Abstract

Whilst the notion of school-university partnerships is not new, in locations such as New South Wales (NSW), Australia, there has been a renewed interest in consolidating these partnerships in order to develop sustainable mutually beneficial relationships. In recognition of rising tensions between universities as Initial Teacher Education providers (ITE) and schoolteachers as supervisors of pre-service teachers (PST) whilst on professional experience placements, the NSW Department of Education initiated the HUB schools initiative. The initiative aimed to identify school sites that were actively engaged in the PST supervision process and link them with a partner university to support the codesign and development of more effective boundary crossing projects that met the needs of both stakeholders. The initial iteration of the program provided the opportunity for twenty-four schools across the state to partner with a university with varying levels of engagement and tangible outcomes. This chapter will trace the development of the initiative and then explore the value of the role of the school-based Professional Experience Coordinator (PEXC) as an integral piece in a school and university relationship.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

3.1 Introduction

In this chapter, we acknowledge that the notion of the school-university partnership is not new and is supported by a growing body of literature both internationally and in Australia. However, whilst the concept of professional experience in higher education has been well researched (Green et al., 2020; Le Cornu, 2016; Moss, 2008), the literature does not necessarily reflect on the emerging area of partner-driven Work Integrated Learning (WIL) inclusive of university and school stakeholder collaboration (Loughland & Ryan, 2020). This has the potential to not only identify change mechanisms that can directly influence policy and practice but codesign the process of teacher education. Tangible partnerships between universities as teacher education providers and schools in the development of pre-service teachers provide an increased level of authenticity and relevance to the work of each stakeholder group in regard to their role and shared vision in the preparation of future teachers (Loughland & Nguyen, 2020).

Teacher education professional experience (PEx) programs are a space where theory and practice intersect and a site for tensions between stakeholders, such as universities and schools who may have differences in expectations for these experiences (Zeichner, 2010). It was this space, and perceived tensions in regard to expectations, that prompted a reimagining of partnerships between the New South Wales Department of Education (NSW DoE) and universities. The aim was to support both sets of stakeholders to work in a more collaborative way in order to develop more efficient preparation programs with increased levels of support for PSTs whilst they transition into the classroom. These reimagined partnerships were formed under the umbrella of the HUB schools initiative. This chapter will explore the HUB school model with a specific focus on the role of the school-based Professional Experience Coordinator (PEXC) as a legitimate boundary crosser (Akkerman & Bakker, 2011) and critical link to successful pre-service teacher (PST) engagement in the space that exists between partners. The chapter will unpack the perceived efficacy, impact, and status associated with the PEXC role and discuss the time, resourcing, and responsibilities that underpin this key role in driving successful professional WIL placements.

3.2 Background

University-based initial teacher education (ITE) programs have come under criticism from schoolteachers for being detached from the daily operational needs of schools and being more aligned with pedagogical theory instead of authentic skills (Clarke & Winslade, 2019). Historically, there have been tensions around the notion of “whose knowledge counts” when it comes to what should be taught in teacher education training courses (Zeichner, 2018). These tensions have been heightened, for ITE students when they are required to move from the theoretical lecture room of the university into school classrooms and the practical reality of professional experience (Green et al., 2020; Zeichner, 2010). This tension between universities and schools can impact the collaborative development of teaching practicums designed to produce profession ready graduates amidst a chronic teacher shortage across Australia.

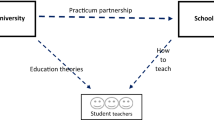

There is a growing literature on the opportunities that school-university partnerships can afford (Smith, 2016; Winslade et al., 2021). Successful school-university partnerships provide the opportunity to bring together two disparate cultures to create an environment where ITE students can experience the best of both worlds in a synchronised theory/practical environment conducive to successful student transition into the classroom (Moran et al., 2009; Zeichner, 2021). For universities, a partnership approach provides a genuine opportunity to change the way they view schools from a site that provides placements or as a source of potential research data towards being strategic partners engaged in course and subject design and delivery. For schools, there is an opportunity to benefit from the expertise of universities in generating rigorous evidence to support the development of professional learning materials. For most partnerships, the challenge is how to more actively engage both partners in the process of bringing theory and practice together for the common goal of the preparation and supervision of PEx placements.

