Abstract

The management algorithm for pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCN) has evolved with rapid advancements in the knowledge of the diagnostic features, natural history and biology of these neoplasms together with the introduction of new and improvement in diagnostic modalities and tests. Over time, the management of PCNs has gradually trended from an aggressive resection approach in the past towards a more conservative approach with surveillance at present. Due to controversy in the management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) especially with regards to branch duct (BD)-IPMN over the past 2 decades, several international consensus guidelines have been formulated to guide clinicians on the management of these neoplasms. These guidelines in general serve 2 main objectives: (1) diagnostic workup and clinical decision making and (2) surveillance protocol including methods, interval and duration. The present consensus guidelines’ are useful in in guiding clinicians in decision making for the management of IPMNs by utilizing widely and easily available clinical parameters and morphological features from conventional cross-sectional imaging. Nevertheless, present guidelines remain far from ideal and are still associated with various limitations.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

53.1 Introduction

Over the past three decades, the management algorithm for pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCN) has evolved with rapid advancements in the knowledge of the diagnostic features, natural history and biology of these neoplasms together with the introduction of new and improvement in diagnostic modalities and tests [1,2,3]. In general, management of PCNs has gradually trended from an aggressive resection approach in the past towards a more conservative approach with surveillance at present [3,4,5]. Today, with the widespread use of cross-sectional imaging; there is an exponential increase in the number of incidental asymptomatic PCNs detected worldwide [3, 4, 6]. However, numerous investigators have demonstrated that the vast majority of these lesions have an indolent nature and a benign natural history [3,4,5,6].

The main pathological types of PCNs are intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN), serous cystic neoplasms (SCN), mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCN) and solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPPN) [7, 8]. At present, it is widely accepted that SCNs are almost universally benign and can be managed conservatively unless they grow to a large size resulting in local compressive symptoms [1, 8]. SPPNs on the other hand are potentially malignant neoplasms which occur in children and young adults especially females and hence, aggressive surgery when technically feasible is almost always warranted [1, 8, 9]. Similarly, surgical resection is usually indicated for MCNs as these premalignant neoplasms usually occur in middle-aged females [10]. Nonetheless, selected cases of small (<4 cm) MCN [8] may be observed especially in older patients with a shorter life-expectancy.

However, unlike the management of SCN, SPPN and MCN; the management approach towards IPMN remains controversial and debatable [1, 5]. Depending on the site of involvement of the pancreatic duct, IPMNs are classified into main-duct (MD), branch-duct (BD) and mixed-duct IPMNs (MT-IPMNs) [11, 12]. At present, there is uniform consensus among experts that most MD-IPMN and MT-IMPNs should be surgically removed due to the high-risk (>50%) of harboring malignancy or progressing to malignancy. On the other hand, most BD-IPMNs can be treated conservatively due to their indolent biology and only selected cases require surgical resection [8, 11, 12]. At present, several clinical and radiological criteria are now widely-accepted and have been well-validated to be associated with malignancy in IPMN. These include parameters such as main pancreatic duct dilatation, larger cyst size, enhancing mural nodule/solid component, positive cytology, pancreatitis, jaundice and elevated serum carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 which are utilized in most management guidelines for IPMN [8, 11,12,13,14].

