Abstract

In the context of longitudinal collaborative self-study of teacher education practices (S-STEP), we explore power with as empowerment from relationships and collaboration. We define power-with in self-study as relational strength and capacity; it is generative, fluid, empowering, ecological energy, and space to transform self, practices, knowledge, and culture by broadening and deepening understandings and relationships. Drawing from 9 years of collaborative self-study, we describe how we were invited into S-STEP, constructed a collaborative framework, and created a public homeplace through a process for collaboration that included textualizing lived experiences and enacting a fluid collaborative conference protocol. Positioned as texts, lived experiences became sources for envisionment-building. Together, we read and made meaning from teaching and self-study experiences, over time and through multiple contexts, resulting in shifting paradigms. We created a collaborative space for cross-disciplinary collaboration. In this space, we transformed and re-created a collaborative culture as we navigated personal and professional tensions. Strengthening our individual efficacy and teaching practices lifted us from our academic silos to see and to understand our identities, our practices, and the broader educational landscape in which we teach and research. The collaborative nature of self-study of teaching practices methodology affords the strength of power-with.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

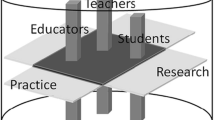

Power, authority, knowledge, and discourse are topics of perennial interest, woven through teacher education literature (e.g., Ball, 1993; Deacon, 2002; McNay, 2004). In this chapter, we consider the relationship between these metaphorical threads in the context of longitudinal collaborative self-study of teacher education practices (S-STEP). As teacher educators who are S-STEP researchers, we have come to understand how critical friendships and public homeplaces grow over time, across places, and through diverse spaces. This chapter highlights the generative and transformative nature of collaborative self-study as a methodology for transforming culture, practices, and self through power-with. Power-with is distinct from power associated with power over. Power over is often characterized as force or control, in a belief that power is finite, and motivated by or resulting in fear, dominance, oppression, and injustice. Power-with is founded upon a commitment to self-awareness, grows out of collaboration and relationships, and is expressed through the journey of embodiment. Power with is power from relationships and collaboration (Kreisberg, 1992). We define power-with in self-study as relational strength and capacity; it is generative, fluid, empowering, ecological energy, and space to transform self, practices, knowledge, and culture by broadening and deepening understandings and relationships.

Empowering others to construct meaningful understanding through educative experiences is the crux of professional learning for educators (Dewey, 1938). In order for teachers to use their knowledge to improve their teaching practice and to create educative experiences for others, they must first construct an understanding as learners themselves. This process of making meaning, as opposed to getting meaning, is dependent on teachers’ opportunity to transact with texts and is aided by communication with and support from a caring community of learners.

We are three female teacher educators and program leaders representing literacy, special education, and educational leadership for a teaching-focused, mid-sized university in the Midwestern United States. Drawing from 9 years of collaborative self-study, in this chapter we describe how we were initially invited into S-STEP, constructed a collaborative framework, and created a public homeplace through a process for collaboration that included textualizing lived experiences and enacting a fluid collaborative conference protocol. Positioned as texts, lived experiences became sources for envisionment-building. Together, we read and made meaning from teaching and self-study experiences, over time and through multiple contexts, resulting in shifting paradigms. We created a collaborative space for cross-disciplinary collaboration. In this space, we transformed and re-created a collaborative culture as we navigated personal and professional tensions. Strengthening our individual efficacy and teaching practices lifted us from our academic silos to see and to understand our identities, our practices, and the broader educational landscape in which we teach and research. The collaborative nature of self-study of teaching practices methodology affords the strength of power-with.

1 Perspectives

Longitudinally, our collaborative self-studies have been situated in transactional reading and learning theory (e.g., Edge, 2011; Dewey, 1938; Dewey & Bentley, 1949; Rosenblatt, 1978/1994; Rosenblatt, 2005) and feminist communication theory (e.g., Belenky et al., 1986, 1997; Colflesh, 1996). Epistemologically, transactional and feminist communication theories recognize the relationship between a knower and their environment, both in what they know and how they communicate that knowledge. Humans share an ecological relationship with their environment—both taking from it and contributing to it (Dewey & Bentley, 1949; Rosenblatt, 2005), much like Gee’s (2008) notion of society as an ambiguous cultural text that is read and composed by its members. The knower, the known, and knowing are aspects of one process (Dewey & Bentley, 1949).