3.3 ITE Professional Experience—An Enduring Challenge

Professional experience has been positioned as a challenging part of ITE preparation. The challenge is attributed to a range of factors including political agendas, cultural differences, and the challenging operational environment that schools often find themselves in (Grima-Farrell et al., 2019). Unfortunately, it has been noted that these challenges can limit the potential value of professional experience to another mandatory, albeit high stakes, course assessment rather than an opportunity for professional learning (Ingvarsson et al., 2014).

As mentioned, criticism of university-led ITE programs has been noted not just in Australia but around the world (Darling-Hammond, 2010) with concerns around the perceived ad hoc nature of universities’ approach to and facilitation of placements. Issues such as time pressure, calendar and timetabling constraints, the perceived oversupply of ITE students as pre-service teachers, and subsequent demands on schools including a lack of appropriately qualified supervising teachers in hard-to-staff discipline and regional locations have all been identified as contributing to the complexity of PEx. Underpinning this study and the push for reimaging partnerships were the findings of such reports as the Top of the Class: report on the enquiry into teacher education (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Education and Vocational Training, 2007). This report highlighted concerns around perceived weaknesses in the way the current system linked theory and practice. These included the perception of a lack of relevance that exists in some aspects of teacher education courses including the ability of both pre and beginning teachers to cope with behavioural issues and classroom management concerns, reporting, and communication with the wider community.

3.4 School-University Partnership Elements of Success

Successful partnerships are underpinned by a clear understanding of the elements that contribute to partnership efficacy. This understanding is supported by a growing amount of international literature around effective implementation and sustainability of partnerships. Despite the diversity evident across various partnership models, a number of key commonalities appear worldwide. These include the level of value aligned to sustained relationships, acknowledgement, and mitigation of perceived imbalances that may exist in the space between both university and school operations and cultures, the role of leadership, communication, ability to implement a staged approach, shared vision, incentives, and the significance of an effective boundary crosser (Akkerman & Bakker, 2011). Sound, sustained relationships enhance the effectiveness of school-university relationships by fostering increased levels of trust and reciprocity (Green et al., 2020; Ingvarson et al., 2014; Le Cornu, 2012). It is also apparent that there is a need for partnerships to acknowledge and address any perceived issues of imbalance that may exist. An example of this may include the notion that for university providers, professional experience placements are a mandatory part of operations whilst for schools, the choice to engage in the process is voluntary. This potentially leads to a perceived power imbalance, exacerbated by such factors as shortages of placement opportunities (Top of the Class report, 2007). Whilst for schools, there also exists a valid concern that having a student teacher may disrupt normal operations and class dynamics due to the requirements for supervising a PST whilst on placement (Rowley et al., 2013).

The role of leadership has also been identified as a key factor contributing to partnership efficacy. Often this starts at the top with the school principal and then cascades down through all levels of staffing at the school. The adoption of a distributed leadership model provides a positive framework to support partnership sustainability and helps to bridge any perceived cultural or practical divide that may exist (Allen & Peach, 2007; Le Cornu, 2012; Greany, 2015). The ability to broker a shared vision and understanding between stakeholder groups is another significant factor, particularly relevant with regard to what constitutes a partnership in relation to teacher education with particular emphasis on the clarity around roles and role statements (Loughland & Ryan, 2020). For this reason, the scope and definition of the roles in addition to titles selected to represent those roles are considered important for partnership sustainability and succession planning (Greany, 2015; Trent & Lim, 2010). Further, Loughland and Ngyuen (2020) proffer that the ability of stakeholders to reach a shared vision is paramount if a partnership is to be successful, drawing from collective efficacy to engage in authentic partnership planning and identification of shared feasible objectives. Greany (2015) identifies that adoption of a staged approach in establishing and maintaining partnership activity, supported by a clear communication strategy, linked to identified shared objectives, and an inclusive culture in regard to decision-making and evaluation (Rowley et al., 2013) are vital to mitigate any plateauing of activity.

