Abstract

Partnerships in teacher education are a priority for governments, universities and schools with widespread belief in the importance of working together. There are many potential benefits to working collaboratively and this chapter explores the reasons for involvement and perceived benefits for participants in this school-university partnership in Melbourne, Victoria. Interview data from participants reveal their desire to be involved in a partnership to develop ongoing and long-term relationships. Participants highlighted the importance of pre-service teachers (PSTs) gaining knowledge and understanding of the community in which the school was situated. PSTs identified their involvement in the designated tutorial group as central to their positive experiences as first-year undergraduate students in a Bachelor of Teaching/Bachelor of Arts as it gave them a sense of belonging. Participants from all participant groups indicate a desire to deepen the partnership and strengthen the ties for mutual benefit.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

50.1 Introduction: The Value of Partnerships

The role of schools, school systems and universities in the preparation of teachers and the importance of collaboration between these stakeholders has been highlighted (Kruger et al. 2009). In both England and the United States of America (USA) there has been a push towards school-university partnerships since at least the 1990s, exemplified in the Professional Development School movement in the USA (Burn et al. 2017; Darling-Hammond 1994; Cozza 2010; Darling-Hammond and Bransford 2005; Darling-Hammond 2006). In Australia school-university partnerships have been identified as an important element of effective teacher education programs (Green et al. 2020; Jones et al. 2016; Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group 2014). School-university partnerships have been emphasised in successive reviews into teacher education including the report from the Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group (TEMAG) where formal partnerships were encouraged (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Education and Vocational Training 2007; Kruger et al. 2009). Despite this widespread belief in partnerships, insecurity of funding to support them been a significant challenge to the sustainability of Australian and in instances international school-university partnerships (Allard et al. 2012; House of Representatives Standing Committee on Education and Vocational Training 2007; Kruger et al. 2009; O’Doherty and Harford 2017; White et al. 2018). Apparently, for funding authorities the benefits of partnerships are not sufficient to warrant on-going support and yet there is a widespread assumption that partnerships are valuable. At least among university teacher educators there has been persistent efforts to create partnerships whatever their challenges (for example, Allard et al. 2012; Darling-Hammond 2006; Jones et al. 2016; Kruger et al. 2009).

This chapter seeks to make explicit the significance of partnerships for participants. In analysing partnerships, it is important to note that school-university teacher education partnerships can vary from formalised agreements covering a range of shared activities such as working with pre-service teachers (PSTs) and shared research, to much looser arrangements which involve little face to face contact but consist in agreeing to share responsibilities of the education of PSTs (Kruger et al. 2009; Ryan and Jones 2014). In this chapter we are considering the value of a partnership which is at the more elaborated end of the scale, thereby focusing on the perceived benefits of a partnership which involves both school and university participants engaging in a range of relationship-building activities.

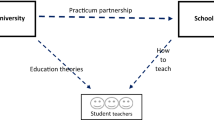

The professional literature on partnerships has stressed their capacity to create the connection between theory and practice that has been identified as a crucial element of effective teacher education (Allen and Wright 2014; Green et al. 2020; Jones et al. 2016; Schuck 2013). Criticism of teacher education often points to a lack of continuity between the theory work completed at university and the practical element experienced on placement (Grudnoff et al. 2016; Jones et al. 2016). While there is criticism of this theory/practice binary as problematic (Ord and Nuttall 2016), it continues to be identified as a challenge for teacher education (Mayer et al. 2017). PSTs consistently rate their time in schools on placement as the most important part of their preparation to teach and tend to see it as disconnected from the academic components of their program (Ure 2009). Strong, collaborative partnerships between schools and universities, it is argued, enhance the experience of PSTs and help them to see the links between theory and practice (Jones et al. 2016; Walsh and Backe 2013).

Partnerships between schools and universities have the capacity to provide mutual benefits which lead to more effective teacher education (Jones et al. 2016; Kertesz and Downing 2016; Schuck 2013). Schools are able to provide feedback to universities about the skills and preparedness of PSTs which can inform the work of the university. Universities are able to provide access to current research and an evidence base for school practices (Walsh and Backe 2013). The shared goal of teacher graduates who are well prepared and effective is a strong incentive for collaboration. In the following section, the partnership explored in this research is outlined.

