to high air pollution in 2017 (ICMR, PHFI, and IHME 2017).

2.1 Environmental Resilience Amidst Lockdown

Lockdown as a measure for combating the virus prohibits mass transportation and all non-emergency economic activities. As the commercial, transport, industrial activities have been ceased almost for quite a long time, the environment finds its way to replenish itself and successfully stress out the burden of anthropogenic disturbances (Bera et al. 2020). In this regard, the release of GHG (Greenhouse gases), power generation, vehicular movement, coal combustion, and poisonous particulates emission have been truncated. It results in the quality enrichment of the global climate, pollution-free sky, and a vigorous resurgence of the Ozone (O3) layer (Chakraborty and Maity 2020). Lockdown becomes an amazing catalyst in reducing the energy consumption level. Fuel combustion drastically dropped down in the first half of 2020 as compared to preceding years. During the period of lockdown, emissions of hazardous gases put a break globally.

In the Yangtze River delta of China, the NO2, PM2.5, and SO2 have diminished (Li et al. 2020). Megacities of China experience a negligible concentration of pollutant gases amid lockdown (CAMS 2020) due to industrial activities confinement. Tobías et al. (2020) analyzed in detail that in the city of Barcelona (Spain), urban air pollution has diminished drastically just after two weeks of lockdown. PM10 concentration has a downfall by 28% for the traffic, and in the urban background stations, it has reduced by 31%. The Italian city of Milan witnesses a cut down of PM10 concentration during the partial lockdown phase and experiences a lowering by 13.1% during the total lockdown phase. A huge reduction (−57.6%) has been observed in the case of CO and NO2 emission in Milan (Collinvignarelli et al. 2020).

The suspension of industrial and commercial activities has lessened the pollution level in 88 cities of India (Sharma et al. 2020). A detailed study by Srivastava et al. (2020) at 34 monitoring stations in Delhi reveals an appreciable reduction in CO, NO2, PM2.5, and PM10 levels. The national air quality index reported an enormous improvement in air quality by 40–50%. Several studies (Maté et al. 2010) reveal that in Delhi, the average concentration of PM2.5 has been lowered down to 26 mg/m3 (on 27 March) from 91 mg/m3 (on 20 March) within a week of lockdown. An analysis by Mukhopadhyay (2009) spotlighted that in metropolitan Kolkata, 70% of people were victimized by lower atmospheric noxious pollutants. Global Carbon Project 2020 shows that the high emission rate of GHGs has been controlled in this period of lockdown, which is an unexpected phenomenon after World War II.

Worldwide lockdown works as a stimulus for revitalizing world climate. It gives ample opportunity for researchers to work in this unique direction. The present study focuses on the changes of atmospheric components like SO2, NO2, CO2, and aerosols in India during the lockdown period. Therefore, another focus of this study includes the impact of lockdown on the environment. The results of this study will be helpful in determining the fruitfulness of full lockdown as a strategy for diminishing air pollution.

The direct and indirect impacts of lockdown on atmospheric pollutants have been assessed using satellite-based spatio-temporal products related to NO2, CO2, SO2, and Aerosols. Carbon Dioxide, Mole Fraction in Free Troposphere, IR-Only (AIRX3C2Mv005, and AIRS3C2Mv005) products have been used to assess the scenario of CO2 concentration over India. The concentration of CO2 varies from 388.102 ppm to 392.737 ppm over India. The concentration of CO2 hotspots has been increased in the different parts of the Indian subcontinent over the last two decades (Fig. 4.2).

Aerosol optical depth 342.5 nm_0.25 deg product has been used to depict aerosol optical thickness in this study. Long-term trend of aerosol optical depth shows that it has been increasing over the sky of India. 5.2–7.4 unit was the dominant cover of aerosol, observed in India, but interestingly it has been suddenly started to fall in its thickness during the lockdown period (Fig. 4.3).