3.5 Refocusing the School-University Partnership

In recent times, there has been a genuine attempt to align university practice with specific industry and workforce needs. In NSW, this has been supported through a state-wide initiative aimed at producing both innovative and sustained quality learning opportunities and professional practices aligned with the transitional activity of teacher education professional experience (Winslade et al., 2021). The HUB school program, initiated by the NSW DoE, sought to bring together a range of schools and universities supported by a school-focused research paradigm. The aim was to establish a knowledge bank of evidence-based practices to support the needs of not only pre-service teachers but also their placement schools and universities (Bruniges et al., 2013). As such, the program has provided the opportunity for both school and university stakeholders to connect, or in many cases reconnect, in a meaningful and respectful way to spend time exploring each culture and gaining a better understanding of the needs, priorities, and perspectives that represent their individual approaches to teacher education. This space has been referred to by some including Ziechner (2010) as the third space, a space where expertise from differing ITE preparation perspectives overlaps in efforts to provide the best teacher education practices possible.

3.6 Details of the NSW Partnership—The HUB Schools Program

Historically, concerns have been raised by school-based practitioners around ITE in Australia and the perceived lack of authentic links to the needs of students transitioning to the classroom. This concern was reflected in the 2014 Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) review, highlighting the need to address the classroom readiness of graduate teachers. The review emphasised the need for greater collaboration between universities as higher education providers and school systems, with the aim to improve student outcomes inclusive of professional experience as a critical element (Craven et al., 2014).

In NSW, the accrediting body, the NSW Standards Authority (NESA) mandates that every pre-service teacher completes between sixty and eighty days of professional experience in schools (NESA, 2017). Following the release of the TEMAG evaluation and the NSW Great Teaching Inspired Learning [GTIL] blueprint for action, the NSW DoE HUB initiative was introduced as a means of providing a platform to allow school and universities to re-engage in partnership conversations. This blueprint provided the opportunity for recognition of concerns that both sets of stakeholders had become distanced with regard to their contribution to teacher education impacting on the perceived level of graduate quality and classroom readiness (Clarke & Winslade, 2019). The initiative identified twenty-four NSW DoE schools recognised for their commitment to supporting PEx programs with the capacity to engage with university providers in order to explore options and pathways to work together to increase the perceived quality of the overall PEx for PSTs. Each of the identified schools was partnered with a university, based on appropriate location and ITE course profiles (NSW DoE, 2021). The initiative was underpinned by a strengths-based philosophy. The view was to shift away from a model of adding practice to an established theoretical foundation to a more inclusive model with both sets of stakeholders (university and school) more actively engaged in developing innovative delivery methods. In this way, the stakeholders were supporting a smoother transition from PST to a classroom ready graduate.

The DoE articulates that objective of the HUB schools program being introduced was to target initiatives supporting the professional development of both pre-service teachers and supervising teachers (Centre for Educational Statistics and Evaluation [CESE], 2018, p. 7). For PSTs, this was inclusive of innovative and revised induction and supervision models, increased levels of professional development availability and the provision of additional support mechanisms. For supervising teachers, the focus was increased levels of recognised professional learning in addition to increased access to support structures in the partnership. One focus of the study underpinning this chapter was the inclusion of funding and support to revise and develop the ITE preparation course content and deliver it in a way that benefited all stakeholders and promoted collegiality (CESE, 2018). Recommendations outlined in the GTIL (2013) blueprint for action identified that, “Specialist professional experience schools will showcase high quality professional placement practice” (Bruniges et al., 2013, p. 10). In response, the NSW DoE established the opportunity for schools to engage in a partnership building activity. This partnership was initially tested on a three-year pilot cycle, with an opportunity to extend, where partnerships were sustainable and focused on strengthening the relationships between schools and ITE providers. Key focus areas in the first three years of the initiative included the establishment of a mentoring website to provide state-wide support for partnership teams and study of assessment in professional experience. The second three-year iteration of the HUB school program was characterised by a shift towards a more empirical approach to collecting data as evidence. This second iteration focused on the sharing of practice and learnings from the first iteration. The developing role of the Professional Experience Coordinator (PEXC) was identified as a key element from these meaningful partnerships.

