Abstract

The magnitude and challenges of opporunistic fungal infections is formidable and ever increasing. The magnitude of the problem is very high in Asian countries due to tropical climatic conditions in majority of Asian countries where fungi easily thrieve, compromise in healthcare, misuse of antibiotic and steroid. The emerging multidrug resistant Candida auris infection has been recorded in many Asian countries. In India, a multi-center intensive care unit (ICU) acquired candidemia study, C. auris candidemia had been recorded at 5.3% of all candidemia cases. Many unique features have been recorded in the epidemiology of opportunistic infections. Even the less morbid patients in hospitals acquire opportunistic fungal infections much earlier and spectrum of agents causing infection is much wider. Though immunosuppressed patients are more susceptible to opportunist fungal infections, new risk groups like diabetes, chronic renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and post-H1N1 influenza are recognized. Aspergillus flavus is more common than A. fumigatus in some of the patient groups. The incidence of mucormycosis is very high in China and India especially in patients with uncontrolled diabetes. Isolated renal mucormycosis in apparently healthy individual is an intriguing disease in Asia. Apophysomyces variabilis, Rhizopus microsporus, R. homothallicus, and Rhizomucor variabilis are the emerging agents among Mucorales.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

-

Multidrug resistant Candida auris infection is an emerging threat in tertiary care hospitals in Asia.

-

The infection has been reported from Japan, South Korea, Singapore, China, India, Pakistan, Kuwait, and Qatar.

-

The burden of opportunist fungal infections is much higher in Asian countries compared to developed countries due climatic condition, over-capacity patient population in hospital, compromise in healthcare, misuse/abuse of antibiotic and steroids.

-

Limited studies show distinct epidemiology of opportunist mycoses in this continent, which warrant to have more studies in each country to know local epidemiology.

-

New species and new susceptible hosts for opportunist fungal infections demand awareness campaign among clinicians and development of competent diagnostic mycology laboratories in Asian countries.

-

The incidence of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis and mucormycosis is very high in those countries.

-

Availability and affordability of antifungal drugs are major challenges in management of opportunist fungal infections.

1 Introduction

Systemic fungal infections are caused by pathogenic fungi, which can adapt human body. Pathogenic fungi are few. Majority of the fungi remain as saprobes and do not cause human infections as they fail to grow at 37 °C and resist low redox potential in tissue. However, some of those saprobes can cause infections when the host is compromised either in immunity or due to co-morbidities. Those organisms are called opportunist that utilizes the opportunity offered by weakened defense of host to inflict damage. However, this distinction of pathogens and opportunists is getting blurred with the adaptation of more fungi on host and acquisition of virulence. Further, the global warming allows number of saprobe fungi to overcome the temperature restriction zone between host and environment. Simultaneously the understanding of host immunity clarifies that fungi may not necessarily require overt immunosuppression of host to cause invasive disease; specific defect in signal transduction pathway (like CARD 9, STAT 1) may make the host susceptible for fungal infections [1]. Underlying illness or risk factors for opportunistic fungal infections include human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, hematological malignancies undergoing chemotherapy, hematopoietic stem cells and solid organ transplant recipients, burns, prematurity, and patients having indwelling devices. However, the spectrum of susceptible hosts has increased in recent years. Opportunistic fungal infections have been recorded in patients with post-influenza episode, chronic liver failure, diabetes, and obstructive pulmonary disease and staying in intensive care units (ICUs) [2].

Among opportunistic fungal infections invasive candidiasis is commonest disease, followed by aspergillosis and mucormycosis. Cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and talaromycosis are important in patients with HIV/AIDS. With the change of epidemiology many new fungi are gaining importance to cause infections in compromised hosts and those include Fusarium, Scedosporium, dematiaceous fungi, and many rare fungi. We are facing the following challenges due to emergence of rare fungi causing human infections [3, 4]:

-

Epidemiology of those infections is not well understood with regard to environmental reservoirs, modes of transmission, and ways to detect them.

-

Because of their relative rarity, laboratory diagnosis of these potential pathogens is challenging.

-

Specific identification requires expertise.

-

In vitro Antifungal susceptibility testing is difficult to perform without standard methodology, and antifungal breakpoints are not available. It is therefore difficult to choose appropriate antifungal therapy.

-

Quality-assured diagnosis requires reference laboratories.

-

Reference laboratory facilities are not available in all regions and countries.