MERRA v2 product was used to portray the view of SO2 distribution. 1.80–2.68 kg/m2 was the long-term range of SO2 generally found in India. SO2 concentration in the Indian subcontinent has been remarkably started to decrease during lockdown (Fig. 4.4). OMI product has been used to show the NO2 distribution. NO2 is another bold atmospheric pollutant. Normal range of NO2 was −2.0921e + 014 to 1.44568e + 016 mol/cm2, generally found in India. However, during the lockdown, it has also been started to confine its arm over India’s sky (Fig. 4.5).

2.2 Inhale Afresh Amidst a Gasping Economy

Anthropogenic encroachment in the environment teaches us how far we are responsible for our own destruction. The deteriorated air quality hampers the natural rhythm of the environment and obliges to turn down human health. It has been reported that acute air pollution brings death toll across the globe in the form of respiratory diseases (26%), stroke and ischemic heart (17%), chronic pulmonary disease (WHO 2020). It is documented that 1.1 billion populations worldwide are forced to inhale toxic air (UNEP 2002).

Fortunately (from an environment perspective), global lockdown helps to rejuvenate the air quality. It positively affects the global climate by deducting the concentration of pollutants. The fatal virus threatens our life on one hand and gives the environment a chance to restore itself. So, the global perturbation about air pollution gives ample opportunities to scrutinize over the burning issues amidst the pandemic (Shehzad et al. 2020). Several studies reveal the reduction of pollutants level throughout the globe. A study conducted by Cadotte (2020) reveals the fact that air pollutants level has been diminished in major cities during the lockdown. NO2 is reduced by 30% and carbon emission by 25% in China (Liu et al. 2015 ) during this phase. Analysis of Watts and Kommenda (2020), Coccia (2020), and Ogen (2020) also documented the same fact of reduction of air pollutants. The concentration of NO2 has decreased by 12.1% between 1 and March 21, 2020; while in 2019, an increase was detected of NO2 concentration by 0.8% during the same period (Biswal et al. 2020). COVID-19 induced lockdown has an awe-inspiring impact on the environment. The restricted human actions have offered nature, wildlife, and the natural ecosystem an excellent opportunity to move, flourish, and replenish. However, for a wider section of the population, the lockdown becomes a nightmare, putting a halt to their jobs. The country is in a perpetual debate, which the next section will focus.

3 Turbulence in Economy

COVID-19 pandemic has misstruck the economy with varying degrees of impact across space and sectors. The pandemic’s impact on the economy must be addressed considering the pre-COVID pandemic economy, the preparedness and resilience of the economy to fight against the shock of slowing down, and the measures taken during the pandemic situation. The analysis of the Indian economy amidst the pandemic ambiance should be judged with the prelude that the GDP growth has been exhibiting a decelerated trend since 2015–2016 in the country. An inquisitive reader must be knowing that GDP is the final value of the product and services produced within the geographic boundaries of a state for a specified time interval. The nationwide lockdown costs havoc for the Indian economy, including its twenty-nine states and seven union territories. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is evident for the entire nation. However, the degree of impact has had varying magnitude across the states, depending on their economic structure, sectoral composition, and workforce.

3.1 Pre-lockdown Economy: Was It Tranquil?

Let us concentrate on just a few years back—India’s economic scenario clearly tells about the economic slowdown that has been considered a political debate rather than an economic in media houses. India’s position as one of the fastest-growing economies from 2014–2017 in the world arena slips in 2018–2019 with reducing GDP growth rate. The indicators of national economic health in the form of GDP, Index for Industrial Production (IIP), investment rates, exports, imports, and government revenues ring the alarm bell (Fig. 4.6).