One of the key elements of university involvement was the opportunity to work closely with the NSW DoE to provide an evidence-based approach to address issues raised in the TEMAG (2014) report. One of these issues was the need to clarify the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders including ITE providers, education departments, schools, and authorities in an effort to prioritise needs, tasks, and accountabilities (Craven et al., 2014). For ITE providers, the partnership also provided the opportunity not only to leverage relationships with schools to make more meaningful connections, but to increase the quality of PEx for PSTs, and also collect significant data to be utilised as research-based evidence to share with the wider ITE community (McIntyre, 2017). A key focus area that emerged from this process and underpinned the research paradigm was the role and responsibility of the school-based PEXC as central to the success of the school-university partnership.

3.7 The Role of the Professional Experience Coordinator (PEXC)

The NSW PEx HUB study has shown that role of the PEXC is central to perceived efficacy of the HUB schools project if it is to be considered a community of practice (CoP) (Wenger, 1998). Jones et al. (2016) highlights that the role of the PEXC has been both under-researched and underestimated and refers to PEXCs as the unsung heroes of PEx. PEXC is a role that is often surrounded by a lack of clarity around the complex and layered nature of the role. In order to provide meaning to the study, it was important to unpack the position of the PEXC as a legitimate boundary crosser with the ability to navigate between two differing cultural settings providing connection and commonality to all stakeholders (Akkerman & Bruining, 2016; Greany, 2015; Mutton & Butcher, 2007). Literature suggests that the positioning of the PEXC in the school hierarchy is important. For example, if the PEXC role is aligned to the principal or deputy principal, the PEXC may be perceived in an administrative capacity and removed from the PST supervisory process. Therefore, the PEXC position needs to be more closely aligned to the PEx and the quality learning outcomes (Martinez & Coombs, 2001). Whilst the PEx Framework (NESA, 2015) provides a level of clarity around the PEXC role, anecdotal evidence would suggest that this has not been enacted through policy implementation. The significance of the PEXC role becomes clear when examining the TEMAG review with its focus on the need for ITE graduates to be classroom ready and to have the ability to take up a teaching role directly following graduation. One of the key elements that support this outcome is the assurance of quality PEx that are aligned with the Professional Standards for Teachers (AITSL, 2017). Key issues identified in PEx include a perceived variance in the quality associated with PEx as experienced by PST, the perceived low value and profile of PEx in schools, mentors, and coordinators (Craven et al., 2014). These issues along with the impact of the PEXC will be unpacked in the findings of this chapter.

3.8 Methodology

This section of the chapter draws on a collective research project that underpinned the second iteration of the NSW HUB school initiative (2019–2021) focusing on the role and responsibility of the school-based PEXC.

The study was qualitative in nature and adopted a quasi-narrative approach to collecting data. Data were collected from (n = 24) school-based Professional Experience Coordinators (n = 20), and Principals (n = 20) from participating HUB schools in addition to partner university-based Professional Experience Coordinators (n = 12). Data were collected via semi-structured interviews. The research method was considered appropriate in order to provide an understanding and reflection on the specific experiences of the three identified stakeholder groups within the specific context of the NSW HUB school program.

The study was informed by the following research questions:

-

1.

What is the role of the Professional Experience Coordinator (PEXC) in enhancing professional experience in teacher education?

-

2.

What strategies do PEXCs, Principals and University Coordinators in partner universities see as supporting the development and quality of the PEx HUB school program?

3.9 Data Analysis

As data were collected from three sources (school-based PEXCs, school principals and university PEXCs), triangulation of evidence was feasible in addressing the identified research questions. The research project, led by the University of New South Wales, was granted ethics (HC190505) and approval to conduct research in schools through the NSW Department of Education (SERAP2019413). Data were analysed thematically through the lens of key constructs aligned with identified literature. The research analysis was conducted by the three lead investigators (comprised of the chief investigator and 2 independent research assistants) from the lead university on behalf of the larger collective. They adopted a cyclical approach supported through regular research meetings allowing for discussion of emergent themes. This process provided a level of mitigation through verification and corroboration to ensure that researcher bias would not be a factor. An independent research assistant provided a mitigating mechanism against the risk of data reductionism aligned with coding through the use of NVivo and in conjunction with the research team. The research team then returned to the interview transcripts to verify claims made in the report. The draft report was then circulated to participants, in order to affirm accuracy and representation of the data.