50.2 The Catholic Teacher Education Consortium (CTEC)

The Catholic Teacher Education Consortium (CTEC) was formed in the second half of 2012 as a response to an identified need for adequate staffing for Catholic secondary schools. A governance committee at Australian Catholic University (ACU) saw the importance of ensuring that there would be sufficient number of suitable teachers to meet the staffing needs of Catholic secondary schools in the north and west of Melbourne. This area has seen significant growth in enrolments, with the outer north and west in particular experiencing strong demand for school places and therefore a need to recruit additional staff (Catholic Education Melbourne 2014). Given this situation, the governance committee at the university, which includes a Principals’ representative, decided that a dedicated approach to meeting these staffing needs was required. CTEC was developed as a result and is a partnership between Australian Catholic University, Catholic Education Melbourne (CEM) and 16 Catholic Secondary schools (initially 14 schools and in 2018 the number dropped to 15). CTEC was developed as a specialised program within the Bachelor of Teaching/Bachelor of Arts (BT/BA) where PSTs who opt into the program have participated in a dedicated tutorial and completed their Community and Professional Experience within CTEC schools. The program was designed with a number of elements including: immersion of PSTs in the school communities; on-site tutorials for some classes; paid employment for third and fourth year PSTs; working with career staff in the schools to promote higher education to students; and a final element was to incorporate a research program alongside CTEC. The inclusion of a research project as part of the initial plan is unusual for this type of partnership project (White et al. 2018).

The range of elements as part of the partnership are connected to its broader aim, to meet the future staffing needs of these schools with teachers who are well prepared to teach in these particular contexts. While the CTEC schools vary, as many as half of the enrolled students in participating schools were in the bottom quartile in the Index for Community and Social Educational Advantage (ICSEA) and up to almost 90% of students from a language background other than English (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority 2017). Evidence from the large-scale, longitudinal “Studying the Effectiveness of Teacher Education” research project found that graduates who completed placements in culturally and linguistically diverse contexts were more confident about their preparedness and effectiveness in these contexts upon graduation (Mayer et al. 2017). Moreover, among the aspirations for the CTEC program was the idea that PSTs who had attended one of the CTEC schools might be attracted to join the program and then return to teach in the area. Further it was hoped too that PST presence in the schools might encourage school students to consider studying teaching at the university, thereby promoting stronger educational outcomes.

CTEC also aims to promote relationships within and between the university, the school sector and the Catholic secondary schools taking part in order to ensure the provision of a high quality BT/BA experience to the PSTs and to encourage them to take up employment at CTEC schools upon graduating.

The rationale for governments, universities and school systems to be involved in partnerships is relatively well defined and described above. These institutions all have a vested interest in the effective preparation of teachers so that schools are well equipped with the staff to provide for the educational needs of students. The research in this chapter reports on the motivators and benefits identified particularly by PSTs and staff in the CTEC schools. The reasons for being involved in the project are explored in order to better understand the perceptions of PSTs and staff in CTEC schools of the benefits and challenges to partnership participation. Their responses have the potential to illuminate what high quality teacher education means for participants. The findings indicate that for these principals, teachers and PSTs school-university partnerships offer the opportunity to build relationships not as part of brief placements but through more long-term connections with schools and their communities.

50.3 Theoretical Framework

The framework of third space theory has been used in this research in order to examine this school-university-system partnership (Bhabha 1994; Soja 1996). Third space theory identifies the potential for working outside of and across institutional boundaries (Bhabha 1994). Third space is about the creation of hybrid spaces where practitioner and academic knowledge are valued and the apparent boundaries between theory and practice are blurred. The aim is to reduce hierarchies between the project participants in the education of teachers. Anagnostopoulos et al. (2007) describe a third space approach as promoting recognition of “horizontal expertise” (p. 138) whereby the unique knowledge of professionals from different areas can contribute to professional practice. This concept of horizontal expertise builds upon the work of Engestrom and colleagues (Engestrom et al. 1995; Kerosuo and Engestrom 2003) in examining cross-institutional work, particularly in health-care organisations, in order to develop innovative solutions to improve patient care. In the case of teacher education this concept includes recognising the expertise of community members, education systems, schools and universities in developing graduate teachers with the skills and knowledge needed to function effectively in schools (Zeichner et al. 2015).