(Source CEIC [CEIC Indicator dashboard is available under the URL: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicators] for a, b, and c; The Trading Economics Portal [Trading Economics Portal: https://tradingeconomics.com/] and Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Govt. of India for d, e, and f)

(a) India industrial production index growth, 2006–2020; (b) India GDP growth rate, 2010–2019; (c) Growth in investment in India, 2010–2020; (d) India export status, 2010–2020; (e) India import status, 2010–2020; (f) Growth of govt. revenue in India, 2010–2020

India’s index for industrial production growth (Fig. 4.6a) has been denying a stable growth trend since 2011–2012, and in 2018 it declined sharply. The declining trend in the economy’s output and fall in production affected employment and income. India’s GDP growth (Fig. 4.6b) has been continuously declining since 2016, whereas the investment rate also shows a reducing trend in investment in terms of the percentage of GDP since 2014. However, the export and import curve (Fig. 4.6d, e) express a healthier scenario comparatively, and the government revenue collection (Fig. 4.6f) gives some hope with its steady growth since 2010. There are several global and structural factors behind this economic turmoil, which include the very debated and controversial ‘demonetization,’ GST implementation and reforms in the taxation process in India, and so on since 2016. The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) sparked the great recession worldwide and cost the economy worldwide. India was not an exception. The global demand and prices were reduced, which costs the export and investment in India severely. The corporates and small to large-scale companies were experiencing an environment of low demand, high-interest rate, the higher exchange rate of Indian currency, and slow growth that make them very difficult to pay the credit to the bank that was promised during the boom.

Decreasing the repayment capability of corporates leads to India’s Twin Balance Sheet problem. Reserve Bank of India (RBI) data shows the steady rise of non-performing assets (NFAs) since 2011 and a steep rise since 2015 with the highest peak in 2018. Due to capital infusion by the Govt. of India the NPAs ratio (Fig. 4.7) has shown a recovery in 2019 but still it stands at around 9% level. High magnitude frauds also contribute to the NFAs that limits the bank’s offer to new emerging small enterprises with more ease. The increasing proportion of the non-performing assets (NFAs) severely affects the bank’s capacity to grant further credit and lend. In December 2016, RBI introduced the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) as a recovery measure to NPAs, but it raises complexity. Despite this economic volatility and structural issues, the global oil price fall. An increase in the global demand and depreciation of the Indian rupee contributes some ray of hopes to the Indian economy. Diminishing consumer demand and lacking private investments are the key factors that affect economic growth. Moreover, the agricultural sector has been going through a battle against climate change and drought conditions in major parts of the country since 2014. With the demonetization, most of the savings for rural and small-scale enterprises have been taken away. In this overall crisis period with diminishing investment both in formal and informal sectors, the economic slowdown was inevitable (Kotwal and Sen 2020). All these things manifest the pre-conditions in the Indian economy on which the surge.

3.2 COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Economy

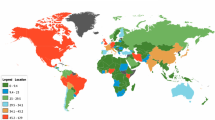

It’s lockdown! No movement, no business, no sell! The production exchange, and consumption of all kinds of goods and services, except few extreme essentials, have been restricted due to an unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic situation. The worldwide COVID-19 pandemic affects the world economy badly. India is going through an extremely critical and crisis period in terms of economy and public health. The unemployment rate has sharply escalated during 2020 (Fig. 4.8b). The GDP shows the last 20 years lowest in 2020, slides from 5.02% in 2019 (Fig. 4.8a). The decelerated GDP rate must affect its three contributing components: consumption, investment, and external trade. The GDP share of different economic sectors is unique and unequal (Fig. 4.9) that may lead to variable degrees of pandemic impact on different economic sectors (Table 4.1). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is noticeable, but its severity varies across economic sectors and spaces. Indian economy is diverse, and the sectoral structure varies from state to state. The state-wise number of factories (Fig. 4.10) and the poverty condition (Fig. 4.11) has been taken to represent the pre-pandemic economic condition. Apart from this, the Gross State Domestic Production (GSDP) by different Indian states clearly shows the spatial inequality. The Indian states’ GSDP share and state-wise COVID-19 status indicate that the ‘sound’ economy is affected most (Fig. 4.12). The GSDP share from different sectors is hugely different for different states (Fig. 4.13), and the states with greater dependency on industry, manufacture, and services have faced more severe impacts. In contrast, the states with more agriculture dependency are in comparatively stable economic conditions. Various states in India contribute to the economic growth of India in the manufacturing sector. However, five states: Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Gujrat, Uttar Pradesh, and Andhra Pradesh collectively hold around 53% of India’s total factories (Fig. 4.10).

