Abstract

Teacher education programs frequently have explicit courses and structures designed to prepare teachers for increasingly diverse social contexts. This chapter explores the value and inherent challenges experienced in employing pedagogies based on Boal’s (Theater of the oppressed. (trans: McBride, C., & McBride, M.). New York: Urizen, 1979, Games for actors and non-actors. New York: Routledge, 2003) Theater of the Oppressed (TO) with pre-service teachers. It begins with a review of social justice teacher education within the self-study literature as well as the unique value of arts-based approaches within self-study teacher education practices to promote social justice. We then offer examples of how we, as teacher educators, engaged in self-studies in the context of an arts-based student teacher seminar employing TO practices and how TO contributed to both the authors’ and students’ insights related to diversity, power dynamics, and cultural frames of reference. The challenges faced in using TO in teacher education are then examined for the lessons they offer teacher educators.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Self-study

- Teacher education

- Theater of the Oppressed (TO)

- Social justice

- Forum Theater

- Image Theater

- Embodied practices

Introduction

I perceived being oppressed and feeling silenced by my mentor teacher during my first seven-weeks of student teaching. (Mandy, a Caucasian, mid-career changer, student teaching in a 5th grade classroom including African-American, Latino, Asian, and white students)

I talked to the students about English being my second language and how much more I would know in Chinese. (Lan, a young Chinese immigrant woman student teaching in a 4th grade classroom including African-American, Korean-American, and white students)

Teacher educators around the world are seeking ways to support teachers like Lan and Mandy whose linguistic and cultural backgrounds differ substantially from those of their students. Recent years have witnessed an ongoing increase in immigration which in turn has transformed the demographic population of teachers as well as the students they teach. In addition, there has been a rise in nontraditional teacher population – that is individuals coming into the teaching profession as a second or a third career (Olsen 2010). Such changes have caught the interest of education researchers and scholars who have been studying about issues of multiculturalism and diversity including its impact on the emotions and challenges that traditional and nontraditional teachers experience today in the context of ever-changing demographics.

We are mid-career teacher educators working in a private liberal arts university in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. The question that arose for us, two teacher educators/researchers working within a certification program at the undergraduate and graduate level, was how we might use an embodied practice such as Theater of the Oppressed (TO) to engage student teachers like Mandy and Lan to further explore issues of power, privilege, and oppression. How might we engage them in critical conversations to understand their assumptions and cultural frames and imagine possibilities and new ways to interrupt and change the oppressive patterns and behaviors in self and/or institutions and communities? In addition, how might we use the learnings from our work to further our craft of using TO activities as teacher educators to create a socially just teacher education program?

In this chapter, we first provide an overview of the review of social justice teacher education within the self-study literature followed by an overview of the use of arts-based approaches within self-study teacher education practices to promote social justice teacher education. We then discuss one specific arts-based approach, namely, TO, as a tool for exploring issues of power, privilege, and oppression within a teacher education program. Finally, we highlight ways of addressing challenges of using TO within a socially just teacher education program and draw implications for future self-study research.

Part 1: Review of Social Justice Teacher Education Within Self-Study Literature

Across the landscape of self-study in teacher education, there is a shared urgency and passionate concern for issues of equity and social justice (Cochran-Smith and Lytle 2004; Hamilton and Pinnegar 2015; Kitchen et al. 2016; LaBoskey 2015). Topics related to diversity and diversity issues (including cultural, economic, racial, and gender) have been on the forefront in professional meetings (e.g., AERA, SSTEP) as well as in written academic materials such as journals, reports, etc. Specific to self-study of teacher education, attention to these issues has increased, as was called for in the last International Handbook of Self-Study in Teacher Education (2004). The distinct value of self-study of teacher education research in bringing about more democratic and equitable teacher practice was cited by many who reflected on its history (Brown 2004; Griffiths et al. 2004; Schulte 2004). These authors further cited the need for increased focus on issues of social justice in the professional knowledge generated in self-study of teacher education research. A review of titles, abstracts, and keywords in Studying Teacher Education, a journal of self-study of teacher education practices, revealed that between its inception in 2005 and 2010, 14% of articles are specifically referred to issues related to diversity or other terms related to social justice (multiculturalism, poverty, urban education, race, sexual orientation, etc.). Between 2011 and 2014, the average percentage of articles addressing social justice issues within self-study research was 23.5%, and in the volumes from 2015 and 2016, the percentage had grown to 47 of included articles explicitly naming topics related to the broad category of social justice.

Tidwell and Fitzgerald’s (2006) professional learning text Self-Study and Diversity collected self-study research of teacher education with equity and access as focal issues. They explicitly acknowledge the responsibility of teacher educators to address the diversity and access issues inherent in schooling. They reflect that a central theme across self-studies addressing diversity was transformation through active learner engagement in both the pre-service in-service teachers being taught and the teacher educators carrying out the self-studies. Indeed, teacher educators engage in self-study with the explicit hope that new insight and shifts in perspective will influence their practice (Loughran 2002; Zeichner 2007). Brown (2004), in the International Handbook of Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices , noted a paucity of attention to issues of social justice in the self-study literature despite the growing body of educational research evidence for the powerful influence of teacher attitudes and beliefs on the culturally competent and just practice of educators. She notes that the methods, goals, and dispositions inherent in self-study distinctively align with the “messiness” and complexity of self-reflection in regard to our biases, prejudices, or limiting constructions with regard to race and class. She cites the contributions of the self-study literature at that time along with a call for further work in social justice self-study.

It is through self-reflective inquiries carried out by educators whose dispositions embrace an open-minded, wholehearted, responsible approach to the teaching-learning process that we have gained an understanding of the race and class meanings that are embedded in their self-constructions and relationships with students, in the curricular texts and educational programs designed, and in educators’ forms of resistance to social justice and transformative curricular design. It is through these self-studies that we may continue to gain insights into the particular ways in which the normalization of inequity manifests itself throughout the educational system, gain an understanding of probable means of intervention, based on the unique histories of the persons and institutions with which we are involved, and gain a profound understanding of the theoretical implications that this local work has for educational practice and hence, for teacher education. (Brown 2004, p. 568)

Brown (2004) calls self-study researchers to attend to this challenging work as a way to contribute to the democratic transformation of education at both the personal and institutional level. Griffiths et al. (2004) also appeal for more attention to issues of social justice in the self-study of teacher education. The authors took a dialogic approach in their exploration of self-study researchers’ willingness (and unwillingness) to take on the work of developing professional knowledge specific to social justice issues. The authors’ dialogue reveals the emotional complexity and perceived risk of this work, and they delineate the value of telling and listening to little, personal stories which serve to counter, disrupt, and critique the broader societal educational narratives and professional knowledge.

Schulte (2004) addressed the role of self-study in the development of professional knowledge in multicultural teacher education toward the goal of preparing teachers for diverse settings. She cites critical reflection about values and beliefs as a key to the teacher educator’s transformative process through self-study. She sees the knowledge derived through self-studies from both the individual view of the teacher educator and the view of teacher preparation programs as important contributions to the professional knowledge related to preparation of teachers for diverse settings. Schulte, along with the other handbook authors (Brown 2004; Griffiths et al. 2004), call for the self-study research community to increase attention to issues of social justice, diversity, and multicultural understandings to promote a more socially just world. Their work laid the groundwork for an expanded body of self-study research, as well as the methodological standard to include the cultural, racial, and socioeconomic contexts where self-studies are situated and a grounding in the ethic of care and social justice in self-study practice and research (LaBoskey 2004, 2009; Pinnegar and Hamilton 2009).