Third space theory has been applied in a range of domains with its origins in cultural theory (Bhabha 1994). Operating in this space provides the opportunity to “combine diverse knowledges with new insights and plans for action” (Muller 2009, p. 166). Third space creates opportunities for “challenging assumptions, learning reciprocally and creating new ideas” (Muller 2009, p. 166). The third space is generally conceived of as an abstracted, conceptual space but in its application to teacher education the idea can take a physical form in the shape of university classes delivered on school grounds with university teacher educators working alongside teacher practitioners. It can also be exemplified through teacher practitioners in schools developing and or delivering course materials for the university. These examples represent a literal crossing of institutional boundaries but a third space approach to teacher education is more than this and involves a reconceptualising and reimagining of the role of teacher educator (Norman-Meier and Drake 2010).

Forgasz et al. (2018) describe the application of third space theory in teacher education as a “new paradigm” that is “gaining momentum” and provides an opportunity for “reconceptualising partnerships in initial teacher education” (p. 34). A distinguishing feature of third space theorists identified by Forgasz et al. (2018) is that Soja’s (1996) is an intentionally created space whereas Bhabha’s (1994) is not a space we choose but rather “a way of understanding the in-between experience of cultural difference” (Forgasz et al. 2018, p. 36). From the perspective of this study, the third space we are exploring is both an intentional creation of the partnership as well as an inevitable in-between space that comes as a result of different institutions (schools, university, education sector) working together.

It is important to acknowledge the challenges for teacher educators working in the third space (Williams 2014). There are significant differences in goals and structures between universities, schools and school systems. Operating across these boundaries requires teacher educators to “…negotiate potentially difficult relationships between teachers, teacher educators and, at times, student teachers” (Williams 2014, p. 325). The experiences of teacher educators in school-university partnerships include “…building and negotiating complex relationships…” as “…central to the work” (Martin et al. 2011, p. 305). Not the least of the challenges is resolving practical and logistical challenges such as aligning university and school timetables and teaching terms.

Teacher education in the third space presents an opportunity to respond to criticism of theory-practice disconnect (Clemens et al. 2017; Forgasz et al. 2018). Even in school-university partnership models such as the Professional Development Schools in the United States there is still often a perceived distance between theory and practice. The intended long-term scope and multi-layered approach of the CTEC project including working with PSTs, a range of staff in the schools including principals, PST Coordinators and pathways staff, and education system staff, provides an opportunity to further integrate PST understanding of theory and practice, through “mixing, blending and hybridization” (Ryan et al. 2016, p. 179). These layers of the partnership have attempted to build in a range of teacher education program elements that are known to enhance PST experiences such as: being part of a specialized cohort; close connections between university staff and placement schools (Le Cornu and Ewing 2008; Rowley 2013) and learning about the students and communities they are teaching in (Ure 2009). It is intended that this enhanced experience will aid the development of well-prepared graduate teachers with the skills and knowledge needed in the schools in which they will teach.

50.4 Methodology

In order to investigate the value of these project elements from the points of view of participants researchers used a mixed methods approach with a combination of surveys and interview data collected. Surveys were completed by the PSTs upon entering the three-year program and then twice more during their program. The data collected through the surveys was focused around reasons for entering into the program as well as some demographic data such as the type of school they attended (single-sex, co-ed, Catholic or non-Catholic) and the area in which they attended school (north or west of Melbourne or other). Using a five-point Likert scale participants were asked to respond to a series of statements regarding their reasons for becoming involved in the program and their thoughts regarding teaching in Catholic schools. As the research has followed the first two cohorts, surveys were not completed in subsequent years; instead more investigation of PTS’ perceptions of the program was conducted through semi-structured individual and small group interviews. Similarly’s principals and teachers, staff from the University and staff from the school system were interviewed to explore the experience of being involved in the program and the partnership development. Interviews conducted included fifteen teachers, ten principals and four deputy principals, four staff from Catholic Education Melbourne and six staff from the university. A small number of the school participants have been involved in multiple interviews over the three years. A total of 39 PSTs completed surveys and two thirds of these PSTs also participated in the interviews. All interviews were recorded and transcribed.

This chapter explores the results of the interview data which were synthesised and analysed using Nvivo software. Thematic analysis informed by the work of Miles and Huberman (1994) was used with an inductive approach to coding the responses. The focus of this chapter mostly relates to comments made in response to the question, “what do you feel have been the benefits/highlights, if any, of being involved in the CTEC project?” which was asked of all participants. The PSTs were also asked “What were your reasons for becoming involved in CTEC?” and this was also a significant source for the comments on the emergent theme of building relationships. The prevalence of comments on this topic led to it being the subject of further exploration.