1.1 Feminist Perspectives

Teaching is “intimate work” (Bruner, 1996, p. 86). Professional learning that makes a difference in classroom instruction offers educators opportunities grounded in the complex environment of practice while supporting and nurturing reflections and discourse on their developing knowledge, often termed praxis. From a feminist perspective, care and understanding are at the center of teaching and learning (Noddings, 1984). Like the typically female role of a midwife who helps draw new life from the mother, a teacher recognizes that knowledge is created within and drawn from the learner. Such a theory of knowledge creation is a departure from the more traditional and often male perspective of a banker who deposits knowledge within the learner (Belenky et al., 1986).

Expanding the feminist focus on care and understanding, a framework for women’s ways of knowing grounded our collaborative research. Belenky et al. (1986) advocate for women to become constructivist knowers who see knowledge as actively constructed by all human beings. Constructivist knowers move beyond silent receivers of knowledge and act with a sense of agency. To act with agency, women must gain confidence and skill in using information from a wide range of sources to form their own understandings (Colflesh, 1996).

Teacher learning that improves teaching practice requires not only new knowledge and skills but also new ways of thinking and of seeing oneself. As teachers become confident knowledge constructors, they learn through praxis or trying new practices while seeking to understand why those practices work or do not work. Thus, teachers become researchers who learn new ways to think about and to carry out their work; they become more deliberate and attentive to their instructional decisions (Cohen, 2011). Teachers with a well-developed sense of agency build theory grounded in classroom practice (Bruner, 1996). Through inquiry, they actively formulate questions of importance to them, direct their own investigations, and communicate their newly constructed ideas, thus improving their practice in the process (Liston & Zeichner, 1991).

1.2 Transactional Theory

Transactional theory also suggests that learning occurs when people consider, discuss, and inquire into problems and issues of significance to them (Dewey & Bentley, 1949; Rosenblatt, 1978/1994; Rosenblatt, 2005). Based on this framework, the goal of professional learning for educators would be that they become constructivist thinkers and knowers through reading their own experiences, sharing their interpretations, and expanding those interpretations within a trusted community with the intent of improving their teaching practices.

1.3 Envisionment Building

We also embrace a vision of transformative teaching and learning that is informed by Langer’s envisionment building stances for building understanding (Langer, 2011). An envisionment is “meaning in motion” (p. 17) generated in the act of making meaning, or “the understanding a learner has at any point in time, whether it is growing during reading, being tested against new information, or kept on hold awaiting new input” (pp. 18–19). Meaning-making is potentially ongoing as one learns—confirming, troubling, challenging, and shifting what one knows in light of new meaning-making events. Langer (2011) asserted, “Stances are crucial to the act of knowledge building because each stance offers a different vantage point from which to gain ideas. The stances are not linear; they can and often do recur at various points in the learning process” (p. 22). The five stances Langer identified include: (1) being out and stepping into an envisionment; (2) being in and moving through an envisionment; (3) stepping out and rethinking what one knows; (4) stepping out and objectifying the experience; and (5) leaving and envisionment and going beyond. Langer posits that the stances are a “useful framework for thinking about instruction” (p. 23). Envisionment building stances are also useful for thinking about a narrative inquirer’s orientation to participants’ stories, lived experiences, classroom practices, and professional learning (Edge, 2011, 2021).

Examining how we have enacted 9 years of collaborative self-study, our purpose is to begin to articulate a framework for learning from lived experiences through textualizing (Edge, 2011) critical events (Webster & Mertova, 2007) in a self-study space. We use the term textualize as in “to textualize an experience” to refer to an intentional stance in which a researcher “takes a step back from lived experience and examines it in a way similar to how a reader might objectify a text’s construction, their own reading experience, or their process of understanding a text” (Edge, 2011, p. 330).