3.10 Discussion of Summarised Findings from the Study

The following section of the chapter will provide a summarised overview of the findings of the study that have been consolidated into a report to be presented to both the NSW DoE and the NSW Deans of Education.

The study found that there was strong evidence that the PEXC played a significant role in determining the efficacy of school-university partnerships, particularly in the development and sustainability of a professional learning culture. It was also shown that the role of the PEXC enhanced the status of professional experience in schools, with direct alignment to an increased number of teachers willing to supervise PSTs in addition to an improvement in the standard of that supervision. This reduced the level of historical variance with regard to quality of supervision. The study also identified a range of potential strategies that could be adopted including improved clarity with regard to roles and responsibilities, accountability, communication, and documentation processes. In addition, factors such as placing a greater emphasis on the coordinator role in terms of program planning, development, and delivery of ITE courses in both school and university contexts were identified.

There were a number of challenges highlighted with regard to the role of the PEXC including sustainability of the role. A key factor of sustainability was the time allocated to the role and the need to ensure sufficient workload capacity to undertake the responsibilities required to successfully support a PEx program. A successful element of the second iteration of the HUB program was the dedicated funding for time release of PEXCs in each HUB school. This financial commitment resulted in recommendations that an appropriate funding model to support the release of time required for a PEXC was necessary. Findings suggested that by incorporating the PEXC role in the executive structure of schools would provide an opportunity for a broader role that would ensure a higher degree of quality assurance for PSTs and provide professional learning and development for stakeholders. Ultimately, the study found that there was a strong consensus with regard to the positive impact of the PEXC on PEx programs across the network of HUB schools. The PEXC was identified as key to raising the profile, value, and status of PEx as a core activity of the school by improving both the quality and consistency of supervision and assessment protocol. Further, it was shown that that PEXCs were considered critical in shaping the culture of PEx within the school and fostering a more positive seamless transition from university study into the teaching environment. Overwhelmingly, the consensus was that the PEXC had significant influence on the outcomes of PEx experiences.

This study also found that the professional, personal, and social domains and the overall position of professional experience within the wider teacher education framework were highly influenced by the PEXC. These key areas included modelling professionalism, establishing collaborative collegialism, understanding school activities and multiple stakeholders in a holistic sense, and increasing PST’s confidence, efficacy, and sense of belonging inside and outside the classroom. It was noted that a PEXC role was valuable in terms of ensuring that PEx was prioritised in the school ensuring a quality experience for the student teacher. Further, and of significance to universities, one of the most significant impacts of the PEXC was seen in relation to the way in which PSTs “at risk” were managed and resolved. It was identified through the study that the importance of relationships built on trust and understanding of how a CoP operates. This was exemplified through the example of a particular PEXC managing and resolving a situation where a PST required additional support in order to successfully complete their placement. The study identified that PEXCs help students get over the line and are needed to build relationships and connect with appropriate people needed to develop support plans and mechanisms. This included the development of process and support structures and the ability to take a framework and align it with the needs of the particular school, university, and student specific to that situation.

Funding and time were identified as key issues impacting sustainability across all three stakeholder groups with clear identification of appropriate workload (time) allocation to PEXC activities. This is inclusive of the time required not only to design and deliver effective programs, but to also adopt a proactive approach to the process in order to integrate innovative practice, and increased and active reflection. It was shown that the increased emphasis on funding and alignment to expected outcome deliverables of the HUB program, such as development of professional development material, clearer placement protocols, and induction procedures elevated the value and perceived status of the PEx programs. Further, it was identified that there needed to be a degree of flexibility associated with the allocation of time in recognition of the complex nature of the role and the range of variables that need to be taken into account. Timetabling issues such as the impacts on the individual school depending on the time of the term and where the term sits were further impacted by the timings of the university year and ability to integrate into the school calendar. The complex nature of the PEXC role was likened to a project manager pulling together the strings that underpin the complex web of relationships contributing to PEx. The PEXC role was seen to involve a number of key phases including an establishment phase with a focus on the establishment of relationship building with key stakeholders in order to produce a range of processes and procedures and supporting structures to facilitate placements. Following the establishment phase is a period of consolidation focusing on improvement and growth leading into the opportunity for reflection.