50.5 Findings

Inductive analysis identified “building relationships” as a theme from the interviews. Participants from each of the groups including PSTs, school staff, university staff and school-system staff identified the possibilities for building relationships as a significant aspect of the project. Within discussions around the benefits of building relationships and connection three sub- themes were identified: understanding the school community; a desire to deepen the partnership; and the benefits of the cohort experience.

50.5.1 Understanding the School Community

Participants in the research were asked to identify their initial motivations for becoming involved in the project and any benefits or perceived future benefits to involvement. More than half of the principals, deputy principals and teachers spoke about the long-term nature of the project as a benefit. One of the principals said that as a school they were:

looking at something that’s relatively ongoing and for people to have a sense of connection with the school and the culture and the environment at the school is probably very important so that’s probably one thing that struck us a little bit.

The comment above from a principal seems to be identifying the intended ongoing nature of the program as leading to PSTs having a better understanding of the school and a sense of connection to the community. This stands in contrast to the relatively common practice of short placements of a few weeks in the one school. Gutierrez and Nailer (2020) highlighted the importance of connection to community as a positive outcome of an extended professional experience placement as part of a school-university partnerships.

Below a principal discusses the consequences of the long-term and ongoing connections as part of CTEC as related to the importance of PSTs getting to know the schools:

I think the more school visits that those students can do the more they’ll get to know the schools where hopefully they will be applying.

and

If we can get young people from this region to come back to the region and teach with an understanding of the socioeconomic demands, the community demands, what it’s like to grow up in this community, then that’s really important for a teacher to have because I understand the social context from where the young people, our students, are coming. And that empowers a teacher to be able to understand the young people they’re teaching and the context from which they walk into the classroom.

The impression from the comments from principals above is that this project was worth investing in because it was about building up relationships and connection over an extended period of time. This was both in the sense that individual PSTs would have more than just one short teaching placement within the school community and also that the relationship with ACU through the project would be long-term. The principals and teachers in the schools identified the importance of PSTs getting to know the schools and community over time as central to their development as teachers who would be effective in these contexts. This aligns with the Studying the Effectiveness of Teacher Education findings around teaching in culturally and linguistically diverse contexts whereby similar professional experience placements were the key to feeling prepared (Mayer et al. 2017). As noted, one of the goals of CTEC is to recruit pre-service teachers who live in the same geographic area, which increases the likelihood of a culturally diverse teaching population, a strategy employed with some success in the U.S. (Sleeter 2001).

A teacher in one of the schools who had also herself been a student at another CTEC school further discussed the importance of teachers understanding the culture and environment of the school as critical to their effectiveness in connecting with students:

there is a self-awareness amongst the student body of this person’s like me so therefore I can share in their experience, or they can be a role model for me. Whereas if someone comes in who has had a totally different experience and is totally different … our kids are soccer kids, you will get not very many soccer kids at [another CTEC school]. So if you have someone that comes in here and is talking all about how they want to go out and play cricket and things like this, our kids are kind of going to go, mm, you’re not really like us, we might not identify with you as strongly. Whereas if you’ve got someone that comes in who’s really passionate and interested in things that they are interested in and can really build up that relationship and understand them, it’ll be more successful.

This teacher appears to be identifying the long-term connection with the schools as contributing to an understanding of community that would allow the PSTs to be successful in this school context. This call to understanding community is identified by Zeichner et al. (2015) as imperative for breaking down knowledge hierarchies and the creation of a third space in teacher education. The importance of a sense of community has also been highlighted in a recent systematic literature review of Australian school-university partnerships (Green et al. 2020).

It has been argued that effective school-university partnerships involve the university, and preferably the same staff, working with the same schools over a number of years (Le Cornu and Ewing 2008). This allows for the establishment of relationships between University and school staff in order to work together in the preparation of PSTs. It also allows University staff the opportunity to develop relationships with PST coordinators and mentor teachers over a period of time (Le Cornu and Ewing 2008). The support from participants for establishing these relationships over time suggests they may have had less than positive past experiences with short term projects or perhaps simply that they are more willing to invest in a project with long term aims. It is likely that some staff in schools will have had past experiences where resources to support partnership activity have not been sustained (White et al. 2018). From the point of view of the principals, the long-term possibilities are obvious in that they may have a pool of suitable graduates, known to the school, from whom to employ. For staff involved in the organisation of professional experience placements, established relationships with university staff and PSTs who are spending extended time working with the schools also offers clear benefits in a competitive placement context (Gutierrez 2016).