While issues related to diversity are gaining more visibility in national and international forums, Zembylas and Chubbuck’s (2012) work remind us that grappling with diversity on a day-to-day basis has an immediate impact on the emotional lives of the teachers. These researchers assert that working in diverse classrooms creates additional emotional demands on the teachers.

The tensions that teachers, including student teachers, experience between knowing and being, theory and practice, and the technical and existential are dialogic relationships that are “produced because of social interaction, subject to negotiation, consent, and circumstance, inscribed with power and desire” (Britzman 2003, p. 26). For many teachers, these tensions produce negative emotions such as anger, anxiety, and fear and cause a state of exhaustion, hopelessness, or powerlessness that can impact their effectiveness and satisfaction with teaching (Bloomfield 2010; Britzman 2007; Merryfield 2000; Nias 1996; Olsen 2010), as well as their decisions, actions, and reflections (Zembylas 2005). Many times these tensions are held within one’s body. Thus, teaching is complicated, emotional, interpersonal, and an embodied experience that is often important to the development of the emerging teacher identity. Like Sutton (2005) and Zembylas and McGlynn (2012), we believe that helping teachers to cope with the emotions of negotiating increasing multiculturalism is as valuable as helping them to learn the (academic) tools they will need to work in diverse and multicultural classrooms. Thus, in socially just teacher education programs, emotions play an important role in realizing or disrupting inequities.

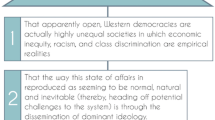

The focus of social justice education is wide and varied. Some theorists/educators focus more on examining and challenging underlying structures (Apple 2000; Freire 1998), while others like Nieto (2004) and Souto-Manning (2011) emphasize the role of cultural identity. Bakhtin (1981) and Foucault (1984), on the other hand, examine ways in which the use of language privileges some groups while marginalizes others. Like Freire (2004), Zembylas and Chubbuck (2012) note the power of emotions to motivate transformative actions toward building a more humane and socially just society. All of these approaches reveal different aspects of oppression and thus are points of intervention. Thus, in this chapter, we see the purpose of social justice education is to (a) enable teachers to develop habits of heart and mind that are necessary for critically examining issues of power, privilege, internal and external oppression, and their own socialization within oppressive systems (Boal 2003, 2006); (b) allow teachers to engage in critically interrogating their own emotion-laden beliefs, examining privileged positions of power and socialized ways of seeing and being in the world (Zembylas and Chubbuck 2012); and (c) foster imagination to look for openings and possibilities and promote a sense of agency to interrupt and change the oppressive patterns and behaviors in self and/or institutions and communities to which they belong to create a more socially just world (Greene 1995; Hinchion and Hall 2016; Hooks 1994; Zembylas and McGlynn 2012).

Arts-Based Approaches Within Self-Study Teacher Education Practices to Promote Social Justice Teacher Education

Given the abstract and deeply internal nature of the self-directed explorations described in the process of self-study related to issues of social justice, we turn to the unique value of arts-based approaches to make visible the invisible under examination in this emotionally complex work. Weber and Mitchell (2004) suggest several key features that make visual artistic modes particularly valuable for the representation of self-study research. Several of the cited features include reflexivity, capturing the ineffable, holistic communication, revealing the universal in the particular, making the familiar strange, embodiment, accessibility, and making the personal social and more activist. The marriage of arts-based approaches to self-study has undergone thorough examination as many self-study researchers now employ these methodologies in their work (Mitchell et al. 2013; Samaras 2009, 2010). This chapter seeks to consider a particular performative pedagogy, Boal’s (1979, 2003) Theater of the Oppressed (TO), as a valuable arts-based tool for transformation and wholehearted exploration of limiting beliefs and expanded perspectives.

Placier et al. (2008) described the value of using TO within social justice teacher education. They noted developing teachers’ expanded awareness of diversity and power issues in the work of teaching. Further, they found participants described the tools and vocabulary for problem posing and perspective-taking useful. Despite the resistance from students, engaging in the TO work with students resulted in improved attitudes and multicultural understandings in the program over time.

Published self-studies incorporating TO methodologies are small in number. Cockrell et al. (2002) engaged in a self-study collaboration explicitly seeking to discover the value of TO activities with pre-service teachers in achieving the desired outcomes in a course on teaching for democracy and social justice. Despite evidence of some expanded awareness of diversity, the authors’ primary insights are related to the students’ resistance to the TO activities. Bhukhanwala (2012) noted her learning from a self-study of her application of TO in a student teaching seminar. She noted that the activities offered opportunities to engage with developing teachers in critical conversations about their own cultural frames and how self-reflection through the TO activities enabled new awareness and agency in responding to challenging dilemmas. She also reflected on the important role the TO facilitator plays in shaping the conversation toward important underlying beliefs and cultural frames at the core of the Boalian underpinnings of the work and not getting caught up in the teacherly advice trap when teachers presented their real-life student teaching dilemmas from their classrooms. Forgasz and Berry (2012) presented a self-study exploring the potential of Boal’s Rainbow of Desire as an enacted practice employed collectively by a teacher education faculty for reflection and professional development. They explored the potential of this TO activity as a tool for self-study and reflected that it “appears to offer a useful means of surfacing the problematic (via the enactment of an oppression) and seeing into, interpreting, and reframing experience (through employing a variety of viewpoints)” (p. 108). Additional and closely related self-study has explored various embodied pedagogies in teacher education contexts (Forgasz et al. 2014; Forgasz and McDonough 2017; McDonough et al. 2016).

Boal (2003, 2006) and Jordi (2011) assert that due to socialization and institutional practices, individuals often participate in the world in mechanized ways, and as a result, the human body is a site for feelings and oppression. Therefore, one part of social justice education includes becoming aware of one’s habituated ways of being and acting in this world. Embodied participation in arts-based practices has the ability to engage our aesthetic sensory capacities, awaken our senses, and (re)activate our imagination to look for possibilities – imagine what could otherwise be (Lawrence 2012; Greene 1995; Pagis 2009). Authentic engagement with embodied practices (such as the arts) offers an aesthetic space for us to tap into embodied emotions and embodied knowing – which concerns knowledge that may not be yet present in our conscious mind (Butterwick and Lawrence 2009; Forgasz 2014). Researchers like Forgasz and McDonough (2017), Lawrence (2012), and Satina and Hultgren (2001) assert that embodied knowing triggers affective knowing (emotions), which in turn triggers cognitive knowing. It is in the telling and retelling of our embodied lived experiences and/or our silenced voices through the arts (and other embodied and contemplative pedagogies) as individuals and as collectives that we make visible our thoughts and feelings. Furthermore, in listening to our experiences and those of others, we begin to deepen our inquiry and explorations of our lived experiences and imagined possibilities (Bhukhanwala 2007; Bhukhanwala and Allexsaht-Snider 2012; Bhukhanwala et al. 2016; Cahnmann and Souto-Manning 2010; Estola and Elbaz-Luwisch 2003; Forgasz 2014; Harman and French 2004). Like Butterwick and Lawrence (2009), we too argue that incorporating embodied learning and art forms (specifically TO) into a critical discourse fosters deeper learning and creates an aesthetic space for transformative learning. We define arts-based practice as a practice that employs a systematic use of artistic processes, the making of artistic experiences to illuminate, revel, understand, and examine lived experiences (Eisner 2008; Cole and Knowles 2008).