The epidemiology and disease burden of opportunistic fungal infections are well studied and estimated in Western world, but the picture in Asian countries is largely unknown due to lack of study, awareness, and adequate diagnostic laboratory facilities. The available limited data indicate high incidence and unique epidemiology of opportunistic mycoses in this region due to large population at risk, broad spectrum of fungal agents, and distinct clinical entities [5, 6]. Separate chapters in the book deal with systemic and opportunist fungal disease under different risk groups. This chapter summarizes the present status of opportunist fungal infections in Asia among patients in general (Table 4.1).

1.1 Incidence/Prevalence

The global estimates indicate >700,000 cases of invasive candidiasis, >200,000 cases of invasive aspergillosis, >220,000 cases of cryptococcosis in HIV/AIDS, ~500,000 cases of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, ~100,000 cases of disseminated histoplasmosis occurring annually [6]. Though such estimates are not available in Asian countries, invasive candidiasis and mucormycosis rate appear very high in this region [7,8,9] and it relates to large patient load, compromise in healthcare, unabated construction activities in the hospital without covering the site from patient area, and largely tropical environment that helps fungi to thrive [7, 10,11,12].

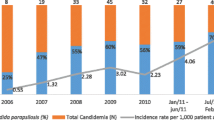

A comparison of incidence of candidemia shows 1 to 12 cases/1000 admission in India [7] compared to 0.05 to 0.36/1000 admission, 0.8/1000 discharges, and 0.2–0.5/1000 discharges in Australia [13], United States [14], and European countries [15, 16], respectively; this means that the rate of candidemia in India is 20–30 times higher as compared to the developed world. In a cross-sectional study at 25 tertiary care centers of six Asian countries, the overall incidence of candidemia was 1.22 episodes per 1000 discharges and varied among the hospitals (range 0.16–4.53 per 1000 discharges) and countries (range 0.25–2.93 per 1000 discharges) [17]. Neonatal candidemia rate was ~46 cases/1000 admission in a tertiary care center in North India, which is nearly three times higher than the incidence reported by National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance in the USA. Multi-center prospective study on ICU acquired candidemia covering 27 ICUs across India, reported 6.5 candidemia cases/1000 ICU admission [8].

Similarly, a very high incidence of mucormycosis has been reported in diabetics (1.6 cases/1000 diabetics) from India [18]. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis is most common presentation. In one center, gastrointestinal mucormycosis has been reported at a rate of 20% of all operated cases of enterocolitis in neonates [19]. All cases autopsy data reported mucormycosis at the rate of 0.6% (23% of all invasive fungal infections) in India (personal communication with Dr. Ashim Das, Professor of Pathology at our Center) which is six times higher than national registry from Japan [20]. Analyzing the reported literature and development of a computational model, the prevalence rate of mucormycosis was estimated at 0.14 cases per 1000 population in India, which is 70 times higher than the incidence of western world [21].

However, such projected data is not possible for invasive aspergillosis as reported case series are limited. A recent multi-center ICU data from India reported 9.5 cases of invasive mold infection per 1000 ICU admission and majority are due to invasive aspergillosis [22]. All cases autopsy data from our center reflects invasive aspergillosis at a rate of 1% (42% of all invasive mycosis). Though majority cases of invasive aspergillosis are known to occur in immunosuppressed patients, 6–14% of Indian patients are apparently immunocompetent especially with clinical presentation of central nervous system aspergillosis, endophthalmitis, and invasive fungal rhinosinusitis [23]. Post-tuberculosis chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) is a common disease in Asian countries and significantly higher than other continents. Among Asian countries, the highest burden of CPA is from India (209,147) followed by Pakistan (72,438), Philippines (77,172), and Vietnam (55,509) [6].

Before AIDS era, the prevalence of cryptococcosis was nearly equal in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients. The balance shifted to immunosuppressed patients with the advent of AIDS. Cryptococcosis is the second most common AIDS defining illness in Chiang Mai Province of Thailand and has been reported at a rate of 1–2% of HIV infected population. Despite the availability of generic fluconazole and highly active antiretroviral therapy, the incidence of cryptococcosis has not decreased substantially in Asian AIDS population. The reason may be poor affordability and compliance to therapy [5].

Pneumocystis pneumonia is a well-known disease in patients with AIDS. Though HIV infection is a major public health problem in Asian Countries, the reported incidence of pneumocystis pneumonia is not as high as developed countries. This low to moderate incidence may be due to difficulty to diagnose this infection rather than actual low prevalence of the organism in this geographical region [24]. A rise in talaromycosis and histoplasmosis cases was recorded during HIV epidemic in restricted geographic regions of Asia. However, the incidence is going down with the introduction of antiretroviral therapy [25].