50.5.2 Deepening the Partnership

As part of the interviews with principals and teachers they were asked to describe their experiences of the partnership so far and also to suggest any possible improvements for the project. Responses to these questions varied with a number reflecting on the size and scope of the partnership and project overall. Given the competing demands and heavy workloads for principals and teachers, it was a sign of the belief in the value of the partnership that a number of principals and deputy principals suggested that they wanted to deepen and extend it. One principal below talks about how the relationship established through CTEC could be a springboard to other school-university collaborations:

I suppose you know I’d like to probably explore the aspect of greater collaboration with [university] in … in a whole range of different ways. You know one of our focuses for the next four years is around literacy and developing capacity in our staff to teach literacy explicitly right across the curriculum and so you know I’d be really interested in looking with [university] and to look at some of the things that they can offer in that regard and even just an evaluation along the way you know in terms of whether that’s something that is of use to a postgraduate student – Principal.

This principal has identified how the school and the university could work together in partnership in developing in-service teachers within the school and has recognised the possibility to utilise the resources and expertise at the university. This principal is identifying the almost limitless potential to build on the partnership in order to share resources and help meet each other’s goals. Brady’s (2002) study with primary school principals in NSW found that there was broad support for a range of partnership activity, including research. The principal quoted above recognises that university staff and postgraduate students need access to schools for research purposes and that the school and university could work together to meet the aims of both. While often research projects are developed by university staff who then seek schools to conduct these studies in, this principal is seeing possibilities for matching their needs with the skills and interests of those at the university.

On-site tutorials were conducted over a three year period and held at three different CTEC schools. One of these principals spoke of the desire of the school to be more involved with the PSTs when they were on-site:

In fact probably the only thing I’d say is it would [be] good if maybe while… the group’s here if we were involved a little bit more – Principal.

In discussing how the school could be involved the principal talked about teaching staff sharing their expertise as current classroom teachers in a CTEC school with the tutorial group:

I think it would be good for us to have some teachers go in and give some different opinions or give some experiences. Principal 2014.

This principal is identifying the possible benefits to staff at the school in having their experience and knowledge valued through an opportunity to share it with pre-service teachers. This recognition of the value of the different sets of skills and knowledge of the various participants in the partnership is emblematic of a third space approach (Anagnostopoulos et al. 2007).

For one teacher in the role of Pre-Service Teacher Coordinator, there was a need to meet with the other schools involved in the project in order to create a sense of partnership that she felt wasn’t there at the moment:

I really would like, you know, the 14 schools or the people in charge to just come together even once during the whole year and saying how are you travelling with your guys? What are you finding? How do you support yours? What are you doing that we might be able to do? I certainly don’t feel part of a group – Teacher.

Given the competing demands on schools, it is a sign of commitment to the aims of this project that this teacher is saying they want to invest more in it through dedicated face-to-face contact.

A number of principals also felt that an opportunity to get together in person would be beneficial to build a sense of the partnership. One principal said:

I guess I’d like to maybe get a forum with our principals to have a, let’s just share … and to get a bit of cross-fertilisation happening with our own thinking at principal level, I’d feel more confident hearing and sharing with them, now what do we think the benefits will be, what are we exploring here, what are our outcomes? – Principal.

There were opportunities for principals and staff from the university and Catholic Education Melbourne to get together at a yearly dinner but this may not have provided the opportunity for the sort of discussion this principal was seeking. The possibility of expanding the partnership to include more schools was raised by a number of participants. These comments were characterised by a sense that the possibility was there to expand the project:

There’s 14 in, the question could be well why aren’t there more? – Principal.

An additional two schools were recruited into the project in 2014. These two schools had been approached in 2012 as part of the establishment of the partnership but had not been in a position to commit at this time. In 2018 one of the original schools withdrew from CTEC, not from partnerships with the University, but to create one with a year-long internship model, suggesting, as this research does, that long term engagement in school communities is a goal for schools. A participant who worked at CEM indicated a desire to see the program extended to other geographical regions also:

I’d be looking to the possibility of maybe that sort of project operating in[X] region because I just think there are so many wonderful benefits. – CEM staff member.

These comments from participants suggest that they support the model that CTEC is using and can see room for its expansion.

Overall the benefits of the partnership were recognised by members of all participant groups, in particular the opportunities for building ongoing relationships and an understanding of the school communities with opportunities for continuing and expanding benefits for all partners. Participants seemed to recognise the opportunities for benefits to themselves and to other partners of being involved and it was anticipated that the project would grow and develop over time.