The process of effecting a change in one’s frame of reference by critically examining those assumptions, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings that may be divisive/alienating and moving toward a more inclusive, self-reflective experience is what Mezirow (1997) refers to as transformative learning . Drawing from the work of Cranton and Taylor (2012), Dirkx (2001), Kroth and Cranton (2014), Mezirow (1998), and Mezirow and Taylor (2011), we define transformative learning as a shift that emerges from awareness that stems from critically reflecting on one’s emotions and on a disorienting experience. The awareness (explicit and/or implicit) offers new possibilities that could allow for creating more open and inclusive ways of thinking and being in this world.

Part 2: Theater of the Oppressed: A Theoretical and a Practical Resource

A specific embodied and an arts-based tool that we have used within social justice education is Theater of the Oppressed. TO is not entirely a new pedagogy for self-study researchers. Forgasz and Berry (2012) published a self-study on teacher educators’ own participation in Boal’s Rainbow of Desire. They concluded that Boal’s Rainbow of Desire technique engaged participants in a reflective practice and self-study by challenging their taken-for-granted assumptions and by integrating multiple perspectives they were able to look at their practice in new ways. Forgasz and colleagues (2012, 2014, & 2017) have published widely on the value of using embodied pedagogies as a reflective practice. Placier and colleagues have also studied the use of TO in teacher education (Burgoyne et al. 2005, 2007; Cockrell et al. 2002; Placier et al. 2005a, b, 2008). They have written extensively about their use of TO with student teachers at their university in Midwestern United States to support their students’ development of socially just ideals and their understanding of costs and privileges of diversity including self-study-focused projects. They highlight the value of building a culture of trust among the participants when exploring sensitive topics using TO activities.

Our work with creating spaces for social justice education in teaching and teacher education is also informed by Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed (1979). This approach is grounded in the work of Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970) and creates a safe aesthetic space for people to come together, rehearse for reality, and restore dialogue (Bhukhanwala 2007; Bhukhanwala and Allexsaht-Snider 2012; Boal 2003, 2006; Cahnmann and Souto-Manning 2010; Harman and French 2004). Furthermore, participation in Boalian Theater could provide student teachers with a tool that they could effectively use to engage in empathy and perspective-taking for understanding their students’ perspectives and strengthening their relationships with their students and others (Bhukhanwala and Allexsaht-Snider 2012).

From a Boalian approach, active engagement and imagination can be realized in the aesthetic space. For Greene (1995), aesthetic spaces allow students and teachers to imagine as a way of engaging in empathy and perspective-taking: “It is becoming a friend of someone else’s mind” (p. 38). Within this approach, theater is a reflection of daily activities, serving the function of bringing a community together for celebration, entertainment, and dialogue (Blanco 2000), as well as for posing problems and generating multiple possibilities, which can become stepping stones into different ways of thinking and acting (Popen 2006). Within aesthetic spaces, we dramatize our fears, give shape to our thoughts/perceptions, and rehearse our actions for the future. We “make possible imaginative geographies, in which opportunities for transitive knowing are freed up” (Popen 2006, p. 126) and transformative learning can occur.

Critical performance pedagogies such as Theater of the Oppressed can promote transformative learning by “giving voice to people, awakening the soul, and creating space for action, both privately and publicly” (Merriam and Kim 2012, p. 65). More specifically, the participants are involved in “identifying issues of concern, analyzing current conditions and causes of a situation, identifying points of change, and analyzing how change could happen and/or contributing to the actions implied” (Prentki and Selman 2000, p. 8). The reflexive and embodied nature of this approach allows us to understand the experiences in deeper and newer ways, imagine possibilities, and rehearse for future actions (Butterwick and Lawrence 2009).

Thus, we assert that in Boalian activities, teachers, through embodied participation, create a theatrical dialogue to interrogate their habituated ways of seeing and being in the world, the oppressive systems, and their socialization practices within these systems, voices, beliefs, and emotions that are silenced and finally to imagine ways to interrupt, change, and transform. Next we introduce the context of our research on TO in teacher education. Several of the core practices regularly employed are described, and examples of our self-study of this practice are shared.

Context of Our Research Using Theater of the Oppressed Within a Teacher Education Program

Our broader study was situated in a teacher education program in a liberal arts university in the mid-Atlantic United States. The undergraduate and graduate student teachers participated in a voluntary, supplemental seminar during their student teaching semester. In this chapter, we draw on data from the five arts-based student teaching seminars that were offered on a semester basis over 2 years. The group size for each seminar ranged from 4 to 12 participants, featuring a blend of undergraduate and graduate level student teachers in the areas of early childhood, elementary, and special education, as well as dual certification (a combination of these areas of education). The participants were between the ages of 22–50 and included traditional undergraduate, graduate, and nontraditional career-changing pre-service teachers. The undergraduate students were earning their bachelors in education, while the graduate students had a wide range of backgrounds (e.g., Radio/TV/Film, Physical Therapy, Liberal Arts, Communications, Business, etc.). Two teacher educators (Foram and Kim) co-facilitated these seminars. Over the 5 semesters, a total of 34 student teachers participated in this study, 11 at the undergraduate level and 23 at the graduate level. Of these, 33 student teachers were females and 1 student teacher was a male. The ethnic makeup of the group included 30 Caucasians, 3 African-Americans, and 1 Asian student teacher.

Seminar Activities

The seminar met bi-weekly, and activities were developed in response to student-generated themes and issues of dilemmas identified in their student teaching contexts. Each week included warm-up games and other active norm setting and trust/community building. Of the many techniques that Boal has developed, in our work, we have used and will share some details about the following: Theater Games, Image Theater, and Forum Theater.

Theater Games

The games that we often employ are selected from Games for Actors and Non-Actors by Boal (2003). After an explanation and a demonstration, we all play the game and then stop to debrief. The purpose of these theater games is to provide varying structures to bring the developing teachers’ lived experiences into our teacher education classroom for playful analysis, reflection, and reimagination. Games serve to create a shared, novel sensory experience which enlivens the senses and provides developing teachers’ valuable shared data to be unpacked and reframed outside of the traditional language-based model of learning. As an example, we share our adaptation of a Boalian game titled “Walk” that we have often used in our work.

Walking often is a mechanized movement, and though we have our own individual gait, walking often alters according to place and the roles we play. Becoming aware of our walking can be a way in which one can get in touch with one’s inner thoughts and feelings and those of others. In facilitating this game, the joker (facilitator) asks the group to come to the center of the room and invites them to walk around in circles, lines, or in a pattern they desire but in a way that would not cause them to bump into someone else and hurt them. The specific prompts we use are as follows: walk like yourself, walk when in a hurry, walk in a garden, walk like a teacher in your school, walk as a principal in your school, walk as a child you adore in your present classroom, walk like a child you have difficulty connecting with in your present classroom, and walk like a teacher you would like to be.