(Source The Trading Economics Portal & Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy CMIE [CMIE data portal on unemployment, URL: https://unemploymentinindia.cmie.com/])

(a) GDP growth rate from 2000–2020 (b) India unemployment rate 2018–2010

(Source The Trading Economics Portal [Trading Economics Portal: https://tradingeconomics.com/] and Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India datasets)

GDP from (a) agriculture; (b) manufacturing, and (c) construction

The state-wise COVID-19 epidemic data reveals that Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Delhi, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka are mostly affected (Fig. 4.13), followed by Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, and Kerala. The demand-supply chain was disrupted by prolonged lockdown across the country and restrictions imposed on exchange globally.

3.3 Disruption in the Demand Side

Prolonged lockdown accelerates a situation of less transaction both in rural and urban areas, and it limits the desire of investment in non-essential goods and services by common people. Due to prolonged lockdown, non-regularity in banking transactions, uncertainty in job security across economic sectors limits the available cash in hand for common people. However, there is a decline and limited tendency to move outside in unlocking phases because of restrictions and risk of infection. Despite unlocking phases, there are also the provision of containment zones and a long way to wait for normalcy. This situation could lead to a sharp decline in the demand-side for non-essential investment and everyday life essential.

3.4 Stagnation in the Supply-Side

Major import partners for India are China (16% of total imports), the United States (6% of total imports), United Arab Emirates (6% of total imports), Saudi Arabia (5% of total imports), and Switzerland (5% of total imports).Footnote 1 China’s Wuhan is the hot spot from where the deadly coronavirus has been outspread to the 188 countries with more than 31.6 million cases as of 23 September 2020. The USA is the worst affected nation with around 2 lakh deaths, and more than 6,800,000 confirmed cases due to COVID-19 pandemic. In this context, entry bans, the imposition of quarantine, restricted international exchange, the supply chain has totally disrupted. Besides, the India–China international border tension contributes more complexities in India–China trade relations. Electrical machinery and equipment, plastic, organic chemicals, fertilizers, machinery, and nuclear reactors are the commodities imported from China with the highest share. In 2019 India imported 60.9% of its total import from Asian countries and 15.9% of its purchase by value from European partners, followed by 9.2 and 8.1% supplied by North America and African countries. The sudden collapse of international import would have cost havoc to the Indian manufacturing economy and the supply side. The industries which mostly depend on foreign imported raw material are struggling very hard. The supply chain is also interrupted by huge reverse migration of migrant labourers to their native places, the containment zone restriction within states, irregular transport services, and numbers of masked factors. Labor intensive economic sectors face an unprecedented situation.

3.5 Persuading the Policies to Ground Realities

The worldwide economy, including the Indian economy, has been facing an unprecedented situation that has revolutionized the ongoing system in every sphere of life and livelihood. There is an ongoing debate on the advantage and disadvantages between the ethos of ‘Capitalism’ and ‘Socialism’—specifically, their guided mode of production and distribution system to cope with this crisis. However, evidently, both the systems have been affected depending on their effective preparedness, resilience, and exposure.

Analyzing the sector-wise impact of COVID-19 and the pandemic status across the states in India, it might be said that the North-Eastern states in India are in the least degree of risk. This is mostly because of their relative isolation in terms of different aspects of life and livelihood in comparison to the western and southern states. The lower GSDP share (Fig. 4.13), least market defined economic opportunities, and less exchange and movement have reduced the risk of rapid infection as well as the economy. The people of these states are comparatively more sensitive and conservative towards their society, culture, and traditions and, most importantly, have less exchange with the outside world. These factors contribute to some optimistic scenarios regarding the spread of the coronavirus in these locations. The agricultural sector is more resilient and shows stability with relatively less affected GDP share than industry, manufacture, and service. So, the states with greater dependence on the agricultural sector have a better opportunity to revive.