2 Creating Collaborative Self-Study

2.1 An Invitation into Self-Study

In 2011, we were new faculty members who were invited to join a group of faculty in our department who had previously conducted collaborative self-study research. We joined as strangers to the group, our university’s culture, and to one another. We were transitioning from our work as K-12 educators into the academy as new assistant professors. The invitation from the existing group served to focus our “desires, understandings, and actions” (Novak, 2009, p. 54) in a manner that appreciated us as individuals and called forth our potential as researchers. It was in this group that we learned about and to do S-STEP in the environment of collaboration aimed to understand and to transform teaching practices and to support one another through living alongside one another as fellow learners and researchers of our lived experiences. After the initial years of our collaborative self-study research group, those members who extended the original invitation began to retire or move-on in other professional directions. We three remained, rooted in the foundation of what those before us had established and what we were learning to embody through our collaborative meaning-making interactions together.

2.2 Constructing a Collaborative Framework

Merging two broad areas of research, feminist and transactional theories, provided the theoretical framework for our work together. This framework created space for each of us to grow and to learn personally and professionally both individually and collectively. In transactional theory, learners are in a state of transaction with their environments including their own knowledge and experiences, sources of knowledge beyond the self, and with other learners. According to Rosenblatt (1978/1994), as readers interpret texts, they are changed by the texts as well as changing the meaning of texts through their interpretations. So learning occurs both from within the learner and from shared interpretations that expand the reader’s questions, connections, and insights. We saw parallels between these two bodies of research and used both perspectives to frame our work together. This early act of constructing a collaborative theoretical perspective, woven through discourse, sharing, and a kind of slow yet purposeful teasing out epistemological perspectives enacted and represented in our histories as learners and teachers during the first year of collaborative self-study enabled us to create a shared perspective for our research together. Together, we aimed to read our experiences as texts so that we could explore possibilities and let our questions and explorations help us better understand and sharpen our interpretations of those experiences.

These theoretical perspectives became the foundation through which processes for learning from lived experiences and learning from and with one another were articulated. We learned to attend to lived experiences and tensions as we captured them as texts to be read and shared. The use of a flexible collaborative conference protocol created a framework for supporting the development of a relationship that allowed us to learn from and with each other within a learning-teaching-research environment we came to call a public homeplace.

2.3 Creating a Public Homeplace

Belenky et al. (1997) describe spaces within which women learn together and move toward constructivist knowing as “public homeplaces” or places where “people support each other’s development and where everyone is expected to participate in developing the homeplace” (p. 13). In public homeplaces, participants feel safe enough to express their thoughts and envision possibilities beyond their current situations. Much as in Close and Langer’s (1995) ideas on “envisionment building” when reading literature (p. 3), as members of a “public homeplace” textualize and share their lived experiences, they begin to “explore the horizons of possibilities” (p. 3). When reading for information, Close and Langer (1995) suggest that the reader “maintains a point of reference” while:

…their envisionments are shaped by their questions and explorations that bring them closer to the information they seek and that help them better understand the topic. As people read, they use the content to narrow the possibilities of meaning and sharpen their understandings of information. Using information gained along the way (combined with what they already know) to refine their understanding, they seek to get the author’s point or understand more and more about the topic. (p. 3)

Although our meeting place, our public homeplace, began as a physical location, a conference room in which we could convene, it became more than a place to meet or even a sociocognitive space to understand our practice; it became a medium for making new meaning; it became a space where we could trust one another to listen without judgment, where we could be safely vulnerable to think out loud, wonder, take safe risks to share ideas as they formed, realizations not yet fleshed out, or share moments of “wobble” (Fecho, 2011, p. 53)—that is, moments of uncertainty when we were teetering between previous assumptions, feelings, or understandings and those that we were in in the process of experiencing. Sharing moments of unfolding understandings or of disequilibrium with the group (McLeod, 2009), and openly considering them together through cross-disciplinary discourse, connections to literature, and others’ insights allowed us the cognitive, social, and emotional space to reform and to transform understandings. Environments benefited from the encouragement of care, authenticity, vulnerability, confidence in the process, and appreciation in one another. The care, intimacy, and insights forged in our collaborative meaning-making shifted the way that we utilized our time together in the homeplace. Initially, we individually prepared to report our progress to the group, much like a faculty member might prepare to share updates to a university committee. However, our collaborative interactions together evolved into a time for us to do the work as we grappled with professional and then, over time, personal, critical events, celebrations, and wonderings together. The expectation of returning to our public homeplace as a place and space to collaborate and make meaning together resulted in a public homeplace as a medium for power-with. We conceptualized our self-study inquiries as multimodal texts, we composed together through discourse in the public homeplace.