At the end of the activity, we take a few minutes to debrief and share what we became aware of through our participation in this embodied activity. The student teachers often share some of their metacognitive thoughts related to things they took for granted or things that may have become mechanical to them in their world. The awareness leaves them with a deeper understanding of themselves, others, and the influence of power in their relationships.

Forum Theater

The third Theater of the Oppressed activity that we will describe is called Forum Theater. In this activity, the teachers are invited to bring in the dilemmas they are facing in the classroom which are then enacted in a role-play format. After the role-play is initially enacted, the spectators (other prospective teachers in the audience) are invited to enter into the role-play to try out possible interventions and become spect-actors. The active spect-actors use this aesthetic theatrical space to rehearse interventions that they could consider using later in real life (Boal 2003). We play the role of joker (facilitator), who after each role-play invites the spect-actors (student teachers) to enter the role-play and enact their strategy. The spect-actors accept or reject the solution based on what feels right to them. In the final step, the participants reflect on the rehearsed strategies and try the strategies in the real world of their classrooms. The purpose of Forum Theater is to generate many possible solutions and engage the participants in critical thinking (Boal 2003) creating a self-repeating model.

Foram’s Vignette: Jokering in a Social Justice Teacher Education Program

The vignette presented here highlights the teacher educator’s experience of Jokering (facilitating) Forum Theater with pre-service teachers and the pedagogical insights she gained from examining her own practice.

For the self-study inquiry, Foram invited Kim to play the role of a critical friend. Kim was a co-facilitator of the student teaching seminars. As a result she shared an understanding of the context and experience and had ample opportunities to observe Foram in the seminar meetings. As noted in self-study literature, critical friends provide a supportive and a nurturing environment to allow for both intellectual and emotional learning (Clark 2001; Kitchen et al. 2008; Samaras 2010). The specific data sources for the inquiry were as follows: videotapes of all the seminar meetings which were reviewed to examine Foram’s practice of facilitation of Boalian Theater activities; ongoing post-session notes from conversations with Kim, who served as a critical friend; transcribed interviews with student participants; and personal reflections on facilitations. The data were analyzed using open and axial coding (Strauss and Corbin 1998) to identify themes, categories, and properties.

Like other Boalian activities, in Forum Theater activities, the Joker plays an important role. Fundamental to Boal’s theatrical process is a facilitator, someone who keeps things moving (Schutzman 2006), someone who takes responsibility for logical running of the TO activities (Cahnmann and Souto-Manning 2010), and someone who both supports the participants and raises critical questions to engage the spect-actors in critical thinking (Osterlind 2011). Boal refers to this person as the “joker,” in reference to the wild card in a deck of cards. Just like the joker in a deck of cards, a TO joker can also assume a role as needed, “sometimes director, sometimes referee, sometimes facilitator, sometimes leader” (Linds 2006, p. 122), and sometimes spect-actor, engaging in a discourse of posing questions, examining social structures, and generating possibilities (Boal 2003; Schutzman 2006).

In Forum Theater presentations, Boal typically played the role of the director, facilitator, and critic (Boal 2006). After generating multiple possible interventions to the same situation, Boal asked the spect-actors to consider if the intervention were real, could it happen? By asking such questions, Boal engaged with the spect-actors to challenge and problematize any overly simplified solutions that had been offered. Through the processes of generating possibilities and examining the “realness” of the solutions, the TO participants engaged in a “rehearsal for revolution” (Boal 1979, p. 155).

On examining her role, Foram learned that as a teacher educator, she too wore multiple hats in her classroom that included taking responsibility for the logistical decisions of TO activities; selecting TO structures to work with; supporting, inviting, and engaging students (including those who were shy and tentative); addressing the audience by posing questions to examine the situation and realness of the solutions; and jumping in to “spect-act” when appropriate.

During the seminars, many of the student teachers brought to light the challenges they experienced with student(s) in their elementary classrooms. In posing these challenges, they often raised issues around classroom management and searched for strategies that could help them to “fix” the behaviors of their students. Foram often noticed an absence of the critical perspective in exploring these tensions despite having been exposed to these ideologies in their coursework. She wondered about the role she could play as a teacher educator in helping students to develop a critical lens and supporting them as they critically examine their assumptions and cultural frames in making sense of diversity. It was through the ongoing process of debriefing with Kim that she reflected on her assumptions and recognized that somewhere she was taking for granted that the students could automatically engage in critical reflections. She came to see the value of including explicit and intentional questions that could have the potential to engage the students in critical reflections.

Taking this awareness into her classroom as a TO Joker, she generated a series of questions that she could use to engage her students in critical reflections: What happened in the enactment? What are the power relations among the characters? What type of relationship does this protagonist establish with the antagonist in this scene? What could be the protagonist’s thoughts and feelings? What could be the antagonist’s thoughts and feelings? How does this scene end? What other strategies could possibly lead to a different outcome, especially an outcome that could be more humane and democratic and would establish an open channel of communication?

We next share an example of a Forum Theater activity that illuminates Foram’s role as a joker in promoting critical reflections on examining one’s assumptions and cultural frames in understanding difference.

Why can’t they just be quiet? Jessica∗ (a pseudonym), a Caucasian student teacher teaching a diverse group of second-grade students in a suburban school district, came to one seminar meeting describing her frustration with her students’ failure to follow directions and her inability to understand why they would continue to talk despite being told over and over again not to do so. After the role-play was enacted and a few responses generated by the spect-actors, the joker (played by Foram) raised questions to engage Jessica and others in further exploring the assumptions she could be bringing into the interpretation of the situation.

Foram: Jessica, who is a “good” student?

Jessica: Someone who follows directions and someone who does not have to be told things over and over again.

Foram: What were your experiences with talking in your elementary classroom?

Jessica: (Straightening up) Oh, we never talked.

Foram: You never talked. Why did you not talk? Were there rules about talking?

Jessica: I went to a private Catholic school. Our teachers told us once and as students we complied. Our teachers never had to say things over and over again … (Sharing her insight). I guess I am expecting my second graders to be like how we were growing up in a Catholic school environment.

Having awareness about her own cultural frame, Jessica was able to see how this could be impacting her interpretation of student behavior. Jessica reported that she could now see the humanity of her students and was more willing to be tolerant of their “chattering” behavior. She explained that having this awareness helped her to question her expectations and engage in perspective-taking as one possible response to understanding difference.

Based on our experiences of facilitating TO activities within a classroom context, we have come to recognize that the joker plays an important role in supporting the student teachers to reflect critically. We learned that asking explicit questions initiated students to engage in critical conversations regarding their assumptions and cultural frames.

Image Theater

In Image Theater, participants mold their bodies as if they were made of clay, and they may begin to feel the dynamic nature of a world that can be (re)created (Boal 2006). For Boal (2003), in Boalian Theater, images do not remain static. Instead the images are a beginning point and can be transformed to convey further direction or intention. In Image Theater specifically, participants are invited to make still images of their lives, feelings, experiences, and oppressions. Boal (2003) argues that images reflect memories, imagination, emotions, and visions of a future world as we want it to be. For him, images are translations, where the sculptor of the image and the readers of the image “bring things that exist within one context to another context” (Boal 2006, p. 41). In this sense, image is a metaphor as it is a symbolic representation.

