Abstract

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) was first described by Aston C Key [1] in 1838 as a disease that causes paraplegia. Two male patients with OPLL suffered from bladder disturbance and paraplegia, followed by septicemia. The autopsies revealed a narrowed cervical canal due to OPLL. However, the condition then went without notice for a long time. Oppenheimer [2] reported 18 cases of calcification or ossification of the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments over 100 years after OPLL was first described by Key. Most of these cases were ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament. He did not recognize the clinical significance of OPLL.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) was first described by Aston C Key [1] in 1838 as a disease that causes paraplegia. Two male patients with OPLL suffered from bladder disturbance and paraplegia, followed by septicemia. The autopsies revealed a narrowed cervical canal due to OPLL. However, the condition then went without notice for a long time. Oppenheimer [2] reported 18 cases of calcification or ossification of the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments over 100 years after OPLL was first described by Key. Most of these cases were ossification of the anterior longitudinal ligament. He did not recognize the clinical significance of OPLL.

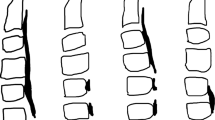

In Japan, a similar case to Key’s was reported in 1960 by Dr. Hirokuni Tsukimoto [3]. A 47-year-old male with finger clumsiness and sensory disturbance in both arms and legs underwent posterior surgery and achieved transient recovery. However, he suffered from pneumonia 3 months after the operation following tetraparesis and pressure sore formation on the sacrum. The autopsy revealed ectopic bone formation adjacent to the vertebral body, which was presumed to have changed from the posterior ligament (Fig. 1.1). The author speculated that the etiology involved repeated minor trauma to the neck, such as whiplash injury, inducing this ectopic bone formation. The author noted that vascular factors are also related to the acceleration of myelopathy. Following this report, many studies have been enthusiastically conducted in Japan.

In 1975, the government launched a research grant to conquer intractable diseases that have continued up to the present. Eight investigation committees have been organized for this disease. Table 1.1 shows the names of the chief researchers of each group and their main topics.

The PLL ossifies spontaneously and increases in length and thickness year by year, resulting in compression of the spinal cord. Minor trauma can easily cause deterioration of paresis or induce spinal cord injury. Although ectopic bone formation in ligamentous tissue has been presumed to occur in association with diabetes mellitus or certain foods and other metabolic diseases, the precise mechanism has remained unclear [4, 5].

Although epidemiology, natural history, diagnosis, and treatment were common topics of each period, the development of imaging techniques, such as CT and magnetic resonance imaging, enabled the addition of new information. Reconstructed CT images of the cervical to lumbar spine can be easily obtained within a few minutes. Such whole-spine reconstructed images indicated that ossification of the yellow ligament in the thoracic and lumbar spine was more frequently observed in patients with cervical OPLL than expected. Moreover, cervical OPLL was detected in males three-times more frequently than in females, but thoracic OPLL showed an opposite trend. Additionally, the ossification of other spinal ligaments, such as the anterior, supraspinal, and yellow ligaments, was observed [6,7,8]. These facts indicate that genetic factors strongly contribute to the development of the ossification of all spinal ligaments. This advancement in imaging also made it easy to evaluate the ossified bone volume in a 3D fashion. Analysis revealed an annual increase in the ossified bone volume and the suppression of ossification after surgical fusion [9, 10]. These studies provide valuable information for the selection of an operative method.

The pathology of ectopic ossification in the spinal ligaments has been studied for a long time. Ossification of the spinal ligaments is ectopic, with hypertrophy of the ligament, proliferation of cartilaginous cells in the ligament, and the release of cytokines related to bone formation (bone morphogenetic protein and transforming growth factor beta) during the ossification process [11]. Recent genetic studies have provided more advanced knowledge of the pathogenesis. A sib-pair study and a genome-wide association study were conducted to identify the susceptibility gene(s) for ectopic bone formation of the spinal ligaments [12, 13]; there were six susceptible loci for OPLL. Ectopic ossification of the spinal ligaments is more likely to develop in middle-aged adults with such genetic factors. The function of some candidate genes has since been studied. This splendid progression in basic research suggests that it is not unreasonable to expect a drug to be available in the future to control the development of ectopic ossification.

Until now, the main treatment for OPLL has been surgery. Many kinds of laminoplasty have been developed in Japan [14, 15]. However, the basic concept of wide and simultaneous decompression of the spinal cord has been mandatory in posterior surgical treatment since the report by Kirita [16]. Anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (ACCF) is also available for this disease. Yamaura’s floating method, in which the ossified ligament is not removed but thinned carefully, has gradually prevailed to avoid intraoperative neurological complications [17]. Comparative studies between these two types of surgery indicated similar outcomes 2 and 3 years postoperatively; however, subsequently, neurological symptoms in patients treated with laminoplasty can deteriorate because of the gradual progression of kyphotic alignment or ossification [18]. The newly proposed K-line is quite useful in the determination of a surgical method. The K-line is defined as the line connecting the midpoints of the spinal canal at the C2 and C7 levels on lateral cervical X-ray examination. When the ossification is large enough to exceed this line toward the spinal cord, anterior surgery will be preferred. The relationship between the ossification and the line depends on the sagittal profile of the cervical spine and the thickness of the ossification [19]. This concept has rapidly prevailed globally in helping to decide on the surgical approach used for each patient.