2.4 Processes for Collaboration

The creation of a public homeplace was achieved through two distinct, iterative, and intertwined processes: textualizing lived experiences to capture individual perceptions of events in order to share beyond oneself and the collaborative conference protocol as a structure for verbalizing and communicating the often internalized or inchoate tensions in teaching, actively listening to others, offering opportunities to integrate the ideas, connections, and perceptions of others in order to more deeply understand a critical event, a tension, or an artifact from our individual teaching practices.

2.4.1 Textualizing Lived Experiences

We began our first year of self-study with the guiding question of: “What can we learn about our teaching by critically discussing the texts of our teacher education practices?” At the forefront of this research was a focus on the personal and professional tensions and wobbles we experience as teacher educators as a conduit for studying our individual practices. Through this study, we came to view ourselves as active meaning makers who can learn from our teacher education practices as “texts” which we can analyze and discuss with “critical friends” (LaBoskey, 2004, p. 819) through self-study methodology (Cameron-Standerford et al., 2013). We defined text in a broader sense to include the idea that lived experiences once textualized could then be shared, interpreted, reinterpreted, and analyzed. Textualizing our lived experiences and studying them through collaborative self-study methodology, we began to learn how to construct meaningful understanding about our teaching practices.

We embraced the personal and professional tensions identified in our initial study; as a result, we brought professional events to the forefront as we continued. Because of our experiences together exploring personal and professional tensions through self-study, we had built a foundation of mutual respect and safety. We trusted each other to be authentic, candid, and kind and our public homeplace enveloped Tschannen-Moran’s (2013) five facets of trust “benevolence, honesty, openness, reliability and competence” (p. 40). We knew that textualizing (Edge, 2011) our teacher education practices through the envisionment-building stances offered by critical friends in a public homeplace could help us to step back from events, to critically consider them within the broader context of our life histories and professional literature (Cameron-Standerford et al., 2013; Edge, 2021). Making meaning with critical friends about our textualized experiences enabled us to reframe events, consider new details, connections, or vantage points provided by others’ observations and experiences. As a result, we recognized that collaborative self-study is a space in which we could explore, and over time, come to deepen understandings of our teacher education practices (Cameron-Standerford et al., 2016; Edge, 2021). Collaboratively making meaning from textualized teaching events in our public homeplace enabled us to “step back into” an envisionment-building process from the stance of additional knowledge and vantage points—power-with insights, strength, budding confidence, and new wonderings afforded by discourse with critical friends about the texts of our teaching practices.

2.4.2 Collaborative Conference Protocol

Each year, we independently identified a critical event, tension, or artifacts from our lived experiences, formulated a self-study sub-question, and textualized the experience. Individual sub-questions were, at times, in response to a collective inquiry question; other times, the collective inquiry question was shaped from individual questions. This process of forming a shared and individual self-study question was iterative and resulted in both shared and individual commitments to improving practice and constructing understandings.