Demonstrating that the third space can be a place of creative relationships, a number of additional partnership activities have happened over the duration of the partnership thus far, including: leadership staff from one of the schools presenting to PSTs at the university; staff in schools developing resources to be used in university classes; CTEC schools participating in other research projects with ACU staff; three staff from CTEC schools teaching tutorial groups during Winter intensive university classes and PSTs and staff from CTEC schools coming together for a number of Professional Learning programs run by ACU and CEM. The broad scope of these partnership activities suggests that the potential for ongoing and long-term relationships is strong and that mutual benefits for all partners, recognised as critical to sustainable partnerships (Kruger et al. 2009), is highly likely.

50.5.3 Participation in the CTEC Tutorial Group: Benefits of the ‘Cohort’ Experience for PSTs

The results of the interviews with PSTs indicated a positive experience of being part of the CTEC project. Participation in the CTEC specific tutorial group was a highlight. They generally felt a heightened sense of support and a strong feeling of belonging to the tutorial group. The most positive aspect of their involvement in CTEC was the strength of the relationships that they had been able to develop. PSTs saw the ongoing relationships that they were having and hoped to continue having as a result of being in the program as a significant benefit. They also identified the future benefits and continuing opportunities for long-term relationships with each other and with the schools through their involvement in the program. One PST described the experience of being in a tutorial together as a cohort,

“… we’re a really close group now” and “it’s been so much fun.”

Another participant referred to the formation of “good strong relationships” within the tutorial group and felt that in future years they would have “such good support networks”.

When asked to her motivation for getting involved in CTEC, one PST gave this response:

I really like the idea of having like the same cohort of students, like staying with the same class all the way through.

And another PST said:

The familiarity of faces in the university environment is hard to come by so it’s good to have that support network.

When asked to describe the experience of being part of the CTEC tutorial one PST said “definitely fun” and “we all know each other, we can all work together and stuff like that. We all support each other”. The importance of support networks and a sense of belonging have been reported as a benefit of an extended professional experience model (Gutierrez and Nailer 2020).

One of the PSTs discussed how participating in CTEC has benefited her development as a teacher:

Everyone knows each other and it’s very easy to communicate and we have a lot of discussion about our placements… it’s very open so I feel like I’m learning a lot being in the project.

These responses from the PSTs indicate the positive impact of the opportunity to develop long term and ongoing relationships with their peers and with the teaching staff from the University. PSTs have felt a sense of connection and support as a result of being involved in the CTEC tutorial group. The PSTs have identified this as being important to their development as teachers. This is supported by Green et al. (2020) who highlighted the importance of relationships to the success of partnerships. Drawing on the notion of third space the positive impact on PST development can be understood as the way in which the partnership has contributed to helping the PSTs negotiate the complexity of their preservice teacher identity (Forgasz et al. 2018).

The way in which the program has been structured has created the space to develop strong, open relationships. These responses from the PSTs around the value of the relationships that they have developed and expect to continue building resonate with the findings of Le Cornu (2013) into early career teacher resilience. The findings of this research indicated that positive relationships with teaching colleagues were critical to resilience in early career teachers. Positive relationships with peers at other schools were also identified as sustaining for PSTs in this study. The benefit of the partnership at the centre of this research is that the possibility exists for the PSTs and the schools to invest in long term relationships. The partnership aims to have the PSTs in this consortium of schools for all of their professional experience placements over the four years of their degree and then for them to potentially find employment within this group of schools. This means that the PSTs and the schools should feel as if it is worth investing in the relationships as they have the potential to last for a significant amount of time.

50.6 Conclusion

The most widely noted benefits of school-university partnerships for policy-makers, education systems and universities are around the practicum or professional experience placements for PSTs. The idea of partnerships as a panacea in teacher education (Kennedy and Doherty 2012) has been promoted in recent Australian government reports. This chapter explored the perceptions of teachers, principals, PSTs and education system staff of participating in a school-university partnership. The findings from this research project indicate that there is considerable support from participants for school-university partnerships and that they had a willingness and a desire for strengthening those partnerships. The PSTs identified the personal and professional benefits of studying within a cohort of students involved in the partnership. For them it meant an enhanced PST experience now as well as holding the promise of personal and professional relationships in their future teaching careers. For principals, they could see benefits for the PSTs, their current staff in terms of professional learning, and long-term benefits for the future.