However, the western and southern part states, such as Maharashtra, Gujrat, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, are more dynamic and produce relatively high GSDP (Fig. 4.14) with more dependence on manufacture, industry, and service sector economy are affected most. Due to the suspension of activities contributing to industry, manufacture, and service, a vast number of migrants who were stranded outside their native places primarily have started to back home in different phases through different modes of transport even the country has witnessed the returning of migrant labor walking thousands of miles. The reverse migration would have a tremendous impact not only on demography but also on the economy. The interstate migration pattern in India varies across states and is mostly guided by their economy. The 2011 census data clearly shows that whereas Maharashtra, Delhi, and Gujrat are the largest receivers of interstate migrants, the state of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar have disproportionately largest number of out-migrants with 37% of total inter-state migrants (Chandramouli et al. 2011). The states of UP, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan collectively contribute around 505 of total inter-state migration (Chandramouli et al. 2011). The inter-state migration flow was reported to increase 45% from 2001 to 2011 (Chandramouli et al. 2011). It is obvious that on the verge of 2020, the flow must be increased at a large number. Hence, reverse migration hits havoc the manufacture, industry, and service sector, whereas the in-migration in the recipient states greatly face undue pressure on economic structure.

But the crisis must provoke some opportunities. With the phase-wise unlock periods, the economy has been trying to get back in its path. Indian Govt. has already declared the Self-reliant India Initiative (Atmanirvar Bharat Abhiyan) package of twenty thousand crores with some key relief announcements for various economic sectors and practical initiatives to boost up the global supply chain in various sectors, reforms in several sectors, and relaxation in foreign investment rules. Most importantly, to make the country self-reliant, the Centre–state relation has to be redefined to make the state as self-sustaining economic territories in terms of energy, economy, food production, water, and environment. All the policy decisions must focus on more distribution principles rather than a concentrated focus toward the Centre. The way ahead of the pandemic era demands the federal economy in real sense along with good governance and smart fiscal discipline.

4 Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has actually painted and presented some impossible scenarios in various aspects of life and livelihood. Whereas the natural environment has got a very positive impetus, but the economy and livelihood have been affected very badly. Millions of jobs have been lost; employment generation has been slowed down, shortage of available cash in hand has made serious constraints on the demand side, and the total production and distribution system has been paralyzed, leading to an unprecedented recession since the 1930s’ great depression in the world economy. However, long-time mass confinement due to the nationwide lockdown has also reduced the atmosphere’s pollutant concentration. A restricted mass movement, closure of industries, and drastic reduction of fossil fuel consumption make the natural environment purer to live, breathe, and sustain not only for humans but also for every species and wildlife on the planetary earth. The economy must move on; development must be targeted, but human civilization has to make some balance between environment and development, and the only way is ‘sustainability’. Unfortunately, there is an immense probability of environmental exploitation in the post-COVID-19 pandemic situation. It shall not be wise to adulterate environmental safeguards and protection regulations to revive the economy and gear up the developmental works. The PARIVESHFootnote 2 portal data clearly shows that the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change (MoEFCC) of India has approved 2604 proposals (85.6%) out of 3042 proposals submitted between July and October (October 7, 2020) for environment clearance, and it is highly alarming. Interference in bio-diversity hotspot areas around protected areas and wildlife sanctuaries should not be tolerated at any cost or for the sake of the developmental project. Being a developing nation, India has a huge burden and responsibility to flourish immense economic and developmental opportunities through significant investment in industry, manufacture, and service. However, at the same time, India also has the responsibility to balance competing needs. The very principles of sustainable development are the only way to follow and reestablish the man–environment nexus to sustain human civilization.