Through writing, each researcher situated a selected critical event within its broader context, engaged in meaning analysis (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009), and wrote to construct understanding (Richardson, 2000) of what she thought was happening in the critical event she studied. Next, we each orally shared the critical event within a “public homeplace” (Belenky et al., 1997, p. 13) using a flexible collaborative conference protocol (Anderson et al., 2010; Bergh et al. 2018; Cameron-Standerford et al., 2013; Edge et al., 2016; Sidel et al., 1997). The protocol guided us to see and re-see our critical event from multiple perspectives and form a new understanding of practice (Loughran & Northfield, 1998). This protocol included: listening to each individual’s initial analysis of the teaching event and subsequent learning; taking turns saying what we heard or noticed while the individual who had shared quietly took notes; taking turns offering speculative comments, connections, and wonderings; inviting the individual back into the conversation to respond to comments or questions offered by the group or to offer additional details or insights sparked by listening to the group; and writing take-away reflections. Individual take-away statements became a way to attend to the themes developing from our collective work. The data collected included reflective journals; documented decisions during class sessions; conversations with critical friends; anonymous student feedback from course ratings; written and visual artifacts from our teaching and learning experiences; and peer-reviewed artifacts. As researchers, we used extended dialogue to wrestle with ideas. We listened to each other’s ideas carefully and spoke our own emerging ideas, knowing that dialogue allows ideas to clarify, change, and expand. As participants in a public homeplace, we developed self-respect, confidence, and a sense of agency through this process. Textualizing lived experiences (Edge, 2011) helped each researcher develop skills of constructivist knowers as we read our experiences, created new interpretations, and incorporated new insights constructed with critical friends.

The accountability and care of an authentic audience within our public homeplace motivated us and strengthened us through power-with self-study collaborators who returned to our data, who read professional literature, who (re)considered teaching events and tensions in the context of our personal histories, professional landscapes, and unfolding collaborative meaning-making. We created new understandings of practice and visions for possibilities together.

2.5 Strengthening Our Individual Efficacy and Teaching Practices

2.5.1 Personal and Professional Growth

Our first experiences with self-study as a methodology brought to light a commonality across the three of us as we examined our paths to higher education. From the outside looking into academe, our colleagues initially seemed to embody an ideal role of professor and researcher, “university rockstars”—experienced, knowledgeable role models whom we had unknowingly and respectfully othered. Through collaborative self-study, they modeled for us the process of continuously becoming professionals and the vulnerability needed to do the work of self-study. This allowed us to see the possibilities of exploring our own wobbles, led us to study tensions as texts and to see learning and professional identity as ongoing.

Despite feeling individual doubt in our abilities as new researchers and teacher educators, the collaborative nature of self-study research challenged us to re-see ourselves, our experiences, and the trajectory of our professional roles. The process of learning about ourselves and our practices provided us with a sense of agency and resulted in the purposeful exploration of collaboration across educational disciplines. As a result, we did not merely step into an existing university culture to close our doors and go about our work as lone scholars; rather we actively created space, crafted a shared understanding of disciplinary knowledge and language, and sought to build for ourselves as individuals and a collective of three, a new discourse community. Cross-disciplinary critical friends helped to make visible and call into question our, often tacit, knowledge rooted in our disciplines, including discipline-specific language, values, and assumptions. While the value of collaboration in self-study has been widely documented (e.g., Vanassche & Kelchtermans, 2015) for challenging one’s assumptions and biases and for expanding one’s interpretations (LaBoskey, 2004), we have also come to see how a collaborative self-study culture brings to light specific disciplinary foundations that, when articulated and examined amongst critical friends, resulted in transformative teaching practices (Bergh et al., 2018). Over time, we three began to see ourselves as leaders who had much to contribute within our department, the university, and the broader research community.

2.5.2 Strengthening Individual Self-Efficacy

The capacity to improve and grow has not been done in isolation; rather it has been our collaborative community that has helped each of us achieve more personally and professionally than we could have alone. Success brings about feelings of self-efficacy, encourages continued learning, and develops confidence to take risks and reconceptualize professional roles (Ashton, 1984; Elmore & McLaughlin, 1988; Runhaar et al., 2010; Zumwalt, 1988). Our work within self-study as a frame and methodology highlights how our identities have evolved over time as we explored tensions in our personal and professional lives and blurred the compartmentalization of our roles, disciplines, and experiences.