In a metaphorical and a visual way, images could specifically help teachers to interpret their work. Lakoff and Johnson (1980) explain that metaphors are symbolic representations and require an understanding and experiencing one kind of thing in terms of another. For example, Johnston (1992) argues that images help teachers put their perspective in a nutshell and cut across different layers of their experiences.

Our purpose for introducing Image Theater was to engage the participating teachers in expressing their deeply held beliefs and perceptions about themselves, their relationships with their students, and their purposes for teaching. We would begin the Image Theater activity with a prompt and then invite the participants to create a frozen image by molding their body as if they were clay, followed by naming their image and reflecting on their individual and the collective images. A few examples of the prompts that we have used are as follows: “Images of your classroom today,” “Images of the issues you have grappled with during teaching,” “Images of your perceived strength as a future teacher,” “Image of a future teacher,” and “Your metaphor as a teacher.” In our work, we have noticed that creating embodied images and reflecting on them thereafter lead to other possibilities of thinking and feeling. These possibilities are rehearsed, and in this way, the process becomes self-repeating.

Occasionally, we have extended the Image Theater activity by adding an arts-based activity right after creating embodied images to deepen the reflective engagement with image work. For this extension activity, we use Play-Doh as a medium for the participants to share and reflect on their symbolic and/or actual representation. The following vignette highlights Kim’s learning about her identity and biases through her participation in Image Theater followed by an arts-based activity using Play-Doh.

Kim’s Vignette: Using the Arts to Reflect on Professional Identity and Biases

Using Image Theater with students as part of their arts-based student teaching seminar, we first invited the participants to create an embodied image of a metaphor that would best describe their teacher identity. After the participants created their embodied image and labeled it, we then invited them to create an arts-based representation using Play-Doh. Creating and reflecting on her metaphor, Kim became aware of how her engagement in the arts-based seminar created insights and tensions that resulted in changes in both her self-perceptions and consequently her professional development. Kim has shared her learnings from this experience at the Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices Conference (Dean and Bhukhanwala 2014).

Kim served as a co-facilitator of the arts-based student teaching seminar, and in the Fall of 2013, she undertook a self-study of her learning through the arts-based approaches about her identity as a developing teacher educator. Foram served as a critical friend for this study, and the data sources included session video, photos, artifacts, session debriefing and planning noted, as well as in-session journaling and written reflections.

As part of our work with student teachers, we engage with the students as a strategy to build shared context as teachers and to model risk-taking for our students. Aligning with a Boalian approach to attending to power dynamics, this strategy of joining with students in the work reflects Schulte’s (2004) perspective that, “By engaging preservice teachers in transformative experiences while simultaneously modeling one’s own transformation process, a teacher educator is providing two experiences to the preservice teacher: how to be transformed and how to transform others” (p. 714). In an activity exploring teacher identity, Kim employed the metaphor “trampoline” as her teaching metaphor. She noted in her reflection that she saw herself as a teacher who accepted students and the energy they brought to learning and then served to ignite passion and enthusiasm in the students such that that energy increased at an exponential rate and the students were thrust to higher levels of engagement, commitment, and learning. This aligned with her long experience as a school-based inclusion facilitator, where she frequently spoke to resistant audiences and honed her skills in “selling” and “igniting.” The trampoline metaphor captured Kim’s perceived strengths (spontaneity and responsiveness) and resonated with the positive aspects of evaluations she received in her teaching. The following semester, Kim chose to develop a new metaphor based on departmental restructuring of the school of education which resulted in the need to formalize many informal structures and develop new roles and protocols. This led to significant role diffusion and a feeling of chaos that caused some anxiety for Kim, and she felt that she needed to be more organized and structured to cope with the demands this shift placed on her. The trampoline metaphor felt too uncontrolled and lacking the structure she felt was demanded of her approaches to practice in her work.

A second impetus for revisiting her metaphor was her developing insight about her expectations of passivity in students. Kim reflected that in the context of the arts-based seminar, she often was struck by the powerful insights the students shared. Some of these students had previously been in courses that Kim had taught, but she had perceived these students as somewhat disengaged. This was based on their reserved participation in discussion. Her first instinct was to identify these students as different from her in their more quiet nature in the classroom. She reflected that she was privileging verbal engagement and the social skill of mirroring her enthusiasm. Further reflection revealed that several of the students who most “surprised her” were African-American. Participating with students in Theater of the Oppressed and arts-based activities helped her to see these students in a different light and understand that her expectations for depth were based on the students’ communication style and thus, for many students, were mistakenly low. Many of the activities we facilitated created opportunities for the students to reflect and engage deeply in a context where permission for risk-taking was explicit and participation was highly contextualized to individualized, student-centered funds of knowledge. Tidwell (2002) notes the challenge of teacher educators is to value the students’ ways of knowing and ways of negotiating their learning, an understanding which Kim found through reflection as well.

Insight into her faulty expectations of passivity in students as well as her flawed beliefs that her energy and passion were a key impetus for student engagement rather than the students’ deep connection to their experiences and construction of content knowledge lead her to explore a new metaphor. This new metaphor could help her to reimagine her interactions as a teacher educator outside the arts-based seminar and in her teacher education classroom. She devised a metaphor to help her support students in taking more ownership in their learning. Kim changed her metaphor of teacher as a “trampoline” to teacher as a “ladder.” For Kim, “ladder” represented more linearity, structure, and focus as opposed to the diffuse energy of the trampoline. This metaphor reflected the value Kim newly placed on the students’ agency in climbing, reaching, and claiming their learning. However, Kim felt that this metaphor was “forced.”

Later in the semester, participants were invited to transform their metaphors by altering or recreating their artifact. At this point, Kim chose to construct a blended metaphor that pulled together the inherent strengths present in the “trampoline” metaphor and the “ladder” metaphor. She named her combined new metaphor as “scaffolded trampoline.” She noted that she saw this configuration as an addition of structure to the model of enthusiasm and passion instead of a replacement. This allowed room for Kim to value the passion and enthusiasm she modeled for students while consciously creating space for students’ ownership of their learning and explicit reminders to create space, classroom climate, and explicit expectations beyond traditional classroom discussion and writing assignments for all students to make visible their passion and transformation.

Thus, through the embodied processes of creating images and/or arts-based representations, Kim examined her beliefs, biases, and ways of being within her practice. The TO activities allowed her to see her students in a new light and then engage in an activity asking her to transform her vision of herself as a teacher served as a tool for powerful and uncomfortable insight. Kim became more self-aware, and in turn her practice became more focused on empowering student voice and power in the learning process. This shift reflects the outcomes Schulte (2004) cites when teacher educators engage in critical reflection of their practice:

The transformation of teachers can also lead to more democratic classrooms where teachers recognize the power dynamics in educational processes and society. When teachers make these power dynamics explicit to their students, they also put up for examination the teacher’s power within the classroom. The primary goal is that through better understanding themselves and their positions within their classroom, teachers will begin to better understand their students, especially those who are different from them. (p. 712)

Enacting arts-based explorations allowed her to imagine new possibilities and new ways to reimagine her practice as a more aware and socially just teacher educator.