Many emerging fungi caused outbreaks in Asian countries. Several unusual yeast species (Pichia anomala, P. fabianii, and Kodamaea ohmeri) were isolated in outbreaks in India affecting large number of patients [26, 27]. C. africana, a cryptic species of C. albicans, has recently been reported to cause infection in China [28]. Trichosporonosis due to multidrug resistant Trichosporon asahii is frequently encountered in China, India, Japan, Taiwan, and Thailand [29, 30]. Other uncommon yeasts reported from Asia include Geotrichum, Malassezia, Rhodotorula, and Saccharomyces species [30, 31]. The emergence of multidrug resistant C. auris is the latest threat in Asia. It started from Japan in 2009, spread to South Korea, then India and Pakistan. The infection is also reported from China and Singapore [32, 33]. The magnitude of the infection can only be accessed from the study conducted in India covering 27 ICUs. C. auris accounted for 5.3% of 1400 Candida blood isolates [8]. Saccharomyces fungemia related to use of probiotics has raised concern in critically ill patients of India [34]. Among the black fungi, Cladophialophora bantiana is an emerging fungus in Asia and causes brain abscess even in immunocompetent patients. More than 50% cases reported from the world are from Asia, especially India [35].

1.2 Risk Factors/Underlying Illness

Considerable variations of underlying disease/risk factors have been observed in opportunistic mycoses from Asian countries. In the hospitals, outbreaks have been reported due to sub-optimal hospital care practices and contaminated environment [26, 36], whereas outbreaks in the community is related to spurious practices by untrained healthcare providers [37]. Easy availability of antibiotics and steroids over the counters, intravenous drug abuse, and contaminated infusion bottles contribute further in the rise of these infections [7]. Other than classical risk factors like hematological malignancies, transplant recipients, and immunosuppressive therapy, opportunistic fungal infections are also recorded in critically ill patients with tuberculosis, chronic liver failure, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, and renal failure. Invasive aspergillosis is also recorded in patients with H1N1 influenza infections [38]. Nearly 10–14% of the patients with opportunistic fungal infections have no predisposing factor. The risk factors for opportunistic fungal infections are tabulated in Tables 4.2 and 4.3. During the suppression of cell-mediated immunity (HIV infection) cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, pneumocystis pneumonia, and mucosal candidiasis are prevalent, while in neutropenic patients (hematological malignancies under chemotherapy, transplant recipients) invasive candidiasis, aspergillosis, and mucormycosis are common diseases. Invasive candidiasis and aspergillosis may be seen occasionally in patients with AIDS when CD4 count goes <50 cells/cm and neutropenia develops [2, 5].

1.2.1 Spectrum of Agents

The spectrum of fungal agents causing opportunistic fungal infections has widened in Asia over the years. Many new agents have been reported only from this continent. The spectrum varies from other continents and even between the countries in Asia. Among Candida species causing invasive candidiasis, the prevalence of infections caused by C. albicans drastically has come down in certain countries like India, though it is still >40% in 13 of 25 tertiary care centers studied in six countries in Asia [17]. C. tropicalis is commonest species in India, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and the countries situated in tropical region. In ICU study in India, 31 yeast species were found to cause fungemia [8]. Besides, multidrug resistant C. auris is an emerging species in many Asian countries. The major challenge is that those rare Candida species can not be identified by phenotypic methods commonly practiced in laboratories in Asian countries [32]. Contrary to A. fumigatus, A. flavus is the commoner agent causing infection in some of the Asian countries [23]. Though Aspergillus spp. are the common mycelial fungi causing infection in critically ill patients, in a recent multi-center study mucormycosis has been recorded in 24% of invasive mold infections [22]. Among Mucorales, R. arrhizus is the commonest species isolated. Apophysomyces variabilis, R. microsporus, R. homothallicus, and Rhizomucor variabilis are the emerging agents in Asian countries [22, 38,39,40]. The details of the fungal species prevalent in Asian countries are provided in Table 4.1. Like other countries, antifungal resistance to Candida spp. is evolving. Even azole resistance has been noted in so-called susceptible C. albicans and C. tropicalis [8]. However, azole resistance in A. fumigatus is still not a major problem in Asian countries [41].