The findings from this study suggest an emphasis on the relational aspects of school-university partnerships may be beneficial for ensuring their sustainability. It is this opportunity to develop meaningful relationships over an extended period of time that principals, teachers and pre-service teachers in this study found most appealing about participating in a school-university partnership. Knowledge of the community, rather than just the school was seen as an important aspect of pre-service teacher preparation that focused on developing the skills, knowledge and attributes that would contribute to schools in a particular geographic location.

References

Allard, A., White, S., Mayer, D., Kline, J., Hutchison, K., Loughlin, J., & Dixon, M. (2012). Building effective school-university partnerships for a quality teacher workforce (Final Report). Deakin University.

Allen, J. M., & Wright, S. E. (2014). Integrating theory and practice in the pre-service teacher education practicum. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 20(2), 136–151.

Anagnostopoulos, D., Smith, E., & Basmadjian, K. (2007). Bridging the university-school divide: Horizontal expertise and the “two-worlds’ pitfall”. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(2), 138–152.

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2017). School profile. Retrieved from https://myschool.edu.au/school

Bhabha, H. (1994). The location of culture. London: Routledge.

Brady, L. (2002). School-university partnerships: What do schools want? Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 27(1), 1–9.

Burn, K., Mutton, T., & Hagger, H. (2017). Towards a principled approach for school-based teacher educators: Lessons from research. In M. Peters, B. Cowie, & I. Menter (Eds.), A companion to research in teacher education (pp. 105–120). Singapore: Springer. https://doi-org.ezproxy1.acu.edu.au/10.1007/978-981-10-4075-7_7.

Catholic Education Melbourne. (2014). Enrolment in Catholic schools 2007–2013. Unpublished material.

Clemens, A., Loughran, J., & O’Connor, J. (2017). University coursework and school experience: The challenge to amalgamate learning. In M. A. Peters, B. Cowie, & I. Menter (Eds.), A companion to research in teacher education. Singapore: Springer.

Cozza, B. (2010). Transforming teaching into a collaborative culture: An attempt to create a professional development school-university partnership. The Educational Forum, 74(3), 227–241.

Darling-Hammond, L. (Ed.). (1994). Professional development schools: Schools for a developing profession. New York: Teachers College Press.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Powerful teacher education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Darling-Hammond, L., & Bransford, J. (Eds.). (2005). Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn to do and be able to do. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco.

Engestrom, Y., Engestrom, R., & Karkkainen, M. (1995). Polycontextuality and boundary crossing in expert cognition: Learning and problem solving in complex work activities. Learning and Instruction, 5, 319–336.

Forgasz, R., Williams, J., Heck, D., Ambrosetti, A., & Willis, L. (2018). Theorising the third space of professional experience partnerships. In J. Kriewaldt, A. Ambrosetti, D. Rorrison, & R. Capeness (Eds.), Educating future teachers: Innovative perspectives in professional experience. Singapore: Springer.

Green, C. A., Tindall-Ford, S., & Eady, M. (2020). School-university partnerships in Australia: A systematic literature review. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 48(4), 403–435.

Grudnoff, L., Haigh, W., & Mackisack, V. (2016). Re-envisaging and reinvigorating school university practicum partnerships. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 45(2), 180–193.

Gutierrez, A. (2016). Exploring the becoming of pre-service teachers in paired placement models. In R. Brandenburg, S. McDonough, J. Burke, & S. White (Eds.), Teacher education: Innovation, intervention and impact. Singapore: Springer.

Gutierrez, A., & Nailer, S. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ professional becoming in an extended professional experience partnership programme. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2020.1789911.

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Education and Vocational Training. (2007). Top of the class: Report on the inquiry into teacher education. Canberra: House of Representatives Publishing Unit. Retrieved from http://www.aph.gov.au/house/committee/evt/teachereduc/report/fullreport.pdf.

Jones, M., Hobbs, L., Kenny, J., Campbell, C., Chittleborough, G., Gilbert, A., Herbert, S., & Redman, C. (2016). Successful university-school partnerships: An interpretive framework to inform partnership practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 108–120.

Kennedy, A., & Doherty, R. (2012). Professionalism and partnership: Panaceas for teacher education in Scotland? Journal of Education Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.682609.

Kerosuo, H., & Engestrom, Y. (2003). Boundary crossing and learning in creation of new work practice. Journal of Workplace Learning, 15(8), 345–351.