The concomitant use of posterior instrumentation with laminoplasty was recently proposed to avoid alignment changes [20]. Fusion of the spinal segments may also suppress ossification development. Thus, surgical fusion with either an anterior or posterior approach could help to maintain a good outcome over the long term in the treatment of this disease [21,22,23].

For thoracic OPLL, laminectomy with posterior instrumentation has become popular [24]. Prospectively collected data from multiple spine centers nationwide have shown that abnormal wave changes occurred in more than 40% of cases. Although most of the patients showed spontaneous recovery until the end of the surgery, some of them remained paralyzed postoperatively. The cause of this critical complication is presumed to be not a technical problem but due to the prone position during surgery [25].

Above all, recent progress in this area has been achieved by great support from governmental research grants. Most of these results were obtained by the collaboration of nationwide spine centers and the research committee organized by the Japanese Orthopaedic Association. Details of the studies are available in this textbook.

References

Key GA. On paraplegia depending on the ligament of the spine. Guys Hosp Rep. 1839;3:17–34.

Oppenheimer A. Calcification and ossification of vertebral ligaments (spondylitis ossificans ligamentosa): roentgen study of pathogenesis and clinical significance. Radiology. 1942;38:160–73.

Tsukimoto H. A case report-autopsy of the syndrome of compression of the spinal cord owing to ossification within the spinal canal of the cervical spine (in Japanese). Nihon Geka Hokan (Arch Jpn Chir). 1960;29:1003–7.

Akune T, Ogata N, Seichi A, Ohnishi I, Nakamura K, Kawaguchi H. Insulin secretory response is positively associated with the extent of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1537–44.

Okano T, Ishidou Y, Kato M, Imamura T, Yonemori K, Origuchi N, Matsunaga S, Yoshida H, ten Dijke P, Sakou T. Orthotopic ossification of the spinal ligaments of Zucker fatty rats: a possible animal model for ossification of the human posterior longitudinal ligament. J Orthop Res. 1997;15:820–9.

Mori K, Imai S, Kasahara T, Nishizawa K, Mimura T, Matsusue Y. Prevalence, distribution, and morphology of thoracic ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in Japanese: results of CT-based cross-sectional study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(5):394–9.

Fujimori T, Watabe T, Iwamoto Y, Hamada S, Iwasaki M, Oda T. Prevalence, concomitance, and distribution of ossification of the spinal ligaments: results of whole spine CT scans in 1500 Japanese patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016;41(21):1668–76.

Hirai T, Yoshii T, Iwanami A, Takeuchi K, Mori K, Yamada T, Wada K, Koda M, Matsuyama Y, Takeshita K, Abematsu M, Haro H, Watanabe M, Watanabe K, Ozawa H, Kanno H, Imagama S, Fujibayashi S, Yamazaki M, Matsumoto M, Nakamura M, Okawa A, Kawaguchi Y. Prevalence and distribution of ossified lesions in the whole spine of patients with cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament a multicenter study (JOSL CT study). PLoS one. 2016;11(8):e0160117.

Katsumi K, Watanabe K, Izumi T, Hirano T, Ohashi M, Mizouchi T, Ito T, Endo N. Natural history of the ossification of cervical posterior longitudinal ligament: a three dimensional analysis. Int Orthop. 2018;42(4):835–42.

Ota M, Furuya T, Maki S, Inada T, Kamiya K, Ijima Y, Saito J, Takahashi K, Yamazaki M, Aramomi M, Mannoji C, Koda M. Addition of instrumented fusion after posterior decompression surgery suppresses thickening of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;34:162–5.

Kawaguchi H, Kurokawa T, Hoshino Y, Kawahara H, Ogata E, Matsumoto T. Immunohistochemical demonstration of bone morphogenetic protein-2 and transforming growth factor-beta in the ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992;17(3 Suppl):S33–6.

Karasugi T, Nakajima M, Ikari K, Genetic Study Group of Investigation Committee on Ossification of the Spinal Ligaments, Tsuji T, Matsumoto M, Chiba K, Uchida K, Kawaguchi Y, Mizuta H, Ogata N, Iwasaki M, Maeda S, Numasawa T, Abumi K, Kato T, Ozawa H, Taguchi T, Kaito T, Neo M, Yamazaki M, Tadokoro N, Yoshida M, Nakahara S, Endo K, Imagama S, Demura S, Sato K, Seichi A, Ichimura S, Watanabe M, Watanabe K, Nakamura Y, Mori K, Baba H, Toyama Y, Ikegawa S. A genome-wide sib-pair linkage analysis of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. J Bone Miner Metab. 2013;31(2):136–43.