2 Conclusions

Opportunistic fungal infections are serious problem in the management of immunocompromised and seriously ill patients in Asian countries. While managing a patient with systemic infection, a low threshold to include opportunistic fungal infections in differential diagnosis is desirable due to its high incidence in those countries. Study on local epidemiology is essential, as the risk factors and spectrum of agents vary in those countries. The available literature shows several unique features in epidemiology of opportunistic mycoses in Asian countries: a) high incidence, b) high yeast carriage rate in the hands of healthcare providers, c) high fungal spore burden in the air in the vicinity of susceptible patients, d) emergence of new risk factors, e) systemic fungal infections even in apparently healthy hosts, f) unique spectrum of etiological agents and resistance pattern. The epidemiology also indicates the need of adequate understanding of disease, source limitation, and early diagnosis to control opportunistic fungal infections in Asian countries.

References

Vaezi A, Fakhim H, Abtahian Z, Khodavaisy S, Geramishoar M, Alizadeh A, Meis JF, Badali H. Frequency and geographic distribution of CARD9 mutations in patients with severe fungal infections. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2434.

Richardson MD. Changing patterns and trends in systemic fungal infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56(Suppl 1):i5–i11.

Perfect JR. Fungal diagnosis: how do we do it and can we do better? Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(Suppl 4):3–11.

Perusquía-Ortiz AM, Vázquez-González D, Bonifaz A. Opportunistic filamentous mycoses: aspergillosis, mucormycosis, phaeohyphomycosis and hyalohyphomycosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:611–21.

Slavin MA, Chakrabarti A. Opportunistic fungal infections in the Asia-Pacific region. Med Mycol. 2012;50:18–25.

Bongomin F, Gago S, Oladele RO, Denning DW. Global and multi-National Prevalence of fungal diseases—estimate precision. J Fungi. 2017;3:57.

Chakrabarti A, Chatterjee SS, Shivaprakash MR. Overview of opportunistic fungal infections in India. Nippon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi. 2008;49:165–72.

Chakrabarti A, Sood P, Rudramurthy SM, Chen S, Kaur H, Capoor M, Chhina D, Rao R, Eshwara VK, Xess I, Kindo AJ, Umabala P, Savio J, Patel A, Ray U, Mohan S, Iyer R, Chander J, Arora A, Sardana R, Roy I, Appalaraju B, Sharma A, Shetty A, Khanna N, Marak R, Biswas S, Das S, Harish BN, Joshi S, Mendiratta D. Incidence, characteristics and outcome of ICU-acquired candidemia in India. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:285–95.

Kaur H, Chakrabarti A. Strategies to reduce mortality in adult and neonatal candidemia in developing countries. J Fungi. 2017;3:E41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3030041.

Kumar S. Batra R. a study of yeast carriage on hands of hospital personnel. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2000;43:65–7.

Huang YC, Lin TY, Leu HS, Wu JL, Wu JH. Yeast carriage on hands of hospital personnel working in intensive care units. J Hosp Infect. 1998 May;39(1):47–51.

Chakrabarti A, Chatterjee SS, Rao KLN, Zameer MM, Shivaprakash MR, Singhi S, Singh R, Varma SC. Recent experience with fungaemia: change in species distribution and azole resistance. Scand J Infect Dis. 2009;41:275–84.

Chen S, Slavin M, Nguyen Q, et al. Active surveillance for candidemia, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1508–16.

Hajjeh RA, Sofair AN, Harrison LH, et al. Incidence of bloodstream infections due to Candida species and in vitro susceptibilities of isolates collected from 1998 to 2000 in a population-based active surveillance program. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1519–27.

Almirante B, Rodríguez D, Park BJ, et al. Epidemiology and predictors of mortality in cases of Candida bloodstream infection: results from population-based surveillance, Barcelona, Spain, from 2002 to 2003. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1829–35.

Arendrup MC, Fuursted K, Gahrn-Hansen B, et al. Seminational surveillance of fungemia in Denmark: notably high rates of fungemia and numbers of isolates with reduced azole susceptibility. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4434–40.

Tan BH, Chakrabarti A, Li RY, Patel AK, Watcharananan SP, Liu Z, Chindamporn A, Tan AL, Sun PL, Wu UI, Chen YC. Asia fungal working group (AFWG); Asia fungal working group AFWG. Incidence and species distribution of candidaemia in Asia: a laboratory-based surveillance study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:946–53.

Bhansali A, Bhadada S, Sharma A, et al. Presentation and outcome of rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis in patients with diabetes. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:670–4.