The role of the PEXC was found to be critical to ensure that the facilitation of the PEx process was efficiently managed, inclusive of clear channels of communication. This was particularly recognised from the stakeholders representing university programs as vital to a smooth and efficient transition of the PST into their placement. For universities working with both dedicated PEXC and schools that operated without a coordinator, there were noted operational differences with regard to time, space, and attitudinal approach. A flexible approach to workload and use of funding was identified as a key enabler supporting schools to build quality PEx. This included the ability to allocate time to the professional development of supervising teachers, increased emphasis on planning and liaison with stakeholders such as the PST prior to placement, and university PEXCs supporting a more cohesive CoP. Further, the flexible use of time allocation also allowed the PEXC to attend a range of workshops and conferences building their own skillset and profession network outside of the school environment. The notion of time as an allocated resource was viewed as critical if there is to be increased levels of buy in from school-based staff to take on the role as supervisors of PST in order to engage in professional dialogue and training and develop a consistent and quality approach to supervisory practices. In doing so, this supports moving away from an individual educators obligatory sense of having to give back to the profession and viewing supervision as another task to be undertaken on top of an already perceived busy schedule, towards an active role in a well-designed quality and integrated component of a PST’s professional journey.

3.11 Conclusion

The study described throughout this chapter was underpinned by a collective approach between NSW ITE providers to gather evidence to support the push for increased recognition of the significant role that school-based PEXCs play in raising the status of PEx in ITE. The initiation of the HUB school program by the NSW DoE has provided a new opportunity for NSW university PEx providers to collaborate as a legitimate community of practice aligning professional practice with a research-focused paradigm. As such, this is new ground for many working in the PEx space and has helped to build collegiality across the field with a range of new working groups and research projects being negotiated; whilst this was not an original key outcome of the study, it has been a welcome addition. Significantly, the study has shown that the role of the PEXC is an under-researched and underestimated position that if provided with the appropriate recognition, value, and resources, has the ability as legitimate boundary crosser to raise the status, profile, and quality of PEx programs, benefiting all stakeholders.

3.12 Recommendations

A tangible outcome from the collective NSW study was a series of recommendations; these included increased recognition and remuneration of the PEXC role aligned with an executive appointment inclusive of quality assurance of PEx programs and student teachers. Secondly, that PEXCs are given increased opportunities to work more closely with university ITE providers, codesigning, delivering and reviewing teacher education programs and actively lecturing and tutoring in the university setting. The study also recommended that the collective of universities involved in the HUB school program and the school partners work together in future iterations of the program to codesign and develop a standardised approach to PEx documentation. This includes the PEx handbooks consisting of common core elements that exist across all ITE courses in NSW. Finally, it is suggested that regular meetings that have been established to bring together the state-wide HUB school PEXCs which has become a legitimate CoP continue into the future to develop consistent practices across NSW aligned to relevant DoE priorities and strategies.

3.13 Limitations

The authors acknowledge that this particular study was aimed at gathering the perceptions of a group of stakeholders aligned to the HUB initiative, and as such, the sample might not be reflective of the wider school community across the state or from other schooling systems. The study also did not collect data from PSTs with regard to their perceived efficacy of the school-university partnerships. Whilst individual partnerships have explored the perceptions of PSTs, they are not represented in the findings here. The decision to support and fund future iterations of the HUB program will provide the opportunity to bring other stakeholders such as student teachers into the research paradigm. Additionally, it must also be noted that the PEXC results provided in this study were identified as the result of a funded release for PEXC, and as such, generalisability of results would be dependent on availability of similar funding models or support for appropriate workload release.