References

Annual Report, 2019–20, Ministry of Mines, Govt. of India. https://mines.gov.in/ViewData/index?mid=1385. Accessed 26 Sept 2020

Bera B, Bhattacharjee S, Shit PK, Sengupta N, Saha S (2020) Significant impacts of COVID-19 lockdown on urban air pollution in Kolkata (India) and amelioration of environmental health. Environ Develop Sustain:1–28

Biswal A, Singh T, Singh V, Ravindra K, Mor S (2020) COVID-19 lockdown and its impact on tropospheric NO2 concentrations over India using satellite-based data. Heliyon 6(9):e04764

Cadotte M (2020) Early evidence that COVID-19 government policies reduce urban air pollution

Chakraborty I, Maity P (2020) COVID-19 outbreak: migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Sci Total Environ:138882

Chandramouli C, General R (2011) Census of india 2011. Provisional Population Totals. Government of India, New Delhi, pp 409–413

Coccia M (2020) The effects of atmospheric stability with low wind speed and of air pollution on the accelerated transmission dynamics of COVID-19. Int J Environ Stud:1–27

Collivignarelli MC, Abbà A, Bertanza G, Pedrazzani R, Ricciardi P, Miino MC (2020) Lockdown for CoViD-2019 in Milan: what are the effects on air quality? Sci Total Environ 732:139280

Ghose MK, Paul R, Banerjee SK (2004) Assessment of the impacts of vehicular emissions on urban air quality and its management in Indian context: the case of Kolkata (Calcutta). Environ Sci Policy 7(4):345–351

Health Effects Institute (2019) State of Global Air 2019. Special report. Health Effects Institute, Boston

Hingane LS, Rupa Kumar K, Ramana Murty BV (1985) Long-term trends of surface air temperature in India. J Climatol 5(5):521–528

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y et al (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395:497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5

ICMR, PHFI, IHME (2017) India: health of the nation’s states-the India state-level disease burden initiative. Indian Council of Medical Research, Public Health Foundation of India, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, New Delhi

Kotwal A, Sen P (2020). What should we do about the indian economy? Accessed from https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/what-should-we-do-about-indian-economy

KPMG Report on Impact of COVID-19 on the mining sector in India, May (2020) https://home.kpmg/

Li L, Li Q, Huang L, Wang Q, Zhu A, Xu J, ... Chan A (2020) Air quality changes during the COVID-19 lockdown over the Yangtze River Delta Region: an insight into the impact of human activity pattern changes on air pollution variation. Sci Total Environ 732:139282

Liu C, Hsu PC, Lee HW, Ye M, Zheng G, Liu N, … Cui Y (2015). Transparent air filter for high-efficiency PM 2.5 capture. Nat Commun 6(1):1–9

Maté T, Guaita R, Pichiule M, Linares C, Díaz J (2010) Short-term effect of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) on daily mortality due to diseases of the circulatory system in Madrid (Spain). Sci Total Environ 408(23):5750–5757

Mukhopadhyay K (2009) Air pollution in India and its impact on the health of different income groups. Nova Science Publishers, New York

NSSO Report (2016) 73rd round of national sample survey. http://www.mospi.nic.in/https://www.ibef.org/industry/oil-gas-india.aspx#:~:text=The%20oil%20and%20gas%20sector%20is%20among%20the,adopted%20several%20policies%20to%20fulfil%20the%20increasing%20demand. Accessed 27 Sept 2020

Ogen Y (2020) Assessing nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels as a contributing factor to the coronavirus (COVID-19) fatality rate. Sci Total Environ:138605

Patra JP, Mishra A, Singh R, Raghuwanshi NS (2012) Detecting rainfall trends in twentieth century (1871–2006) over Orissa State. India Clim Change 111:801–817