Kertesz, J., & Downing, J. (2016). Piloting teacher education practicum partnerships: Teaching alliances for professional practice. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41(12), 1–9.

Kruger, T., Davies, A., Eckersley, B., Newell, F., & Cherednichenko, B. (2009). Effective and sustainable university-school partnerships: Beyond determined efforts by inspired individuals. Canberra: Teaching Australia.

Le Cornu, R. (2013). Building early career teacher resilience: The role of relationships. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(4), 1–16.

Le Cornu, R., & Ewing, R. (2008). Reconceptualising professional experiences in pre-service teacher education … reconstructing the past to embrace the future. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 1799–1812.

Martin, S., Snow, J., & Franklin-Torrez, C. (2011). Navigating the terrain of third spaces: Tensions with/in relationships in school-university partnerships. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(3), 299–311.

Mayer, D., Dixon, M., Kline, J., Kostogriz, A., Moss, J., Rowan, L., Walker-Gibbs, B., & White, S. (2017). Studying the effectiveness of teacher education: Early career teachers in diverse settings. Singapore: Springer.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Muller, M. J. (2009). Participatory design: The third space in HCI. In A. Sears & J. Jacko (Eds.), Human computer interaction: Development process. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis.

Norman-Meier, L., & Drake, C. (2010). When third space is more than the library: The complexities of theorizing and learning to use family and community resources to teach elementary literacy and mathematics. In V. Ellis, A. Edwards, & P. Smagorinsky (Eds.), Cultural-historical perspectives on teacher education and development (pp. 196–211). London: Routledge.

O’Doherty, T., & Harford, J. (2017). Initial teacher education in Ireland – A case study. In M. Peters, B. Cowie, & I. Menter (Eds.), A companion to research in teacher education (pp. 167–178). Springer. https://doi-org.ezproxy1.acu.edu.au/10.1007/978-981-10-4075-7_11.

Ord, K., & Nuttall, J. (2016). Bodies of knowledge: The concept of embodiment as an alternative to theory/practice debates in the preparation of teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 355–362.

Rowley, G. (2013). School-university partnerships support pre-service teachers. Research Developments, ACER. https://rd.acer.org/article/school-university-partnerships-support-pre-service-teachers

Ryan, J., & Jones, M. (2014). Communication in the practicum: Fostering relationships between universities and schools. In M. Jones & J. Ryan (Eds.), Successful teacher education: Partnerships, reflective practice and the place of technology (pp. 103–120). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Ryan, J., Butler, H., Kostogriz, A., & Nailer, S. (2016). Advancing partnership research: A spatial analysis of a jointly planned teacher education partnership. In R. Brandenburg, S. McDonough, J. Burke, & S. White (Eds.), Teacher education: Innovation, intervention and impact (pp. 175–191). Singapore: Springer.

Schuck, S. (2013). The opportunities and challenges of research partnerships in teacher education. Australian Educational Researcher, 40, 47–60.

Sleeter, C. (2001). Preparing teachers for culturally diverse schools: Research and the overwhelming presence of whiteness. Journal of Teacher Education, 52(2), 94–106.

Soja, E. (1996). Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group. (2014). Action now: Classroom ready teachers. Retrieved from http://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/action_now_classroom_ready_teachers_print.pdf

Ure, C. (2009). Practicum partnerships: Exploring models of practicum organisation in teacher education for a standards-based profession. Australian Teaching and Learning Council Report.

Walsh, M., & Backe, S. (2013). School-university partnerships: Reflections and opportunities. Peabody Journal of Education, 88, 594–607.

White, S., Tindall-Ford, S., Heck, D., & Ledger, S. (2018). Exploring the Australian teacher education ‘partnership’ policy landscape: Four case studies. In J. Kriewaldt, A. Ambrosetti, D. Rorrison, & R. Capeness (Eds.), Education future teachers: Innovative perspectives in professional experience. Singapore: Springer.

Williams, J. (2014). Teacher educator professional learning in the third space: Implications for identity and practice. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(4), 313–326.

Zeichner, K., Payne, K., & Brayko, K. (2015). Democratising teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 66(2), 122–135.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Nailer, S., Ryan, J. (2021). School-University Partnerships and Enhancing Pre-service Teacher Understanding of Community. In: Zajda, J. (eds) Third International Handbook of Globalisation, Education and Policy Research. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66003-1_50

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66003-1_50

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-66002-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-66003-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)