Due to controversy in the management of IPMNs especially with regards to BD-IPMN over the past 2 decades, several international consensus guidelines have been formulated to guide clinicians on the management of these neoplasms. These guidelines in general serve 2 main objectives: (1) diagnostic workup and clinical decision making and (2) surveillance protocol including methods, interval and duration [1, 15]. In 2006, international experts convened in Sendai and formulated the first widely-accepted expert guidelines for IPMN and MCN which came to be widely known as the Sendai Guidelines (SG06) [11]. SG06 (Table 53.1) was a 2-tier system which proposed that in addition to MCNs; all MD-IPMNs and BD-IPMNs with features such as size >3 cm, symptoms or main pancreatic duct diameter > 6 mm be considered for surgical resection. These guidelines were adopted in clinical practice world-wide for over 5 years but numerous studies subsequently performed to validate the utility of these guidelines [12, 13] demonstrated several major limitations. The main criticism of the guideline was its “over-aggressive” recommendation for surgical resection of BD-IPMN. The SG06 was demonstrated to have a low positive predictive value (PPV) of only about 33% for predicting malignant IPMN and adherence to the guideline resulted in overtreatment of patients whereby many benign BD-IPMNs were resected [16, 17]. The risks associated with the overtreatment of patients with IPMN should not be underestimated as despite advances in pancreatic surgery today, it remains a major operation associated with a significant morbidity and mortality even in high volume centers [16]. Hence, bearing the limitations of SG06 in mind, international experts convened in Fukuoka and proposed a new revised guideline termed the Fukuoka Consensus Guidelines in 2012 (FG12) [12]. Similar to SG06 the FG12 recommended resection for all MCN but revisions were made to the management guidelines for IPMN. The main objective was of the FG12 was to reduce the number of “unnecessary” surgical interventions and overtreatment of BD-IPMN [12].

53.1.1 Fukuoka Guidelines 2012 (Revised 2017)

Unlike the original SG06 guideline, the FG12 was a 3-tier system which categorized IPMNs into high risk, worrisome risk (WRFG12) and low risk groups (Table 53.1) [12]. High risk lesions (HRFG12) were to be managed via surgical resection whereas those which were low-risk could be conservatively managed via close surveillance [12]. The revised guidelines also recognized the role of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) which had been increasingly utilized in the diagnostic evaluation of PCNs. In general, the use of EUS was recommended for IPMNs with WRFG12 although upfront surgical resection could be considered for selected WRFG12 such as young healthy patients with cysts ≥3 cm [12]. Notably, some of the major revisions in the FG12 to highlight was that cyst size ≥3 cm and pancreatic duct dilatation between 5-9 mm were no longer regarded as high risk indications for immediate surgical intervention but were only considered as worrisome risks. Furthermore, the need for enhancement on imaging was included to confirm that a mural nodule/solid component was suspicious as it was recognized that mucin within the cyst could mimic a non-enhancing nodule on cross-sectional imaging [1]. Systematic reviews [17,18,19] summarizing the literature have been performed to evaluate the utility of both the SG06 and FG12 and both guidelines have been shown to be associated with a low PPV but high NPV. Nonetheless, the FCG seemed to have a better PPV than the SCG (47% vs 33%) albeit at the expense of a slightly lower NPV [18].

In 2017, further refinements were made to the FG12 with regards to the management of IPMN (Table 53.1) [16, 20]. This included demoting enhancing mural nodules <5 mm to the WRFG12 and adding features such as elevated Ca 19-9 and cyst growth rate to WRFG12. To date, these revisions remain the most recent updates to the guidelines (FG17) [20].

53.1.2 European Guidelines 2018 (EG18)

The EG18 [8] represents an update to the previous European guidelines published in 2013 [21]. It was formulated by a multidisciplinary expert panel from several European associations and unlike the FG12/17 which focused on IPMN, treatment recommendations for different pathological types of PCNs were included. Of note, whereas the FG12 recommended resection for all MCNs, the EG18 was more conservative than its predecessors and proposed surgical resection only for MCNs with worrying features such as presence of mural nodules or a cyst size >4 cm [8].

Similar to the FG12/17, the EG18 was a 3-tier system (Table 53.1) which classified IPMN into three categories according to the indication for surgery: absolute indication (AIEG18), relative indication (RIEG18) and no indication for surgery (Table 53.1). These were in general very similar to the FG17 with a few notable differences [1]. Upfront resection was recommended for patients in the absolute AIEG18 group like the HRFG17 group. Similarly, patients were conservatively managed in the no indication group like the FG17 low risk group. Notably, for the RIEG18 group, EG18 was more aggressive in proposing upfront surgery. Surgery was recommended for patients without significant comorbidity and 1 RIEG18 and for patients with significant comorbidity and 2/more RIEG18. This differed from the WRFG17 which recommended further investigation via EUS-FNA and to only consider surgery in young healthy patients with cyst ≥3 cm. Unlike FG17, the EG18 also took into account the number of worrisome features and patients’ comorbidities in their recommendations [1].