Praveen B, Talukdar S, Mahato S, Mondal J, Sharma P, Islam ARMT, Rahman A (2020) Analyzing trend and forecasting of rainfall changes in india using non-parametrical and machine learning approaches. Sci Rep 10(1):1–21

Rao BB, Chowdary PS, Sandeep VM, Rao VUM, Venkateswarlu B (2014) Rising minimum temperature trends over India in recent decades: implications for agricultural production. Global Planet Change 117:1–8

Sharma M, Dikshit O (2016) Comprehensive study on air pollution and green house gases (GHGs) in Delhi. A report submitted to Government of NCT Delhi and DPCC Delhi, pp 1–334

Sharma M, Jain S, Lamba BY (2020) Epigrammatic study on the effect of lockdown amid Covid-19 pandemic on air quality of most polluted cities of Rajasthan (India). Air Qual Atmos Health:1–9

Shehzad K, Sarfraz M, Shah SGM (2020) The impact of COVID-19 as a necessary evil on air pollution in India during the lockdown. Environ Pollut 266:115080

Singh V, Singh S, Biswal A, Kesarkar AP, Mor S, Ravindra K (2020) Diurnal and temporal changes in air pollution during COVID-19 strict lockdown over different regions of India. Environ Pollut. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115368

Smith KR (2000) National burden of disease in India from indoor air pollution. Proc Natl Acad Sci 97(24):13286–13293

Srivastava S, Kumar A, Bauddh K, Gautam AS, Kumar S (2020) 21-Day lockdown in India dramatically reduced air pollution indices in Lucknow and New Delhi, India. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 105:9–17

Tobías A, Carnerero C, Reche C, Massagué J, Via M, Minguillón MC, … Querol X (2020) Changes in air quality during the lockdown in Barcelona (Spain) one month into the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. Sci Total Environ:138540

Tourism and Hospitality sector overview, Invest India website. Accessed 24 Sept 2020. https://www.investindia.gov.in/

Tripathi B (2018) Now, India is the third largest electricity producer ahead of Russia, Japan. Business Standard India, 26 March. Accessed 27 Sept 2019

UNEP (2002) Environmental threats to children: children in the New Millennium. United Nations Environmental Programme, UNICEF, WHO. https://www.who.int/watersanitationhealth/hygiene/settings/ChildrenNM7.pdf?ua=1

Watts J, Kommenda N (2020) Coronavirus pandemic leading to huge drop in air pollution

WHO (2005) WHO Air quality guidelines for particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide: global update 2005: summary of risk assessment (No. WHO/SDE/PHE/OEH/06.02)

WHO (2020) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) situation reports. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Accessed 30 Apr 2020

Web Sources

http://vibrantgujarat.com/writereaddata/images/pdf/chemical-and-petrochemical-sector.pdf. Accessed 25 Sept 2020

http://ficci.in/sector.asp?sectorid=33. Retail Sector overview. Accessed 25 Sept 2020

https://www.ibef.org/industry/education-sector-india.aspx. Accessed 26 Sept 2020

https://www.ibef.org/industry/agriculture-india.aspx Accessed 26 Sept 2020

https://www.ibef.org/industry/healthcare-india.aspx. Accessed 26 Sept 2020

http://www.social.niti.gov.in/health-index. Accessed 26 Sept 2020

https://www.investindia.gov.in/sector/pharmaceuticals. Accessed 27 Sept 2020

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electricity_sector_in_India. Accessed 27 Sept 2020

https://www.investindia.gov.in/sector/telecom. Accessed 28 Sept 2020

https://parivesh.nic.in/. Accessed 7 Oct 2020

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sarkar, T., Mondal, J. (2021). Boon for the Environment and Bane for the Economy: Emerging Debate in Pandemic Stuck India. In: Mishra, M., Singh, R.B. (eds) COVID-19 Pandemic Trajectory in the Developing World. Advances in Geographical and Environmental Sciences. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-6440-0_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-6440-0_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-33-6439-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-33-6440-0

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)