Part 3: Addressing Challenges in Using Theater of the Oppressed Toward a Socially Just Teacher Education Program

In their work, Placier et al. (2008) identified both the value of using TO within social justice teacher education and the potential challenges they experienced. Challenges such as student resistance to TO activities and their resistance to the notion of “oppression” were two of the biggest obstacles they encountered. We agree that resistance creates a block to the experience itself which may then impact the learning from the experience. Similarly, Forgasz and McDonough (2017) have identified willingness to be vulnerable and unfamiliarity to the pedagogy as posing two additional challenges when working with embodied pedagogies such as TO. Lawrence (2012) argues that “promoting embodied pedagogies often means breaking through boundaries and challenging dominant ideologies and epistemologies that tell us our minds are the primary sources of learning” (p. 76). We have noticed this as being true in our experiences of working with TO activities as well.

Grounded in our learnings from using TO within teacher education (Bhukhanwala et al. 2016), we argue that a teacher educator who wishes to use TO in his/her classroom should first seek some form of experiential training both as a participant and as a facilitator. The activities should be used intentionally, and an effort should be made to create a conducive learning environment. We have identified the following characteristics that could support the students in participating in embodied activities such as TO and in examining their frames of reference and eventually imagining ways to transform them.

A Shared Ordeal

The seminar brought together groups who were experiencing similar dilemmas at a given time. This shared understanding allowed peers to empathize with, support, as well as learn from one another. We believe that this was an important characteristic, because when student teachers perceived that someone else’s dilemma was similar to their own or they were also likely to experience this dilemma in the future, the student teachers took ownership in the learning (Bhukhanwala et al. 2016). They took a stance of a learner, rather than the stance of an “expert.” From the stance of a learner, the student teachers were more likely to put themselves in the situation, examine their frames of reference, generate possibilities for themselves, and learn those generated by others. In this sense, student teachers worked in a safe space to rehearse for reality.

On the other hand, when the student teachers took the stance of an “expert,” they were more likely to exclude themselves from the situation and suggest what someone else could do to fix the situation. From our perspective, Boalian Theater is more about rehearsing possibilities and engaging in collective problem-solving, rather than “telling” or “fixing.” Thus, having a shared ordeal allowed for student teachers to take ownership and take the stance of a learner, which in turn supported the work.

Starting with a Participant Dilemma

Student teachers can take ownership of their learning process when the disorienting dilemmas explored in the seminar meetings come directly from their lived experiences. In these instances, student teachers are more likely to see the relevance of their participation to their life outside the seminar meeting and are further motivated to work through the dilemmas, imagine possibilities, and take action.

Creating a Safe Space

It is important for participants to feel safe when engaging in this work since, for many, working with an embodied pedagogy itself is a relatively new experience and often puts them outside of their comfort zone (Bhukhanwala et al. 2016). Therefore, it is important for facilitators to take intentional steps to create a safe space. We did this by creating group norms with the participants early in the semester. Some examples of the norms the groups set include keeping confidentiality, being respectful, listening rather than passing judgment, stepping up, and making the experience new. We (the facilitators) often added an additional norm that involved being playful and playing within the parameters of one’s own body. Our purpose in adding this last norm was to help the participants recognize that they had a choice in deciding how they wanted to participate and how much they wanted to share.

Being Vulnerable and Learning from Experiences

All participants and facilitators engaged in the activities and took turns taking risks and being vulnerable. As facilitators, we made this nature of the work explicit to the participants and modeled it for them through our participation as well as by listening, supporting, and scaffolding the participants in their moments of vulnerability. For example, in arts-based activities like Play-Doh and pipe cleaners, we (the facilitators) too shared and examined dilemmas we experienced as teachers in our university classrooms. Like the student teachers, we used the aesthetic space to examine our frames of reference, engage in imagining possibilities, and connect and empathize with our students.

Empathetic Peer Involvement

The activities often involved working and collaborating with peers. We have noticed that the group benefits most when participants come into this work from a frame of reference that is more situated in empathy and learning, rather than in advice-giving. For peers to empathize, they need to recognize the connections between their experiences and the dilemma being presented and then engage in generating solutions as ways of creating possibilities, not only for others but also for themselves (Bhukhanwala et al. 2016). We encouraged and reminded participants to ask themselves, “How is this true for me?” when exploring peers’ dilemmas.

Role of the Facilitator

Facilitators play a variety of critical roles in optimizing the value of the TO activities. These include creating a safe environment, listening to disorienting dilemmas, selecting Boalian and other arts-based activities that could best support the examination of a dilemma, engaging the participants in an embodied critical reflection and a discourse, inviting participants to imagine possibilities, and guiding them toward newer frames of reference that could enable the student teachers to have agency to transform an oppressive or a divisive experience to one that felt more inclusive, democratic, and humane.

Implications for Self-Study and Self-Study Research

Through self-study research, we have come to understand that teachers today are posed with new challenges. Many teachers perceive teaching to be a complex experience as something to “survive,” as opposed to a time of profound growth and transformation. The emerging tensions are often held within one’s body, making teaching a complicated, emotional, interpersonal, and embodied experience. By examining the participants’ experiences and their discomforting emotions and critically reflecting on our own experiences and emotions as facilitators/participants, we have come to see that TO activities offer rich opportunities for learning within a teacher education program seeking to be socially just.

Furthermore, in using Mezirow’s (1997) framework for creating transformative learning experiences, we found that arts-based approaches can offer a space for transformative learning. Through embodied theatrical dialogue, these participants (a) made visible their dilemma and discomforting emotions; (b) reflected on their beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and assumptions; (c) engaged in perspective-taking; and (d) used imagination to redefine the dilemma and/or rehearse possible alternative actions. Through embodied engagement, teachers identified new ways of engaging, negotiating, and using their voice and agency to change a divisive and power-driven relationship to a more open, inclusive, democratic, and humane one.

The challenges that we experienced when studying TO as a teacher education practice are as follows: (a) our seminars required voluntary participation, while all students were required to attend a mandatory seminar each week throughout their student teaching seminar. This slightly impacted the duration, frequency, and participation of the students in the TO-based seminars; (b) during analysis, we drew much of our data from photographs and videos of each seminar meeting. These methods allowed us to generate rich and robust data. However, we also learned that viewing hours of video data was time-consuming and pushed us to become more systematic and disciplined in our work; (c) while critically reflecting on our practice and our assumptions and biases, we found that we had to stay open to what we found. Sometimes this became a partial challenge, and working with a trusted critical friend allowed us as researchers to be both human and at the same time willing to look at our assumptions in new ways; and (d) we experienced moments of tension when our insights from the work revealed less than ideal aspects of our program, and we took the learnings from our larger research study to make programmatic changes that went beyond our own classrooms.

To further this work, we invite teacher educators to engage in collaborative self-study and experiment with TO activities. Collaborative self-study creates safe spaces for teacher educators to experiment, to be tentative, to be vulnerable as well as to challenge each other’s taken-for-granted assumptions, support learning, and provide feedback. In addition, we encourage them to share their learning about using TO activities in socially just teacher education programs as a way to continue the dialogue and to further deepen our collective knowledge and craft.

References

Apple, M. (2000). Official knowledge: Democratic education in a conservative age. New York: Routledge.