3 Conclusion: Recognizing Collaborative S-STEP as Power-With

As we reflect on the role of collaborative self-study in our professional and personal growth, we identified the developmental nature of the work we have embraced over the last 9 years. This developmental process aligns with our experiences and subsequent belief in self-study as a continuous improvement process rooted in a growth mindset. The nature of self-study methodology “positions the researcher to examine the self as an integral part of the context for learning, whereby the framing and reframing of lived experiences results in a cumulative and altered understanding of practice” (Tidwell et al., 2012, p. 15). Over time questions we asked and data we analyzed shifted outward in relation to our developing agency, awareness, relationships, and experience facilitated through collaborative self-study methodology. Initially, our self-study research began with a focus on our personal selves—that is, our professional identities situated in the context of our broader life experiences as learners, then classroom teachers, and then as teacher educators who studied our individual practices. Our focus broadened out to consider our educational content disciplines, to empower our students, to reach across campus and invite colleagues to participate in transdisciplinary self-study of practice, and to lead through serving within and beyond the S-STEP community. Our knowledge, confidence, relationships, and identity deepened and broadened through collaborative envisionment building.

Collaborative self-study provided an envisionment-building space in which we expected to discover a deeper understanding of our teacher education practices. Our expectation, while subtle, is significant; it reflects our collaboratively constructed stance—our power-with position in relationship to our work as educators. As Bullock (2020) notes, collaborative self-study, if considered lightly, might be perceived as a kind of “echo chamber” where one’s ideas would simply be valued in an effort to reach a simple consensus. Rather, collaborative self-study

...invites critiques from other points of view. Collaborative self-study, grounded in dialogue conceptualized as an interaction between partners, each moving, framing, and reframing their inquiries, is best understood as a dynamic process in which we invite others to extend themselves beyond a comfort zone. (p. 12)

Because of our stance, we positioned ourselves to step into the self-study space and willingly explore our practice through an authentic, vulnerable, and potentially transformative process. It is our dynamic relationship with one another—our friendship—forged from collaborative meaning-making while reframing experiences that empowered us with mutual respect, support, solidarity, influence, and collective action.

Our collaborative, meaning-making experiences enabled us to become purposeful practitioners who examined teaching and S-SSTEP research practices on a deeper level, much more so than what would have been possible if on our own. Collaboration empowered us to transcend the potentially isolated context of our academic silos (Allison & Zain, 2018). There was safety in a collaborative S-STEP space that allowed for vulnerability, encouraged us to take risks, formulate questions, and be open to the critical examination of the decisions we make in our teaching. Learning to see ourselves as self-study researchers, we created an environment—a collaborative homeplace—where we learned about S-STEP as a concept that later developed into a culture. Moving through the envisionment building stances (Langer, 2011), we began to embody S-STEP as something within us, as power within. S-STEP became more than an idea or even a methodology, but also a way of being. Power-with through collaborative self-study generated continuous becoming.

Our public homeplace gave, and continues to give, us a safe space to navigate the academy. It further allows us to turn our gazes from ourselves, from the inward, outward to embrace leadership roles and opportunities in our department, university, and S-STEP communities of practice. We experienced transformation of self, culture, and practice through the developmental process of envisioning, experiencing, and learning collaboratively. Power-with in collaborative self-study served as a kind of zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978) through which we could gradually increase and amplify power to grow our knowledge, identity, efficacy, confidence, relationships, and respect for our own and others’ journeys. As we consider our own learning and growth through collaborative self-study, we now wonder how we might more deliberately frame our work with teacher candidates, practicing teachers, and school administrators around power-with collaboration for the purposes of creating spaces for teachers and their students to grow democratic spaces.

Power-with as strength to transform in collaborative self-study holds implications for teacher educators, teachers, and for social justice. S-STEP and teacher education can be seen as relational (e.g., Kitchen, 2005); enacting power-with through S-STEP research methodology and frameworks for teaching practices is to tap into generative power necessary for democracy, for moving beyond the many silos in which we separate and are separated. Bell (2016) describes social justice as collaboratively reconstructing society in accordance with principles of equity, recognition, and inclusion. “Social justice involves social actors who have a sense of their own agency as well as a sense of social responsibility toward and with others, their society, the environment, and the broader world in which we live (Bell, 2016, p. 3). Power-with can be seen as working toward and enacting social justice through developing agency and a sense of social responsibility with others.