Several other minor differences between the EG18 and FG17 worth highlighting include the inclusion of new onset diabetes, using a cyst growth rate of ≥5 mm/year rather than 2 years and notably the change in cyst size cut-off from 3 to 4 cm in the RIEG18 [1]. The obvious impact of the change in the size cut-off is that this would result in a larger group of patients which can be managed conservatively via surveillance. However, more studies are needed to confirm if patients with BD-IPMN within the 3 to 4 cm size range can be observe safely. Due to its recency, not surprisingly, there are remain relatively few studies to date [22, 23] validating the EG18. The PPV for HGD/IC of AIEG18 and RIEG1 has been reported to range from 48.3% to 72.7% and 40.5% to 47.4% within the limitations of surgical series’. Of note, the false negative rate for malignancy of the EG18 was reported to be 1.9% [22].

Thus far the 3 guidelines discussed (SG06, FG12/17 and EG18) are the most common guidelines used to date (Table 53.1). In addition to these 3 guidelines, other guidelines less commonly used outside the United States include the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) 2015 guidelines [13] and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2018 guidelines [14] which will not be discussed here. It is interesting to note that the EG18, AGA, ACG were formulated based on the evidence-based GRADE framework [16] whereas the SG06 and FG12 was developed based on expert opinion.

53.1.3 Surgery for IPMN

The objective of surgical resection in IPMN is complete removal of the tumor with negative margins (FG17) [20]. Depending on the tumor location, this may require a proximal or distal pancreatectomy. However, it is important to add that the exact type of resection may not always be easy to determine such as for diffuse type MD-IPMN without a definite focal lesion. This may also be difficult to distinguish from chronic pancreatitis. In such cases, ERCP or EUS may be useful to identify features of IPMN such as visualization of a mural nodule or mucin extrusion from a dilated papilla. A formal pancreatectomy with lymphadenectomy such as a pancreatoduodenectomy, left-sided pancreatectomy or total pancreatectomy should be the standard treatment when surgery is performed for suspected malignancy. However, more limited resections [20, 24] such as enucleation, middle pancreatectomy or spleen-saving pancreatectomy may be considered in selected cases of BD-IPMN when preoperative suspicion of malignancy is low. Frozen section should be routinely performed on parenchyma transection margins [20]. In the event of the presence of invasive cancer or high grade dysplasia at the transection margin, further resection should be performed and all patients should be counselled on the possibility of a total pancreatectomy. The presence of IPMN with low grade dysplasia does not warrant further resection of the margins.

53.1.4 Surveillance for IPMN

Based on present knowledge, all patients with IPMN managed conservatively should continue life-long surveillance (until deemed unfit for surgery) as the risk of progression does not diminish over time. It is also important to be cognizant of the development of concomitant pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma especially in patients with a significant family history of pancreatic cancer and these patients would require more intensive surveillance. Similarly, patients who had undergone complete resection of non-invasive IPMN should undergo life-long surveillance for similar reasons due to the field-change effect associated with IPMN [25].

53.2 Discussion

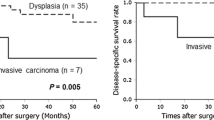

The ideal guideline for the management IPMN should not only identify current risk of harboring HGD or invasive cancer but also future risk of developing malignancy. This would enable early intervention and avoid prolong surveillance. It must be emphasized that patients with IPMN on surveillance should undergo resection before the development of invasive carcinoma due to the poor prognosis of invasive IPMN which is similar to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [26]. It is also imperative to add that an ideal guideline should also avoid surgical overtreatment resulting in unnecessary operations in patients who have little or no risk of developing malignancy during their lifetime [1, 2]. At present, it may be assumed that the optimal timing for surgery in IPMN in most patients would be when lesions harbor HGD as surgical resection will result in cure.