Bakhtin, M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays (trans: Emerson, C., & Holquist, M.). Austin: University of Texas Press.

Bhukhanwala, F. (2007). Pre-service teachers’ perspectives on pedagogy and theater of the oppressed: Outcomes and potential (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Athens: University of Georgia.

Bhukhanwala, F. (2012). Learning from using theater of the oppressed in a student teaching seminar: A self-study. In S. Pinnegar (Ed.), Extending inquiry communities: Illuminating teacher education through self-study. Proceedings of the ninth international conference on self-study of teacher education practices (pp. 52–55). [Herstmonceux Castle, UK]). Kingston: Queen’s University.

Bhukhanwala, F., & Allexsaht-Snider, M. (2012). Diverse student teachers making sense of difference through engaging in Boalian theater approaches. Teaching and Teacher Education: Theory and Practice, 18(6), 675–691.

Bhukhanwala, F., Dean, K., & Troyer, M. (2016). Beyond the student teaching seminar: Examining transformative learning through arts-based approaches. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 23(5), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1219712.

Blanco, J. (2000). Theater of the oppressed and health education with farm workers: A primary research project. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Tallahassee: Florida State University.

Bloomfield, D. (2010). Emotions and ‘getting by’: A pre-service teacher navigating professional experience. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3), 221–234.

Boal, A. (1979). Theater of the oppressed. (trans: McBride, C., & McBride, M.). New York: Urizen.

Boal, A. (2003). Games for actors and non-actors. New York: Routledge.

Boal, A. (2006). The aesthetics of the oppressed. New York: Routledge.

Britzman, D. (2003). Practice makes practice: A critical study of learning to teach. Albany: SUNY.

Britzman, D. P. (2007). Teacher education as uneven development: Toward a psychology of uncertainty. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 10(1), 1–12.

Brown, E. (2004). The significance of race and social class for self-study and the professional knowledge base of teacher education. In J. Loughran, M. Hamilton, V. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (Vol. 1, pp. 517–574). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Burgoyne, S., Welch, S., Cockrell, K., Neville, H., Placier, P., Davidson, M., & Fisher, B. (2005). Researching theater of the oppressed: A scholarship of teaching and learning project. Mountain Rise, 2(1). Retrieved from http://www.wcu.edu/facctr/mountainrise/archive/vol2no1/html/researching_theatre.html.

Burgoyne, S., Placier, P., Thomas, M., Welch, S., Ruffin, C., Flores, L. Y., & Miller, M. (2007). Improvisational theatre and self-efficacy. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 111, 21–26.

Butterwick, S., & Lawrence, R. L. (2009). Creating alternative realities: Arts-based approaches to transformative learning. In J. Mezirow & E. Taylor (Eds.), Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education (pp. 35–45). Hoboken: Wiley.

Cahnmann-Taylor, M., & Souto-Manning, M. (2010). Teachers act up: Creating multicultural learning communities through theater. New York: Teachers College Press.

Clark, C. M. (2001). Good conversation. In C. M. Clark (Ed.), Talking shop: Authentic conversation and teacher learning (pp. 172–182). New York: Teachers College Press.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2004). Practitioner inquiry, knowledge, and university culture. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. K. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (Vol. 1, pp. 817–869). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Cockrell, K., Placier, P., Burgoyne, S., Welch, S., & Cockrell, D. (2002). Theater of the oppressed as a self-study process: Understanding ourselves as actors in teacher education classrooms. In C. Kosnik, A. Freese, & A. Samaras (Eds.), Making a difference in teacher education through self-study. Proceedings for the fourth international conference on the self-study of teacher education practices (pp. 43–47). Toronto: OISE, University of Toronto.

Cole, A., & Knowles, G. (2008). Arts-informed research. In G. J. Knowles & A. L. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples and issues (pp. 55–70). Los Angeles: Sages Publications.

Cranton, P., & Taylor, E. (2012). Transformative learning theory: Seeking a more unified theory. In E. Taylor & P. Cranton (Eds.), The handbook of transformative learning: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 3–20). San Francisco: Wiley.

Dean, K., & Bhukhanwala, F. (2014). Moving through the triangle: Self-study of the impact of engaging in theater of the oppressed with student teachers on the practice of teacher educator. In D. Garbett & A. Ovens (Eds.), Changing practices for changing times: Past, present and future possibilities for self-study research. Proceedings of the tenth international conference on self-study of teacher education practices (pp. 53–63). Kingston: Queen’s University.

Dirkx, J. (2001). The power of feelings: Emotion, imagination, and the construction of meaning in adult learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 89, 63–72.

Eisner, E. (2008). Persistent tensions in arts-based research. In M. Cahnmann-Taylor & R. Siegesmund (Eds.), Arts-based research in education: Foundations for practice (pp. 16–27). New York: Routledge.

Estola, E., & Elbaz-Luwisch, F. (2003). Teaching bodies at work. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 35(6), 697–719.

Forgasz, R. (2014). Bringing the physical into self-study research. In A. Ovens & T. Fletcher (Eds.), Self-study in physical education teacher education: Exploring the interplay of practice and scholarship (pp. 15–28). London: Springer.

Forgasz, R., & Berry, A. (2012). Exploring the potential of Boal’s “the rainbow of desire” as an enacted reflective practice: An emerging self-study. In S. Pinnegar (Ed.), Extending inquiry communities: Illuminating teacher education through self-study. Proceedings of the ninth international conference on self-study of teacher education practices (pp. 106–109). Kingston: Queen’s University.

Forgasz, R., & McDonough, S. (2017). “Struck by the way our bodies conveyed so much:” A collaborative self-study of our developing understanding of embodied pedagogies. Studying Teacher Education, 13(1), 52–67.

Forgasz, R., McDonough, S., & Berry, A. (2014). Embodied approaches to S-STEP research into teacher educator emotion. In Changing practices for changing times: Past, present and future possibilities for self-study research, proceedings of the tenth international conference on self-study of teacher education practices (pp. 82–84). Kingston: Queen’s University.

Foucault, M. (1984). The subject and power. In B. Wallis (Ed.), Art after postmodernism (pp. 417–432). Boston: Godine Publishers.

Freire, P. (1970). The pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Freire, P. (2004). Pedagogy of indignation. Boulder: Paradigm.

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social learning. New York: Teachers College Press.

Griffiths, M., Bassa, L., Johnston, M., & Perselli, V. (2004). Knowledge, social justice and self-study. In J. Loughran, M. Hamilton, V. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (Vol. 1, pp. 651–707). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Hamilton, M., & Pinnegar, S. (2015). Considering the role of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices research in transforming urban classrooms. Studying Teacher Education, 11(2), 180–190.

Harman, R., & French, K. (2004). Critical performative pedagogy: A feasible praxis in teacher education? In J. O’Donnell, M. Pruyn, & R. Chavez (Eds.), Social justice in these times (pp. 97–116). Greenwich: New Information Press.

Hinchion, C. & Hall, K. (2016). The uncertainty and fragility of learning to teach: A Britzmanian lens on a student teacher story. Cambridge Journal of Education, 46 (4), 417–433.

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge.

Johnston, S. (1992). Images: A way of understanding the practical knowledge of student teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 8(2), 123–136.