3.14 Impact of COVID-19 on the Project

The timing of the pandemic had a noticeable impact on both the community of practice that forms the school-university partnerships that underpin this chapter and the timeframes required for partnerships to achieve intended outcomes. During 2020 and 2021, the NSW school system experienced an unprecedented level of disruption to day-to-day operations with a significant shift to online learning leading to reduced PEx opportunities. This was accompanied by various restrictions and ability for schools to provide access to non-essential personnel. The study informing this chapter occurred during a unique socio-political context fuelled by high levels of uncertainty, characterised by backlogs of placements, and university organisational restructures resulting in loss of corporate knowledge. This increased the pressure on school and university relationships.

3.15 Where to Next?

The submission of a report to the DoE on behalf of the PEx collective and supported by the NSW Council of Deans of Education coincided with the end of the second three-year iteration of the HUB school program. The report consolidated the learnings achieved during this time and supplemented a series of individual acquittal reports from each of the school-university partnership groups. After considering individual reports and evaluating the impact of the partnerships across the state, the Department and Deans of Education have agreed to enter a third round of partnerships and are currently in discussions to determine the direction and outcomes that will underpin a new wave of school-university relationships. Early discussions have identified that the future focus will look to develop partnership strategies to address potential workforce shortages in particular regions and disciplines across the state, whilst also maintaining a clear focus on the continued development of practices that support quality PEx and transition from university to the teaching environment.

References

Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers (2014). Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG). Retrieved at: https://www.studentsfirst.gov.au/teacher-educationministerialadvisory-group

Akkerman, S., & Bakker, A. (2011). Boundary crossing and boundary objects. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 132–169.

Akkerman, S., & Bruining, T. (2016). Multilevel boundary crossing in a professional development school partnership, Journal of the Learning Sciences, 25(2), 240–284.

Allen, J. M., & Peach, D. (2007). Exploring connections between the in-field and on-campus components of a preservice teacher education program: A student perspective. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 8, 23–36.

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (AITSL). (2017). Australian professional standards for teachers. Retrieved at https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards

Australia. Parliament. House of Representatives. Standing Committee on Education and Vocational Training. (2007). Top of the class: Report on the inquiry into teacher education. Retrieved from hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/1009

Bruniges, M., Lee, P., & Alegounrias, T. (2013). Great teaching, inspired learning. A blueprint for action. Retrieved: schools.nsw.edu.au/media/downloads/news/greatteaching/gtil_blueprint.pdf

Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation. (2018). Great teaching, inspired learning professional experience evaluation report. NSW Department of Education, cese.nsw.gov.au

Clarke, D., & Winslade, M. (2019). A school-university teacher education partnership: Reconceptualising reciprocity of learning. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 10(1), 138–156.

Craven, G., Beswick, K., Fleming, J., Fletcher, T., Green, M., Jensen, B., … Rickards, F. (2014). Action now: Classroom ready teachers. Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). Teacher education and the American future. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 35–47.

Greany, T. (2015). How can evidence inform teaching and decision making across 21,000 autonomous schools? Learning from the journey in England. In C. Brown (Ed.), Leading the use of research & evidence in schools. IOE Press.

Green, C., Tindall-Ford, S., & Eady, M. (2020). School-university partnerships in Australia: A systematic literature review. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 48(4), 403–435.

Grima-Farrell, C., Loughland, T., & Nguyen, H. (2019). Theory to practice in teacher education the critical challenge of translation. Springer Singapore Pte. Limited.

Ingvarson, L., Reid, K., Buckley, S., Kleinhenz, E., Masters, G. & Rowley, G. (2014, September). Best practice teacher education programs and Australia’s own programs. Department of Education.

Jones, M., Hobbs, L., Kenny, J., Campbell, C., Chittleborough, G., Gilbert, A., & Redman, C. (2016). Successful university-school partnerships: An interpretive framework to inform partnership practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 108–120.

Le Cornu, R. (2012). School co-ordinators: Leaders of learning in professional experience. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(3), 18–33.

Le Cornu, R. (2016). Professional experience: Learning from the past to build the future. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 44(1), 80–101.