One can learn to become a constructivist thinker in a public homeplace where such thinking is valued and modeled; a public homeplace offers a learning environment in which all members become one among equals and where power is amplified by each and shared among all. Through the synergy of collaborative meaning-making through S-STEP methodology, power-with can grow an individual’s ability to act and develop leadership capabilities, or power to, as well as individual and collective sense of agency, value, and efficacy, or power within. Educators who are constructivist thinkers are more likely to see their students as capable of thinking and constructing new ideas (Belenky et al., 1997) and to foster power to and power within to empower their students to see learning as continual growth through dynamic, symbiotic, and transactional relationships.

References

Allison, V., & Zain, S. (2018). Student and teacher: An interdisciplinary collaborative self-study intersecting physics and teacher education. In D. Garbett & A. Ovens (Eds.), Pushing boundaries and crossing borders: Self-study as a means for researching pedagogy (pp. 417–424). S-STEP.

Anderson, D., Imdieke, S., Lubig, J., Reissner, L., Sabin, J., & Standerford, S. (2010). Self-study through collaborative conference protocol: Studying self through the eyes of colleagues. Teaching and Learning, 24(2), 59–71.

Ashton, P. (1984). Teacher efficacy: A motivational paradigm for effective teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 35(5), 28–32.

Ball, S. J. (1993). Education polity, power relations and teachers’ work. British Journal of Educational Studies, 41(2), 106–121.

Belenky, M. F., Clinchy, B. M., Goldberger, N. R., & Tarule, J. M. (1986). Women’s ways of knowing; The development of self, voice, and mind. Basic Books.

Belenky, M. F., Bond, L. A., & Weinstock, J. S. (1997). A tradition that has no name: Nurturing the development of people, families, and communities. Basic Books.

Bell, L. A. (2016). Theoretical foundations for social justice education. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, D. J. Goodman, & K. Y. Joshi (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Bergh, B., Edge, C., & Cameron-Standerford, A. (2018). Reframing our use of visual literacy through academic diversity: A cross-disciplinary collaborative self-study. In J. Sharkey & M. M. Peercy (Eds.), Self-study of language and literacy teacher education practices across culturally and linguistically diverse contexts (pp. 115–142). Emerald Group Publishing.

Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education. Harvard University Press.

Bullock, S. M. (2020). Navigating the pressures of self-study methodology. In J. Kitchen et al. (Eds.), 2nd international handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education. Springer.

Cameron-Standerford, A., Bergh, B., Edge, C., Standerford, N., Reissner, L., Sabin, J., & Standerford, C. (2013). Textualizing experiences: Reading the “texts” of teacher education practices. American Reading Forum Annual Yearbook [Online]. Vol. 33.

Cameron-Standerford, A., Edge, C., & Bergh, B. (2016). Toward a framework for reading lived experiences as texts: A four-year self-study of teacher education practices. In D. Garbett & A. Ovens (Eds.), Enacting self-study as methodology for professional inquiry (pp. 371–377). Auckland University.

Close, E., & Langer, J. A. (1995). Improving literary understanding through classroom conversation (Eric document no. 462 680). National Research Center on English Learning & Achievement. Retrieved at http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED462680.pdf).

Cohen, D. K. (2011). Teaching and its predicaments. Harvard University Press.

Colflesh, N. A. (1996). Piece-making: The relationships between women’s lives and the patterns and variations that emerge in their talk about school leadership. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University, East Lansing.

Deacon, R. (2002). An analytics of power relations: Foucault on the history of discipline. History of the Human Sciences, 15(1), 89–117.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Dover.

Dewey, J., & Bentley, A. F. (1949). Knowing and the known. Beacon.

Edge, C. (2011). Making meaning with “readers” and “texts”: A narrative inquiry into two beginning English teachers’ meaning making from classroom events. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. (AAT 3487310).

Edge, C. (2021). A teacher educator’s meaning-making from a hybrid “Online Teaching Fellows” professional learning experience: Toward literacy practices for teaching and learning in multimodal contexts. In Information Resources Management Association (Ed.), Research anthology on facilitating new educational practices through communities of learning (pp. 422–455). IGI Global.