Jordi, R. (2011). Reframing the concept of reflection: Consciousness, experiential learning, and reflective learning practices. Adult Education Quarterly, 61(2), 181–197.

Kitchen, J., Ciuffetelli Parker, D., & Gallagher, T. (2008). Authentic conversation as faculty development: Establishing a self-study group in an education college. Studying Teacher Education, 4(2), 157–177.

Kitchen, J., Fitzgerald, L., & Tidwell, D. (2016). Self-study and diversity: Looking back, looking forward. In J. Kitchen, L. Fitzgerald, & D. Tidwell (Eds.), Self-study and diversity II: Inclusive teacher education for a diverse world (pp. 1–10). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Kroth, M., & Cranton, P. (2014). Stories of transformative learning. Boston: Sense Publishers.

LaBoskey, V. (2004). Afterword moving the methodology of self-study research and practice forward: Challenges and opportunities. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. K. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (Vol. 1, pp. 1169–1184). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

LaBoskey, V. (2009). “Name it and claim it”: The methodology of self-study as social justice teacher education. In Research methods for the self-study of practice (pp. 73–82). Dordrecht: Springer.

LaBoskey, V. (2015). Self-study for and by novice elementary classroom teachers with social justice aims and the implications for teacher education. Studying Teacher Education, 11(2), 97–102.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Lawrence, R. (2012). Coming full circle: Reclaiming the body. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 134, 71–78.

Linds, W. (2006). Metaxis: Dancing (in) the in-between. In J. Cohen-Cruz & M. Schutzman (Eds.), A Boal companion: Dialogues on theater and cultural politics (pp. 114–124). New York: Routledge.

Loughran, J. (2002). Understanding self-study of teacher education practices. In J. Loughran & T. Russell (Eds.), Improving teacher education practices through self-study (pp. 239–248). New York: Routledge.

McDonough, S., Forgasz, R., Berry, M., & Taylor, M. (2016). All brain and still no body: Moving towards a pedagogy of embodiment in teacher education. In D. Garbett & A. Ovens (Eds.), Enacting self-study as methodology for professional inquiry (pp. 433–440). Herstmonceux: S-STEP.

Merriam, S., & Kim, S. (2012). Studying transformative learning: What methodology? In E. Taylor & P. Cranton (Eds.), Handbook of transformative learning: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 56–72). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Merryfield, M. (2000). Why aren’t teachers being prepared to teach for diversity, equity, and global interconnectedness? A study of lived experiences in the making of multicultural and global education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16, 429–443.

Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 74, 5–12.

Mezirow, J. (1998). On critical reflection. Adult Education Quarterly, 48(3), 185–198.

Mezirow, J., & Taylor, E. (Eds.). (2011). Transformative learning in practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mitchell, C., O’Reilly-Scanlon, K., & Weber, S. (Eds.). (2013). Just who do we think we are?: Methodologies for autobiography and self-study in education. New York: Routledge.

Nias, J. (1996). Thinking about feeling: The emotions in teaching. Cambridge Journal of Education, 26(3), 293–306.

Nieto, S. (2004). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education. New York: Pearson.

Olsen, B. (2010). Teaching for success: Developing your teacher identity in today’s classroom. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers.

Osterlind, E. (2011). Acting out of habits – Can theatre of the oppressed promote change? Boal’s theatre methods in relation to Bourdieu’s concept of habitus. Research in Drama Education, 13(1), 71–82.

Pagis, M. (2009). Embodied self-reflexivity. Social Psychology Quarterly, 72(3), 265–283.

Pinnegar, S., & Hamilton, M. L. (2009). Self-study of practice as a genre of qualitative research: Theory, methodology, and practice (Vol. 8). Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media.

Placier, P., Burgoyne, S., Cockrell, K., Welch, S., & Neville, H. (2005a). Learning to teach with theatre of the oppressed. In J. Brophy & S. Pinnegar (Eds.), Learning from research on teaching (pp. 253–280). Oxford: Elsevier.

Placier, P., Cockrell, K., Cockrell, D., & Simmons, J. (2005b). Acting upon our beliefs: Using theatre of the oppressed in our teacher education practice. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Education Research Association, Montreal.

Placier, P., Cockrell, K., Burgoyne, S., Welch, S., Neville, H., & Eferakorho, J. (2008). Theater of the oppressed as an instructional practice. In C. Kosnik, C. Beck, A. Freese, & A. Samaras (Eds.), Making a difference in teacher education through self-study. Studies of personal, professional, and program renewal (pp. 131–146). Dordrecht: Springer.

Popen, S. (2006). Aesthetic spaces/imaginative geographies. In J. Cohen-Cruz & M. Schutzman (Eds.), A Boal companion: Dialogues on theater and cultural politics (pp. 114–124). New York: Routledge.

Prentki, T., & Selman, J. (2000). Popular theater in political culture: Britain and Canada in focus. Bristol: Intellect.

Samaras, A. P. (2009). Explorations in using arts-based self-study methods. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 23(6), 719–736.

Samaras, A. P. (2010). Self-study teacher research: Improving your practice through collaborative inquiry. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Satina, B., & Hultgren, F. (2001). The absent body of girls made visible: Embodiment as the focus in education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 20(6), 521–534.

Schulte, A. K. (2004). Examples of practice: Professional knowledge and self-study in multicultural teacher education. In J. Loughran, M. Hamilton, V. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 709–742). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Schutzman, M. (2006). Joker runs wild. In J. Cohen-Cruz & M. Schutzman (Eds.), A Boal companion: Dialogues on theater and cultural politics (pp. 133–145). New York: Routledge.

Souto-Manning, M. (2011). Playing with power and privilege: Theatre games in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 27, 997–1007.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Sutton, R. (2005). Teachers emotions and classroom effectiveness. The Clearing House, 78(5), 229–234.

Tidwell, D. (2002). A balancing act. In J. Loughran & T. Russell (Eds.), Improving teacher education practices through self-study (pp. 30–42). New York: Routledge.

Tidwell, D., & Fitzgerald, L. (Eds.). (2006). Self-study and diversity (Vol. 2). Boston: Sense Publishers.

Weber, S., & Mitchell, C. (2004). Visual artistic modes of representation for self-study. In J. Loughran, M. Hamilton, V. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 979–1037). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Zeichner, K. (2007). Accumulating knowledge across self-studies in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(1), 36–46.

Zembylas, M. (2005). Beyond teacher cognition and teacher beliefs: The value of the ethnography of emotions in teaching. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 18(4), 465–487.

Zembylas, M., & Chubbuck, S. (2012). Growing immigration and multiculturalism in Europe: Teachers’ emotions and the prospects of social justice education. In C. Day (Ed.), The Routledge international handbook of teacher and school development (pp. 139–148). New York: Routledge.

Zembylas, M. & McGlynn, C. (2012). Discomforting pedagogies: Emotional tensions, ethical dilemmas and transformative possibilities. British Educational Research Journal, 38(1), 41–59.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Section Editor information

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry

Bhukhanwala, F., Dean, K. (2020). Theater of the Oppressed for Social Justice Teacher Education. In: Kitchen, J., et al. International Handbook of Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6880-6_24

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6880-6_24

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-6879-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-6880-6

eBook Packages: EducationReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Education