Nakajima M, Takahashi A, Tsuji T, Karasugi T, Baba H, Uchida K, Kawabata S, Okawa A, Shindo S, Takeuchi K, Taniguchi Y, Maeda S, Kashii M, Seichi A, Nakajima H, Kawaguchi Y, Fujibayashi S, Takahata M, Tanaka T, Watanabe K, Kida K, Kanchiku T, Ito Z, Mori K, Kaito T, Kobayashi S, Yamada K, Takahashi M, Chiba K, Matsumoto M, Furukawa K, Kubo M, Toyama Y. Genetic Study Group of Investigation Committee on Ossification of the Spinal Ligaments, Ikegawa S. A genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. Nat Genet. 2014;46(9):1012–6.

Ogawa Y, Toyama Y, Chiba K, Matsumoto M, Nakamura M, Takaishi H, Hirabayashi H, Hirabayashi K. Long-term results of expansive open-door laminoplasty for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1:168–74.

Seichi A, Takeshita K, Ohishi I, Kawaguchi H, Akune T, Anamizu Y, Kitagawa T, Nakamura K. Long-term results of double-door laminoplasty for cervical stenotic myelopathy. Spine. 2001;26:479–48.

Kirita Y. Posterior decompression for the cervical spondylosis and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in cervical spine (in Japanese). Geka (Surgery). 1976;30:287–302.

Yamaura I, Kurosa Y, Matuoka T, Shindo S. Anterior floating method for cervical myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(359):27–34.

Sakai K, Okawa A, Takahashi M, Arai Y, Kawabata S, Enomoto M, Kato T, Hirai T, Shinomiya K. Five-year follow-up evaluation of surgical treatment for cervical myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: a prospective comparative study of anterior decompression and fusion with floating method versus laminoplasty. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37(5):367–76.

Fujiyoshi T, Yamazaki M, Kawabe J, Endo T, Furuya T, Koda M, Okawa A, Takahashi K, Konishi H. A new concept for making decisions regarding the surgical approach for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: the K-line. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(26):E990–3.

Chen Y, Guo Y, Lu X, Chen D, Song D, Shi J, Yuan W. Surgical strategy for multilevel severe ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament in the cervical spine. (2001). J Spinal Disord Tech. 2011;24(1):24–30.

Koda M, Mochizuki M, Konishi H, Aiba A, Kadota R, Inada T, Kamiya K, Ota M, Maki S, Takahashi K, Yamazaki M, Mannoji C, Furuya T. Comparison of clinical outcomes between laminoplasty, posterior decompression with instrumented fusion, and anterior decompression with fusion for K-line (−) cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(7):2294–301.

Yamazaki M, Mochizuki M, Ikeda Y, Sodeyama T, Okawa A, Koda M, Moriya H. Clinical results of surgery for thoracic myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: operative indication of posterior decompression with instrumented fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(13):1452–60.

Yoshii T, Egawa S, Hirai T, Kaito T, Mori K, Koda M, Chikuda H, Hasegawa T, Imagama S, Yoshida M, Iwasaki M, Okawa A, Kawaguchi Y. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing anterior decompression with fusion and posterior laminoplasty for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. J Orthop Sci. 2020;25(1):58–65. pii: S0949-2658(19)30073-9

Matsumoto M, Chiba K, Toyama Y, Takeshita K, Seichi A, Nakamura K, Arimizu J, Fujibayashi S, Hirabayashi S, Hirano T, Iwasaki M, Kaneoka K, Kawaguchi Y, Ijiri K, Maeda T, Matsuyama Y, Mikami Y, Murakami H, Nagashima H, Nagata K, Nakahara S, Nohara Y, Oka S, Sakamoto K, Saruhashi Y, Sasao Y, Shimizu K, Taguchi T, Takahashi M, Tanaka Y, et al. Surgical results and related factors for ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament of the thoracic spine: a multi-institutional retrospective study. Spine. 2008;33(9):1034–41.

Imagama S, Ando K, Takeuchi K, Kato S, Murakami H, Aizawa T, Ozawa H, Hasegawa T, Matsuyama Y, Koda M, Yamazaki M, Chikuda H, Shindo S, Nakagawa Y, Kimura A, Takeshita K, Wada K, Katoh H, Watanabe M, Yamada K, Furuya T, Tsuji T, Fujibayashi S, Mori K, Kawaguchi Y, Watanabe K, Matsumoto M, Yoshii T, Okawa A. Perioperative complications after surgery for thoracic ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament: a Nationwide multicenter prospective study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2018;43(23):E1389–97.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Okawa, A. (2020). History of Research. In: Okawa, A., Matsumoto, M., Iwasaki, M., Kawaguchi, Y. (eds) OPLL. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-3855-1_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-3855-1_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-3854-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-3855-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)