Management of patients with IPMN should be individualized and tailored according to a patient’s risk-benefit profile for surveillance versus resection [1, 27]. In addition to the malignancy risk of the IPMN, other important factors to consider in the clinical decision-making process include the patient’s projected life expectancy which would be determined by his/her age and presence of comorbidities, operative risk which is determined by the type of resection and patient’s overall fitness; and even cost-effectiveness. Unfortunately, most guidelines today do not take into consideration these other important factors other than the recent EG18 which has included presence of comorbidities into the guidelines [1].

The present consensus guidelines’ are useful in in guiding clinicians in decision making for the management of IPMNs. These guidelines utilize widely and easily available clinical parameters and morphological features from conventional cross-sectional imaging [1, 8, 12, 20], However present guidelines remain far from ideal and are still associated with various limitations. More robust scientific evidence is needed to support many of their recommendations [4]. Moreover, the added difficulty in accurately distinguishing IPMN from other PCNs preoperatively, frequently further diminishes the accuracy and hence, utility of these guidelines [1]. Several promising parameters which have been shown to be associated with malignancy in IPMN include inflammatory indices such as neutrophil lymphocyte ratio or platelet lymphocyte ratio [28] and the additive effect of increasing number of worrisome or high risk features on the malignancy risk. These should be considered in future updates of the guidelines [29]. Pathological subtypes of IPMN such as gastric, intestinal and pancreatobiliary subtypes have also been shown to be associated with the malignancy risk of IPMN and may have a major role in future guidelines [30].

Development of novel prognostic nomograms [31, 32] may also enable better prediction of the risk of malignancy of IPMN. The use of these nomograms when coupled with mathematical tools predicting an individual patient’s surgical risk and estimated life expectancy would enable clinicians to determine the most appropriate management option for an individual patient with greater precision.

Moreover, recent advancements in imaging and diagnostic modalities such as confocal laser endomicroscopy [16], micro-forceps biopsy and identification of novel cyst fluid DNA-based, micro-RNA-based or protein-based biomarkers are showing great promise in the future management of IPMN and PCNs in general [4, 16]. Together these developments may potentially be used to improve future IPMN guidelines.

References

Wash RM, Perlmutter BC, Adsay V, Reid MD, Baker ME, Stevens T, Hue JJ, Hardacre JM, Shen GQ, Simon R, Aleassa EM, Augustin T, Eckhoff A, Allen PJ, Goh BK. Advances in the management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Current Prob Surg. 2020.

Goh BK, Tan Y, Thng C, et al. How useful are clinical, biochemical, and cross-sectional imaging features in predicting potentially malignant or malignant cystic lesions of the pancreas? Results from a single institution experience with 220 surgically treated patients. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2008;206(1):17–27.

Goh BK, Tan Y, Cheow PC, et al. Cystic lesions of the pancreas: an appraisal of an aggressive resectional policy adopted at a single institution during 15 years. Am J Surg. 2006;192:148–54.

DiMaio CJ. Current guideline controversies in the management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2018;28:529–47.

Goh BK. International guidelines for the management of pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9833–7.

Heckler M, Michalski CW, Schaefle S, Kaiser J, Buchler MW, Hackert T. The Sendai and Fukuoka consensus criteria for the management of branch duct IPMN – a meta-analysis on their accuracy. Pancreatology. 2017;17:255–62.

Goh BK, Tan DM, Thng CH, Lee SY, Low AS, Chan CY, et al. Are the Sendai and Fukuoka Consensus Guidelines for cystic mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas useful in the initial triage of all suspected pancreatic cystic neoplasms? A single institution experience with 317 surgically treated patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1919–26.

European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas. European evidence-based guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gut. 2018;67:789–804.

Goh BK, Tan YM, Cheow PC, Chung AY, Chow PK, Wong WK, Ooi LL. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: an updated experience. J Surg Oncol. 2007;15(95):640–4.

Goh BK, Tan YM, Chung YF, et al. A review of mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas defined by ovarian-type stroma: clinicopathological features of 344 patients. World J Surg. 2006;30(12):2236–45.

Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17–2.

Tanaka M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183–97.

Vege SS, Ziring B, Jain R, Moayyedi P. Clinical Guidelines committee; American Gastroenterology Association. American gastroenterological association institute guideline on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:819–22.

Elta GH, Enestvedt BK, Sauer BG, Lennon AM. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of pancreatic cysts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:464–79.

Hasan A, Visrodia K, Farrel JJ, Gonda TA. Overview and comparison of guidelines for management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms. World J Gastronterol. 2019;25:4405–13.

Vilas-Boas F, Macedo G. Management guidelines for pancreatic cystic lesions: should we adopt or adapt current roadmaps? J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2019;28:495–501.

Goh BK, Tan DM, Ho MM, et al. Utility of the sendai consensus guidelines for branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:1350–7.

Srinivasan N, Teo JY, Chin YK, Hennedige T, Tan DM, Low AS, Thng CH, Goh BK. Systematic review of the clinical utility and validity of the Sendai and Fukuoka Consensus guideliens for the management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. HPB. 2018;20:497–504.

Goh BK, Lin Z, Tan DM, et al. Evaluation of the Fukuoka Consensus Guidelines for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: results from a systematic review of 1,382 surgically resected patients. Surgery. 2015;158(5):1192–202.

Tanaka M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Kamisawa T, et al. Revisions of international consensus Fukuoka guidelines for the management of IPMN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2017;17:738–53.

Del Chiaro M, Verbeke C, Salvia R, et al. European expert consensus statement on cystic tumours of the pancreas. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:703–11.

Jan IS, Chang MC, Yang CY, Tien YW, Jeng YM, Wu CH, Chen BB, Chang YT. Validation of indications for surgery of European evidence-based guidelines for patients with pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. J Gastronintest Surg. 2019.

Sun L, Wang W, Wang Y, Jiang F, Peng L, Jin G, Jin Z. Validation of European evidence-based guidelines and American College of Gastroenterology guidelines as predictors of advanced neoplasia in patients with suspected mucinous pancreatic cystic neoplasms. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019.

Sauvanet A, Gaujoux S, Blanc B, Couverlard A, Dokmak S, Vullierme MP, et al. Parenchyma-sparing pancreatectomy for presumed noninvasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2014;260:364–71.

Tamura K, Ohtsuka T, Ideno N, et al. Treatment strategy for main duct IPMN of the pancreas based on the assessment of recurrence in the remnant pancreas after resection: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2014.

Koh YX, Chok AY, Zheng HL, Tan CS, Goh BK. Systematic review and meta-analysis comparing the surgical outcomes of invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(8):2782–800.

Goh BK. Sendai consensus guidelines for branch-duct IPMN: guidelines are just guidelines. Ann Surg. 2015;262(2):e65.

Goh BK, Tan DM, Chan CY, et al. Are preoperative blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio useful in predicting malignancy in surgically-treated mucin-producing pancreatic cystic neoplasms. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112:366–71.

Goh BK, Thng CH, Tan DM, et al. Evaluation of the Sendai and 2012 International Consensus Guidelines based on cross-sectional imaging findings performed for the initial triage of mucinous cystic lesions of the pancreas: a single institution experience with 114 surgically treated patients. Am J Surg. 2014;208:202–9.

Koh YX, Zheng HL, Chok AY, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of different histologic subtypes of noninvasive and invasive IPMN. Surgery. 2015;157:496–509.

Jang JY, Park T, Lee S, Kim Y, Lee SY, Kim SW, Kim SC, et al. Proposed nomogrm predicting the individual risk of malignancy in patients with branch duct type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2017;266:1062–8.

Han Y, Jang JY, Oh MY, et al. Natural history and optimal treatment strategy of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: analysis using a nomogram and Markov decision model. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2021;28:131–42.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Goh, B.K.P. (2022). International Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms. In: Makuuchi, M., et al. The IASGO Textbook of Multi-Disciplinary Management of Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Diseases. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0063-1_53

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0063-1_53

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-19-0062-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-19-0063-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)