Edge, C., Bergh, B., & Cameron-Standerford, A. (2016). Critically reading lived experiences as texts: A four-year study of teacher education practices. American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting.

Elmore, R. R., & McLaughlin, M. W. (1988). Steady work: Policy, practice, and the reform of American education. The Rand Corporation.

Fecho, B. (2011). Teaching for the students: Habits of heart, mind, practice in the engaged classroom. Teachers College Press.

Gee, J. P. (2008). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology and discourses (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Kitchen, J. (2005). Conveying respect and empathy: Becoming a relational teacher educator. Studying Teacher Education, 11(1), 195–207.

Kreisberg, S. (1992). Transforming power: Domination, empowerment, and education. State University of New York Press.

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed.). Sage.

LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. K. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study practices (pp. 817–869). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Langer, J. A. (2011). Envisioning knowledge: Building literacy in the academic disciplines. Teachers College Press.

Liston, D. P., & Zeichner, K. M. (1991). Teacher education and the social conditions of schooling. Routledge.

Loughran, J. J., & Northfield, J. (1998). A framework for the development of self-study practice. In M. L. Hamilton (Ed.), Reconceptualizing teaching practice: Self-study in teacher education (pp. 7–18). Routledge.

McLeod, S. (2009). Simply psychology: Jean Piaget. Retrieved on May 30, 2019 at http://www.simplypsychology.org/piaget.html#adaptation.

McNay, M. (2004). Power and authority in teacher education. The Educational Forum, 68(1), 72–81.

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring. University of California Press.

Novak, J. M. (2009). Invitational leadership. In B. Davies (Ed.), The essentials of school leadership (pp. 53–73). Sage.

Richardson, L. (2000). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 512–529). Sage.

Rosenblatt, L. (1978/1994). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. Southern Illinois University Press.

Rosenblatt, L. (2005). Making meaning with text: Selected essays. Heinemann.

Runhaar, P., Sanders, K., & Yang, H. (2010). Stimulating teachers' reflection and feedback asking: An interplay of self-efficacy, learning goal orientation, and transformational leadership. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(5), 1154–1161.

Sidel, S., Walters, J., Kirby, E., Olff, N., Powell, K., Scripp, L., & Veenama, S. (1997). Portfolio practices: Thinking through the assessment of children’s work. National Education Association Publishing Library.

Tidwell, D., Farrell, J., Brown, N., Taylor, M., Coia, L., Abihanna, R., Abrams, L., Dacey, C., Dauplaise, J., & Strom, K. (2012). Presidential session: The transformative nature of self-study. In J. R. Young, L. B. Erickson, & S. Pinnegar (Eds.), Extending inquiry communities: Illuminating teacher education through self study. Proceedings of the ninth international conference on self-study of teacher education practices (pp. 15–16). Brigham Young University.

Tschannen-Moran, M. (2013). Becoming a trustworthy leader. In M. Grogan (Ed.), The Jossey-Bass reader on educational leadership (pp. 40–54). Jossey-Bass.

Vanassche, E., & Kelchtermans, G. (2015). The state of the art in self-study of teacher education practices: A systematic literature review. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 47(4), 508–528.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Webster, L., & Mertova, P. (2007). Using narrative inquiry as a research method: An introduction to using critical event narrative analysis in research on learning and teaching. Routledge.

Zumwalt, K. K. (1988). Are we improving or undermining teaching? In L. Tanner (Ed.), Critical issues in curriculum (Eighty-seventh yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, Part I) (pp. 148–174). The University of Chicago Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Edge, C.U., Cameron-Standerford, A., Bergh, B. (2022). Power-With: Strength to Transform Through Collaborative Self-Study Across Spaces, Places, and Identities. In: Butler, B.M., Bullock, S.M. (eds) Learning through Collaboration in Self-Study. Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices, vol 24. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-2681-4_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-2681-4_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-16-2680-7

Online ISBN: 978-981-16-2681-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)