Loughland, T., & Nguyen, H. (2020). Using teacher collective efficacy as a conceptual framework for teacher professional learning—A case study. Australian Journal of Education, 64, 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944120908968

Loughland, T., & Ryan, M. (2020). Beyond the measures: The antecedents of teacher collective efficacy in professional learning. Professional Development in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2020.1711801

Lynch, D., & Smith, R. (2012). Teacher education partnerships: An Australian perspective. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(11), 132–146.

Martin, S. D., Snow, J. L., & Franklin Torrez, G. A. (2011). Navigating the terrain of third space: Tensions with/in relationships in school-university partnerships. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(3), 346–311.

Martinez, K., & Coombs, G. (2001). Unsung heroes: Exploring the roles of school-based professional experience coordinators in Australian preservice teacher education. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 29(3), 275–288.

McIntyre, D. J. (2017). The power of clinical preparation in teacher education. In R. Flessner & D. R. Lecklider (Eds.), The power of clinical preparation in teacher education (pp. 197–210). Rowman & Littlefield.

Moran, A., Abbott, L., & Clarke, L. (2009). Reconceptualising partnerships across the teacher education continuum. Teachers and Teacher Education, 25, 951–958.

Moss, J. (2008). Leading professional learning in an Australian secondary school through school-university partnerships. Asia Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 36, 345–357.

Mutton, T., & Butcher, J. (2007). More than managing? The role of the initial teacher training coordinator in schools in England. Teacher Development, 11(3), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530701644565

NESA. (2015). A framework for high-quality professional experience in NSW schools. Retrieved from https://www.educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/portal/nesa/teacher-accreditation/how-accreditation-works/administeringaccreditation/supervisors-principal-service-providers/professionalexperienceframework

NESA. (2017). Professional experience in initial teacher education. NSW Education Standards Authority. https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/wcm/connect/6807e5d6-b810-4e57-bc32-1a3155fd115e/professional-experience-in-ite-policy.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=#:~:text=A%20professional%20experience%20internship%20is,supervision%20by%20the%20classroom%20teacher.

NSW Department of Education. (2021). Professional experience Hub Schools. Retrieved from https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/professional-learning/pl-resources/pre-service-teacher-resources/professional-experience-hub-schools

Rowley, G., Weldon, P., Kleinhenz, E., & Ingvarson, L. (2013). School-university partnerships in initial teacher preparation: An evaluation of the school centres for teaching excellence initiative in Victoria. Australian Council for Educational Research.

Smith, K. (2016). Partnerships in teacher education—Going beyond the rhetoric, with reference to the Norwegian context. Centre for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 6(3), 17–36.

Trent, J., & Lim, J. (2010). Teacher identity construction in school-university partnerships: Discourse and practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 1609–1618.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

Winslade, M., Daniel, G., & Auhl, G. (2021). Preparing for practice: Building positive university-school partnerships. International Journal of Teaching and Case Studies, 11(4), 302–316.

Zeichner, K. (2010). Rethinking the connections between campus courses and field experiences in college and university- based education. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 89–99.

Zeichner, K. (2018). The struggle for the soul of teacher education. Routledge.

Zeichner, K. (2021). Critical unresolved and understudied issues in clinical teacher education. Peabody Journal of Education, 96(1), 1–7.

Acknowledgements

Dr Jennifer Barr: University of New South Wales

Associate Professor Iain Hay: Macquarie University

Associate Professor Fay Hadley: Macquarie University

Jacqueline Humphries: Western Sydney University

Nicole Hart: University of Sydney

Associate Professor Wayne Cotton: University of Sydney

Professor Boris Handal: Notre Dame University

Sarah James: Southern Cross University

Dr Robert Whannel: University of New England

Chrissy Monteleone: Australian Catholic University

Dr Deb Donnelly: University of Newcastle

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Winslade, M., Loughland, T., Eady, M. (2022). Reimagining the School-University Partnership and the Role of the School-Based Professional Experience Coordinator: A New South Wales Case Study. In: Bradbury, O.J., Acquaro, D. (eds) School-University Partnerships—Innovation in Initial Teacher Education. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5057-5_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5057-5_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-5056-8

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-5057-5

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)