Patra S, Vij M, Chirla DK, et al. Unsuspected invasive neonatal gastrointestinal mucormycosis: a clinicopathological study of six cases from a tertiary care hospital. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2012;17:153–6.

Yamazaki T, Kume H, Murase S, et al. Epidemiology of visceral mycoses: analysis of data in annual of the pathological autopsy cases in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1732–8.

Chakrabarti A, Sood P, Denning D. Estimating fungal infection burden in India using computational models: Mucormycosis burden as a case study [poster number 1044]. Presented at the 23rd ECCMID conference. Berlin. Germany; April. 2013:27–30.

Chakrabarti A, Kaur H, Savio J, et al. Epidemiology and clinical outcomes of invasive mould infections in Indian Intensive Care Units (FISF study). J Crit Care. 2019;51:64–70.

de Armas Rodríguez Y, Wissmann G, Müller AL, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in developing countries. Parasite. 2011;18:219–28.

Chakrabarti A, Slavin MA. Endemic fungal infections in Asia-Pacific region. Med Mycol. 2011;49:337–44.

Chakrabarti A, Singh K, Narang A, et al. Outbreak of Pichia anomala in the pediatric service of a tertiary care center in northern India. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1702–6.

Chakrabarti A, Rudramurthy SM, Kale P, Hariprasath P, Dhaliwal M, Singhi S, Rao KL. Epidemiological study of a large cluster of fungaemia cases due to Kodamaea ohmeri in an Indian tertiary care Centre. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O83–9.

Hu Y, Yu A, Chen X, Wang G, Feng X. Molecular characterization of Candida africana in genital specimens in Shanghai, China. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:185387. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/185387.

Miceli MH, Díaz JA, Lee SA. Emerging opportunistic yeast infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:142–51.

Liao Y, Lu X, Yang S, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of Trichosporon Fungemia: a review of 185 reported cases from 1975 to 2014. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:ofv141.

Wirth F, Goldani LZ. Epidemiology of Rhodotorula: an emerging pathogen. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2012;2012:465717.

Cortegiani A, Misseri G, Fasciana T, Giammanco A, Giarratano A, Chowdhary A. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, resistance, and treatment of infections by Candida auris. J Intensive Care. 2018;6:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-018-0342-4.

Tan YE, Tan AL. Arrival of Candida auris fungus in Singapore: report of the first 3 cases. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2018;47:260–2.

Roy U, Jessani LG, Rudramurthy SM, Gopalakrishnan R, Dutta S, Chakravarty C, Jillwin J, Chakrabarti A. Seven cases of Saccharomyces fungaemia related to use of probiotics. Mycoses. 2017;60:375–80.

Chakrabarti A, Kaur H, Rudramurthy SM, Appannanavar SB, Patel A, Mukherjee KK, Ghosh A, Ray U. Brain abscess due to Cladophialophora bantiana: a review of 124 cases. Med Mycol. 2016;54:111–9.

Chowdhary A, Becker K, Fegeler W, et al. An outbreak of candidemia due to Candida tropicalis in a neonatal intensive care unit. Mycoses. 2003;46:287–92.

Gupta A, Gupta V, Dogra MR, et al. Fungal endophthalmitis after single intravenous administration of presumably contaminated dextrose infusion fluid. Retina. 2000;20:262–8.

Chakrabarti A, Das A, Mandal J, et al. The rising trend of invasive zygomycosis in patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. Med Mycol. 2006;44:335–42.

Diwakar A, Dewan RK, Chowdhary A, et al. Zygomycosis—a case report and overview of the disease in India. Mycoses. 2007;50:247–54.

Chakrabarti A, Singh R. Mucormycosis in India: unique features. Mycoses. 2014;57(Suppl 3):85–90.

Prakash H, Ghosh AK, Rudramurthy SM, Singh P, Xess I, Savio J, Pamidimukkala U, Jillwin J, Varma S, Das A, Panda NK, Singh S, Bal A, Chakrabarti A. A prospective multicenter study on mucormycosis in India: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Med Mycol. 2018;57:395. https://doi.org/10.1093/mmy/myy060.

Arikan-Akdagli S. Azole resistance in Aspergillus: global status in Europe and Asia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1272:9–14.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Chakrabarti, A. (2020). Epidemiology of Opportunist Fungal Infections in Asia. In: Chakrabarti, A. (eds) Clinical Practice of Medical Mycology in Asia. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9459-1_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9459-1_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-9458-4

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-9459-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)